Abstract

The restoration perspective on human adaptation offers a broad view of relations between environment and health; however, it remains underutilized as a source of insight for nature-and-health studies. In this chapter, I start from the restoration perspective in showing ways to extend theory and research concerned with the benefits of nature experience. I first set out the basic premises of the restoration perspective and consider how it has come to have particular relevance for understanding the salutary values now commonly assigned to nature experience. I then discuss the currently conventional theoretical narrative about restorative effects of nature experience and organize some of its components in a general framework for restorative environments theory. Extending the framework, I put forward two additional theories. These call attention to the restoration of resources as held within closer relationships and as held collectively by members of a population. In closing, I consider ways to work with the general framework and further develop the narrative about nature, restoration, and health. The extensions made here raise important considerations for nature preservation efforts, urban planning, health promotion strategies, and ways of thinking about human–nature relations.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

5.1 Introduction

Consider first a broad context for this work: Many people today express alarm at the loss of possibilities for experiencing nature. Their alarm reflects beliefs that the experiences they and their children have in nature contribute to their health. Yet, arguments based on such beliefs have often failed to stop the construction of housing, hospitals, streets, and other structures that serve wants and needs aside from contact with nature. Populations will continue to grow and concentrate in urban areas over the coming decades (United Nations, 2019), and this will drive further loss of possibilities for experiencing nature insofar as other wants and needs continue to receive higher priorities.1

As a counterweight to this trend, research has arguably made it more difficult to disregard arguments for protecting natural settings as public health resources. Many epidemiological studies have found more green space near an urban residence to be associated with societally significant outcomes like less psychological distress (Astell-Burt, Feng, & Kolt, 2013), better cognitive development (Dadvand et al., 2015), and lower risk of future psychiatric disorders (Engemann et al., 2019). Other studies have described similarly salutary values of living near and visiting seashores and other blue spaces (Wheeler, White, Stahl-Timmins, & Depledge, 2012; White et al., 2010, 2019; White, Alcock, Wheeler, & Depledge, 2013). Such findings encourage efforts to ensure ample possibilities for contact with nature while trying to satisfy other wants and needs (Coutts, 2016; Lee, Williams, Sargent, Williams, & Johnson, 2015; Lindal & Hartig, 2015). The epidemiological research thus supports an integrated approach to societal sustainability that addresses its psychological, social, and cultural aspects together with its ecological aspects (Griggs et al., 2013; United Nations, 2015).2

Other research has shed light on the processes that could engender nature-health associations. In line with long-standing ideas in public health, early studies in environmental psychology (Kaplan, 1973; Ulrich, 1979), human geography (Appleton, 1975/1996), outdoor recreation (Driver & Knopf, 1976), and other fields helped to lay the foundations for understanding how nature experience can prove beneficial. Guided by the theories that subsequently coalesced, many experiments have shown that visits to parks and other seemingly natural settings can counter maladaptive rumination (Bratman, Hamilton, Hahn, Daily, & Gross, 2015), reduce anger and sadness (Bowler, Buyung-Ali, Knight, & Pullin, 2010), improve working memory and cognitive flexibility (Stevenson, Schilhab, & Bentsen, 2018), and produce other short-term benefits to a greater degree than ordinary outdoor built settings in an urban context. Such experimental evidence regarding the plausibility of causal mechanisms has encouraged the assumption that repeated contacts with nature cumulatively engender significant health benefits. That assumption motivates much of the research and practice in the area (cf. Hartig, 2007a).

In this chapter, I will build on traditions of inquiry within environmental psychology and allied disciplines to consider processes by which nature experience engenders health benefits. I start from a particular perspective on adaptation as a superordinate process joining people and the environment. This perspective focuses on one aspect of adaptation: the restoration of depleted adaptive resources. The restoration perspective is well represented in research on nature and health, and for good reason. Restoration has long stood out as an important theme in motives for visits to natural areas (Home, Hunziker, & Bauer, 2012; Knopf, 1983, 1987). In keeping with that motivational theme, forms of restoration are focal concerns for two seminal theories about psychological processes through which people benefit from nature experience (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Ulrich, 1983). Ample evidence has affirmed that restoration constitutes a pathway from nature experience to health (Hartig, Mitchell, de Vries, & Frumkin, 2014; Health Council of the Netherlands, 2004). Accumulating evidence also points to ways in which expected and realized restoration work together with other pathways between nature and health, including physical activity (Mitchell, 2013; Pretty, Peacock, Sellens, & Griffin, 2005; Staats, Kieviet, & Hartig, 2003) and neighborhood social cohesion (Dzhambov, Hartig, Markevych, Tilov, & Dimitrova, 2018; Kuo, Sullivan, Coley, & Brunson, 1998). In brief, the restoration perspective has fundamental relevance for nature-and-health studies.

Yet, despite this fundamental relevance, much of the potential of the restoration perspective remains unrecognized. To help remedy this neglect, in this chapter I will indicate additional ways to draw from it as a source of insight for theory and empirical research. In the following, I first set out the basic premises of the restoration perspective and consider how it has come to have particular relevance for understanding the benefits of nature experience. I then consider research that has approached restoration as a set of processes through which nature experience can engender health benefits. In doing so, I focus on some of the main components of what has become a conventional theoretical narrative about restorative effects of nature experience, organized in a general framework for restorative environments theory. Extending the general framework, I then put forward two additional theories. These call attention to the restoration of resources as held within closer relationships and as held collectively by members of a population. In closing, I consider ways to work with the general framework and further develop the narrative about nature, restoration, and health, with a view to implications for nature preservation efforts, urban planning, health promotion strategies, and ways of thinking about human–nature relations.

5.2 The Restoration Perspective: Basic Premises and Particular Relevance

The ability of individuals to successfully adapt in the face of environmental demands has long been a major concern in environmental psychology and allied disciplines. Grounded in evolutionary thought, this concern for behavior motivated by the goal of individual survival is central to those areas of research within what Saegert and Winkel (1990) refer to as the adaptive paradigm. Those research areas can be conveniently framed in terms of stress, coping, and restoration. They complement each other; they deal with necessarily related aspects of adaptation, but they differ in their focus. Research on stress has focused on the environmental demands that challenge adaptation and the physiological, psychological, and social consequences of efforts to face those demands (Evans & Cohen, 1987). Research on coping has focused on the physiological, psychological, and social resources people draw upon to meet environmental demands, and on the different strategies they apply when doing so (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Research on restoration has focused on processes by which people restore psychophysiological and cognitive resources that they have depleted while contending with demands, and on components of environmental experience that support the restoration of depleted resources (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Ulrich, 1983).

Each of these three areas of inquiry builds on a distinctive set of theoretical and practical premises, and each set of premises constitutes a particular perspective on adaptation as a fundamental aspect of human–environment relations (cf. Hartig, 2001). The theoretical premise of the stress perspective is that when people face continuously heavy demands, adaptation can fail, as reflected in poor health (Cohen, Evans, Stokols, & Krantz, 1986; Evans, 1982). The practical premise then refers to ways to prevent that failure through interventions that reduce demands. In contrast, the theoretical premise of the coping perspective is that people can meet even heavy demands over long periods if they have sufficient physical, psychological, social, and material resources (Antonovsky, 1979; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The practical premise then refers to ways to help people more easily maintain adaptation by making resources more readily available to them or by helping them to make better use of those resources already available. In turn, the theoretical premise of the restoration perspective acknowledges that people can have ample protection from unavoidable demands as well as ample coping resources, and yet still need periodic restoration, particularly insofar as the resources held by or between individuals commonly get depleted in the course of everyday activities (Hartig, 2004, 2017). The practical premise then refers to ways to enhance opportunities for people to restore depleted resources more easily, quickly, and completely. The different premises are summarized in Table 5.1 (cf. Hartig, 2008; Hartig, Bringslimark, & Patil, 2008; Von Lindern, Lymeus, & Hartig, 2017).

