Abstract

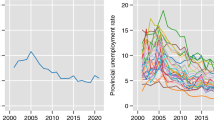

Differences in regional unemployment rates, as well as their formation mechanism and persistence, have given rise to many papers in recent decades. The present work contributes to this strand of literature from two different perspectives. In the first part of our work, we follow the methodological proposal put forward by Hofler and Murphy (1989) and Aysun et al. (2014). We use a stochastic cost frontier to break down actual Spanish provincial unemployment (NUTS-3) into two different estimation components: the first associated with aggregate supply side factors, and the other more related to aggregate demand side factors. The second part of our research analyses the existence of spatial dependence patterns among Spanish provinces in actual unemployment and in the two above-mentioned components. The decomposition carried out in the first part of our research tells us what margin policymakers have when dealing with unemployment reductions by means of aggregate supply and aggregate demand policies. Finally, spatial analysis of unemployment rates in Spanish provinces may also have significant implications from the standpoint of economic policy since we find common formation patterns or clusters of unemployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This methodology is applied to a database which provides information on the 50 Spanish provinces for the period between 1984 and 2012. The 50 Spanish provinces correspond to the third level (NUTS-3) of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for statistics. For further information concerning the concept of NUTS, see: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/overview.

The work of Fabiani and Mestre (2000) sets out some of these techniques applied to the case of the European Union.

It is precisely this use of information concerning vacancies which makes it impossible for the present paper to adopt the technique used by Warren (1991). It is well known that information concerning vacancies in Spain is extremely poor.

Even in textbooks like Krugman et al. (2011), this classification can be found.

The same happens with the frictional component (\( {U}_{it}^F \)).

These imbalances arise as a result of a certain amount of institutional rigidity, linked to the downward rigidity of wages (minimum wage, collective bargaining, etc.) or employment protection, amongst others. Other factors which also impact strongly on the imbalances between supply and demand are: inflow and outflow in the labour market, labour force skills, low labour productivity, the industry composition of employment or the demographic structure of the population, to name but a few (Jackman and Roper 1987; Blanchard and Jimeno 1995; Blanchard 2017).

Rogerson (1997) provides a number of explanations, definitions and nomenclature of the concept.

Even when macroeconomic conditions reach optimal levels and there are no problems of insufficient aggregate demand.

Due, for example, to a fall in consumer or business confidence. A contractive monetary policy or a cut in public spending might explain the existence of insufficient aggregate demand.

Elhorst (2003) refers to commuting as one of the factors to be taken into account when explaining regional unemployment rates.

The growing cost as distance increases not only concerns purely monetary costs (transport costs, accommodation costs) but also costs associated to other factors (family, friends etc.).

There might be adjacent areas which display determinant economic features that function poorly. Here, the “spillover” which occurs in adjacent areas proves relatively inefficient from the economic standpoint, generating a negative Spillover Effect. For example, large-scale redundancies in a given area might trigger depressive economic effects in adjacent areas. See Martin (1997).

For example, increasing public spending on infrastructures in area “i” gives rise to a reduction in unemployment both in area “i” and adjacent area “j”, leading to the unemployment rates being similar in the two areas. In the case of a negative aggregate demand shock (for example, a cut in public spending), the opposite would occur. In other words, there would be an increase in unemployment in the two neighbouring areas.

The lack of information which is sufficiently ample and comparable over time concerning existing vacancies in the labour market makes it extremely difficult to extract the frictional component (\( {U}_{it}^F \)) in line with the approach adopted in Warren (1991), Bodman (1999) and Aysun et al. (2014), such that said component is estimated together with structural unemployment.

In this case, several distributions have been proposed in the econometric literature: Normal truncated (Stevenson, 1980), Semi-Normal (Aigner et al., 1977), Exponential (Meeusen and van Den Broeck, 1977) and Gamma (Greene, 1990).

This dichotomous variable is introduced due to the fact that in 2001 a methodological change was implemented which affected how unemployment was measured. These methodological changes may be seen in http://www.ine.es/epa02/meto2002.htm.

