Design and Validation of a Research Motivation Scale for Peruvian University Students (MoINV-U)

- 1Grupo de Investigación Avances en Investigación Psicológica, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Lima, Peru

- 2Facultad de Derecho y Humanidades, Universidad Señor de Sipán, Chiclayo, Peru

- 3Grupo de Investigación P53, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Escuela de Medicina Humana, Universidad Peruana Unión, Lima, Peru

The aim of the study was to design and validate a research motivation scale for Peruvian university students (MoINV-U). Instrumental design study where a scale of 16 items distributed in two factors (willingness and interest) was designed and validated. A total of 2,249 university students (59.2% women) participated in the study. To analyze the evidence of content-based validity, Aiken’s V coefficient was used; for construct validity, confirmatory factor analysis was used, and reliability was studied through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The items received a favorable evaluation (Aiken’s V > 0.70). The goodness-of-fit indices were adequate (CFI = 0.959, TLI = 0.950 and RMSEA = 0.080), likewise, the correlation between factor 1 and 2 was significant (p < 0.05), evidence of validity was obtained based on the relationship with other variables with measures of academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination and the reliability was acceptable (α = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.86–0.88). The MoINV-U scale is a tool that presents evidence of validity and reliability for the sample of Peruvian university students.

Introduction

After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the generation of scientific knowledge as from the first weeks of 2020 began at an unprecedented accelerated rate (Zayas et al., 2020). This allowed for the development of vaccines and prevention strategies with which it was possible to reduce infection rates and deaths, even those by the new variants, in addition to reinvigorating the economy through technological innovation (Abreu-Hernández et al., 2020).

Despite this remarkable performance and the active participation of Latin American researchers during the health emergency, the existing gap between Latin American production and that of first world countries is still a pending matter (Chinchilla-Rodríguez et al., 2015); This is the case of Peru, especially, a country that is trying to boost its health scientific production (Mamani-Benito, 2021). Among the limiting factors, we can find scarce public and private investment in scientific-technological activities, a low number of professionals dedicated to research, and a lack of motivation to conduct research (Tan, 2021).

Regarding motivation study, there are various theories explaining the issue from multifarious perspectives (educational, work, and clinical, among others). This research is guided by the hypotheses raised by two theoretical models: First, the self-determination theory (SDT), which proposes the existence of two types of motivation (intrinsic and extrinsic) (Ommering et al., 2021), focusing its conceptualization toward the exploration of energy generated in human needs as well as the direction with regard to the processes giving sense to external and internal stimuli. This way, actions are oriented toward the satisfaction of needs (Stover et al., 2017). Second, Atkinson (1964) and McClelland (1985) achievement-based motivational theory, which proposes an action- and task-oriented model. In other words, it is based on creating an expectation of favorability as a consequence of achievement, maintaining persistence in the compensation of pending tasks, and creating initiatives in different contexts and problems. Thus, its conceptualization includes aspects from the SDT theory—that motivation is a process guiding efforts regarding persistence, direction, and intensity in the goals set by an individual (Robbins, 2004).

This is why this construct has an important connotation within the university environment, especially within research processes, in which the academic achievement motivation (Becerra and Morales, 2015) has proven to be an important variable at the moment of conducting scientific research, because carrying out projects, writing articles, and presenting results in field conferences requires an internal state that activates and guides the behavior of a person toward certain goals or purposes.

Thus, it is possible to infer that the purpose of forging graduates with a mindset oriented toward scientific production requires commitment and interest in the research practice from the very beginning of their university studies, where variables such as personality (Mamani-Benito and Apaza, 2019) and motivation play a determining role to achieve not only the promotion of student scientific production but also to expand this practice to the context of their professional development (Amgad et al., 2015).

At this point, considering the abovementioned theoretical aspects, the authors define research motivation as the inner state that activates, leads, and guides the interest and/or attitude of a student toward activities related to scientific research, giving rise to the impulse needed to have the determination and perseverance to achieve scientific production-related goals.

Nowadays, although several studies have addressed the study of motivational factors for research and the reasons to conduct research in Latin America (Ortuño-Soriano et al., 2013; Veytia and Contreras, 2018), detailed information on the validation process of the instruments employed is lacking. For example, there is no evidence gathered on dimensionality through factor analyses processes.