Human culture has deep roots in each of these three perspectives on adaptation, exemplified by the ways in which hominid apes organize their nest building activities to serve basic needs for sustenance, safety, sleep, social connection, and sanitation (James, 2010). These cultural roots have profound implications for the present discussion of restoration through nature experience; as part of human evolution, conceptions of “nature” and what is “natural” have evolved in relation to artificial features of the environment that resulted from efforts guided by one or more of the three perspectives (cf. Hartig & Evans, 1993). Across many millennia, people have taken myriad steps to protect themselves from environmental demands, to gain access to resources for coping, to better use available resources, to create new resources, and to preserve, create, and enhance opportunities for restoration. In doing so, they have developed increasingly complex technologies for housing, food production, sanitation, transportation, communication, recreation, health care, and so forth to serve their needs and wants. Those needs and wants have grown and complexified in tandem with growth in populations and the articulation of societies. In many societies, as more people could better satisfy their needs and wants in emerging urban contexts, and fewer stayed in rural contexts to secure food and materials for the population, much of what now gets viewed as “nature” came to be regarded less as the environmental settings in which to perform work and more as settings that support recreational and restorative activities (cf. Mercer, 1976). Within these long-running processes of population growth, socio-technical development, rural–urban migration, et cetera, popular conceptions of “nature” got shaped in opposition to conceptions of the “urban” that for more and more people encompassed conditions of everyday life that led them to need restoration, such as work in harsh settings and noise and crowding on busy streets (cf. Hartig, 1993).

With this coarse sketch, I do not mean to assert that such a conceptual opposition between the natural and the urban is somehow a complete description of actual circumstances, applicable to all areas identified as natural or urban across all scales and societal contexts. An urban area is after all situated within the natural environment considered on some scale, with sun above, sky around, soil below, water running through in various ways, and diverse non-human species going about their business, day and night. Moreover, humans in cities reproduce and perpetuate other natural processes as do other species in habitat they have selected and shaped.

Further, I do not mean to assert that a conceptual opposition of the natural and the urban maps perfectly onto experiences of restoration and stress. The natural environment continues to impose demands, some terrible, as with tornadoes and catastrophic earthquakes (that can reach into the largest urban areas), and some minor, as with irritating mosquitoes (that can disturb the peace found in an otherwise pleasant park). And for their part, towns and cities offer many possibilities for restorative experiences aside from those afforded by their green spaces, as in comfortable homes (Hartig, 2012), pleasant cafes (Staats, Jahncke, Herzog, & Hartig, 2016), and museums (Kaplan, Bardwell, & Slakter, 1993).

Rather, in sketching the evolution of this conceptual opposition of the natural and the urban, I want to shed light on reasons why the restoration perspective has come to have particular relevance for understanding salutary values attached to contemporary nature experience. Put simply, its relevance owes in large part to the probabilities of people having particular kinds of experiences in particular activities in particular settings at particular times. The “nature” of concern in such situations is not only some set of objectively measurable biological, physical, visual, or other attributes of the environment that might have effects on functioning and health understandable entirely in isolation from other aspects of the circumstances in which people live. Rather, the ways in which this “nature” figures in human functioning and health need consideration in light of the broader social ecology in which its various positively and negatively evaluated attributes contrast with those of other settings within and across which individuals, groups and populations have organized their activities and distribute their time (cf. Hartig, Johansson, & Kylin, 2003; Heft & Kyttä, 2006; von Lindern, 2015). The various settings in such a social ecological system are more or less likely to support particular activities and experiences, and they accordingly acquire meanings, individual and shared, that reflect on the activities and experiences they normally and predictably support. Differences in meanings emerge as people move among settings, in keeping with changing needs, imperatives, and goals. Patterns of movement and related meanings get reinforced and shaped, often intentionally, as through advertising for different recreational activities and the locations for them (e.g., Mercer, 1976). With the concentration of growing populations and their productive activity in urban areas, an increasingly prevalent pattern of movement involves leaving the built settings where the ordinary demands of life are situated for seemingly natural settings where people can gain distance from everyday tasks and worries, engage with positive aspects and affordances of the environment, and so satisfy needs for restoration. This pattern of movement can manifest on multiple spatial, temporal, and social scales, reflecting the restoration needs involved and the opportunities available, as with a solitary person walking in a near-home park after a trying day at work, or a couple spending a day at the beach after missing each other during the work week, or related families regularly coming together from distant parts of a country to enjoy preferred activities in a national park during their annual summer vacations. As with meanings attached to “nature” and “urban” of themselves, labels and meanings get attached to the patterns of movement that link them and the time spent within them; witness expressions like “getting out of town for the weekend” and “going on vacation” (see Löfgren, 1999). Thus, as part of a sociocultural evolutionary process that has involved change in the likelihood of activities and experiences tied to particular settings and of movements between particular settings, conceptions of “nature” have increasingly become linked with restoration motives, memories, and meanings while conceptions of the “urban” have gotten grounded in the demands that increasing numbers of people face in their everyday lives.3

This account of the particular relevance of the restoration perspective for nature-and-health studies aligns the concerns of the adaptive paradigm with concerns of the two other research paradigms within which it is nested, as described by Saegert and Winkel (1990). Inquiry within the opportunity structure paradigm seeks to understand recurring patterns of behavior within and across settings that have spatio-physical, temporal, and social characteristics suited to programs of activities that serve the pursuit of particular needs and goals. Inquiry within the sociocultural paradigm addresses the individual as a social agent who can read, create, and contest meanings in the environment, and it approaches the challenge of survival “not as an individual concern [as in the adaptive paradigm], but as a problem for the social structure within which the individual is embedded, whether it be family, neighborhood, nation or even world society” (p. 457). Although Saegert and Winkel focus on environmental psychology in their account, they make clear that the three paradigms do not lie wholly within environmental psychology, but rather encompass areas of research activity that it shares with other disciplines, including anthropology, geography, gerontology, history, and sociology. Reaching across the different research paradigms and across disciplines, I assume that a person’s or group’s experience of some environmental feature or setting taken to be natural occurs within a particular historical, societal, and cultural context, as do the physiological, psychological, interpersonal, and social processes carried along in their experience and the various consequences generated by those processes, including cumulative health benefits. As knowledge of those processes and their consequences gets more widely disseminated, it shapes the expectations and behaviors of others in the same and subsequent generations, carrying the sociocultural evolutionary process further.4

5.3 Restorative Benefits of Nature Experience: The Conventional Theoretical Narrative

I have argued that the restoration perspective has particular relevance for understanding the salutary values of nature experience. This relevance increasingly gets “built in,” as an emergent and still evolving conceptual distinction between built/urban and natural settings increasingly gets linked probabilistically with experiences of depletion versus restoration, concomitant to the concentration of populations and productive activities in urban areas. For more and more people, “nature” has become an environmental setting or context into which they might move to restore resources after facing their ordinary demands in relatively built urban settings. However, although escape from mundane stressors in search of restoration has long been recognized as an important theme among motivations for visits to natural areas (e.g., Knopf, 1983, 1987; Mercer, 1976; Olmsted, 1870), the broader health implications of restoration through nature experience remained little studied until relatively recently.

