Abstract

WC-Co hardmetals are widely used in wear-resistant parts, cutting tools, molds, and mining parts, owing to the combination of high hardness and high toughness. WC-Co hardmetal parts are usually produced by casting and powder metallurgy, which cannot manufacture parts with complex geometries and often require post-processing such as machining. Additive manufacturing (AM) technologies are able to fabricate parts with high geometric complexity and reduce post-processing. Therefore, additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals has been widely studied in recent years. In this article, the current status of additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals is reviewed. The advantages and disadvantages of different AM processes used for producing WC-Co parts, including selective laser melting (SLM), selective electron beam melting (SEBM), binder jet additive manufacturing (BJAM), 3D gel-printing (3DGP), and fused filament fabrication (FFF) are discussed. The studies on microstructures, defects, and mechanical properties of WC-Co parts manufactured by different AM processes are reviewed. Finally, the remaining challenges in additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals are pointed out and suggestions on future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Hardmetals, typically consisting of a carbide skeleton and metal binder, are a group of materials having extraordinary hardness and wear-resistance and highly desirable in some demanding environments [1,2,3]. Among them, tungsten carbide-cobalt (WC-Co) is one of the most widely used materials for wear-resistant parts, cutting tools, molds, mining part for excavation, and electronic packaging since its advent in 1923 thanks to its excellent performance [4, 5]. WC-Co cermet with a Co content of 5–25 wt.% possesses superior hardness, compressive strength, fracture toughness, and transverse rupture strength [6, 7]. In addition, WC-Co provides high wear properties and good corrosion resistance [8,9,10,11,12]. Binder content, carbide particle size, and carbide particle distribution are critical factors affecting the mechanical properties of the WC-Co cermet [13,14,15,16]. It was identified that the increase in wear resistance has a linear relationship with the reduction of the square root of WC particle size regardless of the Co contents [15]. The relationship between hardness of WC-Co samples and WC distance size and Co content is shown in Fig. 1 [17].

WC-Co could be produced through conventional molding methods including injection molding, extrusion molding, and powder metallurgy. The component produced by injection molding has a small shrinkage, but a high susceptibility to form undesirable η phase (Co3W3C, Co6W6C, etc.) [18,19,20,21]. Extrusion and powder metallurgy can achieve low porosity, but these processes can only produce components with limited geometrical complexity [22,23,24,25,26,27]. In addition, these conventional processes are inefficient and costly [28].

Additive manufacturing (AM) process has emerged as an alternative to traditional manufacturing processes that can fabricate very complicated geometries with high efficiency and low cost [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Therefore, more and more attention have been paid to additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals. Unlike the traditional processes, AM technologies manufacture parts by adding materials layer by layer, which increases the complexity of part geometry and reduces time and cost [36,37,38]. Additive manufacturing technologies offer attractive advantages in terms of producing WC-Co hardmetal cutting tools with complex geometries, such as U-shaped or helical cooling channels inside. These internal, contour-adapted cooling channels allow higher cutting speeds and, consequently, a remarkable increase in the productivity of the machining process. The main additive manufacturing technologies suitable for metals are selective laser melting (SLM), selective electron beam melting (SEBM), laser powder deposition, binder jet additive manufacturing (BJAM), and wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. So far, AM technologies have been successfully applied to stainless steels [50,51,52,53,54], Ni alloys [55, 56], Ti alloys [57, 58], refractory metals [59, 60], Al alloys [61, 62], etc. For tungsten carbide-cobalt, it still remains very challenging to use AM due to its very high melting temperature. SLM and BJAM are the most attempted AM processes for manufacturing WC-Co hardmetals. Besides, a few studies on SEBM [41], 3D gel-printing (3DGP) [63], and fused filament fabrication (FFF) [64] of WC-Co hardmetal samples were reported. The AM techniques used for fabrication of WC-Co hardmetals and the main research groups working on WC-Co AM were summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Although some examples of WC-Co parts with nearly full density and good mechanical properties have been successfully manufactured by AM technologies [65, 78], there are still many problems to be resolved. Insufficient mechanical properties still prevent applying the new process in industry [92,93,94]. The almost unavoidable defects, such as micro-cracks and porosities, and lack of dimensional accuracy, prevent AM processes from being widely used for producing WC-Co parts in industry [67, 95]. Post-processings, such as heat treatment, hot isostatic pressing (HIP), infiltration, and machining, are often required, resulting in additional time and cost [96, 97].

