The Ludocreative Expression for the Production of Texts in Children of Early Education

The Ludocreative Expression for the Production of Texts in Children of Early Education

Volume 5, Issue 5, Page No 127-136, 2020

Author’s Name: Giuliana Gaona-Gamarra1, Brian Meneses-Claudio2,a), Avid Roman-Gonzalez2

View Affiliations

1Faculty of Humanities Education and Social Sciences, Universidad de Ciencias y Humanidades, Lima, 15314, Perú

2Image Processing Research Laboratory (INTI-Lab), Universidad de Ciencias y Humanidades, Lima, 15314, Perú

a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: bmeneses@uch.edu.pe

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 5(5), 127-136 (2020); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj050518

DOI: 10.25046/aj050518

Keywords: Texts’ Production, Ludocreative Expression, 5-year-old Children, Improving Scores, Evaluation to Children

Export Citations

The text’s production carried out in this research aimed to 5-year-old children from the IE 555 Inmaculada Concepción, under the modality dictated to adult, had a design and application of 22 sessions during three months with the experimental group. On their methodological approach was based on the expression ludocreative, articulating the written experience jointly with the art expression in the pedagogical fields of plastic, musical, scenography and corporal expression, propitiating the children´s prominence through a playful tone with deductive situations in the learning processes. For this, a quasi-experimental design was considered, with a control group of 15 children and an experimental group of 20 children. After selecting the groups in an intentional non-probabilistic manner, the questionnaire was applied to assess the production of texts to the respective groups. The results indicate the effect of the application of the proposal. This could be evidenced in the establishment of differences in the pre-test and post-test of both groups, and differences in the scores between both groups. In particular, it was found that the difference between pre and post-test was greater in the experimental group, obtaining a fundamental achievement to continue deepening in this playful and creative within the framework of pedagogical innovation.

Received: 13 July 2020, Accepted: 14 August 2020, Published Online: 09 September 2020

1. Introduction

The ludocreative expression has as a main purpose to develop a subject from its own cultural environment, affirming its identity, without the induction of predetermined models with the aim of highlighting the role of doing and feeling in order to learn and think.

The research presented in [1], it mentions that ” To learn to think, it is necessary to exercise our limbs, our senses, our organs, which are the instruments of our intelligence”. The creativity links with various experiences that invite to the symbolic imaginary from the interactions of the subject-objects-subjects through the dimensions of plastic, musical, corporal, scenography and cultural expression, which give new transformative perspectives since they articulate aesthetic and cognitive values for the systematization of new concepts [2].

The research presented in [3], this research consists of a playful strategies action plan that aims to develop oral expression skills and abilities in 4-year-old children at the early education level. Due to the problem that was found in them, the low level of oral expression evidencing in practice, the little participation and initiative to express themselves, pronounce words, sounds and ability to express themselves. To validate this research work, the hypothesis to defend is the action plan “Dilo Jugando” is developed and applied, based on the development of playful strategies, then they will significantly increase oral expression in 4-year-old boys and girls. from the early education level of the kindergarten 1861 –October 9– Huamachuco Sánchez Carrión in 2015, based on the theories as in [4] by Piaget and Vygotsky and the playful strategies of Raimundo Dinello. The results obtained in the application of the action plan based on the development of recreational strategies, significantly demonstrate the solution to the problem, achieving a significant increase in the level of oral expression. These skills helped children to achieve better oral expression in the abilities and skills to express themselves, pronounce words, develop phonology, syntax, semantics, speaking, listening, and self-expression and learning.

The research presented in [5], this research responds to a qualitative-quantitative approach, since, for the analysis of the information and its subsequent organization, techniques were applied that allowed detailing the strategies used by the teacher in the classroom for the development of the oral language. The research work modality is socio-educational and due to the depth level, it is correlational descriptive in order to determine the relationship between both variables, for which the Pearson Correlation Coefficient was applied, which is 0.63. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient allowed a reliability of 0.84 to be obtained in the observation sheet and in the questionnaire with a reliability of 0.85. As conclusions, it was found that most teachers do not apply ludocreative strategies for oral development. And finally, a proposal of activities framed in the dimensions is made: linguistic games, dramatic games and the traveling story, carried out through play and playful as an integrating element of learning. Among its results, it can be affirmed that ludocreative strategies could help in the development of oral language in children of the Early Education Sub level.

