Abstract

China is the largest worldwide potato producer where around half of the crops is planted in the semi-arid region frequently affected by water restriction. While innovative methods are needed for water-saving irrigation methods, the use of low-cost and environmental-friendly technology must be prioritised. In this study, potato production under drip irrigation (DI, commonly adopted to save water) was compared with partial root-zone drying furrow irrigation (PRD) using the same water volume per irrigation, in both methods. Two initiation timings (early and late) were tested under shelter and field conditions, the water supplied during every irrigation being 50% of the crop water demand calculated for furrow full irrigation (FI, as control). The comparison of both methods was done through the assessment of tuber fresh-yield and estimated economic and environmental (carbon footprint and irrigation water use efficiency, WUEi) benefits. Late PRD and DI produced the highest WUEi without significant yield reduction. PRD produced 3.1% higher net benefit than DI with an estimated CO2 emission of 3659 kg ha−1 CO2 (14% lower than DI). The input-output ratio (total input costs/yield output) for PRD was 0.4, which was 10% lower than DI. The study’s results suggested that PRD, with no less than 50% of the water applied in FI per application, not only maintained yield but could also increase revenues while saving water and reducing CO2 emissions, compared to DI. Such results might help reduce the pressure on the water reserves in semi-arid potato-producing areas in China. Notwithstanding, a scaling-up of PRD technology must be tested in those regions to substantiate the findings of this preliminary study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is the fourth most important food crop after maize, rice and wheat, and is cultivated widely in the world, with China as the largest potato-producing country accounting for 26.3% of global production (FAO 2018). In 2015, the government of China implemented a policy to push potato as a staple food, to guarantee food security and improve human nutrition and health requirements. The aim was to expand potato planting to more than 6.7 million ha by 2020 (CHNMOA 2015). This might exacerbate the current pressure on the use of water resources, since about 50% of potatoes cultivated in this country are grown under irrigation in semi-arid areas (Luo et al. 2015). Moreover, potato is considered sensitive to drought stress due to a shallow and inefficient root system (Stalham et al. 2007). Thus, the expansion of potato cultivation in water-scarce environments poses important research challenges.

In China, declining water resources have raised great public attention in agriculture, so innovative irrigation strategies are developed to save water and increase water use efficiency (WUE) in comparison to conventional irrigation methods (Qin et al. 2013; Zhang and Guo 2016; Giuliani et al. 2016). The government subsidises the implementation of Hi-Tech irrigation systems such as drip irrigation (DI), which in potato reduces soil moisture evaporation and prevents weed growth by supplying water mainly to the root zone (Wang et al. 2007; Qin et al. 2011; Xue et al. 2017). The adoption of DI in several crops has generated benefits such as yield increments (Deng et al. 2009; Kruzhilin et al. 2016), water saving by 30–70% (Zhao and Wang 2016; Ibrahim et al. 2016) and reduced fertiliser application by 10–40% (Li 2008, 2016) compared to furrow irrigation. However, the costs of DI are higher than those of furrow irrigation, when the whole system itself plus maintenance costs are included in the analysis (Shen et al. 2011). Furthermore, after harvest, some plastic residues (pipes, tubes) that are kept in the field become brittle polluting the environment (Yang et al. 2011). Moreover, it has been reported that because system maintenance demands a lot of time, mainly when canopy cover is at maximum, farmers are not able to detect water leaks (caused by insects or other factors) on time which may cause water loss and have a negative effect on plant growth (Chen and Du 2011). On the other hand, partial root-zone drying furrow irrigation (PRD) is considered a deficit irrigation strategy (Perry et al. 2017), which allows half of the root system to be irrigated while keeping the other half dry in each irrigation event, before rewetting the root zone by shifting irrigation to the dry side (Kang et al. 1997). PRD has been successfully applied to potato, reducing water by 30–50% with an increased WUE, without tuber yield reduction (Liu et al. 2006a, b; Saeed et al. 2008; Jovanovic et al. 2010; Xie et al. 2012; Yactayo et al. 2013, 2017). However, challenges for PRD include finding the appropriate timing, duration and intensity of the water restriction management in potato that stimulates some tolerance mechanism to avoid yield reduction (Monneveux et al. 2013). Recent findings, working in potatoes under pot (Saeed et al. 2008) and field (Xu et al. 2011; Yactayo et al. 2013, 2017) conditions, highlight that an early timing of the water restriction (starting at 6 weeks after planting) with PRD using 50% of the amount of water applied with full irrigation allows high WUE with no significant yield reductions through the activation of drought tolerance traits like osmotic adjustment.

