Abstract

In recent years, a “third mission” pursued by universities, i.e. knowledge transfer to industry and society, has become more important as a determinant of enhancements in economic growth and social welfare. In the vast world of technology transfer practices implemented by universities, the establishment and management of university venture capital and private equity funds (UFs) is largely unknown and under-researched. The focus of this work is to provide a detailed description of this phenomenon from 1973 to 2010, in terms of which universities set-up UFs, their target industries and the investment stages of portfolio companies, which types of co-investors are involved in the deals, and which are the determinants of UFs’ ultimate performances. The picture offers us the opportunity to draw some implications about the relevance of UFs in different contexts (i.e. Europe and the United States) and provide to interested stakeholders with some useful guidelines for future development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As explained by Lerner (2005, p. 49): ‘The first modern venture capital firm, American Research and Development (ARD), was designed to focus on technology-based spinouts from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As envisioned by its founders, who included MIT President Karl Compton, Harvard Business School Professor Georges F. Doriot, and Boston-area business leaders, this novel structure would be best suited to commercialize the wealth of military technologies developed during World War II’.

Universities can also participate in publicly-funded research joint ventures with entrepreneurial firms and/or corporations (Colombo et al. 2009; Barajas et al. 2012). For a comprehensive review of technology transfer mechanisms, see Autio and Laamanen (1995), Wright et al. (2004), Siegel (2006), and Phan and Siegel (2006).

For instance, in April 2012, in Washington DC, Acceleprise was created. Acceleprise is a newly formed technology accelerator targeting young high-tech entrepreneurial companies, whose three founders avail themselves of several mentors, including VC investors and industry experts. Each selected company receives a seed investment ($ 30,000 in exchange of 5 % equity), an office space, coaching, business and managerial consultancy services and participates to dedicated workshops with potential investors and interested partners.

More specifically, we refer to the financial vehicles put in place by the parent universities. In some cases, these financial vehicles invest in portfolio companies through more than one fund. For the sake of simplicity, we refer to the financial vehicles as UFs, whichever the number of funds used by the vehicle.

As notable exceptions, in US, there are UFs which are managed by teams formed by graduate (MBA) students. The University Venture Fund of University of Utah was the first one (see the article “Students running a VC fund? The University Venture Fund says yes” by Cheryl Conner appeared in Forbes on January 19th, 2013). Also the UF BR Ventures at Cornell University adopted the same model.

The establishment of a formal advisory committee is a typical trait of professional VC funds (e.g. Sahlman 1990).

When active, ARCH Development Partners LLC always maintained its geographical interest on the US Midwest States with a primary focus in Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan. Until 2011, Imperial Innovations only invested in businesses built on intellectual property developed at the Imperial College. Since then, it enlarged its operations to the University of Cambridge, the University of Oxford and the University College London. The UFs created by the University of Manchester and the Université Catholique de Louvain have always maintained the exclusive aim of increasing the spin-out rate from the corresponding parent universities (see the institutional websites for further references).

Incidentally note that this UF contributed to create some legendary companies: e.g., the storage media manufacturing corporation Dysan founded by C. Norman Dion in 1973 in a garage that during 1980s became a 500 Fortune company with more than 1,200 employees.

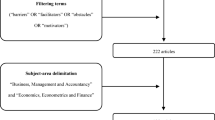

The extraction refers to February 2010.

As said in the main text, the Thompson One database is considered one of the most reputed sources of information for VC activity at global level. Needless to say, this does not imply that the database is able to trace every single VC (and possibly UF) investment all over the world (see Ivanov and Xie 2010: p. 135).

We exclude investors classified by the Thomson One database as “Incubators”. The Thomson One database defines an Incubator as “an entity designed to nurture business concepts or new technologies to the point that they become attractive to VC investors. An incubator usually provides both physical space, and some or all of the other services needed for a business concept to be developed”.

We follow the industry classification provided by the Thomson One database. The only notable exception is represented by the grouping of some specific industries into two macro categories. More specifically, we define: (i) a “Non high-tech” industry that includes Business Services, Construction, Consumer Related and Other; and (ii) an “ICT” industry that includes Communications, Computer Hardware, Computer Software, Computer Other and Internet Specific.