The research presented in [6], this research developed a research work entitled: “Producing texts at the beginning of schooling: the production of oral texts, dictated to an adult and written, in the 5th and 1st grade room. Comparison between different pedagogical approached”. This comparative study refers to the knowledge of the written language that children of these ages. They relate the knowledge made by them with the type of teaching proposals. Among the results, the children’s narrative capacity was evidenced from their different levels of construction of the conventional writing system, the ability to produce oral, dictated and written texts, and knowledge of the narrative genre. Likewise, differences in textual production were observed in two teaching contexts (formal and constructivist); demonstrating greater achievements in children’s learning in the constructivist approach.

The research presented in [1], it mentioned in his book “Emilio o la Educación”, that in order to learn to think it is necessary to exercise our limbs, our senses, our organs, which are the instruments of our intelligence. That is why the game that etymologically means free movement, is the essence that leads to this immediate pleasure and joy that engages children in the development of all their abilities.

Dinello and Huizinga cited by [7] states that playful is not limited to the game or vice versa since playful is a much more complex concept that encompasses the man in its entirety. The playful activity dynamizes the educational processes of childhood, since it allows creating significant scenarios for the development of competence in a comprehensive and harmonious way. Those gratifying experiences for human development are linked in turn with creativity through various experiences that invite to the symbolic imaginary with the interactions of the subject-objects-subjects. In the ludocreative expression, the following pedagogical fields are considered through areas of expression related to the arts: plastic expression, musical expression, body expression, scenography expression and the area of cultural initiation, which allow new transformative perspectives since they articulate aesthetic and cognitive values for the systematization of new concepts. As [8] affirms, articulation is a possibility of transforming cognitive acquisitions and emotional states into different domains of thought and application possibilities, since an evolution of the imaginary and understanding of the symbolism of expression is evident.

In Chapter II, the materials and methodology used to carry out the study, the hypotheses and variables, as well as the distribution of the population and sample, based on certain criteria; data collection and processing techniques are also pointed out. In chapter III, the results and analysis are presented (it is consolidated with the psychometric analysis of the instrument used and the processing and analysis of the results through inferential statistics, in such a way that it evidences the aspects of measurement and impact of the object program of this research). In chapter IV, the discussions of the research are shown, also the revalidation of the results shown in the research work. Finally, in chapter V, conclusions and some recommendations on the results obtained through the application of the sessions developed with the children in the applied program are presented, which can be a reference for the development of future research in this area.

2. Methodology

This research has been carried out to improve the production of texts in 5-year-old children from IEI 555 Inmaculada Concepción, based on the teaching-learning methodology of the ludocreative expression.

This practice promoted the development of text production, with respect to planning, textualization, and revision in messages, stories, riddles, poetry.

In this way, the children during the planning organized their ideas about the type of text and its purpose, in the textualization, they created the information, through the modality dictated to an adult, and in the revision a rereading was made to make the improvements, through the opinion and the exchange of ideas.

Subsequently, once the proposal was completed, the publication of their creations in craft books was made, taking into account his drawings and a spontaneous writing of lines and graphics, being located in the library sector.

Regarding the context, it should be noted that I.E.I. N° 555 Inmaculada Concepción is located in the Santiago de Surco district, province and department of Lima. The geographical scope corresponds to the urban area. The I.E.I. has a morning and afternoon shift. The afternoon shift was considered for the present research, with a sample of 22 children, whose age ranges are from 5 to 6 years old.

For the evaluation of the children’s progress, a questionnaire was made that was completed by the teacher in charge of the group, in addition to determining an evaluation range for them.

2.1. Population and Sample

The population consisted of 210 students from the institutions distributed in 4 classrooms on morning and afternoon shifts, respectively. It should be noted that educational institutions are state, of medium socioeconomic level from the Santiago de Surco district, UGEL 07.

