Abstract

This chapter recognises that current food consumption patterns, often characterised by higher levels of food waste and a transition in diets towards higher energy, more resource-intensive foods, need to be transformed. Food systems in both developed and developing countries are changing rapidly. Increasingly characterised by a high degree of vertical integration, evolutions in food systems are being driven by new technologies that are changing production processes, distribution systems, marketing strategies, and the food products that people eat. These changes offer the opportunity for system-wide change in the way in which production interacts with the environment, giving greater attention to the ecosystem services offered by the food sector. However, developments in food systems also pose new challenges and controversies. Food system changes have responded to shifts in consumer preferences towards larger shares of more animal-sourced and processed foods in diets, raising concerns regarding the calorific and nutritional content of many food items. By increasing food availability, lowering prices and increasing quality standards, they have also induced greater food waste at the consumer end. In addition, the potential fast transmission of food-borne disease, antimicrobial resistance and food-related health risks throughout the food chain has increased, and the ecological footprint of the global food system continues to grow in terms of energy, resource use, and impact on climate change. The negative consequences of food systems from a nutritional, environmental and livelihood perspective are increasingly being recognised by consumers in some regions. With growing consumer awareness, driven by concerns about the environmental and health impacts of investments and current supply chain technologies and practices, as well as by a desire among new generations of city dwellers to reconnect with their rural heritage and use their own behaviour to drive positive change, opportunities exist to define and establish added-value products that are capable of internalising social or environmental delivery within their price. These forces can be used to fundamentally reshape food systems by stimulating coordinated government action in changing the regulatory environment that, in turn, incentivises improved private sector investment decisions. Achieving healthy diets from sustainable food systems is complex and requires a multi-pronged approach. Actions necessary include awareness-raising, behaviour change interventions in food environments, food education, strengthened urban-rural linkages, improved product design, investments in food system innovations, public-private partnerships, public procurement, and separate collection that enables alternative uses of food waste, all of which can contribute to this transition. Local and national policy-makers and small- and large-scale private sector actors have a key role in both responding to and shaping the market opportunities created by changing consumer demands.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

There is global convergence on the need to transform food systems so that they deliver nourishment and health for humanity while contributing to reducing the environmental pressures on our ecosystems. Transforming food systems involves five action tracks: AT1) access to safe and nutritious food, AT2) sustainable consumption, AT3) nature-positive production, AT4) equitable livelihood, and AT5) resilience to shocks and stress. As discussed in Action Track 1, we are not on track to meet international targets related to healthy diets. Currently, 690 million people are chronically malnourished, and two billion individuals suffer micronutrient deficiencies. Over-consumption, notably of unhealthy dietary items, is rising rapidly. Two billion people are overweight or obese, with many suffering chronic diseases driven by poor dietary health (Development Initiatives, 2020; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2020). Food, which enjoys the most proximate relationship to our physical health, is failing us. Globally, poor-quality diets are linked to 11 million deaths per year (Afshin et al. 2019; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2020).

As discussed in Action Track 1, we are failing the planet by enabling the food system to be the single largest driver of multiple environmental pressures. Food production accounts for 80% of land conversion and biodiversity loss, including the collapse of major marine fisheries and freshwater ecosystems (Campbell et al. 2017; IPCC 2019) and high levels of contamination of freshwater and marine ecosystems (Mateo-Sagasta et al. 2017); it is responsible for 70% of freshwater withdrawals (Campbell et al. 2017), with major river systems such as the Colorado River in the USA no longer reaching their deltas; and it contributes approximately 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC 2019). Action Track 2 recognises that current food usage patterns, often characterised by high levels of food loss and waste, significant prevalence of the consumption of energy-rich diets, and the production of natural resource-intensive foods, need to be transformed in order to protect both people and the planet. At the same time, context is very important. The challenges and opportunities associated with a nutrient transition will vary for different contexts and countries and will need to be evaluated and solved with an array of different solutions appropriate to their local conditions, culture and values. Awareness-raising, regulatory and behaviour change interventions in food environments, food education, strengthened urban-rural linkages, reformulation, improved product design, packaging and portion sizing, investments in food system innovations, public-private partnerships, public procurement, and separate collection that enables the reutilisation of food waste can all contribute to this transition. Local and national policy-makers and private sector actors of all sizes have a key role in both responding to and shaping the market opportunities created by changing consumer demands.

2 Building the Evidence for Healthy Diets

A healthy diet is health-promoting and disease-preventing. It provides adequacy, without excess, of nutrients and health-promoting substances from nutritious foods and avoids the consumption of health-harming substances (Healthy diet: A definition for the United Nations Food Systems Summit 2021). It must supply adequate calories for energy balance and include a wide variety of high-quality and safe foods across a diversity of food groups to provide the various macronutrients, micronutrients and other food components needed to lead an active, healthy and enjoyable life.

Consumer demand, availability, affordability and accessibility are important drivers of dietary patterns. It is essential that these four aspects are considered simultaneously when pursuing dietary shifts (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2020). There is great diversity in the food and culinary traditions that, together, can form healthy diets, which vary widely across countries and cultures according to traditions, preferences and local food supplies. Food-based dietary guidelines translate these common principles into nationally or regionally relevant recommendations that consider these differences, as well as context-specific diet-related health challenges. National food-based dietary guidelines provide context-specific advice and principles on healthy diets and lifestyles, which are rooted in sound evidence and respond to a country’s public health and nutrition priorities, food production and consumption patterns, socio-cultural influences, food composition data, and accessibility, among other factors.Footnote 1 Most food-based dietary guidelines recommend consuming a wide variety of food groups and diverse foods within food groups, plentiful fruits and vegetables, the inclusion of starchy staples, animal-source foods and legumes, and the limiting of excessive fat, salt and sugars (Herforth et al. 2019; Springmann et al. 2020). However, there can be wide variation in inclusion of and recommendations for other foods. Only 17% of food-based dietary guidelines make specific recommendations about quantities of meat/egg/poultry/animal-sourced food to consume (20% make specific recommendations about fish), and only three countries (Finland, Sweden and Greece) make specific quantitative recommendations to limit red meat (Herforth et al. 2019). Only around one-quarter of food-based dietary guidelines recommend limiting consumption of ultra-processed foods, yet this is emerging as one of the most significant dietary challenges around the world.

Adherence with national food-based dietary guidelines and recommendations around the world is low. However, accurate data on actual consumption and its determinants is limiting, particularly for low- and low-middle-income countries (Lele et al. 2021). Recent estimates of consumption found that the foods available did not meet a single recommendation laid out in national food-based dietary guidelines in 28% of countries, and the vast majority of countries (88%) met no more than two out of twelve dietary recommendations (Springmann et al. 2020). Dietary intake surveys show vast regional and national differences in consumption of the major food groups (Afshin et al. 2019). No regions globally have an average intake of fruits, whole grains, or nuts and seeds in line with recommendations, and only central Asia meets the recommendations for vegetables. In contrast, the global average intake (and several regional averages) of red meat, processed meat and sugar-sweetened beverages exceeds recommended limits. Australasia and Latin America had the highest levels of red meat consumption, with high-income North America, high-income Asia Pacific and western Europe consuming the highest amount of processed meat (Afshin et al. 2019). In general, consumption of nutritious foods has been increasing over time, albeit, likewise, the consumption of foods high in fat, sugar, and salt, in a trend that is particularly evident as country incomes rise (Imamura et al. 2015). Of particular concern is the growing importance of highly processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages in diets across the world. Sales of highly processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages are about ten-fold higher in high-income compared to lower middle-income countries. However, sales growth is evident across all regions, the fastest occurring in middle-income countries (Baker et al. 2020).

