Case Report

Tumours of the Uterine Corpus: A Histopathological and Prognostic Evaluation Preliminary of 429 Patients

Jorge F Cameselle-Teijeiro1,2,3*, Javier Valdés-Pons1,3, Lucía Cameselle-Cortizo3, Isaura Fernández-Pérez1, MaríaJosé Lamas-González1, Sabela Iglesias-Faustino1, Elena Figueiredo Alonso4, María-Emilia Cortizo-Torres1,3, María-Concepción Agras-Suárez4, Araceli Iglesias-Salgado3, Marta Salgado-Costas3, Susana Friande-Pereira1 and Fernando C Schmitt2

1Universitary Hospital of Vigo, Spain

2IPATIMUP- Institute of Molecular Pathology and Immunology of the University of Porto, Portugal

3Clinical Oncology Research Center ADICAM, Cangas, Spain

4Povisa Medical Center, Vigo, Spain

*Address for Correspondence: Jorge F Cameselle Teijeiro, MD-PhD, Clinical Oncology Research Center ADICAM Travesía de Vigo nº 2, 2º C VIGO 36206 VIGO, Spain, E-mail: videoprimaria@mundo-r.com

Dates: Submitted: 30 December 2016; Approved: 27 January 2017; Published: 30 January 2017

How to cite this article: Cameselle-Teijeiro JF, Valdés-Pons J, Cameselle-Cortizo L, Fernández-Pérez I, Lamas-González MJ, et al. Tumours of the Uterine Corpus: A Histopathological and Prognostic Evaluation Preliminary of 429 Patients. J Clin Med Exp Images. 2017; 1: 011-019.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcmei.1001004

Copyright License: © 2017 Cameselle-Teijeiro JF, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Tumours of the uterine corpus; Endometrial cancer; Uterine serous carcinoma; Epidemiology

ABSTRACT

A histopathological review preliminary of 429 patients diagnosed with tumours of the uterine corpus (TUC) cancer between 1984- 2010 in the Vigo University Hospital Complex (Spain) were evaluated prospectively for over 5 years. Of these 403 (93.9%) were epithelial tumours: 355 (82.7%) were adenocarcinomas of the endometrioid type, 5 (1.1%) mucinous adenocarcinoma, 10 (2.3%) serous adenocarcinoma, 17 (3.9%) clear cell carcinomas, 11 (2.5%) mixed adenocarcinoma, 4 (0.9%) undifferentiated carcinomas and 1 (0.2%) squamous cell carcinomas. A total 20 (4, 6%) were mesenchymal tumours: 4 (0.9%) endometrial stromal sarcoma, 7 (1.6%) Leiomyosarcoma, 9 (2%) Mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumour. A total 1 (0.2%) were mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours: (0.2%) Adenosarcoma 1. And 5 (1.1%) were Metastases from extragenital primary tumour (3 carcinomas of the breast, 1 stomach and 1 colon). The mean age at diagnosis from total series were 65, 4 years (range 28-101 years). Age was clearly related to histologic type: Endometrial stromal sarcoma 46.0 years, Leiomyosarcomas 57.1 years, Adenocarcinomas of the endometrioid type 65.4 years, Clear cell carcinomas 70.1 years and mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumours 71.2 years. Five-year disease-free survival rates for the entire group were: Endometrial stromal sarcoma 50%, Leiomyosarcomas 28.6%, Adenocarcinomas of the endometrioid type 83.7%, Clear cell carcinomas 64.7% and mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumours 44.4%. The 5-year disease-free survival rates of patients with Adenocarcinomas of the endometrioid type tumors were 91.4% for grade 1 tumors, 77.5% for grade 2, and 72.7% for grade 3.

In conclusion, we describe 5-year histological and disease-free survival data from a series of 429 patients with TUC, observing similar percentages to those described in the medical literature. The only difference we find with other published series is a slightly lower percentage of serous carcinomas (ESC) that the Western countries but similar to the 3% of all ESC in Japan. Our investigation is focus at the moment on construct genealogical trees for the possible identification of hereditary syndromes and to carry out germline mutation analysis.

INTRODUCTION

The tumours uterine corpus (TUC) represents the second most common site for malignancy of the female genital system. These neoplasms are divided into epithelial, mesenchymal, mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours and throphoblastic tumours [1].