In this review, the current status of additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals is reviewed. The advantages and disadvantages of different AM processes used for producing WC-Co parts, including selective laser melting, binder jet additive manufacturing, selective electron beam melting, 3D gel-printing, and fused-filament fabrication are discussed. The studies on microstructures, defects, and mechanical properties of WC-Co parts manufactured by different AM processes are reviewed. Finally, the remaining issues and suggestions on future research on additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals are put forward.

2 Additive manufacturing processes used for WC-Co hardmetals

Additive manufacturing processes used for fabrication of WC-Co hardmetals include the following: (1) selective laser melting (SLM, also called laser powder bed fusion, L-PBF), (2) selective electron beam melting (SEBM, also called electron beam powder bed fusion, E-PBF), (3) binder jet additive manufacturing (BJAM), (4) 3D gel-printing (3DGP), and (5) fused filament fabrication (FFF), as summarized in Table 2.

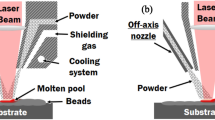

2.1 SLM and SEBM

SLM is currently the most promising AM technology for metal materials, which selectively melts powder layer by layer with a laser beam (as illustrated in Fig. 2) to form dense parts with good mechanical properties comparable to casting or forging [98, 99]. Subsequently, post-processing is sometimes essential for SLM due to the need to reduce defects and eliminate residual stress [100,101,102].

SEBM is similar to SLM, but also different in some aspects. For metal AM, SLM is more widely used than SEBM mainly due to lower equipment cost. SEBM can only be used for conductive materials since electric conductivity is required [84]. The most important difference is the heat sources. The heat source of the SEBM is an electron beam, which can be controlled by a magnetic field and causes the scanning speed to be much higher than the SLM [41]. The use of an electron beam leads to the need for a vacuum, whereas SLM requires only argon protection [84]. This also makes the cavity volume of SLM larger than SEBM. The heat source also determines how heat is absorbed by the material. Laser is absorbed or reflected within a few nanometers of the material’s surface, while electron beam can reach a depth of a few microns, which is about three orders of magnitude larger [85]. In addition, the operating temperature of SEBM is higher than SLM [86]. Usually, supporting structure is much less required for SEBM compared with SLM, since there is a heating (sintering) step for SEBM, in which the sintered powder acts as a kind of support structure [84]. As a result, the geometric freedom of SLM is lower than SEBM.

For the AM technology that uses a heat source to melt powder, energy density is a very important parameter and related to many properties of the sample [103]. Energy density is defined as:

where P is the power of laser/electron beam (W), v is the scanning speed of the beam (mm/s), h is the spacing of the scanning lines (mm), and l is the thickness of the powder layer (mm) [103,104,105].

BJAM

BJAM is an additive manufacturing technique in which the powders are bound together selectively by a liquid binding material and sintered thereafter to form a high strength part as shown in Fig. 3 [106,107,108]. In BJAM process, thin metal powder layers are distributed on the substrate and selectively bound by liquid binders sequentially (instead of melted by a heat source) to obtain a so-called green part, which has a weak strength but strong enough to maintain the 3D shape during handling. Next, a debinding step is carried out to remove the polymer binder material followed by a sintering process to form a strong metal part [78, 79]. For WC-Co, the sintering temperature is usually higher than 1400 °C. Parts fabricated through BJAM often has high level of porosities due to the nature of sintering, i.e., partially melting of the powder, and sometimes can be infiltrated by another metal, if needed. For WC-Co, tungsten carbide skeleton can be fabricated first through the BJAM process and infiltrated with Co [76, 77]. In this way, infiltrating Co content needs to be carefully calculated, which means that the Co content in the sample cannot be controlled exactly [76].

Compared to SLM, BJAM is a cost-effective process, although it typically consists of three steps [87]. Shrinkage occurs unavoidably during the sintering process of the BJAM and therefore needs to be compensated during the design stage, which means that the dimensional accuracy cannot be controlled precisely [76,77,78]. For SLM, due to the extremely high cooling rates and thermal cycle, the sample produced by SLM has an uneven microstructure with high residual stress, and is very prone to form defects such as porosities and micro-cracks [75, 100, 109].

