Abstract

Low radiation is one of the most important factors which limits potential yield in potato. Under humid conditions, the dominance of diffuse radiation not only imposes challenges for radiation use efficiency in crops but also limits the water status surveillance through non-invasive methods like infrared radiometry. This study was carried out in the humid desert of the Peruvian central coast with the aim to relate maximum stomatal conductance (gs_max, an important water status indicator) with leaf and air temperature (dT) and crop water stress index (CWSI). In a potted trial, gs_max vs. dT were compared along the day in well-irrigated (field capacity) and water restricted (half field capacity) plants. In an additional field experiment, CWSI was validated by testing two irrigation timing treatments with pre-established gs_max threshold (0.15 [T1] and 0.50 [T2] mol H2O m−2 s−1) against a control (frequently irrigated). An acute stomatal closure sensitivity was detected which drove a gs_max fall (gs↓) near the solar noon. The intense stomatal closure caused a dT rise which showed positive higher values (> 2 °C) after gs↓. The significant yield reduction of T1 in relation to the control (− 38.2 ± 10.7%) highlighted that gs_max values > 0.15 must be used to warrant a high potato yield. These findings support the use of CWSI values ≤ 0.3–0.4 as thresholds for an appropriate irrigation in potatoes with assessments taken at around 15:00 hours, time in which plants have accumulated enough radiation allowing an appropriate detection of thermal emission under humid conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potato is one of the most important crops and widely grown in the world (Harris 1992), considered as the third edible crop in production after wheat and rice (FAO 2018). This crop is regarded as sensitive to water deficit, due to its shallow root system (Ahmadi et al. 2010), requiring accurate determination of water status needed to optimize water management and maximize yield (Ierna and Mauromicale 2006; Monneveux et al. 2013; Ramírez et al. 2016a, b). Most global potato cultivation systems are rain-fed, where humid conditions are dominant (Vos and Oyarzún 1987; Vos and Groenwold 1989; Haverkort and Struik 2015). Radiation reduction, throughout the rainy season, is considered as a critical factor to achieve potato yield potential (Haverkort and Struik 2015). Despite the important radiation use efficiency increment reported for this crop under humid environments (Quiroz et al. 2017), there is a need to assess how the potato water status behaves under conditions where diffuse radiation dominates.

In general, plant water status can be defined in terms of plant water potential and water content (Kramer 1988). It has been well established that reduction in water contents dramatically reduce crop yield (Kramer 1983; Steduto et al. 2012), including potatoes (van Loon 1981; Harris 1992; Foti et al. 1995; Ierna and Mauromicale 2006). In this regard, some authors (Medrano et al. 2002; Flexas et al. 2004; Flexas et al. 2006) proposed the use of mid-morning or maximum, light-saturated stomatal conductance (gs_max) as an objective way to establish water status in plants using a standardized parameter based on a physiological threshold that leads to photosynthetic impairment, if surpassed. Thus, photosynthesis performs satisfactorily at gs_max values higher than 0.10–0.15 mol H2O m−2 s−1 which are targeted as irrigation threshold in crops (Flexas et al. 2006). Medrano et al. (2002) highlighted the importance to prevent plants from falling below 0.05 mol H2O m−2 s−1 (recognized as a severity threshold in potato; Ramírez et al. 2016a) because irreversible physiological impairment may occur. On the other hand, because stomatal closure increases foliage temperature, due to the reduction in dissipation power (Jackson et al. 1981; Jones 1999), this variable is also recognized as a good indicator of crop water status (Idso et al. 1981; Jackson et al. 1981; Jones 2004b; Möller et al. 2007; Prashar et al. 2013).