Endometrial cancer is the third most common cause of death among gynecological cancers, following ovarian and cervical cancer, with increasing incidence rates in several countries, and its incidence is increasing. It is the most curable of the 10 most common cancers in women and the most frequent and curable of the gynecologic cancers. Ninety-seven percent of all TUC arise from the glands of the endometrium and are known as endometrial carcinomas. The most frequently occurring histological subtype is endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The remaining 3 percent of uterine cancers are sarcomas [2,3].

Thirty years ago, Bokhman hypothesized there were two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinomas [4]. The author presented a hypothesis that the complex of endocrine and metabolic disturbances arising long before the development of endometrial carcinoma determines the biological peculiarities of the tumor, its clinical course, and the prognosis of the disease. Type 1 is more common (70-80%), consisting of endometrioid, low grade, diploid, hormone-receptor positive tumors that are moderately- or well-differentiated and more common in obese women. Patients presenting with Type 1 tumors tend to have localized disease confined to the uterus and a favourable prognosis. In contrast, Type 2 tumors (20-30%) are more common in non-obese women, of nonendometrioid histology, high-grade, aneuploid, poorly differentiated, hormone receptor negative and associated with higher risk of metastasis and poor prognosis. While this historical system of taxonomy has been useful, substantial heterogeneity within and overlap between Type I and II cancers is now recognized. Type I and Type II designation has never been part of the formal staging nor risk stratification, and thus has no clinical utility beyond providing a conceptual framework for understanding endometrial cancer pathogenesis. Murali et al. [5]. Points out that there is substantial heterogeneity in the biological, pathological and molecular characteristics within the tumor types of both classification systems and provides an overview of the traditional and more recent genomic classifications of endometrial cancer.

Standard treatment consists of primary hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, often using minimally invasive approaches (laparoscopic or robotic). Lymph node surgical strategy is contingent on histological factors (subtype, tumour grade, involvement of lymphovascular space), disease stage (including myometrial invasion), patients’ characteristics (age and comorbidities), and national and international guidelines. Adjuvant treatment is tailored according to histology and stage. Various classifications are used to assess the risks of recurrence and to determine optimum postoperative management. 5 year overall survival ranges from 74% to 91% in patients without metastatic disease. Trials are ongoing in patients at high risk of recurrence (including chemotherapy, chemoradiation therapy, and molecular targeted therapies) to assess the modalities that best balance optimisation of survival with the lowest adverse effects on quality of life [6-8].

Clarke et al. [9]. Reviews the various grading systems that have been proposed for use with endometrioid endometrial carcinoma, and discusses the recent progress in cell type assignment, including the use of immunohistochemistry as a diagnostic adjunct.

For Talhouk et al. [10]. The categorization and risk stratification of endometrial carcinomas is inadequate; histomorphologic assessment shows considerable interobserver variability, and risk of metastases and recurrence can only be derived after surgical staging. They have developed a Proactive Molecular Risk classification tool for endometrial cancers (ProMisE) that identifies four distinct prognostic subgroups.

Hereditary endometrial carcinoma is associated with germline mutations in Lynch syndrome genes. The role of other cancer predisposition genes in endometrial carcinoma is unclear. Identification of hereditary forms of neoplasias among cancer patients is crucial for better management and prevention of other syndrome-associated malignancies for the patients and their families.

Our objective is to perform a preliminary histopathological and prognostic study of a consecutive series of 429 TUC. Subsequently, we will study the family aggregation of cancer in each of the probands with the objective of identifying hereditary syndromes associated with some of these tumors in a cohort of non-selected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data from 429 women with TUC treated between November 1984 to September 2010 at two institutions university from Vigo (Spain): Xeral Hospital and Meixoeiro Hospital were collected diagnosed from endometrial biopsies and hysterectomy specimens received in the Department of Pathology were included in the study. All specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin embedded for histological examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining. The clinicopathological analysis of the cases of TUC was done with emphasis on morphology and clinical follow-up.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed using χ2 tests. Variables significant in the univariate analysis were subsequently entered into a multivariate analysis (MVA) using the Cox proportional hazards ratio model. Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of progression, date of death, or date of last follow-up if the patient was alive. Time to any event was measured from the date of diagnosis. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated from the survival data. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software for Windows version 12.0 (SPSS). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

