Abstract

To keep physically active is key to live a long and healthy life. It is therefore important to invest in research targeting the uptake of physical activity by the ageing population. This paper presents an overview of concluded EU-funded research projects which address the subject of physical activity among older adults. From an initial set of 330 projects, 29 are analyzed in this meta-review that describes the projects, its goals, types of physical activity promoted, and technologies used. Entertainment technologies, in particular exergames, emerge as a frequent approach.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Since the 1960’s that global average life expectancy had not had such a fast increase as it did between 2000 and 2016 and, after an increased by 5.5 years, global life expectancy at birth in 2016 was 72.0 years [1]. While the evidence of people living longer marks a significant achievement for humankind, it also poses societies with the challenge of supporting citizens to live a healthier life, if they are to experience both a longer and satisfying extended life spam. Partaking in physical activity and/or exercise training programs can reduce the impacts of aging and contribute to improvements in health and well-being [2, 3]. The importance and benefits of engaging in physical activity for health promotion are numerous and range from improvements in depression [4] to preventing or slowing down disablement due to chronic diseases [5].

International organizations have been working with researchers, governments, and decision makers to ensure that physical activity becomes an important component of the daily life of each citizen. The World Health Organization (WHO) offers global recommendations on physical activity for health [6], where different levels of physical activity are recommended for different age groups. The specific guidelines for people aged 65+ recommend aerobic physical activity, muscle strengthening activities, as well as balance training activities [7]. In particular, per week, older adults should engage in 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or in at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity (or equivalent combinations). Aerobic physical activity should be complemented with muscle-strengthening activities, involving major muscle groups, two or more days a week. In addition, it is suggested that older adults engage in physical activity that promotes balance three or more days per week, with this recommendation particularly applying to older adults with poor mobility. Recognizing the limitations imposed by specific health conditions, the WHO underlines that, if under limiting circumstances, older adults should be as physically active as their abilities and conditions allow.

All Europe Union (EU) member states are advised to implement the WHO guidance documents [8]. However, not all EU member states follow those recommendations, with some using instead similar guidelines from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or from the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, and the American College of Sports Medicine [9].

During the last decade, aging has been part of the priorities in the agenda of the European Commission, with several initiatives targeting active aging and healthy aging. Several research projects have been funded addressing the ageing challenge. This paper presents a review and comparison of projects concerning physical activity and older adults, aiming to understand how the EU has been prioritizing the area and how projects have been addressing the subject. Two main sources of information are used to retrieve relevant projects: (i) The Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS) database [5], the primary public repository and portal to disseminate information on all EU-funded research projects, and (ii) The Active and Assistive Living (AAL) Programme Website [6], a funding activity which specifically targets the improvement of life conditions of older adults.

2 Method

The goal of this research was to identify completed EU-funded collaborative research projects, which had encouraged the uptake of physical activity among older adults and aimed at promoting health and well-being, to then determine their characteristics and investigate the approaches taken by such projects to achieve their goals. Besides understanding the extent of the EU efforts in this area, this research wanted to understand if physical activity was an important goal in those projects and if/what specific technologies were being utilized to support physical activity.

In order to identify EU-funded collaborative research projects, this study reviewed two online resources: the CORDIS database [10] and the AAL Website [11]. To determine relevant projects to include in this meta-review, i.e.: projects targeting the uptake of physical activity among older adults with a view promote their health and well-being, inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined. Projects targeting older adults, involving some sort of exercise and/or physical activity, aiming at health and well-being, and which had been concluded would be included. Projects involving only one single European country, or focusing solely on health monitoring aspects, biology studies, or on developing aids (e.g. walking aids) would be excluded.

