Abstract

This article proposes the application of the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) as a framework for promoting inclusion in outdoor learning in primary school settings. The authors conceptualise outdoor learning, highlighting the potential for more child-initiated experiential learning. Yet this paper is not concerned only with outdoor learning, but with the inclusion of all learners in outdoor learning, through enactment of the curriculum in mainstream schooling. The diverse profile of children in primary schools calls on teachers to prepare teaching, learning and assessment activities to address a wide range of social, emotional, physical, cognitive and cultural needs. Contemporary researchers recognise outdoor learning as an effective pedagogy to promote inclusion and therefore reduce the barriers for full participation in the primary classroom. UDL is offered as a framework for planning outdoor learning to support delivery of curricula that are responsive to the needs of all learners. UDL is underpinned by three principles: multiple means of engagement, representation, expression and action. Two vignettes are shared to illustrate how these principles can be applied to outdoor learning in a meaningful and sustained way. The article highlights the benefits for teachers and learners of applying UDL principles to outdoor learning to promote inclusion in the diverse primary class.

Similar content being viewed by others

Outdoor learning for all children

The fundamental belief on which this paper is premised is that all children should have equal access to outdoor learning, highlighting issues of inclusion and diversity. All children should be connected with nature, through education that encourages environmental awareness and stewardship. Indeed, children’s rights to an education that addresses the development of respect for the natural environment is enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (The United Nations, 1989). We argue that this can be achieved through outdoor learning, if undertaken in appropriate ways.

Outdoor learning, at an entry level, can be described as teaching and learning which could take place in the classroom but is taught outside the classroom with little or no connection to the environment or place. At a deeper level, it can be described as teaching and learning which supports the development of children’s knowledge and understanding of their environment through direct engagement. At an even deeper level, it can be described as a pedagogy which supports children’s learning and development across a range of domains with the outdoors providing the context, resources, setting and/or space for rich experiential and authentic learning. We draw on this even deeper level and conceptualise outdoor learning as learning that takes place not just outside the classroom but outdoors. Such outdoor learning promotes a change of location rather than a change of curriculum (Lloyd, 2018).

At this level the outdoors allows for experiential learning in authentic settings, where learning is carried out in real-world contexts, which have personal relevance to the learners. The teacher’s role shifts to one of observer and facilitator which offers opportunities for the emergence of different relationships and group dynamics. Here outdoor learning can work to disrupt the usual culture of adult dominance in learning situations, enabling children to experience more freedom to initiate their own learning experiences, to play for longer periods without interruptions and to show independence of thinking and action (Waite and Davis, 2007). This links with Waite and Pratt’s work (2017) on the cultural density of places, where outdoor spaces and places unfamiliar to staff and students are considered culturally light as they bring fewer rules and/or routines allowing for more playful child-initiated learning and egalitarian management of how time is spent (Waite, Rogers and Evans, 2013).

Yet this paper is not concerned only with outdoor learning, but with the inclusion of all learners in outdoor learning, through enactment of the curriculum in mainstream schooling. Quality inclusive and equitable education for all is enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal 4 (United Nations 2021) and specifically Target 4.5: by 2030 eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations. Teachers encountering heterogeneous classes need to be ready to include all learners. Readiness does not mean having a particular skill set; instead, we believe that the mind-set or attitude a teacher has about inclusion is the most important element of successful inclusion. Jorgensen (2018) defines inclusive education as school communities in which all students are presumed competent, are welcomed as valued members in the class, fully participate and learn alongside their same age peers and experience reciprocal social relationships. These are all seen as an integral part of successfully planning for and including all children into outdoor learning spaces.

Hopper (2017) recognises that there are many challenges facing teachers when considering issues associated with inclusion, planning, differentiation, and assessment. However, he describes how those teachers who plan for these challenges and take their lessons into the outdoors frequently find both their teaching and the children’s learning greatly enriched.

