Abstract

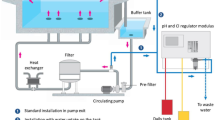

Thermal waters have been used from ancient times. From those early experiences and the consecutive improvements in the understanding and treatment of these waters, all around the world different cultures and communities have used natural structures or have built facilities for the best use and exploitation of the mineral spring water. Nowadays thermal spas, inheritors of a rich and long tradition from the ancient world, combine classical techniques with innovative proposals. Thus, the introduction and implementation of new technologies in bathtubs, swimming pools, showers, saunas, etc., allow the efficient optimization of thermal techniques and hydrotherapy facilities. Moreover, the development of health tourism offers a new way to understand the use of thermal water, which requires higher quality and specialization of the spa services. Every year thousands of people travel to Europe for a healthy holiday and to improve their welfare and wellbeing. Resorts, spas, thalassotherapy centers and thermal spas that use hot thermal water utilize bath techniques, respiratory applications, pressure techniques, wraps, etc. These techniques use facilities and amenities such as swimming pools, bathtubs, showers, sprays and stoves, among others. One can also find peloids (thermal mud) and any kind of clay and herbal wraps. From the practices developed in Roman times, but especially from the first hydrotherapy techniques described by Priessnitz until today, there have been numerous innovations that have enabled the spas to adapt to the demands and needs of a new type of customer. Nowadays, there are companies specializing in the design and innovation of hydrotherapy that favour the modernization of existing spas or the emergence of new spas. The highlights are control and automation; new materials; design and architecture designed by prestigious architects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As early as the second century AD, medical texts already identified healing spas—natural mineral water baths—(αὐτοφυῶν λουτρῶν) as opposed to common heated common water baths (λουτρόν)—without an adjective—or “artificial baths” (τῶν ἐξ ἐπιτεχνήσεως) (Antilus, in Orib. 10, 3). In this sense, in Roman times, the feminine plural word, aquae (“the waters”), was mainly used to refer to these medicinal mineral waters, as defined by Varro (Ling. 9, 41, 68–69); or, more specifically, aquae calidae, fontes calidi or fontis medicati (analyzed in Mudry 2015, p. 70).

These are mentioned, for instance, by several authors in the compilation made by physician Oribasius (fourth century AD, Collectanae medicinalia), or the well-known works of authors such as Vitruvius (8, 3, 1), Pliny the Elder (31, 1–5) or Seneca (Nat, 3, 20–24), explicitly referring to the mineral formulation of these waters and not just to their temperature, which are linked to the health properties of these springs (s. Oró Fernández 1996 on this topic).

The Roman model, however, was pretty close to what we know today. If we examine the concept developed around thermal sites such as Baia (in the Gulf of Naples) or Bath (in South-West England) (Fig. 2), to name the most representative examples, we cannot find major differences from the image of a European spa around the nineteenth century (Maraver 2006).

In this regard, many religious orders increasingly undertook and started to manage these resources.

See Cressier (2002) on Arab terminology and design of these spas.

The erection of hospitals linked to these mineral springs, such as St. John's in Bath, England (twelfth and thirteenth centuries), in Tripergole, Italy (fourteenth century), or in Caldas da Rainha, Portugal (fifteenth century) with the first water tests, are also proof of this interest.

Particularly remarkable are pioneering publications, especially in the Italian Peninsula: for instance, the well-known works of Pietro di Eboli, who described different mineral water baths and the treatments in Baia in the thirteenth century; or Gentile da Foligno, in the fourteenth century, who wrote about Tuscan baths, thus starting a new literary trend, De Balneis, which were treatises on spas (García Ballester 1998). For a summary of some references on the works on Thermalism from different perspectives and periods, see Gerbod (2004); and more specifically (Guérin-Beauvois and Martin 2007; Nicoud and Boisseuil 2010; Boisseuil 2015).

E.g. Surintendance générale des bains et fontaines du Royaume, created by French king Henri IV in 1605; or Cuerpo de Médicos Directores de Baños in Spain, created by Ferdinand VII in 1816.

As described by Seneca (Epist. 86, 4) writing about the baths of Publius Cornelius Scipio, comparing the habits in second-century-BC baths to contemporary baths in the first century AD.

The most significant examples can be found in some urbs, like in the city of Rome, still partially visible today, such as the Baths of Caracalla and Diocletian; or in other parts of the Empire, like the Baths of Antoninus in the ancient Carthago (Tunisia), or the Imperial Baths in Trier (Germany), among others.

Roman thermal spas with large pools can be found all over the Empire. Some of the most well-known and monumental, however, are those in Bath (England) and Baia (Italy, first model of spa villa), Hammat-Gader (Israel), Hammam Salehine (Algeria), Néris-les-Bains (France), Caldes de Montbui (Spain) or Chaves (Portugal), among many others.

These were probably conceived to allow bathers to use these waters unhurriedly and to give them the chance to sit and partially submerge in water. See thermal spas above, as well as Badenweiler (Germany), Jebel-Oust (Tunisia) or Aquae Tauri (Civitavecchia, Italy).

