Abstract

Collaborative working in the criminal justice system is complex. This introductory chapter synthesises some of its challenges and the role of innovation and organisational learning to address these. In so doing, we present the work of the COLAB consortium and its ambitions to apply theories and methods of activity systems to the field of interagency collaborations and social innovation within the criminal justice system. We explore the basic principles of these and supplementary theoretical and methodological perspectives that are treated in greater detail in later chapters of this book. We raise, in particular, issues and challenges faced in including service users’ voice in service development and innovation before exploring the concept of multivoicedness and its application. This leads to a discussion of distributed responsibility for offender rehabilitation to which many stakeholders including academic institutions should be held to account. The chapter ends with a consolidation of where we are in our current understanding of collaboration, innovation, and organisational learning in the criminal justice context and proposes ways forward.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Preparing people for life after prison, resettlement and a life free from crime is a crucial and complex task. Offender rehabilitation is a key strategy employed by prison services internationally to support this. Programmes of education, employment, health care and other interventions are typically introduced to aid offenders’ rehabilitation, their reintegration into society and reduce the likelihood of recidivism (UK Ministry of Justice, 2013; Skardhamar & Telle, 2012; Armstrong, 2012). These interventions involve an overlap of the work activity of a variety of actors representing professions from welfare (health and social care) and criminal justice services. Good collaboration between these actors, including the prisoner, is required to navigate and better integrate the different interventions and service systems. These latter systems are in an ongoing process of change, struggling to meet effectively the needs of the individual, organisation and the society. Interagency work and collaboration are necessary in this context for continuous learning and innovation creation to take place that address these challenges.

The criminal justice system is a complex environment with many interacting and unpredictable factors. This creates multifaceted challenges for the work activity of the actors involved in prison services and health/welfare services. The complexity of collaborative working in this context can be defined as a “wicked problem” (Rittel & Webber, 1973; Hean et al., 2020). This means the exact problem is often difficult to define; it exists within open systems being influenced by a multitude of interacting influences; professionals may individually be able to come up with multiple solutions dependent on their own experiences but these are each difficult to predict, test or disprove and will vary in effectiveness depending on the context and stakeholders involved. As such, any solution aimed at improving reoffending rates and rehabilitation through optimising interagency collaboration, learning and innovation will often not be consistent with standardised care pathways that promote uniform, one-size-fits-all coordination of care across agencies (Hean et al., 2020).

This book aims to explore some of these wicked problems and challenges to collaboration the prison and penal systems are currently facing and the role of innovation and organisational learning to meeting these challenges. The concepts of interagency collaboration, organisational learning, co-creation and innovation are positioned within a wider debate of prison as a means of welfare versus punishment. The book also discusses the active role of researchers in organisational change, service development and innovation. In this it considers issues of inclusion when it comes to representing the service professional and service user voice in the innovation process. The book hereby provides a resource through which academics, advanced graduate students and professionals/prison administrators interested in prison/criminal research and service development can explore key issues and methods in enhancing collaboration, organisational learning and innovation in this context. The book takes a European focus that the reader may wish to compare and contrast with other international contexts such as North America and Australasia.

There are two sections to the book. The first section presents some of the current collaborative practices and challenges to these in a series of case study criminal justice-related environments. Imprisonment presents an opportunity for the individual to prepare for a life free of crime, and careful coordination of different services, to prepare and support people for release, is often required. This book section has a wider scope than addressing collaboration within the prison alone but covers collaborative practice at several points in an individual’s trajectory through a criminal justice system and the roles of a variety of stakeholders including the third sector, state and academic stakeholders within this.

The second section of this book explores strategies and methods available to researchers that can promote collaboration, management and innovation. Action-based participatory research or interventionist approaches to promote innovation and collaboration are introduced as is the role of researchers in these processes. The section examines how researchers can be proactive as agents of organisational change that are often needed to tackle some of the challenges addressed in the first section of this book. Further, risk management strategies to increase quality of integrated care are explored as potential methods and tools for interagency boundary crossing. Means of including multiple voices in service development and innovation are also examined, as is the potential transferability of methods and interventions used in other criminal justice contexts, to successfully promote innovation and organisational learning. This section also provides a resource to promote positive relationships between key actors involved in improving the prisons and penal systems for all involved.

The COLAB Consortium

The content of the book is based on efforts of the COLAB research consortium and its members. COLAB (Horizon 2020 funded CO-LAB MSCA-RISE project number 734536) is a partnership of European researchers and practice professionals comprising 7 Universities and 3 practice organisations related to the criminal justice system from Norway, Finland, UK, the Netherlands, Denmark and Switzerland. The COLAB consortium is a unique community of practice (Wenger, 1998) aimed at building international research capacity and cooperation between a range of complementary disciplines. It is operationalised through a series of inter-sector and international secondments or exchanges between academic and practice partners with the common aim of improving offender rehabilitation and resettlement. The aim of the consortium is to build more effective models of collaboration between health or welfare services and criminal justice services. The longer term intention is to have an impact on the health, welfare and well-being of the prisoner population, whilst securing public safety and reducing reoffending rates. The secondment structure of the project enabled close cooperation between academic and practice partners to develop. This is shown by most of the chapters in the book that have been co-written by a combination of practice and professional partners from COLAB, taking a community of practice stance and learning by working together on this common dissemination goal. The secondment structure also favoured an ethnographic research-informed approach to research with researchers being able to immerse themselves over a period of time in various crimnal justice contexts.