A major impetus to intensified study came with the development and dissemination of two theories that proposed psychological mechanisms by which nature experience can engender restorative benefits: Stephen and Rachel Kaplan’s attention restoration theory and Roger Ulrich’s psycho-evolutionary theory. Their development can be traced through publications by their respective authors from the 1970s onward (e.g., Kaplan, 1973, 1978, 1983, 1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1982, 1989; Ulrich, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1983, 1993; Ulrich et al., 1991). Psycho-evolutionary theory conventionally gets referred to as stress recovery theory or stress reduction theory, and I will use the acronym SRT to reflect these naming conventions, which identify the restorative process itself, as with attention restoration theory (ART). Separately or together, SRT and ART inspired early true and quasi-experimental studies which found that outdoor environments and environmental imagery with prominent trees, vegetation, and other seemingly natural features appeared to better serve restoration than outdoor environments and environmental imagery dominated by buildings, streets, car traffic, and other urban features. Some of the benefits, like better proofreading performance, better inhibition of Necker Cube pattern reversals, and better serial recall were taken as evidence of attention restoration (e.g., Hartig, Mang, & Evans, 1991; Kuo & Sullivan, 2001; Tennessen & Cimprich, 1995). Other benefits, like reduced fear, anger, and systolic blood pressure were taken as evidence of stress recovery (Ulrich, 1979, 1981; Ulrich et al., 1991). Findings regarding the emergence and then dissipation or persistence of such effects during and after time in a natural setting reflected on the possibility that stress recovery and attention restoration could run together (Hartig, Evans, Jamner, Davis, & Gärling, 2003; cf. Ulrich et al., 1991). Such early evidence regarding the operation of plausible causal mechanisms provided support for the first large-scale epidemiological studies to uncover associations between the amount of residential green space and health outcomes (de Vries, Verheij, Groenewegen, & Spreeuwenberg, 2003; Maas, Verheij, Groenewegen, de Vries, & Spreeuwenberg, 2006; Mitchell & Popham, 2007, 2008). These studies could take their findings to reflect, at least in part, on cumulative benefits of repeated restorative experiences.

Aside from this background, I do not intend to say more here about the historical development of research on nature and health (see Hartig et al., 2011) or the now extensive epidemiological literature on health values of urban green space and other settings for contact with nature (for reviews, see e.g., Frumkin et al., 2017; Gascon et al., 2016; Kabisch, van den Bosch, & Lafortezza, 2017; Markevych et al., 2017; Rojas-Rueda, Nieuwenhuijsen, Gascon, Perez-Leon, & Mudu, 2019; for reviews of reviews, see Hartig et al., 2014; van den Bosch & Ode Sang, 2017). Instead, I will discuss the narrative about restorative effects of nature experience built around ART and SRT. I first explain why I refer to it as the conventional narrative, and why it has many variants. I then organize some of its components in a general framework for restorative environments theory. This will help to indicate some of the ways in which nature-and-health studies and research on restorative environments can look beyond the conventional narrative to realize more of the potential of the restoration perspective.

5.3.1 Why Refer to a “Conventional Theoretical Narrative”?

To begin with, consider what I mean by “theoretical narrative” here. Scientists can represent “theory” in quite different ways. Some may present a theory as “a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by a vast body of evidence” (Institute of Medicine, 2008, p. 11). As an example, “the theory of evolution is supported by so many observations and confirming experiments that scientists are confident that the basic components of the theory will not be overturned by new evidence” (p. 11).

This characterization would distinguish a scientific theory as a reliable account of the real world. Not incidentally, reference to “the theory of evolution” in the quotation above could therefore give the impression that scientists have settled on a single formulation; however, many scientists would quickly disavow that impression (as the authors of the quotation above do later in their text). Although scientists agree on the “basic components” of evolutionary theory, like the significance of natural selection, that body of theory encompasses numerous complexities and contrasting formulations concerned with, for example, the sensitivity of different types of biological selective mechanisms to environmental change (e.g., Catalano et al., 2012, 2018; Catalano & Bruckner, 2006; Catalano, Saxton, Gemmill, & Hartig, 2016; Catalano, Zilko, Saxton, & Bruckner, 2010) and related questions about the time needed for populations to adapt biologically to environmental change (for a popular account, see Zuk, 2013). For such reasons, some scientists prefer a definition of theory that differs from the kind of characterization above. Consider the definition offered by the sociologist Hannu Ruonavaara (2018) for a similarly large body of theory also of relevance here:

Social theory: A discourse that consists of a set of linked (a) concepts and (b) propositions to be used for hypothetical (i) redescription, (ii) explanation, and (iii) interpretation of some set of phenomena, relations, and processes (p. 181; italics in original).5

Ruonavaara’s definition situates the contents of a body of theory within an ongoing discourse or exchange with particular types of actions: redescription, explanation, and interpretation. It thus acknowledges that theory remains fluid and “unsettled” as the discourse continues. It remains open, for example, to influences from other areas of research, and to the influence of observations of change in the phenomena of interest. Such change can follow with change in the surrounding sociocultural circumstances, for example, those which influence the ways in which people encounter, engage with, understand and value “nature.”

Implicitly, this definition allows for the emergence of particular ways of telling about the contents of theory, that is, a narrative about theory that applies some logical structure in presenting its different components and links among them. Whether it focuses on a single formulation (a theory) or multiple contrasting formulations (theories) within a body of theory (e.g., restorative environments theory), the narrative may also include an account of some problem in need of solution. This provides a context for the phenomena of interest and helps to establish the value of theorizing about those phenomena. For example, at the start of this Chapter, I explained that alarm at the loss of possibilities for experiencing nature reflects beliefs that nature experience contributes to health, and that such beliefs have been affirmed by research on health benefits of contact with nature. Many readers will have found this context-setting problem-description familiar; similar ones appear in many other texts on nature and health.

Within restorative environments research, some studies appear to have taken explicit guidance from only one theory. Why then refer to a narrative built around both ART and SRT as “conventional”? I see several reasons to do so. For one, a “two theories” narrative appears in one form or another in many peer-reviewed publications about benefits of nature experience. For example, at the time of writing, two articles, cornerstones of the narrative, have more than 1400 citations each in scientific publications listed in the Web of Science database. With this, they are the first and second most cited articles published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology in its now 40-year history (Kaplan, 1995, and Ulrich et al., 1991, respectively). Importantly, where one of the articles gets cited, the other often also gets cited.6 And here I refer to only two publications; people who engage with the nature-and-restoration topic can base a version of the narrative on more than one publication from the authors of ART and SRT and from others.

