Abstract

In this chapter I present an overview of contract cheating in Canada over half a century, from 1970 to the early 2020s. I offer details about a failed attempt at legislation to make ghostwritten essays and exams illegal in Ontario in 1972. Then, I highlight a 1989 criminal case, noted as being the first of its kind in Canada, and possibly the Commonwealth, in which an essay mill owner and his wife were charged with fraud and conspiracy. The case was dismissed by the judge, leaving the contract cheating industry to flourish, which it has done. I synthesize the scant empirical data available for Canada and offer an educated estimate of the prevalence of contract cheating. Finally, I conclude with a call to action for educators, advocates, and policy makers. I conclude with a call to action for Canadians to take a stronger stance against contract cheating.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In this chapter, I present an overview of contract cheating in Canada, exploring its history and the extent of the problem today. Less is known about contract cheating in Canada compared with other countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom (UK), where contract cheating research and advocacy have matured since the early 2000s (Bretag, 2016, 2019; Lancaster & Clarke, 2007; Newton, 2018; Newton & Lang, 2016; Rogerson & Basanta, 2016). There are multiple reasons why Canada lags behind including the lack of: (a) widespread media coverage; (b) advocacy and education by quality assurance bodies; and (c) research funding and support.

To begin this chapter I point out that although the term “contract cheating” has been widely used internationally for more than a decade (Lancaster & Clarke, 2007), it is still gaining traction in Canada. Canadians may be more familiar with phrases such as “term paper mill” or “essay mill”, but the global community has recognized that the term “contract cheating” is more accurate, since it covers the outsourcing of all kinds of the academic work, encompassing both text-based and non-text based assessments, including for example, computer coding assignments (Lancaster & Clarke, 2017). It is essential to recognize that the contract cheating industry is global and operates on a massive scale, and has been estimated to be valued at $15 Billion USD (Eaton, 2021). The proliferation of early industry in the United States (US) in the 1970s is well-documented, leading to a naïve and erroneous assumption that early term paper mills flourished in America but that Canada was spared. There is ample evidence to show that commercial contract cheating was also active in Canada. In what is perhaps the most extensive and detailed history of the contract cheating industry in Canada, Buerger (2002) dedicated an entire chapter of his doctoral thesis to the topic, going to extensive lengths to conduct archival research, review legal documents and interview individuals involved in the industry, including key informants in a sting operation against an essay mill dealer in Toronto in the 1980s.

In this chapter, I synthesize what is known about the contract cheating in Canada. First, I provide a historical overview of the industry in Canada, including a failed attempt to make contract cheating illegal in Canada in the 1970s; and a subsequent landmark case to lay criminal charges against an essay mill in the 1980s. Following, I detail how the industry has grown and discuss why Canada continues to lag behind other countries in terms of research and advocacy. Next, I discuss what Canadians have been doing in recent years to catch up to other countries and how our efforts are becoming more systematic and organized across the country. I conclude with a call to action about what can be done to advance contract cheating advocacy, education, policy, and scholarship in Canada.

Canada’s Connection to Early American Term-Paper Mills

The commercial essay mill industry began as early as the 1930s (Buerger, 2002), and was firmly established across the US and Canada in the 1960s and 1970s, with states along the Eastern Seaboard of the US being a hub for early term paper services (Buerger, 2002; Goodman, 1971a, b, c; Hechinger, 1972, Maeroff, 1971). As evidence of Canadian activity in the contract cheating industry, student newspapers, such as the Varsity at the University of Toronto, were running advertisements for ghost-written essays in the 1960s (Buerger, 2002).

American term-paper mills became hot news in the early 1970s, and reporters were quick to point out that Canadians were among those supplying services to the industry that was flourishing across the border (Goodman, 1971c; Shephard, 1972). In a six-page exposé in Cosmopolitan magazine in March 1973, journalist Jack Shepherd reported that:

Termpapers Unlimited, Inc., [was] a nationwide operation run by Ward Warren, a self-made millionaire at twenty-three. The company employs some 3,000 ghosts [ghostwriters] during the academic year who toil in every major U.S. and Canadian city, cranking out, by Warren’s own estimation, “90% of all the term papers now being disseminated in the country.” (Shepherd, 1973, p. 172). (Emphasis added)

By 1972, US state judges were ordering term paper mills to close, effectively making it illegal for these businesses to operate in particular states (Waggoner, 1972). This merely prompted business owners to close down their business in one state and move to another where it was not illegal to operate, catalysing the growth of the industry across North America.

1970s: Canada’s Commercial Term Paper Mills and “A Bill to Stop Essay Sellers”

Journalists began sounding the alarm about the commercial term paper mills in Canada in the 1970s in articles published by major newspapers, including in the Calgary Herald (Buchwald, 1972; Dallos, 1972) and in Canada’s national newspaper, the Globe and Mail (O’Toole, 1974; Screening out the cheat, 1972; Would have to keep records: A bill to stop essay sellers, 1972; Wright, 1974). Since the 1970s, there have been repeated news reports of contract cheating companies operating openly in cities across Canada, including a television news story from CTV Edmonton, entitled “Essays for Sale”, that won the Radio-Television News Directors Association Dan McArthur Award for in-depth and investigative journalism (RTNDA Canada announces, 2006 Prairie Regional Award Recipients, 2007).

The press has long served as an early alert system for unethical practices in education that merit the attention of the public, as well as those in decision-making roles who can effect change (Eaton, 2020c; Eaton & Turner, 2020). An analysis of historical newspaper records show that American suppliers were selling to Canadian customers, but that Canada also had its own home-grown essay mills owned and operated by and for Canadians. I elaborate on this point later.

Just as Americans were taking legal action against term paper mills operating on the Eastern Seaboard of the US, similar legislative initiatives were underway in at least one Canadian province, though with less success. In April 1972, the Globe and Mail reported that, “the Ontario Legislature is now toying with the idea of a law to stop firms from ghost-writing papers for students, perhaps by way of a charge of fraud or complicity, if a student were to testify that a paper was purchased and for what reasons” (Screening out the cheat, 1972, p. 6).

A few months later, the proposed bill made national news when it was reported on page five of the national newspaper, under the title “Would have to keep records: A bill to stop essay sellers” (1972). The report, with no author indicated, got a few of the details incorrect, and the correct details are archived online in legislative documents as a matter of public record. A review of the legislative documents shows that on June 14, 1972, a private member’s bill was introduced by Member of the Provincial Parliament (MPP), the Honourable Albert Roy (Roy, 1972). Bill 174, An Act Respecting Ghost Written Term Papers and Examinations received a first reading in the legislature. The official report of the debate (i.e., the Hansard), recorded the introduction of the bill as follows:

Mr. Roy moves first reading of bill intituled, An Act respecting Ghost-Written Term Papers and Examinations, 1972.

