Distance Teaching-Learning Experience in Early Childhood Education Teachers During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Distance Teaching-Learning Experience in Early Childhood Education Teachers During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Volume 6, Issue 1, Page No 269-274, 2021

Author’s Name: Wilfredo Carcausto1,a), Juan Morales2, María Patricia Cucho-Leyva1, Noel Alcas-Zapata1, Mirella Patricia Villena-Guerrero1

View Affiliations

1Cesar Vallejo University, 15314, Peru

2University of Sciences and Humanities, E-Health Research Center, 15314, Peru

a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: wcarcaustocalla@ucvvirtual.edu.pe

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 6(1), 269-274 (2021); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj060131

DOI: 10.25046/aj060131

Keywords: Remote Teaching, Virtual Teaching, Early Childhood Education

Export Citations

The purpose of the study was to describe the experiences of teachers in the distance teaching-learning process in early childhood education during the covid-19 pandemic. The methodology used was qualitative descriptive. Interviews were conducted with thirteen teachers from four state educational institutions at the infant level in Lima city through the virtual platform. As a result of the data analysis, five subcategories emerged: Emotions in remote teaching at the beginning of the school year during the pandemic, communication between teachers and families for student learning, management and adaptation of remote teaching-learning, be a teacher of childhood education during the pandemic, and accompaniment in the teaching-learning process. In conclusion, the distance teaching-learning experience of teachers at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic is characterized by the presence of certain negative emotions and attitudes towards their educational work; however, self-training on digital and computer resources and empathy with families have improved the generation of learning situations in children.

Received: 28 October 2020, Accepted: 21 December 2020, Published Online: 15 January 2021

1.Introduction

The global health situation due to the coronavirus (Covid-19) had social, cultural, economic, and educational effects [1]. Almost 94% of students worldwide, in 190 countries, presented interruption of their academic activities due to policies implemented by governments to mitigate the effects of the pandemic [2] There is a decline in the economy in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean because of the serious health crisis by the coronavirus [3]. In this context, remote education has been implemented with unprecedented speed, due to the fact that the countries did not have a consolidated national distance education strategy, even less for a scenario in emergency situations [4], [5].

Currently, all teachers at different educational levels are working from home with the resources at their disposal and their conceptions of teaching and learning [6]. The Government of Peru suspended educational activities in public and private entities to reduce the effects of the pandemic. However, since April 6, 2020, the school year began through the implementation of the strategy “I learn at home” to preserve the continuity of educational services [7]. More than six million users through a thousand radio stations nationwide follow weekly the transmission of this strategy [8].

In this context, Peruvian teachers took on a new challenge, and this implied leaving the classrooms and beginning to teach through virtual environments within the framework of the strategy promoted by the government. However, this teaching modality required the accompaniment of teachers to acquire the necessary digital skills that allow them to handle digital tools for educational purposes. Before the pandemic, the government had not paid due attention, although there were already several published documents on the development and application of these competencies in early childhood education, primary and secondary teachers [9].

During the pandemic, teachers had to learn to use digital resources quickly, to generate learning situations with students and interact with their peers. Currently, teachers can be trained and reinforce their skills through the “Perueduca” digital learning system.

The transition from the face-to-face modality to remote early childhood education is a complex process due to the work carried out with children from three to five years old. The little development of digital skills of the teachers, the insufficient use of the internet by children through mobile devices or computers, forced parents to accompany their children in the teaching-learning process provided by teachers. The remote teaching and learning process in children requires the participation of four actors: teachers, students, parents and the media such as television [10], and digital devices[11], [12].

Distance education leads teachers to use different teaching strategies and resources to facilitate children’s learning [13]. In the case of early childhood education, teachers must capture children’s attention and enable the construction of their own learning, which requires the guidance and accompaniment of parents. On the part of teachers, it requires a great commitment to the development of digital skills, the use of resources and materials appropriate to the age and needs of children, because they have less developed levels of physical and verbal skills, and are less capable to work alone [14].

In face-to-face teaching, the same physical space is shared and carried out at the same time; while in remote teaching, the instruction is at a distance [15], and pedagogical activities can be carried out synchronously and asynchronously [16]. Likewise, in face-to-face learning, learning sessions were planned by applying pedagogical processes, while in distance teaching learning experiences were planned. Both must be evaluated in a formative way, so that teachers can observe how the process of acquisition of learning is happening, they need the evidence of the children and based on this evidence, give feedback individually, to obtain information on the development of the competitions.