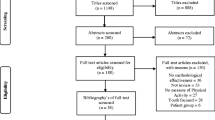

Building upon these resources and criteria, this research then followed a number of steps (see Fig. 1 for an overview). First, it was necessary to retrieve all potentially interesting projects from the CORDIS database, for which five search stringsFootnote 1 were used. All projects funded by the AAL programme were deemed interesting, thus no specific search was needed to retrieve relevant projects from this source. Once a pool of projects was created, each project was screened, initially based on its title and short description, and then again, considering the full descriptions available online. In cases where information was insufficient to determine the relevance of the project, a quick search through the project website (if available) was made. Finally, projects, which remained in the data set, were analyzed with a view to addressing the research questions.

3 Results and Analysis

The initial set of results included 455 records: 170 consisting of all concluded projects listed in the AAL website and 285 retrieved from the CORDIS database. Once repeated records were removed, 160 individual projects remained from the CORDIS database, which resulted in a pool of 330 eligible projects. After reviewing the project’s titles and short descriptions, 106 projects remained in the dataset and were further analyzed based on their full descriptions and, whenever needed, also based on their websites. 67 results were excluded at this stage, two of them because they referred to Strategic Research Agendas, and the remaining because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. An extra ten projects were removed because their websites were no longer available and the information displayed in the CORDIS and AAL websites was rendered insufficient to make a proper assessment of the project’s approach and activities. Figure 1 presents an overview of the process followed to retrieve the 29 projects identified as relevant and that form the basis for this research. The table in Appendix 1 shortly describes the 29 projects included in this meta-review.

3.1 Characteristics of the Projects Included in the Meta-review

The 29 projects analyzed represent €101 millions of investment, from which €65 millions came from public/EU contribution. Nine different funding programs have funded these projects: seven by FP7-ICT, five by AAL-Call4, three by AAL-Call1, three by AAL-Call2, three by AAL-Call5, three by AAL-Call6, two by FP7-Health, two by CIP, and one by H2020-EU.3.1. On average each of those projects lasted for 35.17 months (Max. 42, Min. 24) and cost an average of €3.5 millions (Max. €7.4 millions, Min €1.4 millions), with and average of €2.2 millions (Max. €5.7 millions, Min. €33.7 thousands) of public contribution. Those projects were more often coordinated by Germany (seven projects), followed by Spain (four projects), the Netherlands (four projects), France (three projects), Italy (three projects), and Switzerland (two projects). Countries such as Austria, Finland, Poland, Denmark, Greece, and Israel coordinated one project each. The remaining countries involved were diverse, often including the participation of more than one partner from the same country. The size of the consortia was also diverse involving on average 8.3 partners (Max. 14, Min. 5).

3.2 Goals, Approaches, and Strategies

All 29 projects included in this meta-review foster the uptake of physical activity among older adults to some extent. The table in Appendix 2 captures the most important aspects analyzed in each of the projects included for review, such as: the goals, types of physical activity, and approaches followed by the projects, namely in terms of technology used and evidence of entertainment-related attributes. These aspects are detailed in the following subsections.

Main Goals of Projects.

Into what concerns to the main goals of the projects, from the 29 projects analyzed, 25 have physical activity and/or its promotion as its main goal. However, five of these projects have parallel goals, such as: providing dietary/nutrition advice, promoting cognitive training, and promoting stress management at work. For the remaining four projects, physical activity was a side goal. Projects claimed broader health improvements, from physical to cognitive and social, with most projects aiming to improve more than one of these areas. While nine projects had physical health in the outlook, seven aimed at physical and social health, six at physical and cognitive health, and another seven aimed to improve all three areas. Another aspect investigated was whether the projects were aiming at specific health conditions, for which the analysis concluded that most projects (19) did not aim at any specific condition. The remaining projects were looking into fall prevention (four projects), stress (two projects), chronic conditions, stroke, rehabilitation, loneliness and also malnutrition and cognitive decline.

Type of Physical Activity Encouraged by Projects.

When it comes to the type of physical activity promoted, the majority of the projects (20) provided no specific details about the kind of physical activity targeted. The remaining nine projects resorted to different types of activities, with two projects resorting to all three main types of activities listed in the WHO recommendations, as described in Sect. 1. The exercises included ranged from simple chair-based exercises and walking to biking, hiking, gardening and the use of treadmills.