Other researchers have investigated outdoor learning and reached similar conclusions. Lloyd (2018), in her study of outdoor learning in a primary school setting, discovered that children who found the indoor classroom challenging, for the most part excelled outdoors. Furthermore, the results indicated that learning outside the classroom was beneficial to the children’s overall curriculum learning. Guardino, Hall, Largo-Wight and Hubbuch (2019) reported on a research project which explored the perceptions of kindergarten teachers and their students’ of teaching and learning in a traditional indoor classroom compared to a newly constructed outdoor classroom. Analysis revealed that the children with disabilities were less distracted and more on-task when working in the outdoor classroom (p. 113). Beames, Christie and Blackwell (2017) highlighted through a particular case study how the nature of outdoor learning, offering hands-on and interactive learning experiences, often breaks down barriers for individuals who find the constraint of an indoor environment a challenge. A study by Dahl, Standal and Moe (2018) on Norwegian teachers’ safety strategies for Friluftsliv excursions described how some teachers adapted their teaching to include all pupils, irrespective of differences and abilities, by using simpler forms of natural contexts and local places in their teaching practices, and trying to include a variety of skills, equipment and experiences.

Such changes in practice could be framed in a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) context. There has been little research connecting UDL and outdoor learning. Harte (2013) and Heugen (2019) have described using the UDL framework in early years settings. Importantly, Heugen suggests that “bringing together the UDL framework with research-based principles for implementing nature-based outdoor classrooms helps us move much closer to supporting children of all abilities to be a part of things – and thrive – outdoors” (p. 12). It is the connection between UDL and outdoor learning that sits at the heart of this paper.

The UDL framework is defined as a tool to maximize the teaching and learning process for all students (Center for Applied Special Technology [CAST], 2018). UDL is a set of principles for curriculum development and implementation that give all individuals equal opportunities to learn. It aims to improve the educational experience and outcomes for all students by introducing more flexible methods of teaching, assessment and service provision to cater for the diversity of learners in classrooms. This approach is underpinned by research in the field of neuroscience (CAST, 2018).

The universal design approach originated in the United States in the 1960s after the passing of the federal law Architectural Barriers Act of 1968. This law required universal access to buildings that were federally funded (Story, Mueller and Mace, 1998). In the 1980s the universal design approach was applied to education as UDL. At this time its application to the physical education context was still relatively new (CAST, 2018). In the time since UDL was applied to physical education specifically in the late 2000s, relatively little has been done in translating this knowledge to teacher practitioners in physical education and other more dynamic movement fields until recently (Lieberman, Grenier, Brian and Arndt, 2020). Previous UDL physical education articles have included strategies for general recommendations and rationale (Lieberman, 2017; Lieberman, Lytle and Clarcq 2008), community sports programs (Sherlock-Shangraw, 2013), severe disabilities in general physical education (Grenier, Miller and Black, 2017), early childhood motor skill (Taunton, Brian and True, 2017), and specific sports or activities (Grenier, Fitch and Young, 2018; Ludwa and Lieberman, 2019). This article expands the literature base for outdoor learning spaces.

A noticeable difference in the UDL approach compared to traditional models of “one size fits all” teaching is that variations in the curriculum are implemented in the lesson plan in advance and offered as a choice for all students instead of an afterthought (Lieberman, Lytle and Clarcq, 2008). The main purpose of this approach is to support the delivery of a curriculum that is completely accessible, meaningful, and a naturally challenging learning experience that meets the needs of every student (CAST, 2018).

There has been huge development in the theory and practice of UDL, since its inception in the 1990s. Over the last fifteen years, CAST and other researchers have expanded and developed the conceptual framing of UDL, reflecting significant developments in neuroscience, technology and the dynamic classroom experience. The three core principles remain the same and articulate the basic UDL premise that “to provide equitable opportunities to reach high standards across variable students in our schools, educators must provide” (Meyer, Rose and Gordon, 2014, p. 51) three things:

Multiple means of engagement to support affective learning (i.e., why we learn), multiple means of representation to support the ways in which we assign meaning to what we see and recognise (i.e., what we learn), multiple means of action and expression to support strategic ways of learning (i.e., how we learn). (Meyer, Rose and Gordon, 2014, p. 51)

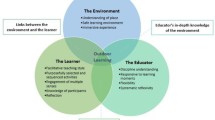

Through collaboration with contributors to the field, CAST has expanded the three principles by developing nine guidelines, each with multiple checkpoints offering specific approaches to implementation. These checkpoints are researched and applied in educational settings globally, allowing for continual refinement and enhancement of the framework over time. These detailed guidelines and checkpoints offer teachers an opportunity to effectively integrate the UDL principles into their teaching practices (see Fig. 1; CAST, 2018).

