Abstract

Our study was design to determine the association between depressive symptoms and mortality in adults over 60 years old Navy Peruvian Veterans. We performed a retrospective cohort study based on a previous cohort study. A total of 1681 patients over 60 years old were included between 2010–2015. Demographic information, self-reported information about falls, physical frailty assessment, tobacco consumption, hypertension, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and was collected. Depression was assessed by the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale. We found that depressive symptoms were present in 24.9% of the participants and 40.5% of them died. Mortality risk in patients with depressive symptoms, physical frailty, and male sex was: RR of 23.1 (95% CI: 11.7–45.7), 3.84 (95% CI: 2.16–6.82), and 1.37 (95% CI: 1.07–1.75) respectively. We concluded that depressive symptoms in Peruvian retired military personnel and their immediate relatives are high and are significatively associated with mortality. Also, being male and frail was associated with an increased risk of death. This reinforces that early detection and assessment of depressive symptoms could be an opportunity to improve the health status of older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Older adult population is constantly growing around the world [1, 31]. In 2019 according to the latest technical report from the United Nations, there were 703 million older adults over 65 years, representing 9.1% of the global population and 56.4 million living in Latin America and the Caribbean. From 1950 to 2020, in Peru, there has been an increase of older adults in 5.7 to 12.4%, respectively [20]. Studies suggest that by 2050 the adult population is expected to rise 120%; however, due to COVID-19 this data will probably change attributable to an excess of mortality rates in this population [3].

According to National Vital Statistics Reports the death rate for the aging population was, 731.9 deaths per 100 000 habitants [14]. Modifiable and non-modifiable factors that predict mortality in the elderly population are depression, hospitalization, cognitive impairment, functional dependence, social isolation, lack of family support, cancer, sex, and age [17]. Therefore, depression affects approximately 17% of the population at some point in life. Epidemiological studies report a prevalence of 5.5 to 12.5% in the geriatric population which increases to 17 to 31% after 65 years [8, 11]. Mental health evaluation including items of the geriatric depression scale have been evaluated in retired military personnel in Latin America, finding a frequency of 42.8% of depressive symptoms [23]. Depression is a widespread, devastating illness considered as a chronic disease with negative consequences since it not only has a high prevalence but also harmful effects on health [1, 10].

Literature suggests the existence of a relationship between depressive symptoms and death, thus S. Saeed Mirza et al., reported that during a 12-year follow-up, people with depressive symptoms had an increased risk of death [24]. Also, people with clinical diagnosis of depression have 1.81 times increased risk of death compared to non-depressed subjects (95% CI: 1.58–2.07) [7]. Furthermore, these studies show that males have a higher risk of death than females, especially in men with severe depression [13, 25].

On the other hand, the use of validated scales in screening, diagnosis, and control of depression symptoms is important to provide appropriate mental care [2, 26]. Some most used screening tests for depression are the Hamilton test, with 92 and 74% of sensitivity and specificity respectively, used for screening of depression in youth, adults, and children. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) is also a commonly used validated screening tool, especially the PHQ-9, with a 91–94% specificity [16]. The 30 items Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was developed in 1982, widely validated, and used; however, shorter versions have been created. In 2001 a Spanish study validated the 5-items GDS version obtaining a sensibility, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 93.1, 73.5, 81.8, and 89.3% respectively [8].

So as to talk about the relationship between mortality and depression, it is important to take into account the confounding factors, as sociodemographic variables and comorbidities that older adults usually have and these would be related to an increase in general mortality such as disability, age, sex, unhealthy behaviors, access to health services, social network and social inequality [5].