While the benefits of furrow versus Hi-Tech irrigation methods have been reported in potato, these studies have not used the same amount of water (Erdem et al. 2005, 2006; Ati et al. 2012) or irrigation frequency (Kumar et al. 2009) in the comparisons. In this study, DI and PRD irrigation techniques were compared using similar amounts of water per equivalent treatments, under sheltered (to avoid unexpected rainfall effect which can bias the results) and field conditions. The metrics used for the comparative assessment included agronomic parameters and economic and environmental (estimated carbon footprint, irrigation WUE-WUEi) costs. Since the timing for initiating water restriction is an underexplored topic in potato water management (Monneveux et al. 2013), we made the aforementioned comparisons testing early and late DI and PRD initiation treatments. We hypothesised that PRD could show similar benefits in terms of water saving and tuber yield to DI but in a more economic and environmental friendly manner.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Site

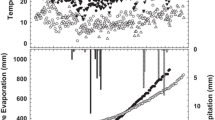

The field experiments were conducted from May 16 to September 13, 2013, in the experimental station of Zhangjiakou Academy of Agricultural Sciences (41° 04′ N, 114° 42′ E, 1505 masl), Zhangbei County, China. The climate is semi-arid with 4.0 ± 11.9 °C and 385.8 ± 20.4 mm of average annual temperature and precipitation, respectively, January (−14.6 ± 2.0 °C) and July (19.8 ± 1.0 °C) being the coldest and hottest months, respectively (2003–2014; Zhangjiakou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Meteorological Station). During the study period, the average, minimum and maximum daily temperatures and humidities were 16.3 ± 2.5 °C, − 4.5 °C and 31.2 °C and 66.8 ± 12.6% (Table 1). The soil texture was clay loam with field capacity and bulk density of 0.19 (w/w) and 1.44 g cm−3, respectively.

Experimental Design

The potato cultivar tested was Shepody (CIP code 801079) which is considered drought sensitive (Zhou and Zhang 2015). The experiment was carried out under open field and rain-proof shelter conditions, the latter installed to avoid interference with tested water treatments from potential rainfall water. For both conditions, there were five blocks with five plots (5 × 3.5 m2) per block. Each plot had five ridges (0.7 m apart from each other). Potatoes were planted at a distance of 0.3 m resulting in a plant density of 4.8 plants m−2. The irrigation treatment was randomly assigned to each plot in the block (randomised block design). The irrigation treatments (details below) were as follows: full furrow irrigation (FI) supplying 100% of the water demand; early PRD and early DI with 50% water amount of FI (E-PRD50 and E-DI50), starting the irrigation after but close to tuber initiation onset (TIO around 43 DAP); and late PRD and late DI with 50% water amount of FI (L-PRD50 and L-DI50), starting the irrigation 2 weeks after TIO. Tuber initiation was visually detected by removing and replacing soil from randomly chosen border plants.

Irrigation Management

Twenty transparent plastic water tanks (300 L of capacity, graduated at 5 L) placed at 1.5 m height were used for both open field and shelter conditions. Four tanks were placed per block, one for FI, one for PRD and two for DI plots. The water supply for the tanks came from a water reservoir (10,000 L capacity) placed 40 m from the experiment. From planting to the beginning of the irrigation treatment period, the only water supplied was 34.7 mm from a rainfall event after which the rain-proof shelter was used and the treatments were initiated. When the water treatment started, both PRD and DI received the same amount of water in each irrigation event. Water demand was assessed to define the required irrigation quantity (I, mm) in FI every 10 days, as follows:

Where θFC is gravimetric soil moisture at field capacity (0.19), θact is actual gravimetric soil moisture (%), BD is soil bulk density (1.44 g cm−3), RD is root depth (0.25 m), and WA is wetted area (distance between rows/wetted perimeter) (see Fig. 1). Before each irrigation, two representative soil samples in every FI plot were collected from the middle of the two plants in the respective centre ridges at 0.25 m depth to calculate θact. This soil sampling depth assumed that the main roots were distributed between 0.2–0.3 m and that the soil water potential at a depth of 0.25 m could represent the trend of 0–0.5 m in depth (Guo et al. 2015). Soil samples were weighed and dried (at 105 °C for 24 h) and re-weighed. Then, the water demand for FI treatment was calculated using Formula (1) and water was pumped (pump of 7.5 kW, 380 V, 52 m lift and 20 m3 h−1 capacity, Tianjin Weiyi Electrical Machinery Factory, Tianjin, China) from the reservoir to the tanks. For volumes less than 5 L, a small container (15 L, graduated every 1 L) was used to add the remaining quantity of water to the tank. After the water amount for FI was estimated, 50% of this quantity was provided to the tanks which supplied water for plots under PRD and DI irrigation treatments in tandem.