Micronutrient dietary needs require consideration, especially for women of reproductive age, pregnant and lactating women, and children and adolescents. The odds of death in childbirth double with anaemia (Daru et al. 2018), a condition often caused by nutrient deficiency and affecting almost 470 million women of reproductive age and more than 1.6 billion people globally (WHO 2008). Iron deficiency is estimated to cause 591,000 perinatal deaths and 115,000 maternal deaths per year (Stoltzfus et al. 2004), whereas undernutrition is an underlying cause of 45% of all deaths of children under the age of 5.

Animal-sourced foods can provide high-quality amino acid profile and micronutrient bioavailability. A recent study showed improved linear growth in children receiving animal-sourced foods vs cereal-based diets or no intervention (Eaton et al. 2019). Daily egg provision to young children has also shown increased linear growth compared to control (Iannotti et al. 2017). These changes in growth can be equated to larger economic gains across nations, continents, and globally. A review of the association between stunting and adult economic potential found that a 1 cm increase in stature is associated with a 4% increase in wages for men and a 6% increase in wages for women (McGovern et al. 2017). The Cost of Hunger in Africa series has quantified the social and economic impact of hunger and malnutrition in 21 African countries and concluded that (a) 8–44% of all child mortality is associated with undernutrition, (b) between 1% and 18% of all school repetitions are associated with stunting, (c) stunted children achieve 0.2–3.6 years less in school education, (d) child mortality associated with undernutrition has reduced national workforces by 1–13.7%, and (e) 40–67% of the working age population suffered from stunting as children (The Cost of Hunger in Africa series | World Food Programme 2021). Furthermore, hunger and undernutrition have cost countries between 2% and 17% of their GDP (The Cost of Hunger in Africa series | World Food Programme 2021).

Fish and fish products can be a key component of a healthy diet, given their nutrient-dense profile, including protein, omega-3 fatty acid and other micronutrients. In addition to the underconsumption of fruits, whole grains, nuts and seeds, as noted earlier, seafood is also generally eaten below recommended intake levels. With the exception of high-income Asia Pacific, seafood omega-3 fatty acid consumption is lower than the optimal levels in all 21 global burden-of-disease regions. The recently-released 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans also notes that only 10% of Americans eat the recommended amount of seafood – two servings – each week.

3 Building the Evidence on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems

Foremost, we need evidence on actual food consumption to consider shifts to dietary patterns that promote all dimensions of individuals’ health and well-being; have low levels of environmental pressure and impact; are accessible, safe and equitable; and are culturally acceptable (FAO and WHO 2019). Considering current environmental challenges, transitioning to food systems that can enhance natural ecosystems, rather than simply sustaining them, may be desirable.

The conceptual transition from healthy diets to healthy diets from sustainable food systems has been mediated by recent studies linking food availability patterns, and projections, to non-communicable disease health consequences, and the environmental impacts of food production (Tilman and Clark 2014; Springmann et al. 2018a; Willett et al. 2019). A broad range of food availability patterns have been tested as alternatives to current patterns, including Mediterranean, vegetarian, vegan, pescatarian, low animal products and many other variants (Aleksandrowicz et al. 2016; IPCC 2019). The most recent set of studies is embodied in the work of the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems (Willett et al. 2019). Healthy diets, based on food groups, were designed from a large body of evidence from nutrition observational studies. This helped to establish ranges of inclusion of different types of foods. It is important to note that these dietary recommendations diverge from most food-based dietary guidelines, and often have lower ranges of inclusion of animal-sourced foods, which have been the topic of significant debate, and therefore not widely accepted. The authors then used six environmental dimensions of importance to planetary health and earth system processes (greenhouse gas emissions, cropland use, water use, nitrogen and phosphorus use and biodiversity), using the planetary boundaries concept (Rockström et al. 2009), as boundary conditions for achieving a healthy diet from a sustainable food system. The environmental limits of food described by the EAT-Lancet Commission define a safe environmental space for food to help guide sustainable food consumption patterns.

Willett et al. (2019) found that flexitarian diets that allow for diversity in consumption options, including moderate meat consumption, would significantly reduce environmental impacts compared to baseline scenarios reflecting current consumption patterns. Flexitarian diets include the following characteristics:

-

(a)

high in diverse plant-based foods.

-

(b)

high in the consumption of whole grains, legumes, nuts, vegetables and fruits.

-

(c)

low in the consumption of animal-sourced foods (but requiring increases in fish consumption).

-

(d)

low in fats, sugars and discretionary/ultra-processed foods.

These diets can avert 10.8–11.6 million deaths per year from non-communicable diseases, a reduction of 19–24% from the baseline (consistent with the Global Burden of Disease studies). From an environmental perspective, transitions towards flexitarian patterns could primarily contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as a reduction in animal-sourced foods also reduces land use and the numbers of animals utilised, along with their associated emissions. However, increases in fruits, nuts and vegetables require more land, water and fertilisers, and therefore increases in productivity of cereals and legumes to bridge yield gaps by close to 75%, and reductions in waste of 50% would be needed to achieve these diets within all sustainability constraints. These dynamics are consistent across many studies exploring dietary variants (Aleksandrowicz et al. 2016; Jarmul et al. 2020). However, the environmental footprint of foods is strongly dependent on where and how foods are produced, leaving significant room for innovation and improvement. Moreover, the adoption of any of the four alternative healthy diet patterns (flexitarian, pescatarian, vegetarian and vegan) could potentially contribute to significant reductions of the social cost of greenhouse gas emissions, ranging from USD 0.8 to 1.3 trillion (50–74%) (FAO et al. 2020).

However, a limitation of plant-based diets is that they may not fulfil micronutrient needs, especially of those most vulnerable, such as women of reproductive age, pregnant and lactating women, and children and adolescents. In contexts in which diverse options for fortified cereals, grains, and foods are abundant, these outcomes demonstrate great potential for improving health and environmental indices, because risk of undernutrition can be mitigated by the diversity of options in the food environment. In particular, biofortification of staple foods can lead to the higher accessibility of micronutrients, particularly for the poor and vulnerable. However, in contexts in which such diversity of high-quality, fortified products is not abundant, the health risk of anaemia and iron deficiency due to a lack of vitamins and minerals is significant (as outlined above). The recommendations to move to more plant-based diets are complicated by the high quality of animal-sourced foods in terms of their amino acid profile and micronutrient bioavailability and the evidence that the addition of such foods to plant-based diets of many populations could have large individual and societal benefits. Thus, when economic and socio-cultural sustainability are considered, as well as the complex landscape of diverse nutrition situations globally, healthy diets that take sustainability into consideration will look different in diverse contexts around the world.

Transitions towards healthy diets, let alone sustainable consumption, are critical contributors to achieving climate stability and halting the rampant loss of biodiversity. Combined actions on securing habitat for biodiversity, improving production practices, and encouraging better consumption would allow for halting biodiversity loss and bending the curve towards restoration by 2030 (Leclere et al. 2020).