Motion agreed to; first reading of the bill.

Mr. Roy: Mr. Speaker, this bill enables the Attorney General, on the request of the Minister of Colleges and Universities (Mr. Kerr), or the Minister of Education (Mr. Wells), to bring a civil action in the Supreme Court to stop operations of a corporation, or business, which deals in ghost-written term papers or examinations.

Mr. Shulman: It should also outlaw politicians’ ghost-written speeches! (Legislative Assembly of Ontario Official report of debates (Hansard), 1972 p. 3651)

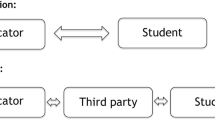

There is no evidence to suggest that the proposed legislation made it past a first reading (K. Laukys, personal communication, December 21, 2020). Although the bill was never passed, it is notable that it endeavoured to curb not only term papers written by third parties, but also examinations, which suggests that the practice of hiring impersonators to write one’s exams in Canada has been a concern for many decades.

Early suppliers to the industry shared their experiences publicly, providing historical accounts of how the businesses operated, including costs and payments to suppliers. In an exposé published in Canada’s national newspaper, the Globe and Mail, a writer who supplied services to the local industry in Toronto in the 1970s revealed that:

The essay bank charges students according to their academic level (it’s $4.95 a page for first, second and third year original papers and escalates after that; it’s $2.75 a page for ready-made essays already in the bank). The student must supply all reference books and the writer must come in, pick them up and get the thing written for deadline. All business is done either by phone or in the essay bank’s office. (O’Toole, 1974, p. 45)

Presumably, the prices indicated were in Canadian dollars, as the article was written in Canada about a term paper mill in Toronto. This may be the earliest available evidence regarding the prices of outsourced academic work in Canada. To put these prices in historical perspective, the average income for a family of two or more persons in Canada in 1974 was $16,147 CAD (Statistics Canada, 1977) and a pound of hamburger cost about $1.29 CAD (Stewart, 1974).

O’Toole (1974) indicated that term paper mills had walk-in stores operating in Toronto, similar to the ones operating in the US. In other words, the commercial contract cheating industry has been actively operating in Canada since the 1970s, and possibly even earlier; and it would be naïve and erroneous to claim that early term paper mills were exclusively an American phenomenon. A story in the Globe and Mail near the end of the decade declared that the essay mill business was “dying out” (Stead, 1978, p. 5), but evidence shows otherwise.

The 1980s: The Case of Custom Essay Service

The 1980s brought a landmark case against Custom Essay Service (CES), believed to be “Canada’s oldest term paper mill” (Schmidt, 1998, C8), which had allegedly been operating since at least the 1970s. Buerger (2002) investigated the case in great detail, interviewing a number of individuals directly involved and conducting an analysis of primary documents never released to the public. Among those he interviewed were Detective Graham Hanlon at 31 Division and Sergeant Brian Dickson at 21 Division of the Metropolitan Toronto Police (now known as the Toronto Police Service), who led the sting operation that resulted in charges. Buerger (2002) also interviewed the Associate Dean of Students at York University, Mark Webber, who was instrumental in working with the police to have charges laid.

At the request of York University in 1988 the Toronto police began investigating CES, run by Derek and Marilyn Sim of Sunderland, Ontario (Buerger, 2002; Couple charged in essay scam, 1989). An initial investigation from the Fraud Division was unsuccessful, and the university “turned to attorney Neil Kosloff, who approached Crown Attorney Steven Leggett, who in turn convinced 31 Division that a prosecution on the grounds of uttering forged documents had merit” (Buerger, 2002, p. 302). The case was assigned to Dickson and Hanlon, who met with administrators at York in July of 1988 to determine how to proceed, and a sting operation was designed (Buerger, 2002).

Constable Suzanne Beauchamp was recruited to place an order with CES for Sociology 1010.06A, a course she had actually taken when she was a student at York herself, so she could speak legitimately about the course and the kind of paper required (Buerger, 2002). After successfully purchasing the essay, a Criminal Code search warrant was issued to the police. Based on interviews with individuals directly involved in the case, Buerger wrote that on “April 5 [1989], Dickson and Hanlon, accompanied by uniformed officers and Weber, raided the CES premises at 4 Collier Street and seized ‘boxes and boxes and boxes’ of term papers and, more significantly, order forms” (Buerger, 2002, p. 303).

The raided documents showed that during the three-month period from January to April 1989, approximately 530 order forms were on file, representing a gross income of $98,000 (CAD), about half of which was kept by co-owners Derek Robinson Sim and Marilyn Elizabeth Sim (Buerger, 2002). This is notable because if that three-month period was indicative of a typical business quarter, we can extrapolate this figure to estimate that the business was grossing revenues of about $392,000 (CAD) per year. It is not known how many essay mills were operating in Canada in the late 1980s but, based on evidence from this one police investigation, it is reasonable to estimate that essay mills in Toronto alone were taking in well over a million dollars per year by 1989.

The Sims were charged with one count of conspiracy to utter forged documents and seven counts of uttering forged documents (Beurger, 2002; Couple charged in essay scam, 1989) in what was believed be to be “the first case of its kind in Canada and in the Commonwealth” (Schmidt, 1998). The prosecution prepared a strong case and “were prepared to bring forward two dozen witnesses, including eight students who had purchased essays, university faculty who had received them, and even a disaffected former CES writer” (Beurger, 2002, pp. 304–305). The case was heard by Judge George E. Carter, who ultimately dismissed the charges on September 11, 1990, finding there was no intent to commit a criminal act (Beurger, 2002).

Although CES “escaped without penalty” (Beurger, 2002, p. 307), the students who were involved were not so lucky. Over 100 students faced academic misconduct disciplinary consequences, and all were found responsible and subjected to sanctions ranging from receiving a grade of zero on the assignment to a 10-year suspension from the university (Beurger, 2002). The contract cheating industry in Canada continued to flourish and there is evidence to suggest that CES itself continued to operate successfully well into the Internet era (see Schmidt, 1998).

The 1990s: An Exposé and the Impact of the Internet

In a nine-page exposé in Harper’s Magazine in 1995, a writer supplying services to the contract cheating industry in Canada elaborated on her experiences. Writing under the pseudonym of Abigail Witherspoon, the writer provided extensive and exacting details about working for ‘Tailormade’, also a pseudonym, for an essay service in “a large Canadian city” (Witherspoon, 1995, p. 49), which was later determined to be written about CES (Buerger, 2002). The business was touted as being “Canada’s foremost essay service” (p. 49) by the owner’s wife, who answers the phone when calls come in. The writer explained how “orders came in from Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg” (p. 49) and how the crew of writers employed by the business “often wait at a bar around the corner” from the office, where the company has a regular table where writers gather to await their next assignment (Witherspoon, 1995, p. 50).

