Abstract

Post-birth career breaks and their impact on mothers’ labor market outcomes have received considerable attention in the literature. However, existing evidence comes mostly from Western Europe and the US, where career breaks tend to be short. In contrast, Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, where post-birth career interruptions by mothers are typically much longer, have rarely been studied. In the first part of this study, we place CEE countries into the EU context by providing key empirical facts related to the labor market outcomes of mothers and the most important factors that may affect them. Besides substantial differences between CEE countries and the rest of the EU, there is also large heterogeneity within CEE itself, which we explore next. In the second part, we review the main family leave and formal childcare policies and reforms that have occurred in CEE countries since the end of Communism and provide a comprehensive survey of the existing scientific evidence of their impact on maternal employment. While research on the causal impacts of these policies is scarce, several important studies have recently been published in high-impact journals. We are the first to provide an overview of these causal studies from CEE countries, which offer an insightful extension to the existing knowledge from Western Europe and the US.

We thank the Czech Science Foundation, grant number 18-16667S, for financial support. We are grateful to the anonymous referee and Daniel Münich for their comments and suggestions. Anna Donina and Maksim Smirnov provided excellent research assistance. This text was previously circulated in a working paper format as Bičáková & Kalíšková (2021)

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

The EU definition of the employment impact of parenthood is slightly different, as it compares individuals with and without children below 6 (see EU social indicators’ definitions: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=818&langId=en&id=176). Including women with children older than 6 in the comparison group (following the Eurostat definition) could underestimate the employment impact of motherhood, as child-birth related career breaks of several years in some of the CEE countries are likely to have a long-term impact on maternal employment even beyond a child’s sixth birthday. Nevertheless, the employment impacts of motherhood are quite similar when comparing our and the Eurostat definition.

- 2.

- 3.

In most countries, the length of paid family leave is a combination of the length of maternity leave and the length of paid parental leave available to mothers.

- 4.

In accordance with the formal EU naming convention, we sometimes refer to the Czech Republic as Czechia. The two names are officially interchangeable.

- 5.

Note that there were also substantial differences among CEE countries in terms of ownership structure: In countries like Czechoslovakia and East Germany, almost all enterprises were state-owned, whereas in Poland and Hungary, the privatization process started as early as the 1980s, with a non-negligible share of the private sector comprised of small businesses and entrepreneurs (EBRD, 1995).

- 6.

There was a large expansion of nurseries and kindergartens in the 1970s and 1980s in CEE countries, which resulted in high levels of attendance of pre-school children before 1990. This contrasted with most OECD countries where these levels were still relatively low. In 1989, four in five pre-school children were enrolled in kindergartens in Central Europe. The quality of public childcare, however, varied substantially (UNICEF, 1999). Priority was given to families in which both parents worked so as to encourage female employment (Kocourková, 2002).

- 7.

Source: UNECE, https://w3.unece.org/PXWeb2015/pxweb/en/STAT/STAT__30-GE__03-WorkAndeconomy/001_en_GEWELabourActivity_r.px/table/tableViewLayout1/ We often use EU15 as a comparison group to CEE countries, because EU15 offers a clearly defined group of EU countries without the Communist past.

- 8.

Source: UNECE, https://w3.unece.org/PXWeb2015/pxweb/en/STAT/STAT__30-GE__03-WorkAndeconomy/001_en_GEWELabourActivity_r.px/table/tableViewLayout1/

- 9.

Starting one’s own business, travelling or studying abroad in non-Communist countries would be among the most popular activities that were not possible during Communism.

- 10.

In many CEE countries, this process of re-familization of family policies, which included extending paid parental leaves and cuts in nursery school places, started in the 1980s and intensified during the transition period (see Sect. 8.5.1 and Table 8.7 for an overview of changes in the duration of paid parental leave in CEE countries).

- 11.

Evidence of the impact of family leave policies on fertility in CEE countries is mixed. While Hiriscau (2020) shows that extending maternity leave increases fertility in Romania, Šťastná et al. (2020) argue that longer leaves lead to a longer interval between the first and second child, and lower probability of having two children within 10 years of the first birth in Czechia.