The sample was consisted of 20 children of both sexes in the experimental group of IEI 555 Inmaculada Concepción and the control group was made up of 15 children of both sexes of IEI Nuestra Señora del Carmen, all with an early level of education between 5 and 6 years old.

For this, inclusion criteria were taken into account considering the evolutionary development of children according to their age, considered in the respective checklist, as well as the permanence of attendance at the learning sessions, in terms of the exclusion criteria, it should be noted that the sample did not take into account children under 5 years old and with special educational needs.

2.2. Evaluation Criteria

For the application of the text production assessment questionnaire, some basic conditions regarding the arrangement of the environment were envisaged, ensuring that it is comfortable, illuminated and without major distractions for the child. In addition, the necessary material for the completion of the questionnaire was previously organized, such as: sheets, notebook, pencil, pen, six images in sequence to be organized freely by the children for the story creation, an apple for the assessment of the riddle creation area and a flower puppet for the creation of poetry.

Before starting with the questionnaire, an atmosphere of relaxation and trust was provided to the children, in order to facilitate interaction with each one, making a motivating activity.

In addition, some evaluation criteria were defined to provide a preliminary result for each of the variables of the text production. These were the criteria:

- Clarity (C): It is written in appropriate and precise language.

- Performance (P): It is adequate, useful, consistent, appropriate or relevant according to its purpose and function.

- Sufficiency (S): The items are sufficient per analysis factor.

- Objectivity (O): It is in accordance with the proposed objectives.

To generate the statistics and verify the development of the control and experimental population, a scoring system was created following certain criteria, these are the following with their corresponding scores:

- Excellent (4): Evaluation criteria are met.

- Good (3): Meets the criteria, needs minimal modifications.

- Regular (2): Meets the criteria, needs major modifications.

- Poor (1): The evaluation criteria are not met.

The evaluation was carried out independently for each child based on his/her progress and development of the different activities proposed.

2.3. Text Production Questionnaires

The assessment questionnaire is made up of 4 subtests, whose total score is 24 points and whose 16 items are distributed as follows:

Text Production Steps with a total of 8 items, as shown in Table 1: Planning (PL) 3 items, textualization (T) 1 item, revision (R) 1 item, publication (P) 1 item; whose general value obtained is 8 points.

Types of literary texts with a total score of 6 points, having 4 items, as shown in Table 2: Story creation: planning (PL) and textualization (T) 2 items, revision (R) 2 items.

Table 1: Text Production Steps Evaluation Chart (English Version)

| I. STEPS IN THE PRODUCTION OF TEXTS | CRITERIA | |||

| C | P | S | O | |

| PLANNING (PL) The teacher writes verbatim what the child says | ||||

| 1 a. Who would you like to write to? | ||||

| 1 b. What would you like to write to him or her? | ||||

| 1 c. What would you write to him or her for? | ||||

| TEXTUALIZATION (T) The teacher writes verbatim what the child says | ||||

| 2 a. What is the message you want to communicate? (Thank him or her, make an order, or another.) | ||||

| REVISION (R) The teacher reads the text produced for the child to decide whether or not he or she wants to modify it. | ||||

| 3 a. Do we leave the message like that or would you change it? | ||||

| PUBLICATION (P) The teacher writes verbatim what the child says. If the child has the initiative to produce another presentation of the text, they are provided with consumable materials (colors, sheets, stickers.) | ||||

| 4 a. How will you get this message to “x”? (friend, parents or another person) | ||||

Table 2: Story Creation Evaluation Chart (English Version)

| II. TYPE OF TEXTS: LITERARY | CRITERIA | |||

| C | P | S | O | |

| A. STORY CREATION The teacher presents six images; the child organizes them and creates a story. The teacher copies verbatim what the child says. |

||||

| PLANNING (PL) AND TEXTUALIZATION (T) | ||||

| 1. How would you create a story from these images? | ||||

| 2. What title would you give it? | ||||

| REVISION (R) | ||||

| 3. Would you change any part of the story? | ||||

| If the answer is yes: 4. Which one? |

||||

Creation of a riddle with a total score of 5 points, having 3 items, as shown in Table 3: Planning (PL) and textualization (T) 1 item, revision (R) 2 items.