Meanwhile, Deemer et al. (2010) designed and validated an instrument in English to measure research motivation in professionals from different disciplines in the United States and Canada, obtaining evidence supporting a three-factor model: extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, and failure avoidance. Their instrument was translated and adapted for its use with postgraduate students in China (Lili et al., 2012) and to measure research motivation in Iranian teachers (Hosseini and Bahrami, 2020) in addition to American students who were part of a doctorate program in psychology (Mayer, 2012).

The results of the psychometric analyses of these studies corroborated the existence of the three factors in the original version. However, the research conducted by Leech and Haug (2016), which aimed at proving whether the data collected from a sample of American university teachers fit the model described by Deemer et al. (2010), showed that a new four-factor model provides a better fit, considering the factors failure avoidance, intrinsic reward-satisfaction, intrinsic reward-happiness, and extrinsic reward.

Another measuring instrument that has an objective similar to that of this study is the one developed by Lin et al. (2014), who created an inventory to assess motivation to write research articles among Taiwanese postgraduate students. Its internal structure, explored through factor analysis techniques, is made up of five factors: interest value, usefulness value, cost, connectivity value, and ability self-concept. Although these instruments constitute valuable proposals that have received empirical support, their items focus on measuring research motivation in professionals or individuals who have already completed undergraduate programs, for whom aspects such as working cooperatively with researchers from other countries, achieving scientific accomplishments, or earning respect from their colleagues are relevant motivation indicators.

Thus, this study designs and validates a Research Motivation Scale for Peruvian University Students (MoINV-U, Spanish abbreviation).

Materials and Methods

Design

The design is instrumental and cross-sectional, as the measurement scale was designed and validated considering the main psychometric properties (Ato et al., 2013).

Population and Sample

The target population included Peruvian undergraduate university students who were studying both at private and public universities—the latter is funded by the National Superintendency of University Education (SUNEDU, for its Spanish acronym), an entity ensuring quality conditions, including research, in Peruvian schools.

The study involved 2,249 Peruvian university students from the three regions of the country (Coast, Highlands, and Jungle); 1,332 were women (59.2%), whose ages ranged between 16 and 38 (Mean = 20.8 years; SD = 4.1) of whom 70.7% studied in private universities and 27.2% at the School of Health Sciences. These university students were selected through non-probability purposive sampling, and considered (1) being enrolled in any Peruvian university; (2) being undergraduate students, regardless the semester, school, or educational institution; and (3) having given their consent as inclusion criteria.

Instrument Design

The study was conducted in several stages. First, existing literature on this topic was reviewed using SciELO electronic bookshop, the Scopus database, and Google Scholar search engine. Second, indicators associated with theoretical aspects of motivation were collected, in this case, Kuhl’s SDT (1987) and Atkinson (1964) and McClelland (1985) achievement-based motivational theory, specifically, who agree that a motivational theory explores the will and interest observed during motivational processes. Third, research motivation was defined, followed by the fourth stage during which, after a thorough examination of the scientific literature, together with the experience of the present authors, eight indicators were proposed for the will factor (initiative and learning for the use of scientific databases, research methodology, information managers, scientific writing, involvement in research groups, writing styles, scientific article publishing process, and self-assessment of the potential of their own research ideas) and eight indicators were set for the interest factor (research training, prioritization of different tasks involving research, literature review, the researcher’s lifestyle, contribution to the scientific community, economic benefits arising from research, social problem solving, scientific production). Finally, 16 items were drafted (one per indicator), using a two-dimensional distribution: will and interest, with 5 point Likert-scale response options, values ranging from 1 (Completely disagree) to 5 (Completely agree). Following that, with the help of 10 experts (lecturers and researchers in the Health Sciences field), the survey was validated to define the clarity, relevance, and representativeness of the test content.

Likewise, to analyze the validity evidence based on the relationship with other variables, the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale in Peruvian University Students was used (ASESPUS, Spanish acronym; Domínguez and Villegas, 2012). It consists of nine items with four response options ranging from never to always. In this study, the internal consistency analysis showed adequate values [α = 0.92 (95% CI: 0.91–0.92)]. The Academic Procrastination Scale (APS; Busko, 1998) was also used in its validated and adapted version for the Peruvian university students (Domínguez and Villegas, 2014). This scale presents two dimensions, which are as follows: Activity procrastination (three items) and Academic self-regulation (nine items) with five response options on an ordinal Likert-type scale (1 = Never to 5 = Always). In this study, APS showed adequate internal consistency [α = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.83–0.86)]. For factor Academic self-regulation, α = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.83–0.86) and for Procrastination, α = 0.79 (95% CI: 0.77–0.80).