For a more detailed explanation of this kind of statistics, see Moreno and Vayá (2002).

Ceuta and Melilla have been excluded from the analysis due to their scant representativeness together with the scarce availability of some of the data used.

The inverse situation can be found in the work of Galiani et al. (2005). In this research, the authors show that the persistence of unemployment in the regions of Argentina is very low compared to the situation in Spain or the UK.

In Summers et al. (1986) a more detailed explanation of the phenomenon may be found.

Maguire et al. (2013) provides a thorough explanation of this phenomenon.

See Eichhorst and Neder (2014) for a broader explanation of the problems related to the “school-work” transition in certain European Mediterranean countries.

See López-Bazo and Motellón (2012) for a more comprehensive explanation of regional differences in the matter of human capital, its impact on the labour market and on wages.

For a more detailed definition of educational variables, see http://www.ivie.es/downloads/caphum/series-2013/metodologia-series-capital-humano-1964-2013.pdf

For a more detailed definition about the construction of net capital stock, see http://web2016.ivie.es/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Metodolog%C3%ADa_basedatos_stockcapital_ED.pdf

For a more detailed explanation about services in the retailing industry (SRIit) and services in the non-retailing industry (SNRIit), see http://web2011.ivie.es/downloads/caphum/series-2013/metodologia-series-capital-humano-1964-2013.pdf

As regards the impact of temporary employment, we searched for data with provincial disaggregation but failed to find a database covering our whole period. Therefore, we built the percentage of temporary employment over total employment for each NUTS2 spatial unit (autonomous community) in Spain, and applied these figures to each province (NUTS3 spatial unit) depending on the autonomous community to which it belongs. Given the lack of adequate data, we have also been forced to carry out the empirical work for the period from 1991 to 2012).

The test of maximum likelihood rejects the notion that variance of the disturbance measuring inefficiency is zero.

A good example for the case of Spain might be certain jobs in the tourism industry.

Using a panel including 21 OECD countries, Oesch (2010) provides empirical evidence concerning which variables most impact on unemployment among low-skilled workers.

The previous result is maintained when we use the percentage of employed persons with secondary education and the percentage of employed persons with tertiary education in each province, rather than the share of the active population with secondary education (SEit) and the share of the active population with tertiary education (TEit).

Some negative values have been obtained when estimating the natural rate of unemployment for certain provinces. Despite this, said values account for only a very small part compared to the total number of estimations, and in all cases are below 2% of the total number of estimations obtained.

Estimations were performed based on the basic specification. Tests were carried out using the rest of the specifications and the results are very similar. These results are available from the authors upon request.

Detailed results are available upon request from the authors.

Estimations of cyclical unemployment have also been conducted using the basic specification. Tests were carried out using the rest of the specifications with the results being very similar. These results are available from the authors upon request.

Detailed results are available upon request from the authors.

See Jimeno and Santos (2014) for a more comprehensive explanation about the effects of this period in the case of Spain.

This type of spatial matrix is also used in Basile et al. (2009).

This type of spatial matrix is also used in Akçagün (2017).

The diagrams obtained for the remaining spatial matrices also point to the existence of spatial dependence for the actual unemployment rate in a way similar to that observed in the five nearest neighbours’ matrix. Detailed results are available upon request from the authors.

As noted in the previous case, the remaining spatial matrices also point to the existence of spatial dependence regarding the natural rate of unemployment.

Again, the diagrams obtained with different spatial matrices seem to indicate the existence of spatial dependence for the cyclical rate of unemployment (except for the administrative matrix).

The results shown have been obtained using the Knn = 5 matrix. Nevertheless, tests have been carried out using the remaining spatial matrices and the conclusions are similar. The results of these tests are available upon request from the authors. Tests were also conducted after removing the islands. The values of the statistics did not alter substantially.

Cracolici et al. (2007) define the notion of spatial persistence based on the situation which leads “adjacent provinces to display unemployment rates that are similar over a spatial area and at different periods”.

Elhorst (2003) cites some works which have explored the effect of collective bargaining on unemployment. Most report a positive effect, which would seem to confirm the previously posited hypothesis.