As suggested by Da Rin et al. (2011, pp. 74–75): ‘obtaining data for computing returns turns out to be a difficult task. VC firms are not required by regulations to disclose their investments, distributions or returns […]. As a consequence there are no comprehensive databases for valuation and returns data. The main data sources are those VCs or LPs who voluntarily provide information, either to the commercial data providers, or directly to researchers. LPs and VCs may thus choose whether to report, and if so, what data to report. The main problem is reporting bias, i.e., that fact that reporting is likely to be (positively) correlated with performance’. This problem is extremely exacerbated with regard to UFs. Even through the use of the Thomson One database, we have to face a strong reporting bias, which does not allow us (like other scholars in the field) to estimate UFs’ returns.

As highlighted by Samila and Sorenson (2011), the returns earned by the limited partners (cash inflows distributed by the general partner of the VC fund after the exit from the portfolio companies) predict well the supply of VC. Given that the IRR is highly correlated with the return earned by the limited partners, the slowdown in the returns of US VC funds in the post-2000 period is associated to a decrease in US VC investment activity. For more details on (EU and US) VC funds’ returns, see also Machado Rosa and Raade (2006).

These rankings of the top universities across the globe employ 13 separate performance indicators designed to capture the full range of university activities, i.e. teaching, research, knowledge transfer. These 13 elements are brought together into separate categories (i.e. Teaching, Research, Citations, Industry income, Innovation, International outlook and Staff’s internationalization. For more details, please refer to: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/).

The extant literature has justified co-invested deals through a reduction in information asymmetries (Casamatta and Haritchabalet 2007; Lerner 1994), an exploitation of complementary value-adding resources, skills, networks and industry expertise (Bygrave 1987), a reduction in overall portfolio risk (Lerner 1994), a higher influence in control rights in co-financed portfolio companies (Kaplan and Strömberg 2003), a reduction in agency problems with portfolio companies’ top management team (Admati and Pfleiderer 1994), and a signal to capital markets of the quality of the focal portfolio company. Especially with regard to the latter reason, Tian (2012) finds that co-financing increases the likelihood to have a successful exit.

We provide additional evidence on the specific typology of co-investors in Sect. 5.7.1.

The median value is 8 years for the US funds and 5 years for the EU ones, respectively. Results do not change if we use the mean instead of the median as threshold values.

In order to measure UF's experience we resort to other different proxies as the number of years from the first investment in our dataset, the number of years from UF's vintage year and the age of the UF fund. Results obtained by the use of these different proxies are qualitatively similar to those reported in Tables 8-10 and are omitted from the authors for the sake of synthesis. They are available from the authors upon request.

In order to have minimally reliable statistics, the ratio between the number of observations and the number of variables must be always greater than 5.

In particular, we estimated the Model (IV) in Table 12 by replacing the variable Coinvestors i with a series of dummy variables indicating the type of co-investors (i.e. BVC i , CVC i , GVC i , and BA i ). We do not include a dummy variable IVC i because all UFs co-invested with (at least) an IVC investor in their life. In an alternative specification, we substituted these dummy variables with the number of co-investors in each category (nBVC i , nCVC i , nGVC i , and nBA i , respectively). For the sake of brevity, results are only discussed in the text and not reported in tables (they are available upon request from the authors). Needless to say, note also that this further explorative exercise has to be viewed as purely ancillary to the previous analysis about the effects of the number of co-investors on the different exit modes of UFs’ portfolio companies. For this reason, it has been confined to the only dependent variable (i.e. “Acquisitions”) for which we detect a significant impact of the variable Coinvestors i .

Andrea Huspeni “How To Score A Meeting With An Angel Investor”, Business Insider, 7/20/2012.

In other words, we consider only companies included in the categories: “Still in portfolio”, “IPOs” and “Acquisitions” (see Table 6). Companies exited in earlier periods (e.g., 1970s, 1980s) show a higher probability to have missing information at both founder- and firm-level. This may be also due to the fact that some companies could not be longer in operation. Obviously, it is very hard to collect data on companies classified as “Failures” by the Thompson One database. For this reason, we excluded these latter from the beginning of the hand-collection data search on which the analysis of this section is based.