Procedure

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Peruana Unión under reference number 2021-CEUPeU-0037. Because of the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, an online form was generated through Google Forms. It was sent to university students through institutional mail and social networks. Before answering the questions, informed consent was obtained, and students were informed of the study goals, with the emphasis that participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed in stages. First, content-based validity was analyzed through Aiken’s V coefficient (with significant values ≥0.70) calculated with the scores assigned by the group of experts (Ventura-León, 2019). Second, a descriptive analysis of the variables was performed. Third, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted after applying Bartlett’s test and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin coefficient (KMO); the unweighted least squares method with prominent oblique rotation and parallel analysis was used to determine the number of factors. Fourth, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed, considering goodness-of-fit indices, that is, Chi-square (χ2), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the incremental fit index (CFI), with minimum values of 0.90 and recommended values greater than 0.95; RMSEA with a minimum value of 0.08 to less and optimum of 0.05 to less; SRMR with a minimum value of 0.08 to less and 0.06 to less as optimum. A reliability analysis was performed on the optimal factorial model using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

The descriptive analyses and EFA were carried out with the FACTOR Analysis 10.1 program, for CFA, the RStudio program and SPSS 26.0 to calculate reliability.

Results

Table 1 shows the results of the evaluation of the 10 experts who analyzed the relevance, representativeness, and clarity of the MoINV-U scale items. It can be seen that the items received a favorable evaluation (V > 0.70). In terms of relevance, it is clear that items 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 13 are more important than the others (V = 1.00; 95% CI: 0.89–1.00). Items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 13 are the most representative ones (V = 1.00; 95% CI: 0.89–1.00), and item 10 is the clearest one (V = 1.00; 95% CI: 0.89–1.00). Moreover, it can be seen that all the values of the lower limit (Li) of the 95% CI are appropriate and all the values of the V coefficient were statistically significant. Thus, the MoINV-U scale reports evidence of content-based validity.

Table 1. Aiken’s V to analyze relevance, representativeness, and clarity of the MoINV-U scale items.