There is also a financial case for shifting to healthy diets from sustainable food systems. There are hidden costs in our dietary patterns and the food systems supporting them, two of the most important of which are the health- and climate-related costs that the world incurs (FAO et al. 2020). If current food consumption trends continue, diet-related health costs linked to non-communicable diseases and their rates of mortality are projected to exceed USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2030. On the other hand, shifting to healthy diets that include sustainability considerations would lead to an estimated reduction of up to 97% in direct and indirect health costs. The diet-related social cost of greenhouse gas emissions associated with current dietary patterns is projected to exceed USD 1.7 trillion per year by 2030. The adoption of healthy diets that include sustainability considerations would reduce the social cost of greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 41–74% in 2030 (FAO et al. 2020).

Many studies (Springmann et al. 2018a; Swinburn et al. 2019; Willett et al. 2019; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2020; HLPE 2020) that discuss redirecting consumption recognise the need for different consumer behavioural shifts in different locations and contexts. For example, in low-income countries, achieving a healthy diet from sustainable food systems would require increasing the consumption of most nutrient-rich food groups, including animal-sourced foods, vegetables, pulses and fruits, while reducing some starches, oils and discretionary foods (Willett et al. 2019). In contrast, in many high-income countries, achieving the same balance would require reducing the consumption of animal-sourced foods, sugars and discretionary/processed foods, while still increasing the consumption of healthy plant-based ingredients. For many countries, the transition will be complex and the changes difficult to implement. The Global Nutrition Report 2020 demonstrated that, of the 143 countries with comparable data, 124 have double or triple the burden, meaning that micronutrient deficiency is still prevalent in many developed countries demonstrating high levels of overweight/obesity (Development Initiatives 2020). It would be required that these actions play out simultaneously in different population cohorts within these countries to achieve the desired benefits (Willett et al. 2019; Development Initiatives 2020; HLPE 2020), while a smaller number of countries (e.g., Japan) would have smaller adjustments to make.

A global shift towards healthy diets from sustainable food systems will require significant transformations in food systems, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution for countries. Assessing context-specific barriers, managing short-term and long-term trade-offs and exploiting synergies will be critical. In countries where the food system also drives the rural economy, care must be taken to mitigate the potential negative impacts on incomes and livelihoods as food systems transform to deliver affordable healthy diets (FAO et al. 2020). Artificial intelligence may be able to assist in the transition to healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Examples of its application are in the management and automation of crop and livestock production systems and the development of demand-driven supply chains. However, trade-offs and ethical considerations that arise from the use of artificial intelligence need to be carefully managed (Camaréna 2020).

Fish and fish products have one of the most eco-efficient production profiles of all animal proteins. Ocean animals are more efficient than terrestrial systems in producing protein; their impact on climate change and land use is, in general, much lower than that of terrestrial animal proteins. One vital way to improve consumption of nutrient-rich and sustainable seafood is through aquaculture, the world’s fastest growing food sector. According to the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2021), “Aquaculture has real potential to accelerate economic growth, provide employment opportunities, improve food security, and deliver an environmentally sustainable source of good nutrition for millions of people, especially in low- and middle-income countries”. The Ocean Panel also documented that the volume of food production from the ocean could be considerably increased. Under optimistic projections, the ocean could produce up to six times more food than it does today, and it could do so with a low environmental footprint.

4 Transitioning to Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems

The evidence is abundantly clear that, without shifts in consumption patterns towards health and sustainability, we will fail to achieve multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Climate Agreement, or the post-2020 biodiversity goals, and we will lose the opportunity to reposition food in such a way to improve health and regenerate the environment. Achieving these transitions and managing the trade-offs and synergies will require additional attention to many facets of food systems, including:

Food Environments

The consumption of healthy diets from sustainable food sources is dependent on sustainably produced healthy dietary items being available, affordable and accessible in different outlets. Whether they are in open markets in low- and middle-income countries, in supermarkets or in corner shops across the globe, or available through bartering and sharing, the provisioning of nutritious food at affordable prices is a critical element for achieving transitions towards sustainable consumption (Downs et al. 2009; Swinburn et al. 2019; FAO et al. 2020). These physical environments need to be developed so as to suit culture and tradition in different locations. Additionally, regulated advertisement and product placement will be essential for addressing positive behavioural changes (Swinburn et al. 2019). To increase consumption of healthy diets, the cost of nutritious foods must be affordable for all, although farmers must also be compensated for the real cost of growing food. The cost drivers of these diets can be found throughout the food supply chain, within the food environment, and in the political economy that shapes trade, public expenditure and investment policies (Swinburn et al. 2019; FAO et al. 2020).

Tackling these cost drivers will require large transformations in food systems at the producer, consumer, political economy, and food environment levels. Trade policies, mainly protectionary trade measures and input subsidy programmes, tend to protect and incentivise the domestic production of staple foods, such as rice and maize, often to the detriment of nutritious foods, like fruits and vegetables. International trade could certainly improve food system resilience by spreading the risk of disruption in supply where it is not fully reliant on domestic production and/or trading with neighbouring countries. However, substantial imports from climate-vulnerable countries by climate-resilient trade partners could lead to a number of interlinked problems, including a ‘nutrient drain’ of healthy dietary items away from production countries to countries with a much more diverse supply of foods, disrupting supply to importing countries when yields in production countries are affected by environmental influences (Scheelbeek et al. 2020). Non-tariff trade measures can help improve food safety, quality standards and the nutritional value of food, but they can also drive up the costs of trade, and hence food prices, negatively affecting the affordability of healthy diets (FAO et al. 2020). Nutrition-sensitive social protection policies, such as cash transfers, may assist the purchasing power and affordability of healthy diets of the most vulnerable populations.

Policies that more generally foster behavioural change towards healthy diets will also be needed. A critical challenge is the tremendous perishability of fruits and vegetables, particularly in tropical climates (Mason-D’Croz et al. 2019), where refrigeration, food processing and sustainable packaging may be critical contributions in creating environmental and public health value. In both urban and rural areas, the lack of physical access to food markets, especially to fresh fruit and vegetable markets, represents a formidable barrier to accessing a healthy diet, especially for the poor. Finally, empowering all people, and especially the poor and vulnerable, with sufficient physical and human capital resources, assets and incomes is the necessary precondition to improving access to healthy diets. This will enable the making of choices, regarding what to produce and consume, leaving no one hungry or malnourished, while allowing them to consume healthy and nutritious food and preserving ecosystems, biodiversity and natural resources. However, making progress and achieving this objective entails dealing with all trade-offs, negative externalities and benefits emerging from policies and combinations of policies presented previously.

Addressing Food Safety Issues Across Value Chains

Food safety is positioned at the intersection of agri-food systems and health, thus there are very strong interconnections of bi-directional links among food safety, livelihoods, gender equity and nutrition disciplines (Grace et al. 2018).