- 12.

Source: OECD (https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=LFS_SEXAGE_I_R)

- 13.

The long career breaks of highly educated women also represent a non-negligible cost to the economy by, e.g., lowering returns to women’s human capital investments.

- 14.

Unfortunately, data on the length of paid family leaves available to mothers and fathers are not available for all CEE countries. The discussion here is thus limited only to the countries with non-missing information. However, in Sect. 8.4.2, we compare family leave policies in all CEE EU member states. As we focus on maternal employment in 2019 (the most recent data available), we report the family leave policies as of 2016. The 3-year long family leaves would have still been ongoing or just completed, which is more relevant for the maternal employment in 2019 than any of the more recent policy changes (which we discuss later in Sect. 8.5.1).

- 15.

We attribute the high female participation rates to the still-prevailing norm of the working woman inherited from Communism and the fact that the majority of mothers return to the labor market even after taking long leaves.

- 16.

For EU15 countries, the coefficient from a simple regression of fertility on maternal employment is 19.37 with a p-value = 0.104. For CEE countries, the corresponding coefficient is −1.81 with p-value = 0.959.

- 17.

Employment impact of motherhood is calculated as the difference between the employment rate of childless women and women with at least one child below 6 years of age (in percentage points), see Sect. 8.2.

- 18.

The coefficient from a simple regression of the employment impact of motherhood on the duration of paid family leave is 0.2286 with p-value = 0.000.

- 19.

We report family leave policies as of 2016, given data constraints (regarding job protection) as well as relevance. As we focus on maternal employment (of women with children 0–6) in 2019 (the available most recent values), we consider the 2016 family leave policies the most relevant because the impact of paid family leaves of several years and long job protection duration are still likely to be reflected in the observed cross-country differences in the 2019 maternal employment.

- 20.

For example, the Czech parental leave system allows parents to choose from various lengths of benefit collection and the corresponding size of the monthly benefit. In 2016, Czech women were all eligible for the same total amount of parental leave allowance. They could, however, choose the period over which it will be paid. In particular, they could choose between 2 and 4 year-long duration of parental allowance receipt, with the corresponding level of monthly allowance between CZK 11,500 (for the 2-year track) and 4400 (for the 4-year track). Note, however, that only women with earnings above 77% of the median female wage were eligible for the 2-year track and women who did not work prior to childbirth were only eligible for the longest track of 4 years.

- 21.

The data only distinguish between the use of childcare of less or more than 30 h per week. As we want to filter out any occasional childcare of several hours per week that mothers may report but that would not enable them to work even part-time, we look at childcare usage greater than 30 h per week. Admittedly, the use of less than 30 h of childcare per week may still allow mothers to hold a part time job, which is why we also show the overall use of childcare of any duration in Table A.1 in the Appendix. We consider the cross-country differences in the use of less than 30 h of childcare per week (i.e. the differences between the values in Table A.1 and Table 8.5) when we discuss the variation in the prevalence of part-time jobs in Sect. 8.4.4.

- 22.

As discussed in Sect. 8.4.4, the use of part-time employment in Romania by mothers of young children is, however, limited, suggesting that the part-time use of formal childcare seems not to be driven by the demand of mothers with only partial employment.

- 23.

Admittedly, the amount of public expenditures on childcare may reflect (not only childcare availability and affordability) but also quality. Unfortunately, there is no measurable and comparable information about childcare quality either, so we have to abstract from the quality differences.

- 24.

We have also considered other flexible forms of work, such as work-from-home and self-employment. As these factors proved to have only very limited explanatory power for the observed differences in maternal employment, we do not cover them here but refer the reader to Bičáková and Kalíšková (2021), the working paper version of this chapter, where we also discuss the cross-country variation in the use of work from home and self-employment among women in CEE countries.

- 25.

- 26.

The comparison of findings from CEE countries with evidence from Western Europe, US, or Canada is complicated by the fact that the length of post-birth career breaks tends to be much longer in CEE countries (see Sect. 8.3.2).

- 27.

The factors that induced these policy changes and their motivation were discussed in Sect. 8.3.2.