Recommendations based, for example, on the patient's full or part immersion in these waters to peacefully benefit from mineral vapors, in a gradual process of adaptation of 21 days, reaching a maximum of 2 h/day in the thermal spa (Herodotus in Orib. X, 5).

See Tölle-Kastenbein (1990) for a specific study on this.

An example of this survival of forms and treatments is documented, for instance, in the medieval bathhouse of Bagno de Vignoli (Nicaud 2015, p. 90) and other Italian examples (Boisseuil 2008). We have very few examples of these infrastructures, as the reutilization of hot springs and later renovations have practically obliterated all evidence in most cases (Boisseuil 2008).

The work of Pietro di Eboli (thirteen century) shows later examples of these structures, an accurate image of the importance of sulphur treatments in the area of Pozzuoli. This use model is still present today in modern spa facilities, such as Baños de Fitero, among others, where steam treatments are conducted in a cave space in the hill next to the spa resort.

Thus, this author mentions that mineral water steam baths are certainly more effective and recommends following the steam bath with an immersion, a Vichy or affusion shower or a sea bath.

As mentioned above, the use and study of these vapors' health properties was frequent in the area of Baia and Naples (Conforti 2015), but also in other areas such as Lipari and, very likely, in Thermopylae (Greece), among others.

References

Alen E, De Carlos P, Domínguez T (2014) An analysis of differentiation strategies for Galician thermal centres. Current Issues in Tourism 17(6):499–517

Boisseuil D (2008) La douche thermale : une technique thérapeutique nouvelle dans l’Italie du Quattrocento ? In Durand A (ed) Jeux d’eau : moulins, meuniers et machines hydrauliques, XIe-XXe siècle. Etudes offertes à Georges Comet. Publications de l’Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, pp 59–74

Boisseuil D (2015) La cure thermale dans l’Italie de la fin du Moyen Âge et du debut du XVIe siècle. In: Scheid J, Nicoud M, Boisseuil D, Coste J (dirs) Le thermalisme. Approches historiques et archéologiques d’un phenomène culturel et médical, Paris, pp 105–122

Broise H (2015) « Thermes ‘classiques’ et thermes ‘curatifs’. Réflexions sur l’architecture et l’organisation interne des thermes utilisant l’eau des sources thermales chaudes durant l’Antiquité » , In: Scheid J, Nicoud M, Boisseuil D, Coste J (dirs) Le thermalisme. Approches historiques et archéologiques d’un phenomène culturel et médical, Paris, pp 45–64

Broise H, Curie C (2014) Contribution à l’étude des travertins carbonatés à l’analyse diachronique, fonctionnelle et architecturale des thermes: l’exemple des thermes du sanctuaire de Djebel Oust (Tunisie). In: M-F Boussac, S Denoix, Th Fournet y B. Redon (eds), Balaneia. Thermes et hammams. 25e siècles de bain collectif -Proche Orient, Égypte et Péninsule Arabique- (Damas 2–6 Novembre 2009), Damas, pp 753–784

Caelius Aurelianus, De morbus Chronicorum (Concerning Acute and Chronic Diseases)

Celsus, Aulus Comelius Celsus, De medicinae (On Medicine)

Conforti M (2015) “Subterranean fires and chemical exhalations: mineral waters in the Phlegraean Fields in the early modern age ». In: Scheid J, Nicoud M, Boisseuil D, Coste J (dirs) Le thermalisme. Approches historiques et archéologiques d’un phenomène culturel et médical, Paris, pp 123–137

Cottereau du Clos (1671) Observations sur les eaux minérales de plusieurs provinces de France faites en l’Académie Royale des Sciences en l’année 1670 & 1671. Reims, Paris

Cressier P (2002) Prendre les eaux en Al-Andalus. Pratique et fréquentation de la hamma, Médiévales 43:41–54

Faubel-Serra V, Romero-Valiente J (2011) Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio 50(2):XIX–XXII

Fournet Th, Redon B (2010) Le bain grec à l’ombre des thermes romains. Les dossiers d’Archéologie 342:56–63

García Ballester L (1998) Sobre el origen de los tratados de baños (de balneis) como género literario en la medicina medieval. Cronos 1:7–50

Gerbod P (2004) Loisirs et santé. Les thermalismes en Europe des origines à nos jours. Honoré Champion, Paris

Gomes C, Carretero I, Pozo M, Maraver F, Cantista P, Armijo F, Legido JL, Teixeira F, Rautureau M, Delgado R (2013) Peloids and pelotherapy: historical evolution, classification and glossary. Appl Clay Sci 75–76:28–38

González Soutelo S (2007a) En los orígenes de los balnearios, spas y centros de talasoterapia. Los establecimientos termales en el mundo antiguo. Parte I. Tribuna Termal 5:55–61

González Soutelo S (2007b) En los orígenes de los balnearios, spas y centros de talasoterapia. Los establecimientos termales en el mundo antiguo. Parte II. Tribuna Termal 6:34–39