Notwithstanding, plant water status assessment for irrigation purposes has been criticized because they entail invasive and laborious measurements taken at leaf scales (Jones 2004b). Evidently, assessing water status of a few leaves would seldom represent the water status of the field, and thus irrigation decisions would benefit from non-invasive and non-destructive methods covering larger extents. Remotely sensed methods are currently under evaluation as tools for assessing plant water status at different scales, providing near real-time assessments. Thus, the detection of thermal radiation emitted by foliage surface—via radiometric temperature estimated by thermometry or infrared thermography—provides a portable, non-destructive and non-invasive method for estimating foliar temperatures (Jones 2004a). These techniques have been widely used for the definition of water stress indexes in different crops (Idso et al. 1981; Jones 1999; Möller et al. 2007; Meron et al. 2010) including potato (Stark and Wright 1985; Stark et al. 1991; Prashar et al. 2013; Rud et al. 2014; Ramírez et al. 2016a). The crop water stress index (CWSI) is one of the radiometric temperature-based indices developed for arid climates (Jones 1999, 2004a). In potato, Ramírez et al. (2016a) suggested CWSI values < 0.4 for an appropriate irrigation threshold in clear and dry environments. However, CWSI is less reliable under humid conditions (Jones 1999) such as the foggy Peruvian Desert Coast, characterized by high atmospheric humidity (Beresford-Jones et al. 2015). These climatically challenging areas require a fine-tuning of the thresholds to be useful for farmers. To ascertain the feasibility of using foliage radiometric temperature as an indicator of the water status in potato under a cloudy-humid environment, experiments under controlled and field conditions were carried out in the Peruvian Central Coast with the aim to define the most appropriate time during the day in which infrared thermometry reflects water status in potato and to analyze CWSI values for an optimum tuber yield in this kind of environment.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Stomatal Conductance Assessment

The potato cultivar used was UNICA (CIP code: 392797.22), a genotype screened in the Peruvian Coast and characterized by its tolerance to heat and virus attack (Gutiérrez-Rosales et al. 2007). This cultivar has also shown a moderate tolerance to water restriction (Cabello et al. 2012; Ramírez et al. 2015; Rolando et al. 2015). The water status was measured in the apical leaflet of the third upper leaf from the top, through maximum stomatal conductance at saturated light (gs_max). Using a photosynthesis portable system (LI-6400TX, LI-COR, Nebraska, USA), the in situ photosynthetic active radiation saturation point for this cultivar was estimated at 1500 μmol m−2 s−1. The other micro-meteorological variables fixed in the chamber were 400 ppm of CO2, 9.29 mol m−2 s−1 of boundary layer conductance and 1.0–1.9 kPa of vapour pressure deficit (VPD).

First Experiment—Leaf Temperature and g s_max along the Day Under Different Water Conditions

A potted experiment was carried out at the International Potato Center (CIP) experimental station in Lima, Peru (12.08° S, 76.95° W and 244 m above sea level). On April 8, 2016, 20 seeds were sown in plastic pots (6.4 L) and supplied with 6.5 kg of a mixture (2:1) composed by sand and SOGEMIX organic substrate (PRO-MIX, Premier Tech Horticulture, Canada), adding 500 g at hilling, 21 days after planting (DAP). Each pot was fertilized with 300 g, 45 mL and 96 g of NH4·NO3 (31% N), H3PO3 (53% P2O5) and KNO3 (13% of N and 46% K2O), respectively, distributed in 11 weekly applications. Pest control was carried out by spraying 5 mL L−1 of a vegetal oil (AGRO OIL-EC Garden, Agrocol S.A., Colombia) every 12 days. The pots were watered to saturation until May 19 (approximately at tuber initiation onset), the moment at which two water status treatments were established (10 pots per treatment):

-

1.

Control: pots were irrigated until field capacity (0.32 v/v).

-

2.

Mild water restriction: pots were irrigated until 50% of field capacity. The pots were watered three times per week, where soil water contents were measured gravimetrically—using Rolando et al.’s (2015) protocol for every pot—to quantify irrigation water.

Four gs_max assessments were conducted (May 6, 20 and June 2, 9, 2016) every 2 h during 07:00 to 18:00 hours local time for each plant (gs_max measurements for all the plants took 1 h approximately). In the same leaflet and immediately after gs_max measurement, radiometric temperature was taken at 0.1 m of distance using an infrared thermometer (DT-882 model, CEM, China) with an optical resolution of 8 (distance):1 (spot size). The fixed emissivity value was 0.95. The difference between leaf and air temperatures (dT) was calculated using the information from the infrared thermometer and an atmospheric thermometer installed in a micrometeorology station (HOBO U12 Outdoor/Industrial Data Logger, Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, USA) located at approximately 1 m from the group of assessed plants. The harvest was carried out on July 5, 2016, when all the tubers were weighted and dried at 80 °C for 3 days to obtain dry tuber biomass. Throughout the study, average daily temperature, atmospheric humidity and global radiation (measured by the micrometeorology station) were 19.3 ± 0.24 °C, 83.2 ± 0.58% and 12.9 ± 0.54 MJ m−2 day−1, respectively.