Also importantly, many and diverse people convey and shape the conventional narrative. It gets carried along not only by researchers but also by people with whom they might interact within the different communities in which they work and live. Joint representation of the two theories has become a standard feature of textbooks in environmental psychology in multiple languages (e.g., Bell, Green, Fisher, & Baum, 2001; Devlin, 2018; Gifford, 1997; Johansson & Küller, 2005; Steg, van den Berg, & de Groot, 2013). Books in English for an international professional audience (e.g., Cooper Marcus & Barnes, 1999; Coutts, 2016; Nilsson et al., 2011; WHO, 2016) also directly or indirectly invoke ART and SRT in explaining how nature experience can serve health. So too do books for a broader public (e.g., Gerlach-Spriggs, Kaufman, & Warner, 1998; Logan & Selhub, 2012; Louv, 2008; Ottosson & Ottosson, 2006), news articles and opinion pieces that get published on the internet, and communication through other media that have a global reach, as with the film Natura by Pascale d’Erm and Bernard Guerrini (2018).

5.3.2 Variations in the Conventional Narrative

What then is this conventional narrative? The scientific, professional, and popular literatures include numerous variants. Variations in the presentation of the two theories have occurred and will continue to occur for readily understandable reasons. For one, Ulrich and the Kaplans gave somewhat different accounts of SRT and ART over the years, presumably reflecting new insights and how they read the work of others, reacted to reviewer comments, responded to inputs from students and other colleagues, grappled with their own observations, and so on.7

Variations in the conventional narrative have also arisen from the different ways in which other authors have represented ART and SRT. In deciding on what to include in an account and how to include it, authors could have based their choices on a number of considerations. Some would reflect their purposes; simply telling about the outcomes of main concern to the theories requires less elaboration than providing sufficient background to understand the hypotheses they base on the theories and the methods they use to address those hypotheses. Other considerations would include the author’s understanding of what Ulrich, the Kaplans, and/or others wrote or said about ART, SRT, and perhaps other theories, as well as their own experiences and structured observations and matters such as the assumed expertise of the intended audience and limits on the amount of text they could write.

Although I see good reasons for variations in the conventional narrative, I do not mean to suggest that any particular variant is acceptable. Some may reflect misunderstandings about the theories. Consider for example an extension of the narrative implied in a report published by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2016). This report gives brief accounts of SRT and ART in setting out restoration as one among other pathways by which urban green space can serve health. It also states that both theories are “based on the biophilia hypothesis, which postulates that humans have an innate need to affiliate with the natural environment within which they have evolved (Wilson, 1984)” (p. 4). Here the report stands in error. Putting aside whether E. O. Wilson’s writing on biophilia could have provided a substantive basis for ART and SRT, I note that none of his work was cited in the early articulations of those theories, which were published before his initial essay on biophilia (e.g., Kaplan & Talbot, 1983; Ulrich, 1983). The literature indicates that the authors of ART and SRT had already drawn on other sources in making the evolutionary assumptions underlying their theories (see, for example, the references to work by Ardrey in Kaplan, 1972). To verify this point, I wrote to Rachel Kaplan and Roger Ulrich to ask how much influence Wilson’s thinking around biophilia had on the work they did over the years. Both replied that it did not have the influence implied in the WHO report (respective personal communications on January 23 and 27, 2020).

I have used one tiny part of a report to illustrate a problematic elaboration of the conventional narrative that does not correspond to the actual development of the underlying theories. I do not mean to discount the value of the report as a whole. Moreover, I can see how the error could enter. Discussions of the restorative benefits of nature experience now often occur in conjunction with discussions of biophilia, and the two lines of thought can appear related in several ways. These include similarities in their assumptions about the slow pace of human evolution through natural selection; treatment of what now gets distinguished as the natural environment as the setting of human biological evolution; concomitant treatment of the urban environment as poorly suited for human habitation; links between natural settings and positive experience; and shared concerns for protecting good habitat for non-human species as well as for humans. The erroneous attribution to Wilson’s work may simply have followed from the repeated pairing of discussions of biophilia and restorative effects of nature experience, much like the repetition that has made the SRT-ART narrative a conventional one. All of this said, the fact remains: Wilson’s thinking on biophilia did not provide the basis for theorizing about restorative effects of nature experience in SRT and ART. Discourse should select against that notion and select for factually correct elaborations on the origins of the two theories. Those who really want to weave biophilia-thinking into the narrative can instead describe how Ulrich’s work influenced Wilson’s thinking.8 More generally, as the discourse continues, it can select for or against aspects of the theories as articulated by their authors, and also for or against specifications, clarifications, extensions, and other elaborations offered by others, for the theories, and for the encompassing narrative.

5.3.3 Components of the Conventional Narrative

Where does the conventional narrative stand now? Instead of just presenting another textual account of SRT and ART, I will set some of the main components of ART and SRT into a general framework that supports comparisons between them. This will do more to show ways to extend the narrative with new lines of inquiry and so illuminate the further potential of the restoration perspective as a source of insight on nature-health relations. I will not give detailed accounts of ART and SRT, nor will I evaluate the evidence regarding the validity of claims based on those theories. For those who do not have a variant of the conventional narrative committed to memory, I suggest reading the texts by the authors of the theories (e.g., Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan & Talbot, 1983; Ulrich, 1983, 1993; Ulrich et al., 1991) as well as the early texts that contrasted the emerging theories (e.g., Hartig et al., 1991; Hartig & Evans, 1993).9

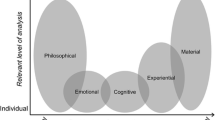

Theories encompassed by the restoration perspective have numerous components that can be included in a general framework to aid comparisons. For example, as theories rooted in the adaptive paradigm, they would represent views of the human condition and human–environment relations that emphasize basic matters of survival. They would accordingly make assumptions about human evolution, with regard, for example, to how natural selection works, its operation on particular aspects of human–environment relations (as in the shaping of habitat preferences), its sensitivity to environmental change, and the limits of adaptability to contemporary conditions. Variations in these components of theories about restorative environments need further attention, but for present purposes I will focus on a smaller set of components, represented by the columns in Table 5.2. These will suffice as starting points for extensions beyond ART and SRT (Hartig, 2004, 2017).

Consider first the resources that could come into play, get depleted, and so need restoration. They take different forms. Psychophysiological resources enable mobilization for action aimed at some demand, whether acute, as when jumping back from a coiled snake, or prolonged, as when working hard to meet a deadline. Cognitive resources include the ability to willfully direct attention to some task at hand while filtering out distractions. These resources are focal concerns of SRT and ART, but they are not the only adaptive resources that might get depleted. Possible new theories about restorative environments could look to other forms of resources, such as the social support a person might receive from family, friends, and acquaintances at home, in the neighborhood, and elsewhere (e.g., Cohen & Syme, 1985).

Consider then the antecedent condition. Because a person depletes various resources in meeting everyday demands, a potential or need for restoration arises regularly. New demands will certainly come along, so the person must secure adequate possibilities for restoration or risk not being able to meet those demands. Insofar as a particular theory focuses on a specific resource or set of resources, it also focuses on the condition of a person who has depleted that resource or set of resources. This could receive consideration as stress or mental fatigue, as in SRT and ART, or as some other form of depletion defined with regard to some other resource, such as a loss of access to instrumental and emotional forms of social support.