Cazes et al. (2013) show how in Spain, during the Great Recession, labour market adjustment mainly occurred through the external margin of adjustment (layoffs and downsizing) in the labour market.

See Elhorst (2014) for a more complete explanation about the Spatial Durbin Model.

References

Aigner, D., Lovell, C. K., & Schmidt, P. (1977). Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. Journal of Econometrics, 6(1), 21–37.

Akçagün, P. (2017). Provincial growth in Turkey: A spatial econometric analysis. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 10(2), 271–299.

Anselin, L. (1995). Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geographical Analysis, 27(2), 93–115.

Aysun, U., Bouvet, F., & Hofler, R. (2014). An alternative measure of structural unemployment. Economic Modelling, 38, 592–603.

Azmat, G., Güell, M., & Manning, A. (2006). Gender gaps in unemployment rates in OECD countries. Journal of Labor Economics, 24(1), 1–37.

Azorín, J. D. B. (2013). La distribución del desempleo en las provincias españolas: Un análisis con datos de panel mediante el filtrado espacial. Investigaciones Regionales: Journal of Regional Research, 27, 143–154.

Bande, R., & Karanassou, M. (2013). The natural rate of unemployment hypothesis and the evolution of regional disparities in Spanish unemployment. Urban Studies, 50(10), 2044–2062.

Bande, R., & Karanassou, M. (2014). Spanish regional unemployment revisited: The role of capital accumulation. Regional Studies, 48(11), 1863–1883.

Bande, R., Fernández, M., & Montuenga, V. (2008). Regional unemployment in Spain: Disparities, business cycle and wage setting. Labour Economics, 15(5), 885–914.

Bande, R., Fernández, M., Montuenga, V., & Sanromá, E. (2012). Wage flexibility and local labour markets: A test on the homogeneity of the wage curve in Spain. Investigaciones Regionales, 24, 175–198.

Basile, R, Girardi, A., Mantuano, M. (2009). Regional unemployment traps in Italy: Assessing the evidence. Retrieved September 28.

Battese, G. E., & Coelli, T. J. (1995). A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empirical Economics, 20(2), 325–332.

Baxter, M., & King, R. G. (1999). Measuring business cycles: Approximate band-pass filters for economic time series. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(4), 575–593.

Bentolila, S., & Jimeno, J.F. (2003). Spanish unemployment: The end of the wild ride?. FEDEA working paper 2003–10, FEDEA, Fundación de Estudios de Economía Aplicada, Madrid.

Bentolila, S., Dolado, J. J., & Jimeno, J. F. (2012). Reforming an insider-outsider labor market: The Spanish experience. IZA Journal of European Labor Studies, 1(1), 1–29.

Bertola, G., Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2007). Labor market institutions and demographic employment patterns. Journal of Population Economics, 20(4), 833–867.

Blanchard, O.J. (2017). Macroeconomics (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Blanchard, O. J., & Jimeno, J. F. (1995). Structural unemployment: Spain versus Portugal. The American Economic Review, 85(2), 212–218.

Blanchard, O. J., & Katz, L. (1992). Regional evolutions. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (1), 1–75.

Blanchard, O. J., Jaumotte, F., & Loungani, P. (2014). Labor market policies and IMF advice in advanced economies during the great recession. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 3(1), 1–23.

Bodman, P. M. (1999). Labour market inefficiency and frictional unemployment in Australia and its states: A stochastic frontier approach. The Economic Record, 75(2), 138–148.

Booth, A. L., Francesconi, M., & Frank, J. (2002). Temporary jobs: Stepping stones or dead ends? The Economic Journal, 112(480), 189–213.

Bramoullé, Y., & Saint-Paul, G. (2010). Social networks and labor market transitions. Labour Economics, 17(1), 188–195.

Brueckner, J. K. (2003). Strategic interaction among governments: An overview of empirical studies. International Regional Science Review, 26(2), 175–188.

Calvo-Armengol, A., & Jackson, M. O. (2004). The effects of social networks on employment and inequality. The American Economic Review, 94(3), 426–454.