The membership and structure of the COLAB project has meant that the Norwegian prison system has received particular attention here. With the lowest recidivism rates internationally (Fazel & Wolf, 2015; Graunbøl et al., 2010) and noted for their culture of rehabilitation within their prison systems (Pratt, 2008), the Norwegian system provides an interesting backdrop for many of the chapters included. The researchers and authors of the chapters are from a more varied European background, however, and, with the exception of Sepännen and co-authors (Chapter 9), represent a group of international researchers examining the criminal justice system in a national context other than their own. For example, Rocha and Hean (Chapter 6) are a Brazilian and South African, respectively, making sense of a UK liaison and diversion service and Murphy and colleagues (Chapter 4) are Danish researchers making sense of the Norwegian prison sector. This cross-national research enriches our understanding of collaboration in these systems by applying the eye of the external researcher which makes the implicit characteristics of each national context more evident. However, this has limitations also associated with language issues and COLAB members not being familiar with the national context they are exploring.

Cultural-Historical Activity Theory and Change Laboratory Model as a Guiding Framework

As to research-based methods, COLAB, in its inception, drew from an interventionist line underpinned by Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) (see e.g. Engeström & Sannino, 2011; Engeström, 2001, 2015; Virkkunen & Newnham, 2013). It made a particular case for implementation of the Change Laboratory Model (CLM) of interagency working and workforce transformation as a potentially more effective means of supporting interagency collaborative practice in this context than current interagency practices. CHAT and the CLM both found favour within the COLAB work because researchers working on the project had previously used these extensively to analyse and facilitate change in collaborations within and between organisations in other fields. However, none of the COLAB project members had applied these in studying collaborations between prison services and mental health services. These have since been proposed as useful tools to provide a holistic understanding of the complex, multifactorial context of collaboration in the field of criminal justice (see Hean et al., 2018). Drawing also on the complementary expertise in the consortium in other models of collaboration, organisational learning and innovation, the consortium had as a primary objective the exploration of the suitability of CHAT and the CLM model, and its adaptation, to the welfare/criminal justice context. The complementary expertise of the consortium is reflected in the content of this book.

In brief, CHAT is rooted in the legacy of Vygotsky, Leont’ev and Luria and it is a multidisciplinary theory, which has gained increasing popularity and relevance amongst researchers in the field of organisation studies (Adler, 2005; Blackler, 2009). CHAT offers a system-level view for researchers and practitioners to analyse work, learning, development and change processes. It provides conceptual and analytical tools, such as the models of activity systems and the methodological cycle of expansive learning. CHAT includes an interventionist methodology, named the Change Laboratory, for enhancing reflection of struggles, competing interests and contradictions in collective activities. Participants in a Change Laboratory are encouraged to reinterpret and discuss their work using video-recordings as a “mirror” reflecting back to them their work place activities. Based on ethnographic data, Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3) and Kloetzer et al. (Chapter 7) provide examples of these mirror materials. Also, a variety of analytical tools are used to analyse and transform work practices, such as the activity system model, the notion of contradiction and the cycle of expansive learning actions. The role of the researcher is to introduce these tools and to facilitate this process. Sepännen and colleagues (Chapter 9) show us how this learning can be facilitated at several points during a service development intervention including both in the design phase of the innovation process but also during the evaluation of the intervention’s outcomes. In these interventions, the end results of learning and change are not predetermined by the interventionist, and the outcomes are designed by the participants as they work out expansive solutions to the contradictions in their activity systems (Virkkunen & Newnham, 2013).

CHAT as a conceptual framework is applied in this book by Rocha and Hean (Chapter 6) to explore the historical development in work activity within Liaison and Diversion Services in the UK. Further, Dugdale and Hean (Chapter 5), Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3) and Lahtinen and colleagues (Chapter 2) take a CHAT perspective as a means of articulating the collaborative work activities taking place between prison staff and prisoners in Norway. Hean and colleagues (Chapter 8) refer to CHAT as a means through which professionals participating in researcher-facilitated interventions can identify contradictions and use this analysis to make sense of and transform their work activities.

Other Theoretical Lenses and Integration Models

The international and interdisciplinary nature of COLAB members and authors of this book ensures the usage of a breadth of theories other than CHAT in many of the chapters of this book. Murphy and co-authors (Chapter 4) for example by using neo-institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991) and sense-making theory (Weick, 1995) show how actors in a Norwegian low-security prison “live with” multiple and potentially conflicting institutional logics.

Many of the chapters of this book refer to service integration models, which can be defined as those methods of funding, administration, organisation, service delivery and care designed to enhance collaboration within and between different services (Kodner & Spreeuwenberg, 2002). Integration models vary in their characteristics and are positioned along a continuum from full integration to full separation of services. The optimal position of one service related to another is usually defined by the organisational context and the needs of the service users (Ahgren & Axelsson, 2005; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). Different countries will have diverse ways and models in which health and social care (and especially the mental health services) are integrated with criminal justice (and especially prison) services. These can be located “in the intersection” of different institutional logics of rehabilitation versus control, of punishment versus care.