For the AM processes that require a powder spreading step, including the above three, powder properties, most importantly the flowability, are critical to the success [110]. In SLM and BJAM without an infiltration process, WC-Co powders need to be pre-alloyed before printing [78, 111]. In the BJAM process that requires infiltration, WC powder is used directly [76]. Regardless of whether it is WC-Co powder or WC powder, the particle size will affect the fluidity, and 10 to 50 μm is a suitable size [78, 111]. The powder should be spherical and free of surface defects because the irregular topography and defects can impair the flowability of the powder [112]. In addition, the powder needs to have low residual moisture which can cause porosity at high temperatures [103]. Spray drying and cold pressing and crushing are two typical WC-Co powder preparation processes. Because the WC-Co powder made by the crushing and sintering method is irregular, spray drying is a more suitable process [41, 72].

2.2 3D gel-printing

3DGP is an additive manufacturing technique that combines gel casting and fused deposition modeling (FDM) [63, 89]. In the 3DGP process, the powder is first dissolved in an organic solvent to form a slurry. During the printing process, the slurry is added to the screw extruder together with the initiator and catalyst by compressed air. These materials are mixed and extruded from a nozzle and deposited on a printing platform as shown in Fig. 4. The nozzle is selectively moved to ensure that the required shape is printed. Organic matter is cross-linked and polymerized to fix the powder to form a green part. Subsequently, debonding and sintering processes are performed to obtain a finished sample [63]. Unlike the above technology, 3DGP does not spread powder on the powder bed, which means that the powder is not required to have high fluidity. It also means no raw material loss [63, 88].

2.3 Fused filament fabrication

FFF is an additive manufacturing technology similar to 3DGP. But different from using powder slurry as the printing material, FFF technology uses powder to prepare filament as the printing material [90]. The preparation of filament is an important step in the FFF process. A main binder and a backbone are mixed with the powder firstly. Then, a high-pressure capillary rheometer is used to prepare filament by extrusion. The printing process is shown in Fig. 5. The filament is output from the nozzle and selectively deposited on a printing platform to form a green part. Subsequently, a debonding process and a sintering process are performed [91]. Unlike debonding processes in the above additive manufacturing, a solvent debonding in which the green part is placed in organic solvents is performed before thermal debonding [64].

In summary, the above five additive manufacturing processes can be divided into two types: selective melting process and shaping-debonding-sintering (SDS) process. Selective melting processes include SLM and SEBM, which make parts by melting powder with a heat source. This type of process is very simple and enables one-step molding. But sometimes post-processing is needed to eliminate stress and defects. The SDS process includes BJAM, 3DGP, and FFF. The SDS type processes are characterized by forming a green part with organic compounds as binder and then sintering. Compared with the selective melting process, the SDS process is more complicated. Because SLM, SEBM, and BJAM all contain a powder spreading step, all three processes require the powder to have good flowability. While 3DGP and FFF prepare powders as slurry and filament for printing, there is no need for powder flowability. The application of SEBM is limited by its very high equipment cost. SLM suffers from uneven microstructure, carbon loss, and evaporation of Co. More details on advantages and disadvantages of various AM processes used for WC-Co are summarized in Table 2.

3 Macroscopic characteristics of samples

SLM WC-Co samples have almost no macro defects when an appropriate scanning strategy and parameters are used, but the surface of the sample is very rough as shown in Fig. 6 [70, 72]. When the scanning area occupies a small portion of a single layer, the melted material suffers a very severe thermal impact leading to a high tendency of macro defects [73]. Figure 7 shows WC-Co samples prepared by SEBM. The surface of the sample prepared by SEBM is a bit rough. Samples prepared by SEBM usually have macroscopically visible pores that can be eliminated by sintering [41]. Porosity in SLM samples can also be eliminated by HIP (hot isostatic pressing) due to the rearrangement and diffusion of particles when the energy density is not too low to cause a large number of porosities [114].

In the BJAM process, significant shrinkage of the printed WC-Co parts occurred due to the densification and removal of the binder. In simple cuboid samples, the shrinkage can reach 22–27% as shown in Fig. 8 [79]. In samples with complex geometries, this shrinkage is anisotropic. The shrinkage in the x and y directions is about 6–9%, while the shrinkage in the z direction can reach 21–23%. As the height increases, the shrinkage in the x and y directions also increases. It may be that the weight of the part has increased too much during the infiltration process and slump under its own weight [77]. In addition, unsintered samples cannot retain their original shape during infiltration [76].