Both Europe and the US use the same threshold of less than 10 employees to define micro-firms.

The threshold of 50 (250) employees is commonly used by the European Union to define a small (medium-sized) firm.

References

Admati, A. R., & Pfleiderer, P. (1994). Robust financial contracting and the role of venture capitalists. Journal of Finance, 49, 371–402.

Aernoudt, R. (2004). Incubators: Tool for entrepreneurship? Small Business Economics, 23, 127–135.

Algieri, B., Aquino, A., & Succurro, M. (2013). Technology transfer offices and academic spin-off creation: The case of Italy. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38, 382–400. doi:10.1007/s10961-011-9241-8.

Atkinson, S. H. (1994). University-affiliated venture capital funds. Health Affairs, 13, 159–175.

Autio, E., & Laamanen, T. (1995). Measurement and evaluation of technology transfer: Review of technology transfer mechanisms and indicators. International Journal of Technology Management, 10, 643–664.

Barajas, A., Huergo, E., & Moreno, L. (2012). Measuring the economic impact of research joint ventures supported by the EU Framework Programme. Journal of Technology Transfer, 37, 917–942.

Barry, C. B., Muscarella, C. J., Peavy, J. W., III & Vetsuypens, M. R. (1990). The role of venture capital in the creation of public companies: Evidence from the going-public process. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 447–471.

Benson, D., & Ziedonis, R. H. (2008). Corporate venture capital as a window on new technologies: Implications for the performance of corporate investors when acquiring startups. Organization Science, 20, 352–367.

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2006). Entrepreneurial universities and technology transfer: A conceptual framework for understanding knowledge-based economic development. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31, 175–188.

Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2013). Venture capital investor type and the growth mode of new technology-based firms. Small Business Economics, 40, 527–552.

Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G., & Quas, A. (2012). Patterns of venture capital investments in Europe. Working paper, Politecnico di Milano. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1920351 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1920351. Accessed 7 Jan 2013.

Bertoni, F., & Croce, A. (2011). Policy reforms for venture capital in Europe. In M. G. Colombo, L. Grilli, L. Piscitello, & C. Rossi (Eds.), Science and innovation policy for the new knowledge economy (pp. 196–229). Cheltenham Glos (UK): Elgar.

Bottazzi, L., & Da Rin, M. (2002). Venture capital in Europe and the financing of innovative companies. Economic Policy, 17, 231–269.

Bottazzi, L., Da Rin, M., & Hellmann, T. F. (2004). The changing face of the European venture capital industry: Facts and analysis. Journal of Private Equity, 7, 26–53.

Bottazzi, L., Da Rin, M., & Hellmann, T. F. (2008). Who are the active investors? Evidence from the venture capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 28, 488–512.

Brander, J. A., Amit, R., & Antweiler, W. (2002). Venture-capital syndication: Improved venture selection vs. the value-added hypothesis. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 11, 423–452.

Bygrave, W. D. (1987). Syndicated investments by venture capital firms: A networking perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 2, 139–154.

Casamatta, C., & Haritchabalet, C. (2007). Experience, screening and syndication in venture capital investments. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 16, 368–398.

Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: Organizational pathways of transformation. New York: Pergamon.

Colombo, M. G., & Delmastro, M. (2002). How effective are technology incubators? Evidence from Italy. Research Policy, 31, 1103–1122.

Colombo, M. G., Grilli, L., Murtinu, S., Piscitello, L., & Piva, E. (2009). Effects of international R&D alliances on performance of high-tech start-ups: A longitudinal analysis. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3, 346–368.

Croce, A., Martí, J., & Murtinu, S. (2013). The impact of venture capital on the productivity growth of European entrepreneurial firms: ‘Screening’ or ‘value added’ effect? Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 489–510.

D’Este, P., & Perkmann, M. (2011). Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. Journal of Technology Transfer, 36, 316–339.

Da Rin, M., Hellmann, T. F., & Puri, M. (2011). A survey of venture capital research. TILEC Discussion Paper No. 2011-044. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1942821 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1942821. Accessed 25 May 2013.