Second Experiment—Crop Water Stress Index and its Relationship with Water Status Proxies

Field Characteristics

A field trial was established at CIP experimental station in Lima, Peru, during October 3, 2016–January 16, 2017. The study site was characterized by a sandy loam soil texture (54, 29 and 17% of sand, silt and clay, respectively), with an average organic matter content, gravimetric field capacity, bulk density, pH and electrical conductivity of 8%, 0.18 w/w, 1.5 g cm−3, 7.5 and 2.8 dS m−1, respectively. During the study period, the average maximum and minimum daily temperature were 24.8 ± 0.3 °C and 17.4 ± 0.2 °C, respectively, and atmospheric humidity ranged between 91.0 ± 0.3 and 57.5 ± 0.7% (atmospheric temperature and humidity sensor HC2S3 model, Campbell, USA) (Table 1). The daily average global radiation (LI200X model, Licor, USA) and VPD during the experiment were 17.7 ± 0.4 MJ m−2 day−1 and 0.6 ± 0.02 kPa, respectively (Table 1).

Crop Management and Experimental Design

Using a randomized complete block design (RCBD), the experiment was conducted in a 416 m2 total area, divided in 12 plots (3.6 × 5 m2 each) duly allocated in 4 blocks (three plots per block). Sixty plants per plot were sown in five rows with a plant and furrow distance of 0.3 and 1 m, respectively. The fertilization consisted in a dose of 180:120:160 kg ha−1 of N/P2O5/K2O using NH4NO3, (NH4)2HPO4 and K2SO4 fertilizers applied at planting and during hilling, which occurred at 30 DAP. Pest and disease control were incorporated into an integrated pest management program which involved the rotation of products with different mechanisms of action. Thus, Movento (Bayer AG, Monheim am Rhein, Germany), Vertimec (Syngenta Crop Protection AG, Basilea, Switzerland) and Evisetc-S (Arysta Life Science, USA) were weekly rotated from 15 to 45 DAP using doses of 0.5 L ha−1, 0.5 L ha−1 and 600 g ha−1, respectively. Seven furrow irrigations were provided at 0, 4, 7, 11, 17, 22 and 30 DAP watering every plot with approximately 67 mm per irrigation; after that, a drip irrigation system was set up independently for each plot, locating two drip tapes per row 0.35 m away from the plants. The spacing between emitter, emitters flow rate and pressure were 0.2 m, 1.3 L h−1 and 0.5 MPa, respectively, and the pressured water was supplied by a motor pump (1 hp, Venus 33M, ESPA, Spain) connected to a tank with 5000 L capacity. Three irrigation treatments, with different irrigation timings, were randomly assigned for every plot within each block. Thus, a control treatment was irrigated based on soil matric potential readings keeping the soil below 35 kPa. For this purpose, three tensiometers (model R, Irrometer Company Inc., Riverside, CA, USA) per control plots were randomly located and buried to 0.3-m soil depth. The irrigation timing for the other two treatments were based on gs_max threshold values: 0.15 (T1) and 0.05 (T2) mol H2O m−2 s−1. To accomplish this, frequent gs_max estimations (three to four times per week) were conducted in T1 and T2 plots to make sure average gs_max was maintained below the target threshold. Thus, four central plants/plot were monitored between 07:00 and 10:00 hours, following the aforementioned procedure (see “Plant Material and stomatal conductance assessmentS12” section). Once the irrigation moment for any plot was determined, irrigation times were defined, based on volumetric soil water calculation through four random soil samples per plot (sampled at 0.3-m soil depth). Details of the protocols were provided by Ramírez et al. (2016a), considering 1.5 g cm−3, 0.35 m and 0.3 m of soil bulk density, root-zone width and depth, respectively.