According to Witherspoon, writers supplying services to the company allegedly included “a professor who’d been fired from some school, we were never really sure where…” (p. 51) who eventually “started an essay-writing service of his own” (p. 51) and went on to become “Tailormade’s main competition” (p. 51).

By 1995, Tailormade was allegedly charging “twenty dollars Canadian a page for first- and second-year course assignments, twenty-two a page for third- and fourth-year assignments, twenty four for ‘technical, scientific, and advanced’ topics.” (p. 51), of which “the writers get half, in cash: ten and eleven bucks a page; twelve for the technical, scientific, and advanced” (p. 52). Students who allegedly did not bring in books and other reference materials to help the writers were charged an additional $2 per page (Witherspoon, 1995).

Witherspoon describes a life of pulling two to three all-nighters a week during peak times, fueled by licorice and extra strong coffee, eager to be assigned rush jobs, for which she was paid an extra dollar per page (Witherspoon, 1995). She reports that the assignments she disliked the most were from education students that “all involve writing up our customers’ encounters in their ‘practicum’”… including, “‘reflections’ on a ‘lesson plan’ for a seventh-grade English class” (p. 55). She then goes on to offer a direct quotation from a lesson plan she allegedly wrote for a teacher trainee.

Witherspoon further details how she wrote application essays for applicants to Canadian medical schools, describing her work as “academic prostitution” (p. 56) in what has been, to date, the most detailed account on record of a writer working for a Canadian essay mill. Three years after that exposé was published, Derek Sim was reported to be working from a “crammed, one-room office equipped with a fully-wired computer” (Schmidt, 1998, p. C8), having moved the business fully online in the age of the Internet.

The development of the Internet changed how contract cheating occurred all over the world, including in Canada. In the 1990s and early 2000s, there were numerous news stories, not only in Ontario, but across Canada about the term-paper industry moving online (Cribb, 1999; Ellingson, 2003; Gray, 2002; Mah, 1999; Maich, 2006; Pearson, 2002; Steffenhagen, 2001; Walker, 2001). There is at least one public account of students at the University of Alberta being disciplined for buying term papers from the Internet in the 1990s (Mah, 1999).

The 2000s: Research, Advocacy, and Collaboration

As in decades past, journalists across the country continued to publish stories about academic outsourcing, though by the turn of the millennium, most of the stories focused on Internet-based services (Ellingson, 2003; Maich, 2006; Steffenhagen, 2001; Walker, 2001).

A Focus on Research: Contract Cheating Data From Canada

The first decade of the new millennium brought research about academic outsourcing into sharper focus. Mentions of Internet term paper mill use among Canadian students began to appear in scholarly and professional journal articles (see Oliphant, 2002). Term paper mills were renamed when two computer science professors in England discovered that their students were outsourcing their coding assignments over the Internet. They proposed contract cheating as an umbrella term for all kinds of outsourced assignments (Clarke & Lancaster, 2006). News of their investigation was covered by the BBC (2006) and the two went on to systematically study the phenomenon of contract cheating, laying a foundation for researchers elsewhere to build similar programs of research. In Canada, TV coverage of term paper mills (e.g., Lee, 2012) happened at a local level and did not ignite large-scale action against contract cheating in the same way that news stories in Australia and the UK did.

Lancaster and Clarke repeatedly identified that Canada was among the top four countries from which students placed online orders for computer science assignments (Clarke & Lancaster, 2006; Lancaster & Clarke, 2007, 2009). The top three were the US (#1), the UK (#2), and Australia (#3). Canadian computer science students were found to have ordered 6.8% of the total number of orders placed on the website, with orders originating from students at 19 different Canadian institutions (Lancaster & Clarke, 2007). One limitation to their data was that it was specific to computer science students but is nevertheless appropriate to establish from an empirical standpoint that Canada has been among the top countries from which students buy their academic work.

The seminal research by Christensen Hughes and McCabe (2006a, b) provided the most comprehensive data set about academic misconduct in Canadian higher education to date. Among respondents at 10 different institutions, 8% of undergraduate students and 3% of graduate students self-reported that they had turned in work completed by someone else (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006a). Five percent of undergraduates and 4% of graduate students admitted to having written or providing a paper for another student (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006a). Christensen Hughes and McCabe (2006a) found that 1% of undergraduate students and 1% of graduate students admitted to buying academic work from an online term paper mill or website in the early 2000s.

More than a decade later, Stoesz and Los (2019) replicated the survey administered by Christensen Hughes and McCabe in two different studies, both with students working towards high school completion. Their results revealed that as many as 17.9% of research participants self-reported having turned in papers obtained from a contact cheating company that charged a fee, though results varied across age groups.

A comparison between the two studies is not without its problems but is nevertheless a useful exercise. Focusing specifically on the question related to students to self-reported that they bought academic work from an online term paper mill or website, in the 13-year gap between the two studies, the number rose dramatically (see Table 8.1).

The Christensen Hughes and McCabe (2006a) study had a larger sample size and was conducted across Canada. They grouped results by the learning experiences students were reflecting on (i.e., high school, undergraduate, or graduate). Stoesz and Los’s (2019) sample size was much smaller and focused only on students in the western Canadian province of Manitoba. In addition, their study focused on individuals taking junior high and high school courses (even the 28–32 year-olds studying at adult education centres). Stoesz and Los (2019) did not collect data from students enrolled in post-secondary courses.

What we know for certain at this point is that Canada lacks current accurate data about the prevalence of contract cheating on a national scale. Although there are indications that if we were to replicate the Christensen Hughes and McCabe (2006a) study (or parts of it) today the results might differ from what they were in the first few years of the new millennium when they collected their data, we cannot draw such a conclusion from a scientific standpoint. At best, we can make an educated guess. That is what I endeavoured to do a few years ago (Eaton, 2018). I created a model for understanding the probability of the extent of contract cheating in Canada that could be replicated over time.

I drew from Curtis and Clare’s (2017) meta-analysis of previously collected data sets (N = 1,378) from studies around the world. They found that 3.5% of students, on average, engaged in contact cheating, though they noted some variances among sub-groups. I then mapped that percentage to Statistics Canada data about postsecondary enrollments across the country to arrive at an educated estimate that the number of post-secondary students engaging in contract cheating was 71,223 (see Eaton, 2018).

I selected Statistics Canada as the source of the post-secondary enrollments deliberately, as it is a reliable source of statistics with data collected in a consistent manner over time. Any changes in how they change their collection methods or presentation of the results is explained in detail and publicly available. This allows us to draw on the most statistically accurate data available. Since I conducted my initial estimate, Statistics Canada has updated their statistics for post-secondary enrollments in Canada to include data from the 2018–2019 academic year (Statistics Canada, 2021). Using these most recent statistics and Curtis and Clare’s (2017) 3.5% figure as the average prevalence of contract cheating, I have estimated that over 75,000 post-secondary students engaged in contract cheating in the 2018–2019 academic year (see Table 8.2).

