Abstract

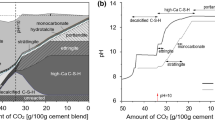

The composition of a lime-cement mortar and an air-entrained cement mortar was studied as a function of distance to the brick-mortar interface. Both mortars had the same cement-to-sand ratio and the same water-to-cement ratio; in the lime-cement mortar the binder-to-sand ratio was highest. The measurements indicate that the mortar composition (i.e. the contents of sand, cured binder and voids) and the contents of chemical substances of the cured binder (i.e. the contents of calcite, portlandite and ettringite) change with distance to the brick-mortar interface. For the mortar composition the tendency of these changes is the same, but for the contents of the chemical substances of cured binder for the two mortar types the tendency of these changes is opposite and also the extent of the changes is significantly different. For the air-entrained cement mortar, the observations are explained by the enrichment of binder towards the brick-mortar interface, resulting from the compaction of fresh mortar. In the lime-cement mortar such an enrichment of binder hardly occurs and the observations are explained by the intense carbonation that takes place. As a result, the contents of the chemical substances in the mortars is very much different. In the air-entrained cement mortar, near the brick-mortar interface the enrichment of cement and the low water content (resulting from the low water retentivity of this mortar), lower the water-to-cement ratio and as a consequence the cement is not fully hydrated. In the lime-cement mortar, as the Ca(OH)2 content and the water content is higher, near the brick-mortar interface, a carbonated zone is formed which is hardly permeable for CO2 (and probably water). This does not occur in the air-entrained cement mortar, it remains permeable.

Résumé

La composition d’un mortier de ciment et de chaux et d’un mortier de ciment à air entraîné a été examinée en fonction de la distance par rapport à l’interface brique-mortier. Les rapports ciment-sable et eau-ciment étaient identiques pour les deux mortiers. Le rapport liant-sable était le plus élevé dans le mortier de ciment et de chaux. Les mesures indiquent que la composition du mortier (teneurs en sable, liant durci et vides) et les teneurs en produits chimiques du liant durci (teneurs en calcite, portlandite et ettringite) changent en fonction de la distance par rapport à l’interface brique-mortier. Pour la composition du mortier, la tendance de ces changements est identique, par contre, en ce qui conceme les teneurs en produits chimiques du liant durci, la tendance de ces changements est opposée pour les deux types de mortier; en outre, le degré de ces changements diffère de manière significative. Pour le mortier de ciment à air entraîné, ces observations s’expliquent par un enrichissement en liant à l’interface brique-mortier, résultant du compactage du mortier frais. Comme dans le mortier de ciment et de chaux, cet enrichissement en liant se rencontre peu, les observations s’expliquent par une carbonatation importante. Par conséquent, les teneurs en produits chimiques sont très différentes dans les mortiers. Dans le mortier de ciment à air entraîné, près de l’interface brique-mortier, l’enrichissement en ciment et la faible teneur en eau (due à la faible rétention d’eau de ce mortier), diminuent le rapport eau-ciment avec pour conséquence que le ciment n’est pas hydraté complètement. Comme les teneurs en Ca(OH)2 et en eau sont plus élevées dans le mortier de ciment et de chaux, une zone carbonatée se forme près de l’interface brique-mortier qui présente une faible perméabilité au CO2 (et probablement à l’eau). Ceci ne se présente pas dans le mortier de ciment à air entraîné qui reste perméable.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brocken, H. J. P., ‘Moisture transport in brick masonry: The grey area between bricks’ (Ph.D. thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands, 1998).

Neville, A. M., ‘Properties of Concrete’, 4th ed. (Longman, London, 1995).

Taylor, H. F. W., ‘Cement Chemistry’, 2nd ed. (Thomas Telford, London, 1997).

CUR-Report 73, ‘Carbonatatic lichtbeton. Literatuurstudie (Carbonation of ligthweight concrete. Literature study)’ (CUR-Institute, Gouda, The Netherlands, 1975) 9–19.

Larbi, J. A., ‘The cement paste aggregate interfacial zone, (Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands, 1991).

Balen, K. van and Gemert, D. van, ‘Modelling lime mortar carbonation’,Mater. Struct. 27 (1994) 393–398.

Kuzel, H. J. and Pöllmann, H., ‘Hydration of C3A in the presence of Ca(OH)2, CaSO4·2H2O and CaCO3’,Cem. Con. Res. 21 (1991) 885–895.

Kuzel, H. J., ‘Initial reactions and mechanisms of delayed ettringite formation in portland cement’,Cem. Con. Compos. 18 (1996) 195–203.

Nishikawa, T., Suzuki, K. and Ito, S., ‘Decomposition of synthesized ettringite by carbonation’,Cem. Con. Res. 22 (1992) 6–14.

Kopinga, K. and Pel, L., ‘One-dimensional scanning of moisture in porous materials with NMR’,Rev. Sci. Instrum. 65 (1994) 3673–3681.

Brocken, H. J. P., Spiekman, M. E., Pel, L., Kopinga, K. and Larbi, J. A., ‘Water extraction out of mortar during brick laying: a NMR study’,Mater. Struct. 31 (1998) 49–57.

Klug, H. P. and Alexander, L. E., ‘X-Ray Diffraction Procedures’, 2nd ed. (Wiley, New York, 1974) 505.

International Centre for Diffraction Data (12 Campus Boulevard, Newton Square, PA 19073-3273, U.S.A).

Bousfield, B., ‘Surface preparation and microscopy of materials’, 1st ed. (Wiley, Chicester, 1992) 291.

French, W. J., ‘Concrete petrography: a review’,Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology 24 (1991) 17–48.

Larbi, J. A. and Bijen, J. M., ‘Effects of water-cement ratio, quantity and fineness of sand on the evolution of lime in set portland cement systems’,Cem. Con. Res. 20 (1990) 783–794.

Kollmann, H., Strübel, G. and Trost, F., ‘Reaction mechanisms in the formation of expansion nuclei in lime-gypsum plasters by ettringite and thaumasite’,Zement-Kalk-Gips 5 (1977) 224–229.

Sugo, H. O., Page, A. W. and Lawrence, S. J., ‘Influence of the macro & microstructure of air entrained mortars on masonry bond strength’ (Proceedings of the 7th N. Am. Mas. Conf., 1996) 230–241.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Editorial Note TNO Building and Construction Research and Delft University of Technology are RILEM Titular Members.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brocken, H.J.P., van der Pers, N.M. & Larbi, J.A. Composition of lime-cement and air-entrained cement mortar as a function of distance to the brick-mortar interface: consequences for masonry. Mat. Struct. 33, 634–646 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02480603

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02480603