Nature of Technology Used.

When analyzing the projects concerning the nature of the solutions they propose to address their goals, it is noteworthy that a significant number (19 out of 29) of the projects resorts to digital technology to achieve their objectives and that those same projects employ some sort of entertainment technology to do soFootnote 2. The most popular approach, employed by 12 projects, is to use games, namely exergames and serious games, to motivate to exercise. Another tendency, although less prevalent, is the use of virtual coaches which is observed in six projects. Several projects offer the possibility of defining personalized programs and of facilitating the exercise to take place in the home of the older person. Yet another commonality among projects is the monitoring of both physical activity and health conditions, as well as the use of both sensor technology and approaches to behavior change.

4 Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The analysis of the projects included in this meta-review shows that entertainment technologies, in particular games in the form of serious games and exergames, are indeed a popular approach among EU-funded collaborative research projects to address physical activity targeting older adults. From the 29 projects analyzed, 19 use some sort of entertainment technology to achieve their goals. It is important to note that this study looked only at projects, which have already been concluded. Given the rising interest in games, serious games, exergames, and gamification in recent years, it is likely that the number of projects using technology and entertainment would be even higher in the near future, when ongoing projects would have been completed and thus included in the research.

To correctly interpret the results presented in this study it is important to highlight that conclusions were solely drawn upon the analysis of information which is publicly available online, therefore interpretations may be based on incomplete descriptions. To this adds the fact that a single researcher performed the research and some level of subjectivity should be expected. Furthermore, projects were retrieved from only two sources, so an additional more exhaustive search and inclusive study warrants further investigation and fully fledged conclusions and findings. In the future, it would be interesting to extend the research to the study of the specific characteristics of the entertainment approaches employed and the understanding of the most effective ones.

Notes

- 1.

Five searches made: ‘active’ AND ‘ageing’ AND ‘physical’ AND ‘health’ AND ‘activity’ AND contenttype=‘project’; ‘senior’ AND ‘exercise’ AND contenttype=‘project’; ‘ageing’ AND ‘health’ AND ‘exercise’ AND contenttype=‘project’; ‘active’ AND ‘ageing’ AND ‘exercise’ AND contenttype=‘project’; ‘old’ AND ‘exercise’ AND contenttype=‘project’.

- 2.

Appendix 2 presents an overview of the projects included in this meta-review, where the projects that clearly resort to entertainment technologies are indicated in Bold Underline; projects in which this connection is not so clear are indicated in Underline, and projects where this link is not apparent are in plain text. The same table also displays information regarding the goals, types of physical activities, and approaches followed by the projects.

References

WHO—Life expectancy, WHO. http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends_text/en/. Accessed 07 July 2018

Ciolac, E.: Exercise training as a preventive tool for age-related disorders: a brief review. Clinics 68(5), 710–717 (2013)

Chodzko-Zajko, W.J., et al.: Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41(7), 1510–1530 (2009)

Silveira, H., Moraes, H., Oliveira, N., Coutinho, E.S.F., Laks, J., Deslandes, A.: Physical exercise and clinically depressed patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychobiology 67(2), 61–68 (2013)

Tak, E., Kuiper, R., Chorus, A., Hopman-Rock, M.: Prevention of onset and progression of basic ADL disability by physical activity in community dwelling older adults: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 12(1), 329–338 (2013)

WHO—Global recommendations on physical activity for health, WHO. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/. Accessed 05 July 2018

WHO—Physical activity and older adults, WHO. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_olderadults/en/. Accessed 10 Apr 2016

EU Working Group “Sport and Health”: EU Physical Activity Guidelines: Recommended Policy Actions in Support of Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (2008)

WHO Regional Office for Europe: Factsheets on Health-enhancing Physical Activity in the 28 European Union Member States of the WHO European Region (2015). http://ec.europa.eu/sport/library/factsheets/eu-wide-overview-methods.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr 2016

CORDIS—European Commission. https://cordis.europa.eu/home_en.html. Accessed 05 July 2018