Plastic barriers were buried in the soil in the perimeter of the sheltered area and down to 30 cm among plots to avoid lateral water flow. PRD consisted in irrigating only one side of the root system, while keeping the other side dry in each irrigation event, alternating sides every 10 days. A drip irrigation system was installed in plots with DI treatments consisting of drip taps with emitters (with a flow rate of 1.38 L h−1) spaced at 0.3 m on the top of the ridge. As in furrow irrigation, 50% of estimated FI water demand was placed in the respective reservoirs and delivered through the DI system.

The rain-proof shelter was 90 m long and 8.5 m wide, but the actual area used for the experiment was 88.2 × 5 m2 to avoid boundary effect. The shelter was made of two aluminium arched frames (1.5 mm thick) which consisted of a shoulder (1.6 m height) and roof (2.5 m top height) (see Fig. 2). Only the roof from 0.8 m above the ground was covered by a transparent plastic film to prevent rainfall, and a nylon net (0.425 mm) was used for the whole frame to reduce the entrance of pest and disease vectors. The plastic film was also buried to 0.3 m depth inside the frame and kept 0.65 m away from the border of the frame to prevent entry of outside water.

Schematic representation of the measurement of the average wetted perimeter. Transversal image of a row: a before irrigation; b during irrigation; c immediately after the irrigation where it is possible to distinguish the wetted part of the row (dark colour); d measure of the wetted perimeter using a flexible metric tape up to 20 sampling points or rows (blue dotted line) in the plot, the average value can be used as the plot wetted perimeter

Agronomic Practices

Compound fertiliser (15:15:15) was applied at a rate of 495 kg ha−1 before planting, giving 74.3:74.3:74.3 kg ha−1 of N:P2O5:K2O. To avoid soil-borne disease affecting emergence, seed tubers were treated with 70% of thiophanate methyl wettable powder: talcum powder (1:25) at a dose of 6 kg ha−1. Late blight disease was controlled by 75% mancozeb wettable powder (Hebei Shuangji Co., Ltd., Shijiazhuang City, China) and 75% metalaxyl-mancozeb wettable powder (Zhejiang Heben Pesticide & Chemicals Co., Ltd., Wenzhou City, China) applied (1.5 kg ha−1) to the canopy on July 5 and August 5, 2013, respectively.

Response Variables

Tuber Yield and Components

The final harvest was conducted on September 13, 2013, with yields recorded from the centre two rows of the plot to avoid border effects. Marketable tuber (per tuber fresh weight > 150 g) yield (MTY) and total fresh tuber yield (FTY) were measured.

Irrigation WUE (WUEi, kg m−3) was calculated by dividing the total tuber dry biomass by the amount of water received by each treatment, including the contribution from rainfall, for open field conditions. Total tuber dry biomass was determined by FTY multiplied by tuber dry biomass of 100 g tuber fresh biomass (100 g sample of fresh tuber was taken from three representative tubers and then dried in an air forced oven at 75 °C (Kheirandish and Harighi 2015) until the weight was constant).

Environmental and Economic Indicators

Carbon footprint was calculated using the online model “Cool Farm Tool” developed by the University of Aberdeen and the Sustainable Food Lab (CFA 2013) and based on field information about yield, seed amount, planting and harvest date, soil texture, fertiliser amount, fungicide amount, above ground biomass, irrigation and pumping energy use and fuel for field management (see details in Haverkort and Hillier 2011). For the economic comparison, net benefit was calculated based on the costs including fixed assets and operation. The input-output ratio (total input costs/yield output) for all treatments was determined by the total input costs and yield output data. Depreciation of DI and PRD was different due to the irrigation system. The useful life of the irrigation system was based on the experience of the irrigation equipment company (Dayu Water-saving Group, Wuwei, China; see Table 2).

Data Analysis and Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA using a randomised block design. Dunnett’s multiple range test was applied to compare water restriction treatments against control (FI), then Duncan’s test was applied to all measured parameters in order to assess differences among irrigation treatments. All the statistical analyses were run with SPSS v20.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Yield Components and WUEi

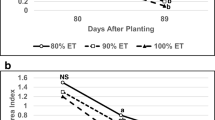

There were no significant differences (P > 0.05) among the treatments for MTY and FTY in shelter and open field conditions (Table 3). In general, FTY and MTY in open field condition (38.1 and 25.7 Mg ha−1, respectively) were 21.8 and 7.0% higher than shelter condition (31.3 and 24.0 Mg ha−1, respectively) (Fig. 3). Under both conditions, the higher FTY and MTY were obtained by E-PRD50 and E-DI50 and the lower FTY and MTY were obtained by L-PRD50 and L-DI50 (Fig. 3). Similar to yield components, there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) among treatments in WUEi for open field conditions whereas in shelter conditions this trait showed significantly (P < 0.01) higher values under late treatments (5.6 kg m−3 on average) and lower values for the control (FI, 2.8 ± 0.3 kg m−3) (Table 3, Fig. 3). In general, WUEi in open field conditions (2.6 kg m−3) was 45.9% lower than under shelter conditions (4.8 kg m−3) (Fig. 3). Due to the water contribution from rainfall (253.1 mm), the irrigation in open field conditions required 78.3% less irrigation water than in shelter conditions in FI (Table 4).