Table 3: Riddle Creation Evaluation Chart (English Version)

| B. CREATION OF RIDDLE | CRITERIA | |||

| C | P | S | O | |

| PLANNING (PL) AND TEXTUALIZATION (T) | ||||

| 1. How would you create a riddle from this object? | ||||

| REVISION (R) | ||||

| 2. Would you change any part of the riddle? | ||||

| If the answer is yes: 3. Which one? |

||||

Poetry Creation with the total score of 5 points, having 3 items, as shown in Table 4: Planning (PL) and textualization (T) 1 item, revision (R) 2 items.

Table 4: Poetry Creation Evaluation Chart (English Version)

| C. POETRY CREATION | CRITERIA | |||

| C | P | S | O | |

| PLANNING (PL) AND TEXTUALIZATION (T) | ||||

| 1. How would you create poetry for this puppet? | ||||

| REVISION (R) | ||||

| 2. Would you change any part of the poetry? | ||||

| If the answer is yes: 3. Which one? |

||||

The 16 items correctly resolved in the four corresponding sections, were organized with the total results.

2.4. Data Collection

The text production test mentioned above was applied to the experimental group, before and after the experiment carried out (Teaching module – Create and Have Fun based on the ludocreative expression). Likewise, the same test was carried out on the control group, to measure if the level of text production in both groups was similar or if there were differences.

It is worth mentioning that the application of the interview was semi structured, since it was adapted to the children through the questionnaire, which, although there were pre-established questions, were interspersed with some of the open type during the dialogue with the children. The interview was conducted in a quiet and neutral place in the I.E.I. (the office and / or library of the Inmaculada Concepción educational center were organized to be a relax place for children). In the case of the control group, it was carried out in a neutral place in the classroom, which the other children did not have access to, and on some other occasions in the management office.

The “Create and Have Fun” module has 22 learning sessions and are designed to achieve a text production competition. They were carried out between 2 to 3 times per week in an approximate time of 50 minutes, between the months of June to September of the year 2017, taking into account the proposal of the ludocreative expression. [9]

For the development of the learning sessions, the suggested materials and spaces in the classroom, a psychomotor environment, a library environment and a playground were organized.

Both group and individual activities were carried out with the support of the classroom tutor and an assistant to carry out each of the sessions.

It worked through processes, the first being the Playful Introduction, as shown in Figure 1, beginning with an initial game where children are required to move around the classroom, thus recognizing their environment and their classmates.

Figure 1: Beginning Movement Game

It is about the children trying to produce texts through their memories and imagination of the situations that they have gone through. In session 9, it was called “Our best vacation times” where they dramatized an imaginary trip, as well as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Dramatic Representation Expression simulating an Imaginary Trip

The next step is to do the experimentation, being the group textualization with children’s drawings, as seen in Figure 3; this step requires a bit more time because it is a real-time capture of children’s ideas. As can be seen in Figure 3, children are required to work as a group in order to speed up and also create complementary stories and ideas.

Figure 3: Group Textualization with Children’s Drawings

At the end of the session, a plenary was held to observe the different productions, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Revision: Plenary of the Creations made

On the other hand, at the end of the pedagogical proposal, the children in the environment of the library of the Educational Institution listened to the oral narration of some of their productions and later, these were located in the library sector of the classroom, this helps the children look their text productions and the progress of their works, some examples of these works were books, drawing and compositions as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Group and Individual Book and Composition of Rhymes

3. Results

The purpose of this research was to determine how the design and application of the methodological proposal based on the ludocreative expression influences the production of texts and each of its planning, textualization and revision aspects, by 5-year-old children. For this, various experiences were carried out in which the studied group participated in playful situations in different learning fields.