Food safety across the value chains must be ensured along all stages until consumption. Responsibilities lie with all actors, from producers to processors, retailers and consumers. Consumer behaviour in households regarding the storing (temperature) and handling of foods (cross-contamination) impacts strongly on the onset of food-borne intoxications. In the European Union, surveillance data indicate that most of the strong-evidence outbreaks in 2018 took place in a domestic setting (EFSA and ECDC 2019). The safety of food is a matter of growing concern, especially after the global estimation of the burden of food-borne disease comparable to that of HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis together, with low- and middle-income countries bearing 98% of the global burden (WHO 2015). Most of the known health burden comes from biological hazards (virus, bacteria, protozoa and worms), which cause acute intoxication that is easier to detect and control. Chronic effects due to chemicals (natural or processed contaminants, pesticide residues, etc.) are more difficult to be traced and quantified as to their actual impact on the disease burden. The Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases report (WHO 2015) quantified the burden of disease from aflatoxin, cassava cyanide and dioxins, and other studies have estimated the burden for four food-borne metals (arsenic, cadmium, lead and methylmercury), which is substantial (Gibb et al. 2019). Since temperature and humidity are important parameters for the growth of fungi, climate change is anticipated to have an impact on the presence of mycotoxins in foods.

The riskiest foods for biological hazards are livestock products, followed by fish, fresh vegetables and fruit (Grace et al. 2018). In addition to the disease burden, food-borne diseases in low- and middle-income countries also have a great impact on economic costs and market access (Unnevehr and Ronchi 2014). In recent years, the possible impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on health via food has gained a lot of attention, with multiple studies identifying the occurrence of micro and nanoplastic particles found in food commodities such as water, filtering molluscs and fish (Lusher et al. 2017; Toussaint et al. 2019; van Raamsdonk et al. 2020). Currently, there is considerable effort to standardise the methods of analysis and identify the health impact from dietary exposure.

Food scares happen from time to time, with the subsequent food incidents (real or perceived) causing a sudden disruption to the food supply chain and food consumption patterns with a high societal impact. In these situations, providing real-time information to consumers is very important so as to maintain confidence in the food supply. Contaminant-based food scares relating to the use of antibiotics, hormones and pesticides have occurred in a number of food and drink sectors and appear to be of more concern to consumers compared to hygiene standards and food poisoning (Miles et al. 2004). Explicit investigations into the aforementioned food scares and their cumulative impact on food purchase behaviour could help to further our understanding of consumer responses to food scares (Knowles et al. 2007).

There are many promising approaches to managing food safety in low- and middle-income countries, but few have demonstrated an impact at scale. Food safety management systems are designed to prevent, reduce or eliminate hazards along the food chain, which includes primary production (farms), processors, retail distribution centres, supermarkets, and retail food outlets (Ricci et al. 2017). Food safety control at primary production is achieved using good general hygiene practices. Food business operators should implement and maintain permanent procedures based on the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points principles (WHO and FAO 2006), which are effective in controlling most of the hazards during food production. Small-scale retail producers might have difficulties in Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points due to the complexity of some systems and a lack of both resources to implement and access to information and appropriate education. Transitions to circular food systems, local food systems, or short circuit systems are often slowed or hampered by current food safety regulations. Ensuring food safety, while enabling small-holder farmers or craft food companies to operate in local contexts, will be critical to facilitating the transition to more sustainable food systems and greater availability of healthy diets while supporting local economies.

To avoid confusion caused by multiple different national standards, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization established the Codex Alimentarius Commission to address safety and the nutritional quality of foods and develop international standards to promote trade among countries (Codex Alimentarius Commission 2007). The Codex Alimentarius establishes standards for maximum levels of food additives, maximum limits for contaminants and toxins, maximum residue limits for pesticides and veterinary drugs and gives indications for limits of microbiological hazards in a given food commodity. At the national level, government food safety systems monitor compliance with official standards through food inspections. While metrics are considered key to monitoring and improving performance, they can also have unintended consequences, including focusing efforts on the thing to be measured rather than the ultimate goal of improving the thing being measured, stifling innovation through standardisation, costs that increase in disproportion to benefits attained, incentivising perverse behaviour to game metrics and reduced attention to things that are not measured (Bardach and Cabana 2009), the balance and potential of large multinationals vs. small and medium-sized enterprises, short vs. long value chains, and low- and middle-income countries.

Even in higher income countries, small and medium-sized firms find it difficult to comply with complex and technocratic rules, measures and metrics that are characteristic of best practice food safety management systems and risk-based approaches: these methods are hardly applicable in low- and middle-income countries. The same applies for traceability, which only appears to be attainable in niche, high-value markets in low- and middle-income countries (Grace et al. 2018).

Local Producers and Value Chains, Income and Land Inequality

For many consumers, especially in low- and middle-income countries, local production is the main supplier of nutritious food (fruits, vegetables, pulses) and the primary provider of economic activity. Small and medium-sized farms produce critical nutrient diversity in rural areas (Herrero et al. 2017), and hence the transition to sustainable consumption requires support and value chain creation for linking food system actors (HLPE 2020).

As with any change, some people will be disadvantaged by the transition to healthy diets from sustainable food systems. It is important to provide support and transition options for potential losers impacted by the required changes to food systems (Herrero et al. 2020).

Many cities are playing more active roles in the development of city region food systems, notably recognising that environmental damage in areas within close proximity to cities impacts a large number of people, and that greater collaborations between cities and peri-urban spaces offers important opportunities for tackling environmental challenges while increasing the availability of healthy diets, and supporting stronger rural economies (e.g., the Paris Food System Strategy (Mairie de Paris 2015)). Vertical farming could provide opportunities for increasing food production in urban areas (Al-Kodmany 2018).

The Role of Trade in Open and Closed Economies

Trade is an essential instrument in the food system, but it is not always geared towards sustainable consumption. While trade can act as an insurance policy to local disruptions, it can also increase exposure to disruptions in external markets. This is evident in many low- and middle-income countries where trade in cheaper, ultra-processed food with long shelf lives competes with healthy dietary items. In many regions around the world (i.e., the Pacific, South America), this is likely a contributing factor to the high prevalence of obesity and increases in non-communicable diseases (Swinburn et al. 2019). However, trade also eases the leveraging of comparative advantages, which can allow production to be located where it is more efficient (Frank et al. 2018; IPCC 2019). This has been a key feature of scenarios for achieving greenhouse gas mitigation targets (IPCC 2019). However, when facing varied levels of regulation and power dynamics, trade can facilitate the outsourcing of environmental impacts of the food system to more vulnerable countries and individuals. Export-oriented value chains often are dominated by larger producers, who can concentrate market and political power as dominant producers and suppliers of food, as well as sources of employment and revenue to governments (Swinburn et al. 2019). These aspects are intertwined with the political economy of food and need to be accounted for.

It is also important to consider the impacts of the rising number of barriers to international trade on the affordability of nutritious foods (including non-tariff measures put in place to ensure food safety), as restrictive trade policies tend to raise the cost of food, which can be particularly harmful to net food-importing countries (FAO et al. 2020). Protectionary trade measures such as import tariffs and subsidy programmes make it more profitable for farmers to produce rice or corn than fruits and vegetables. According to data from Tufts University, removing trade protection across Central America would reduce the cost of nutritious diets by as much as 9% on average (FAO et al. 2020). The efficiency of internal trade and marketing mechanisms is also important, as these are key to reducing the cost of food for consumers and avoiding disincentives to the local production of nutritious foods.

The Political Economy of Food

Swinburn et al. (2019) demonstrated that the current food system has large power imbalances and conflicts of interest when large commercial interests in food manufacturing and trade exist. While some large food companies are interested in opportunities to increase their environmental sustainability, financial interests often prevail over sustainability concerns. Swinburn et al. (2019) articulates that changes in the regulatory environment and new incentives, combined with global efforts on sustainable trade, will be required to create the necessary accountability and shifts towards healthy diets.