Values rounded up to the nearest whole number.

I emphasize that this is an estimate based on previously published scientific estimate and does not represent an estimate of actual rates of contract cheating based on Canadian data. These statistics were also published pre-COVID and at the time this book was published, we had no empirical data about the extent to which contract cheating may have increased during the pandemic in Canada. There remains a dearth of data about contract cheating in Canada and there is an urgent need to remedy this.

A Focus on Advocacy and Collaboration

In 2008, the Academic Integrity Council of Ontario (AICO) was launched (McKenzie et al., 2020a), a provincial network that “has provided a forum for academic integrity practitioners and representatives from post-secondary institutions in Ontario to share information, and to facilitate the establishment and promotion of academic integrity best practices” (p. 25). In 2018, AICO launched a contract cheating sub-committee, which included representatives from six member institutions in the province and included a five-point action plan focused on building awareness, sharing resources and, engaging in advocacy (Academic Integrity Council of Ontario, 2018, 2019b; McKenzie et al., 2020a).

The first available evidence of Canadian collaboration with an international colleague is that of Corinne Hersey, a graduate student at the University of New Brunswick, who co-presented with Thomas Lancaster at a conference in the UK (Hersey & Lancaster, 2015). The emergence of graduate student research into contract cheating in Canada holds much promise for the future of academic integrity in Canada, but their work needs to be supported so they can develop sustained programs of research beyond graduation (Eaton & Edino, 2018).

In 2018, the Canadian Consortium of the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI, 2018a, b) focused on contract cheating at its annual meeting that year which is normally held as a pre-conference event prior to the centre’s annual conference (Canadian Consortium—ICAI, 2018a, b; Miron & Ridgley, 2018). The following year, contract cheating continued to be a topic of interest, with AICO presenting a report of its sub-committee activities since it had been convened (AICO, 2019a).

The inaugural Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity (2019) held at the University of Calgary provided a unique opportunity for scholars, students, and professionals to mobilize and share research and practical experience about contract cheating in Canada. Tracey Bretag focused on contract cheating in her keynote presentation (Bretag, 2019a) and Thomas Lancaster provided a feature session on the topic (Lancaster, 2019). In addition, there were a number of additional sessions presented on contract cheating (Blackburn, 2019; Eaton, 2019b; Hersey, 2019; Thacker et al., 2019; Usick et al., 2019, 2020). The symposium provided a unique opportunity for Canadians to dialogue about contract cheating in a way that no previous event had. During the symposium, AICO members facilitated a workshop on how to establish a regional academic integrity network (Ridgley et al., 2019). As a result, three new provincial networks were established in the six months following the symposium: the Alberta Council on Academic Integrity (ACAI); the British Columbia Academic Integrity Network (BC AIN); and the Manitoba Academic Integrity Network (MAIN) (see Stoesz et al., 2019b). The Manitoba group quickly established themselves as national leaders with a multi-institutional collaborative project to block the uniform resource locators (URLs) of contract cheating websites from being accessed on campuses (Seeland et al., 2020a; b). A few provinces to the west, the Alberta Council on Academic Integrity (Eaton et al., 2020a) established a working group (similar to AICO’s sub-committee) to focus specifically on contract cheating. These initiatives demonstrate that contract cheating is an urgent and important issue in Canada.

Institutions across Canada have participated in the International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating since it began in 2016 (Mourelatos, 2020). Every year since, this global day of advocacy has been organized by the ICAI to promote awareness about contract cheating, with a variety of events being held on campuses and online. In 2020, Canadians collaborated on a national scale, when the entire event went virtual due to COVID-19, and the international program committee was chaired by a Canadian, Jennie Miron (Miron, 2020).

Developing a Canadian Research and Advocacy Agenda for Academic Integrity

Canadian researchers and practitioners have increased their momentum around contract cheating research and advocacy since about 2018, the year AICO launched its subcommittee on contract cheating and researchers and advocates began publishing about contract cheating in Canada specifically (Chang, 2018; Eaton, 2018; Flostrand, 2018). One observation of note about these initial research articles about contract cheating in Canada is that the authors were mostly unknown to one another, as they worked in different disciplines such as second languages (Chang, 2018), business (Flostrand, 2018) and education (Eaton, 2018). Canadians are now developing a strong and sustainable research community at a national level to address contract cheating. It is evident that Canada needs a robust community of scholars and advocates to build capacity and community if we are to make progress combatting contract cheating in Canada.

National Policy Analysis Project

In 2018, I developed a research project to better understand how contract cheating was addressed in academic misconduct policies across publicly funded Canadian postsecondary institutions (Eaton, 2019a). The project was modelled after research undertaken some years earlier in Australia (Bretag et al., 2011a, b; Grigg, 2010). I was fortunate to be mentored by Tracey Bretag on how to develop and implement the project (Eaton, 2020d; Eaton et al., 2020b). As a result of Bretag’s advice, I divided the project into phases, based on region and institution type (e.g., universities and colleges).

At the time of this writing, different teams have undertaken an analysis of 67 institutional policies across five provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario) including colleges (n = 22) and universities (n = 45). We have three peer-reviewed conference presentations (McKenzie et al., 2020b; Thacker et al., 2019a, b) and two refereed articles (Stoesz et al., 2019a; Stoesz & Eaton, 2020), with another under development. As of mid-2021, we are in the midst of our academic integrity policy analysis of universities in Atlantic Canada, which will bring the total number of institutions included in this study up to 80. Through this project we are building a network of researchers across Canada who are developing experience and expertise collaborating on academic integrity and contract cheating research. Our intention is that we will be able to leverage this experience going forward to position ourselves for national-level research funding.

Development of Resources

In addition to research, Canadians are beginning to develop resources on contract cheating that can be shared among members of the academic integrity community. AICO created a student tip sheet, which they released in time for the International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating in 2020 (Miron & McKenzie, 2020). In addition, others have created resources to raise awareness about contract cheating in higher education (Stoesz et al., 2019c) and assist educators and administrators with recognizing and managing cases of it (Eaton, 2019c; 2020a). In 2021, members of the Alberta Council on Academic Integrity created a one-page synopsis of an analysis of the parallels between the contract cheating industry and organized crime (Grue et al., 2021).