- 28.

- 29.

Interestingly, after this substantial reduction in paid leave in 2004, the leave was extended again to 1.5 years in 2008.

- 30.

In Romania, the flexible program was abolished five years later in 2016. Czechia and Lithuania kept these programs.

- 31.

Nevertheless, there is some evidence from Denmark that women change occupations after childbirth, often reallocating from the private sector to the family-friendly public sector (Pertold-Gebicka et al. 2016).

- 32.

Some countries even sought to introduce cuts to benefits during the 1990s. Hungary introduced means-testing for the previously universal parental leave benefit (GYES) and phased out the insurance-based GYED in 1995. However, these changes were reversed three years later in 1998.

- 33.

Hungary first abolished the restriction on paid work for parents collecting parental leave benefits in 2005, but this was reversed in 2010 when a working hours limit of 30 h per week was introduced. Since 2014, there has been no further restriction on working hours for parents of children after their first birthday.

- 34.

While Saxonberg (2013) focuses specifically on the impact of parental leave and childcare policies on gender role division in the families (genderization and degenderization), their approach fits the classification that we are interested in as well, as policies that promote more equal participation of both parents in care-giving promotes mothers’ employment, whereas policies that are based on explicit or implicit assumption that mothers are the primary care-givers have detrimental impact on mothers’ employment.

- 35.

Saxonberg (2013) has only 4 CEE countries (Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland) in their sample. Apart from CEE countries, they cover 14 Western European countries, Australia, and the US. Based on our own data on parental leave policies (length, generosity, fathers’ incentives) and childcare (public spending on early childhood education and care, use of formal childcare) – see Tables 8.3, 8.4, and 8.5 above and the sources below Table 8.11 – we classify CEE countries into the categories described above. Note that we also update Saxonberg’s classification for Poland, as the parental leave system has changed there since 2013 and we consider the policies as of 2016.

- 36.

Examples of such countries in Saxonberg (2013) are the UK and the US.

- 37.

With a 78% prime-age female employment rate and 61% maternal employment rate.

- 38.

There is also some evidence that the low official female employment rates may mask the fact that some women work in the informal sector (Cousins, 2000).

- 39.

In contrast with Lalive et al. (2014), the only other study that explores the impact offamily leaves on maternal unemployment, who conclude that longer leaves in Austria lead to less unemployment in the first 3 years of the child.

- 40.

- 41.

For example: Coding for the question “the most important role of a woman is to take care of her home and family” is: 1 = totally agree, 2 = tend to agree, 3 = it depends, 4 = tend to disagree, 5 = totally disagree. While coding for the question “Do you approve or disapprove of a man taking parental leave to take care of his children?” is: 1 = strongly disapprove, 2 = tend to disapprove, 3 = neither approve nor disapprove, 4 = tend to approve, 5 = strongly approve.

- 42.

An average index of 3 implies a country with a balance of conservative and liberal answers, while an average index of 3.5 a country that is more liberal.

References

Adsera, A. (2004). Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labor market institutions. Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 17–43.

Ainsaar, M. (2001). The development of children and family policy in Estonia from 1945 to 2000 (pp. 23–40). Yearbook of Population Research in Finland.

Akgündüz, Y. E., van Huizen, T., & Plantenga, J. (2020). “Who’ll take the chair?” Maternal employment effects of a Polish (pre)school reform. Empirical Economics, 27.

Bargu, A., & Morgandi, M. (2018). Can mothers afford to work in Poland: Labor supply incentives of social benefits and childcare costs. In World Bank policy research working paper (No. 8295; Policy Research Working Paper). World Bank.

Bauernschuster, S., & Schlotter, M. (2015). Public child care and mothers’ labor supply—Evidence from two quasi-experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 123, 1–16.

Benati, L. (2001). Some empirical evidence on the ‘discouraged worker’ effect. Economics Letters, 70(3), 387–395.

Bettendorf, L. J. H., Jongen, E. L. W., & Muller, P. (2015). Childcare subsidies and labour supply – Evidence from a large Dutch reform. Labour Economics, 36, 112–123.