Modifying Behavioural Changes

Most studies exploring the transitions towards healthy diets from sustainable food systems have focused on the technical feasibility of the diets and their production elements. Transition pathways and the levers for eliciting the required behavioural changes in consumption have received less attention (Garnett 2016; HLPE 2020).

Educating consumers to make healthy choices can modify behaviour in some cases. Educational campaigns in high-income countries have increased awareness and have also achieved some modest gains in fruit and vegetable consumption. However, most have not realised the target levels for consumption over the longer term (Brambila-Macias et al. 2011; Thomson and Ravia 2011; Rekhy and McConchie 2014). Certain people are more receptive to education on healthy diets than others. Providing nutritional information was found to change the behaviour of consumers already interested in nutrition, but was unable to influence consumers with low interest in nutrition (Lone et al. 2009). Conversely, marketing incentives for healthy diets have been found to be more effective for people who have less healthy eating habits (Chan et al. 2017). Educational activities are more effective when used in conjunction with environmental modifications, such as increasing the availability and accessibility of healthy dietary items (Van Cauwenberghe et al. 2010).

Altering food availability options can enhance healthy diets. A review of studies found that the strategic placement of fruit and vegetables could moderately increase fruit and/or vegetable choice, sales or servings (Broers et al. 2017). However, individual studies show mixed results. Furthermore, the provision of financial incentives to make healthy diets more affordable has been shown to increase consumption of fruits and vegetables (Olsho et al. 2016).

Taxes and front-of-pack information labels have been used with success to moderate the purchase of unhealthy dietary items, as well as influence reformulation of unhealthy products (Colchero et al. 2017; Roache and Gostin 2017; Taillie et al. 2020). Although the magnitude of effect ranges, there is evidence that fiscal measures such as taxes on unhealthy dietary items improve diets (Andreyeva et al. 2010; Brambila-Macias et al. 2011; Eyles et al. 2012; Niebylski et al. 2015). A sugar-sweetened beverage tax has reduced consumption of such drinks in the study cohorts in Berkeley, USA (Lee et al. 2019) and Mexico (Sánchez-Romero et al. 2020). A review on the effect of subsidies for healthy dietary items and taxation on unhealthy dietary items found evidence that taxation and subsidy intervention influenced dietary behaviours to a moderate degree. The study suggests that food taxes and subsidies should be a minimum of 10 to 15% and should both be implemented to improve success and effect (Niebylski et al. 2015).

Reducing Food Loss and Waste and Embracing Circularity

As discussed in Action Tracks 1 and 3, a critical component of rebalancing food systems is reducing food loss and waste. Food loss and waste currently accounts for significant losses of food availability around the world, and current estimates are, for food loss, 14% (FAO 2019) and, for food waste, 17% (United Nations Environment Programme 2021) of total production, depending on the type of commodity. In low- and middle-income countries, these losses occur mostly at the pre-consumer stage due to harvest and storage losses, while in OECD countries, they are more significant at the consumption stage (for example, sell-by dates). Circular food systems have been suggested as a mechanism for reutilising these biomass streams (Jurgilevich et al. 2016). For example, it has been estimated that circular livestock could produce 7–23 g of protein per capita/day while decoupling livestock from land use systems (Van Zanten et al. 2018). Microbial protein production in fermentation processes or through alternative foods (i.e., insects, algae) are considered part of these solutions (Parodi et al. 2018; Pikaar et al. 2018).

5 The Key Trade-Offs and Synergies

Food systems in low-, middle- and high-income countries are changing rapidly. Increasingly characterised by a high degree of vertical integration and high concentration, transitions in food systems are being driven by new technologies that are changing production processes, distribution systems, marketing strategies, and the food products that people eat (Stordalen and Fan 2018; Herrero et al. 2020).

In terms of synergies, the arguments for aligned action on healthy diets from sustainable food systems are attractive from multiple standpoints. The possibility of engaging in triple-win actions linking health, consumption and the environment presents a real opportunity to achieve numerous global commitments simultaneously, which could be desirable from a policy perspective. These include planned emissions reductions (United Nations 2015; IPCC 2019; Leclere et al. 2020), reductions in non-communicable diseases and malnutrition in all its forms, and achievement of SDG goals and targets (SDGs 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 12–16). These multi-sectoral opportunities will require increased concerted action and alignment at the global and national levels. While these synergies could potentially lead to human and planetary well-being, their achievement could also yield significant trade-offs that will require resolution (Herrero et al. 2021). Some of these are related to the following dimensions:

Multiple Environmental Trade-Offs

Changing consumption patterns can have impacts on the environmental footprints of the food system. Over a decade ago, Stehfest et al. (2009) demonstrated that reductions in the demand for animal-sourced foods could lead to reduced greenhouse gas emissions. These effects were mediated through reductions in methane production and carbon dioxide due to the use of less land and fewer animals for achieving consumption targets. More recently, studies integrating many environmental indicators (Springmann et al. 2018b; Van Zanten et al. 2018; Willett et al. 2019) confirmed those findings, but due to the compositions of the healthy diets with higher amounts of coarse grains, fruits, vegetables and nuts, the environmental impact of these diets remains high. The impacts on different locations are markedly different due to different limiting constraints (i.e., water scarcity). It is only when consumption is modified, waste is reduced, and productivity increased that improvements across all environmental metrics are obtained.

Trade-Offs with Affordability and Availability

A key trade-off of pursuing healthy diets from sustainable food systems is the increase in the costs of the diets in many countries, as a result of increasing the demand for nutrient-rich foods. A significant portion of the people living in extreme poverty are the two billion who struggle to access sufficient foods and suffer acute caloric and nutrient deficiencies. Even the cheapest healthy diet costs 60% more than diets that only meet the requirements for essential nutrients. Examples like the EAT-Lancet diet are not affordable for an estimated 1.5 billion people (Hirvonen et al. 2020, Table 1) and almost double the cost of the nutrient adequate diet; it is five times as much as diets that meet only the dietary energy needs through a starchy staple (FAO et al. 2020). This is of concern, as the high cost and unaffordability of healthy diets is associated with increasing food insecurity and different forms of malnutrition, including child stunting and adult obesity. The unaffordability of healthy diets is due to their high cost relative to people’s incomes. Healthy diets are unaffordable for more than 3 billion poor people in low-, middle- and high-income countries, and more than 1.5 billion people cannot even afford a diet that only meets required levels of essential nutrients (FAO et al. 2020; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2020). The cost of a healthy diet is much higher than the international poverty line, established at USD 1.90 purchasing power parity per day. At a global level, on average, a healthy diet is not affordable, with the cost representing 119% of mean food expenditures per capita per day. Where hunger and food insecurity are greater, the cost of a healthy diet even exceeds average national food expenditures. The cost of a healthy diet exceeds average food expenditures in most countries in the Global South. 57% or more of the population throughout sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia cannot afford a healthy diet (FAO et al. 2020).

Part of the reason why many of the components of healthy diets are expensive follow the basic economics of supply and demand. In many cases, production of key dietary components does not meet the required demand, even at the global level, and therefore their prices are high. Mason-D’Croz et al. (2019) recently demonstrated this for fruits and vegetables, a key component of healthy diets. The study concluded that even under optimistic socioeconomic scenarios, future supply will be insufficient to achieve recommended levels in many countries. Even where supply exists (i.e., India), internal barriers like poorly developed markets mean that increased incomes do not necessarily result in increased consumption of healthy diets (Fraval et al. 2019).