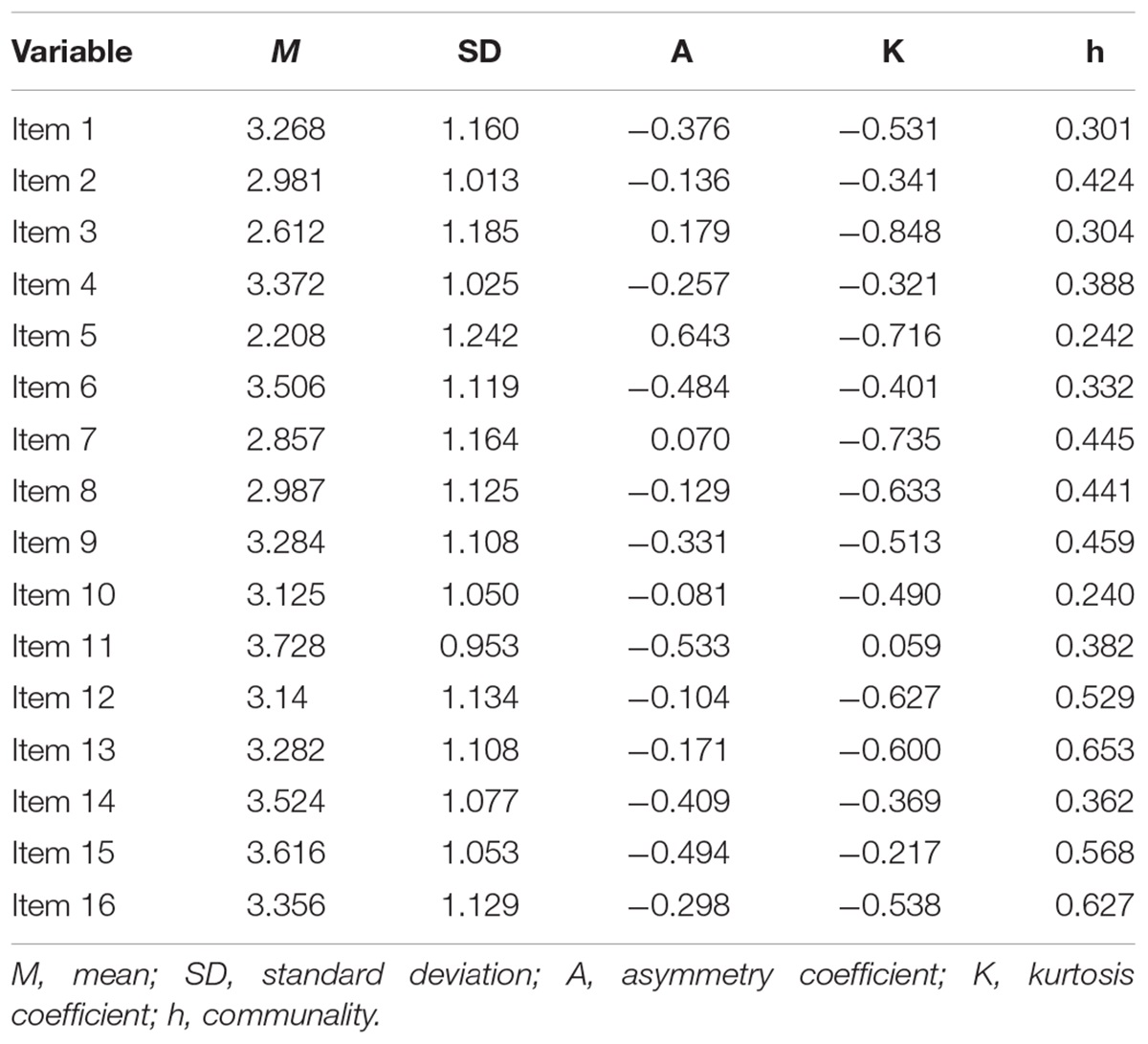

Preliminary Analysis of the Items

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis) of the 16 items of the MoINV-U scale. It is observed that item 15 presents the highest mean score (M = 3.61). The values of skewness and kurtosis do not exceed the range ±1.5 (Pérez and Medrano, 2010). Meanwhile, it can be seen that items 5 and 10 (I joined a research group (scientific organizations, projects, groups, and research seedbeds) to improve my research, and When a professor leaves a research project, I pay more attention to it than to the rest of the tasks) present communality lower than 0.30 and thus are not considered in EFA.