Consider then the environmental requirements of the process through which the depleted resource(s) can be restored. Restoration has two basic requirements in this regard. First, the environment permits restoration. Going there, a person gains distance from the demands that caused the given need for restoration, and when there the person does not face new demands that further tax the same depleted resource. Second, the environment promotes restoration. Some demands are not tied to any one place; a person could feel troubled and ruminate over them almost anywhere, further depleting resources. Insofar as an environment has features and affords activities that draw a person’s thoughts away from demands, attracting and holding their attention, the person can better engage with the environment and thus prolong the restorative process(es). This presence of positive features, and not only an absence of negative ones, underlies a basic definition of a “restorative environment” as an environment that promotes, not merely permits, restoration (Hartig, 2004, 2017). Both SRT and ART represent this distinction with their specifications of components of experience though in somewhat different ways. SRT refers to the absence of threat as a permitting feature, one that could also figure in experiences of being away and compatibility as set out in ART; however, the ART concepts encompass more than threats, also including, for example, distance from routine mental contents. With regard to the promotion of faster and more complete recovery, SRT refers to gross structure, moderate depth, moderate complexity, the presence of a focal point, and the survival-serving natural contents a person sees in the environment, which are thought to rapidly evoke positive affect and hold non-vigilant attention, thus blocking negative affect and negative thoughts and so allowing recovery from the physiological arousal characteristic of stress. Some of these features, like gross structure, have commonalities with the bases of the extent construct as defined in ART; greater coherence and scope experienced in the environment can serve to sustain the effortless soft fascination thought to promote rest of the directed attention mechanism. For other resources, and so for other forms of resource depletion, possible theories might augment the descriptions of restorative environments given in SRT and ART and/or specify other kinds of restoration permitting and promoting features. For example, in addition to visually appealing features that would support stress recovery and attention restoration in an individual, the environment might offer distance from the ordinary settings and demands of work and family for both people in a couple, as well as affordances for mutually appreciated activities, including not only the sharing of a restorative interlude while viewing the scenery but also opportunities to have fun, explore, and make discoveries together; to talk about life circumstances; and to share intimacy (for an anecdotal example with links to natural settings, see Pascal, 2016).

Consider then the outcomes. Those measured in experiments anticipate the operation of the presumed causal mechanism during contact with nature versus some comparison condition in a specific situation. For experiments informed by SRT, this has meant expectations of more positively toned affect, as in increased self-reported happiness and reduced anger, as well as reduced activity in one or more of the bodily systems that had previously mobilized for action (e.g., cardiovascular, endocrine, muscular) (e.g., Ulrich et al., 1991; for reviews, see Bowler et al., 2010; Corazon, Sidenius, Poulsen, Gramkow, & Stigsdotter, 2019). For experiments informed by ART, researchers have expected improved performance on tasks that challenge directed attention and perhaps other aspects of executive cognitive functioning, such as working memory and inhibitory control (e.g., Berman, Jonides, & Kaplan, 2008; Schutte, Torquati, & Beattie, 2017; for reviews, see Ohly et al., 2016; Stevenson et al., 2018; Sullivan & Li, Chap. 2, this volume). Similar expectations hold when the same measures are used in quasi-experiments and observational studies to assess cumulative benefits, as with lower chronic stress seen in patterns of cortisol secretion (e.g., Ward Thompson et al., 2012) or better executive cognition seen in standardized tests (e.g., Taylor, Kuo, & Sullivan, 2002; Dadvand et al., 2015). Taking guidance from SRT and/or ART, clinical studies have tested therapeutic interventions in which patients repeatedly perform some activity in a natural setting, and they have reported outcomes such as improved attentional functioning in breast cancer patients (Cimprich & Ronis, 2003), reduced severity of depression (Gonzalez, Hartig, Patil, Martinsen, & Kirkevold, 2010), and the motivation to change a depleting lifestyle following burnout (Sonntag-Öström et al., 2015). The cumulative effects assumption has also guided large-scale epidemiological studies that have reported better health among those with relatively greater amounts of green space near the residence, as reflected in self-reported health (e.g., Astell-Burt, Mitchell, & Hartig, 2014; de Vries et al., 2003) and the incidence of diverse forms of ill health and causes of mortality (e.g., Engemann et al., 2019; Maas et al., 2009). Several studies have also found that greater self-reported being away and fascination appear to mediate between more greenery or green space in the residential environment and distal outcomes like better self-reported health (e.g., Dahlkvist et al., 2016; Dzhambov et al., 2019). Research guided by other possible theories could similarly look to proximal and distal outcomes and hypothesized mediators as fitting with their concerns for other resources, antecedent conditions, and processes. For example, a study concerned with the renewal of bases for sharing of social support could measure variations in mutual trust and appreciation in relationships with relevant others.

Consider then the matters of time. Of temporal parameters that could be used to characterize a potentially restorative exchange between person and environment, it appears that duration has received the most attention, often reflecting constraints imposed by an experimental research setting (i.e., briefer periods for viewing photographs or other simulations in a laboratory, after Ulrich, 1979, and longer periods for walking in some field setting, after Hartig et al., 1991). Related parameters include the time required for different kinds of effects to emerge, the time that different effects persist, and the time allowed for restoration in relation to the time spent in an activity or activities through which the resource(s) in question became depleted (e.g., Hartig, Evans et al., 2003). These parameters help to describe what happens on a single occasion, within a specific situation defined in terms of a person, activity, setting, and time. As noted earlier, those working with ART and SRT have from an early stage also attended to the potential significance of cumulative effects of repeated contact with the natural environment, as through window views at home (e.g., Masoudinejad & Hartig, 2020; Tennessen & Cimprich, 1995), at work (e.g., Kaplan, 1993; Shin, 2007), and in health care settings (e.g., Raanaas, Patil, & Hartig, 2012; Ulrich, 1984); however, matters of frequency, periodicity, and the distribution of time across multiple occasions have not received systematic attention. Such matters would presumably also have significance for other possible theories.

For the theories encompassed by the general framework in Table 5.2, the sequence of columns starts from a particular resource, proceeds to depletion of that resource, and then continues on to an environmental experience that could generate outcomes that reflect on restoration as it may have occurred in a given amount of time. The table thus does more than simply outline components of existing and possible theories; it also represents a way of telling about them. The table shows a narrative structure in which the respective components of a theory and the links among them follow in a sequence revealing the particular process. In other words, for each theory the given row reveals a classic plot line, proceeding from equilibrium (resource availability) through imbalance (resource depletion) to a new equilibrium (through restoration) (Robertson, 2017; Todorov, 1969). By tracing a process across the columns, one can recognize how the concerns of the stress and coping perspectives are necessarily bound together with those of the restoration perspective. Thus, as represented in Table 5.2, the structure of the conventional narrative incorporates an inherent logic of the adaptive paradigm and its subordinate perspectives on the efforts of the individual to survive.

5.4 Restorative Benefits of Nature Experience: Extending the General Framework

To this point, I have argued that the restoration perspective has particular “built in” relevance for understanding the salutary values of nature experience, and I have highlighted some of the main components of a conventional theoretical narrative about restorative benefits of nature experience. I organized those components in a general framework, which I also used to point out the possibility of constructing theories concerned with adaptive resources and restorative processes other than those in focus with SRT and ART. To exemplify the utility of the framework in this respect, I began to sketch a theory concerned with the loss of access to social support as an antecedent condition from which an individual might need to restore.