So far there are no known studies of remote teaching and learning experiences with preschool children, although some research has been found related to the virtual teaching practices of students from a university in the United States [17], and a Spanish public university [18]. Furthermore, digital technologies have the potential both to facilitate communicative and creative tasks and to expand children’s repertoires [19].

Therefore, the objective of this work is to describe the experiences of teachers in the remote teaching and learning process at the Early Childhood Education level during the coronavirus pandemic.

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

In this study, the qualitative description was the methodology adopted [20], which allowed to explore in-depth the experiences in the teaching of early childhood teachers in the context of a health emergency. This method was used in order not to stray from the literal description of the experiences reported from the point of view of the participants [21].

This method allows reporting the results based on the subcategories that emerged from the interviews that were interpreted and compared with previous studies.

The results consist of a synthesis based on the subcategories that emerged from the interviews, previously interpreted with the support of the existing literature, and compared with other studies.

2.2. Participants

The study population was made up of 26 early childhood education teachers belonging to the following State Early Childhood Education Centers located in three districts of Lima, Peru: “Francisco Bolognesi” and “José Antonio Encinas” (located in the Santa Anita district), “Los Ángeles de Jesús” (in Rímac district), and “Los Libertadores” (located in Los Olivos district). These teachers have conducted distance classes and have applied the “I learn at home” strategy proposed by the Ministry of Education (MINEDU).

All the participants were recruited when they were undertaking postgraduate studies at a private university in the North of Lima. The sample was selected considering the following process: In the first phase, an invitation was sent by email to 26 teachers, of which 18 voluntarily agreed to participate and signed the informed consent. In the second phase, according to the saturation criteria, there were 13 teachers left, who became the final sample of the study.

The families of the children with whom the teachers work are of low socioeconomic status, most of them work independently and have a complete secondary level.

2.3. Data collection

A semi-structured interview prepared by the researchers was used for data collection. Before its application, it was piloted in 3 teachers who had similar characteristics of the participants in the study, in order to know the relevance of the open questions, as well as to know their experiences regarding the central theme of the study.

After validation of the question guide, the participating teachers provided information on their pedagogical experiences according to the following guiding questions: Tell me, at the beginning of the school year, when the coronavirus pandemic also began, how was your remote teaching-learning experience with the children? What helped you cope with these experiences without being in face-to-face classes? Today, what does it mean to you to be a Remote teacher of Early Childhood Education?

The interviews were recorded and transcribed with the consent of the participating teachers. The interview was conducted in August 2020 through the Zoom® platform, with a duration between 20 and 25 minutes per interview.

2.4. Data analysis

The interviews were analyzed through the thematic analysis method [22]. This method allows us to identify, analyze, organize, and report topics within the data set described in detail. Thematic analysis has various uses, which allows informing experiences, meanings, and the reality of the participants. In the present study, the transcripts, reading, and rereading of the collected information was carried out. Subsequently, the units of meaning that served to summarize and express empirical categories were identified. Finally, results were interpreted, without departing from the literal description of the phenomenon under study [20].

Two aspects related to the validity of the study should be noted. First, to comply with the rigor of the credibility of the data, once the interviews were transcribed they were delivered to the participants so that they corroborate and accredit the information provided by them. Second, to illustrate the empirical or emerging subcategories, relevant quotes from the interviews were selected. Also, an expert evaluated the information in order to give credibility to the data analysis carried out by the researchers.

3. Results

The expressions of the interviewees made it possible to understand the experiences of the initial level teachers in remote education implemented by the Peruvian state during the period of confinement by COVID-19.

Table 1: Characteristics of the interviewees

| Characteristics | n | % |

| Total | 13 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| < 34 | 5 | 38.5 |

| 34 a 38 | 4 | 30.7 |

| 38 a 44 | 2 | 15.4 |

| >45 | 2 | 15.4 |

| Civil status | ||

| Married | 5 | 38.5 |

| Single | 5 | 38.5 |

| Widow | 1 | 7.6 |

| Divorcee | 2 | 15.4 |

| Employment status | ||

| Appointed | 8 | 61.5 |

| Hired | 5 | 38.5 |

| Academic degree | ||

| Doctorate | 1 | 7.6 |

| Master | 8 | 61.5 |

| Bachelor | 4 | 30.7 |

| Educational institution | ||

| Public | 13 | 100 |

From the thirteen participating teachers, eight have a master’s degree, one of them with a doctoral degree, and four have a bachelor’s degree and are currently pursuing a master’s degree.