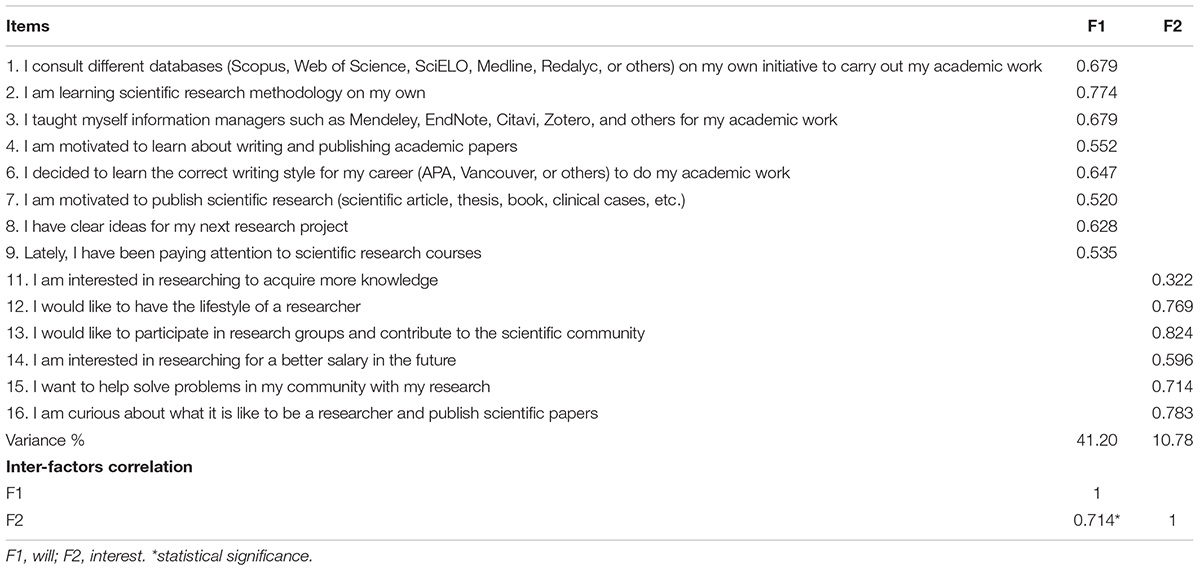

Exploratory Factor Analysis

An EFA was performed after reviewing the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index (KMO = 0.927) and Bartlett’s test (11879.5; gl = 91; p = 0.000), which were significant. The unweighted least squares method with prominent oblique rotation was considered and parallel analysis was used for factor determination, which revealed that there are two factors underlying the 14 items. The rotated solution of the 14 items explains 51.99% of the total variance explained. Factor 1 (Will) explains 41.20% of the variance and Factor 2 (Interest) explains 10.78% of the variance. All items present saturations greater than 0.32 (Table 3).

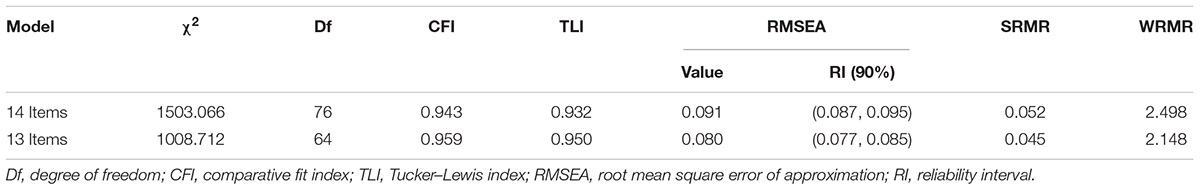

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table 4 shows the CFA, which was used to verify the validity evidence. Moreover, in the internal structure of the MoINV-U scale, the results of the first original model showed adequate fit indices; however, the RMSEA was deficient. Therefore, through the index modification technique, item 11 was eliminated, obtaining a satisfactory two-dimensional factorial structure model. The fit indices show that the proposed model is adequate (χ2 = 1008.712; df = 64; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.959; TLI = 0.950; RMSEA = 0.080; SRMR < 0.05).

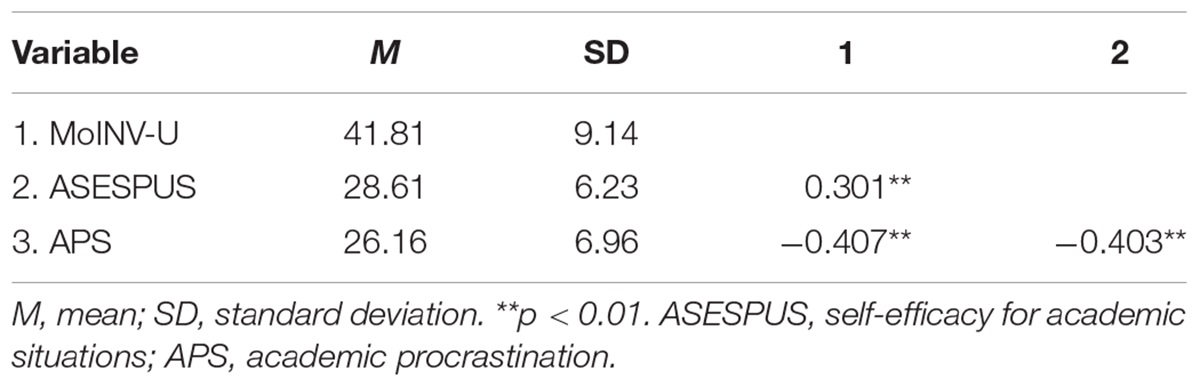

Validity Based on the Relation With Other Variables

Table 5 shows the calculation of the correlation coefficients between MoINV-U, ASESPUS, and APS. It was found that MoINV-U is directly and statistically significantly related to ASESPUS (r = 0.301, p < 0.01). Furthermore, E.M.I. is inversely and statistically significantly correlated with APS (r = −0.407, p < 0.01). In addition, they present a small effect size. The findings show evidence of concurrent validity.