Economic Benefit Analysis

Under shelter conditions, the net benefit for FI was 19,246 RMB ha−1 (as a reference for the reader, 1 RMB = 6.5 US$), which was the highest followed by E-DI50 > L-PRD50 > E-PRD50 > L-DI50 (Table 5). Although the cost of DI was 10.6 and 16.3% higher than FI and PRD, respectively, the net benefit of E-DI50 was relatively high (18,379 RMB ha−1) i.e. only 4.5% less than FI (Table 5). In open field conditions, E-PRD50 produced the highest net benefit (24,743 RMB ha−1) followed by L-PRD50 > L-DI50 > FI > E-DI50, but the amplitudes of the net benefits among all the treatments were smaller than those under shelter conditions (Table 5). The average value showed that the irrigation system cost for DI was 4.8 times higher than for PRD and FI, where extra costs were mainly associated with pipelines and filter systems (Table 2), machinery and laying and drip line collection (Table 5). The yield output was higher in FI (35,516 RMB ha−1) than DI followed by PRD (35,304 and 33,722 RMB ha−1, respectively, Table 5). The other costs including seed, chemicals and fertilisers were the same for all the treatments whereas the net benefits for PRD and DI were only reduced by 5.3 and 0.6%, respectively, compared with FI (Table 5). PRD produced 3.1% higher net benefit than DI through low costs for irrigation system and machinery. The input-output ratios for FI and PRD (0.4) were 10% lower than DI (Table 5).

Carbon Footprint as an Environmental Indicator

CO2 emissions from fertiliser and soil/fungicides were the same for both treatments, but CO2 emissions from the energy use of DI were 19% higher than that of PRD as well as from crop residue and seed production (Table 6). In general, the total CO2 emission of PRD was 3659 kg ha−1 (109 kg CO2 Mg fresh potato−1) which was 14% lower than DI through less crop residue (above ground biomass) and energy use (lay and collect pipe line) (Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, both PRD and DI were irrigated with the same amount of water which was 50% of the water used in FI. In spite of the sizable reduction in irrigated water, tuber yields did not differ from the control (FI). This finding was in agreement with that of other studies (Foti et al. 1995; Erdem et al. 2005; Yactayo et al. 2013, 2017) showing the usefulness of both methods to save water in potato cultivation. The results confirmed the hypothesis that PRD produced no significant difference in tuber yield and WUEi compared to DI, but in an economically and environmentally friendly manner, under both tested conditions.

PRD and Drip Irrigation Did Not Penalise Tuber Yield and Improved WUEi

In both conditions, fresh tuber yield for all the treatments did not show significant differences. In the open field, the response was hindered by the supplementary water from rainfall which offset the benefit of FI. However, under the shelter, the advantages of the PRD and DI treatments were evident in that FTY and MTY were not significantly decreased compared with FI. PRD irrigation can positively affect the soil temperature and water uptake, consequently preventing significant tuber yield reduction (Karandish and Shahnazari 2016). Our results were in agreement with studies testing alternate deficit irrigation or PRD (Wang et al. 2009; Xie et al. 2012; Yactayo et al. 2013, 2017; Abdelraouf 2016) and deficit irrigation (Erdem et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2009) in which potato yield was not significantly reduced using 50% of the water supplied in FI. No significant (P > 0.05) reductions in potato tuber yield have been reported in studies comparing furrow versus drip irrigation when the latter used the same criteria as the former (Erdem et al. 2005, 2006; Kumar et al. 2009; Ati et al. 2012). Similar to our results, Erdem et al. (2005) reported that DI at 50% of soil water demand showed similar tuber yield to FI irrigated at 100% of soil water demand. An increased soil moisture frequency and aeration effectiveness in the root zone, a reduction in nutrient leaching and percolation, an enhanced nutrient efficiency and evapotranspiration or water consumption reduction are attributed advantages of DI compared to FI in potato (Erdem et al. 2006; Kumar et al. 2009) and other Solanaceous crops (Tagar et al. 2012). However, we could not find studies in the literature comparing alternate deficit irrigation or PRD versus DI in potato or other crops using 50% of water amount of FI. Nevertheless, when these two irrigation techniques were compared in other crops, PRD produced higher yields (similar to control) than DI, probably associated with differences in water volumes used per method (Sezen et al. 2014). The absence of significant differences (P > 0.05) in tuber yield found in the present work between PRD and DI requires future study to understand the physiological mechanisms and strategies in this crop under these two irrigation conditions (see for example Kachwaya et al. 2016).