González Soutelo S (2011) El valor del agua en el mundo antiguo: sistemas hidráulicos y aguas mineromedicinales en el contexto de la Galicia romana. Fundación Barrié de la Maza, A Coruña

González Soutelo S (2014) Medicine and Spas in the Roman period: the role of doctors in establishments with mineral-medicinal waters. In: Michaelides D (ed) Medicine in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp 200–210

Guérin-Beauvois M, Martin JM (eds) (2007) Bains curatifs et bains hygiéniques en Italie de l’Antiquité au Moyen âge (actes du colloque tenu à Rome les 22 et 23 mars 2004). École française de Rome, Paris

Gutenbrunner C, Bender T, Cantista P, Karagülle Z (2010) A proposal for a world-wide definition of health resort medicine, balneology, medical hydrology and climatology. Int J Biometeorol 54(5):495–507

Hauser S, Zumthor P, Binet H (2007) In: Zumthor P (ed) Peter Zumthor therme vals. Scheidegger and Spiess, Zurich

Horatius, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Epistulae (Letters)

Jackson R (1990) Waters and spas in the classical world. Med Hist Suppl 10:1–13

Khan MW, Choudhry MA, Zeeshan M, Ali A (2015) Adaptive fuzzy multivariable controller design based on genetic algorithm for an air handling unit. Energy 81:477–488

Knorst-Fouran A, Casas LM, Legido JL, Coussine C, Bessieres D, Plantier F, Lagiere J, Dubourg K (2012) Influence of dilution on the thermophysical properties of Dax peloid (TERDAX (R)). Thermochim Acta 539:34–38

Limón Montero A (1697) Espejo cristalino de las aguas de España: hermoseado y guarnecido con el marco de variedad de fuentes y baños cuyas virtudes se examinan... Alcalá de Henares

Maraver F (ed.) (2006) Establecimientos balnearios: historia, literatura y medicina. Balnea 1:1–186

Martial, Marcus Valerius Martialis, Eppigrammaton libri (Epigrams)

Mourelle ML (coord.) (2009) Técnicas hidrotermales y estética del bienestar, Madrid

Mudry Ph (2015) Le thermalisme dans l’antiquité. Mais où sont les médicins ? In: J Scheid, M Nicoud, D Boisseuil, J Coste (dirs) Le thermalisme. Approches historiques et archéologiques d’un phenomène culturel et médical. Pigeaud Richard, Paris, pp 65–78

Nicaud M (2015) Le thermalisme médiéval et le gouvernement des corps : d’une recreatio corporis à une regula balnei. In: J Scheid, M Nicoud, D Boisseuil, J. Coste (dirs) Le thermalisme. Approches historiques et archéologiques d’un phenomène culturel et médical. CNRS: Paris, pp. 79–104

Nicoud M, Boisseuil D (2010) Séjourner au bain. Le thermalisme entre médicine et société (XIVe-XVIe siècles). Presses Universitaires de Lyon, Lyon

Oribasius, Collectanae medicinalia, Oeuvres complètes, I-VI, U.C. Bussemaker y Ch.V. Daremberg (trads.) (1851–1876), Paris

Oró Fernández ME (1996) El Balneario romano: aspectos médicos, funcionales y religiosos, El balneario romano y la cueva negra de Fortuna (Murcia). Homenaje al profesor PH. Rahtz. Antigüedad y Cristianismo, nº13, Murcia, pp 23–151

Pliny the Elder, Gaius Plinius Secundus, Naturalis historiae (The Natural History)

Pliny the Younger, Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, Epistulae (Letters)

Routh HB, Bhowmik KR, Parish LC, Witkowski JA (1996) Balneology, mineral water, and spas in historical perspective. Clin Dermatol 14(6):551–554

Sammama E (2015) Sources chaudes et eau médicale: un « thermalisme » grec ? In: J Scheid, M Nicoud, D Boisseuil, J Coste (dirs.) Le thermalisme. Approches historiques et archéologiques d’un phenomène culturel et médical, Paris, pp 13–30

Seneca (The Younger), Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Naturales Quaestiones (Natural questions)

Seneca (The Younger), Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Epistulae morales ad Lucilium (Moral letters to Luculius)

Tölle-Kastenbein R (1990) Duschen in archaischer Zeit, Frontinus-Symposium beim Kongress “Wasser Berlin”, Jahrestagung 1989 in Hannover und weitere Beiträge zur historischen Entwicklung der Technik, 14:191–201

Turner W (1568) A book of the natures and properties as well od the Baths in England as of other baths in Germany and Italy, London

Varro, Marcus Terentius Varro, De lingua latina (On the Latin Language)

Vitruvius, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, De architectura (Ten Book son Architecture)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the special issue on Sustainable Resource Management: Water Practice Issues.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez Pérez, C.P., González Soutelo, S., Mourelle Mosqueira, M.L. et al. Spa techniques and technologies: from the past to the present. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 5, 71–81 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-017-0136-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-017-0136-1