Reliability

The reliability of the scale was estimated with Cronbach’s α coefficient. An acceptable value was obtained for the general scale (α = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.86–0.88). Moreover, for the will factor (α = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.77–0.80) and for the interest factor (α = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.83–0.86), demonstrating that the scale scores are reliable.

Discussion

The importance of teaching research in the university scenario highlights one of the main purposes of the university community, linked to the generation of valid scientific knowledge to solve current problems in societies. Additionally, the priority of the attention in training students has been increased by the regulations in force in the national context, which provide for the development of research proposals as a requirement to obtain academic and professional degrees.

It is in this context that it is necessary to study the variables involved in students’ research action, such as research motivation. Moreover, it is essential to undertake instrumental studies that allow having measurement tools in place to make valid and reliable assessments to address these variables. Thus, this study designs and validates a Research Motivation Scale for Peruvian university students (MoINV-U).

As for content-based validity, through the process of expert judgment, quantified by means of Aiken’s V coefficient, it is confirmed that the items developed are relevant and representative of the behavioral domain of the research motivation construct, obtaining appropriate values in the lower limit of the 95% CI. It is also clear that, according to the judges’ criteria, the items are sufficiently clear to be understood and answered by the study’s target population. Thus, it is shown that the MoINV-U scale reports evidence of content-based validity.

Regarding the validity based on internal structure, prior to the EFA, the communality of the items was evaluated, and it is necessary to eliminate items 5 [I enrolled in a research group (scientific organizations, projects, groups, and research seedbeds)] and 10 (When a professor leaves a research project, I pay more attention to it than to the rest of the tasks), for obtaining values lower than 0.30. This decision was considered after the content and responses to these items revealed that the responses aligned to the lower scores are not exclusive to subjects who present high levels of the measurement construct. Specifically, an affirmative response to item 5 would depend not only on the student’s motivation but also on the opportunities offered by the university of which the student takes advantage.

Then, EFA was performed, using the unweighted least squares method and prominent oblique rotation, and it revealed the existence of two factors underlying the MoINV-U scale items that together explain 51.98% of the common variance, with items with factor loadings above 0.32. A content analysis of the items of the first factor enabled it to be designated as “Will,” referring to the conscious decision to implement activities related to research, while the content analysis of the items of the second factor led to it being designated as “Interest,” considering the cognitive and effective orientation toward topics and tasks related to research. Additionally, CFA made it possible to evaluate the modification indexes of the items, a process through which the decision was made to eliminate item 11, resulting in a two-dimensional factor structure model with optimal fit indexes (χ2 = 1008.712; df = 64; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.959; TLI = 0.950; RMSEA = 0.080; SRMR < 0.05). Thus, the MoINV-U scale presents evidence of validity based on internal structure.

Next, EFA was conducted using the unweighted least squares method and Promin oblique rotation, showing the existence of two factors underlying the items of the MoINV-U scale. A content analysis of the first-factor items allowed establishing the Will denomination, making reference to the conscious decision making to launch research-related activities, whereas the content analysis of the second factor items defined it as Interest, considering the cognitive and affective guidance toward research-related themes and tasks. In addition, CFA allowed for the assessment of the modification indices of the items, a process by which a decision was made to remove item 11, as its errors correlated to the errors of several other items, thus threatening the model’s parsimony. This resulted in a 13-item two-dimensional factor model with optimal adjustment indices.

Even though the results of the dimensionality study on the MoINV-U scale could not be compared with findings from previous studies given its innovating nature, a more detailed analysis of the items and their correlation with the factors they belonged to allow us to identify similarities with factor structures found in other instruments from English-speaking countries. This is the case of the inventory created by Lin et al. (2014), in which one of the factors underlying the motivation construct to write research articles is interest, highlighting indicators related to the incentive and enthusiasm for research-related activities. Thus, the MoINV-U scale presents validity evidence based on the internal structure.

As for validity based on the relationship with other variables, a statistically significant positive relationship was found between the scores of the MoINV-U scale and the ASESPUS scale, which evaluates self-efficacy in the academic context. This finding is compatible with the results of previous research and current theory supporting the usefulness of self-efficacy in predicting motivational outcomes in academic contexts (Schunk, 1995; Husain, 2014). Furthermore, a statistically significant negative relationship was found between scores on the MoINV-U scale and the APS scale, which assesses academic procrastination. This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies corroborating that academic motivation negatively affects academic procrastination (Cerino, 2014; Cavusoglu and Karatas, 2015; Demir and Kutlu, 2018).