Cazes, S., Verick, S., & Al Hussami, F. (2013). Why did unemployment respond so differently to the global financial crisis across countries? Insights from Okun’s law. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 2(1), 1–18.

Cingano, F., & Rosolia, A. (2012). People I know: Job search and social networks. Journal of Labor Economics, 30(2), 291–332.

Clark, A. E. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(2), 323–351.

Cliff, A.D., & Ord, J.K. (1981). Spatial processes: Models & applications. Taylor & Francis.

Conley, T. G., & Topa, G. (2002). Socio-economic distance and spatial patterns in unemployment. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 17(4), 303–327.

Costa, H., Veiga, L. G., & Portela, M. (2015). Interactions in local governments spending decisions: Evidence from Portugal. Regional Studies, 49(9), 1441–1456.

Cracolici, M. F., Cuffaro, M., & Nijkamp, P. (2007). Geographical distribution of unemployment: An analysis of provincial differences in Italy. Growth and Change, 38(4), 649–670.

del Barrio-Castro, T., López-Bazo, E., & Serrano-Domingo, G. (2002). New evidence on international R&D spillovers, human capital and productivity in the OECD. Economics Letters, 77(1), 41–45.

Dietz, R. D. (2002). The estimation of neighborhood effects in the social sciences: An interdisciplinary approach. Social Science Research, 31(4), 539–575.

Dolado, J.J., Felgueroso, F., Jimeno, J.F. (1999). The causes of youth labour market problems in Spain: Crowding-out, institutions, or the technology shifts?. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Departamento de Economía.

Dolado, J. J., Felgueroso, F., & Jimeno, J. F. (2000). Youth labour markets in Spain: Education, training, and crowding-out. European Economic Review, 44(4), 943–956.

Dolado, J. J., García-Serrano, C., & Jimeno, J. F. (2002). Drawing lessons from the boom of temporary jobs in Spain. The Economic Journal, 112(480), 270–295.

Eichhorst, W., & Neder, F. (2014). Youth unemployment in Mediterranean countries. No. 80, IZA Policy Paper.

Elhorst, J. P. (2003). The mystery of regional unemployment differentials: Theoretical and empirical explanations. Journal of Economic Surveys, 17(5), 709–748.

Elhorst, J. P. (2014). Spatial panel data models. In J. P. Elhorst (Ed.), Spatial econometrics (pp. 37–93). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

Fabiani, S., & Mestre, R. (2000). Alternative measures of the NAIRU in the euro area: Estimates and assessment. No. 17, ECB Working Paper.

Filiztekin, A. (2009). Regional unemployment in Turkey. Papers in Regional Science, 88(4), 863–878.

Galiani, S., Lamarche, C., Porto, A., & Sosa-Escudero, W. (2005). Persistence and regional disparities in unemployment (Argentina 1980–1997). Regional Science and Urban Economics, 35(4), 375–394.

García-Mainar, I., & Montuenga, V. (2003). The Spanish wage curve: 1994–1996. Regional Studies, 37(9), 929–945.

Grant, A. P. (2002). Time-varying estimates of the natural rate of unemployment: A revisitation of Okun’s law. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 42(1), 95–113.

Greene, W. H. (1990). A gamma-distributed stochastic frontier model. Journal of Econometrics, 46(1–2), 141–163.

Greene, W.H. (2008). The econometric approach to efficiency analysis. In: H.O. Fried, C.K. Lovell, S.S. Schmidt (Eds.), The measurement of productive efficiency and productivity growth (pp. 92–250). Oxford Scholarship Online.

Halleck-Vega, S. H., & Elhorst, J. P. (2016). A regional unemployment model simultaneously accounting for serial dynamics, spatial dependence and common factors. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 60, 85–95.

Hedström, P., Kolm, A.S., Aberg, Y. (2003). Social interactions and unemployment. Working paper. 2003:15, Institute Labor Market Policy Evaluation, Uppsala.

Hodrick, R. J., & Prescott, E. C. (1997). Postwar US business cycles: An empirical investigation. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 29(1), 1–16.