The present study is carried out to determine the association between depressive symptoms and death in adults over 60 years old Navy Peruvian Veterans, which will contribute to a better knowledge and assessment in mental health using a screening scale according to the population evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients involved in this study belong to a hospital-based study cohort, and methods have been reported previously [9, 23]. Subjects belonging to the Geriatrics Department of “Centro Médico Naval-Cirujano Mayor Santiago Távara (CEMENA)” (Peruvian Naval Medical Center), were recruited between 2010 and 2015 and followed up in this period. A total of 1681 patients were included and all of them were 60 years or older, all of them retired military personnel and their families. Information was assessed by geriatricians and covered demographic data like sex, age, number of years of education, living status (alone or accompanied), marital status, military rank, and other variables including self-reported history of depression, information about falls, physical frailty, tobacco consumption, hypertension, Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and depressive symptoms. Screening of depression was at baseline enrollment as part of the Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) by the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) short version, consisting of 5 items with a cutoff point of 2/5 which has been previously validated in Spanish-speaking population [8]. Depressive symptoms, in this study, were categorized as a dichotomous variable (presence or absence of symptoms) considering the cutoff point of 2. Physical frailty was evaluated by the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) with a cutoff point of 9/12 [12]. Our dependent variable, mortality, was obtained from the statistics department from CEMENA without taking into count the cause of death. The database was encoded in a Microsoft Excel sheet and then exported to STATA 15.0. Categorical variables were presented in frequencies and percentages, while numerical variables such as median and interquartile range. A Chi-square test was used to compare categorical participant’s characteristics by the presence or absence of symptoms. To compare age by the presence of symptoms, the Mann−Whitney test was performed. Poisson regression was used to provide an estimation of the adjusted Relative Risk (RR) by age, sex, number of years of education, civil status, falls, physical frailty, and living status and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for mortality.

Ethics approval was obtained from “Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas,” a Peruvian school of medicine. We did not report characteristics of identity of patients, they were recognized using codes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

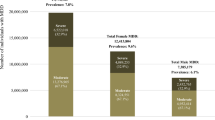

A total of 1681 patients were included, all 60 years or older, 59.49% of them were men, the overall prevalence of physical frailty was 59.37%, a quarter of the total had depressive symptoms (24.99%), and about a tenth of the sample died during the follow-up (10.83%). A total of 16.86% had T2DM, 59.48% hypertension, and 21.24% had COPD. Table 1 shows the detailed prevalence of all socio-demographic characteristics and clinical conditions.

In a bivariate analysis shown in Table 2, we found that 24.46% of patients with physical frailty syndrome have died, compared to 1.5% of patients without it. Also, those patients who presented depressive symptoms died, (40.48%) compared to those who did not present depressive symptoms. The results are presented as Chi2 and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

In order to examine of association between depressive symptoms and death in adults over 60 years of age, crude and adjusted we used the statistical test Poisson regression shown in Table 3. The highest risk of mortality occurred in patients who presented depressive symptoms, were physically frail and male, with a RR of 23.1 (95% CI: 11.7–45.7; p < 0.001), 3.84 (95% CI: 2.16–6.82; p < 0.001) and 1.37 (95% CI: 1.07–1.75; p = 0.010), respectively.

Depressive symptoms and mortality have been studied previously in very specific populations [28]. In Peruvian retired military personnel and their immediate relatives, depressive symptoms, defined by a cutoff point of 2 in the GDS short version, were strongly associated with all-cause mortality in a follow-up period of 5 years and the prevalence rate was almost 25%. Rates of depressive symptoms were higher compared to 10%, found in veteran medical centers in the United States [6], however, patients over 55 years old were included in this study compared to ours. The finding of depressive symptoms in women were more common and is consistent with the higher burden (two-thirds) of depressive symptoms among older women found in one study who aim to determine whether this finding is attributable to sex differences in the onset, persistence, or mortality [4].

In our main finding, depressive symptoms are significatively associated with mortality. Between those who did present symptoms, 40% died compared to 10% who did not present symptoms. In addition, when adjusting these findings to sociodemographic characteristics, there was a high risk of death for those who presented symptoms. As mentioned above, many studies are consistent with this finding, however, when specifically comparing to similar populations, there are some differences. For example, when compared to veterans [6], there is a Hazard Ratio (HR) of 1.81 95% CI: 1.77–1.85 meaning that the risk of death is 1.81 times higher at any point in time. Another study found an HR of 4.15 95% CI: 1.59–10.83 in people over 60 years old in rural China, independently of socioeconomic status. The high RR in our study could be explained by the instrument used, the CGA short version from Yesavage. The 5-item CGA has been validated and compared to the 15-item with a 0.92, 0.83, 0.83, 0.92 and 0.94, 0.81, 0.81, 0.94 for Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) respectively, with a 95% CI in cognitively intact elderly population [22, 30]. This could mean that five-item GDS is as effective as the 15-item GDS for the screening of depression. However, when estimating depression by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) the prevalence is 1–3%, but when assessing it by screening tests, the prevalence is higher (10–27%), overestimating by 10 times the diagnosis [1]. On the other hand, the 5‑item CGA PPV could have been improved in our study due to our appropriate selection strategies, our high-risk population over 60 years old, and the adjusted regression analysis.