The macro morphology of the 3DGP WC-Co hardmetal sample is shown in Fig. 9. The morphology of 3DGP samples is mainly affected by the filling rate and nozzle diameter. Due to the extrusion swelling effect, the diameter of the slurry column is slightly larger than the diameter of the nozzle, so when 100% filling rate is selected, the slurry will pile up and destroy the sample shape. Conversely, low fill rate will result in voids. Proper filling rate is an important factor in forming a good green part [63]. The nozzle diameter determines the thickness of the print layer and therefore affects surface roughness and dimensional accuracy. The small nozzle diameter results in low surface roughness and high dimensional accuracy [63]. However, due to the large thickness of the printed layer of 3DGP (compared to SLM, SEBM, and BJAM), obvious surface waves can be seen on the side of the sample. In addition, like the BJAM process, the printed green part shrinks during sintering [63].

The FFF WC-Co hardmetal sample is shown in Fig. 10. Due to the large nozzle diameter, the thickness of the printed layer of FFF is even larger than that of 3DGP, which makes the FFF sample have greater roughness [64]. An effective treatment is to surface treat the green part. Laser surface treatment is an effective method [115]. In addition, similar to BJAM, the sintering process in 3DGP and FFF also shrinks the sample [63, 64].

In summary, there are no macro defects in WC-Co samples fabricated by various AM processes when appropriate printing parameters and strategies are used. For the SDS processes, shrinkage due to sintering limits dimensional accuracy. For the 3DGP process and the FFF process, due to the large thickness of the printing layer, the sample has a large surface roughness, which requires surface treatment.

4 Microstructure

In SLM process of WC-Co, the powders in the center region of the laser beam absorb more energy than the powders at the edges, which cause the temperature in the center to be extremely high and exceeding the boiling point of Co [70]. The evaporation of Co will cause splashing and the reduction of Co that promotes the formation of very brittle ternary phases [73, 74, 116]. In addition, the reduction of Co will also cause the material to become brittle, which increases the trend of cracking. However, this will bring high hardness [73]. Co content is mainly affected by energy density, where high-energy density will cause severe Co reduction [109]. Uhlmann et al. indicated that the scanning speed and Co content show a U-shaped curve relationship, which needs further research [70].

Due to the high operating temperature, SLM also causes carbon loss in WC-Co [82, 83]. During the melting process, WC dissolves into the Co phase and forms a Co-based solid solution phase during solidification. However, the carbon loss leads to the transformation of WC carbide to the η phase (Co3W3C, Co6W6C, etc.) during solidification [117, 118]. The η phase is formed on the WC grains, and its formation is due to the interaction between Co and the dissolved W and C [119, 120]. The formation of the η phase requires the consumption of W and C in the Co-based solid solution, and its nucleation and production depend on the C content in WC and the W content in Co [121]. Experiments have shown that the W6Co6C phase content increased after sufficient cooling, indicating that the W6Co6C phase is in equilibrium in the W-C-Co system [122]. The hardness of η phase is higher than that of WC, but it is very brittle. The generation of this phase will make the sample brittle [123].

The Co/WC ratio also has an important effect on the properties of WC-Co. On the one hand, samples with high Co content are less susceptible to cracking. No crack was found in the sample with 75 wt.% Co, while the sample with 50 wt.% Co had obvious cracks [74, 75]. On the other hand, this ratio has a great influence on the phase composition in the sample. In the WC-Co system, the common forms of W are WC and W2C double carbides, WCo3 and W6Co7 bimetallic compounds, and W3Co3C, W4Co2C, and W6Co6C ternary carbides. Co usually exists as a solid solution [124, 125]. In samples with 75 wt.% and 72.5 wt.% Co content, only Co-based solid solution phase was present, while in the sample with 50 wt.% Co content, additional Co3W3C phase can occur. In the sample with 6 wt.% Co content, a W2C phase was formed [116]. The common WC-Co samples prepared by SLM do not contain more than 20 wt.% Co, and ternary and W2C phases are generally formed in these samples [111].