According to the employment status, eight had appointed condition and five hired. The largest proportion of teachers were under 34 years of age as shown in Table 1.

According the interviews carried out with the initial education teachers and the data analysis, five sub-categories finally emerged from the reports as initial education teachers during the health crisis: Emotions in remote teaching at the beginning of the school year during the pandemic, communication between teachers and families for student learning, management and adaptation of remote teaching-learning, be a teacher of childhood education during the pandemic, and accompaniment in the teaching-learning process (Table 2).

Table 2: Categorization of qualitative information

| Study Category | Subcategories |

| Distance teaching and learning | Emotions in remote teaching at the beginning of the school year. |

| Communication between teachers and families for student learning. | |

| Management and adaptation of remote teaching learning. | |

| Be an early childhood education teacher during the pandemic. | |

| Accompaniment in the teaching-learning process. |

3.1. Study Category: Distance Teaching and Learning

It refers to a modality of distance instruction that is provided to students as a result of the state of health emergency in which didactic activities are carried out both asynchronously and synchronously.

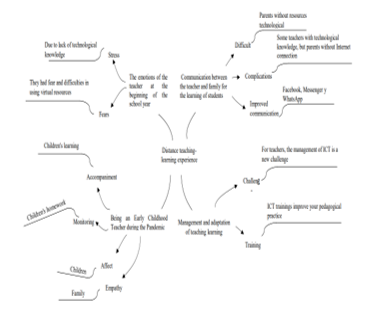

Figure 1: Units of meaning of the participants

Figure 1: Units of meaning of the participants

In this context, from the descriptive analysis of the qualitative information available in the interviews, subcategories related to the study categories emerged: In the emotions subcategory of the teachers, emotional states such as stress and fear were identified. The subcategory communication between teachers and families for student learning shows expressions: Difficult, complicated, communication improvement. From the management and adaptation of teaching-learning expressions such as sacrifice, training, challenge, and knowledge were found. The subcategory to be a beginning level teacher during the pandemic shows expressions such as accompaniment, monitoring, emotional support, flexibility, and empathy (Figure 1).

3.2. Emotions in remote teaching at the beginning of the school year during the pandemic

At the beginning of the school year during the pandemic, the emotional situations and negative attitudes of the teachers were linked to the poor use of digital and computer tools, but were subsequently overcome. A part of the teachers have expressed that these tools should be integrated as a complement to face-to-face teaching.

“It was very difficult and stressful at the beginning, as I had little computer knowledge. Thank God, I am already learning and driving better and better. Actually, I thought it was difficult”. E7

“At the beginning I saw it somewhat difficult to work remotely with the children, but as the days went by I realized that technology was a valuable resource to learn and teach at the same time”. E12

“At the beginning, I presented many fears and difficulties in handling the virtual, but to date I have been teaching and interacting better with my students. (…) I think that this experience with technology should not be put aside when we return to class”. E4

3.3. Communication between teachers and families for student learning

The beginning of the school year in the context of the coronavirus pandemic was complicated for teachers because families lacked technological resources (computer and laptop), management of virtual platforms and mobile devices with internet connection. These elements allow for proper storage and communication between students and teachers. Currently, they communicate with families through social networks such as Facebook, Messenger and WhatsApp.

“(…) At the beginning it was difficult, since many of the parents did not have experience with the platforms that MINEDU offers, they did not have computers either, so I had to hold several meetings through social networks such as WhatsApp and Facebook”. E9

At the beginning, it was quite complicated and stressful, I had knowledge of ICT (…) but contacting parents was very difficult, since most did not have a computer and a laptop. Now we have organized ourselves better and we communicate by messenger and WhatsApp”. E13

3.4. Management and adaptation of remote teaching-learning

The teachers mentioned that the management of any remote teaching resources and their updating contributed to their adaptation; the generation and development of learning situations in their students.

“I knew something about the use of ICT, I think that made it easier for me to adapt to the new way of teaching.” E1

“I see that I am having a hard time adjusting to teaching remotely. Two months ago I took training for virtual teaching, which is helping me to give the best of myself to my students”. E3

“Little by little I continue to adapt to this new challenge, thanks to the courses promoted by PerúEduca and the tutorials on YouTube.” E8

“Little by little I am getting used to the management of these resources, I am seeing that there are many resources that can be used, I still lack quick management of these.” E10

- Be an early childhood education teacher during the pandemic

According to the participants, being an early childhood education teacher during the pandemic is associated with the accompaniment, monitoring, and emotional support of students through their families during their learning process.