In addition, a statistically significant relationship was found in a negative direction between scores on the MoINV-U scale and the APS scale, which assesses academic procrastination. This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies corroborating that academic motivation negatively affects academic procrastination (Cerino, 2014; Cavusoglu and Karatas, 2015; Demir and Kutlu, 2018).

Finally, regarding the assessment of the reliability of the constructed instrument, the internal consistency perspective was adopted, obtaining acceptable indices, both for will and interest factors, thus obtaining acceptable indexes with Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.70, both for the will factor (α = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.77–0.80), and the interest factor (α = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.83–0.86). Therefore, it can be stated that the MoINV-U scale is an accurate measurement instrument. These results are not comparable with prior research yet; as no scale assessing similar constructs in Spanish-speaking countries targeted to university students has been reported, future studies may confirm the results obtained.

This study is not without limitations, the most important one being the lack of segmentation of the sample according to sociodemographic variables of relevance to the study of research motivation, such as sex, type of educational management, or area of training. Therefore, given the limitations reported, it is necessary to replicate this study with a sample of more diverse areas and education levels of university students to broaden the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, it is considered relevant to study the factorial invariance of the MoINV-U scale, according to variables of importance such as sex or area of training. However, we believe that these limitations do not invalidate the study findings, as it is a novel approach that allows us to have a valid and reliable measurement tool through which research motivation in university students is assessed in Latin America.

It is concluded that the MoINV-U scale is a tool that presents evidence of validity and reliability for the sample of Peruvian university students. The main contribution of this study is providing a useful measurement tool that allows the assessment of one of the variables that contributes to the understanding of the acquisition of research skills by university students.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Universidad Peruana Unión. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

RE and OM-B conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. SH-V and SL contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools or data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abreu-Hernández, L. F., Valdez-García, J. E., Esperón-Hernández, R. I., and Olivares-Olivares, S. L. (2020). COVID-19 challenge with regard to medical schools social accountability: new professional and human perspectives. Gac. Mex. 156, 307–312. doi: 10.24875/GMM.20000306

Amgad, M., Tsui, M. M. K., Liptrott, S. J., and Shash, E. (2015). Medical student research: an integrated mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10:1–31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127470

Ato, M., López-García, J. J., and Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 29, 1038–1059.

Becerra, C., and Morales, M. (2015). Validación de la Escala de Motivación de Logro Escolar (EME-E) en estudiantes de bachillerato en México. Innov. Educ. 15, 135–153.

Busko, D. A. (1998). Causes and consequences of perfectionism and procrastination: a structural equation model. Univ. de Guelph 1998:20169.

Cavusoglu, C., and Karatas, H. (2015). Academic procrastination of undergraduates: self-determination theory and academic motivation. Anthropologist. 20, 735–743. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2015.11891780

Cerino, E. S. (2014). Relationships between academic motivation, self-efficacy, and academic procrastination. Psi. Chi. Journal. 19, 156–163.

Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Z., Zacca-González, G., Vargas-Quesada, B., and Moya-Anegón, F. (2015). Latin American scientific output in public health: combined analysis using bibliometric, socioeconomic and health indicators. Scientometrics. 102, 609–628. doi: 10.1007/s11192-014-1349-9

Deemer, E. D., Martens, M. P., and Buboltz, W. C. (2010). Toward a tripartite model of research motivation: Development and initial validation of the Research Motivation Scale. J. Car. Assess. 18, 292–309. doi: 10.1177/1069072710364794

Demir, Y., and Kutlu, M. (2018). Relationships among internet addiction, academic motivation, academic procrastination, and school attachment in adolescents. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 10, 315–332. doi: 10.15345/iojes.2018.05.020

Domínguez, S., and Villegas, G. (2012). Propiedades Psicométricas De Una Escala De Autoeficacia Para Situaciones Académicas En Estudiantes Universitarios Peruanos. Rev. Psicl. 2, 27–93.

Domínguez, S., and Villegas, S. (2014). Procrastinación Académica: validación De Una Escala En Una Muestra De Estudiantes De Una Universidad Privada. Liberabit. Rev. Psicol. 20, 293–304.

