Abstract

Background

Studies conducted in the UK and in Ireland have reported increased rates of self-harm in adolescent females from around the time of the 2008 economic recession and through periods of subsequent national austerity programme implementation. It is not known if incidence rates have increased similarly in other Western European countries during this period.

Methods

Data from interlinked national administrative registers were extracted for individuals born in Denmark during 1981–2006. We estimated gender- and age-specific incidence rates (IRs) per 10,000 person-years at risk for hospital-treated non-fatal self-harm during 2000–2016 at ages 10–19 years.

Results

Incidence of self-harm peaked in 2007 (IR 25.1) and then decreased consistently year on year to 13.8 in 2016. This pattern was found in all age groups, in both males and females and in each parental income tertile. During the last 6 years of the observation period, 2011–2016, girls aged 13–16 had the highest incidence rates whereas, among boys, incidence was highest among 17–19 year olds throughout.

Conclusions

The temporal increases in incidence rates of self-harm among adolescents observed in some Western European countries experiencing major economic recession were not observed in Denmark. Restrictions to sales of analgesics, access to dedicated suicide prevention clinics, higher levels of social spending and a stronger welfare system may have protected potentially vulnerable adolescents from the increases seen in other countries. A better understanding of the specific mechanisms behind the temporal patterns in self-harm incidence in Denmark is needed to help inform suicide prevention in other nations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescents who have self-harmed have a markedly increased risk of suicide compared to their peers [1], with suicide being the second most common cause of death in this age group [2, 3]. Risk of all-cause mortality is also markedly higher [4]. Rates of hospital-treated self-harm have been found to be particularly raised in adolescents compared to older age groups. Studies examining emergency department (ED) visits in Western countries (including Ireland, the US, Denmark and the UK) have found the highest rates of self-harm among girls aged between 15 and 19 years [5,6,7,8,9]. A substantial body of evidence indicates that economic recession and its aftermath is associated with increases in rates of suicide and self-harm, though much of this work focuses on the working-age population [10,11,12]. Evidence from a study of ED presentations in Ireland [5] and also from a primary care patient cohort in the UK [13] indicate that self-harm incidence rates among adolescent females increased from around the time of the 2008 economic recession and through the era of subsequent austerity measures. Similarly, rates of ED presentation following self-harm and mental health concerns both increased rapidly among adolescents between 2009 and 2017 in Ontario, Canada, with particularly pronounced increases seen in girls [14]. Comparing temporal trends in mental health between countries is an important step in understanding possible risk and protective factors at population level [15]. In Denmark, increasing rates of self-harm in females aged 15–19 between 1994 and 2011 [9] and from 1994 to 2003 in girls (and, to a lesser extent, boys) aged 10–16 [16] have been reported. However, it has yet to be determined if these trends continued into recent years.

Poisonings are the most common method of hospital-presenting self-harm in the UK, Ireland and Denmark [5, 7, 9], but self-injury is the more common type of self-harm in the community [7]. A recently published study examined prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in England, regardless as to whether treatment was sought [17]. The greatest increase in prevalence was among females aged 16–24 years and, in particular, the proportion using self-harm to manage unpleasant feelings rose in females but not males between 2007 and 2014. In Denmark, parental unemployment has been linked to increased risks of suicidal behaviour in young people, although neglect, abuse and substance misuse and other mental disorders appeared to be stronger predictors [18]. The combination of factors involved in the temporal patterns of adolescent self-harm remains unclear.

In the present study we examined temporal trends in hospital-treated self-harm during years 2000–2016 among young people aged 10–19 living in Denmark. We also explored trends according to sex, age and parental income, and examined differences between these groups.

Method

Data from interlinked national administrative registers were extracted for all individuals born in Denmark between 1st January 1981 and 31st December 2006. Cohort members were alive and residing in the country on their 10th birthday, after which they were considered to be at risk of self-harm. The population was restricted to individuals alive at the beginning of follow-up, with first self-harm episode recorded between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2016 being the outcome of interest. Individuals who died or emigrated from Denmark before the end of follow-up were censored at date of death or emigration.