In this book, because of the predominance of Norwegian prison research in its focus, the Norwegian import model of service integration is the most commonly discussed model of integration, i.e. a model of integration where external public welfare agencies of health, school, library and clerical services deliver their services for people in prison in the same way as they do for other citizens. The following chapters discuss this integration model in relation to how it impacts collaborative practices within prisons and between prisons and external services, see Dugdale and Hean (Chapter 5), Murphy et al. (Chapter 4), Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3), Lahtinen et al. (Chapter 2). These chapters show how the services vary in where, along the integration continua, each prison and its surrounding services lie and explore how collaboration takes place in these different contexts and levels of integration. Dugdale and Hean (Chapter 5) show how the import model of care provision falls away in a transitional prison/half-way house. Contact and collaboration between prison and external professions are low or non-existent and mediated through the prisoner themselves as they, the prisoner, must actively seek out external service professionals themselves on the outside. Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3), in their description of a low-security prison in Norway, uncover similar challenges in inter-organisational interactions between specialised mental health services and local prison services. When interagency collaboration between prisons and other services is weak, this makes it difficult for prisoners to navigate between the different services before and after release. Supporting this navigation task can then fall to members of the voluntary sector (see Kloetzer & colleagues, Chapter 7), and processes typically rely on informal procedures, goodwill, imagination, determination and the skills of dedicated individuals.

From an activity-theoretical perspective, the meeting and potential tensions between different institutional logics can be seen as drivers for collective learning and change. In this, the models and practices of integration are crucial as these impact the way institutional logics can eventually coexist. Lahtinen and colleagues (see Chapter 2) provide examples of where the distinct institutional logics of control versus care meet during the conduct of interagency meetings and how these are then resolved.

Similarly, Murphy and Seppänen and colleagues (Chapters 7 and 9, respectively) unravel how institutional logics can exist in parallel and develop a balance that can be described as “dynamic security”. From the Finnish context, treatment and control are not seen as separate ends of a philosophical continuum but as preconditions for effective rehabilitation. In an open prison in Norway, Murphy and colleagues find that the prison and health care professionals have developed a range of ways of making sense of their common world, including the use of narratives and metaphors.

Fluttert and colleagues (Chapter 11) analyse collaboration using the concept of “Self” and explore awareness of one’s own perceptions as a concept to underpin the communication that occurs between a range of actors. These authors are particularly interested in the awareness of self and dialogue with others in therapeutic situations. They recognise that awareness of self is impacted by, and reacts to, the voices of others. The awareness of self in relation to others is also picked up by Ødegård and Bjorkley (Chapter 10) for whom dialogue is described as a recognition of multiple perspectives and “a move from a perception of reality as absolute to one that is individually and differentially perceived”.

Methods for Promoting Social Innovation and Systemic Change

Systems-level integration and individual-level collaborations are not only important for the everyday delivery of correctional and health services but are key to the social innovation process, a process of co-creation between multiple actors that allows for a cross-fertilisation of interprofessional knowledge. In this book, social innovation is perceived as both the process and outcome of taking new knowledge or combining existing knowledge in new ways or applying it to new contexts. It is primarily about creating positive social change, and improving social relations and collaborations to address a social demand (European Commission, 2013; Hean et al., 2015). Furthermore, innovation is essential in the prison environment where prison population demographics and challenges are in a constant state of flux.

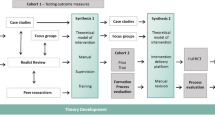

An innovation process involves participants engaging in expansive organisational learning (Engeström, 1987/2015), an iterative and cyclical process through which individuals collectively define and redefine their activity. In Chapter 8, Hean and colleagues outline an innovation processes aiming at promoting organisational learning, collaboration and innovation between multiple professionals from participating organisations. The cycles involve participants identifying tensions and contradictions in their work activity, analysing and making sense of these through multiple perspectives, modelling/creating new solutions to these, and locally implementing and experimenting with new forms of activity. Participants, throughout the process, reflect on the outcomes of the intervention and any new tensions that have arisen through this experimentation process before consolidating or upscaling organisational transformations.

Some chapters illustrate how innovation, and the expansive learning processes that underpin these, may develop organically in the prison setting without the interference of the research community. In Rocha and Hean (Chapter 6), practice professionals and policy makers identified the need for a more standardised offering of care provision in Liaison and Diversion services in England and Wales. Taking a historical perspective, the authors describe the expansive learning process that took place, showing how contradictions were identified and solutions to these developed and tested in practice. The chapter by Lahtinen and colleagues (Chapter 2), describes how leaders from different services, when participating in regular interagency meetings in a prison, responded to a lack of prison officer and prisoner voice at these events. They do so by examining during their leadership meetings the use of a mapping tool (BRIK) completed by prison officers with the prisoner. This tool they believed would capture and represent the voice of the prisoner during their leadership meetings. The chapter highlights the tensions that arose in the leaders’ examination, experimentation and evaluation of this, their innovative use of BRIK. The tensions included issues of confidentiality of cross-agency information sharing.

Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3) demonstrate how a prisoner, in his interactions with a service, may also be part of such a cycle of collective learning. They refer to the prisoners’ own transformative agency, a concept Sannino et al. (2016, p. 4) describe as “a quality of expansive learning” that “requires breaking away from the given frame of action and taking the initiative to transform it”. As the prisoner is involved in their own personal transformation, so too can they be engaged in system-level change and learning.

The Service User’s Voice

The inclusion of the service user voice in the innovation and learning process is the central theme of this book, and it is explored in terms of their engagement in change and learning efforts (Hean et al., Chapter 8; Nielsen & Kajamaa, Chapter 3). Ideally, for their voice to be heard accurately, prisoners should actively participate in person in service development efforts. If this is to happen, however, those facilitating such activity should be aware of the need to build mutual trust between prisoners and between prisoners and staff participating in these events. They should recognise and compensate for power asymmetries that may exist between participants (see Hean et al., Chapter 8). Specific skills are needed both in the intervention participants and the facilitator to make constructive dialogue possible in the highly hierarchical prison setting.