The results of the statistical analysis revealed that before developing the intervention, the performance of children in both the control group (Nuestra Señora del Carmen) and the ex-experimental group (Inmaculada Concepción) in the evaluated steps of text production, such as: planning, textualization and revision in its different types: message, story, riddle and poetry, it was equivalent and therefore its performance was similar with which these could be subjected to subsequent comparisons. In this sense, it was found that the groups had a different performance related to the type of intervention they received (intervention of the ludocreative expression methodology and non-intervention), as can be seen in Table 5 and Table 6 (Shapiro Wilk Test) the results obtained from the Entrance and Exit tests.

| Description | Group | Statistic | Gl | p value |

| Text Production | Control | 0.965 | 15 | 0.776* |

| Experimental | 0.892 | 20 | 0.03** | |

| Planning | Control | 0.949 | 15 | 0.505* |

| Experimental | 0.903 | 20 | 0.047** | |

| Textualization | Control | 0.905 | 15 | 0.114* |

| Experimental | 0.955 | 20 | 0.457** | |

| Revision | Control | 0.499 | 15 | 0.000** |

| Experimental | 0.672 | 20 | 0.000** |

Table 5: Shapiro Wilk Test for Entrance Test Scores

*P > 0.05; **P < 0.05

The results of the Shapiro Wilk normality test allow to establish that in the control group the scores for text production, planning and textualization fit a normal distribution (p>0.05) and the revision score does not fit a distribution normal (p<0.05), while in the experimental group the text production, planning and revision scores do not fit a normal distribution (p<0.05) and the textualization score fits a normal distribution (p>0.05).

Table 6: Shapiro Wilk Test for Exit Test Scores

| Description | Group | Statistic | Gl | p value |

| Text Production | Control | 0.848 | 15 | 0.016** |

| Experimental | 0.929 | 20 | 0.148* | |

| Planning | Control | 0.864 | 15 | 0.028** |

| Experimental | 0.887 | 20 | 0.024** | |

| Textualization | Control | 0.906 | 15 | 0.116* |

| Experimental | 0.857 | 20 | 0.007** | |

| Revision | Control | 0.499 | 15 | 0.000** |

| Experimental | 0.803 | 20 | 0.001** |

*P > 0.05; **P < 0.05

The results of the Shapiro Wilk normality test allow to establish that in the control group the scores for text production, planning and revision do not fit a normal distribution (p<0.05) and the textualization score fits a distribution normal (p>0.05), while in the experimental group the planning, textualization and revision scores do not fit a normal distribution (p<0.05) and the text production score fits a normal distribution (p>0.05).

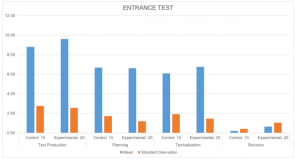

Through of the preliminary data obtained, the mean and standard deviation of the Entrance Test and the Exit Test were evaluated in both Control and Experimental cases, these results are shown in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7: Mean and Standard Deviation of the Entrance Test

| Description | Group | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| Text Production | Control | 8.80 | 2.76 |

| Experimental | 9.60 | 2.56 | |

| Planning | Control | 6.67 | 1.72 |

| Experimental | 6.60 | 1.19 | |

| Textualization | Control | 6.07 | 1.91 |

| Experimental | 6.75 | 1.45 | |

| Revision | Control | 0.20 | 0.41 |

| Experimental | 0.65 | 1.04 |

Note: Control = 15, Experimental = 20

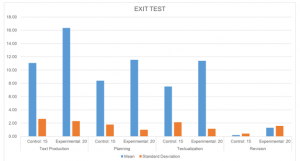

Table 8: Mean and Standard Deviation of the Exit Test

| Description | Group | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| Text Production | Control | 11.07 | 2.63 |

| Experimental | 16.35 | 2.30 | |

| Planning | Control | 8.40 | 1.77 |

| Experimental | 11.55 | 1.00 | |

| Textualization | Control | 7.53 | 2.13 |

| Experimental | 11.40 | 1.14 | |

| Revision | Control | 0.20 | 0.41 |

| Experimental | 1.30 | 1.59 |

Note: Control = 15, Experimental = 20

In the exit test of the text production, the results demonstrate the effect of the methodological proposal based on ludocreative expression in the 5-year-old children of IEI Inmaculada Concepción, who have gradually become familiar with it, where their productions were accompanied by images (drawings, collage, paintings of different types) of shorts dramatizations (role plays, puppet play, symbolic representations, motor games, body expression) and musical games. It is observed that these experiences allowed them to learn to discover, recognize and in some cases, to use the signs of written language, the need arose to decipher the medium, to appropriate its signs [10]. Which is a good indicator since it sees that this process has opened up the possibility of free expression, exchange and contrast of ideas with their classmates, presenting an investigative attitude, curiosity about their surroundings, respect for their own achievements and those of others.