RESULTS

Among the 429 TUC analyzed in the current study, the most frequent ones (93.9%) were found in epithelial tumours. Only 4.6% were mesenchymal tumours. And 5 cases (1.1%) were metastases from extragenital primary tumour: 3 carcinomas of the breast, 1 stomach and 1 colon (Table 1). In the overall study group, the median age of diagnosis was 65.4 years (range, 28 to 101 years). Endometrial stromal sarcomas affect younger women with a mean age of 46 years with ranges of 36-52 years, clearly lower than the age from global serie (p <0.01)

| Table 1: Number of patients and mean age in years, according to histological type. | |||||

| Nº of patients | Type and histological grade | Nº | Median age (DS) years | ||

| Epithelial tumours | 403 (93.9%) | carcinoma the endometrioid type | Grade 1: 51 % | 355 | 65.4 (11.4) |

| Grade 2: 32 % | |||||

| Grade 3: 17 % | |||||

| mucinous adenocarcinoma | Grade 1: 40 % | 5 | 61.6 (8.8) | ||

| Grade 2: 60 % | |||||

| serous adenocarcinoma | Grade 3: 100 % | 10 | 67.3 (10.1) | ||

| clear cell carcinoma | Grade 3: 100 % | 17 | 70.1 (11.3) | ||

| mixed adenocarcinoma | Grade 1: 20 % | 11 | 66.8 (15.1) | ||

| Grade 2: 40 % | |||||

| Grade 3: 40 % | |||||

| undifferentiated carcinomas | Grade 3: 100 % | 4 | 70.2 (10.3) | ||

| squamous cell carcinomas | 1 | 54 | |||

| Mesenchymal tumours | 20 (4,6%) | endometrial stromal sarcoma | 4 | 46 (6.9) | |

| leiomyosarcoma | 7 | 57.1 (13.1) | |||

| Mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumour | 9 | 71.2 (7.3) | |||

| Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours | 1 (0.2%) | Adenosarcoma | 1 | 67 | |

| Metastases from extragenital primary tumour | 5 (1.1%) | Metastases from extragenital primary tumours previous (3 carcinomas of the breast, 1 stomach and 1 colon) |

Breast | 80 | |

| Breast | 46 | ||||

| Breast | 55 | ||||

| Stomach | 53 | ||||

| Colon | 82 | ||||

| TOTAL | 429 | 65.4 years (DS 16.6) | |||

Of these 403 (93.9%) were epithelial tumours: 355 (82.7%) were adenocarcinomas of the endometrioid type, 5 (1.1%) mucinous adenocarcinoma, 10 (2.3%) serous adenocarcinoma, 17 (3.9%) clear cell carcinomas, 11 (2.5%) mixed adenocarcinoma, 4 (0.9%) undifferentiated carcinomas and 1 (0.2%) squamous cell carcinomas. A total 20 (4.6%) were mesenchymal tumours: 4 (0.9%) endometrial stromal sarcoma, 7 (1.6%) leiomyosarcoma, 9 (2%) mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumour. A total 1 (0.2%) were mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours: (0.2%) adenosarcoma 1. And 5 (1.1%) were metastases from extragenital primary tumours previous: 3 carcinomas of the breast, 1 stomach and 1 colon. The mean age at diagnosis from total series were 65.4 years (range 28-101 years). Age was clearly related to histologic type: endometrial stromal sarcoma 46.0 years, leiomyosarcomas 57.1 years, adenocarcinomas of the endometrioid type 65.4 years, clear cell carcinomas 70.1 years and mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumours 71.2 years.