Active and Assisted Living Programme—ICT for ageing well. http://www.aal-europe.eu/. Accessed 05 July 2018

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1: Projects Descriptions

Acronym | Project description |

|---|---|

GameUP | Sustain mobility of older adults through exergames that include exercises defined by physiotherapists. The system developed by the project has a coach who advises and sets goals for the older person |

AIB | Create a process and technologies to covering the full chain of fall risk management, from assessment, to preventive recommendations, care plan, and interventions for fall prevention |

FARSEEING | Develop and test a falls management service (for prevention and prediction), together with assessment of exergames to improve strength and balance, thus reducing risk of falls |

IS-ACTIVE | To devise a person-centric healthcare solution for older adults with chronic conditions based on miniaturized wireless inertial sensors, which provide distributed motion capture and intelligent recognition of activities |

A2E2 | A²E² aims at breaking sedentary life styles though ambient virtual coaching motivating elderly before, during and after daily activities. A²E² allows for systematic interaction and adaptive feedback and selection of tasks |

Join-In | Develop a social networking platform for elderly citizens to encourage and support communication and socializing. Solution includes computer game to enhance cognitive abilities, biking exergames, and other video exercises |

V2me | Increase integration of older people in the society through the provision of advanced social connectedness and social network services and activities |

iStoppFalls | Develop technologies which can be integrated in daily life practices of older people living at home, and allow for continuous exercise training, reliable fall risk assessment, and appropriate feed-back mechanisms |

Long-Lasting Memories | The LLM platform that targets mind, body and fitness through three components: the Physical Training, the Cognitive Training and the Independent Living Component |

MOB MOTIVATOR | Motivate older adults to increase physical activity and exercise cognitive skills through an at-home system based on gaming environment that provides a truly innovative and enjoyable approach to healthy living and ageing |

PAMAP | PAMAP helps patients at home to perform their rehabilitation exercises by monitoring and providing feedback to patients and their caregivers about level of activity |

Rehab@Home | Rehabilitation after stroke at home with serious games in order to create the necessary motivation to continue at home rehabilitation after stroke |

SAFEMOVE | The project aims to increase the mobility of the elderly, both at home and on journeys, through encouraging self-confidence in own abilities |

V-TIME | V-TIME proposes a unique rehabilitation-like training program that simultaneously targets multiple elements of fall risk and teaches individuals new strategies for fall prevention and maintenance of a healthy lifestyle in a safe and enjoyable manner |

DOREMI | To develop a solution for older people to prolong their functional and cognitive capacity by empowering, stimulating and unobtrusively monitoring their daily activities; these are monitored by professionals |

BeatHealth | Exploit the link between music and movement for boosting individual performance and enhancing health and wellness |

Inspiration | Help older adults live a healthier life and to stay mentally and physically fit. Besides a digital coach, system provides health tips and a daily planner. Recorded activities can be accessed by relatives, friends and caregivers |

PERSSILAA | Innovates the way care services are organized. From fragmented, reactive disease management into preventive, personalized services that are offered through local community services and telemedicine technology |

Wellbeing | Wellbeing offers a holistic platform, combining physical exercises, workplace ergonomics, nutritional balance, and stress management in order to ensure a healthy life at the workplace |

TRAINUTRI | To raise consciousness about self wellness, by developing healthy habits and enabling exchange of knowledge on physical and nutritional healthy habits |

ACANTO | To spur older adults into a sustainable and regular level of physical exercise under the guidance and the supervision of their carers |

MOTION | Develop an ICT-based service for remote multi-user physical training of seniors at home by specialized coaches |

Fit4Work | A system for self-management (detecting, monitoring and countering) of physical and mental fitness of older workers |

ELF@Home | Elderly self-care based on self-check of health conditions and self-fitness at home (~personal trainer at home) |

Alfred | Develop a mobile, personalized assistant for the elderly, which helps them stay independent, coordinate with carers and foster their social contacts |