CAST 2018 Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

A key element in creating a universally designed learning environment lies in the course and curriculum design process. It is of great importance to acknowledge that this actually is a process. It includes the description of learning outcomes, fulfilment of competence standards, implementation through teaching and learning activities, and measurement through assessment methods. Equally important, this work is heavily affected by demands of national curricula regulations.

The principles of UDL and their relationship with outdoor learning

A fundamental goal of UDL is to anticipate and redress barriers to learning, using considered pedagogies to meet all learning needs and abilities through effective design. Such barriers could be physical, cognitive, cultural, social, and/or emotional. For the teacher planning outdoor learning, implementing effective instructional plans, focused on engagement and using flexible materials in meaningful ways, generates an inclusive environment for all learners. Enacting this inclusive environment in a meaningful and sustained way, is the real challenge for teachers. If pedagogy is guided by ill-defined goals and equipped with only conventional instructional methods, using inaccessible resources, and inflexible ways of demonstrating knowledge and understanding, the barriers to learning may be difficult to comprehend.

Accordingly, the UDL framework addresses the whole curriculum—goals, materials, methods, and assessments—to make it more accessible not only physically, but also intellectually and emotionally for all learners (Hitchcock, Meyer, Rose and Jackson, 2002; Jackson and Harper, 2005). In specific application, UDL challenges curriculum designers, teachers and assessors to, as Meyer, Rose and Gordon (2014) describe it: (1) “define goals that provide appropriate challenges for all learners, ensuring that the means is not a part of the goal” (p 71); (2) “use methods that are flexible and diverse enough to support and challenge all learners” (p. 78); (3) “incorporate materials that are flexible and varied and take advantage of the digital media” (p. 81); and (4) “implement assessment techniques that are sufficiently flexible to provide ongoing, accurate information to inform instruction and determine student understanding and knowledge” (p. 74).

Rose and Gravel (2010) advocate for teachers to integrate the three core principles of UDL into their instruction and assessment practices that are based on three interrelated types of brain networks (i.e., affective, recognition, and strategic networks). Deliberate planning of teaching, learning and assessment through these three brain networks provides a framework for planning instruction for all learners, not just those with disabilities or additional learning needs (Hall, Meyer and Rose, 2012).

UDL core principle 1: multiple means of engagement

The ultimate goal of applying the UDL framework is to enable learners to become experts (CAST, 2018). Arguably, a prerequisite for developing expertise is the engaged learner. Engagement can be fostered through designing a curriculum with built-in options for the learner to navigate the appropriate level of challenge and support. The UDL framework considers a learning environment that is flexible enough to account for learner variability; meeting the specific needs of every learner. To address varied learner capabilities and needs, multiple and flexible options for engagement in the learning process are used to support affective learning. Teachers planning outdoor learning can design, deliver and evaluate lessons that involve creating interest and offer learning opportunities that motivate and stimulate learners according to their personal backgrounds and interests.

Providing options for multiple means of engagement requires developing interest, purpose, challenge, motivation, and strong self-regulation as a learner. What UDL researchers call “self-regulation” is the ability to set motivating goals; to sustain effort toward meeting those goals; and to monitor the balance between internal resources and external demands, seeking help or adjusting one’s own expectations and strategies as needed (Meyer, Rose and Gordon, 2014, p.` 53). In practice, three broad types of options emerge: options for recruiting student interest, options for sustaining effort and persistence, and options for developing the ability to self-regulate (CAST, 2018).