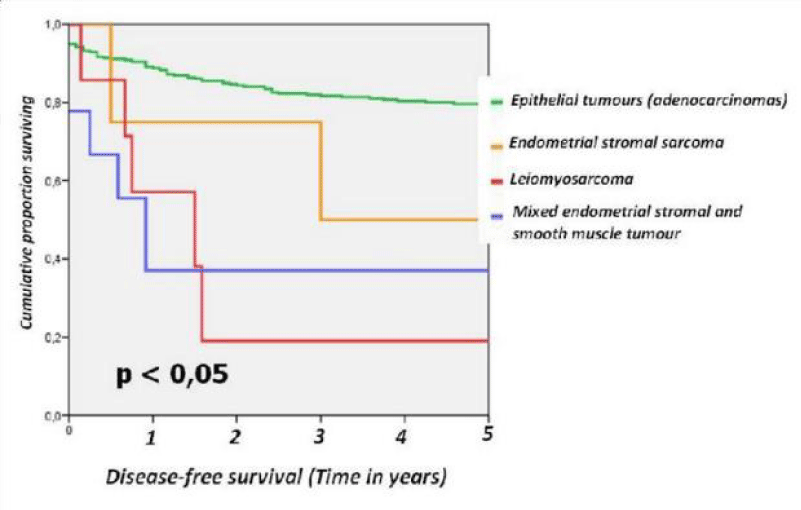

For the different subtypes of TUC the 5-year disease-free survival rates were as follows: epithelial tumours (adenocarcinoma) 80.8%, endometrial stromal sarcoma 50%, leiomyosarcoma 28.6% and mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumour 44.4 % (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Disease-free survival from series endometrial epithelial tumours divided epithelial tumours, endometrial stromal sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma and mixed endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumour.

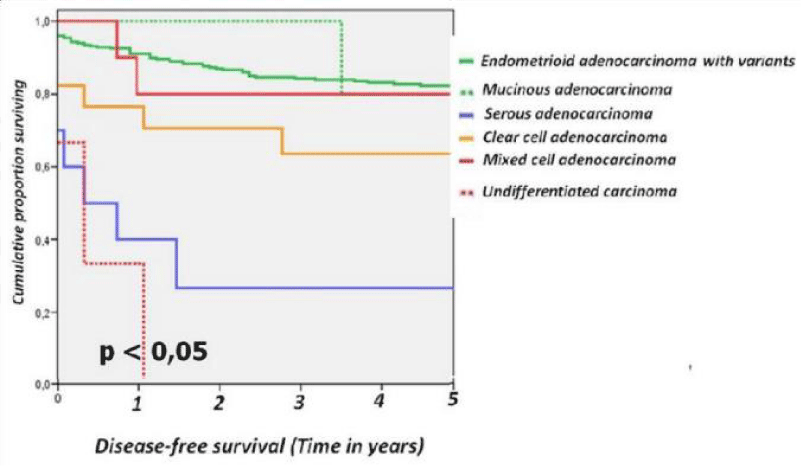

For the different subtypes of epithelial tumours of the uterine the 5-year disease-free survival rates were as follows: endometrioid adenocarcinoma with variants 83.4%, mucinous adenocarcinoma 80%, serous carcinoma 30 %, clear cell carcinoma 64.7 %, mixed cell carcinoma 81.8% and undifferentiated carcinoma 0% (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Disease-free survival from series epithelial tumours divided into endometrioid carcinoma and variants, mucinous adenocarcinoma, serous adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, mixed cell adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma.

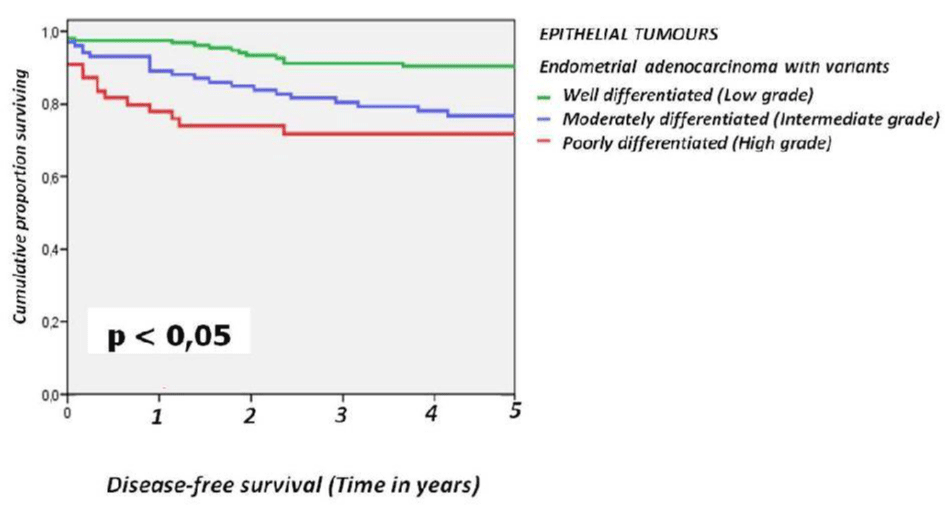

For the epithelial tumours the 5-year disease-free survival rates were 91.4% for grade 1 tumors, 77.5% for grade 2, and 72.7% for grade 3 (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