PhysioDom-HDIM | To guide elder people in their health well-being and independence, providing physical activity and dietary coaching in their own home |

Florence | Improve the well-being of elderly (and their caregivers) and efficiency in care through AAL services supported by a general-purpose robot platform |

DOSSY | Develop an intelligent outdoors navigation app with high quality route information and basic safety system |

Give&Take | Strengthen the quality of life of senior citizens through occupation and social engagement as a key to mental, social and physical fitness. Also, support civic engagement and ability to live independently |

Appendix 2: Projects Characteristics

Project acronym | Specific condition? | PA main goal? | Health Improvement | Type of physical activity and specific exercises | Technology use and evidence of entertainment-related attributes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

GameUP | No | Yes | Physical | Type of PA: Aerobic, Muscle strengthening and Balance. Walking and exergames for balance, strength, and endurance that track user’s progression | System uses games. These link to stepcounter, motion sensors, camera |

AIB | Falls prevention | No | Unspecified, general health | Type of PA not specified Games using Kinect with coach who offers exercise guidance and monitors progression of the older person | Games and persuasive technologies build upon the use of Kinect. Solution is tailored to each individual and targets motivation and behavior change |

FARSEEING | Falls prevention | No | Physical | Type of PA: Muscle strengthening, Balance. Exercises in chairs, knee strengthened shoulder mobility exercise, side hip strengthened etc. | Exergames offer muscle and balance training and are used to motivate older adults to take-up and maintain exercise. Technologies used include: wearable sensors, depth camera, accelerometer, Kinect, GAITRite walkway |

IS-ACTIVE | Chronic conditions | Yes | Physical, Social | Type of PA: Aerobic, Muscle strengthening Coaching through games displayed on the TV, prepared with physical therapists collaboration | Persuasive technologies and serious games used to improve feedback and motivation, in combination with wireless sensing, pulse oximeter, tablet, smartphone |

A2E2 | No | Yes | Physical | Type of PA not specified Not specified. From descriptions seems personalised | 3D digital coach with bio-sensors including activity sensors, blood pressure and weight sensors for interaction and adaptive feedback |

Join-In | No | Yes | Physical, Social | Type of PA: Aerobic, Muscle strengthening Biking indoor exergame, walking game, video exercises | Exergames used to persuade seniors to increase physical activity through a social and gaming platform accessible via PC, TV and set-top box, or tablet. Walking exergame “AntiqueHunt” uses motion sensors |

V2me | Loneliness | Yes | Physical, Cognitive, Social | Not specified | Virtual coach |

iStoppFalls | Falls prevention | Yes | Physical | Type of PA: Balance. Stepping games, balance | TV and Kinect games with TV |

Lona-Lastina Memories | No | Yes | Physical, Cognitive | Type of PA not specified Various games, some of which using a Wii balance board | Exergaming platform to help elderly exercise and maintain physical status and well being via innovative, low-cost ICT platform, e.g. Wii Balance Board |

MOB MOTIVATOR | No | Yes | Physical, Cognitive, Social | Not specified | Tablet, multiplayer gaming environment, to increase mobility, cognitive skills, gender equality, and autonomy among older adults, both indoor and outdoor, under supervision of health professionals |

PAMAP | No | Yes | Physical | Type of PA: Aerobic, Muscle strengthening and Balance. Walking, hiking, cycling, housework, gardening | Captures almost any type of movement/ activity/ exercise and has a avatar showing how to do exercises that are linked to wearable sensor network, smartphone, kinematics, repetitive limb movements |

Rehab@Home | Stroke rehabilitation | Yes | Physical, Social | Type of PA not specified Rehabilitation exercises after stroke with serious games | Smartphones in cameras and control unit to track movement during game to collect data, online feedback from doctors, feedback, goals, achievements, sharing achievements with friends and challenging friends; Kinect |

SAFEMOVE | No | Yes | Physical, Cognitive, Social | Type of PA not specified. Seems to include all. Various serious games and monitoring activities | Serious games at home, e.g. golf, games outside, management of health by doctors, engagement, quests, personalised games |