For the teacher planning outdoor learning, it is crucial to design learning opportunities that offer engagement so each student can find a way “into” the learning experience, remain persistent in the face of challenge or failure, and continue to construct knowledge. As teachers, we can evaluate and differentiate our learner’s engagement in the outdoor learning environment. Some learners may find comfort in a new outdoor space and be highly engaged by the novel experience; others could be intimidated, feeling out of place, preferring the predictable routine and structure of the indoor classroom. Here Jorgensen’s (2018) point about reciprocal social relationships as a core element of inclusive education is important and strongly align with checkpoint 8.3: foster collaboration and inclusion. Reciprocal social relationships mean that all members of a group are seen as valuable and with skills to share (Jorgensen, 2018). Sometimes in inclusive settings, the dynamic becomes one of “helping” the person with a disability. In that dynamic, the helper/helped roles can be limiting, for both the identified “helper” – typically the student without a label – and the “helped” – typically the student with a label. Both students are set up to see the relationship as an unequal one. Instead, framing all relationships as reciprocal supports equitable connections. Building in reciprocity supports an inclusive mind-set in which all are equal members. This can be achieved in the outdoor contexts by encouraging and supporting opportunities for peer interactions and supporting and constructing communities of learners engaged in common activities or interests (CAST 2018) as evidenced in both vignettes shared later in the paper.

Providing options to sustain interest and promote engagement in outdoor learning demands corresponding flexibility in the learning context if each student is to experience an inviting, appropriately challenging, and supportive learning environment. A universally designed outdoor learning environment that is centred around specific content goals can capitalise on the built-in range of options in order to calibrate comprehension for each student. Of course, nothing can be truly universal. Flexibility offered in any given lesson cannot address every type of variability; rather it should be specific to the particular goal of a lesson. Prompts for the teacher taking learning outside the classroom to consider, in order to provide multiple means of engagement, include:

-

How does this lesson spark my students’ excitement and curiosity for learning and understanding their environment through direct engagement? (recruiting interest)

-

How does this lesson tackle potential challenges with focus and determination? (effort and persistence)

-

How does this lesson harness the power of my students’ emotions and motivation in learning? (self-regulation)

UDL core principle 2: multiple means of representation

To plan for and address inclusion in the outdoor learning environment, multiple and flexible methods of presenting information are used to support recognition of learning. Providing instructions, concepts and content through multiple methods such as discussion, readings, digital texts, and multimodal presentations can account for varied learner capabilities and needs. The teacher planning outdoor learning can present learning materials through a variety of media (visual, auditory, or tactile), and provide multiple examples that can be modified in complexity to reach every learner in the class. This supports Jorgensen’s (2018) core element of presuming competence. In the absence of conclusive data, educational decisions ought to be based on assumptions which, if incorrect, will have the least dangerous effect on the likelihood that students will be able to function independently as adults (Donnellan, 1984). If the assumption is that a child has a disability that prevents him or her from showing what they have learned but they are able to learn and benefit from instruction, professionals may give her opportunities to learn new skills. That is far less dangerous than denying a child access to academic and social opportunity and discovering later that she can learn but was not given opportunities to learn because she was perceived to be incapable (Jorgensen, 2018). It is essential for an inclusive learning environment that all children have the capacity to think, learn and understand and it is up to the teacher and other adults to have the right support and systems in place to help them succeed. This is evidenced in multiple ways in the vignettes which follow by connecting with various checkpoints, including through offering alternatives for auditory (1.2) and visual information (1.3), clarifying syntax and structure (2.2) and highlighting big ideas (3.2) (CAST 2018).

To become an expert learner, students must be afforded the opportunity to construct knowledge by perceiving information in their environment, observing patterns, understanding and integrating new information. For this to be achieved, learners interpret and manipulate a wide variety of symbolic representations of knowledge, and develop fluency in the skills for curating and recalling that information. Learners’ ability to perceive, interpret, and understand this knowledge is reliant upon the media and methods through which it is presented to them. For the outdoor learning environment to support learners in all of these recognition processes, three broad kinds of options for representation are needed: options for perception; options for language, mathematical expressions, and symbols; and options for comprehension (Meyer, Rose and Gordon, 2014).

The use of media, particularly printed materials, provides one example to explore the benefits of providing multiple means of representation to all learners in our classes. Individuals with sensory disabilities (e.g., blindness) or learning disabilities (e.g., dyslexia) may require different representations of information in order to access and comprehend its content. In this instance, the medium is a barrier to learning for the student with varied needs. Providing multi-modal/multi-media content supports those who absolutely require it, while also offering a rich cognitive learning environment for all learners to explore the content from multiple points of view for example tactile maps or a readily available glossary, as illustrated in the vignettes which follow.