Lahtinen and colleagues (Chapter 2) describe how tools, such as BRIK, completed by prisoners and prison officers, brings their voice into leadership interagency meetings even though they do not appear in these meetings in person. Further, the HCR20 and ERM tools (see Ødegård & Bjørkly, Chapter 10 and Flutter et al., Chapter 11), by acting as boundary-crossing tools, can be used to capture the voices of prisoner and other professionals’ voices and bring these into the care process. Parker et al. (Chapter 12), and Turner Wilson and colleagues (Chapter 13) explore the value of emic, etic and etemic perspectives. They draw a distinction between the voice of the prisoner as service user (emic) versus the voice of the professional (etic) on what services should look like. Although, including the voice of the prisoner in service development is challenging (Hean et al., Chapter 8), if excluded, it perpetuates the etic perspective alone. Parker et al. call for an etemic view, where both the emic and etic views, each with their own strengths, are combined (Heaslip et al., 2016; Parker et al., Chapter 12). Wilson Turner and colleagues (Chapter 13) provide an illustration of this etemic perspective in presenting a case of a collaboration between a worker and an ex-prisoner. One of these authors, in having multiple identities, acted as a boundary spanner in the COLAB activity and hereby proved to be an invaluable research agent, crossing boundaries of academia, service providers and the service user, simultaneously. Through his etemic perspective he was able to access both professional and service users that the researchers themselves, through cultural differences (national and sector), had previously been denied.

A key issue in including the voice of service users in interventions relate to the vulnerability of the prisoner. Parker and colleagues (Chapter 12) delve more deeply into the concept of vulnerability and reflect, in their discussion of critical ethnography, on how the stigma and labelling of prisoners is problematic. At the level of a discrete intervention, researchers may unconsciously hold biases of prisoners, and for example select certain material representing a particular dimension of the offenders’ experience and not others. This may also be manifested in the slant of their analysis, as Wilson Turner and co-authors (Chapter 13) concur. They recognise how they may have consciously or unconsciously prioritised and edited the material they collected, in their jottings, narratives and choice of photos that informed the narrative in their chapter. The discussions of these chapters raise issues of the epistemic violence possibly embedded in the use of data collected by the researchers or professionals in any analysis and interpretation process from which prisoners are absent (Spivak, 1988). Whether influenced by bias or not, the accuracy with which the voice of the prisoner is actually represented in the tools described in Chapters 6, 10 and 11 remains unexamined, however.

Kloetzer and colleagues (Chapter 7) demonstrate how the perspective of the researcher and the professional may be very distinct from each other and from that of the prisoner. Issues relating to the meeting of contrasting perspectives are also observed in Sæbjornesen et al. (Chapter 15) where the implications of contrasting mentor and ex-prisoner perspectives on the rehabilitation prospects of offenders are compared and contrasted. In other words, any research report or intervention is dependent on what the researcher may or may not see as worthy of reporting. Similarly, at a systems level, research ethics committees can be strict in their control over studies that propose to talk directly to offenders. The committee limitations placed on the researcher when they design their studies can discourage researchers from talking to prisoners at all. Although the intention of the committee is to protect the prisoner, and minimise their vulnerability, this also serves to silence the voice of the prisoner (Seppänen et al., Chapter 9). This suggests that, if prisoners are not directly engaged in service development, professionals/researchers may not be in a position to represent the view of the prisoner.

Organisational Multivoicedness

The prisoners’ voice is not the only perspective that is in danger of being silenced in research and innovation in the criminal justice environment. Ødegård and Willumsen (Chapter 17) present clear instances where researchers have prejudged the needs and problems of practice institutions. This chapter emphasises the need for approaches to innovation and service development in which problem identification and solutions are created from the bottom up, and a balance is found in the input between the direct and indirect engagement of employees, service users, researchers and policy makers (see Rocha & Hean, Chapter 6 for a discussion of the dangers of top down implementation of policy). This is clearly observed in Kloetzer and colleagues (Chapter 7) when interview data are analysed by first the researcher and then contrasted with the analysis made by staff members from the host organisation themselves participating in the research. Both analyses have utility but their distinctiveness needs to be acknowledged as does, at the end of the day, the priority that must be given, in service development interventions, to what practice see as being the problems at hand and not what the researchers decide the problems to address should be.

Methods of organisational change, innovation and collaboration can involve the unification and comparison of multiple and sometimes contrasting perspectives of participants and facilitators. Theoretically, this process is informed by the concept of multivoicedness utilised in activity theoretical studies, and forming one of the key principles of the Change Laboratory method (Virkkunen & Newnham, 2013; Kerosuo & Engeström, 2003). Multivoicedness is anchored in the theoretical tradition of dialogism (Bakhtin, 1981, 1984, 1986; Markova, 2016) that postulates that the Self and Others are interrelated on ontological, epistemological and ethical levels. The Other is not in opposition to Self, but part of Self (Aveling et al., 2015). From this perspective, collective activity is mediated by the internal and external dialogues in which people participate (with actual or inner voices) representing the diverse communities from which participants are drawn. This relates to Bakhtin’s concept of polyphony, a multivoiced reality, “a plurality of independent and unmerged voices and consciousnesses…” (Bakhtin, 1984). Here each utterance made by any one individual in any interaction is anchored in a specific speech context and also beyond to connect to distant others. For Bakhtin, the role of the person being addressed (addressee) during a dialogue between actors is critical. Each utterance is addressed to a postulated addressee, who is present in the mind of the speaker/writer, and whose “active and responsive understanding” is anticipated. Our words are always “half someone else’s” (Bakhtin, 1981) and the sense we make of our world is created intersubjectively or collectively by people both present and absent

The concept of multivoicedness is useful not only in workplace interventions involving groups (see Hean et al., Chapter 8), but also in the one-to-one therapeutic situations that Fluttert and colleagues (Chapter 11) describe. In their case, the ERM helps prisoners reflect on the dialogue between self and the voice of internal and external others as a means of managing their risk of violent behaviour within the prison. The prisoner’s voice and that of the differing professionals supporting them inter-penetrate.