WUEi under shelter conditions (range 2.8–5.6 kg m−3) was higher than that in open field conditions (range 2.2–2.7 kg m−3), and previously reported values in potato (0.6–2.6 kg m−3; Monneveux et al. 2013), thus showing the water-saving potentiality of PRD and DI. In this study, FI produced the lowest WUEi under both conditions compared with PRD and DI, which coincides with findings of other studies in potato (Erdem et al. 2006; Shahnazari et al. 2007; Kumar et al. 2009; Ati et al. 2012). Ahmadi et al. (2010) also reported similar results but depending on soil type, i.e. lower water productivity in FI under sandy loam and coarse sand conditions but not in loamy sand conditions. In general, as the water amount decreased, WUEi increased, which was in agreement with the results reported by Ahmadi et al. (2014) and de Lima et al. (2015) in potato. Notwithstanding, WUEi response depends on cultivars, soil texture, root distribution, weather condition and water amount (Ahmadi et al. 2010; Xie et al. 2012; Ahmadi et al. 2014; El-Abedin et al. 2017). For example, there were other studies which reported lower WUEi under PRD furrow irrigation (Ahmadi et al. 2014) and PRD drip irrigation treatments (El-Abedin et al. 2017) compared to FI. El-Abedin et al. (2017) also reported that potato under deficit drip irrigation with 50–70% of the water supplied for drip full irrigation resulted in similar WUEi compared to FI.

The results of this study showed that irrigation treatments initiated 2 weeks after TIO for both DI and PRD, with only 36% of the total water amount applied to FI, did not significantly reduce yield, which was in agreement with other studies in potato (Jovanovic et al. 2010; Xie et al. 2012; Yactayo et al. 2017). The findings showed that both water restriction timing and water amount must be considered when water-saving technologies are implemented in potato. Late treatments, starting 2 weeks after TIO, produced higher WUEi without significant tuber yield reduction. Since this stage is considered the most water-sensitive stage (van Loon 1981), exposing the plant to drought stress in the early growth period causes a priming effect after which plants are more prepared to tolerate the next water restrictions events. Short-term water stress memory improvement after PRD treatments has been reported in potato (Xu et al. 2011; Yactayo et al. 2013) and this study supports these findings, but further research is required to understand the underlying mechanisms (epigenetic effects, protein signalling).

PRD Showed Economic Benefits and Lower Carbon Footprint than Drip Irrigation

Although the average yield output of DI was 4.7% higher than PRD, the costs of the former were 16.3 and 10.6% higher than PRD and FI, respectively, caused by filter systems, pipe lines and their management, including laying, maintenance and cleanup (Table 5). This result was in agreement with economic comparisons in potato (Kumar et al. 2009) and other crops like cotton and wheat where the DI costs were reported to be 8.3 and 36% higher than FI, respectively, with similar yield output in both irrigation systems (Huang 2005; Li 2012). However, while in cabbage, tomato, cucumber, eggplant and pepper the costs of FI were 4% higher than DI, this was attributed to the fact that the calculations did not include the head and pipeline used in the DI system (Zheng et al. 2010). Also, in this study, FI generated the highest net benefit followed by PRD and DI, which was partly in accordance with the result in pepper where the net benefit of DI from the output was reduced mainly due to the higher cost of the irrigation system (Sezen et al. 2015). Furthermore, PRD was a more environmentally friendly technology producing a total average CO2 emission of 109 kg CO2 Mg fresh potato−1, which was 10% lower than that emitted by DI (Table 6). The CO2 emission values reported in this study (109–121 kg CO2 Mg fresh potato−1) were in the range (71–310 kg CO2 Mg fresh potato−1) of others reported in potato cropping systems (Röös et al. 2010; van Evert et al. 2013; Haverkort et al. 2014; Steyn et al. 2016). However, as the fertilisers were only applied once before planting, the most important contributors (energy and crop residual) of CO2 emissions in this study were different to the most important factor (fertiliser-induced emissions) in the aforementioned works.