Now, toward extending the conventional narrative, I will build on that example and further elaborate theory concerned with the availability of social support. To do so, I first extend the general framework by adding the level of analysis as a component. This extension enables me to consider two additional theories here, one concerned with restoration of relational resources held between people in closer relationships and the other concerned with restoration of social resources held collectively in a population. Following the naming conventions applied with SRT and ART, I refer to these two theories as relational restoration theory (RRT) and collective restoration theory (CRT), respectively.

Some of the phenomena addressed by RRT and CRT have already drawn much attention from scholars. I note some of the areas of overlap as I proceed, but in this and other respects more detailed accounts lie outside the scope of this chapter. The accounts I give here nonetheless suffice to identify RRT and CRT as distinct theories and so provide bases for novel research questions and hypotheses not derivable from SRT or ART or from each other. This will help to propel discourse within restorative environments theory, and it can also encourage dialog between restorative environments theory and other bodies of theory. All of this should contribute to a more encompassing narrative about nature experience and health, one that realizes more of the potential of the restoration perspective.

5.4.1 Relational Restoration Theory: Focus on Resources Held Within a Dyad or Small Group

In the account of RRT that follows, I first specify the level of analysis. I then apply the narrative logic used with SRT and ART and treat its respective components in a sequence that represents a process (see Table 5.3).

5.4.1.1 Level of Analysis

In discussing the contents of the general theoretical framework, I have so far only referred to processes on the individual level. However, a theory about the role of the environment in restoration of access to social support cannot be fully articulated only with regard to the person deprived of support; it must also attend to the person or persons who do not provide support and to the circumstances around the failure of the supportive exchange between them. Description of the restorative process must therefore look beyond individuals. RRT focuses on the exchange of instrumental and emotional support in closer relationships, as between civil partners, in a larger family, and among friends, co-workers, and neighbors.

5.4.1.2 Resource

An ability to rely on some close other for some form of support rests on the resources of the person or persons who could provide instrumental and emotional support, including those resources in focus with SRT and ART; however, it cannot be reduced solely to the functional resources that the other person(s) might deploy to provide desired support.

An ability to rely on some close other for support also rests on the arrangements that enable them to exchange support. These often follow from deliberate and extensive measures, such as a choice of a residential location, made with the expectation that diverse forms of supportive exchange will continue over an indefinitely long period and across many situations requiring cooperation and coordination. I refer to these as standing arrangements.

Perhaps most fundamentally, though, an ability to rely on some close other for support rests on aspects of the relationship between them. RRT focuses on interpersonal aspects such as trust; love; respect; common interests; mutual understanding; tolerance of the other’s peculiarities; shared goals, hopes, and mutually reinforced optimism about the future; a shared commitment to another significant person or to an ideal, group, or organization; and a positive valuation of a shared history and of rituals and traditions held within the relationship. Some of these interpersonal aspects, like love and shared goals, may characterize only a few close relationships, while others, like trust and common interest, will also figure to some degree in relationships in the public realm, as between people who frequently meet while walking their dogs in a local park (e.g., Foa, 1971; Henning & Lieberg, 1996; Lofland, 1998).

I refer to these interpersonal aspects of relationships as relational resources; they do not exist in one person alone, independent of the other(s) (cf., Cordelli, 2015; Hartig, Catalano, Ong, & Syme, 2013). As a constituent of any closer relationship, they provide a basis for action by those involved, enabling and motivating the exchange of individual resources, including material as well as personal functional resources. The relational resources also provide a basis for individual and joint action in the completion of their respective personal projects as well as their joint projects and in meeting the role obligations and other demands faced by one or more of them. People commonly establish relational resources progressively, with one, like love, following from the presence of others, such as attraction and trust (cf. Altman, Vinsel, & Brown, 1981). Sustained, reciprocal exchange of support can therefore progressively deepen a pool that comprises multiple relational resources. In a relationship or a set of relationships with a deep pool of relational resources, as in many families and long-established work teams, those involved can hold strong expectations about reliable and sustained provision of that support which the other(s) actually can provide within the available arrangements for exchange.10

5.4.1.3 Antecedent Condition of Resource Depletion

In a given situation, one person may fail to get support from another for reasons related to any of the constituents of the ability to rely on another for support. Stress or fatigue may have undermined the other’s capacity to provide support. Their arrangements for supportive exchange may have weaknesses, perhaps related to problems in movement between the settings and social roles specific to their family, work, and other life domains (cf. Chatterjee et al., 2020; Novaco, Stokols, & Milanesi, 1990). One person may be unwilling to help because some key relational resource has become depleted, as with a loss of trust; a loss of love; recurrent unjustified failures in reciprocity; a loss of mutual commitment; diminished tolerance of the other’s peculiarities; and/or abandonment of shared goals (cf. Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999; Lewicki & Bunker, 1995).

Although the supportive exchange in a given situation might fail for reasons specific to any one of the constituents of the ability to rely on another for support, some people must contend with stable circumstances in which problems with all three of the constituents cascade across situations that recur regularly in their multiple life domains. They struggle to fit restoration pieces into their “life puzzle” as they try to cope with unrelenting and conflicting demands from their own and others’ activities across the settings and social roles of their different life domains. Time pressure, stress, and fatigue become chronic; their emotional well-being suffers; and their relationships get neglected and possibly strained (cf. Schulte, 2014).

When stable circumstances regularly generate situations that wear on the people involved, their relational resources can come to have superordinate significance in their ability to rely on others for support. Those who share a deep pool of relational resources commonly work together to resolve problems related to their standing arrangements for exchange. If possible, they change those arrangements, even when difficult, for example, by moving their residence. If they cannot make better arrangements, they may accommodate the negative consequences as part of their ongoing coping process, even though doing so wears upon them (e.g., Repetti & Wood, 1997; cf. Whitchurch & Constantine, 1993). They may do so with tolerance and sympathy if they know that the problems faced reflect on stable circumstances beyond the control of the person or persons in question (e.g., systemic racism; socioeconomic disadvantage).

RRT thus recognizes that people develop, deploy, and deplete their individual and relational resources in a complex set of arrangements and stable circumstances that have interpersonal, spatio-physical, temporal, and social aspects. In this, RRT has particular concern for depleted relational resources, assuming they have superordinate significance for an ability to rely on some close other(s) for support across situations that arise within the arrangements made for supportive exchange. Looking to the possibility for restoration, RRT assumes that the pool of relational resources has become depleted but not emptied. Relations between those involved have become weakened or strained; they want to bolster them and ease the strain; and they can take action toward that end, including changing their arrangements for exchange.11

5.4.1.4 Features of Transactions with the Environment That Serve Restoration

RRT recognizes that much as the stress and mental fatigue of the individuals involved can play a role in depleting relational resources, so can restorative person–environment transactions like those described in SRT and ART also play a role in relational restoration. Conversely, it recognizes that much as weakened or strained relations can exacerbate stress and mental fatigue, so can transactions between people that ease strain in their relations also play a role in their respective personal restorative processes. Accordingly, RRT complements the individual-level theories about restorative environments by situating restorative person–environment transactions within the ongoing supportive exchange between the people involved.