Response Variables

In all the plots, seven gs_max evaluations were conducted (9th, 15th, 23th and 29th of November and 6th, 13th and 20th of December 2016) in four plants located in the centre of each plot from 07:00 to 11:00 hours (see details in “Plant Material and stomatal conductance assessment” section). Immediately after, thermal images of the four target plants and a wet artificial reference surface (details in Ramírez et al. 2016a) were taken from 13:00 to 15:00 hours at 3-m distance. An infrared thermal camera (E60 Model, FLIR Systems Inc., Sweden)—lens with angular field of view of 25° and a resolution of 320 × 240 pixels and sensitive in the 7.5–13 μm spectral range—was used. Thermal emissivity was set to 0.96, and reflected apparent temperature was calculated every six images using the direct method (FLIR 2016). With visible RGB images (3.1 Mpixels) taken by the infrared camera simultaneously with thermal images—and following Ramírez et al. (2016a) procedure for aligning thermal-visible images—we estimated the canopy temperature of the target plants. Crop water stress index (CWSI) was estimated following the empirical method used in potato (Ramírez et al. 2016a):

where Tcanopy is the measured crop canopy temperature, Twet is the wet artificial reference surface measured temperature and Tdry is 13 °C over the dry bulb temperature. On January 16, 2017, all plants—excluding those located in the borders—were harvested and all tubers weighted. Tubers belonging to six central plants were dried at 60 °C until constant weight to estimate dry tuber biomass (DTB). A composite sample of dry tubers from four plants was ground using a ball mill (BMIX-100 model, MRC, Holon Israel) and 2.8–3.7 mg of tuber dry biomass packed in tin capsules and sent to the Stable Isotope Facility of the University of California-Davis for 13C analyses. A carbon isotope discrimination (Δtuber) calculation was done following Ramírez et al. (2015) procedure.

Statistical Analyses

In the potted trial, the effects of water status treatments, time and their interaction on gs_max and dT were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA for each assessment date. The analyses were followed by a Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test to determine whether the differences between water status treatments on gs_max and dT were significant (at p < 0.05) from zero. The date effect was included in a three-way ANOVA with the aim to assess the specific time in which there were significant differences between water status treatments using the LSD post hoc test. In the second experiment, a linear function was fitted between CWSI vs. gs_max, Δtuber and DTB values using Sigmaplot software (11.0 version, Systat Software INC., Germany). Finally, one-way ANOVA for RCBD was used to compare DTB among irrigation timing treatments. All the statistical analyses were run using R software (v. 3.3.3, R Core Team).

Results

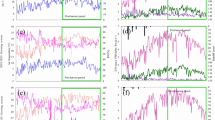

All the effects of the assessed factors on gs_max were significant at p < 0.05 except the interaction of water status treatment with time during May 20 and June 2 (Table 2). Control and drought plants showed gs_max average values which ranged between 0.11–0.34 and 0.08–0.29 mol H2O m−2 s−1, respectively. Maximums gs_max were detected from 07:00 to 12:00 hours before the moment (hereafter called abrupt fall of stomatal conductance—gs↓) when the increment of global radiation and VPD took values > 300 W m−2 and ≥ 0.5 kPa, respectively (Fig. 1a, c, e, g; Table 3). Higher gs_max average with significant differences between water treatments at p < 0.05 occurred mainly from 07:00 to 8:00 hours in most assessments, except during June 9, when there was an important difference just before noon (Fig. 1). The LSD post hoc test of the three-way ANOVA showed that the significant differences between water status treatments in gs_max occurred during 07:00–8:00 hours and 11:00–12:00 hours (Table 4).

Average values of maximum, light-saturated stomatal conductance (gs_max) and leaf minus air temperature (dT) along the day during the assessments corresponding to May 6 (a, b), May 20 (c, d), June 2 (e, f) and June 9 (g, h), 2016. Differences between water status treatments (control and water restriction in black and white bars, respectively) were assessed using LSD post hoc test (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n.s.p > 0.05). Vertical arrow marks the moment where significant gs_max reduction and dT increment were detected

All effects of the assessed factors on dT were significant (p < 0.05) except the water status treatment during May 20 (Table 2). Control and drought plants showed dT average values with ranges between − 0.4–4.3 and 0.2–5.5 °C, respectively. After gs↓ moment, dT took maximum values from 11:00 to 15:00 h (Fig. 1b, d, f, h; Table 3). Maximum dT differences between water treatments were mainly detected after gs↓ moment between 09:00 and 15:00 hours (Fig. 1). The moment with higher significant differences (at p < 0.05) between water status treatments in dT detected by the LSD post hoc test was during 15:00–16:00 hours followed by 11:00–12:00 and 09:00–10:00 (Table 4).