The development of such resources is important because it means that Canadians must no longer rely on resources created in other countries, where educational systems differ. Although there can be value in using a variety of resource material as a reference point, it is nevertheless helpful to have country-specific support materials. A key point of note is that the resources created to date in Canada have been developed by individuals, often in collaboration with provincial networks, whereas in other countries such as Australia and the UK, quality assurance bodies have developed resources that they have made freely and publicly available and have put effort into promoting and sharing them widely (see, for example, TEQSA, 2017, 2020; QAA, 2020).

Role of Quality Assurance (QA) Bodies

As of 2021, bodies that oversee quality assurance in Canadian higher education had yet to produce resources related to contract cheating, or to play an active role in addressing it. The International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (2020) highlighted the Alberta network as an international exemplar of excellence in their Toolkit to Support Quality Assurance Agencies to Address Academic Integrity and Contract Cheating. “Assess the Sector” (see International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education, 2020). In the toolkit, quality assurance agencies are encouraged to connect with networks such as the Alberta Council “that will allow you to identify and respond to emerging issues” (p. 26).

Canada’s lack of action stands in stark contrast to advocacy and education being led by quality assurance bodies in the United Kingdom (Quality Assurance Agency, 2020) and Australia (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency, 2015, 2017, 2020). Efforts in Australia to act against contract cheating have been so successful that legislation to make it a criminal offense to supply academic cheating services came into effect in 2020 (Parliament of Australia, 2020). In the discouraging and enduring absence of legislation in Canada to combat this predatory industry, it is crucial for educational quality assurance agencies in Canada to take a strong stand against contract cheating and to bring about change. Further, it is evident that in countries where there is a national quality assurance body for higher education, such as Australia and the UK, significant progress has been made more quickly than in countries where educational quality assurance is addressed at a regional or state level. It is essential that quality assurance bodies across Canada coordinate their efforts and support one another in taking action, so the result is a national stance against contract cheating.

The Impact of COVID-19

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on contract cheating has yet to be fully understood, given this book was written in 2020 and early 2021, with many of its contributors working or studying from their homes instead of from their campuses. COVID-19 revealed a variety of flaws in society in general, and education was not spared. Rates of academic misconduct increased around the world during the pandemic, and Canada was no exception (Basken, 2020; Eaton, 2020b).

Contract cheating, including commercial file-sharing companies and unethical tutoring, became amplified during the pandemic (Eaton, 2020c; Eaton & Turner, 2020), along with remote online proctoring (e-proctoring) of exams. Although online proctoring has nothing to do with contract cheating per se, one common feature between e-proctoring and contract cheating is the positioning of commercial entities as providing quick and easy solutions to academic misconduct during a moment of crisis. In turn, these third-party vendors collect student data on a massive scale, without students necessarily being aware of how their information is being used or who has access to it. Issues such as privacy and illicit use of students’ data are questions beyond the scope of this chapter but suffice to say that they matter and neither educators nor students can afford to remain naïve to these issues (Gray, 2022).

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have endeavoured to synthesize what is known about contract cheating in Canada to date. It is a myth that contract cheating has not existed in Canada. Not only have commercial contract cheating vendors been actively operating in our country for more than half a century (and quite possibly even longer), but they also operate at scale and continue to prey on our students at every level, starting as young as elementary schools and in both official languages (Eaton & Dressler, 2019).

Limitations

COVID-19 resulted in particular limitations to this chapter, as access to original legislative and court documents was not permitted during this time. Much of what is known about the legal case in the 1980s against CES was meticulously documented by Geoffrey Buerger (2002) in his doctoral thesis. Nevertheless, consulting primary sources is preferable, but it was not possible during the coronavirus pandemic.

Due to my own limited language proficiency in French, all of the source materials I consulted were in English. Although there is strong evidence to suggest that contract cheating occurs in a variety of languages other than English (Eaton & Dressler, 2019), there is much work to be done to understand how contract cheating impacts those in Francophone regions of the country.

Call to Action

I conclude this chapter with an urgent call to action. We have much work to do in Canada not only raise awareness about contract cheating, but to take action against it. My recommendations include:

Student Advocacy

Because contract cheating companies prey on students, it is essential for students not only to be actively involved in advocacy efforts, but also to lead them. Student governments and provincial and national student leadership bodies are key stakeholders in the conversation about contract cheating specifically, and academic integrity generally. It is incumbent upon educators and administrators to include students in policy-making decisions about academic misconduct and involve them in advocacy work.

Research

Academic integrity research in Canada has lacked funding on a national scale (Eaton & Edino, 2018). The absence of federal research funding is one of the reasons that Canada lags behind countries such as Australia, where research programs on contract cheating have been well funded. It is imperative for funding bodies such as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and other national-level bodies to sponsor research on contract cheating.

Along the same vein, it is essential for Canadian researchers to undertake collaborative, multi-institutional, and multi-jurisdictional research projects. Although individual research projects are an excellent place to start, for research to have more impact, it is essential for researchers to work collaboratively on larger national-level projects.

Support for Graduate Students

It is essential to support graduate students who wish to study contract cheating in Canada. Only a handful of Canadians who have undertaken academic integrity study for their doctoral work have gone on to develop sustained programs of research on the topic. This must change in order for the field of academic integrity research to mature. Contract cheating continues to be an urgent issue and it is imperative for professors and university departments (particularly faculties of education) to actively support graduate student education and research.

Quality Assurance and Professional Bodies

As long as quality assurance bodies are not involved in efforts to address contract cheating, educational institutions may have little incentive or power to act. It is essential for the organizations responsible for the oversight of quality assurance of education in Canada to provide leadership and guidance regarding contract cheating, as well as to develop resources and supports to address it.

Professional regulatory bodies, such as those of engineering, nursing, and teaching, are key community stakeholders. When students engage in contract cheating, they are not earning their credentials legitimately. The result can be that graduates of reputable schools may lack the skills necessary to serve in the profession. Even worse, they may have developed habits of unethical and deceptive behaviour that they may carry forward into their professional practice. It is imperative for accrediting and professional bodies to hold schools accountable for the ways in which they uphold integrity. A particular focus on contract cheating is needed as part of that accountability.

Build Momentum and Sustain Our Actions

As I have shown in this chapter, Canada is not immune to contract cheating. Canadian educators, advocates and scholars have begun to mobilize and collaborate on a larger scale over since about 2018. It will be essential for us to ensure our efforts are sustainable over time. Although we have a few strong advocates working tirelessly to organize and encourage others, every community, every school, every quality assurance and professional body, and every political party needs individuals committed to tackling this contract cheating in Canada.

Legislation

As more countries take legislative action against contract cheating, Canada falls further behind. The issue of contract cheating needs to be on political agendas. To get it there, executive institutional leaders can help ensure that contract cheating is part of discussions with government. One approach that has been successfully used in countries such as Australia is to focus on the predatory nature of commercial third-party vendors who prey on our students.