To do this, RRT first explains how arrangements for supportive exchange can work across situations to shape what happens within a specific situation in which restoration might occur. In outlining that explanation here, I will focus on standing arrangements, although the account also bears on ad hoc supportive exchange. Ideally, standing arrangements help those involved to reduce or prevent needs for restoration; they sensitively accommodate the functional resource limitations of each person involved, their unavoidable personal needs for restoration, and their shared desire to care for their relationship(s) (cf. Clark, 2001). Insofar as their standing arrangements anticipate and provide for their various restoration needs, many of the situations in which restoration occurs will have a routine character; they will occur in particular settings at particular times, as with workday lunches and family dinners, and with particular movements between settings, as with travel home after work, before re-engaging with family responsibilities. When relations between those involved become weakened or strained, one can therefore look to the standing arrangements to see how the routines can be changed to more successfully reduce or prevent personal depletion, provide for personal restoration, and/or support care for relationship(s).

RRT attends to the integral aspects of standing arrangements that bear on how well personal restoration and care for relationships can succeed across situations. One of these integral aspects involves the regulation of social interaction by which an individual, dyad, or small group opens or closes to others (i.e., privacy regulation; Altman, 1975). This process runs continuously, within and across domains, with each person wanting solitude on some occasions and company on others. Within a given domain, the standing arrangements will to varying degrees allow those involved to permit and promote each other’s movement into the different settings that are available, alone on some occasions and together on others. Both kinds of movement can bring personal restoration and care for relationships into congruence. Yet, each of those involved may also well know that the satisfaction of personal needs for restoration will in some situations call for togetherness, as when one would not feel safe going alone for a preferred activity in a preferred setting (cf. Staats & Hartig, 2004), and/or when all know that they would enjoy the activity and setting far more with the other(s) present (cf. Caprariello & Reis, 2013; Staats et al., 2016). By enabling any one of them to spend time alone and by offering means to enhance that person’s experience while away, or by enabling time together and enhancing each other’s experience in that situation, those involved in the standing arrangements can bring satisfaction of their personal restoration needs and care for their relationships into congruence. Conversely, in the way each person gets time alone versus together across situations, satisfaction of personal and relational needs can come into conflict. The manner in which standing arrangements serve privacy regulation thus bears on their success in satisfying needs for personal restoration and care for relationships within the given domain.12

Reciprocity is a second integral aspect of standing arrangements that bears on the success or failure of personal restoration and care for relationships across situations. Standing arrangements rest on reciprocity; those involved will assume some responsibility to provide support just as they form expectations about receiving support (Gouldner, 1960). As indicated earlier, standing arrangements also assume that those involved will develop some sensitivity and responsiveness to the restoration needs of the other(s), so that over time they come to know about each other’s ability or inability to provide support in particular situations. Accordingly, those involved presumably evaluate reciprocity looking to how it holds across multiple situations across time, and not only with a view to immediately successive situations across which one might give and then hope to receive support. Any of those involved could tolerate a failure of reciprocity in a specific situation when it stems from some justifiable inability to provide support (cf. Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999). Insofar as those involved meet reasonable expectations of reciprocity to the extent possible across situations, they can maintain and deepen the pool of relational resources. In contrast, routine unjustifiable failures to reciprocate support will erode the trust, mutual regard, and other relational resources on which those involved have predicated their supportive exchange, making their standing arrangements unstable (cf. Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999; Gouldner, 1960). A persistent lack of reciprocity may prove particularly potent in straining their relationship(s) insofar as it also exacerbates the need for restoration of one or more of the others involved, increasing the burden on the other(s) while also denying them anticipated opportunities for restoration or degrading their restorative quality (cf. Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999; Siegrist, 1996). Conversely, reciprocation of support that involves occasionally forgoing one’s own needed restoration to enable that of another in greater need may well deepen the pool of relational resources within the given domain.13

A third integral aspect of standing arrangements to mention here involves interdependencies between experiences in different situations. Those interdependencies include far more than a link between some acute need for restoration that arises in one situation and then satisfaction of that need in an immediately following situation, as commonly represented in experimental tests of the restorative effects of different environments (Hartig, 2011). They also involve the dependence of the experience of the present situation on what happened in situations that lie farther back in the past as well as on what will happen in situations in the immediate and perhaps more distant future. Those interdependencies inhere to individual and shared memories of past situations, good or ill, and they inhere to individual and shared anticipation of situations to come, good or ill. They figure in the assessment of reciprocity, with regard to support one has provided and received in the past and support that one expects to give or receive in the future; however, the memories and anticipation that constitute experiential interdependencies between situations need not only concern matters of reciprocity. Memories may, for example, concern what those involved have done previously to create relational resources in a situation that resembles the present one, as with recall of a shared milestone event in a particular setting. Memories may also concern experiences through which a setting has acquired particular value for its service in personal restoration and care for relationships over repeated situations, as with the home, a favorite pub, or a local park (cf. Cooper Marcus, 1992; Knez, 2014). The expectations grounded in those memories may concern the availability of similar experiences in that setting in the future, as with the use of favorite places for emotion and self-regulation (cf. Korpela, 1989; Korpela et al., 2018; Korpela & Hartig, 1996). These diverse interdependencies can color the experiences that a person, dyad, or small group has across situations encompassed by their standing arrangements in the given domain. Even when seemingly alone in some setting, a person may through their memories and anticipation remain engaged with other people, activities, and settings in ways that enhance or degrade the restorative quality of their experience.

Together, as integral aspects of standing arrangements that reach across situations, privacy regulation, reciprocation, and experiential interdependencies can powerfully shape the personal and relational outcomes that those involved will realize in a specific situation in which restoration might occur. RRT calls attention to the way that many of the situations in which restoration occurs fit within standing arrangements; it recognizes that those situations occur with some regularity, within a pattern that combines particular times, settings, and people who can refer to past and coming situations in ways that influence their present experience. And, of course, RRT recognizes that, across situations, those standing arrangements attend not only to the personal needs of those involved but also to care for relationship(s), including the renewal of relational resources when necessary. RRT thus complements the accounts of restorative individual–environment transactions given by theories like SRT and ART by setting the situations in which they occur into the stream of situations encompassed by standing arrangements.

RRT also complements the individual-level accounts of restorative person–environment transactions by looking at the transactions between people within a specific situation entered for restoration. It acknowledges that people often do not go alone to natural and other settings for restoration. Accordingly, it considers how the transactions between them can shape the transactions they have with the environment, and, at the same time, how the transactions they have with the environment can shape the transactions between them.

In this respect, RRT builds on a line of studies initiated by Henk Staats. He noted that, like the search for restoration, being in the company of one’s family and friends has long stood out as an important motive for recreational visits to natural areas (e.g., Driver, 1976; Knopf, 1987). To test the joint influence of these two motives, we had participants in an experiment judge the likelihood of restoration with a walk outdoors in a forest of city center (shown in photographic slides), either when alone or with a close friend, and when either mentally fatigued or fresh and alert (as described with scenarios; Staats & Hartig, 2004). Note that although the experiment focused on a specific recreation situation, it assumed the participants’ judgments of the likelihood of restoration in the given environment/company condition would reflect their prior experience with the selection of environments for meeting their needs for restoration. In general, the participants indicated they would appreciate having the company of a friend in either of the settings. Of particular interest here, though, are the results we obtained with the ratings of perceived safety also collected for the four environment × company conditions. We found that greater safety mediated a positive effect of company on the likelihood of restoration, but only for the forest walk. The results also suggested that if safety were guaranteed in the forest, the participants saw a greater likelihood of restoration if alone. These results supported discussion of in situ transactions between two people in terms of what permits and promotes restoration: company may enable restoration in a setting, as by ensuring safety, and it may also enhance or degrade restoration in various ways (see also Johansson, Hartig, & Staats, 2011; Staats, 2012; Staats et al., 2016; Staats, van Gemerden, & Hartig, 2010).