Da Rin, M., Nicodano, G., & Sembenelli, A. (2006). Public policy and the creation of active venture capital markets. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 1699–1723.

Etzkowitz, H. (2003). Research groups as ‘quasi-firms’: The invention of the entrepreneurial university. Research Policy, 32, 109–121.

Etzkowitz, H., Webster, A., Gebhardt, C., & Terra, B. R. C. (2000). The future of the university and the university of the future: Evolution of ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Research Policy, 29, 313–330.

European Commission. (1995). Green paper on innovation. Communications from the Commission, Bruxelles, http://europa.eu/documents/comm/green_papers/pdf/com95_688_en.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2013.

European Commission. (2007). Improving knowledge transfer between Research Institutions and industry across Europe: Embracing Open Innovation, COM(2007) 182 final, Bruxelles, http://ec.europa.eu/invest-in-research/pdf/com2007182_en.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2013.

European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Communications from the Commission, Bruxelles, 3/3/2010, http://www.elgpn.eu/elgpndb/fileserver/files/39. Accessed 7 Jan 2013.

European Parliament. (2012). Potential of Venture Capital in the European Union. Directorate General for Internal Policies. Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy Industry, Research and Energy, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/studiesdownload.html?languageDocument=EN&file=66851. Accessed 7 Jan 2013.

Florida, R., & Cohen, W. M. (1999). Engine or infrastructure? The university role in economic development. In L. M. Branscomb, F. Kodama, & R. Florida (Eds.), Industrializing knowledge: University-industry Linkages in Japan and the United States (pp. 589–610). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fukugawa, N. (2006). Science parks in Japan and their value-added contributions to new technology-based firms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24, 381–400.

Gompers, P., Kovner, A., & Lerner, J. (2009). Specialization and success: Evidence from venture capital. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18, 817–844.

Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (1999). An analysis of compensation in the US venture capital partnership. Journal of Financial Economics, 51, 3–44.

Groh, A. P., Liechtenstein, H., & Lieser, K. (2011). The European venture capital and private equity country attractiveness indices. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16, 205–224.

Hair, J. F, Jr, Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hochberg, Y. V., Ljungqvist, A., & Lu, Y. (2007). Whom you know matters: Venture capital networks and investment performance. Journal of Finance, 62, 251–301.

Ivanov, V. I., & Xie, F. (2010). Do corporate venture capitalists add value to startup firms? Evidence from IPOs and acquisitions of VC-backed companies. Financial Management, 39, 129–152.

Jeng, L. A., & Wells, P. C. (2000). The determinants of venture capital funding: Evidence across countries. Journal of Corporate Finance, 6, 241–289.

Kaplan, S. N., & Schoar, A. (2005). Private equity returns: Persistence and capital flows. Journal of Finance, 60, 1791–1823.

Kaplan, S. N., Sensoy, B., & Strömberg, P. (2002). How well do venture capital databases reflect actual investments? Working paper, University of Chicago. http://ssrn.com/abstract=939073 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.939073. Accessed 7 Jan 2013.

Kaplan, S. N., & Strömberg, P. (2003). Financial contracting theory meets the real world: An empirical analysis of venture capital contracts. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 281–315.

Kelly, R. (2011). The performance and prospects of European venture capital. EIF working paper, 2011(09), 1–24.

Knockaert, M., Wright, M., Clarysse, B., & Lockett, A. (2010). Agency and similarity effects and the VC’s attitude towards academic spin-out investing. Journal of Technology Transfer, 35, 567–584.

Kortum, S., & Lerner, J. (2000). Assessing the contribution of venture capital to innovation. Rand Journal of Economics, 31, 674–692.

Lee, Y. S. (1996). ‘Technology transfer’ and the research university: A search for the boundaries of university-industry collaboration. Research Policy, 25, 843–863.

Lee, Y. S. (2000). The sustainability of university-industry research collaboration: An empirical assessment. Journal of Technology Transfer, 25, 111–133.

Leleux, B., & Surlemont, B. (2003). Public versus private venture capital: Seeding or crowding out? A pan-European analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 81–104.