It should be noted that at first, there were no greater notions about some types of productions such as the use of poetry, riddles and tongue twisters, compared to the stories or messages which they were more used. Therefore, it deserves that these fields can be deepened and developed specifically and/or with a longer application time for better effects.

It can be verified that the scores presented by the experimental group demonstrate a considerable improvement in their performance as a result of the pedagogical intervention through the proposal of the methodology of ludocreative expression. And this was significantly higher than the performance presented by the control group. So, it can be affirmed that the purpose of this research has allowed, offering children the opportunity to experience, discover, shape their expectations on their own initiative, in order to develop their potential, develop own thinking and creative attitudes in dialogue with their classmates and those who have accompanied this exchange process through the proposal. There is no doubt that in this interim search is to recognize in each child a subject of expression and creation, so that it is recognized in its existence and in its possibilities of learning. Furthermore, being familiar with creativity, they affirm themselves in flexibility, spontaneity and originality, qualities that [11] mentions, they are necessary to insert themselves in a questioning way in a world characterized by the sense of efficiency and utility.

Creating an environment conducive to continued discovery [10] has been quite an assumed challenge, since it fosters open situations, an unusual situation in the classroom, since children are often used to following instructions and indications, often biasing their own initiatives or proposals, this methodology has allowed to open gaps to be considered as protagonists, discovering playful experiences and interacting with their classmates and materials. In addition, it has had the support of the teacher and classroom assistant who accompanied this process with their active participation through dialogues, questions, contributions of information, and openness to the various forms of art expression (painting, modeling, body expression, music, dramatization, building) to finally systematize children’s opinions towards the objective to be achieved about the different types of text productions (messages, poetry, stories, riddles, among others) as stated by [8] the child with its fantasy, by imitation, begins to understand and use the symbols of communication that later allows him or her to consolidate a conceptual elaboration., in this case through the verbalization of the various texts that the child formulates, learning takes place with a natural sequence, which makes from curiosity to understanding. On the other hand, it should be noted that children concluded this process of text production with the craft publication of their own books, which, according to [11], enables an aesthetic perception and a physical relationship from the tactile, visual and olfactory aspects. Consequently, from the perspective of Education through Art, expression rather than a successful product is a process, which is coupled with respect to the identity and culture.

The results of the statistical analysis allow to verify that the application of the teaching-learning methodology based on the pedagogy of ludocreative expression significantly improves this aspect, where the children of the experimental group (Inmaculada Concepción) get a higher score in the production of texts compared to the children of the control group (Nuestra Señora del Carmen), demonstrating that the planning of the texts by the 5-year-old children of IEI 555 Inmaculada Concepción in the district of Santiago de Surco significantly improves compared to IEI 086 Nuestra Señora del Carmen from the Santiago de Surco district, for this, the children participated through expression activities so that from that experience, they prepared to tell their emotions and ideas about themselves and the environment, intuitively using various techniques and materials, as stated by [12] thus giving the aspect of planning that answer the questions like: Who would you like to like to send this “x” (message, story, poetry) to? thus determining the recipient, what do I want to express? and why?, thus focusing on the subject and the purpose. From this perspective, the contributions of the ideas of the children that worked individually and in groups are visualized, contributions that can be sustained in a group debate through dialogue.

Regarding the textualization as shown in Table 8, the teaching-learning methodology based on the pedagogy of ludocreative expression significantly improves the textualization by 5-year-old children of IE 555 Inmaculada Concepción in the district of Santiago de Surco. In relation to this [13], points out that the expression of the narrative qualities makes mention of the attitudes towards the reproduction of information, demonstrating the rhetorical qualities of children in which they express their needs, emotions, interests, ideas and experiences using sentences understandable to others, varying the intonation according to their intention; organizing their ideas and asking what they did not understand, participating in oral communication situations, generally focusing on the subject and interpreting what other people say, identifying explicit information and making deductions, they also enjoy listening to texts of simple structure in which known words predominate and relate what was heard in their own words, the latter is evidenced in group productions.