Low market access can be a large barrier to achieving a healthy diet. A ‘food desert’ refers to areas with poor access to a retail outlet with fresh produce, where cheap, ultra-processed, and unhealthy dietary items can predominate. While food deserts are often associated with economically disadvantaged communities in high-income countries (Walker et al. 2010; Ghosh-Dastidar et al. 2014), they also affect poor urban communities in low- and middle-income countries, particularly newly urban communities (Battersby and Crush 2014). Food deserts can also occur in areas that lack refrigeration, or have harsh environmental conditions or poor storage conditions, far from towns, where highly processed foods can be stored easily (i.e., the Pacific). Vertical farming may provide opportunities for food production in urban areas, where available land for farming is limited and expensive. Currently, economic feasibility, codes, regulations, and a lack of expertise are major obstacles to implementing vertical farming (Al-Kodmany 2018).

Trade-Offs with Pandemics and Zoonosis

In contexts in which animal-sourced food consumption is higher than recommended, shifting towards greater plant consumption would also have the added benefit of preserving ecological systems and wildlife and avoiding the spillover of zoonotic agents (mainly viruses) from wildlife to humans. In contexts in which animal-sourced food consumption is critical for maintaining appropriate intake of essential nutrients, it is vitally important to scale up a ONE HEALTH approach that enables environmental, animal, and human health (Wood et al. 2012; Gale and Breed 2013) while avoiding causing a public health threat. In recent years, there have been several examples of such spillovers (Ebola, SARS, MERS and COVID-19) with dramatic economic and public health consequences and the potential to cause global pandemics (see Box 1). A consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is the disruption of global, or concentrated, value chain production in terms of affordability and food availability; inversely, many local value chains have seen increases in production and market shares.

The global burden of disease from food consumption is very different across the globe (WHO 2015), and it is, in large part, produced by zoonotic infections. Today, the largest food source attributions in food-borne intoxications are from food of animal origin in the developed world. Antimicrobial resistance contributes significantly to the burden of disease across the globe and constitutes a threat to public health.

Box 1: The impact of COVID19 on Food Systems

Food

The new type of respiratory tract disorder COVID-19 is based on an infection with the new type of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). The main target organs of coronaviruses in humans are the respiratory tract organs. The scientific data collected so far suggests that the virus is transmitted mainly via small respiratory droplets through sneezing, coughing, or when people interact with each other in close proximity, as may happen in slaughterhouses and meat-processing plants, where environmental conditions seem more favourable than in other places to the propagation of the virus. In fact, there have been COVID-19-related outbreaks at some slaughterhouses and meat-processing plants worldwide, which has led to risk management measures to contain the propagation of the virus from occupational exposure among workers and related communities. Up to now, there is no evidence that food, including meat, is a source or transmission route of SARS-CoV-2. Meat, like any other food, might theoretically be contaminated by SARS-CoV-2. This could happen with food in the same way that it could happen with any other animated or non-animated surface. For example, food might be exposed to the virus through contamination by an infected person during food manipulation and preparation. This does not mean however that the food ingested would cause infection for the consumer. As indicated above, there is so far no evidence of transmission of this virus through ingestion of any type of food. Several food safety agencies and organisations worldwide have concluded that there is no evidence of food-borne transmission of the virus.

Pandemics and value chains

COVID19 is an example of the importance of ONE HEALTH approach as it is a zoonosis (disease transmitted from animals to humans). It is well known that damaging ecological systems might lead to spillovers of zoonotic agents (mainly viruses such as Ebola, SARS, MERS) outside their original environment with dramatic economic and public health consequences and the potential to cause global pandemics. A consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is the disruption of global, or concentrated value chain production in terms of affordability and food availability; inversely, many local value chains have seen increases in production and market shares.

Waste

In response to COVID-19, hospitals, healthcare facilities and individuals are producing more waste than usual, including masks, gloves, gowns, other protective equipment and single-use plastics that could be infected with the virus. Infected medical waste could lead to public health risks, as well as environmental risks add to land, riverine and marine pollution.

Political Economy Trade-Offs

Broad awareness of the positive or negative consequences of food system changes from nutritional, health, environmental and livelihood perspectives among key policy-makers is key to policy changes that facilitate a transition to healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Increased biodiverse agricultural production can result in increased employment and income, leading to growing demand for (healthy) food, provided that there is strong consumer awareness regarding diets and their consequences, and provided that there are few competing demands on incomes, especially of the poor.

The political impediments to achieving healthy and sustainable diets are numerous. Maintaining the status quo benefits the current actors of the food system, hence the inertia for change (Béné et al. 2020; Fanzo et al. 2020; Herrero et al. 2020). Additionally, many public policies are not geared towards creating sustainable food systems, such as a lack of research and investment in nutritious foods at the expense of cereals or the creation of food environments that promote nutritious foods. The current system rewards economic efficiency rather than sustainability and the production of nutrition foods (Béné et al. 2020). Therefore, farmers have little incentive to change production practices. At the same time, large private companies exercise disproportionate control over the food agenda, and this is not necessarily aligned with a health and sustainability agenda needed to transform the food systems.

Technology will be important, but even with the best intentions, assurance that equitable and fair distribution of its availability and impacts are taken into account when designing transition pathways remains elusive (Herrero et al. 2021). Critical dialogues and transparency in designing these transition pathways must be developed with a broad range of stakeholders, and with mutual respect for values and motivations (Herrero et al. 2021).

6 Solutions and Actions

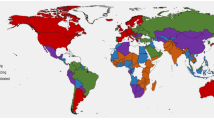

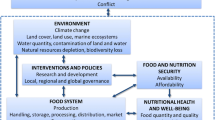

Solutions for enabling the shift towards more sustainable consumption need to be defined around cross-cutting levers connecting policy reform, coordinated investment, accessible financing, innovation, traditional knowledge, governance, data and evidence, and empowerment (Béné et al. 2020). It is important to identify and learn from the success stories of individuals and groups that have shifted to healthy diets from sustainable food systems and use these examples to clearly inform policy-makers, practitioners and the public. Figure 1, from the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2020), synthesises the range of critical actions necessary to effectively create transition towards healthy and sustainable diets. We develop this list further into a broader set of actions for implementation in different contexts, which are presented below, following the categories of actions in Béné et al. (2020).

Priority policy actions to transition food systems towards sustainable, healthy diets. (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2020)

Economic and Structural Costs

Off-set the economic and structural costs associated with the transition to more healthy and sustainable diets.

-

Develop policies and investments across food supply chains (food storage, road infrastructure, food preservation capacity, etc.) that are critical to cutting losses and enhancing efficiencies so as to reduce the cost of nutritious food (FAO et al. 2020).

-

Provide support and transition options for potential losers impacted by the required changes to land use, food production practices, storage and processing technologies, food environment, distribution and food waste.

-

Direct funding towards a healthy and sustainable food system, e.g., repurpose funding from monoculture crops, or foods that, when overproduced, are detrimental to health and the environment (e.g., sugar and its derivatives).

-

Facilitate easier access to loans from financial institutions, or lands from municipalities, notably for young farmers, both men and women.