“Much support, not only in the learning of the children but also in the family in general, I call them, I write them on WhatsApp phrases of encouragement, motivational messages. E1

“(…) Be a companion and dynamic with the children and be in communication with the family to remotely monitor the progress of the children’s tasks at home.” E4

“Be flexible, and monitor through parents, the tasks that are sent to children by WhatsApp.” E11

From the expressions interviewed, the teacher must be empathetic and maintain a good relationship with the students’ families, because they act as a link to interact and generate learning situations in the students.

“It is a role of accompaniment, follow-up, and affection, because they need at all times (…) and very empathetic with mothers because they are our allies in their children’s learning”. E3

“It is having empathy, especially with parents, because most of them work. And very affectionate and charismatic with children so that they can learn and develop their skills ”. E13

3.6. Accompaniment in the teaching-learning process

According to the participants, the accompaniment is given through feedback after receiving the evidence from the students. In this process, they have managed to identify the term of feedback and improve their pedagogical practices.

From what was expressed, the teachers interact using social networks, obtaining greater impact for the teaching-learning process, as well as understanding how they should carry out feedback to obtain information about learning.

“[…] I accompany my students on WhatsApp, according to the information provided by the mothers about the difficulties or doubts that their children may have in doing their homework”. E 4

“In the past, we had difficulty giving feedback in the classroom, now we do it individually, through social networks to evaluate children”. E13

4. Discussion

This study describes the experiences of early childhood education teachers in the remote teaching and learning process within the framework of the implementation of the strategy “I learn at home” to guarantee the continuity of educational services [7]. From the analysis and synthesis of From the interview data, four subcategories were found, in which emotional experiences, communication, management, adaptability, and the meaning attributed by teachers to their professional work are expressed.

Regarding the experiences and emotional expressions experienced by the teacher as a human being, they are currently more intense [23], due to the new health and social demands in which he had to live and fulfill his role as a professional for new generations.

Emotions, such as moods and feelings, are manifested as responses, signals, or reactions about what is going well for us or what is going wrong, about what we like or dislike[24]. In this sense, the teacher as a human being, manifests these emotions in their inner world, even more so in situations of the pandemic by Covid-19 and being responsible for the training of children who need to continue learning.

The teachers who participated in this study, at the beginning of their work, showed fear and negative attitudes with remote work during the suspension of face-to-face classes due to Covid-19. This result allows us to infer that teaching in times of uncertainty and tension provokes in teachers the presence of certain negative emotions with greater or lesser intensity, amplitude, and continuity in pedagogical practice [25], [26].

On the other hand, despite having had a complicated beginning, the experience of using resources for remote teaching-learning should be integrated into face-to-face classes. From these expressions, it can be interpreted that at first, it was not easy to tune into the remote teaching modality, either due to circumstances generated by themselves and/or beyond their control. There was also a second moment, which could be called empowering resources for remote teaching, which implies not only seeing technology (television, radio, computers, portable and mobile devices) as a mere didactic resource but as a component that influences teaching and learning.

Our results are similar to other studies [27], [28]. Generating good communication channels for educational purposes between teachers and parents favors student learning, especially if they are minors.

In this process of communication and interaction, the teachers must explain the importance of the role of the family in “accompanying children in carrying out tasks and listening to their concerns, preparing spaces and times for tasks” [29], also communicating with the teachers in this distance teaching-learning journey.

The teachers at the beginning of the year had difficulties communicating with the families since most lacked technological resources and had limited use of them. This situation is understandable since the families are of low socioeconomic status and with a secondary education level. Despite this, families with the intention that their children do not miss the school year have continued to study and the teachers have assumed their role as an educational communicator. With the purpose of improving communication, Messenger® and WhatsApp® were used to coordinate the activities organized by the institution, consult or inform the doubts and difficulties of the children in carrying out the tasks at home. From the aforementioned, we can infer for teachers and families that being in a time of pandemic and with certain technological deficiencies may be an opportunity to strengthen communication and interaction through mobile devices that are available for the good of children’s development.