2022 will mark 50 years since the first failed attempt to pass legislation to make it illegal to sell ghostwritten term papers (Roy, 1972). Even if that first effort was unsuccessful, it is not insignificant. It will be important to mark the 50th anniversary of that 1972 attempt to have legislation passed. We can celebrate the efforts of those who came before us and commit to carrying on the work they started until we are successful in legislating against contract cheating in Canada. More than ever before Canadians are poised to take a strong and united stance against contract cheating and now is the time to do so.

Notes

- 1.

Values rounded up to the nearest whole number.

- 2.

Statistics Canada (2021) note: “All counts are randomly rounded to a multiple of 3 using the following procedure: counts which are already a multiple of 3 are not adjusted; counts one greater than a multiple of 3 are adjusted to the next lowest multiple of 3 with a probability of two-thirds and to the next highest multiple of 3 with a probability of one-third. The probabilities are reversed for counts that are one less than a multiple of 3.” This resulted in a difference of 3 in the total number of enrollments. See Statistics Canada (2021) source data for further details.

References

Academic Integrity Council of Ontario (AICO). (2019a). AICO Contract Cheating Sub-Committee Report. Paper presented at the Canadian Consortium—International Center for Academic Integrity. https://live-academicintegrity.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Contract-Cheating_ICAI-Canadian-Consortium_March-2019.pdf

Academic Integrity Council of Ontario (AICO). (2019b). AICO’s Subcommittee on contract cheating. Retrieved January 3, 2021, from https://academicintegritycouncilofontario.wordpress.com/contract-cheating/

Academic Integrity Council of Ontario (AICO). (2018). Annual report 2017/2018. Retrieved from https://academicintegritycouncilofontario.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/academic-integrity-council-of-ontario-annual-report-2017-18.pdf

Basken, P. (2020, December 23). Universities say student cheating exploding in Covid era. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/universities-say-student-cheating-exploding-covid-era

BBC News. (2006). Student cheats contract out work. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/education/5071886.stm

Blackburn, J. (2019). A question of trust? Educators’ views of contract cheating. Paper presented at the Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity. https://www.slideshare.net/JamesBlackburn7/a-question-of-trust-educators-views-of-contract-cheating

Bretag, T. (Ed.). (2016). Handbook of academic integrity. Springer.

Bretag, T. (2019). Contract cheating research: Implications for Canadian universities. Keynote presented at the Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110279

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., East, J., Green, M., & James, C. (2011). Academic integrity standards: A preliminary analysis of the Academic integrity policies at Australian Universities. Paper presented at the Proceedings of AuQF 2011 Demonstrating Quality.

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., Wallace, M., Walker, R., James, C., Green, M., Partridge, L. (2011). Core elements of exemplary academic integrity policy in Australian higher education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 7(2), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.21913/IJEI.v7i2.759

Buchwald, A. (1972, February 24). Art Buchwald—Commentary. Calgary Herald, p. 31. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Calgary Herald.

Buerger, G. E. (2002). The owl and the plagiarist: Academic misrepresentation in contemporary education. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Dalhousie University. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Canadian Consortium—International Center for Academic Integrity. (2018a). Agenda. Retrieved from https://live-academicintegrity.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FINAL-Cdn-Consortium-Day-Agenda-2018.pdf

Canadian Consortium—International Center for Academic Integrity. (2018b). Contract cheating facilitated discussion: Sarah Eaton. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://live-academicintegrity.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Contract-Cheating-facilitated-discussion-Sarah-Eaton-March-1-2018.pdf

Canadian Press. (1999, December 10). Cheaters are going high-tech. Calgary Herald. A3. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Calgary Herald.

Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity: Program and Abstracts. (2019). In S. E. Eaton J. Lock & M. Schroeder (Eds.). University of Calgary. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110293

Chang, D. H. (2018). Academic dishonesty in a post-secondary multilingual institution. BC TEAL Journal, 3(1), 49–62. https://ojs-o.library.ubc.ca/index.php/BCTJ/article/view/287

Clarke, R., & Lancaster, T. (2006, June19–21). Eliminating the successor to plagiarism: Identifying the usage of contract cheating sites. In Second International Plagiarism Conference. The Sage Gateshead, Tyne & Wear.

Couple charged in essay scam. (1989, May 30). The Ottawa Citizen, G15. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Ottawa Citizen.

Cribb, R. (1999, April 10). Term-paper mills thrive on Internet: Thousands of students mine 100 sites for cribbed essays to get out of academic work. Toronto Star, p. 1. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Toronto Star.

Christensen Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006a). Academic misconduct within higher education in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(2), 1–21. http://journals.sfu.ca/cjhe/index.php/cjhe/article/view/183537/183482

Christensen Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006b). Understanding academic misconduct. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(1), 49–63. https://journals.sfu.ca/cjhe/index.php/cjhe/article/view/183525

Curtis, G. J., & Clare, J. (2017). How prevalent is contract cheating and to what extent are students repeat offenders? Journal of Academic Ethics, 15(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-017-9278-x

Dallos, R. (1972, February 14). Ghost-writing papers a lucrative business: A pass—but don’t get caught. Calgary Herald, p. 51. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Calgary Herald.

Eaton, S. E. (2018). Contract cheating: A Canadian perspective. http://blogs.biomedcentral.com/bmcblog/2018/07/24/contract-cheating-a-canadian-perspective/

Eaton, S. E. (2019a). Contract cheating in Canada: National policy analysis. https://osf.io/n9kwt/

Eaton, S. E. (2019b). Reflections on the 2019 Canadian symposium on academic integrity. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 2(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v2i2.69454

Eaton, S. E. (2019c). U have integrity: Educator resource—How to lead a discovery interview about contract cheating. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111077

Eaton, S. E., & Dressler, R. (2019). Multilingual essay mills: Implications for second language teaching and learning. Notos, 14(2), 4–14. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110695

Eaton, S. E. (2020a). 15 Strategies to detect contract cheating. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112660

Eaton, S. E. (2020b). Academic integrity during COVID-19: Reflections from the University of Calgary. International Studies in Educational Administration, 48(1), 80–85. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/handle/1880/112293

Eaton, S. E. (2020c). An Inquiry into Major Academic Integrity Violations in Canada: 2010–2019. University of Calgary. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111483

Eaton, S. E. (2020d). Academic Integrity Policy Development and Revision: A Canadian Perspective (Guest lecture). Paper presented at the Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, YİDE6051—Academic Integrity Policies, PhD course. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112907

Eaton, S. E. (2021, June 1). Academic Integrity in Canadian Higher Education: The Impact of COVID-19 and a Call to Action. Paper presented at the Canadian Society for the Study of Higher Education (CSSHE), University of Alberta [online]. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113463

Eaton, S. E., Boisvert, S., Hamilton, M. J., Kier, C. A., Teymouri, N., & Toye, M. A. (2020a). Alberta Council on Academic Integrity (ACAI) 2019–2020 Annual Report. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112970

Eaton, S. E., & Edino, R. I. (2018). Strengthening the research agenda of educational integrity in Canada: A review of the research literature and call to action. International Journal of Educational Integrity, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0028-7

Eaton, S. E., Stoesz, B., Thacker, E., & Miron, J. B. (2020b). Methodological decisions in undertaking academic integrity policy analysis: Considerations for future research. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 3(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v3i1.69768

Eaton, S. E., & Turner, K. L. (2020). Exploring academic integrity and mental health during COVID-19: Rapid review. Journal of Contemporary Education Theory & Research, 4(2), 34–41. https://www.jcetr.gr/index.php/1308-2/

Ellingson, C. (2003, March 25). Teachers wage war against cyber-cheats: Schools deal with essays for sale on the Net. Prince Albert Daily Herald, p. 5. Retrieved from Canadian Newstream database.