Bičáková, A. (2016). Gender unemployment gaps in the EU: blame the family. IZA Journal of Labor Studies, 5, 22.

Bičáková, A., & Kalíšková, K. (2019). (Un)intended effects of parental leave policies: Evidence from the Czech Republic. Labour Economics, 61(101783).

Bičáková, A., & Kalíšková, K. (2021). Career-breaks and maternal employment in CEE countries., CERGE-EI WP No.706

Blanden, J., Del Bono, E., McNally, S., & Rabe, B. (2016). Universal pre-school education: the case of public funding with private provision. Economic Journal, 126(592), 682–723.

Blau, D., & Robins, L. (1988). Child care cost and family labour supply. Review of Economics and Statistics., 70, 374–381.

Brazienė, R., & Vyšniauskienė, S. (2021). Paid leave policies and parental leave choices in Lithuania. Tiltai, 85(2), 28–45.

Cascio, E., & Schanzenbach, D. W. (2013). The impacts of expanding access to high-quality pre-school education. NBER Working Paper No. 19735.

Cipollone, A., Patacchini, E., & Vallanti, G. (2014). Female labour market participation in Europe: Novel evidence on trends and shaping factors. IZA Journal of European Labor Studies, 3(1), 18.

Cleveland, G., Gunderson, M., & Hyatt, D. (1996). Child care costs and the employment decision of women: Canadian evidence. Canadian Journal of Economics, 29, 132–151.

Connelly, R. (1992). The effect of child care costs on married women’s labour force participation. Review of Economics and Statistics., 74, 83–90.

Cousins, C. (2000). Women and employment in Southern Europe: The implications of recent policy and labour market directions. South European Society and Politics, 5(1), 97–122.

Cukrowska-Torzewska, E., & Lovasz, A. (2016). Are children driving the gender wage gap? Comparative evidence from Poland and Hungary. Economics of Transition, 24(2), 259–297.

Dahl, G. B., Løken, K. V., Mogstad, M., & Salvanes, K. V. (2016). What is the case for paid maternity leave? Review of Economics and Statistics, 98(4), 655–670.

Dobrotić, I. (2018). Ambivalent character of leave policies development in Croatia: Between pronatalist and gender equality agenda. Revista Del Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social Economia y Sociologia, 136, 107–126.

Dobrotić, I., & Stropnik, N. (2020). Gender equality and parenting-related leaves in 21 former socialist countries. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 40(5/6), 495–514.

Dohotariu, A. (2018). Parental leave provision in Romania between inherited tendencies and legislative adjustments. Symposion, 5(1), 41–57.

EBRD. (1995). Transition report 1995. European Bank for Recinstruction and Development. https://www.ebrd.com/publications/transition-report-archive

Fratczak, E., Kulik, M., & Malinowski, M. (2003). Legal regulations related to demographic events and processes: Selected legal regulations pertaining to children and family–social policy; Poland, Selected years 1950–2002, Vol. 7B Demographic analysis section, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock.

Gonul, F. (1992). New evidence on whether unemployment and out of the labor force are distinct states. The Journal of Human Resources, 27(2), 329–361.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2011). Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment. Journal of Public Economics, 95(11–12), 1455–1465.

Henderson, A., & White, L. A. (2004). Shrinking welfare states? Comparing maternity leave benefits and child care programs in European Union and North American welfare states, 1985–2000. Journal of European Public Policy, 11(3), 497–519.

Hiriscau, A. (2020). The effect of paid maternity leave on fertility and mother’s labor force participation. Unpublished manuscript. https://appam.confex.com/appam/2020/mediafile/ExtendedAbstract/Paper37470/Hiriscau_Maternity_Leave.pdf

ILO. (2014). Maternity and paternity at work: Law and practice across the world. International Labour Office.

Jones, S. R. G., & Riddell, W. C. (2006). Unemployment and Nonemployment: Heterogeneities in Labor Market States. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(2), 314–323.

Karu, M. (2012). Parental leave in Estonia: Does familization of fathers lead to defamilization of mothers? NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 20(2), 94–108.