Contextual, local knowledge may cause a barrier, in the absence of appropriate scaffolding, for the student who doesn’t comprehend local tacit knowledge shared by most others in her class (Meyer, Rose and Gordon, 2014, p. 54). For the teacher planning outdoor learning and embedding UDL in practice, it is important to recognise that learners in their contexts vary systematically and widely in all dimensions. Our students come from an increasingly diverse population whose knowledge of vocabulary, ability to decode symbols, comprehension of the structure of languages, and their familiarity with multiple languages is wide ranging. However, this variability is context-bound; and it emerges in interactions between learners and the learning environment over time (Meyer, Rose and Gordon, 2014, p. 54). To promote understanding of information, concepts, relationships, and ideas, it is critical for outdoor learning educators to provide multiple ways for learners to access them. Prompts for the teacher taking learning outside the classroom to consider in order to provide multiple means of representation include:

-

How are my students able to interact using multiple senses with the outdoor environment? (perception)

-

How are my students able to participate regardless of their background knowledge or understanding of language, text, or symbols? (language and symbols)

-

How are my students able to construct meaning and generate new understanding of information? (comprehension)

UDL core principle 3: multiple means of action and expression

The third principle in the UDL framework is concerned with supporting strategic ways of learning (i.e., how we learn). Affording opportunities for students to demonstrate their understanding in multiple ways, addresses varied capabilities and allows the learner to practice tasks with different levels of support and to demonstrate their knowledge and skills in a range of ways. Employing multiple means of action and expression, the teacher planning outdoor learning can support the development of expertise in executive functions such as: goal setting, self-monitoring, strategy development, and managing information and resources. Again, Jorgensen’s core element of presuming competence comes into play here by optimising access to tools and assistive technologies (checkpoint 4.2) to support children to success as seen in both vignettes shared in the next section.

Expert learners are provided with support to set appropriate, realistic goals and are empowered to monitor their progress. This involves setting a goal at an appropriate level of difficulty and being flexible with strategies (i.e., adapting an alternative approach when needed). Primary school learners may not comprehend what is required in being an expert, so they might approach learning outdoors through trial and error, persevering with an unproductive strategy or trying various other approaches that might be “off track.” Students who have difficulty with organising and planning, or who have never been taught those strategies, may not even know that goal setting is an option. For learners who don’t receive effective guidance and feedback, they have little comprehension of success or failure. It is imperative to provide students with models and examples and to offer guides and supports for setting and pursuing goals. Prompts for the teacher taking learning outside the classroom to consider in order to provide multiple means of action and expression can include:

-

Does my lesson have accessible materials and tools for students to interact with in the outdoor space? (physical action)

-

Are there multiple ways for my students to construct, communicate, and share ideas in a way that works for them? (expression and communication)

-

How does the outdoor learning environment lesson provide support for my students to plan and get the most out of the lesson? (executive functions)

Two vignettes

In the following vignettes, example activities from the USA and Ireland are offered both to exemplify the application of the UDL framework to lessons and units of work and to further demonstrate the potential for rich integrated, connected and inclusive curricular learning through a pedagogy of outdoor learning. Where specific actions support the UDL checkpoint (as per Fig. 1), these are noted.

Vignette 1: Universal design for learning applied to a geocaching context

Sari and Ibrahim are in fourth grade and their class is going to do a geocaching unit. Geocaching is an outdoor recreational activity, in which participants use a Global Positioning System receiver or mobile device and other navigational techniques to hide and seek containers, called “geocaches” or “caches,” at specific locations marked by coordinates. Sari has cerebral palsy and she uses a walker. Ibrahim just immigrated from Syria and he has limited English vocabulary but follows directions well with gestures. The evident barriers for Sari are walking on the grass as well as holding the GPS while walking. The barriers for Ibrahim are his limited vocabulary and comprehension of the directions from the GPS. They are very excited to join their class for this new unit with their friends. The teacher wants to ensure that everyone is included in every part of the program. Mrs. Tully is the teacher for this unit and will be applying the UDL framework to this unit.

For her multiple means of action and expression, Mrs. Tully pairs up the students so they have a partner (5.3; 8.3). She found a phone holder for the GPS to hook onto Sari’s walker (4.1), and Sari could choose that strategy and/or have her partner hold the GPS (7.1). Mrs. Tully sets a clear goal for them, which was to reach 3–4 caches during each class period (6.1). Mrs. Tully provides feedback during the lesson and helps Sari to navigate the smoothest path to the caches on the first lesson so she can experience success.