Hosseini, M., and Bahrami, V. (2020). Adaptation and Validation of the Research Motivation Scale for Language Teachers. J. Exp. Educ. 2020, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2019.1709036

Husain, U. K. (2014). Relationship between self-efficacy and academic motivation. Internat. Conf. Econ. Educ. Hum. 2014, 10–11.

Leech, N. L., and Haug, C. A. (2016). The research motivation scale: validation with faculty from American schools of education. Internat. J. Res. Dev. 7, 30–45. doi: 10.1108/IJRD-02-2015-0005

Lili, J., Xiu-zhen, F., Min, C., and Liu, Y. (2012). Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Research Motivation Scale: testing in postgraduate nursing students. J. Nurs. Sci. 2012:20.

Lin, M.-C., Cheng, Y.-S., and Lin, S.-H. (2014). Development of a Research Article Writing Motivation Inventory. TESOL Q. 48, 389–400. doi: 10.1002/tesq.164

Mamani-Benito, O. (2021). Rasgo conciencia de la personalidad: factor determinante en la producción científica peruana. Educ. Med. 22:2021.

Mamani-Benito, O. J., and Apaza, E. E. (2019). Rasgo conciencia y actitud hacia la tesis en universitarios de una sociedad científica. Rev. Psicol. 37, 559–581. doi: 10.18800/psico.201902.008

Mayer, C. B. (2012). Research motivation in professional psychology doctoral students: Examination of the psychometric properties of the Research Motivation Scale. Ruston, LA: Louisiana Tech University.

Ommering, B. W. C., van Blankenstein, F. M., van Diepen, M., and Dekker, F. W. (2021). Academic success experiences: promoting research motivation and self-efficacy beliefs among medical students. Teach. Learn. Med. 2021, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1877713

Ortuño-Soriano, I., Posada-Moreno, P., and Fernández-Palacio, E. (2013). Actitud y motivación frente a la investigación en un nuevo marco de oportunidad para los profesionales de enfermería. Index. Enferm. 22:12962013000200004.

Pérez, E. R., and Medrano, L. A. (2010). Análisis factorial exploratorio: bases conceptuales y metodológicas. Rev. Argent. Cienc. Comport. 2, 58–66. doi: 10.32348/1852.4206.v2.n1.15924

Schunk, D. H. (1995). Self-efficacy, motivation, and performance. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 7, 112–137. doi: 10.1080/10413209508406961

Stover, J. B., Bruno, F. E., Uriel, F. E., and Fernández Liporace, M. (2017). Teoría de la autodeterminación: una revisión teórica. Perspect. Psicol. 14, 105–115.

Tan, C. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on student learning performance from the perspectives of community of inquiry. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 10:419. doi: 10.1108/CG-09-2020-0419

Ventura-León, J. (2019). De regreso a la validez basada en el contenido. Adicciones 2019:1160. doi: 10.1080/00221300309601160.Cohen

Veytia, M. G., and Contreras, Y. (2018). Factores motivacionales para la investigación y los objetos virtuales de aprendizaje en estudiantes de maestría en Ciencias de la Educación [Motivational factors to research and virtual learning objects in Maesters students in education sciences.]. RIDE 9, 84–101.

Keywords: motivation, research, university students, validation study, Peru

Citation: Esteban RFC, Mamani-Benito O, Huancahuire-Vega S and Lingan SK (2022) Design and Validation of a Research Motivation Scale for Peruvian University Students (MoINV-U). Front. Educ. 7:791102. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.791102

Received: 10 November 2021; Accepted: 21 February 2022;

Published: 25 April 2022.

Edited by:

Niwat Srisawasdi, Khon Kaen University, ThailandReviewed by:

Chia-Lin Tsai, University of Northern Colorado, United StatesKhalil Gholami, University of Kurdistan, Iran

Copyright © 2022 Esteban, Mamani-Benito, Huancahuire-Vega and Lingan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renzo Felipe Carranza Esteban, rcarranza@usil.edu.pe

Renzo Felipe Carranza Esteban

Renzo Felipe Carranza Esteban Oscar Mamani-Benito

Oscar Mamani-Benito Salomón Huancahuire-Vega

Salomón Huancahuire-Vega Susana K. Lingan1

Susana K. Lingan1