Whether at the therapeutic or systems level, establishing a dialogue between the actors participating in the learning process is necessary for collective sense-making, shared understanding and learning. Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3) spell out, however that the expansive learning cycles, and the transformative agency these cycles engender, do not always occur spontaneously and can become blocked. This is illustrated in the poor interactions between external mental health services and prison health staff, in a small Norwegian prison. When the collaborative process is not made explicit and only understood tacitly, then innovations are serendipitous and left to chance rather than a culture of innovation being developed within the criminal justice environment. Explicit methods of innovation promotion are thus required. There is a place for researchers then to take an active role in providing such methods that can facilitate organisational change, service development and innovation. This opens up a discussion about responsibility and accountability more widely in any collaboration and in the innovation process in particular.

Who Has Responsibility for Rehabilitation?

A key dimension of interagency collaboration in service provision is the allocation of roles and responsibilities (Hean et al., 2017). A typical question then is which service provider has the responsibility to support the needs of the prisoner and their rehabilitation? The distribution of responsibility depends on context and is likely to be distributed across multiple actors (Miller, 2001; Hean et al., 2017). Although control of the prisoner clearly lies with the penal system, especially prisons and probation services, who then has responsibility for their rehabilitation?

Prisoners themselves of course have the responsibility to address their own needs and to a certain extent, direct their own lives, but their capacity to do so may be impaired. Professionals working in prison and health/welfare services also have responsibilities allocated based on their capacity/training to support a particular need. This means responsibility is distributed according to the competence of the professionals involved. However, a professional may have the capacity in terms of training but workload and emotional aspects related to this may make offering adequate support impossible (Miller, 2001; Hean et al., 2017). This is illustrated by Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3) in their reference to the LEON principle (lowest efficient care level) whereby responsibility for treating a prisoner with mental health issues is directed to primary health care providers in the prison in the first instance rather than the less cost-efficient specialised services. Finding a balance between cost and capacity is difficult to achieve and prison primary health providers feel they have a disproportional responsibility for treating mentally ill prisoners when they do not have the capacity/competence for this task.

Miller (2001) also describes responsibility being distributed by virtue of who knows the individual best and is closest to them (communitarian responsibility). In the case of prisoners, the family member may know them best as may the prison officer who engages with the prisoner on a daily basis. Although their capacity to treat the prisoners’ needs (e.g. a mental health issue) may be less, the prison officers’ proximity to the prisoner suggests they have a responsibility to support them. They will require information from mental health specialists, for example, if they are to take this responsibility, however. Fluttert and colleagues (Chapter 11) discuss how the encouragement of prison officers to engage in the ERM risk assessment may enhance their capacity to support the needs of offenders. Ødegård and Bjørkly (Chapter 10) suggest something similar when exploring how the HCR20 might be used. The question is how prison officers can engage in these joint assessments or access information on the specialised needs of the prisoner more widely bearing in mind the delicacy of information sharing between services. Privacy hinders information sharing between services, and health and prison services struggle with the problem of which knowledge to share, with whom and for which purposes. They need to find a balance between the right to privacy of the prisoner and at the same time improve the holistic management of life, care and treatment.

The perspective on communitarian responsibility may also be broadened to include the role of society in prisoner rehabilitation. In light of the responsibility of the citizen, such as Greta Thunberg in climate change, who and what is the responsibility of the citizen in supporting vulnerable offenders during and after release? Kloetzer et al. (Chapter 7) and Sæbjornesen et al. (Chapters 14 and 15) explore the perspectives and challenges facing volunteers working in a third sector organisation mentoring ex-prisoners. These mentors illustrate an example of average citizens taking responsibility for the rehabilitation process.

Considering the question of allocation of responsibility brings us to reflect on the role and responsibility of university-trained researchers in the offender rehabilitation process. Traditionally, researchers are expected to generate new knowledge and be neutral bystanders. In this book, we take a more active stance, with some fundamental caveats, that researchers have a more active and participatory role and responsibility.

Academic Engagement in Rehabilitation

In their capacity as educating institutions, universities have a responsibility to train health, social care and criminal justice professionals in interprofessional collaboration and innovation competencies, including interagency communication, intercultural competence and what Nielsen and Kajamaa in Chapter 3 refer to as boundary-crossing expertise. Some of these skills are included in national health and social care curricula in many countries but may be bypassed or are referred to only tangentially or theoretically in the training of police and prison officers (Hean et al., 2011; Hean et al., 2014; Hean 2015; Hean et al., 2017). Innovation skills seldom appear. Students from health, social care and criminal justice fields benefit if there are opportunities for them to be exposed to real-life case studies of prisoners, be exposed to prison visits and volunteer in prison and related institutions as part of their professional placements. COLAB had these responsibilities in mind, in its aim to develop resources to promote learning of collaboration and innovation competences. These endeavours are not without their challenges, however, as described in more detail in Ødegård and Willumsen (Chapter 17). They call for training to involve the promotion of a kind of expansive learning process in students, rather than traditional professional training in specified content.