We included self-harm episodes that were treated in EDs or in psychiatric outpatient clinics and those that resulted in admission to general hospitals or psychiatric units. Episodes were identified from the National Patient Register [19] and the Psychiatric Central Research Register [20] by applying a previously derived coding algorithm [21]. This definition of ‘self-harm’ included presentations recorded as ‘intentional self-harm’ (ICD-10 codes X60–X84), those recorded as a psychiatric diagnosis with either comorbid non-fatal self-poisoning (including drugs and biological substances in ICD-10 codes T36–T50 and non-medical compounds excluding food and alcohol poisoning in T52–T60) or self-injury (ICD-10 codes S51, S55, S59, S61, S65, or S69) and poisoning with specific drugs (see Nordentoft et al. [21] for the complete algorithm). In addition, ‘reason for contact’ code 4 (‘deliberate self-harm’) used nationally in Danish hospitals was applied to identify episodes of self-harm. While different procedures have been used over time to identify self-harm cases in the Danish registers, no such changes occurred during this study’s 2000–2016 observation period. This definition is essentially congruent with that used in other European countries [10, 21,22,23].

We estimated self-harm incidence rates among adolescents aged 10–19 years, in line with the World Health Organization’s definition of adolescence [24]. We examined incidence separately in the following age groups: pre-teenager (10–12 years), younger teenager (13–16) and older teenager (17–19). We calculated annual incidence rates per 10,000 person-years, stratified by age, sex and parental income tertile. In addition, we calculated the gender-specific incidence rates for the final 3-year time period (2014–2016 combined) by age (13–16 and 17–19) and parental income levels. In this analysis, we did not include the 10–12 age group due to insufficient numbers with self-harm by subgroup. We also reported the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) comparing incidence rates of girls vs. boys stratified by age and income level. Analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15 [25]. This study followed STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies [26].

As this study was conducted exclusively using interlinked registry data informed consent from persons in the study population was not required, in accordance with the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data, Section 10.

Results

Description of the study cohort

There were 1,710,167 individuals born in Denmark between 1st January 1981 and 31st December 2006 who were alive at the beginning of follow-up and residing in Denmark on their 10th birthday. Of these, 26,950 persons were identified as having a first recorded self-harm episode during the 2000–2016 study period which included 14,111,718 person-years; 19,185 (71.2%) were girls and 7765 (28.8%) were boys.

Self-harm incidence rates

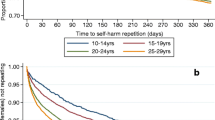

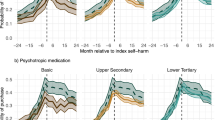

The incidence rate of self-harm among all adolescents aged 10–19 years peaked in 2007 (IR 25.1) then decreased consistently year on year to 13.8 in 2016. This pattern of falling incidence was found in both males and females, although the incidence rate among males was 30–40% of the rate for females (Fig. 1). Among boys, rates were highest at 17–19 years of age (Fig. 2b). Younger teenage girls (aged 13–16) had the highest rate across the final 6 years of the observation period (Fig. 2a). The largest difference in self-harm rates between boys and girls was seen in the 13–16 age group (2014–2016 3-year IRR 5.8; 95% CI 5.1, 6.7). Sex differences were similar across parental income groups (Table 1). Adolescents living in households with high parental income had lower rates of self-harm in each year of observation. Incidence rates over the 2000–2016 study period were highest among those in the lowest parental income group (Fig. 3a–c). The increase and subsequent decrease observed in the whole national population was also seen within each parental income tertile, but was most marked in the lowest tertile (2007 IR 40.6; 95% CI 38.0, 43.3 vs. 2016 IR 21.6; 95% CI 19.4, 24.0).

a Temporal trends in annual incidence of self-harm by sex (3-year moving averages): lowest parental income tertile. b Temporal trends in annual incidence of self-harm by sex (3-year moving averages): mid-parental income tertile. c Temporal trends in annual incidence of self-harm by sex (3-year moving averages): highest parental income tertile

Discussion

Main findings

For both adolescent boys and girls, the national self-harm incidence rate increased gradually from 2000 to a peak in 2007, then from 2008 to 2016 it decreased to just below the rate observed at the start of the study period. Incidence was highest among girls aged 13–16 and adolescents in the lowest parental income group. Overall fluctuations in self-harm incidence followed the same pattern within each parental income tertile.