Tumors that occur in the uterine corpus include epithelial, mesenchymal, mixed epithelial and mesenchymal, miscellaneous, lymphoid and myeloid and secondary tumors, as well as trophoblastic disease [1]. In this study, we have described the histological distribution of 429 TUC and its relation to 5-year disease-free survival. The endometrial carcinoma is defined as a primary malignant epithelial tumour, usually with glandular differentiation, arising in the endometrium. It´s the most common malignant tumour of the female genital system in developed countries. In our series he represented the 93.9% (403 patients), which coincides with practically all published series [1,11]. Rose explains that the ninety-seven percent of all cancers of the uterus arise from the glands of the endometrium and are known as endometrial carcinomas [2]. Of the global serie of 403 epithelial tumours: 355 (82.7%) were adenocarcinomas of the endometrioid type. These carcinomas may exhibit a variety of differentiated epithelial types, when prominent in a carcinoma the neoplasm is termed a “special variant” carcinoma.

Type II endometrial carcinomas are non estrogen related, non endometrioid type. These generally occur in women a decade later than type I carcinoma, and in contrast to type I carcinoma they usually arise in the setting of endometrial atrophy. In the series of Mendivil et al. [12] the most common non-endometrioid histology is papillary serous (10%), followed by clear cell (2% to 4%), mucinous (0.6% to 5%), and squamous cell (0.1% to 0.5%). In the serie of Cirisano et al. [13] the frequency of tumors accounted were papillary serous 8%, clear cell adenocarcinoma 2%, and endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium for 90% of cases. Some non-endometrioid endometrial carcinomas behave more aggressively than the endometrioid cancers such that even women with clinical stage I disease often have extrauterine metastasis at the time of surgical evaluation. In Western countries, the endometrial serous carcinomas (ESC) only accounts for 10% of all uterine cancers, it is responsible for 40% of uterine cancer deaths [12-16], associated with a high proportion of advanced-stage disease at diagnosis and high recurrence rates (15). The percentage of ESC in our series were 2.3% slightly lower, similar to the 3% of all ESC in Japan [17].

Several research teams have defined immunohistochemical and/or mutation profiles to aid in distinguishing EC subtypes [18-22]. In one series, a set of seven immunohistochemical markers was able to improve the distinction between high-grade EC histotypes [23] and more recently, another team demonstrated a nine protein panel improved identification of both low and high-grade EC subtypes [24].

Classification of endometrial carcinomas by histomorphologic criteria has limited reproducibility and better tools are needed to distinguish these tumors and enable a subtype-specific approach to research and clinical care. Based on the Cancer Genome Atlas, two research teams have developed pragmatic molecular classifiers that identify four prognostically distinct molecular subgroups. These methods can be applied to diagnostic specimens (e.g., endometrial biopsy) with the potential to completely change the current risk stratification systems and enable earlier informed decision making [10].

We observed 5 patients with histological proven metastatic tumor from extragenital primary tumours previous: 3 carcinomas of the breast, 1 stomach and 1 colon. Kumar and Hart [25] describe a serie of 63 cases of metastatic cancers to the uterine corpus from extragenital neoplasms.

Hereditary endometrial carcinoma is associated with germline mutations in Lynch syndrome genes. Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition caused by a mutation in the mismatch repair (MMR) genes, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. The role of other cancer predisposition genes in endometrial carcinoma is unclear [26-31]. A small proportion of endometrial carcinomas might be the result of a genetic risk condition [32]. Lynch syndrome is the main syndrome involved in such cases [33,34], although the existence of a familial site-specific endometrial carcinoma genetic entity separate from Lynch syndrome has been sugested. Differences in the prevalence of genetic diseases are frequently observed between different populations, especially for syndromes where the penetrance is incomplete and other genetic and environmental factors might act as penetrance modifiers.

Current data on the prevalence of Lynch syndrome among unselected cases of endometrial carcinoma in North America range between 1.8% and 4.5% [35-37]. Significant differences in the prevalence of hereditary syndromes are frequently observed among different populations. Egoavil et al. [38] report a high prevalence of Lynch syndrome (4.6-6.6%) in a consecutive series of patients with endometrial carcinoma from the Spanish population, they consider that universal screening of all patients with ECs by IHC, MSI and MLH1 methylation analysis should be recommended.