In their capacity as researchers, university staff have a responsibility to describe and hereby potentially disrupt the view of current professional practices. Their analysis can provide an external and alternative lens as an aide to reflection for professionals and other academics, disrupting their current and unexamined views of the collaborative practice status quo and helping them see the familiar as strange (see Hean et al., Chapter 8). This may be a trigger for organisations to take these findings forward to make change and innovation for themselves. Chapters 2–7 and 9 of this book explore some of these potential triggers, exploring collaboration challenges in a variety of Norwegian, Finnish and English criminal justice settings. The chapters focus particularly on the frontline worker perspective of what the challenges are on the ground. These chapters recognise the importance of these workers in terms of their understanding of the local context and their impact on the implementation of policy and organisational change (Lipsky, 2010). It should be noted that with the exception of Kloetzer et al. (Chapter 7) and Sepännen et al. (Chapter 9), that it is generally the researchers’ analysis of these triggers that is being presented in these chapters.

Education institutions also have a responsibility to be facilitators of change and innovation by facilitating organisational learning, collaboration and innovation processes. Researchers can take this active role by being innovators themselves as Ødegård and Willumsen (Chapter 17), for example, describe the COLAB consortium as providing “sites for innovation where new relationships for collaboration, different ways of knowledge production and designing/implementing change to improve services for the benefit of service users are created”. They explore the development and co-creation process between the university and practice professionals of, what was initially envisaged to be a training programme, developed into a web-based resource to respond to practice needs. It aimed to build the boundary-crossing expertise required and explored in Nielsen and Kajamaa (Chapter 3).

Researchers acting as innovators themselves is also illustrated in chapters exploring the development and utility of tools (such as risk assessment tools) as boundary objects. Murphy et al., in Chapter 4 differentiate between uniprofessional, multi-professional or pan-professional tools that are practice tools used to unify the multiple inputs of engaged agencies and promote dialogue between them. The development of these tools often involves the innovative transfer of knowledge from one discipline into another. Lahitinen and colleagues (Chapter 2) show how prison interagency meetings introduce the digital tool BRIK to serve this function. This is also illustrated by Fluttert et al. (Chapter 11) in their exploration of how the ERM tool may be transferred from the forensic psychiatric institutional context, in which it was initially developed, into the prison setting and be used by prisoners and prison officers together to reflect jointly on what triggers a person’s descent into violence. Similarly, Ødegård and Bjørkly in Chapter 10 illustrate the innovation process at work in their novel combination of the HCR20 and PINCOM instruments. They recognise assessment of risk of violence as a substantive area of practice where interprofessional contact between health and prisons, and effective collaboration between the two, is required. The offender may react differently in different contexts and information provided by different professionals on the circumstances that trigger offender violence is invaluable to risk assessment and offender rehabilitation.

A final example of researchers as innovators, and one at the heart, of the COLAB consortium, is the transfer of the Change Laboratory method (CLM) to the new context of the criminal justice system. This also represents a second way in which researchers may take an active role in organisational change by taking responsibility for facilitating the dialogue between stakeholders necessary for innovation. Hean et al. (Chapter 8), describe the theoretical underpinnings of double stimulation and the utility of mirror material as key methods within the Change Laboratory as a means of stimulating meaningful dialogue between actors. Mirror data are representations of practice and work activity that can take the form of extracts from an ethnographic phase of an intervention (e.g. quotes from interviews, videos or photos of observed practices in situ). Participants in a Change Laboratory workshop are encouraged to reinterpret and discuss the mirror material using a variety of cognitive tools, such as a theoretical framework, to make sense of what they see. CHAT is one of these theoretical frameworks. The role of the researcher is to facilitate this process. They present materials to professionals and service users participating in an intervention as a mirror of their everyday work activity. Dialogue comes from them together making sense of this mirror material and identifying where tensions and underlying contradictions in the system lie (Sannino et al., 2016). In Chapter 3, Nielsen and Kajamaa demonstrate how CHAT may be used as a cognitive tool to make sense of the mirror material that could be introduced to a CLM and act as a trigger for expansive learning between participants from different agencies. Kloetzer et al. (Chapter 7) discuss the challenges of bringing mirror material (labelled as micro dramas and dialogical artefacts), that is analysed very differently by researchers and participants, to interventions to stimulate dialogue within a development workshop. Imaginative, evocative and sensitive ways of representing mirror material may be particularly effective and can draw on the anthropological techniques employed by Turner Wilson et al. (Chapter 13) when using jottings and photos to capture their experiences of the third sector in Norway working with prisoners and ex-prisoners. This has particular relevance to any intervention that might use this material as stimuli in a developmental workshop but in such a way that dialogue can occur in a safe space. The importance of this safe space in social innovation is a topic also addressed by Hean et al. (Chapter 8).

Although we take the stance that researchers have a responsibility to actively engage in organisational change and offender rehabilitation, there are two main caveats. The first is the challenges facing setting up academic–practice partnerships. In Chapter 16, Hean and colleagues explore these challenges more broadly using the experience of four COLAB members and the theoretical lens of the contact hypothesis to reflect on these whilst suggesting strategies through which these relations can be enhanced. Ødegård and Willumsen (Chapter 17) using the lens of social innovation and communities of practice, reflect specifically on the academic–practice relationship when building training opportunities. Whilst these two chapters discuss challenges of academic/practice collaborations, Turner Wilson and colleagues (Chapter 13) take a more positive angle reflecting on the valuable anthropological experiences of three English COLAB members (one researcher and two practice professionals) and their experiences of crossing the academic/professional/national divide.