Interpretation and comparison with existing evidence

In 2008 non-opioid analgesics became available over the counter in Denmark, and in 2011 an age restriction was introduced for those aged under 18 years buying analgesics of this type. In 2013 a pack size restriction was introduced, with larger pack sizes requiring a prescription. There is evidence that decreases in rates of adolescents self-poisoning accounts for some of the overall decline in self-harm incidence seen between 2010 and 2014 [27]. However, self-cutting, attempted hanging and other methods of self-harm also decreased between 2008 and 2016 [27].

In the UK and Ireland, increases in rates of self-harm and suicide in young people have been attributed, at least partially, to the economic recession in 2008 followed by a sustained period of national governmental austerity measures [10]. Societies that expect individuals to be solely responsible for their own prosperity during economic crises and austerity policies can marginalise those who do not thrive. For individuals experiencing unemployment and loss of social status, emotions associated with suicidal behaviour, such as shame, defeat and entrapment can be exacerbated [28]. Higher rates of self-harm and suicide have been found for adolescents growing up in families of lower socioeconomic position [6, 13, 29, 30], even following psychiatric treatment [30]. Whilst we also observed higher rates of self-harm among lower household income groups, rates decreased from 2008 in all three parental income tertiles. This suggests that the phenomena associated with reductions in self-harm incidence had a similar impact across all income groups. Danish welfare systems and other national policies may have compensated for income-based differences in self-harm rates. Data from Europe and the US have indicated that when adequate policies are implemented to protect populations from the detrimental effects of rises in unemployment, harmful impact on mental health can be mitigated [31, 32]. Our findings suggest that these effects apply to non-working age adolescents as well as adults. However, the higher rates, despite the observed temporal decreases, suggest unmet need remains among young people from lower income households.

In Ireland, increases in ED self-harm rates between 2007 and 2016 were particularly pronounced among girls aged 10–19 [5]. Similarly, in the UK, self-harm incidence rates in GP-registered patient cohort increased only in younger teenage girls aged 13–16, with this group also having the highest rates of all age and sex groups [13]. We also found this age group to have the highest rate of self-harm in Denmark. It is not clearly understood why younger teenage girls face such increased levels of psychological distress. Plausibly, they may be more vulnerable to certain negative aspects of social media that could have a harmful psychological impact [33]. However, there is evidence that young people may gain support for their mental health problems online [34]. There is also thought to be a higher level of help-seeking in general among teenage girls, which may explain part of the gap in hospital-treated rates between boys and girls [13].

Denmark offers a psychosocial therapy for people at risk of suicide, which was gradually introduced in 1992 and became available nationally in 2007 [35]. Individuals can be referred to this service following an episode of self-harm or suicide ideation. The service appears to be effective at reducing future self-harm and suicide, particularly among adolescents and young adults [35]. Evidence from the UK has shown that adolescents from the most socially deprived areas had higher rates of self-harm, but were least likely to receive specialist mental health follow-up care following self-harm [13]. Consistent availability of psychosocial treatment, specially designed for suicide prevention, may have helped to reduce self-harm rates among young people in Denmark.

A number of studies have found increasing rates of mood disorders over recent years among young people living in Western countries [33, 36]. Incidence of self-harm is likely to be strongly linked with incidence of depression, although we did not have access to information on mental disorders across the severity spectrum at population level among young people in Denmark. Finally, interpretation of temporal patterns depends on the starting point. A previous study of self-harm rates in Denmark, using a different algorithm to define self-harm, found an increase between 1994 and 2011 [9], particularly among females aged 15–24. The decrease from 2008 onwards observed in the present study resulted in the rate of self-harm returning to the 1994 rate [9].