Karu, M., & Pall, K. (2009). Estonia: Halfway from the Soviet Union to the Nordic countries. In S. B. Kamerman & P. Moss (Eds.), The politics of parental leave policies (pp. 69–85). The Policy Press.

Kazakova, Y. (2019). Childcare availability and maternal labour supply in Russia (ISER Working Paper Series 2019-11, Institute for Social and Economic Research).

Kocourková, J. (2002). Leave arrangements and childcare services in Central Europe: Policies and practices before and after the transition. Community, Work & Family, 5(3), 301–318.

Korintus, M., & Stropnik, N. (2009). Hungary and Slovenia: long leave or short? In The politics of parental leave policies: Children, parenting, gender and the labour market (pp. 135–159).

Kurowska, A. (2017). The impact of an unconditional parental benefit on employment of mothers: A comparative study of Estonia and Lithuania. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 37(1/2), 33–50.

Lalive, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2009). How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1363–1402.

Lalive, R., Schlosser, A., Steinhauer, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2014). Parental leave and mothers' careers: The relative importance of job protection and cash benefits. Review of Economic Studies, 81(1), 219–265.

Levin, V., Munoz Boudet, A. M., Rosen, B. Z., Aritomi, T., Flanagan, J., & Rodriguez-Chamussy, L. (2015). Why should we care about care?: The role of childcare and eldercare in former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. World Bank.

Lokshin, M. (2004). Household childcare choices and women’s work behavior in Russia. Journal of Human Resources, 39(4), 1094–1115.

Lokshin, M., & Fong, M. (2006). Women’s labour force participation and child care in Romania. Journal of Development Studies, 42(1), 90–109.

Lovász, A., & Szabó-Morvai, Á. (2017). Childcare and maternal labor supply – A cross-country analysis of quasi-experimental estimates from 7 countries. (BWP – 2017/3; Budapest Working Papers on the Labour Market).

Lovász, A., & Szabó-Morvai, Á. (2019). Childcare availability and maternal labor supply in a setting of high potential impact. Empirical Economics, 56(6), 2127–2165.

LP&R. (2010–2019). International network on leave policies and research. Available at: https://www.leavenetwork.org/leave-policies-research/

Lundin, D., Mörk, E., & Öckert, B. (2008). How far can reduced childcare prices push female labour supply? Labour Economics, 15(4), 647–659.

Magda, I., Kiełczewska, A., & Brandt, N. (2018). The effects of large universal child benefits on female labour supply. (IZA Discussion Paper, No. 11652).

Matysiak, A., & Szalma, I. (2014). Effects of parental leave policies on second birth risks and women’s employment entry. Population, 69(04), 599–636.

Morrissey, T. W. (2017). Child care and parent labor force participation: A review of the research literature. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(1), 1–24.

Mullerová, A. (2017). Family policy and maternal employment in the Czech transition: A natural experiment. Journal of Population Economics, 30(4), 1185–1210.

Nollenberger, N., & Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2015). Full-time universal childcare in a context of low maternal employment: Quasi-experimental evidence from Spain. Labour Economics, 36, 124–136.

Olivetti, C., & Petrongolo, B. (2017). The economic consequences of family policies: Lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 205–230.

Pertold-Gebicka, B. (2020). Parental leave length and mothers’ careers: What can be inferred from occupational allocation? Applied Economics, 52(9), 879–904.

Pertold-Gebicka, B., Pertold, F., & Datta Gupta, N. (2016). Employment adjustments around childbirth (IZA DP No. 9685). http://ftp.iza.org/dp9685.pdf

Rossin-Slater, M. (2017). Maternity and family leave policy. In S. L. Averett, L. M. Argys, & S. D. Hoffman (Eds.), Oxford handbook on the economics of women. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Saxonberg, S. (2013). From defamilialization to degenderization: Toward a new welfare typology 1. Social Policy & Administration, 47(1), 26–49.

Saxonberg, S., & Sirovátka, T. (2006). Failing family policy in post-communist Central Europe. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 8(2), 185–202.