Conclusion

The application of water-saving irrigation technologies like partial root-zone drying (PRD) or drip irrigation (DI), starting 2 weeks after tuber initiation onset (TIO), can save 50% of the water used per irrigation in common irrigation practices like furrow irrigation (FI), thus avoiding significant tuber yield reduction while raising irrigation water use efficiency (WUEi). PRD maintained yield, improved WUEi, saved 2198 RMB ha−1 and reduced 12 kg CO2 Mg fresh potato−1 of carbon emissions, compared to DI. However, more studies are necessary to test these preliminary findings in other environments with commonly used water stress tolerant potato cultivars, especially in the semi-arid regions of China. Such studies would nurture the scaling-up of irrigation methods like PRD which appears to be of lower cost and more environmentally friendly than DI. To further this scaling-up process, the involvement of local farmers and governmental efforts are required to achieve success in the adoption of this technology. The potential revenues in terms of reducing the pressure on the limited water resources available, fully justify such an undertaking.

References

Abdelraouf RE (2016) Effect of partial root zone drying and deficit irrigation techniques for saving water and improving productivity of potato. Int J ChemTech Res 9(8):170–177

Ahmadi SH, Andersen MN, Plauborg F, Poulsen RT, Jensen CR, Sepaskhah AR, Hansen S (2010) Effects of irrigation strategies and soils on field grown potatoes: yield and water productivity. Agric Water Manag 97:1923–1930

Ahmadi SH, Agharezaee MN, Kamgar-Haghighi AA, Sepaskhah AR (2014) Effects of dynamic and static deficit and partial root zone drying irrigation strategies on yield, tuber sizes distribution, and water productivity of two field grown potato cultivars. Agric Water Manag 134:126–136

Ati AS, Iyada AD, Najim SM (2012) Water use efficiency of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) under different irrigation methods and potassium fertilizer rates. Ann Agric Sci 57(2):99–103

Chen W, Du WL (2011) Application of drip irrigation in potato cultivation. J Agric Mechanization Res 33(7):247–252

CHNMOA (2015) News. http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/mls/mlshydt/201501/t20150107_4325191.htm

Cool Farm Alliance (2013) Sign in. https://app.coolfarmtool.org/account/login/

de Lima RSN, de Assis Figueiredo FAMM, Martins AO, de Deus BC d S, Ferraz TM, Gomes M d M d A, de Sousa EF, Glenn DM, Campostrini E (2015) Partial root zone drying (PRD) and regulated deficit irrigation (RDI) effects on stomatal conductance, growth, photosynthetic capacity, and water-use efficiency of papaya. Sci Hortic 183:13–22

Deng LS, Lin CL, Tu PF, Gong L, Zeng E, Zhang CL (2009) Application of drip-fertigation to potato production. Chinese Potato J 23(6):321–324

El-Abedin TKZ, Mattar MA, Alazba AA, Al-Ghobari HM (2017) Comparative effects of two water-saving irrigation techniques on soil water status, yield, and water use efficiency in potato. Sci Hortic 225:525–532

Erdem T, Orta AH, Erdem Y, Okursoy H (2005) Crop water stress index for potato under furrow and drip irrigation systems. Potato Res 48(1–2):49–58

Erdem T, Erdem Y, Orta H, Okursoy H (2006) Water-yield relationships of potato under different irrigation methods and regimens relação água-produção na cultura da batata sob diferentes métodos e regimes de irrigação. Sci Agric 63(3):226–231

FAO (2018) FAOSTAT, statistics database, agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome

Foti S, Mauromicale G, Ierna A (1995) Influence of irrigation regimes on growth and yield of potato cv. Spunta. Potato Res 38:307–318

Giuliani MM, Gatta G, Nardella E, Tarantino E (2016) Water saving strategies assessment on processing tomato cultivated in Mediterranean region. Ital J Agron 11(1):69–76

Guo SL, Jiang HF, Wang SQ, Kang YH, Liu SP (2015) Schedule of underground drip irrigation for potato. Water Saving Irrig 8:11–14,19

Haverkort AJ, Hillier JG (2011) Cool farm tool—potato: model description and performance of four production systems. Potato Res 54(4):355–369

Haverkort AJ, Sandaña P, Kalazich J (2014) Yield gaps and ecological footprints of potato production systems in Chile. Potato Res 57(1):13–31

Huang SJ (2005) Comparative effects of traditional irrigation and drip irrigation on cotton economic benefit. Xinjiang State Farms Econ 8:87–90

Ibrahim MM, Elbaroudy AA, Taha AM (2016) Irrigation and fertigation scheduling under drip irrigation for maize crop in sandy soil. Int Agrophysics 30(1):47–55

Jovanovic Z, Stikic R, Vucelic-Radovic B, Paukovic M, Brocic Z, Matovic G, Rovcanin S, Mojevic M (2010) Partial root-zone drying increases WUE, N and antioxidant content in field potatoes. Eur J Agron 33(2):124–131