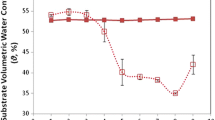

CWSI decreased linearly when plotted against gs_max (R2 = 0.82), Δtuber (R2 = 0.55) and DTB (R2 = 0.82) (Fig. 2). DTB was significantly affected by irrigation timing treatments (F = 15.7, p < 0.05), where average reduction in relation to the control was − 35.84 ± 9.72 and − 64.38 ± 7.04 for T1 and T2, respectively (Fig. 3).

Average dry tuber biomass (± standard error) comparing control (C), and two irrigation treatments watered when the average value of maximum light saturated stomatal conductance ≤ 0.15 (T1) and 0.05 (T2) mol H2O m−2 s−1, respectively. Different letters mean significant differences (at p < 0.05) detected by an ANOVA test

Discussion

Appropriate Time of the Day for Water Status Assessments Using Infrared Thermometry in Humid Environments

A high diffuse radiation component caused by the presence of clouds or aerosols contents in the atmosphere induces an increment in carbon assimilation efficiency in plants (Bunce 1984) promoting a rise in the ecosystem productivity (Huang et al. 2014). In fact, in the humid Peruvian Central Coast, Quiroz et al. (2017) reported higher light use efficiency (5.4 g MJ−1) for potatoes, compared to other agroecologies (Haverkort and Struik 2015), confirming the capability of this crop to optimize carbon assimilation (A) under humid environments. Moreover, in the same ecosystem and after assessing A maximum (highly correlated to gs_max, Ramírez et al. 2016a) during the day, Ramírez et al. (2016b) reported a peak in gas exchange early morning with an important reduction at noon in agreement with other studies (Dwelle et al. 1981). Potato has been typified as an isohydric crop (Obidiegwu et al. 2015) due to its stomatal closure sensitiveness (Vos and Oyarzún 1987) to soil water deficit maintaining leaf water potential through abscisic acid mediation (Liu et al. 2005). This strong stomatal closure characteristic reported for clear environments has been used to propose in this crop the monitoring of leaf (commonly assessed at dawn) or stem (Zakaluk and Sri Ranjan 2006; Byrd et al. 2014) water potential at noon (or close to this time). However, under humid environments with low VPD, maximum stomatal closure during the day depends on radiation increments and VPD (Table 2). The intensity of the inverse relationship between stomatal conductance and VPD varies among different plant species (Turner et al. 1984). Under low VPD environments, it has been reported that stomatal closure sensitivity to VPD increases (Vos and Groenwold 1989; Cunningham 2004); consistent with this finding, the results shown in this study suggest that under environments with low VPD (ranged 0.1–1.2 kPa, Table 2), potato presents an acute stomatal closure sensitivity to steep rises in this variable as well as to radiation (Fig. 1). Water restriction enhances stomatal closure sensitivity with increments in radiation during the day as has been reported in conditions with low VPD in European potato genotypes (Vos and Groenwold 1989). Under humid environments, assessing gs_max during the morning before gs↓ facilitates detecting differences in potatoes under water restriction and is thus recommended. The higher values registered for dT contrasts the response obtained for gs_max. While dT is characterized by negative values, showing negative correlation with VPD increments in some crops (Idso et al. 1981) including potato (Stark et al. 1991), dT values in this study were positive and in agreement with other findings in cereals (Amani et al. 1996). In one study carried out under an environment with low VPD values (0.1–1.1 kPa) in Dundee-Scotland, Prashar et al. (2013) reported canopy temperatures (ranged from ≈ 15 to ≈ 22 °C) higher than the atmospheric temperature (ranged from 12.5 to 13.8 °C) when assessing 188 potato genotypes, supporting the evidence that this crop is able to show positive dT values. Furthermore, using the cultivar UNICA in a dry environment in Southern Peru (with 4.4 kPa of VPD average maximum), Ramírez et al. (2016a) detected average dT values from 2.5 to 9.8 °C for plants either well irrigated or under severe water restriction, respectively. The controversial findings about dT values in this crop invite further research on stomatal sensitivity and its relationship with thermal emissions. In this study, the high intensity of stomatal closure is preceded by higher thermal emissions and concomitant positive dT increments consistent with an isohydric behaviour and stomatal closure sensitiveness under cloudy and low VPD environments.