V-T1ME | Fall prevention, Parkinson’s | Yes | Physical, Cognitive | Type of PA not specified. Treadmill | Virtual Reality treadmill and tracking with Kinect |

DOREMI | Nutrition, sedentarism, Cognitive decline | Yes -i-Nutrition, cog training | Physical, Cognitive, Social | Type of PA: Aerobic, Balance. App with serious games and exergames for daily physical activity. | Smart bracelet, smart carpet, tablet, smartphone, stepcounter, social networking, wireless sensor network, activity recognition and contextualization, behavioural pattern analysis |

BeatHealth | No | Yes | Physical | Type of PA: Aerobic. Walking and running | App leverages on entrapment and uses music and movement rhythms to promote exercise. Solution uses wearable technologies and sensors |

Inspiration | No | Yes | Physical, Cognitive | Type of PA not specified. Seems to include all. Not specified | Digital coach will motivate them to be active every day |

PERSSILAA | No | Yes. +Cognition and Nutrition, workplace ergonomics, and stress management | Physical, Cognitive | Not specified | Activity videos and game displayed through a TV. Also offers efficient, reliable, and easy to use services that make use of gamification, and |

Wellbeing | Stress | Yes +Nutrition | Physical, Cognitive | Not specified | 3D sensor, suggestions for exercises shown as exercises videos or as mini games, combining physical exercise with gaming elements. Games which are able to tackle health related problems in entertaining way |

TRAINUTRI | No | Yes +Nutrition | Physical, Social | Type of PA not specified Not specified. There are indications that is personalised | Web and smartphone apps with monitoring of activity, feedback, summaries, setup of objectives, groups, social platform |

ACANTO | No | Yes | Physical | Not specified | Robotic walking assistant with brakes that supports in execution of daily activities and require and recommends PA in compelling and rewarding way |

MOTION | No | Yes | Physical | Type of PA not specified. Seems to include all Not specified. Coach seems to design personalised activities | The service uses a high level video system allowing four simultaneous training sessions by a coach. When a user subscribes, he receives an all in one PC remotely controlled and sessions can immediately started |

Fit4Work | Stress | Yes | Physical, Cognitive | Type of PA not specified. Training participation scheme with exercises | Smartphone and watch like with sensors forming core of personal wellness network, ambient sensors, AAL middleware and cloud services |

ELF@Home | No | Yes | Physical | Type of PA not specified Personalized fitness plan offered according to health status and life style. Fitness exercises at home using a TV interface | Wearable activity sensor, biomedical sensors, personalization |

Alfred | No | No | Physical, Cognitive, Social | Type of PA not specified Walking, swimming, and app for back pain rehab and serious games to improve physical and cognitive conditions | Robot (virtual butler) used for back pain rehabilitation |

PhysioDom- HDIM | No. | Yes +Dietary advice | Physical, Social | Type of PA not specified. Possibly aerobic Not specified but use of pedometer indicates walking | Telemonitoring through medical sensors and TV, podometer, blood pressure sensors |

Florence | No | Yes | Physical, Social | Not specified | Robot with wheels, 1.5 m height, screen-based, with no arms. Sensor input based on 2D laser scanner, 3D structured light (Kinect) and camera |

DOSSY | No | Yes | Physical, Social. | Type of PA: Aerobic. Hiking. | Localization, navigation and geo-tracking |

Give&Take | No | No | Physical, Cognitive, Social | Not specified | Webpage for senior citizens to connect through to local communities and organisations for conversations, sharing, event coordination, etc. |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 IFIP International Federation for Information Processing

About this paper

Cite this paper

Silva, P.A. (2018). Physical Activity Among Older Adults: A Meta-review of EU-Funded Research Projects. In: Clua, E., Roque, L., Lugmayr, A., Tuomi, P. (eds) Entertainment Computing – ICEC 2018. ICEC 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11112. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99426-0_47

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99426-0_47

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-99425-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-99426-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)