In the production of texts, the revision that can see the effects achieved in the experimental group (Inmaculada Concepción) obtain a higher score although differences that are not significant with respect to the children in the control group (Nuestra Señora del Carmen) which it can be verified that the application of the teaching-learning methodology based on the ludocreative expression improves the revision of the production of texts by children of 5 years of age, although to a lesser degree compared to the other aspects of planning and textualization. In this sense, these data indicate that there were certain difficulties at the time of applying this aspect, due to it requires a more detailed evaluation, especially if it is developed individually. According to the approaches made by [13], it has to be analyzed from a perspective in which the study of the psychological and pedagogical conditions of learning are basic to understand the results of literacy and the results are important to understand the differences, precisely in the revision, particularities are observed in which more precise models of the processing and understanding of what is written must be reached, going beyond the description of interesting evolutionary situations. For this, the role of metacognition must be reevaluated by providing precise questions that allow them to question children about their own productions, originating a dialogue to contrast their initial hypotheses with new ideas that emerge from the rereading, based on this, the scope mechanism should be rethought to improve this process, also considering that the level of metacognition in 5-year-old children will go evolving as they grow and that is evident in “children’s awareness of their purpose in reading, how to proceed to achieve those purposes and how to regulate the process through self-regulation of understanding. Metacognition is applied to reading when one is aware of the behavior during reading and the appropriate use of reading strategies to facilitate or remedy failures during its execution” [14].

Figure 6: Bar Graph of the Mean and Standard Deviation of the Entrance Test

Figure 7: Bar Diagram of the Mean and Standard Deviation of the Exit Test.

The need for an explanation of individual differences both in excellence and regarding to difficulty cannot be ignored, in this sense it can be seen that children have proven to be so constructive in relation to writing and written language, starting with the orality, they have also become familiar with the different types of texts, recognizing their structure and particularities, so it should be perceived that after textualization, this aspect can be deepened in a particular way depending on what the child want communicate, remaining the main idea, identifying the repetitions or omissions, being necessary to promote other alternatives of mediation scope of work in the classroom and that can also be extended at home. On the other hand, it coincides with the proposal developed by [15] when he mentions that in the revision, the text is refined, and in which it would be convenient to verify or reject the existence of any difficulty, since in the case of children, it observes that several of them are in the process of making coherent texts both in the content and in the structure of the same, and there have also been cases in which children have not required to use this revision process because they have responded to their true intentions, in this sense, are varied communicative situations.

Finally, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the bar graph of the mean and standard deviation of the entrance test and the exit test, respectively. It should be noted that in these diagrams the difference between the results of the control and experimental groups can be seen more clearly.

4. Discussion

This research confirms the importance of promoting playful activities to generate the production of texts in children, allowing to stimulate, develop and enrich the potential of oral and written language.

The application of the ludocreative expression methodology allowed the enrichment of the components of text production (messages, poetry, stories, riddles) in the children from IE 555 Inmaculada Concepción.

Text production is significantly increased by natural development, as was the case in the control group. However, after applying the ludocreative expression methodology, it was observed that almost all of the children exposed to it managed to achieve superior performance in the use of its components, considering the respective steps in the production of texts. As well as, statistically significant differences are shown before and after the application of the program in the experimental group.

Likewise, there are statistically significant differences in the children of the experimental group compared to the children of the control group, which is possible to visualize the effects of the activities of ludocreative expression in relation to the children belonging to the experimental group.

5. Conclusions

The application of the teaching-learning methodology based on the ludocreative expression significantly improves the production of texts, where it is evident that the control group obtained a score of 9.53 while the experimental group reached 24.35. Based on those results, the effect of the ” Create and Have Fun” module is demonstrated.

Regarding planning, the control group has a score of 9.83, while the experimental group is 24.13, which shows a significant improvement in 5-year-old children from IE 555 Inmaculada Concepción compared to IE 086 Nuestra Señora del Carmen from the Santiago de Surco district.