-

Pilot and scale behaviour change interventions that are effective in reducing consumer food waste and increasing the adoption of healthy and sustainable diets.

-

Invest in innovative food-related infrastructure and logistical systems that will improve the efficiency of food supply chains, particularly for urban consumers.

-

In low and lower middle-income countries, facilitate increased consumption of nutrition foods by encouraging those with access to land to grow more such foods themselves or by exchange within the local communities.

-

Encourage the creation of rural food markets in cities based on the production and sale of indigenous and sustainably produced foods grown by local farmers.

-

Break existing policy silos so as to facilitate food system transformations, providing support for a major policy drive to enhance the cultivation of indigenous food systems. Many native foods have biological components that can contribute to nutritionally-rich and healthy diets. Priority actions should be taken to promote research into these native foods worldwide.

Challenge the Current Political Economy

-

Encourage large food system actors to transition to the provision of healthy diets through incentives that are matched with penalisation or taxes for overproduction of unhealthy dietary items, or the use of degradative production practices.

-

Develop trade policies and input subsidy programmes that can change incentives towards nutritious foods like fruits and vegetables. This also implies improvement of food safety to reduce non-tariff trade measures so as to increase the availability of healthy diets.

-

Promote social and environmental aspects of corporate performance to be equal to financial performance.

-

Develop regulatory measures such as taxes and front-of-pack information labels to limit the sale and production of unhealthy products.

-

Change the global regulatory environment, including international trade and investment agreements, to favour healthy diets from sustainable food systems.

-

Promote divestment to avoid harm. This includes the exclusion of certain companies from investment portfolios.

-

Encourage a culture of corporate responsibility in the food industry to investigate the level of sustainability of products. Encourage social impact investing. This aims to generate a positive social impact from investment decisions, alongside financial return.

-

Empower consumers to demand healthy, sustainable products and reject unhealthy products.

-

Encourage consumers to demand increased accountability for large food system actors.

-

Encourage institutions, for example, schools, health care facilities and government offices, to transition to healthier diets through improved nutrition standards, which flow on to improve the nutritional quality of meals served in those institutions (Gearan and Fox 2020).

-

Gear public policies towards creating healthy diets from sustainable food systems.

Influencing Consumer Demand

The Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2020) recommends the following four priority lines of action, while also acknowledging that far better evidence of what works in low- and middle-income countries is required:

-

Define principles of engagement between the public and private sectors, leading to the leveraging of expertise and resources and influence of the businesses in the food sector. This recognises the considerable role of firms in driving consumer choices, too often employed in ways that are not conducive to healthy diets from sustainable food systems. A new relationship between public and private actors is needed, so that they can work together on a common agenda.

-

Upgrade and improve food-based dietary guidelines and promote enhanced knowledge about the implications of dietary choices. For example, food-based dietary guidelines seldom take account of issues of food system sustainability. Moreover, policy-makers in many governments need to take account of food-based dietary guidelines in developing policies, both in relation to the food system and in wider areas of government (e.g., relating to infrastructure development, safety nets, etc.).

-

Improve regulation of advertising and marketing. This is mentioned in the AT2 paper and discussed further in the Foresight report, which addresses, in particular, the ineffectiveness of businesses self-regulating.

-

Implement behavioural nudges via carefully designed taxes and subsidises.

Education and Cultural Norms

The role of education will be pivotal in changing consumption patterns at many levels. It can facilitate a cultural shift in consumer perceptions and behaviour.

-

Provide education and clarity for consumers about what constitutes a healthy and sustainable diet and educate consumers to make healthy choices, coupled with other incentives to improve success and effect.

-

Invest in female, minority and youth leadership and technical and managerial skills, which are key to promoting the more equitable and sustainable participation of women in food supply chains, as producers, processors, business leaders and consumers, using women’s self-help groups as an example.

-

Alter food availability options to promote healthy diets.

-

Invest in large-scale awareness campaigns that connect food consumption patterns with health, the environment and, specifically, climate change outcomes.

-

Engage in school education programmes on healthy diets from sustainable food systems to ensure that the next generation has a novel conceptualisation of what the food system can offer.

-

Include sustainability-of-consumption learning modules in medical school curricula worldwide.

Equity and Social Justice

Manage equity and social justice to provide the greatest benefit to all:

-

Identify the current consumption patterns of households.

-

Encourage regions to transition to more healthy and sustainable diets in a culturally appropriate manner.

-

Systematically use full supply chain traceability to promote internal transparency, as has been shown to work (Bush et al. 2015). This could potentially be a way to promote social justice in the industry and protect people employed in low- and middle-income countries.

-

Deploy safety nets to protect the poor against dynamic food system transitions that might render them vulnerable and disenfranchised. This will require international coherence and action (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2020).

Governance and Decision Support Tools

-

Invest in additional knowledge, skills, data and tools needed to identify, prioritise and manage trade-offs and competing priorities.

-

Establish standardisation and clear labelling.

-

Develop tools for measuring consumer and retail food waste at the national level, so as to understand the scale of the problem, identify hotspots for targeted action, and track progress towards SDG 12.3.

-

Increase adherence to principles of circular economy recycling and the repurposing of food waste until they become the norm.

-

Rationalise food-related sustainability standards. Such initiatives, which set standards for sustainable production and often include certification programmes to verify compliance, can be used as tools to drive consumer choice on the one hand and to channel and enhance the nascent demand for more sustainable food systems into market-related investments on the other. However, some regulatory approaches and private sector-led schemes create barriers, primarily because of the costs of compliance and the potential exclusion of actors. Nevertheless, some excellent examples exist within the salmon industry (Global Salmon Institute 2020).

7 Conclusions

A shift towards sustainable consumption patterns is necessary to harmonise global societal and environmental goals and for humanity to prosper sustainably and equitably in the coming years. Transitioning towards healthy diets from sustainable food systems at the country level is essential to achieving this, together with strategies for managing waste reduction and increasing productivity.

The range of constraints preventing this transition include the lack of availability and access to healthy diets, the costs of eating healthily, poor food environments, lack of incentives and standards, food safety, pandemics and, in many cases, a lack of political will. These are not insurmountable. Many strategies exist for circumventing these problems, including awareness-raising, behaviour change interventions in food environments, food education, strengthened urban-rural linkages, improved product design, investments in food system innovations, public-private partnerships, public procurement, and novel strategies for food waste management.

The role of science and innovation will be essential in deploying these interventions at scale and at low costs, and for minimising the potential trade-offs that may arise. Transparent multi-stakeholder dialogues will be key at all stages of planning the appropriate transition pathways towards our desired global goals of healthy diets, healthy ecosystems and prosperity for all.