Hofler, R. A., & Murphy, K. J. (1989). Using a composed error model to estimate the frictional and excess-supply components of unemployment. Journal of Regional Science, 29(2), 213–228.

Huertas, I. P. M., Hernández, F. N., & Ibáñez, C. U. (2006). Persistencia del desempleo regional: El caso del sur de España. Revista de Economía Laboral, 3(1), 46–57.

Ioannides, Y. M., & Datcher Loury, L. (2004). Job information networks, neighborhood effects, and inequality. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(4), 1056–1093.

Jackman, R., & Roper, S. (1987). Structural unemployment. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 49(1), 9–36.

Jimeno, J. F., & Bentolila, S. (1998). Regional unemployment persistence (Spain, 1976–1994). Labour Economics, 5(1), 25–51.

Jimeno, J. F., & Santos, T. (2014). The crisis of the Spanish economy. SERIEs, 5(2–3), 125–141.

Johnson, J. A., & Kneebone, R. D. (1991). Deriving natural rates of unemployment for sub-national regions: The case of Canadian provinces. Applied Economics, 23(8), 1305–1314.

Jondrow, J., Lovell, C. K., Materov, I. S., & Schmidt, P. (1982). On the estimation of technical inefficiency in the stochastic frontier production function model. Journal of Econometrics, 19(2–3), 233–238.

Kahn, L. M. (2010). Employment protection reforms, employment and the incidence of temporary jobs in Europe: 1996–2001. Labour Economics, 17(1), 1–15.

Kondo, K. (2015). Spatial persistence of Japanese unemployment rates. Japan and the World Economy, 36, 113–122.

Krugman, P., Wells, R., Graddy, M. (2011). Essentials of economics. Worth Publishers.

Kumbhakar, S.C., & Lovell, C.K. (2003). Stochastic frontier analysis. Cambridge university press.

Lázaro, N., Moltó, M., & Sánchez, R. (2000). Unemployment determinants for women in Spain. Labour, 14(1), 53–77.

Lippman, S. A., & McCall, J. J. (1976a). The economics of job search: A survey: Part I. Economic Inquiry, 14(2), 155–189.

Lippman, S. A., & McCall, J. J. (1976b). The economics of job search: A survey: Part II. Economic Inquiry, 14(2), 347–368.

López, F. A., Martínez-Ortiz, P. J., & Cegarra-Navarro, J. G. (2017). Spatial spillovers in public expenditure on a municipal level in Spain. The Annals of Regional Science, 58(1), 39–65.

López-Bazo, E., & Motellón, E. (2012). Human capital and regional wage gaps. Regional Studies, 46(10), 1347–1365.

López-Bazo, E., & Motellón, E. (2013). The regional distribution of unemployment: What do micro-data tell us? Papers in Regional Science, 92(2), 383–405.

López-Bazo, E., Barrio, T. D., & Artis, M. (2002). The regional distribution of Spanish unemployment: A spatial analysis. Papers in Regional Science, 81(3), 365–389.

López-Bazo, E., Barrio, T. D., & Artís, M. (2005). Geographical distribution of unemployment in Spain. Regional Studies, 39(3), 305–318.

Maguire, S., Cockx, B., Dolado, J. J., Felgueroso, F., Jansen, M., Styczyńska, I., Kelly, E., McGuinness, S., Eichhorst, W., Hinte, H., & Rinne, U. (2013). Youth unemployment. Intereconomics, 48(4), 196–235.

Marston, S. T. (1985). Two views of the geographic distribution of unemployment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 100(1), 57–79.

Martin, R. (1997). Regional unemployment disparities and their dynamics. Regional Studies, 31(3), 237–252.

Maza, A., & Moral-Arce, I. (2006). An analysis of wage flexibility: Evidence from the Spanish regions. The Annals of Regional Science, 40(3), 621–637.

Maza, A., & Villaverde, J. (2009). Provincial wages in Spain: Convergence and flexibility. Urban Studies, 46(9), 1969–1993.

McCall, J. J. (1970). Economics of information and job search. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(1), 113–126.