Strengths and limitations

Few countries have registry data available for estimating national incidence rates of self-harm. The use of interlinked Danish registers enabled us to capture episodes treated by emergency departments, outpatient clinics and psychiatric units. However, we could not include self-harm by individuals who did not present to hospital. Our findings, therefore, may not be applicable to self-harm where adolescents present to primary care, or do not seek help from health services at all. Furthermore, the rarity of suicide compared to self-harm precluded us from discerning temporal patterns. Therefore, it is not known if suicide rates followed similar patterns to self-harm.

While similar definitions of self-harm are used in Denmark and England, the sources of data, data collection procedures and exact inclusion/exclusion criteria differ. Although there are standardised procedures for recording self-harm in Danish registers, there may be some under-recording nonetheless [9]. However, there is no known reason that the degree of under-recording would change by year, as there were no changes in the procedures used to identify self-harm episodes during the study’s observation period, therefore temporal trends should not be affected. Finally, for this study we could not examine method of self-harm or the substances used in self-poisonings.

Conclusions

Restrictions on analgesic sales may explain some of the decrease in incidence of adolescent self-harm that were observed during the study period. It is also important to understand broader societal measures that may have contributed to decreases in self-harm incidence, particularly those that protect populations following economic recession. Denmark’s Suicide Prevention Clinics have been shown to effectively reduce self-harm. While rates of self-harm were highest among mid-teenage girls, it is notable that the increase in self-harm incidence among this group that has been reported elsewhere was not apparent in Denmark. While there is strong evidence for the harmful effects of economic recession on rates of self-harm and suicide among working-age populations, relatively little is known about protective effects among adolescents, particularly girls. Such evidence could have important policy and health implications.

References

Hawton K, Bergen H, Kapur N, Cooper J, Steeg S, Ness J, Waters K (2012) Repetition of self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-Harm in England. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(12):1212–1219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02559.x

Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, Vos T, Ferguson J, Mathers CD (2009) Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 374(9693):881–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60741-8

World Health Organization (2014) Preventing suicide: a global imperative. WHO, Geneva

Hawton K, Harriss L (2007) Deliberate self-harm in young people: characteristics and subsequent mortality in a 20-year cohort of patients presenting to hospital. J Clin Psychiatry 68(10):1574–1583. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v68n1017

Griffin E, McMahon E, McNicholas F, Corcoran P, Perry IJ, Arensman E (2018) Increasing rates of self-harm among children, adolescents and young adults: a 10-year national registry study 2007–2016. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53(7):663–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1522-1

Canner JK, Giuliano K, Selvarajah S, Hammond ER, Schneider EB (2018) Emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self harm in the USA: 2006–2013. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 27(1):94–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796016000871

Geulayov G, Casey D, McDonald KC, Foster P, Pritchard K, Wells C, Clements C, Kapur N, Ness J, Waters K, Hawton K (2018) Incidence of suicide, hospital-presenting non-fatal self-harm, and community-occurring non-fatal self-harm in adolescents in England (the iceberg model of self-harm): a retrospective study. Lancet Psychiatry 5(2):167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30478-9

Mok PLH, Antonsen S, Pedersen CB, Appleby L, Shaw J, Webb RT (2015) National cohort study of absolute risk and age-specific incidence of multiple adverse outcomes between adolescence and early middle age. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2249-5

Reuter Morthorst B, Soegaard B, Nordentoft M, Erlangsen A (2016) Incidence rates of deliberate self-harm in Denmark 1994–2011. Crisis 37(4):256–264

Corcoran P, Griffin E, Arensman E, Fitzgerald AP, Perry IJ (2015) Impact of the economic recession and subsequent austerity on suicide and self-harm in Ireland: an interrupted time series analysis. Int J Epidemiol 44(3):969–977. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv058

Alicandro G, Malvezzi M, Gallus S, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Bertuccio P (2019) Worldwide trends in suicide mortality from 1990 to 2015 with a focus on the global recession time frame. Int J Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01219-y

Alexopoulos EC, Kavalidou K, Messolora F (2019) Suicide mortality patterns in Greek work force before and during the economic crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(3):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030469

Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, Kontopantelis E, Green J, Chew-Graham CA, Kapur N, Ashcroft DM (2017) Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. Bmj. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4351