Schönberg, U., & Ludsteck, J. (2014). Expansions in maternity leave coverage and mothers’ labor market outcomes after childbirth. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(3), 469–505.

Sobotka, T. (2003). Re-emerging diversity: Rapid fertility changes in Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse of the communist regimes. Population, 58(4), 451.

Spéder, Z., & Kamarás, F. (2008). Hungary: Secular fertility decline with distinct period fluctuations. In Frejka, T., Sobotka, T., Hoem, J. M., & Toulemon, L. (Eds.), Childbearing Trends and Policies in Europe, Demographic Research, 19(7), 599–664.

Šťastná, A., Kocourková, J., & Šprocha, B. (2020). Parental leave policies and second births: A comparison of Czechia and Slovakia. Population Research and Policy Review, 39(3), 415–437.

UNICEF. (1999). Women in transition (MONEE Project, Regional Monitoring Report 6). UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Waldfogel, J. (1999). The impact of the family and medical leave act. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 18(2), 281–302.

Zajkowska, O. (2019). Parental leaves in Poland: Goals, challenges, perspectives. Problemy Polityki Społecznej: Studia i Dyskusje, 46(3), 0–1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Employment rate of women with children below 6, 2019

Source: Eurostat/LFST_HHEREDCH – (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFST_HHEREDCH/)

Note: Prime-aged women are women from 25 to 54 years old

Employment and labor force participation rates of prime-age women, 2019

Source: Eurostat/LFST_HHEREDCH, LFSA_ARGAN – (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFST_HHEREDCH/; https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfsa_argan&lang=en)

Note: Prime-aged women are women from 25 to 54 years old

Employment and unemployment rates of prime-age women, 2019

Source: Eurostat/LFST_HHEREDCH, LFSA_URGAN – (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFST_HHEREDCH/; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFSA_URGAN__custom_1536662/default/table?lang=en)

Note: Prime-aged women are women from 25 to 54 years old

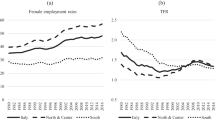

Evolution of labor force participation of women (older than 15) during the 1990–2019 period

Source: World Bank/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS), own calculations of the EU15 mean

Evolution of the fertility rate during the 1989–2019 period

Source: Eurostat/DEMO_FRATE (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DEMO_FRATE__custom_411366/)

Evolution of employment rate of prime-age mothers with young children during the 2005–2019 period

Source: Eurostat/LFST_HHEREDCH – (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFST_HHEREDCH/)

Note: Prime-aged women are women from 25 to 54 years old. Young children are children of age less than 6 years

8.1.1 Construction of the Gender-Role Index (GRI)

The data for the construction of the gender-role index (GRI) come from Special Eurobarometer 465: Gender Equality 2017, available at https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2154_87_4_465_eng?locale=en

Questions used in the Gender-role Index are:

-

1.

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: the most important role of a man is to earn money.

-

2.

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: the most important role of a woman is to take care of her home and family.

-

3.

Do you approve or disapprove of a man taking parental leave to take care of his children?

-

4.

Do you approve or disapprove of a man doing an equal share of household activities?

The responses to the questions 1 and 2 were:

-

Totally agree

-

Tend to agree

-

Tend to disagree

-

Totally disagree

The responses to the questions 3 and 4 were:

-

Strongly approve

-

Tend to approve

-

Neither approve nor disapprove

-

Tend to disapprove

-

Strongly disapprove

The answers coded as DK (do not know) where dropped. The other responses were coded by an integer number from 1 to 5 such that the most conservative answer is 1, while the most liberal answer is 5.Footnote 41 Then for each country and for each of questions 1, 2, 3, and 4, we sum the coded responses and divide over the total number of responses (excluding DK). We thus obtain the average of the coded responses for each country and for each of questions 1, 2, 3, and 4. Finally, we calculate unweighted averages of these average coded responses for each country.Footnote 42

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bičáková, A., Kalíšková, K. (2022). Career-Breaks and Maternal Employment in CEE Countries. In: Molina, J.A. (eds) Mothers in the Labor Market. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99780-9_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99780-9_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-99779-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-99780-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)