In conclusion, we describe 5-year histological and disease-free survival data from a series of 429 patients with uterine body tumors, observing similar percentages to those described in the medical literature. The only difference we find with other published series is a slightly lower percentage of serous carcinomas. Our investigation is focus at the moment on construct genealogical trees for the possible identification of hereditary syndromes and to carry out germline mutation analysis.

REFERENCES

- Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS and Young RH: WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. WHO Classification of tumours. 6: (4TH). (Lyon). IARC Press. 122-167. 2014.

- Rose PG. Endometrial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 640-649. Ref.: https://goo.gl/fIWSnz

- Ueda SM, Kapp DS, Cheung MK, Shin JY, Osann K, et al. Trends in demographic and clinical characteristics in women diagnosed with corpus cancer and their potential impact on the increasing number of deaths. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198: 1-6. Ref.: https://goo.gl/VBuv4W

- Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983; 15:10-17. Ref.: https://goo.gl/2Jsq5S

- Murali R, Soslow RA, Weigelt B. Classification of endometrial carcinoma: more than two types. The Lancet 2014; 7: 268-278. Ref.: https://goo.gl/L7tEr6

- Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, Abu-Rustum N, Darai E. Endometrial cancer. The Lancet. 2016; 387: 1094-1108. Ref.: https://goo.gl/B4M4qx

- Bansal N, Yendluri V, Wenham RM. The molecular biology of endometrial cancers and the implications for pathogenesis, classification, and targeted therapies. Cancer Control. 2009; 16: 8-13. Ref.: https://goo.gl/NLz8Lh

- Llobet D, Pallares J, Yeramian A, Santacana M, Eritja N, et al. Molecular pathology of endometrial carcinoma: Practical aspects from the diagnostic and therapeutic viewpoints. J Clin Pathol. 2009; 62: 777-785. Ref.: https://goo.gl/gxXjZy

- Clarke BA, Gilks CB. Endometrial carcinoma: controversies in histopathological assessment of grade and tumour cell type. J Clin Pathol 2010; 63: 410-415. Ref.: https://goo.gl/bW3JHk

- Talhouk A, McAlpine JN. New classification of endometrial cancers: the development and potential applications of genomic-based classification in research and clinical care. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2016; 3: 14. Ref.: https://goo.gl/5E7ysZ

- Abeler VM, Kjørstad KE, Berle E. Carcinoma of the endometrium in Norway: a histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1992; 2: 9-22. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Y5xguK

- Mendivil A, Schuler KM, Gehrig PA. Non-endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: a review of selected histological subtypes. Cancer Control. 2009; 16: 46-52. Ref.: https://goo.gl/0ZVd1Y

- Cirisano FD, Robboy SJ, Dodge RK, Bentley RC, Krigman HR, et al. Epidemiologic and Surgicopathologic Findings of Papillary Serous and Clear Cell Endometrial Cancers When Compared to Endometrioid Carcinoma. Gynecologic Oncology. 1999; 74: 385-394. Ref.: https://goo.gl/b7Bwuc

- Lobo FD, Thomas E. Type II endometrial cancers: A case series. J Midlife Health. 2016; 7: 69-72. Ref.: https://goo.gl/nNy3pY

- Black C, Feng A, Bittinger S, Quinn M, Neesham D, et al. Uterine Papillary Serous Carcinoma: A Single-Institution Review of 62 Cases. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2016; 26: 133-140. Ref.: https://goo.gl/N67WyA

- Hamilton CA, Cheung MK, Osann K, Chen L, Teng NN, et al. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 642-646. Ref.: https://goo.gl/hWmQNS

- JSOG. Annual report ofendometrial cancer, 2008. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Jpn. 2010; 62: 853-876.