Flostrand, A. (2018). Undergraduate student perceptions of academic misconduct in the business classroom. Simon Fraser University. https://www.sfu.ca/content/dam/sfu/tlgrants/documents/G0255_Flostrand_FinalReport.pdf

Goodman, E. (1971a, March 20). Term papers: Big business in Boston. The Boston Globe, pp. 1, 10. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe.

Goodman, E. (1971b, March 27). Term papers still hot item. The Boston Globe, pp. 1, 7. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe.

Goodman, E. (1971c, December 16). Term paper market flourishing. The Boston Globe, p. 47. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe.

Gray, B. C. (2022). Ethics, ed tech, and the rise of contract cheating. In S. E. Eaton & J. Christensen Hughes (Eds.), Academic integrity in Canada: An enduring and essential challenge: Springer.

Gray, J. M. (2002, March 27). What’s so creative about originality? The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from Canadian Newsstream database.

Grigg, G. A. (2010). Plagiarism in higher education: Confronting the policy dilemma. (Doctor of Philosophy). University of Melbourne.

Grue, D., Eaton, S. E., & Boisvert, S. (2021). Parallels between the contract cheating industry and organized crime. Alberta Council on Academic Integrity: Contract Cheating Working Group. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113323

Hechinger, F. M. (1972, March 19). Passing grades for a price. New York Times, p. E11. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: New York Times.

Hersey, C. (2019). “The struggle is real!” #Ineedapaperfast. Paper presented at the Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity.

Hersey, C., & Lancaster, T. (2015). The Online Industry of Paper Mills, Contract Cheating Services, and Auction Sites. Paper presented at the Clute Institute International Education Conference. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280830577_The_Online_Industry_of_Paper_Mills_Contract_Cheating_Services_and_Auction_Sites

International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE). (2020). Toolkit to support quality assurance agencies to address academic integrity and contract cheating. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/latest-news/publications/toolkit-support-quality-assurance-agencies-address-academic-integrity

Lancaster, T. (2019). Social media enabled contract cheating. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 2(2), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v2i2.68053

Lancaster, T., & Clarke, R. (2007). Assessing contract cheating through auction sites: A computing perspective. HE Academy for Information and Computer Sciences, 1–6. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.453.8656&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Lancaster, T., & Clarke, R. (2009, June 4). Contract cheating in UK Higher Education: Promoting a proactive approach. ASKe Institutional Policies and Procedures for Managing Student Plagiarism Event, Oxford Brookes University. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/26594434/Contract_Cheating_in_UK_Higher_Education_promoting_a_proactive_approach

Lee, M.-J. (2012). Essays for sale: CTV hidden camera investigation. CTV News Vancouver. https://bc.ctvnews.ca/essays-for-sale-ctv-hidden-camera-investigation-1.952016

Legislative Assembly of Ontario. (1972, June 14). Official report of debates (Hansard). Ghost-written term papers and examinations, Vol. 4, p. 3651. https://archive.org/details/v4hansard1972ontauoft/page/3650/mode/2up

Mah, B. (1999, October 22). Professors on lookout for cyber-cheaters. Calgary Herald, p. 124. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Calgary Herald.

Maeroff, G. I. (1971, July 10). Market in term papers is booming. New York Times, pp. 25, 27. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: New York Times.

Maich, S. (2006). Pornography, gambling, lies, theft and terrorism: The Internet sucks (Where did we go wrong?). MacLean’s, 119(43), 44–49.

McKenzie, A., Miron, J. B., & Ridgley, A. (2020a). Building a regional academic integrity network: Profiling the growth and action of the academic integrity council of Ontario. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v3i1.69836

McKenzie, A., Miron, J. B., Devereaux, L., Eaton, S. E., Persaud, N., Rowbotham, K., Steeves, M., Stoesz, B., & Thacker, E. (2020b). Contract cheating language within academic integrity policies in the university sector in Ontario, Canada. Paper presented at the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) 2020 Conference.

Miron, J. B. (2020). International Day of Action (IDoA) Against Contract Cheating 2020—Update from the chair of the IDoA planning committee. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v3i2.71473

Miron, J. B., & Ridgley, A. (2018). Contract cheating. Paper presented at the Canadian Consortium—International Center for Academic Integrity. https://live-academicintegrity.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/March-1-Contract-Cheating-by-Jennie-Miron.pdf

Miron, J. B. & McKenzie, A. (2020). Academic Integrity Council of Ontario (AICO): Avoiding contract cheating student tip sheet. https://academicintegritycouncilofontario.files.wordpress.com/2020/10/student-tip-sheet-avoiding-contract-cheating-1.pdf

Mourelatos, E. (2020). The Birth of an Idea: The IDoA and Its early growth. https://www.academicintegrity.org/blog/spotlight/thethe-birth-of-an-idea-the-idoa-and-its-early-growth/

Newton, P. (2018). How common is commercial contract cheating in higher education? Frontiers in Education, 3(67), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00067

Newton, P. M., & Lang, C. (2016). Custom essay writers, freelancers, and other paid third parties. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 249–271). Singapore, Springer.

O’Toole, L. (1974, September 19). The essay game. The Globe and Mail, p. 45. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Globe and Mail.

Oliphant, T. (2002). Cyber-plagiarism: Plagiarism in a digital world. Feliciter, 48(2), 78.