Thresholds for Watering Timing Determination in Potato

The high correlation found between CWSI and gs_max, Δtuber and DTB (Fig. 2), (the latter two deemed as traits highly related to water status in potato; Erdem et al. 2005; Rud et al. 2014; Ramírez et al. 2015, 2016a), suggests that CWSI could be used as an important tool to define irrigation schedules under humid conditions. Ramírez et al. (2016a) proposed a CWSI value of 0.4 as a conservative threshold for potato irrigation in dry environments with clear atmosphere. However, this CWSI corresponds approximately to 0.4 mol H2O m−2 s−1 of gs_max, more than twice the value proposed by Flexas et al. (2004, 2006) for an optimum irrigation. In agreement with this observation, in this study, the treatment with irrigation timing using 0.15 mol H2O m−2 s−1 as a threshold showed important potato yield reduction in relation to the control (Fig. 3), suggesting that under humid environments, potatoes must be irrigated with lower thresholds than 0.3 to 0.4 CWSI values, corresponding to gs_max values higher than 0.3 mol H2O m−2 s−1.

Conclusion

Under humid environments, characterized by low VPD values and abrupt changes in radiation intensity, potato shows high stomatal sensitiveness with dramatic closure after gs↓ and a concomitant thermal emission increment. This dramatic change must be considered when scheduling appropriate timings, within a day, for estimating gs_max and canopy temperature by infrared radiometry as indicators of water deficit in the plant. For the present study, early-morning, noon and close to 15:00 h were the most suitable moments for water status characterization using both descriptors. At higher spatial scales, CWSI is deemed a more suitable variable for water status definition in this crop allowing appropriate irrigation schedules. Based on our findings, we suggest values < 0.3–0.4 as thresholds for this purpose. Furthermore, keeping plants with gs_max values higher than 0.3 mol H2O m−2 s−1 guarantees the highest tuber yield. Finally, assessing leaf-canopy minus atmosphere temperatures requires further inspection prior to recommending it as a tool to characterize the isohydric behaviour of diverse germplasm, for assessing stomatal sensitiveness in the large potato panels evaluated by potato breeding programs globally.

References

Ahmadi SH, Andersen MN, Plauborg F, Poulsen RT, Jensen CR, Sepaskhah AR, Hansen S (2010) Effects of irrigation strategies and soils on field grown potatoes: yield and water productivity. Agric Water Manag 97:1923–1930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2010.07.007

Amani I, Fischer RA, Reynolds MP (1996) Canopy temperature depression association with yield of irrigated spring wheat cultivars in a hot climate. J Agron Crop Sci 176:119–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037X.1996.tb00454.x

Beresford-Jones D, Pulle AG, Whaley OQ, Moat J, Chauca G, Cadwallader L, Arce S, Orellana A, Alarcón C, Gorrit M, Maita PK, Sturt F, Dupeyron A, Huaman O, Lane KJ, French C (2015) Re-evaluating the resource potential of Lomas fog oasis environments for preceramic hunter–gatherers under past ENSO modes on the south coast of Peru. Quat Sci Rev 129:196–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.10.025

Bunce JA (1984) Effects of humidity on photosynthesis. J Exp Bot 35:1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/35.9.1245

Byrd SA, Rowland DL, Bennett J, Zotarelli L, Wright D, Alva A, Nordgaard J (2014) Reductions in a commercial potato irrigation schedule during tuber bulking in Florida: physiological, yield, and quality effects. J Crop Improv 28:660–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427528.2014.929059

Cabello R, De Mendiburu F, Bonierbale M, Monneveux P, Roca W, Chujoy E (2012) Large-scale evaluation of potato improved varieties, genetic stocks and landraces for drought tolerance. Am J Potato Res 89:400–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-012-9260-5

Cunningham SC (2004) Stomatal sensitivity to vapour pressure deficit of temperate and tropical evergreen rainforest trees of Australia. Trees 18:399–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-004-0318-y