- Hoang LN, McConechy MK, Kobel M, Han G, Rouzbahman M, et al. Histotype-genotype correlation in 36 high-grade endometrial carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013; 37: 1421-1432. Ref.: https://goo.gl/T3fx7t

- Lax SF, Kurman RJ. A dualistic model for endometrial carcinogenesis based on immunohistochemical and molecular genetic analyses. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1997; 81: 228-232. Ref.: https://goo.gl/wwuzjc

- McConechy MK, Ding J, Cheang MC, Wiegand KC, Senz J, et al. Use of mutation profiles to refine the classification of endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol. 2012; 228: 20-30. Ref.: https://goo.gl/7Hw7Hl

- Alvarez T, Miller E, Duska L, Oliva E. Molecular profile of grade 3 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma: is it a type I or type II endometrial carcinoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2012; 36: 753-761. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ShXOXw

- Coenegrachts L, Garcia-Dios DA, Depreeuw J, Santacana M, Gatius S, et al. Mutation profile and clinical outcome of mixed endometrioid-serous endometrial carcinomas are different from that of pure endometrioid or serous carcinomas. Virchows Archiv. 2015; 466: 415-422. Ref.: https://goo.gl/RkRpLF

- Alkushi A, Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Gilks CB. High-grade endometrial carcinoma: serous and grade 3 endometrioid carcinomas have different immunophenotypes and outcomes. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010; 29: 343-350. Ref.: https://goo.gl/4FLcP1

- Santacana M, Maiques O, Valls J, Gatius S, Abo AI, et al. A 9-protein biomarker molecular signature for predicting histologic type in endometrial carcinoma by immunohistochemistry. Hum Pathol. 2014; 45: 2394-2403. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ZC2fPF

- Kumar MB, Hart WR. Metastases to the uterine corpus from extragenital cancers. A clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Cancer 1982; 50: 2163-2169. Ref.: https://goo.gl/soUMd6

- Ring KL, Bruegl AS, Allen BA, Elkin EP, Singh N, Broaddus R. Hereditary cancer panel testing in an unselected endometrial carcinoma cohort. Gynecologic Oncology 2016; 141:10-11. Ref.: https://goo.gl/QIZTXC

- Ring KL, Bruegl AS, Allen BA, Elkin EP, Singh NU, et al. Broaddus R. Germline multi-gene hereditary cancer panel testing in an unselected endometrial cancer cohort. Modern Pathology 2016; 29: 1381-1389. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Uxjj44

- Walsh CS, Blum A, Walts A, Alsabeh R, Tran H, et al. Lynch syndrome among gynecologic oncology patients meeting Bethesda guidelines for screening. Gynecol Oncol 2010; 116: 516-521. Ref.: https://goo.gl/mhtJai

- Hampel H, Frankel W, Panescu J, Lockman J, Sotamaa K, et al. Screening for Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) among endometrial cancer patients. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 7810-7817. Ref.: https://goo.gl/U0NrcH

- Lu KH, Schorge JO, Rodabaugh KJ, Daniels MS, Sun CC, et al. Prospective determination of prevalence of lynch syndrome in young women with endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 5158-5164. Ref.: https://goo.gl/pec1c3

- Ketabi Z, Mosgaard BJ, Gerdes AM, Ladelund S, Bernstein IT. Awareness of endometrial cancer risk and compliance with screening in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2012; 120: 1005-1012. Ref.: https://goo.gl/TETYXw

- Gruber SB, Thompson WD. A population-based study of endometrial cancer and familial risk in younger women. Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study Group. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1996; 5: 411-417. Ref.: https://goo.gl/x18XFJ

- Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 919-932. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Ek9tjL

- Barrow E, Hill J, Evans DG. Cancer risk in Lynch Syndrome. Fam Cancer 2013; 12: 229-240. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1YWbL3

- Hampel H, Frankel W, Panescu J, Lockman J, Sotamaa K et al. Screening for Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) among endometrial cancer patients. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 7810-7817. Ref.: https://goo.gl/xIAAKx

- Hampel H, Panescu J, Lockman J, Sotamaa K, Fix D, et al. Comment on: Screening for Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer) among Endometrial Cancer Patients. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 9603. Ref.: https://goo.gl/tJtwum

- Moline J, Mahdi H, Yang B, Biscotti C, Roma AA, et al. Implementation of Tumor Testing for Lynch Syndrome in Endometrial Cancers at a Large Academic Medical Center. Gynecol Oncol 2013; 130: 121-126. Ref.: https://goo.gl/lXddqC

- Egoavil C, Alenda C, Castillejo A, Paya A, Peiro G, et al. Prevalence of Lynch Syndrome among Patients with Newly Diagnosed Endometrial Cancers. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e79737. Ref.: https://goo.gl/q2vFt6