For multiple means of engagement, she finds out that most of her students really love the movies Frozen II, Star Wars, and the musician Justin Bieber. Her geocache objects relate to these three interests of her students (7.2). This is a great motivator for them to stay focused on the eight caches that are out there. She ensures that the geocaches she picks are on even grass surfaces or off a dirt road for easy access (7.3). Mrs. Tully also has her students who have smart watches and activity trackers track the distances they walk during class to help motivate them to be active during the activity. This additional motivation helps them keep moving throughout the lesson.

Lastly, for multiple means of representation she instructs using visual instructions as well as visual maps and auditory cues with little terminology in between (1.2) and asking each student to describe how to get to each cache (5.1; 6.2). This ensured that each student knew their process and GPS coordinates for each cache. With partners every student met their goals and enjoyed their geocaching unit.

Vignette 2: Universal design for learning applied to a science lesson focussed on environmental awareness and care

Mr. Smith is a second grade teacher in a large urban school in Dublin. He plans a series of lessons to enable the children to identify and help to implement simple strategies for protecting, conserving and enhancing the environment in line with the science curriculum (DES/NCCA, 1999). Tariq is an asylum seeker, who has been living in Direct Provision housing for over two years, with limited access to play spaces and lack of opportunity for social and extra-curricular activities. He has also been exposed to racism outside of school. Mary is autistic and struggles particularly with verbal and non-verbal communication with her peers and changes in routine. When her routine is not consistent she may shut down and has occasionally had a tantrum during class. She has a strong interest in music. The evident barriers for Mary are her difficulties with peer communication during group activities and the change in routine by taking learning outside the classroom. The evident barriers for Tariq are the potential for him to feel unsafe in the public park, and his lack of experience of play spaces, particularly with peers.

Mr. Smith did some work with his class in a previous lesson on developing an enquiry focus that was relevant and of interest to them (7.2), then this next lesson is focussed on “how can our local park be improved to make it better for us?” Before going outside, Mr. Smith shows a map on the interactive whiteboard of the route they will take to the park (1.2) and orally describes how they will get there and back (1.3; 2.5). He uses the main cues for the lesson in a short rhyming song to engage Mary and her classmates (3.4). He then shows a map of the park and highlights the area they will be working in and where to sit when they get to the park (1.2; 7.3). He explains the key features of the map, specifically the map key in everyday language (2.2; 2.4). He explains that they will be walking in pairs with their “buddy” (7.3) and each pair has a map with the key features they will be considering. Finally, he reminds them of what the focus of the lesson is and supports recall of specific vocabulary from previous lessons (2.1; 3.3). On arrival Mr. Smith uses a picture exchange communication (PECS) Board with Mary to show her the symbols for walking, playground, gardens, and a bench (2.1). He then starts class by walking the children around the perimeter of where they will be working (1.3; 7.3) and then gives them time to explore this area which includes a small wooded area, some flower beds and a playground (7.1). Walking around the perimeter serves two purposes, both of which support safety: to set the boundary and to further familiarise the children with the space they will be working in. This also helps Mary understand the space in which she is expected to work and minimises the threat of the public space for Tariq (7.3).

In addition to the above, for multiple means of representation, Mr. Smith explains orally to the children that they have 20 min to investigate how the park could be made better for them. He provides visual cue cards around the different themes with key questions on them (1.2; 2.4; 3.2). He also has maps for the children of the space with key features highlighted to aid their thinking (2.5).

In addition to the earlier ones identified, for multiple means of engagement, the children choose who they work with and in what size group and through collaboration choose their particular focus: litter or play spaces (7.1; 7.2; 8.3). Mr. Smith has prepared some simple worksheets with key words with accompanying visuals on them to guide the children’s investigations should they want them (8.2). Before they embark on their investigation, he asks them to restate the purpose of the investigation (8.1). The children are given independence and time to explore the area allowing for child led learning (7.1; 8.3).

For multiple means of action and expression, he has provided clipboards and colouring pencils, hand held video cameras and magnifying glasses to offer choice in how the children engage and respond to the park environment (4.1; 5.1; 7.1). Mr. Smith has several timers for children who would like to know how much time they have left in their lesson (6.4). He allows them to answer his guiding questions in multiple ways such as drawings, videos, description, or verbal explanation.