Man is a social being because he not only creates and transmits information, but also shares, thanks to this man can adapt to new situations. It is established that human beings are adaptive, that is, with the ability to adapt and create changes in the environment [30]. Along these lines, the participants in the study reported that they have fully adapted to remote teaching-learning, and they also recognize that they are updating and integrating their educational practice for better interaction and student learning. This means that adaptation to a scenario of uncertainty due to the health phenomenon and the rapid transit of the teacher to remote education in unfavorable conditions is not easy and probably never will be, although with affection for knowledge and being updated provides greater possibilities to overcome new situations and support students’ learning.

Just as every professional has a role in the execution of their activities, the basic education teacher has the responsibility of fulfilling the three roles established by the Ministry of Education of Peru [31]. These roles are related to identifying the means that the family members should use to access the materials, know the material, and the “I Learn at Home” schedule, and communicate with the family to monitor the progress and difficulties that the students may have. Along these lines, the initial education teacher, in addition to being a monitor and companion, is effective support in the students’ learning experience [13]. The findings of the present study agree with the aforementioned, as some characteristics are mentioned such as emotional support, accompaniment, and monitoring.

On the other hand, according to the interviews, it is important to take into account that children need affection, encouragement, and support that gives them security and autonomy in the development of their skills and abilities. These verbal data are similar to those found in [32], given that most of the teachers participating in this study value emotions in the classroom.

Likewise, the teachers consider maintaining an affective connection with the families and students so that mutual understanding is generated, in this way they would improve the learning of the students, because the accompaniment of the parents in their homes is added to this process, generating a shared commitment that would allow obtaining a quality education.

Regarding the teaching-learning resources, the teachers realized that it is possible to use technology at the initial level and it is not necessary to implement a technological classroom, which for the Ministry of Education is difficult due to economic limitations, in this sense considers it optimal to use social networks as resources in the teaching-learning process.

Among the limitations of the present study is the failure to use instruments that allow observing and understanding the teaching action from the platform in real-time. Likewise, not having considered preschoolers as a unit of study, which would have allowed them to know their learning experiences through their parents. For this reason, it is suggested to carry out research that includes other key actors with ethno-phenomenological approaches to go to the very essence of the phenomenon studied.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

In the remote teaching-learning process, at the beginning of the school year during the COVID-19 pandemic, early childhood education teachers showed certain negative emotions and attitudes due to lack of management of digital and informational resources.

For teachers, it was difficult to generate learning situations in children during the pandemic, since the majority of parents lacked technological resources or how to use them.

The self-training of teachers on digital and computer resources during the pandemic and empathy with families and affection for children have allowed them to fulfill their professional role. Accompaniment through feedback from social networks contributed to strengthening children’s learning.

We recommend that the heads of educational institutions strengthen the capacities of their teachers to apply formative assessment throughout the teaching-learning process of students. Provide training to parents to strengthen alliances through collaborative work to generate learning situations in students from home. Coordinate with managers and local authorities to guarantee connectivity in the places where the training action takes place.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

To all the Early Childhood Education teachers participating in the present study.

- Organización de Naciones Unidas para la Educación, “Enseñar en tiempos del Covid-19”. Una guía teórico-práctica para docentes, Montevideo, 2020.

- Organización de Naciones Unidas, “Policy Brief:Education during Covid-19 and beyond,” 2–26, 2020.

- B. Mundial, “El Banco Mundial pronostica una fuerte caída de la economía en América Latina por el coronavirus,” 2020.

- H. Álvarez, “Educación en tiempos de coronavirus,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53(9), 1689–1699, 2020, doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- H. Habib, C. González, C.A. Collazos, M. Yousef, “Estudio exploratorio en iberoamérica sobre procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje y propuesta de evaluación en tiempos de pandemia,” Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 21(0), 9, 2020, doi:10.14201/eks.23537.

- F. Trujillo Sáez, M. Fernández Navas, A. Segura Robles, M. Jiménez López, Escenarios de evaluación en el contexto de la pandemia por la Covid – 19: la opinión del profesorado, 2020.

- Ministerio de Educación, “Resolución Ministerial 160-2020-MINEDU,” Diario El Peruano, 15, 2, 2020.

- Instituto Peruano de Economía, “Informe IPE,” Segundo Informe: Análisis Del Impacto Económico Del Covid-19 En El Perú, 1–25, 2020.

- CanopyLAB, “¿Cuál es la situación de las competencias digitales docentes en América Latina?,” 2020,.