Dwelle RB, Kleinkopf GE, Pavek JJ (1981) Stomatal conductance and gross photosynthesis of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) as influenced by irradiance, temperature, and growth stage. Potato Res 24(1):49–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02362016

Erdem T, Halim Orta A, Erdem Y, Okursoy H (2005) Crop water stress index for potato under furrow and drip irrigation systems. Potato Res 48:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02733681

FAO (2018) FAOSTAT Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC

Flexas J et al (2004) Understanding down-regulation of photosynthesis under water stress: future prospects and searching for physiological tools for irrigation management. Ann Appl Biol 144:273–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.2004.tb00343.x

Flexas J, Bota J, Galmés J, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbó M (2006) Keeping a positive carbon balance under adverse conditions: responses of photosynthesis and respiration to water stress. Physiol Plant 127:343–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00621.x

Foti S, Mauromicale G, Ierna A (1995) Influence of irrigation regimes on growth and yield of potato cv. Spunta. Potato Res 38:307–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02357733

Gutiérrez-Rosales RO, Espinoza-Trelles JA, Bonierbale M (2007) UNICA: variedad Peruana para mercado fresco y papa frita con tolerancia y resistencia para condiciones climáticas adversas. Rev Latinoam Papa 14:41–50

Harris PM (1992) The Potato Crop: The scientific basis for improvement. Springer, Netherlands: XVIII, 909. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-2340-2

Haverkort AJ, Struik PC (2015) Yield levels of potato crops: recent achievements and future prospects. Field Crop Res 182:76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2015.06.002

Huang K, Wang S, Zhou L, Wang H, Zhang J, Yan J, Zhao L, Wang Y, Shi P (2014) Impacts of diffuse radiation on light use efficiency across terrestrial ecosystems based on eddy covariance observation in China. PLoS One 9:e110988. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110988

Idso SB, Jackson RD, Pinter PJ, Reginato RJ, Hatfield JL (1981) Normalizing the stress-degree-day parameter for environmental variability. Agric Meteorol 24:45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-1571(81)90032-7

Ierna A, Mauromicale G (2006) Physiological and growth response to moderate water deficit of off-season potatoes in the Mediterranean environment. Agric Water Manag 82:193–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2005.05.005

Jackson RD, Idso SB, Reginato RJ, Pinter PJ (1981) Canopy temperature as a crop water stress indicator. Water Resour Res 17:1133–1138. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR017i004p01133

Jones HG (1999) Use of infrared thermometry for estimation of stomatal conductance as a possible aid to irrigation scheduling. Agric For Meteorol 95:139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(99)00030-1

Jones HG (2004a) Application of thermal imaging and infrared sensing in plant physiology and ecophysiology. Adv Bot Res 41:107–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2296(04)41003-9

Jones HG (2004b) Irrigation scheduling: advantages and pitfalls of plant-based methods. J Exp Bot 55:2427–2436. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erh213

Kramer PJ (1983) 12—Water deficits and plant growth. In: Water relations of plants. Academic Press, pp 342–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-425040-6.50015-1

Kramer PJ (1988) Measurement of plant water status: historical perspectives and current concerns. Irrig Sci 9:275–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00296703

Liu F, Jensen CR, Shahanzari A, Andersen MN, Jacobsen S-E (2005) ABA regulated stomatal control and photosynthetic water use efficiency of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during progressive soil drying. Plant Sci 168:831–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.10.016

Medrano H, Escalona JM, Bota J, GulÍAs J, Flexas J (2002) Regulation of photosynthesis of C3 plants in response to progressive drought: stomatal conductance as a reference parameter. Ann Bot 89:895–905. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcf079

Meron M, Tsipris J, Orlov V, Alchanatis V, Cohen Y (2010) Crop water stress mapping for site-specific irrigation by thermal imagery and artificial reference surfaces. Precis Agric 11:148–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-009-9153-x

Möller M et al (2007) Use of thermal and visible imagery for estimating crop water status of irrigated grapevine. J Exp Bot 58:827–838. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erl115

Monneveux P, Ramírez DA, Pino M-T (2013) Drought tolerance in potato (S. Tuberosum L.): can we learn from drought tolerance research in cereals? Plant Sci 205-206:76–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.01.011

Obidiegwu J, Bryan G, Jones H, Prashar A (2015) Coping with drought: stress and adaptive responses in potato and perspectives for improvement. Front Plant Sci 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00542