Tariq spends most of his time running around and exploring the space with two of his classmates. He talks with them about the games he played in Karachi. Mary and her buddy find some quiet space, and having collected some sticks and small stones in the wooded area, Mary begins to explore the different sounds they make.

Mr. Smith finishes the lesson by inviting children to share, through visual, oral, tactile or technological means, one thing they would like to see changed in their park (5.1). Mary shares her picture of a big wooden xylophone. Tariq acts out playing football and says that there is not enough space to play football! Mr. Smith then asks the children to reflect on one thing they liked about the lesson and one thing they found difficult, with choice in how they capture this (6.4; 9.3).

In the next lesson, children are given a choice of how to demonstrate their learning from the previous lesson catering for multiple means of action and expression (5.1; 5.2) to highlight key issues in response to their enquiry (5.3).

Conclusions

This article has demonstrated the potential for an integrated, connected, and inclusive curriculum through outdoor learning. Offering students the opportunity to learn through authentic, local outdoor contexts supports experiential learning and effectively develops curriculum learning. Furthermore, in the context of increasing diversity in our schools, this article has uniquely demonstrated the application of UDL principles for inclusion in outdoor learning. A strong case has been argued for the use of UDL principles for inclusion when planning for outdoor learning to support all learners to thrive and succeed.

This article concludes with a call to action for outdoor learning enthusiasts, educators and practitioners. There is a gap in the research and practice literature around the use of UDL in outdoor learning contexts, indeed, more generally, research into UDL as a practice is just beginning (University of California Berkeley, 2022). This is a potentially rich theme which needs further research evidence and stories from practice to determine its real potential as a tool for inclusion for all learners. Barriers to the implementation of UDL, as identified by Katz (2015), include the need for professional learning communities. A community of practice would add significantly to the existing knowledge and understanding and could open up opportunities for professional learning for those working in outdoor learning and education settings as well as for initial and continuing teacher professional development. The Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices (S-STEP) special interest group with the American Educational Research Association (AERA) offers a model from which such a community of practice could learn. This approach to professional learning has been successful across a wide range of disciplines and interest areas, including a self-study project focused on Meaningful Physical Education (MPE) which offers a useful insight into this process (Ní Chróinín, Beni, Fletcher, Griffin and Price, 2019).

Inclusion is an ever-present and evolving principle, as our societies and cultures go through rapid change. UDL might be one approach to ensure that all learners in schools can benefit from and enjoy full participation in outdoor learning to meet curriculum goals.

References

American Educational Research Association (2022). Self-study of teacher education practices SIG. AERA.net. https://www.aera.net/SIG109/Self-Study-of-Teacher-Education-Practices

Beames, S., Christie, B., & Blackwell, I. (2017). Developing whole school approaches to integrated indoor/outdoor teaching. In S. Waite (Ed.), Children Learning Outside the Classroom From Birth to Eleven (2nd ed., pp. 82–93). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) (2018). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Dahl, L., Standal, O. F., & Moe, V. F. (2018). Norwegian teachers’ safety strategies for Friluftsliv excursions: Implications for inclusive education. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 19(3), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1525415

Department of Education and Science/National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (1999). Primary school curriculum: Science. https://www.curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/346522bd-f9f6-49ce-9676-49b59fdb5505/PSEC03c_Science_Curriculum.pdf

Donnellan, A. M. (1984). The criterion of the least dangerous assumption. Behavioral Disorders, 9(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874298400900201

Grenier, M., Fitch, N., & Young, J. C. (2018). Using the climbing wall to promote full access through Universal Design. PALAESTRA, 32(4), 41–46. https://js.sagamorepub.com/palaestra/article/view/9527

Grenier, M., Miller, N., & Black, K. (2017). Applying Universal Design for Learning and the inclusion spectrum for students with severe disabilities in general physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 88(6), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2017.1330167

Guardino, C., Hall, K. W., Largo-Wight, E., & Hubbuch, C. (2019). Teacher and student perceptions of an outdoor classroom. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 22(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-019-00033-7

Hall, T. E., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (Eds.). (2012). Universal Design for Learning in the classroom: Practical applications. Guilford Press