Gardner W, Pajer K, Cloutier P, Zemek R, Currie L, Hatcher S, Colman I, Bell D, Gray C, Cappelli M, Duque DR, Lima I (2019) Changing rates of self-harm and mental disorders by sex in youths presenting to Ontario emergency Departments: repeated cross-sectional study. Can J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719854070

Gunnell D, Kidger J, Elvidge H (2018) Adolescent mental health in crisis. Bmj. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2608

Christiansen E, Larsen KJ, Agerbo E, Bilenberg N, Stenager E (2013) Incidence and risk factors for suicide attempts in a general population of young people: a Danish register-based study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 47(3):259–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412463737

McManus S, Gunnell D, Cooper C, Bebbington PE, Howard LM, Brugha T, Jenkins R, Hassiotis A, Weich S, Appleby L (2019) Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–2014: repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. Lancet Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30188-9

Christoffersen MN, Poulsen HD, Nielsen A (2003) Attempted suicide among young people: risk factors in a prospective register based study of Danish children born in 1966. Acta Psychiatr Scand 108(5):350–358. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00165.x

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M (2011) The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health 39:30–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811401482

Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB (2011) The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health 39:54–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810395825

Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB (2011) Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68(10):1058–1064

Sahlin H, Kuja-Halkola R, Bjureberg J, Lichtenstein P, Molero Y, Rydell M, Hedman E, Runeson B, Jokinen J, Ljotsson B, Hellner C (2017) Association between deliberate self-harm and violent criminality. Jama Psychiatry 74(6):615–621. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0338

Kapur N, Cooper J, O’Connor RC, Hawton K (2013) Non-suicidal self-injury v. attempted suicide: new diagnosis or false dichotomy? Br J Psychiatry 202(5):326–328. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116111

World Health Organization (2018) Adolescent mental health. https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/adolescent/en/. Accessed 24 Mar 2019

StataCorp (2017) Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC, College Station

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S (2008) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61(4):344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Erlangsen A (2019) Rater for Selvmord og Selvmordsforsøg. DRISP. http://drisp.dk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Rater-for-Selvmord-og-Selvmordsforsøg_Jan_2019-1.pdf. Accessed 04 Jun 2019

Chandler A (2019) Socioeconomic inequalities of suicide: sociological and psychological intersections. Eur J Soc Theory. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431018804154

Lodebo BT, Moller J, Larsson J-O, Engstrom K (2017) Socioeconomic position and self-harm among adolescents: a population-based cohort study in Stockholm, Sweden. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0184-1

Christiansen E, Larsen KJ (2012) Young people’s risk of suicide attempts after contact with a psychiatric department—a nested case-control design using Danish register data. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(1):16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02405.x

Zimmerman SL (2002) States’ spending for public welfare and their suicide rates, 1960 to 1995: what is the problem? J Nerv Ment Dis 190(6):349–360. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000018958.17287.cf

Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A, McKee M (2009) The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 374(9686):315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61124-7

Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN (2018) Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci 6(1):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617723376

Marchant A, Hawton K, Stewart A, Montgomery P, Singaravelu V, Lloyd K, Purdy N, Daine K, John A (2017) A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: the good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181722

Erlangsen A, Lind BD, Stuart EA, Qin P, Stenager E, Larsen KJ, Wang AG, Hvid M, Nielsen AC, Pedersen CM, Winsløv J, Langhoff C, Mühlmann C, Nordentoft M (2014) Short-term and long-term effects of psychosocial therapy for people after deliberate self-harm: a register-based, nationwide multicentre study using propensity score matching. Lancet Psychiatry 2:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00083-2

Gyllenberg D, Marttila M, Sund R, Jokiranta-Olkoniemi E, Sourander A, Gissler M, Ristikari T (2018) Temporal changes in the incidence of treated psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders during adolescence: an analysis of two national Finnish birth cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry 5(3):227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30038-5

Funding

The funding was received by H2020 European Research Council (Grant no. Starting Grant (StG), LS7, ERC-2013-StG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Steeg, S., Carr, M.J., Mok, P.L.H. et al. Temporal trends in incidence of hospital-treated self-harm among adolescents in Denmark: national register-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 415–421 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01794-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01794-8