Prashar A, Yildiz J, McNicol JW, Bryan GJ, Jones HG (2013) Infra-red thermography for high throughput field phenotyping in Solanum tuberosum. PLoS One 8:e65816. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065816

Quiroz R, Loayza H, Barreda C, Gavilán C, Posadas A, Ramírez DA (2017) Linking process-based potato models with light reflectance data: does model complexity enhance yield prediction accuracy? Eur J Agron 82:104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2016.10.008

Ramírez DA, Rolando JL, Yactayo W, Monneveux P, Quiroz R (2015) Is discrimination of 13C in potato leaflets and tubers an appropriate trait to describe genotype responses to restrictive and well-watered conditions? J Agron Crop Sci 201:410–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/jac.12119

Ramírez DA, Yactayo W, Rens LB, Rolando JL, Palacios S, De Mendiburu F, Mares V, Barreda C, Loayza H, Monneveux H, Zotarelli L, Khan A, Quiroz R (2016a) Defining biological thresholds associated to plant water status for monitoring water restriction effects: stomatal conductance and photosynthesis recovery as key indicators in potato. Agric Water Manag 177:369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2016.08.028

Ramírez DA, Monneveux P, Quiroz R (2016b) Mitigando los efectos de la sequía en papa: Algunos alcances y retos In: Pino MT (Ed) Estrés hídrico y térmico en papa, avances y protocolos Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, pp 115–129

Rolando JL, Ramírez DA, Yactayo W, Monneveux P, Quiroz R (2015) Leaf greenness as a drought tolerance related trait in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Environ Exp Bot 110:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.09.006

Rud R, Cohen Y, Alchanatis V, Levi A, Brikman R, Shenderey C, Heuer B, Markovitch T, Dar Z, Rosen C, Mulla D, Nigon T (2014) Crop water stress index derived from multi-year ground and aerial thermal images as an indicator of potato water status. Precis Agric 15:273–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-014-9351-z

Stark JC, Wright JL (1985) Relationship between foliage temperature and water stress in potatoes. Am Potato J 62:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02903463

Stark JC, Pavek JJ, McCann I (1991) Using canopy temperature measurements to evaluate drought tolerance of potato genotypes. Am Soc Hortic Sci 116(3):412–415

Steduto P, Hsiao TC, Fereres E, Raes D (2012) Crop yield response to water. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 66, p 500

Turner NC, Schulze E-D, Gollan T (1984) The responses of stomata and leaf gas exchange to vapour pressure deficits and soil water content. Oecologia 63:338–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00390662

van Loon CD (1981) The effect of water stress on potato growth, development, and yield. Am Potato J. 58:51–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02855380

Vos J, Groenwold J (1989) Characteristics of photosynthesis and conductance of potato canopies and the effects of cultivar and transient drought. Field Crop Res 20:237–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4290(89)90068-3

Vos J, Oyarzún PJ (1987) Photosynthesis and stomatal conductance of potato leaves—effects of leaf age, irradiance, and leaf water potential. Photosynth Res 11:253–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00055065

Zakaluk R, Sri Ranjan R (2006) Artificial neural network modelling of leaf water potential for potatoes using RGB digital images: a greenhouse study. Potato Res 49:255–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-007-9021-x

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nikolai Alarcon and Jesus Zamalloa for their technical support.

Funding

The financial support for this research was provided by Programa Nacional de Innovación Agraria (PNIA) with the Project No. 016-2015-INIA-PNIA/UPMSI/IE “Uso efectivo del agua en el cultivo de papa en zonas áridas: Mejorando el manejo del riego mediante el monitoreo del estatus hídrico para enfrentar al Cambio Climático”. The research was conducted under and received complementary funds from the CGIAR Research Programs on Root, Tuber and Bananas (RTB). For a list of CGIAR Fund donors, please see: http://www.cgiar.org/whowe-are/cgiar-fund/fund-donors-2/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rinza, J., Ramírez, D.A., García, J. et al. Infrared Radiometry as a Tool for Early Water Deficit Detection: Insights into Its Use for Establishing Irrigation Calendars for Potatoes Under Humid Conditions. Potato Res. 62, 109–122 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-018-9400-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-018-9400-5