Kachwaya DS, Chandel JS, Vikas G, Khachi B (2016) Effect of drip and furrow irrigation on yield and physiological performance of strawberry (Fragaria×ananassa, Duch.) cv. Chandler. Indian J Plant Physiol 21(3):1–4

Kang SZ, Zhang JH, Liang ZS (1997) The controlled alternative irrigation, a new approach for water-saving regulation in farm land. Agric Res Arid Areas 15(1):1–6

Karandish F, Shahnazari A (2016) Soil temperature and maize nitrogen uptake improvement under partial root-zone drying irrigation. Pedosphere 26(6):872–886

Kheirandish Z, Harighi B (2015) Evaluation of bacterial antagonists of Ralstonia solanacearum, causal agent of bacterial wilt of potato. Biol Control 86(1):14–19

Kruzhilin IP, Doubenok NN, Ganiev MA, Melichov VV, Abdou NM, Rodin KA (2016) Combination of the natural and anthropogenically-controlled conditions for obtaining various rice yield using drip irrigation systems. Russ Agric Sci 42(6):454–457

Kumar S, Asrey R, Manual G, Singh R (2009) Microsprinkler, drip and furrow irrigation for potato (Solanum tuberosum) cultivation in a semi-arid environment. Indian J Agric Sci 79(3):165–169

Li ZG (2008) Effects of different treatments of irrigation and fertilization on yield and quality of cherry tomato. J Anhui Agric Sci 36(18):7623–7624,7936

Li ZG (2016) Effects of different treatments of irrigation and fertilization on yield and quality of cherry tomato. J Anhui Agric Sci 36(18):7623–7624

Li J (2012) Analysis of drip irrigation and traditional irrigation on wheat production. J Modern Agric 12:16–17

Liu FL, Shahnazari A, Andersen MN, Jacobsen SE, Jensen CR (2006a) Physiological responses of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) to partial root-zone drying: ABA signalling, leaf gas exchange, and water use efficiency. J Exp Bot 57(14):3727–3735

Liu FL, Shahnazari A, Andersen MN, Jacobsen SE, Jensen CR (2006b) Effects of deficit irrigation (DI) and partial root drying (PRD) on gas exchange, biomass partitioning, and water use efficiency in potato. Sci Hortic 109(2):113–117

Luo QY, Liu Y, Gao MJ, Yi XF (2015) Status quo and prospect of China’s potato industry. Agric Outlook 3:35–40

Monneveux P, Ramírez DA, Pino MT (2013) Drought tolerance in potato (S. tuberosum L.). Can we learn from drought tolerance research in cereals? Plant Sci 205-206:76–86

Perry C, Steduto P, Karajeh F (2017) Does improved irrigation technology save water? A review of the evidence, discussion paper on irrigation and sustainable water resources management in the Near East and North Africa. FAO, Cairo, Egypt

Qin JH, Meng ML, Zhou CY, Zhou CY, Li GN (2011) Effects of drip irrigation on yield of potato under mulching. Chinese Agric Sci Bull 27(18):204–208

Qin JH, Chen YJ, Zhou CY, Pang BP, Meng ML (2013) Effects of frequency of drip irrigation frequency under mulch on potato growth, yield and water use efficiency. Chinese J Eco-Agric 21(7):824–830

Röös E, Sundberg C, Hansson PA (2010) Uncertainties in the carbon footprint of food products: a case study on table potatoes. Int J Life Cycle Assess 15(5):478–488

Saeed H, Grove IG, Kettlewell PS, Hall NW (2008) Potential of partial root zone drying as an alternative irrigation technique for potatoes (Solanum tuberosum). Ann Appl Biol 152(1):71–80

Sezen SM, Yaza A, Daşgan Y, Yucel S, Akyildiz A, Tekin S et al (2014) Evaluation of crop water stress index (CWSI) for red pepper with drip and furrow irrigation under varying irrigation regimes. Agric Water Manag 143(9):59–70

Sezen SM, Yazar A, Haydar S, Baytorun N, Daşgan Y, Akyildiz A et al (2015) Comparison of drip- and furrow-irrigated red pepper yield, yield components, quality and net profit generation. Irrig Drain 64(4):546–556

Shahnazari A, Liu F, Andersen MN, Jacobsen SE, Jensen CR (2007) Effects of partial root-zone drying on yield, tuber size and water use efficiency in potato under field conditions. Field Crop Res 100(1):117–124

Shen B, Han HL, Liang ST (2011) Economic benefit analysis on off-season vegetable cultivation on Bashang cold upland region based on different irrigation methods. J Anhui Agric Sci 39(1):556–559