References

Afshin A et al (2019) Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393(10184):1958–1972. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

Aleksandrowicz L et al (2016) The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: a systematic review. PLOS ONE 11(11):e0165797. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165797. Edited by A. S. Wiley

Al-Kodmany K (2018) The vertical farm: a review of developments and implications for the vertical city. Buildings 8(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings8020024

Andreyeva T, Long MW, Brownell KD (2010) The impact of food prices on consumption: a systematic review of research on the price elasticity of demand for food. Am J Public Health:216–222. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.151415. American Public Health Association

Baker P et al (2020) Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev (February), pp. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13126

Bardach NS, Cabana MD (2009) The unintended consequences of quality improvement. Curr Opin Pediatr 21(6):777–782. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283329937

Battersby J, Crush J (2014) Africa’s urban food deserts. Urban Forum 25(2):143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-014-9225-5

Béné C et al (2020) Five priorities to operationalize the EAT-Lancet Commission report. Nat Food 1(8):457–459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0136-4

Brambila-Macias J et al (2011) Policy interventions to promote healthy eating: a review of what works, what does not, and what is promising. Food Nutr Bull 32(4):365–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651103200408

Broers VJV et al (2017) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of nudging to increase fruit and vegetable choice. Eur J Public Health 27(5):912–920. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx085

Bush SR et al (2015) Sustainability governance of chains and networks: a review and future outlook. J Clean Prod 107:8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.10.019

Camaréna S (2020) Artificial intelligence in the design of the transitions to sustainable food systems. J Clean Prod:122574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122574. Elsevier Ltd.

Campbell BM et al (2017) Agriculture production as a major driver of the earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecol Soc 22(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09595-220,408

Chan EK, Kwortnik R, Wansink B (2017) McHealthy. Cornell Hosp Q 58(1):6–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965516668403

Codex Alimentarius Commission (2007) Codex Alimentarius Commission: Procedural Manual. FAO &WHO, Rome. Available at: https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=P2zOGjHGoyIC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Codex+Alimentarius+Commission+2007&ots=aSg5DRv0sY&sig=R9DcaDIUKJRSI2IKEMno-jiNABg#v=onepage&q=CodexAlimentariusCommission2007&f=false. Accessed 4 Nov 2020

Colchero MA et al (2017) In Mexico, evidence of sustained consumer response two years after implementing a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Health Aff 36(3):564–571. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1231

Daru J et al (2018) Risk of maternal mortality in women with severe anaemia during pregnancy and post partum: a multilevel analysis. Lancet Glob Health 6(5):e548–e554. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30078-0

Development Initiatives (2020) Global nutrition report, The global nutrition report’s independent expert group. https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896295841.

Downs JS, Loewenstein G, Wisdom J (2009) Strategies for promoting healthier food choices. Am Econ Rev:159–164. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.2.159

Eaton JC et al (2019) Effectiveness of provision of animal-source foods for supporting optimal growth and development in children 6 to 59 months of age. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2(2):CD012818. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012818.pub2

EFSA and ECDC (2019) The European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J 17(12). https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5926

Eyles H et al (2012) Food pricing strategies, population diets, and non-communicable disease: a systematic review of simulation studies. PLoS Med 9(12):e1001353. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001353. Edited by D. Stuckler

Fanzo J et al (2020) A research vision for food systems in the 2020s: defying the status quo. Glob Food Secur 26:100397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100397

FAO (2019) The state of food and agriculture. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315764788.

FAO et al (2020) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2014.2300145

FAO & WHO (2019) Sustainable healthy diets, sustainable healthy diets. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca6640en

Frank S et al (2018) Structural change as a key component for agricultural non-CO2 mitigation efforts. Nat Commun 9(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03489-1

Fraval S et al (2019) Food access deficiencies in Sub-Saharan Africa: prevalence and implications for agricultural interventions. Front Sustain Food Syst 3(5):104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00104

Gale P, Breed AC (2013) Horizon scanning for emergence of new viruses: from constructing complex scenarios to online games. Transbound Emerg Dis 60(5):472–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1865-1682.2012.01356.x

Garnett T (2016) Plating up solutions. Science 353:1202–1204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016000495

Gearan EC, Fox MK (2020) Updated nutrition standards have significantly improved the nutritional quality of school lunches and breakfasts. J Acad Nutr Diet 120(3):363–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.10.022

Ghosh-Dastidar B et al (2014) Distance to store, food prices, and obesity in urban food deserts. Am J Prev Med 47(5):587–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.005

Gibb HJ et al (2019) Estimates of the 2015 global and regional disease burden from four foodborne metals – arsenic, cadmium, lead and methylmercury. Environ Res 174(December 2018):188–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.062

Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2020) Future food systems: for people, our planet, and prosperity

Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2021) Harnessing aquaculture for healthy diets. London

Global Salmon Institute (2020) Sustainable salmon farming: the future of food

Grace, D. et al. (2018) Food safety: food safety metrics relevant to low and middle income countries, food safety. London

Herforth A et al (2019) A global review of food-based dietary guidelines. Adv Nutr 10(4):590–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy130

Herrero M et al (2017) Farming and the geography of nutrient production for human use: a transdisciplinary analysis. Lancet Planet Health 1(1):e33–e42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30007-4

Herrero M et al (2020) Innovation can accelerate the transition towards a sustainable food system. Nat Food 1(5):266–272. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0074-1

Herrero M et al (2021) Articulating the effect of food systems innovation on the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet Health 5(1):e50–e62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30277-1

Hirvonen K et al (2020) Affordability of the EAT-Lancet reference diet: a global analysis. Lancet Glob Health 8(1):e59–e66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30447-4

HLPE (2020) Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030’, Research Guides. Available at: https://research.un.org/en/foodsecurity/key-un-bodies

Iannotti LL et al (2017) Eggs in early complementary feeding and child growth: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 140(1):20163459. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3459

Imamura F et al (2015) Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Health 3(3):e132–e142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70381-X

IPCC (2019) IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse gas fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems: Summary for Policymakers, IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Land. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0538

Jarmul S et al (2020) Climate change mitigation through dietary change: a systematic review of empirical and modelling studies on the environmental footprints and health effects of “sustainable diets”. Environ Res Lett 15(12):123014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abc2f7

Jurgilevich A et al (2016) Transition towards circular economy in the food system. Sustainability 8(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010069

Knowles T, Moody R, McEachern MG (2007) European food scares and their impact on EU food policy. Br Food J:43–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700710718507. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Leclere D et al (2020) Bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity needs an integrated strategy. Nature:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2705-y

Lee MM et al (2019) ‘Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption 3 years after the Berkeley, California, sugar-sweetened beverage tax’. Am J Public Health. American Public Health Association Inc., pp. 637–639. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.304971

Lele U, Goswami S, Mekonnen MM (2021) Achieving sustainable healthy food systems: the need for actual food consumption data for measuring food insecurity and its consequences. Econ Polit Wkly LVI(7):40–47

Lone TA et al (2009) Marketing healthy food to the least interested consumers. J Foodserv 20(2):90–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4506.2009.00131.x

Lusher A, Hollman P, Mendoza-Hill J (2017) Microplastics in fisheries and aquaculture: Status of knowledge on their occurrence and implications for aquatic organisms and food safety. Rome

Mairie de Paris (2015) Sustainable Food Plan 2015–2020. Paris.

Mason-D’Croz D et al (2019) Gaps between fruit and vegetable production, demand, and recommended consumption at global and national levels: an integrated modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 3(7):e318–e329. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30095-6

Mateo-Sagasta J, Zadeh SM, Turral H (2017) Water pollution from agriculture: a global review Executive summary

McGovern ME et al (2017) A review of the evidence linking child stunting to economic outcomes. Int J Epidemiol 46(4):1171–1191. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx017

Miles S et al (2004) Public worry about specific food safety issues. Br Food J 106(1):9–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700410515172

Niebylski ML et al (2015) Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: a systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition:787–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2014.12.010. Elsevier Inc