Harte, H. (2013). Universal design and outdoor learning. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 41(3), 18–22. http://dl.icdst.org/pdfs/files1/60e0fa65d263ac3eea972ee12f17c062.pdf

Heugen, K. (2019). Bringing the benefits of nature to all children. The Active Learner, Highscope’s Journal for Early Educators, Spring, 12–13, https://highscope.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HSActiveLearner_2019Spring_sample.pdf

Hitchcock, C., Meyer, A., Rose, D., & Jackson, R. (2002). Providing new access to the general curriculum: Universal Design for Learning. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 35(2), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990203500201

Hopper, R. (2017). Special educational needs and disability and learning outside the classroom. In S. Waite (Ed.), Children Learning Outside the Classroom From Birth to Eleven (2nd ed., pp. 118–130). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Jackson, R., & Harper, K. (2005). Teacher planning for accessibility: The universal design of learning environments. In D. H. Rose, A. Meyer, & C. Hitchcock (Eds.), The universally designed classroom: Accessible curriculum and digital technologies (pp. 101–124). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press

Jorgensen, C. M. (2018). It’s more than” just being in”: Creating authentic inclusion for students with complex support needs. https://www.slideshare.net/BrookesPubCo/its-more-than-just-being-in-creating-authentic-inclusion-for-students-with-complex-support-needs-presented-by-cheryl-m-jorgensen-phd

Katz, J. (2015). Implementing the three block model of Universal Design for Learning: Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy, stress, and job satisfaction in inclusive classrooms K-12. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2014.881569

Lieberman, L., Lytle, R., & Clarcq, J. A. (2008). Getting it right from the start. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 79(2), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2008.10598132

Lieberman, L. J. (2017). The need for Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 88(3), 5–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2016.1271257

Lieberman, L., Grenier, M., Brian, A., & Arndt, K. (2020). Universal Design for Learning in physical education. Human Kinetics, Inc

Lloyd, A. (2018). Outdoor learning in primary schools: Predominately female ground. In T. Gray & D. Mitten (Eds.), The Palgrave International Handbook of Women and Outdoor Learning (pp. 637–648). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53550-0_43

Ludwa, N., & Lieberman, L. (2019). Spikeball for all: How to universally design spikeball. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 90, 48–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2019.1537425

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing. http://udltheorypractice.cast.org/

Ní Chróinín, D., Beni, S., Fletcher, T., Griffin, C., & Price, C. (2019). Using meaningful experiences as a vision for physical education teaching and teacher education practice. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(6), 598–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1652805

Rose, D. H., & Gravel, J. W. (2010). Universal Design for Learning. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education (3rd ed). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00719-3

Sherlock-Shangraw, R. (2013). Creating inclusive youth sport environments with the Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 84, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2013.757191

Story, M. F., Mueller, J. L., & Mace, R. L. (1998). The Universal Design file: Designing for people of all ages and abilities. North Carolina State University College of Design. https://projects.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/pubs_p/pudfiletoc.htm

Taunton, S. A., Brian, A., & True, L. (2017). Universally designed motor skill intervention for children with and without disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 29(6), 941–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-017-9565-x

United Nations (1989). The United Nations conventions of the rights of the child. https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention

United Nations (2021). Goal 4. Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

University of California Berkeley (2022). Berkeley Universal Design for Learning. https://udl.berkeley.edu/udl-research

Waite, S., & Davis, B. (2007). The contribution of free play and structured activities in Forest School to learning beyond cognition: an English case. In B. Ravn, & N. Kryger (Eds.), Learning beyond cognition (pp. 257–274). The Danish University of Education

Waite, S., & Pratt, N. (2017). Theoretical perspectives on learning outside the classroom - relationships between learning and place. In S. Waite (Ed.), Children Learning Outside the Classroom From Birth to Eleven (2nd ed., pp. 7–22). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Waite, S., Rogers, S., & Evans, J. (2013). Freedom, flow and fairness: Exploring how children develop socially at school through outdoor play. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 13(3), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2013.798590

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, O., Buckley, K., Lieberman, L.J. et al. Universal Design for Learning - A framework for inclusion in Outdoor Learning. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 25, 75–89 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-022-00096-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-022-00096-z