- E. Sánchez, D. Benito, “Educar, cuestión de cuatro: Padres, maestros, niños y TV,” Comunicar, 16(31), 254–249, 2008, doi:10.3916/c31-2008-03-001.

- L. Plowman, “Researching young children’s everyday uses of technology in the family home,” Interacting with Computers, 27(1), 36–46, 2015, doi:10.1093/iwc/iwu031.

- R. Brito, P. Dias, “Digital Technologies, Learning and Education: Practices and Perceptions of Young Children (Under 8) and Their Parents,” Ensayos-Revista De La Facultad De Educacion De Albacete, 31(2), 23–40, 2016.

- C. Castaño, “El rol del profesor en la transición de la enseñanza presencial al aprendizaje ‘on line,’” Comunicar: Revista Científica Iberoamericana de Comunicación y Educación, 21, 49–55, 2003, doi:10.3916/25547.

- E. Ramirez, J. Martín-Dominguez, M. Madail, “Análisis comparativo de las prácticas docentes con recursos TIC. Estudio de casos con profesores de Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria,” Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Educativa (RELATEC), 15(3), 141–154, 2016, doi:10.17398/1695.

- A.O. Mohmmed, B.A. Khidhir, A. Nazeer, V.J. Vijayan, “Emergency remote teaching during Coronavirus pandemic: the current trend and future directive at Middle East College Oman,” Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, 5(3), 1–11, 2020, doi:10.1007/s41062-020-00326-7.

- M.L. Picón, “¿ Es posible la enseñanza virtual?,” 11–34, 2020.

- J. Kim, “Learning and Teaching Online During Covid-19: Experiences of Student Teachers in an Early Childhood Education Practicum,” International Journal of Early Childhood, 52(2), 145–158, 2020, doi:10.1007/s13158-020-00272-6.

- G. González-Calvo, D. Bores-García, R.A. Barba-Martín, V. Gallego-Lema, “Learning to be a teacher without being in the classroom: Covid-19 as a threat to the professional development of future teachers,” International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 152–177, 2020, doi:10.17583/rimcis.2020.5783.

- J. McPake, L. Plowman, C. Stephen, “Pre-school children creating and communicating with digital technologies in the home,” British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(3), 421–431, 2013, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01323.x.

- M. Sandelowski, “Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description?,” Research in Nursing and Health, 23(4), 334–340, 2000, doi:10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g.

- C. Bradway, “HHS Public Access,” Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review, 40(1), 23–42, 2018, doi:10.1002/nur.21768.Characteristics.

- V. Braun, V. Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(May), 58, 2006.

- C. Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Estrada, V., Freeman, A. & Hall, Horizon Report > 2016 Higher Education Edition, 2016.

- A. Abramowski, Maneras de querer.Los afectos docentes de las relaciones pedagógicas., Buenos Aires, 2010.

- U.A. Marchesi, F.T. Díaz, Emociones y valores del profesorado, Madrid, 2008.

- R. Silvana, G. Lugli, “Representaciones de las emociones del trabajo docente en perspectiva histórica,” Educación e Investigación, 46, 1–12, 2020, doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046217120.

- M. Borjas, C. Ricardo, M. Herrera, E. Vergara, A.E. De Castro, “Digital educative resources for childhood education (REDEI in Spanish),” Zona Próxima, 44(20), 1–21, 2014, doi:10.14482/zp.20.5888.

- S. Villarreal-Villa, J. García-Guliany, H. Hernández-Palma, E. Steffens-Sanabria, “Teacher competences and transformations in education in the digital age,” Formacion Universitaria, 12(6), 3–14, 2019, doi:10.4067/S0718-50062019000600003.

- C. Castro, Acompañar la tarea del equipo docente, las familias y las y los estudiantes en casa, Buenos Aires, 2020.

- L.& otros Díaz, Análisis de los conceptos del modelo de adaptación de Callista Roy, Aquichan, 2, 19–23, 2009, doi:10.5294/18.

- Ministerio de Educación, ¿Cuál es el rol de los y las Docentes?, Lima- Perú, 2020.

- E. Trujillo González, E.M. Ceballos Vacas, M.D.C. Trujillo González, C. Moral Lorenzo, “El papel de las emociones en el aula: Un estudio con profesorado canario de Educación Infantil,” Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación Del Profesorado, 24(1), 2020, doi:10.30827/profesorado.v24i1.8675.