Parliament of Australia. (2020). Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency Amendment (Prohibiting Academic Cheating Services) Bill 2019. Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/bd1920a/20bd084

Pearson, C. (2002, October 26). Cyber cheats face U of W crackdown; Prosecutions on rise. The Windsor Star, A5. Retrieved from Canadian Newsstream database.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (UK) (QAA). (2020). Contracting to cheat in higher education: How to address essay mills and contract cheating (2nd. ed.). Retrieved from https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/guidance/contracting-to-cheat-in-higher-education-2nd-edition.pdf

Ridgley, A., Miron, J. B., & McKenzie, A. (2019). Building a regional academic integrity network: Profiling the growth and action of the Academic Integrity Council of Ontario. Paper presented at the Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110308

Rogerson, A. M., & Basanta, G. (2016). Peer-to-peer file sharing and academic integrity in the Internet age. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of Academic Integrity (pp. 273–285). Springer.

Roy, A. (1972). Bill 174: An act respecting ghost written term papers and examinations. In Legislative Assembly of Ontario: First and Second Sessions of the Twenty-Ninth Parliament. https://archive.org/details/v5ontariobills1972ontauoft/page/n193/mode/2up

RTNDA Canada announces 2006 Prairie Regional Award Recipients. (2007, May 12). Radio-Television News Directors Association (RNDA) Canada. http://rtndacanada.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=18637&item=30340

Schmidt, S. (1998, June 22). Wired world gives cheating a new face. Globe and Mail, p. C8.

Screening out the cheat. (1972, April 22). The Globe and Mail, p. 6. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Globe and Mail.

Seeland, J., Stoesz, B. M., & Vogt, L. (2020a). Preventing online shopping for completed assessments: Protecting students by blocking access to contract cheating websites on institutional networks. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v3i1.70256

Seeland, J., Stoesz, B., & Vogt, L. (2020b). Shopping interrupted: Blocking access to contract cheating. https://www.academicintegrity.org/blog/research/shopping-interrupted-blocking-access-to-contract-cheating/

Shepard, L. R. (1972, February 12). War on term-paper racket. The Christian Science Monitor, pp. 1, 2. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Christian Science Monitor.

Shepherd, J. (1973). Who’s the writer and who’s the ghost? Cosmopolitan, 174(3), 172–173, 186–187, 239, 241.

Statistics Canada. (1977). Canada Year Book 1976–1977. Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2021, January 2). Table 37–10–0011–01 Postsecondary enrolments, by field of study, registration status, program type, credential type and gender. Retrieved January 5, 2021, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710001101. https://doi.org/10.25318/3710001101-eng

Stead, S. (1978, March 10). How’s essay business? Dying at $5 a page. The Globe and Mail (1936–2017), p. 4. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Globe and Mail.

Steffenhagen, J. (2001, October 17). Plagiarism detector to screen UBC essays: University subscribes to web service aimed at discouraging wrongful online borrowing of passages or entire assignments: [Final Edition]. The Vancouver Sun, B3. Retrieved from Canadian Newsstream database.

Stewart, W. (1974). How the cost of food split up one family. MacLean’s. https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1974/4/1/how-the-cost-of-food-split-up-one-family

Stoesz, B., & Los, R. (2019). Evaluation of a tutorial designed to promote academic integrity. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 2(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v2i1.61826

Stoesz, B. M., Eaton, S. E., Miron, J. B., Thacker, E. (2019a). Academic integrity and contract cheating policy analysis of colleges in Ontario Canada. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 15(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-019-0042-4

Stoesz, B. M., Seeland, J., Vogt, L., Markovics, L., Denham, T., Gervais, L., & Usick, B. L. (2020b). Creating a collaborative network to promote cultures of academic integrity in Manitoba’s Post-Secondary Institutions. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v3i1.69763

Stoesz, B. M., Usick, B., & Eaton, S. E. (2019c). Outsourcing assessments: The implications of contract cheating for teaching and learning in Canada. Paper presented at the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (STLHE). http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110489

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. (TESQA). (2015). Report on student academic integrity and allegations of contract cheating by university students. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED564140.pdf

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. (TEQSA). (2017). Good practice note: Addressing contract cheating to safeguard academic integrity. Retrieved from https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/g/files/net2046/f/good-practice-note-addressing-contract-cheating.pdf?v=1507082628

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. (TEQSA). (2020). Contract cheating and blackmail. Retrieved from https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/contract-cheating-blackmail.pdf?v=1591659442

Thacker, E., Eaton, S. E., Stoesz, B., & Miron, J. B. (2019a). A deep dive into Canadian college policy: Findings from a provincial academic integrity and contract cheating policy analysis (updated). Paper presented at the Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity.

Thacker, E., Miron, J. B., Eaton, S. E., & Stoesz, B. (2019b). A deep dive into Canadian college policy: Findings from a provincial academic integrity and contract cheating policy analysis. Paper presented at the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) Annual Conference.

Thacker, E., Clark, A., & Ridgley, A. (2020). Applying a holistic approach to contract cheating: A Canadian response. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity. https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v3i1.69811

University of Calgary. (2019). Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity: Program and abstracts. In S. E. Eaton J. Lock & M. Schroeder (Eds.), University of Calgary. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110293

Usick, B. L., Miron, J. B., & Stoesz, B. M. (2020). Further Contemplations: Inaugural Canadian Symposium on Academic Integrity. Canadian Perspectives on Academic Integrity, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.11575/cpai.v3i1.70480

Waggoner, W. H. (1972). State acts to outlaw companies selling theses. The New York Times, p. 46. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times.

Walker, W. (2001, September 3). Teachers fight back against ‘rampant’ cyber-cheating; Web site lets schools check term papers for copied content. Toronto Star, A07. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Toronto Star.

Witherspoon, A. (1995). This pen for hire: On grinding out papers for college students. Harper’s Magazine, 290(June), 49–57.

Would have to keep records: A bill to stop essay sellers. (1972, June 16). Globe and Mail, p. 5. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Globe and Mail.

Wright, C. (1974, March 23). Difficult to fulfil demand: Essay-selling business booming. Globe and Mail, p. 5. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Globe and Mail.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr. Kim Clarke and Dr. Jonnette Watson Hamilton, from the Faculty of Law at the University of Calgary. They provided guidance on how to follow up on legal and legislative matters reported by the Canadian media. I further acknowledge Anna White, law student at the University of Calgary conducted some preliminary legal research and Serge Paquet, Reference Archivist, from the Archives of Ontario.

I extend special thanks to Dr. Geoffrey Buerger, whose doctoral thesis was particularly helpful to provide historical context. Dr. Buerger took the time to meet with me to share further details of his research via a video conference call as I was researching this chapter.

Finally, I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Ms. Kate Laukys, Index and Reference Officer of the House Publications and Language Services branch of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. She located and sent me links to the original legislative documents for the proposed bill brought forward 1972 archived online, which I would never have found otherwise.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Eaton, S. (2022). Contract Cheating in Canada: A Comprehensive Overview. In: Eaton, S.E., Christensen Hughes, J. (eds) Academic Integrity in Canada. Ethics and Integrity in Educational Contexts, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-83254-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-83255-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)