Regarding textualization, the control group presents a score of 9.60, while the experimental group is 24.3, which shows that the experimental group has a greater and significant increase in relation to the control group.

The application of the teaching-learning methodology based on the ludocreative expression does not significantly improve the revision, which shows an average range of 14.20 in the control group, while in the experimental group a 20.85 is shown, which shows that it is necessary to implement this dimension to get better results.

The importance of new forms of teaching is important in Peru and is highlighted when it comes to children. Currently, the Ludocreativa education has been applied in few educational institutions in Peru, that is why in this study, the importance of applying this methodology will be corroborated, it would improve teaching in children in the majority and also that it would enhance their imagination. In this research work, the difference between the control and experimental groups is shown, as a conclusion there is a significant difference between the entrance and exit tests in the production of texts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

We want to thanks to Dr. Raimundo Dinello, who opened up the possibility of growth on a personal and professional level through each of the exchanges of the ludocreative forums.

Also, we would like to thank IE 555 Inmaculada Concepción and IE 086 Nuestra Señora del Carmen, who, through their managers and teaching staff provided the best of logistical and pedagogical provisions for the implementation of this research.

- M. Izquierdo, Emilio o la educación (Rouseauu, trans), Editorial Verbum, 2019.

- L. Echavarría, Y. Rivera, and M. Segovia, “Ludoteca: Villa Kids. For the development of social skills of children from 4 to 7 years old at Colegio Gimnasio Moderno Villa del Norte,” Bachellor Thesis, Universidad de Cartagena, 2016.

- M. Villena, “Action Plan “Create and Have Fun“ based on playful strategies to raise the level of oral expression in 4-year-old children from J.N. N° 1861- 9 de Octubre, Huamachuco Sánchez Carrión in the 2015,” Magister Thesis, Universidad Nacional Pedro Ruiz Gallo, 2019.

- J. Piaget, B. Inhelder, Psicología del niño, Ediciones Morata, 2016.

- R. Pacheco, D. Mafla, “Ludo-creative strategies in the development of the oral language of girls and boys of the kirdengarten level 2 (3-4 years) of the child development center ‘My Golden World Kids’ in the period 2017 – 2018,” Ph.D Thesis, Universidad Central de Ecuador, 2017.

- G. Zuccalá, “Producing texts at the beginning of schooling: the production of oral texts, dictated to an adult and written, in the 5th and 1st grade room. Comparison between different pedagogical approaches,” Bachellor Thesis, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, 2015.

- E. L. Escalante, M. Coronell, V. Narváez-Goenaga, Juego y lenguajes expresivos en la primera infancia una perspectiva de derechos, Editorial Verbum, 2016.

- R. A. Dinello, Cuaderno de lúdica y sociología de la educación, Psicolibros Waslala, 2011.

- K. M. Silgado, L. C. Rey, “Improving reading comprehension through recreational activities in second grade students of the Nuestra Señora del Pilar Educational Institution,” Magister Thesis, Fundación Universitaria Los Libertadores, 2017.

- C. Freinet, Los Metodos Naturales III: El aprendizaje de la escritura, Editorial Fontanella, 1972.

- M. Pantigoso, Educación por el arte. Hacia una pedagogía de la expresión, Instituto Nacional de Cultura, 1994.

- C. H. Ramirez, “Academic Audit on the Impact of the Administrative Process on the Achievement of Educational Quality Standards of the SISE Institute of San Juan De Lurigancho – 2017,” Magister Thesis, Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal, 2017.

- A. Teberosky and L. Tolchinsky, “Beyond initial reading and writing,” J. Study Educ. Dev., 15(58), 5–14, 1992.

- J. R. Reyes, Y. N. Villegas, “Metacognition in university education. A case study,” Rev. Electrónica Psicol. Iztacala, 22(2), 2277-2290, 2019.

- G. H. Chinga, J. A. Meza, “Production of narrative texts in students of the 5th cycle of primary education in a school in Pachacútec,” Bachellor Thesis, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, 2012.