Lerner, J. (1994). The syndication of venture capital investments. Financial Management, 23, 16–27.

Lerner, J. (1995). Venture capitalists and the oversight of private firms. Journal of Finance, 50, 301–318.

Lerner, J. (2002). When bureaucrats meet entrepreneurs: The design of effective ‘public venture capital’ programmes. Economic Journal, 112, F73–F84.

Lerner, J. (2005). The university and the start-up: Lessons from the past two decades. Journal of Technology Transfer, 30, 49–56.

Löfsten, H., & Lindelöf, P. (2002). Science parks and the growth of new technology-based firms: Academic-industry links, innovation and markets. Research Policy, 31, 859–876.

Machado Rosa, C. D., & Raade, K. (2006). Profitability of Venture Capital Investment in Europe and the United States. European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Economic Papers Number 245, ISSN 1725-3187.

Markman, G. D., Gianiodis, P. T., Phan, P. H., & Balkin, P. H. (2005). Innovation speed: Transferring university technology to market. Research Policy, 34, 1058–1075.

Martinelli, A., Meyer, M., & von Tunzelmann, N. (2008). Becoming an entrepreneurial university? A case study of knowledge exchange relationships and faculty attitudes in a medium-sized, research-oriented university. Journal of Technology Transfer, 33, 259–283.

Mian, S. A. (1996). Assessing value-added contributions of university technology business incubators to tenant firms. Research Policy, 25, 325–335.

Morandi, V. (2013). The management of industry–university joint research projects: How do partners coordinate and control R&D activities? Journal of Technology Transfer, 38, 69–92.

Phalippou, L., & Gottschalg, O. (2009). The performance of private equity funds. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 1747–1776.

Phan, P. H., & Siegel, D. S. (2006). The effectiveness of university technology transfer: Lessons learned, managerial and policy implications, and the road forward. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 2, 77–144.

Phan, P. H., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2005). Science parks and incubators: Observations, synthesis and future research. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 165–182.

Ritter, J. R. (2003). Differences between European and American IPO markets. European Financial Management, 9, 421–434.

Sahlman, W. A. (1990). The structure and governance of venture-capital organizations. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 473–521.

Samila, S., & Sorenson, O. (2011). Venture capital, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93, 338–349.

Shane, S. (2004). Academic Entrepreneurship: University Spinoffs and Wealth Creation. London: Edward Elgar.

Siegel, D. S. (Ed.). (2006). Technology entrepreneurship: Institutions and agents involved in university technology transfer (Vol. 1). London: Edward Elgar.

Siegel, D. S., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2003). Assessing the impact of university science parks on research productivity: Exploratory firm-level evidence from the United Kingdom. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21, 1357–1369.

Slaughter, S., & Leslie, L. L. (1997). Academic capitalism: Politics, policies, and the entrepreneurial university. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Soetanto, D. P., & Jack, S. L. (2013). Business incubators and the networks of technology-based firms. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38, 432–453. doi: 10.1007/s10961-011-9237-4.

Sørensen, M. (2007). How smart is smart money? A two-sided matching model of venture capital. Journal of Finance, 62, 2725–2762.

Stein, J. C. (1997). Internal capital markets and the competition for corporate resources. Journal of Finance, 52, 111–133.

Tian, X. (2012). The role of venture capital syndication in value creation for entrepreneurial firms. Review of Finance, 16, 245–283.

Wright, M., Birley, S., & Mosey, S. (2004). Entrepreneurship and university technology transfer. Journal of Technology Transfer, 29, 235–246.

Zarutskie, R. (2010). The role of top management team human capital in venture capital markets: Evidence from first-time funds. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 155–172.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Massimiliano Guerini for valuable assistance in the data collection process. We are thankful to the Editor Donald Siegel and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. Responsibility for any possible errors and deficiencies lies solely with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Croce, A., Grilli, L. & Murtinu, S. Venture capital enters academia: an analysis of university-managed funds. J Technol Transf 39, 688–715 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9317-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9317-8

Keywords

- University-managed funds

- University

- Venture capital and private equity

- Technology transfer

- Third mission

- Fund performance