Meeusen, W., & van Den Broeck, J. (1977). Efficiency estimation from cobb-Douglas production functions with composed error. International Economic Review, 18(2), 435–444.

Moran, P. A. (1948). The interpretation of statistical maps. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B: Methodological, 10(2), 243–251.

Moran, P. A. (1950). Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika, 37(1–2), 17–23.

Moreno, R., & Vayá, E. (2002). Econometría espacial. Nuevas técnicas para el análisis regional. Una aplicación a las regiones europeas. Investigaciones Regionales, 1, 83–106.

Moreno, R., Paci, R., & Usai, S. (2005). Spatial spillovers and innovation activity in European regions. Environment and Planning A, 37(10), 1793–1812.

Mortensen, D. T. (1970). Job search, the duration of unemployment and the Phillips curve. The American Economic Review, 60(5), 847–862.

Mortensen, D. T. (1986). Job search and labor market analysis. Handbook of Labor Economics, 2, 849–919.

Mortensen, D. T., & Pissarides, C. A. (1999). New developments in models of search in the labor market. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 2567–2627.

Murphy, K. J., & Payne, J. E. (2003). Explaining change in the natural rate of unemployment: A regional approach. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 43(2), 345–368.

Nickell, S., & Bell, B. (1996). Changes in the distribution of wages and unemployment in OECD countries. The American Economic Review, 86(2), 302–308.

Oesch, D. (2010). What explains high unemployment among low-skilled workers? Evidence from 21 OECD countries. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 16(1), 39–55.

Overman, H. G., & Puga, D. (2002). Unemployment clusters across Europe's regions and countries. Economic Policy, 17(34), 115–148.

Patacchini, E., & Zenou, Y. (2007). Spatial dependence in local unemployment rates. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(2), 169–191.

Posada, D. G., Morollón, F. R., & Viñuela, A. (2017). The determinants of local employment growth in Spain. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 1–23.

Rogerson, R. (1997). Theory ahead of language in the economics of unemployment. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(1), 73–92.

Romero-Ávila, D., & Usabiaga, C. (2008). On the persistence of Spanish unemployment rates. Empirical Economics, 35(1), 77–99.

Sala, H., & Trivín, P. (2014). Labour market dynamics in Spanish regions: Evaluating asymmetries in troublesome times. SERIEs, 5(2–3), 197–221.

Simón, H. J., Ramos, R., & Sanroma, E. (2006). Collective bargaining and regional wage differences in Spain: An empirical analysis. Applied Economics, 38(15), 1749–1760.

Solé-Ollé, A. S. (2003). Electoral accountability and tax mimicking: The effects of electoral margins, coalition government, and ideology. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(4), 685–713.

Stevenson, R. E. (1980). Likelihood functions for generalized stochastic frontier estimation. Journal of Econometrics, 13(1), 57–66.

Summers, L. H., Abraham, K. G., & Wachter, M. L. (1986). Why is the unemployment rate so very high near full employment? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1986(2), 339–396.

Tassinopoulos, A., & Werner, H. (1999). To move or not to move: Migration in the European Union (IAB labour market research topics 35). Neurenberg: IAB.

Tatsiramos, K., & van Ours, J. C. (2014). Labor market effects of unemployment insurance design. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28(2), 284–311.

Tobin, J. (1997). Supply constraints on employment and output: NAIRU versus natural rate. Cowles Foundation paper no. 1150.

Topa, G. (2001). Social interactions, local spillovers and unemployment. The Review of Economic Studies, 68(2), 261–295.

Topa, G., & Zenou, Y. (2015). Neighborhood and network effects. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, 5, 561–624.

Warren Jr., R. S. (1991). The estimation of frictional unemployment: A stochastic frontier approach. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 73(2), 373–377.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Roberto Bande, Hector Sala, and Enrique López-Bazo as well as to participants at the XLII Reunión de Estudios Regionales, the XII Jornadas de Economía Laboral, and the 57th ERSA Congress for their comments to an earlier draft. The first and second authors were partially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness under project ECO2017-82227-P. The third author has been partially supported by Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness under project CSO2015-69439-R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

APPENDIX 1: Tables and Figures

APPENDIX 2: Elements of actual unemployment

Figure 9 illustrates the different components of the actual unemployment rate. The curve \( {L}_{it}^S \) is the labour force and displays a positive slope. This is because, as the market wage increases (wit), more individuals join the labour market given that their “static” reservation wage (or that of the choice model between consumption and leisure) is lower than the market wage.