A second caveat to active academic engagement in organisational change is the vulnerabilities of the people involved. We acknowledge the vulnerability of the researcher, when dealing with complex offenders. The tragic events of university colleagues killed during the London Bridge in the UK in 2019 terrorist attack bring this home (McQuillan, 2019). It raises questions as to the capacity of researchers to actively engage in the offender reintegration process, keeping themselves and others safe whilst doing so. The vulnerability of all participating in organisational change must be acknowledged, and special attention should be paid to researchers that are new to the criminal justice context (see e.g. Jewkes, 2012; Sloan & Wright, 2015).

Final Thoughts and Further Research

This book addresses a gap in the literature of understanding collaboration, innovation and organisational learning in criminal justice systems. The chapters show that collaboration between all actors, including offenders, is required to navigate this system effectively. Otherwise work activiites and services become fragmented or compartmentalised. Information sharing is blocked and this leads to knowledge disparities between agencies and reliance on informal and personal interagency relationships. There is often a lack of contact between agencies and there are structural challenges to collaboration at an intra- and especially the interagency level. There are national policies that are aimed to promote integration and hereby collaboration (e.g. national models of rehabilitation, diversion/liaison in England and the Import Model in Norway) but the implementation of these, at the local level, varies. There is limited time, staff and financial resources leading to a depreciation in the value given to holistic work activity. There are tensions caused by a lack of shared meaning between actors when using workplace tools designed to promote collaboration and there is evidence that workplace structures are not keeping up with a change in prisons from a security/control to a rehabilitation focus. As a consequence, professionals may not have confidence, knowledge or competence to support offenders in achieving their goals of life stability, meaning, hope and the feelings of self-worth they need to manage a future without crime. Despite the problems in collaboration, and hereby innovation and organisational learning, we challenge the idea that security and care are on opposite ends of the continuum and show, in the studies included in this book, new innovative ways in which these can coexist.

The authors also explore and reflect upon the wider responsibilities of the research communities to actively engage in organisational change and discuss the potential of methods that promote organisational collaboration, learning and innovation. A culture of collaboration is important, but we understand little still of how this culture can be created within prisons. Without a culture that is pro-collaboration and innovation, it is unlikely that researchers will be invited into prisons to run bottom change efforts. The book contributes to an understanding of the challenges facing interagency collaborative practice in the criminal justice system, capturing the frontline professional and offender perspective in this context, which was previously poorly understood. It is only the tip of the iceberg, however, and we hope the book serves as the starting point for more detailed studies in other European and international settings. COLAB membership has meant that this book has leant towards particular national settings, theories and interventions but this European and Norwegian focus means there is scope to further explore collaborations in other European and international contexts.

As interagency working is found to be particularly problematic, we recommend future research focus particularly on interagency interactions when criminal justice services and external services are fully segregated from each other on the integration spectrum. There is a need for training in methods of collaboration and innovation in the criminal justice staff but training has timing, resource and logistical implications. Further work is required to clarify the relevance of this type of training for frontline professionals working with offenders in crisis and to develop means that suit the busy and complex lives of the professionals involved.

There is further scope still to explore the methodological challenges of researchers working in prison environments and in international, interdisciplinary milieus. Researchers should pay particular attention to building strong, long-term practice–academic relationships based on trust and logistical ease. We recommend that attention be paid by practice and academia to work on developing a perceived and mutual understanding of the need/demand for organisational change. Our findings suggest that researchers are cogent of the biases they hold of the offender population group and must be prepared to manage the biases of key participants. Building on the current discussions of integration tools and models, and the use of metaphors and narratives, researchers should develop further the use of pan-professional and multi-professional tools, utilised as boundary objects and explore further novel ways of capturing the service user’s voice. Researchers should also explore further how boundary spanners, such as one of the authors in Chapter 13, can be better utilised to produce more valid research and useful interventions.

Many of the chapters of this book show that Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) has strong potential in the development of criminal justice settings. Theoretically, CHAT can underpin the sense-making that takes place in these settings, but CHAT is naturally not the only sense-making tool and presents only one specific lens. For further studies we recommend a multi-theoretical approach and there is scope for many other perspectives, e.g. institutional theory and negotiation theory, that could be explored in greater depth. There is now also a need to test methods, such as the Change Laboratory in practice, with the permission of the high-security environments in focus in the chapters of this book.

It must be acknowledged that there are ethical issues to be carefully considered and that there is “emotional labour” involved in studying this context and its processes. The chapters in this book have presented evidence of workplace activity conducted mutually but with flexibility and feelings of autonomy. Professionals from different organisations, work together in a hybrid configuration of actors, with different, potentially competing institutional logics, but have often engaged in learning processes leading to actors being able to oscillate between the institutionalised logic of their own profession and a shared logic centred on the needs of the offender. It is thus also important to note that unequal power relations may occur between the participants of change efforts within these contexts. To conclude, we feel that our understanding of interventions in the criminal justice setting is still in its infancy and we will, with great enthusiasm, continue our research and efforts from here.

References

Adler, P. S. (2005). The evolving object of software development. Organization, 12(3), 401–436.

Ahgren, B., & Axelsson, R. (2005, August 31). Evaluating integrated health care: A model for measurement. International Journal of Integrated Care, 5.

Armstrong, S. (2012). Reducing reoffending: Review of selected countries. SSCJR: Edinburgh.