Men represented almost 60% of the population and they were found to have a 1.37 higher mortality risk when depressive symptoms were present. Differences between gender mortality have been studied before. In one cohort where authors assessed depressive symptoms and mortality risk factors, they found after an eight years follow-up that mortality risk was detected in men only [29]. Whereas we evaluated all-cause mortality, it is known that men have fewer social circles and with that, they look for help less often, what is more, men tend to commit more suicide than women [15, 21, 27]. Other risk factors well associated with depressive symptoms and mortality are the cerebral and heart ischemia diseases [15, 27, 28]. In our study we included retired veterans and their immediate family, veterans are mostly men so that could not be extrapolated in a general population.

Physical frailty was also evaluated in our study, reporting a frequency of 24% in participants who died during the follow-up, compared to 1.5% between those who did not, giving a 3.84 times risk of dying in depressed old people. This becomes important because leads us to explain depressive symptoms related to death, because of the concurrent presence of physical frailty within this elderly population. However, it is well known that physical frailty by itself is associated with high mortality risk [19]. A.G. Soloviev et al. in their review concludes that depressive symptoms assessment is an important matter in the evaluation of the emotional sphere in older adults [27] and psychological assessment in this population should be assessed considering social and gender aspects [18].

There are certain limitations that should be mentioned. Although our participant’s characteristics are common in the elderly population, we can not necessarily compare them with the general population because we included retired veterans and their immediate relatives, therefore our veterans had not been exposed to any war or conflict, so the risk of PTSD is low. Second, patients were recruited from ambulatory levels of this tertiary hospital care, meaning that they probably presented comorbid diseases. Third, we assessed depressive symptoms, with no somatic disease evaluation at baseline without a follow-up so we do not certainly know whether they received the final diagnosis of depressive symptoms leading to an overestimation of the results, however, our large sample size could partially compensate for these limitations. Fourth tobacco consumption was assessed by medical history and not using an index.

CONCLUSIONS

Depressive symptoms frequency in Peruvian retired military personnel and their immediate relatives had a high frequency and are significatively associated with mortality. Being male, single, and physically frail is associated with an increased risk of death when depressive symptoms are present. These findings reinforce that early detection and assessment of depressive symptoms could be an opportunity to improve the health status of older adults, and further research could purpose interventions to decrease the impact of mental health on mortality in the elderly population.

REFERENCES

Aguilar-Navarro, S. and Ávila-Funesa, J.A., La depresión: particularidades clínicas y consecuencias en el adulto mayor, Gac. Med. Mex., 2007, vol. 143, no. 2, pp. 141–148.

Anderson, J., Michalak, E., and Lam, R., Depression in primary care: tools for screening, diagnosis, and measuring response to treatment, Br. Columb. Med. J., 2002, vol. 44, no. 8, pp. 415–419.

Banerjee, A., Pasea, L., Harris, S., et al., Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study, Lancet, 2020, vol. 395, no. 10238, pp. 1715–1725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0

Barry, L.C., Allore, H.G., Guo, Z., et al., Higher burden of depression among older women: the effect of onset, persistence, and mortality over time, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 2008, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.17

Brandão, D.J., Fontenelle, L.F., Da Silva, S.A., et al., Depression and excess mortality in the elderly living in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis, Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry, 2019, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5008

Byers, A.L., Covinsky, K.E., Barnes, D.E., and Yaffe, K., Dysthymia and depression increase risk of dementia and mortality among older veterans, Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry, 2012, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 664–672. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822001c1

Cuijpers, P. and Smit, F., Excess mortality in depression: a meta-analysis of community studies, J. Affect. Disord., 2002, vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00413-x

Del Valle, R.D.D., Sánchez, A.H., Cano, L.R., and Jentoft, A.C., Validación de una versión de cinco ítems de la Escala de Depresión Geriátrica de Yesavage en población española, Rev. Españ. Geriatr. Gerontol., 2001, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 276–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0211-139X(01)74736-1

Díaz-Villegas, G., Parodi, J., Merino-Taboada, A., et al., Calf circumference and risk of falls among Peruvian older adults, Eur. Geriatr. Med., 2016, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 543–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurger.2016.01.005

Duman, R.S., Pathophysiology of depression and innovative treatments: remodeling glutamatergic synaptic connections, Dialogues Clin. Neurosci., 2014, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 11–27. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.1/rduman

Gálvez, V., Ho, K.A., Alonzo, A., et al., Neuromodulation therapies for geriatric depression, Curr. Psychiatry Rep., 2015, vol. 17, no. 7, p. 59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0592-y

Gómez, J.F., Curcio, C.-L., Alvarado, B., et al., Validity and reliability of the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): a pilot study on mobility in the Colombian Andes, Colomb. Med., 2013, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 165–171.