The curve \( {N}_{it}^S \) shows the actual labour supply. The difference between \( {L}_{it}^S \) and \( {N}_{it}^S \) establishes that not all active workers are immediately available for work. As the market wage increases and rises above the “dynamic” reservation wage (or that of the job search theory), more workers will accept the jobs they find. For this reason, the distance between \( {L}_{it}^S \) and \( {N}_{it}^S \) is lower for higher wages. This difference between the two previously mentioned curves is frictional unemployment (\( {U}_{it}^F \)).

Figure 9 also shows two situations of the demand for employment, depending on how aggregate production stands. Situation (y0) represents economic expansion, whereas situation (y1) reflects an economic recession. Point “A” shows how, in a situation in which production is booming and the market wage is at its equilibrium level, with a \( {L}_{i,t}^D\left({y}_0\right) \) demand of work, there are unemployed workers due to the presence of frictional unemployment.

In addition, the existence of a collective bargaining system impacts on the mechanism for establishing wages by fixing a “collective bargaining” (\( {w}_{it}^{CB} \)) wage which is above the competitive equilibrium wage (\( {w}_{it}^{PC} \)). This is one example of institutional inflexibility which leads to an excess of labour supply, and triggers structural unemployment (\( {U}_{it}^{ST} \)).Footnote 56 As in the previous case, some structural unemployment would also exist even if demand for work were \( {L}_{i,t}^D\left({y}_0\right) \), which is associated to an economic boom. Several studies (Bentolila and Jimeno 2003; Simón et al. 2006; Bande et al. 2008) point out that the “inflexibility” of wages prevents these from acting as an equilibrium mechanism in the Spanish labour market.Footnote 57 In line with this, “via price” adjustment does not function “correctly”, thus leading to adjustments in the labour market occurring “via quantity.Footnote 58

Finally, in Fig. 9, cyclical unemployment is reflected in the horizontal distance between curves \( {L}_{it}^D\left({y}_0\right) \) and \( {L}_{it}^D\left({y}_1\right) \). This kind of unemployment may be corrected in the short term by applying expansive aggregate demand policies.

APPENDIX 3: Model with spatial lags

This additional specification seeks to correct spatial dependence in the estimation. To do this, we incorporate the spatial lag of the dependent and independent variables into the baseline model. In this case, we perform a specification based on the idea of the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM)Footnote 59 as shown in the following expression:

Uit = β0 + ρWUit + β1Xit + β2Yit + β3Zit + δD2001 + γ1WXit + γ2WYit + γ3WZit + vit + μi where W is the spatial weight matrix (Knn = 5); WUit is the spatial lag of the dependent variable; WXit captures the effect of the industry composition of labour in neighbouring provinces; WYit are the spatial interactions of the demographic variables and WZit is a vector of spatial lags for the human capital of the active population. We compute this new specification so as to test whether spatial dependence in our model is a consequence of endogenous or exogenous interaction effects.

The results of the estimated model are presented in table 5. The spatial lag of the dependent variable shows a positive and statistically significant coefficient as well as the majority of the spatial lags of the independent variables. This implies that the values of the dependent and independent variables in the neighbouring provinces capture part of the variability in the unemployment rate.Footnote 60 In a second step, we carried out the same spatial dependence analysis as in the baseline model within the main text, with results still pointing to the presence of positive spatial correlation. It can therefore be concluded that spatial dependence also seems to be caused by factors different from those variables considered in this paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cuéllar-Martín, J., Martín-Román, Á.L. & Moral, A. An Empirical Analysis of Natural and Cyclical Unemployment at the Provincial Level in Spain. Appl. Spatial Analysis 12, 647–696 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-018-9262-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-018-9262-x