Stalham MA, Allen EJ, Rosenfeld AB, Herry FX (2007) Effects of soil compaction in potato (Solanum tuberosum) crops. J Agric Sci 145(4):295–312

Steyn JM, Franke AC, Waals JEVD, Haverkort AJ (2016) Resource use efficiencies as indicators of ecological sustainability in potato production: a South African case study. Field Crop Res 199:136–149

Tagar A, Chandio FA, Mari IA, Wagan B (2012) Comparative study of drip and furrow irrigation methods at farmer’s field in Umarkot. World Acad Sci Eng Technol 6(9):863–867

van Evert FK, de Ruijter FJ, Conijn JG, Rutgers B, Haverkort AJ (2013) Worldwide sustainability hotspots in potato cultivation. 2. Areas with improvement opportunities. Potato Res 56(4):355–368

van Loon CD (1981) The effect of water stress on potato growth, development, and yield. Am Potato Res 58(1):51–69

Wang FX, Kang YH, Liu SP, Hou XY (2007) Effects of soil matric potential on potato growth under drip irrigation in the North China plain. Agric Water Manag 88(1–3):34–42

Wang H, Liu FL, Andersen MN, Jensen CR (2009) Comparative effects of partial root-zone drying and deficit irrigation on nitrogen uptake in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.). Irrig Sci 27(6):443–448

Xie KY, Wang XX, Zhang RF, Gong XF, Zhang SB, Mares V, Gavilán C, Posadas A, Quiroz R (2012) Partial root-zone drying irrigation and water utilization efficiency by the potato crop in semi-arid regions in China. Sci Hortic 134:20–25

Xu HL, Qin FF, Xu QC, Tan JY, Liu GM (2011) Applications of xerophytophysiology in plant production—the potato crop improved by partial root zone drying of early season but not whole season. Sci Hortic 129(4):528–534

Xue DX, Zhang HJ, Ba YC, Zhang M, Wang SJ (2017) Effects of regulated deficit irrigation on soil environment and yield of potato under drip irrigation. Acta Agric Boreali-Sinica 03(32):229–238

Yactayo W, Ramírez DA, Gutiérrez R, Mares V, Posadas A, Quiroz R (2013) Effect of partial root-zone drying irrigation timing on potato tuber yield and water use efficiency. Agric Water Manag 123:65–70

Yactayo W, Ramírez DA, German T, Worku A, Abeb A, Harahagazwe D, Mares V, De Mendiburu F, Quiroz R (2017) Improving potato cultivation using siphons for partial root-zone drying irrigation: a case study in the Blue Nile river basin, Ethiopia. Open Agric 2(1):255–259

Yang CZ, Yaniger SI, Craig JV, Klein DJ, Bittner GD (2011) Most plastic products release estrogenic chemicals: a potential health problem that can be solved. Environ Health Perspect 119(7):989–996

Zhang D, Guo P (2016) Integrated agriculture water management optimization model for water saving potential analysis. Agric Water Manag 170(1):5–19

Zhao X, Wang HY (2016) Effect of different irrigating treatments on yield of potato. West China Develop 4:45–49

Zheng BG, Zhang YP, Kong DJ, Luo JL, Peng WD, Guo SH, Zhu JX (2010) Effects of three irrigation technologies on production efficiency and economic benefit of vegetables in greenhouse. Ningxia J Agric Forestry Sci Tech 6:3–4

Zhou F, Zhang ZM (2015) Comparison and analysis on effect of phosphorus nutrition on drought-resistance of potatoes of the Kexin 1 and Shepody. J Shandong Agric Univ (Nat Sci Ed) 46(1):43–46

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Jiang Yin and Prof. Yan Feng in Hebei North College for their logistical support including seed, fertiliser and labour hiring and Dr. Dongsheng Yang in Shenzhen Noposion Agrochemicals Co., Ltd., for his field management support. This study is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Xie Kaiyun, the driving force behind this undertaking and co-author of this work, who suddenly passed away during the revision of this paper.

Funding

We would like to thank the CGIAR Research Programs on Water, Land and Ecosystems and Root Tubers and Banana and the CGIAR Fund donors for funding this research. For a list of CGIAR Fund donors, please see: http://www.cgiar.org/whowe-are/cgiar-fund/fund-donors-2/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

Kaiyun Xie passed away on May 3, 2018

- Kaiyun Xie

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, J., Ramírez, D.A., Xie, K. et al. Is Partial Root-Zone Drying More Appropriate than Drip Irrigation to Save Water in China? A Preliminary Comparative Analysis for Potato Cultivation. Potato Res. 61, 391–406 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-018-9393-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-018-9393-0