I will not try here to give a systematic account of the different ways in which having company can combine with features of the environment to enable and enhance restorative experience, or conversely deny or degrade it. It will suffice to point out that the concern for the influence of company distinguishes RRT from the theories of the conventional narrative. SRT and ART focus on an individual’s transactions with the environment. Those theories do not address transactions among people or their joint transactions with the environment as focal concerns. Yet, person–person transactions and their interplay with person–environment transactions in a given situation may be an important source of individual benefits as well as shared relational benefits. For example, studies of shared attention and shared experience suggest that when two people in a close relationship can enjoy a positively valenced stimulus together (say, eating chocolate or viewing pleasant images), it amplifies the intensity of the pleasure each receives, even in the absence of communication about it (e.g., Boothby, Clark, & Bargh, 2014; Boothby, Smith, Clark, & Bargh, 2017; see also Shteynberg, 2015).

How does this all bear on understanding restoration in nature within a specific situation? Consider a couple walking in an unfamiliar forest on an early summer day. Their experience reflects on interdependencies across many situations that have occurred within their standing arrangements for supportive exchange. For example, their walk there fits within a history of shared recreational activity, and they have memories of many earlier forest walks. They are visiting the specific forest because they both have long wanted to see a particular species of orchid that they have heard blooms in abundance there at that time. They have also heard that the terrain is difficult, but they trust in each other’s abilities and know they will be able to manage when they go together. Focus now on the transactions between them and the forest that further permit the restoration they need. They have gotten away from heavy demands at work, and this opens for restoration of their personal resources, as described in SRT and ART. Each thus has more capacity to attend to the other than they would have otherwise. The distance from their paid work demands has additional significance in that those demands have weakened their relationship by preventing needed discussion of some important matters; they need to talk over the possibilities and make some plans. An absence of other people and social strictures in the forest makes it easier to open for their intimate sharing, self-disclosure, and emotional expression. With their energetic and cognitive resources freed up, social constraints relaxed and communication open, they are better able to listen to and understand each other’s attempts to make sense of and otherwise reflect on their shared circumstances. Given that relational restoration gets permitted in these various ways, consider how the transactions the two have with each other and with the forest might also work to promote their restoration. They enjoy the sight and sounds of the birds, the smell of moss and leaves on the forest floor, and finally the discovery of the orchid they had so long wanted to see in the wild. Their ongoing engagement with the forest setting sustains restoration as described in SRT and ART, but their sharing of the experience intensifies their engagement; they enhance each other’s experience through expressing their curiosity during the search for the orchid and their delight when they finally can see it together. They renew and reinforce their relationship, resolving undiscussed matters, reaffirming trust in one another, creating some new positive memories, and perhaps seeing new ways to appreciate each other or seeing again sides of each other that they had appreciated before.

This scenario is of course just one out of many that could be used to illustrate how individual and relational restoration processes are intertwined, both through standing arrangements for supportive exchange that run across situations and through the transactions that take place between people while in a specific situation and between those people and the given setting. Speculative and uniformly positive in tone, the scenario is nonetheless plausible; it accords not only with anecdote (Pascal, 2016) but also with findings from different kinds of empirical studies.

5.4.1.5 Outcomes That Reflect on Restoration of Relational Resources

Literature in diverse areas can inform understanding of relational restoration, how it may be intertwined with the restoration of personal functional resources, and how that can occur in natural and other settings. I have already indicated that research has long affirmed that restoration and being together with close others are persistent and important motives for outdoor recreation (e.g., Home et al., 2012; Knopf, 1987), and that people often have company in their outdoor recreation (e.g., Knopf, 1983). Korpela and Staats (2020) reviewed numerous studies speaking to values of solitude versus company while in natural areas, and they relate findings to restorative experience and privacy regulation. Various studies have also shown that movement into a natural setting for recreation can serve family cohesiveness, as through the sharing of pleasant activities and enhanced communication (e.g., Ashbullby, Pahl, Webley, & White, 2013; West, 1986; West & Merriam, 1970). Similar observations have guided practical applications in nature-based therapies for couples (e.g., Burns, 2000) and outdoor program activities that promote the development of relational resources held by parents and children (Davidson & Ewert, 2012). Literature on wilderness programs indicates how they can serve the development of communication and cooperation within groups (Ewert & McAvoy, 2000), and how the experiences they provide can be designed to enlist personal restorative processes in the development of desired social outcomes (Ewert, Overholt, Voight, & Wang, 2011). Holland, Powell, Thomsen, and Monz (2018) reviewed 235 studies of the outcomes of wildland recreation activities such as canoeing, camping, hiking, and backpacking. They found that large proportions of the studies reported on positive mental restoration outcomes and positive pro-social outcomes like increased family cohesion. Epidemiological studies suggest that a pathway from urban residential green space to mental health goes through the perceived restorative quality of the green space and then neighborhood social cohesion, in serial; treating them as independent mediators obscures the way in which they can work together to promote mental health (Dzhambov et al., 2018; Dzhambov, Browning, Markevych, Hartig, & Lercher, 2020; cf. Kuo et al., 1998).

Yet, research has yet to address the assumptions and claims of RRT as such. In general terms, studies inspired and guided by RRT as a theory about restorative environments can focus on the roles that specific physical and social setting characteristics play in relational restoration, as reflected in change in the pool of relational resources or in a particular relational resource. Much as with research informed by SRT and ART, studies can approach such effects as the proximal outcomes of experience in a specific situation or as distal outcomes of experiences across repeated situations. However, with research informed by RRT, a focus on proximal outcomes calls for consideration not only of the transactions that each individual has with the environment but also of the transactions between them, as well as their joint transactions with the environment. Research focused on distal outcomes calls additionally for consideration of the characteristics of the standing arrangements in which the repeated situations occur, with regard to the ways in which privacy regulation, reciprocation, memories, and expectations work together (cf. Ratcliffe & Korpela, 2016). The relevant outcomes and mediators—for example, qualities of the environment and qualities of the interpersonal transactions—may be observed on the individual level or on the level of the dyad or group. Use of measures on both levels can support examination of how personal and relational restoration intertwine.

The account of RRT given here indicates numerous more specific directions for research. For example, experiments can examine how the person–environment transactions that support restoration in one or more of those involved also ease strain in their relations. Experimenters might, for example, artificially induce tension between two friends recruited as participants while also inducing stress and mental fatigue in each of them (cf. Yang et al., 2020). The experimenters might also assess how sharing the experience of the setting subsequently available for restoration (say, a lush tropical greenhouse versus a windowless room lacking decoration) amplifies or attenuates the positive or negative changes that occur during the recovery period, as assessed with measures of affect, cognition, and physiology. They might further test the hypothesis that a mutually amplified beneficial change in the natural setting in turn evokes assessments of relationship quality showing greater forgiveness in relation to the artificially induced tension between them.