Aveling, E. L., Gillespie, A., & Cornish, F. (2015). A qualitative method for analysing multivoicedness. Qualitative Research, 15(6), 670–687.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (M Holquist, Ed.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics (C. Emerson, Ed. and trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres & other late essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Blackler, F. (2009). Cultural-historical activity theory and organization studies. In A. Sannino, H. Daniels, & K. D. Gutiérrez (Eds.), Learning and expanding with activity theory (pp. 19–39). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). The Iron cage revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality. In W. W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747 .

Engeström, Y. (1987/2015). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2011). Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(3), 368–387.

European Commission. (2013). Guide to social innovation. Brussels: EU Commission. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/library/guide-social-innovation_en. Accessed 1 Aug 2020.

Fazel, S., & Wolf, A. (2015). A systematic review of criminal recidivism rates worldwide: Current difficulties and recommendations for best practice. PLoS ONE, 10(6), 1–8.

Graunbøl, H. M., Kielstrup, B., Muiluvuori, M.-L., Tyni, S., Baldursson, E. S., Gudmundsdottir, H., Kristoffersen, R., Krantz, L., & Lindsten, K. (2010). Retur: En nordisk undersøkelse af recidiv blant klienter i kriminalforsorgen. Oslo: Kriminalomsorgens utdanningssenter. Available at https://krus.brage.unit.no/krus-xmlui/handle/11250/160672.

Hean, S. (2015). Strengthening the links between practice and education in the development of collaborative competence frameworks. In Interprofessional education in Europe: Policy and practice (pp. 9–32). Garant. ISBN 9044133349.

Hean, S., Staddon, S., Clapper, A., Fenge, L. A., Heaslip, V., & Jack, E. (2014). Improving collaborative practice to address offender mental health: Criminal justice and mental health service professionals’ attitudes towards interagency training, current training needs and constraints. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education.

Hean, S., Warr, J., Heaslip, V., & Staddon, S. (2011). Exploring the potential for joint training between legal professionals in the Criminal Justice System and health and social care professionals in the Mental-Health Services. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 25(3), 196–202.

Hean, S., Willumsen, E., Ødegård, A., & Bjørkly, S. (2015). Using social innovation as a theoretical framework to guide future thinking on facilitating collaboration between mental health and criminal justice services. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 14(4), 280–289.

Hean, S., Willumsen, E., & Ødegård, A. (2017). Collaborative practices between correctional and mental health services in Norway: Expanding the roles and responsibility competence domain. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(1), 18–27.

Hean, S., Willumsen, E., & Ødegård, A. (2018). Making sense of interactions between mental health and criminal justice services: The utility of cultural historical activity systems theory. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 14(2), 124–141.

Hean, S., Lahtinen, P., Dugdale, W., Larsen, B. K., & Kajamaa, A. (2020). The Change Laboratory as a tool for collaboration and social innovation. In Samskaping: sosial innovasjon for helse og velferd (pp. 207–221). Universitetsforlaget.

Heaslip, V., Hean, S., & Parker, J. (2016). The etemic model of Gypsy Roma Traveller community vulnerability: Is it time to rethink our understanding of vulnerability? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, 3426–3435.

Jewkes, Y. (2012). Autoethnography and emotions as intellectual resources: Doing prison research differently. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(1), 63–75.

Kerosuo, H., & Engeström, Y. (2003). Boundary crossing and learning in creation of new work practice. Journal of Workbased Learning, 15, 345–351.

Kodner, D., & Spreeuwenberg, L. C. (2002). Integrated care: Meaning, logic, applications, and implications—A discussion paper. International Journal of Integrated Care, 2, 1–6.

Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organization and environment: Managing differentiation and integration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Liebling, A., Elliot, C., & Price, D. (1999). Appreciative inquiry and relationships in prisons. Punishment & Society, 1(1), 71–98.

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service (30th Annual ed.). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Markova, I. (2016). The dialogical mind: Common sense and ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McQuillan, M. (2019, December 2). London Bridge attack: Profound questions for higher education. Research Professional News. Available at https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-uk-views-of-the-uk-2019-12-london-bridge-attack-profound-questions-for-higher-education/. Accessed Aug 2020.

Miller, D. (2001). Distributing responsibilities*. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 9(4), 453–471.

Ministry of Justice, UK. (2013). Transforming rehabilitation: A strategy for reform transforming rehabilitation: A strategy for reform. London: Ministry of Justice. Available at https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/transformingrehabilitation/results/transforming-rehabilitation-response.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Pratt, J. (2008). Scandinavian exceptionalism in an era of penal excess: Part I: The nature and roots of Scandinavian exceptionalism. British Journal of Criminology, 48(2), 119–137.

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Planning, 4, 155–169.

Sannino, A., Engeström, Y., & Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25(4), 599–633.

Skardhamar, T., & Telle, K. (2012). Post-release employment and recidivism in Norway. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28, 629–649.

Sloan, J., & Wright, S. (2015). Going in green: Reflections on the challenges of ‘Getting In, Getting On, and Getting Out’ for doctoral prison researchers. In D. H. Drake, R. Earle, & J. Sloan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of prison ethnography. Basingstoke: Palgrave Handbooks.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Virkkunen, J., & Newnham, D. S. (2013). The change laboratory. CRADLE: Helsinki.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

The editors contributed equally to the production of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hean, S., Kajamaa, A., Johnsen, B., Kloetzer, L. (2021). Setting the Scene and Introduction. In: Hean, S., Johnsen, B., Kajamaa, A., Kloetzer, L. (eds) Improving Interagency Collaboration, Innovation and Learning in Criminal Justice Systems. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70661-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70661-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-70660-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-70661-6

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)