Holwerda, T.J., van Tilburg, T.G., Deeg, D.J., et al., Impact of loneliness and depression on mortality: results from the Longitudinal Ageing Study Amsterdam, Br. J. Psychiatry, 2016, vol. 209, no. 2, pp. 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.168005

Kochanek, K., Murphy, S., Xu, J., and Arias, E., Deaths: final data for 2017, Nat. Vital Stat. Rep., 2019, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1049–1056.

Li, X., Xiao, Z., and Xiao, S., Suicide among the elderly in mainland China, Psychogeriatrics, 2009, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-8301.2009.00269.x

Maurer, D.M., Raymond, T.J., and Davis, B.N., Depression: screening and diagnosis, Am. Fam. Phys., 2018, vol. 98, no. 8, pp. 508–515.

Maia, F.O., Duarte, Y.A., Lebrão, M.L., and Santos, J.L., Risk factors for mortality among elderly people, Rev. Saude Publ., 2006, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1049–1056. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102006005000009

Miakotnykh, V.S., Sidenkova, A.P., Borovkova, T.A., and Berezina, D.A., Medical, psychological, social and gender aspects of aging in modern Russia, Adv. Gerontol., 2014, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 302–309.

Mitnitski, A., Song, X., Skoog, I., et al., Relative fitness and frailty of elderly men and women in developed countries and their relationship with mortality, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc., 2005, vol. 53, no. 12, pp. 2184–2189.

World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights, Geneva: World Health Org., 2019.

Park, S.H., Kim, D., Cho, J., et al., Depressive symptoms and all-cause mortality in Korean older adults: a 3-year population-based prospective study, Geriatr. Gerontol. Int., 2018, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 950–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13270

Rinaldi, P., Mecocci, P., Benedetti, C., et al., Validation of the five-item geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in three different settings, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc., 2003, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 694–698. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00216.x

Runzer-Colmenares, F.M., Samper-Ternent, R., Al Snih, S., et al., Prevalence and factors associated with frailty among Peruvian older adults, Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr., 2014, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2013.07.005

Saeed Mirza, S., Ikram, M.A., Freak-Poli, R., et al., 12 year trajectories of depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults and the subsequent risk of death over 13 years, J. Gerontol., Ser. A, 2018, vol. 73, no. 6, pp. 820–827. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx215

Schoevers, R.A., Geerlings, M.I., Beekman, A.T., et al., Association of depression and gender with mortality in old age: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL), Br. J. Psychiatry, 2000, vol. 177, no. 4, pp. 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.4.336

Sonnenberg, C.M., Deeg, D.J., van Tilburg, T.G., et al., Gender differences in the relation between depression and social support in later life, Int. Psychogeriatr., 2013, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212001202

Soloviev, A.G., Popov, V.V., and Novikova, I.A., Diagnosis of disorders of the emotional sphere in older persons, Adv. Gerontol., 2016, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079057016030140

Sun, W., Schooling, C.M., Chan, W.M., et al., The association between depressive symptoms and mortality among Chinese elderly: a Hong Kong cohort study, J. Gerontol. Ser. A, 2011, vol. 66, no. 4, pp. 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glq206

Teng, P.-R., Yeh, C.-J., Lee, M.-C., et al., Depressive symptoms as an independent risk factor for mortality in elderly persons: results of a national longitudinal study, Aging Mental Health, 2013, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.747081

Trevethan, R., Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values: foundations, pliabilities, and pitfalls in research and practice, Front. Publ. Health, 2017, vol. 5, no. 5, p. 307. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00307

World Report on Ageing and Health, Geneva: World Health Org., 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.Statement on the welfare of humans. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines were followed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Astorga-Aliaga, A., Díaz-Arroyo, F., Carreazo, N.Y. et al. Depression Symptoms and Mortality in Elderly Peruvian Navy Veterans: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Adv Gerontol 12, 56–62 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079057022010039

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079057022010039