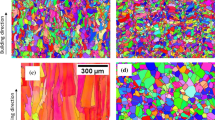

Because the volume energy density in SLM is very large and distributed non-uniformly, the microstructure of the WC-Co sample is also inhomogeneous as shown in Fig. 11 [70]. The sample has a typical molten pool structure (Fig. 12a). Since the molten pool has reached a temperature high enough to melt WC as well as evaporate Co and a large cooling gradient occurs during solidification, it has fine WC grains and a relatively low Co content. Large WC grains were generated along the fusion boundary of the molten pool [72]. Because SLM is a layer-by-layer manufacturing process, the upper part of each layer is reheated during the following melting passes. This results in a layered structure in which fine-grain layers and coarse grain layers alternate periodically in the vertical direction as shown in Fig. 12b [65]. Based on this, the microstructure of the sample can be controlled by energy density. High-energy density produces brittle structures with small WC grains and low Co content, and low-energy density produces tough structures with large WC grains and high Co content [70]. Besides, it was found that a high scanning speed can lead to a more uniform structure. In contrast, WC grain aggregation occurs at low scanning speeds [103].

Due to the similarity in process, SEBM samples also have similar layered structure as SLM samples as shown in Fig. 13a [41]. Typical microstructures of SEBMed WC-Co hardmetal are shown in Fig. 13. The microstructure is featured by layers with relatively fine WC grains and coarse WC grains (Fig. 13a, b). Konyashin et al. [41] suggested that the abnormally coarse-grained layers form as a result of highly localized heating of the WC-Co particles leading to the super-fast WC grain growth in a thin layer, where the electron beam directly interact with WC-Co. Figure 13c and d are scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of the WC/Co phase boundary. It can be seen that there are no complexes or other third phase inclusions on the phase boundary [41], though the material has experienced very high temperatures during the SEBM process. The super-fast heating and cooling during SEBM maybe the reason for the clear WC/Co interface with no reaction products, since the growth of a reaction product phase is usually a diffusion-controlled process, which needs sufficient time to occur [126,127,128]. Experiments on some other materials have proven that the residual stress of SEBM is less than that of SLM, because high operating temperature causes stress relief annealing [86].

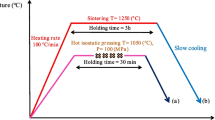

Compared to SLM, sintering temperature of BJAM is very low and its distribution is uniform, which means there is no evaporation of Co and very little carbon loss. Residual C during the debonding process reduces the formation of ternary phases [76]. In addition, the microstructure of the BJAM samples is usually more homogeneous than SLM and SEBM samples, due to the uniform sintering temperature distribution. The typical microstructure of BJAM samples after sintering consists of medium-sized (1.4–2.0 μm) and a coarse WC grain cluster with a size of about 20 μm is uniformly distributed in the binder phase as shown in Fig. 14. The grain cluster has a volume fraction of about 10% [78, 79]. The microstructure of end produce is related to its processes. When using the method of fabricating a carbide skeleton (by binder jetting) followed by infiltration of Co, excessive infiltration time will lead to the growth of WC grains, and sintering process can avoid random aggregation of WC grains [76]. The typical microstructure of samples prepared by the aforementioned binder jetting + infiltration process is shown in Fig. 15. It can be seen that the microstructure is also uniform, compared with the layer structures in SLMed and SEBMed samples. Some studies have suggested that different height positions in the BJAM sample have different microstructures. The higher the position, the lower the Co content, which means that the η phase is easier to form. When the position is too high, low Co content will even bring porosity [77].

Similar to BJAM, both 3DGP and FFF are processes that require sintering [89, 90]. Therefore, both 3DGP and FFF samples have a uniform microstructure [63, 64]. Because the slurry has good wetting and spreading properties, the 3DGP sample is uniform and nearly pore-free as shown in Fig. 16 [63]. The filament does not have the same good spreading property as the slurry in 3DGP, which results in wedge-shaped holes in the FFF sample as shown in Fig. 17 [64].

In summary, for the selective melting processes, the heat distribution is uneven, which can lead to the formation of layered structures. Super-fast WC grain growth was observed due to the very localized and high-temperature heating by laser or electron beam. The heat distribution in SLM is more uneven than in SEBM [84]. Local high temperatures in SLM cause problems such as carbon loss, Co evaporation, and high residual stress. Some studies suggest that according to the ternary phase diagram of W-C-Co, decarburization promotes the formation of ternary brittle phases[117, 118]. The evaporation of Co also makes the sample brittle [81]. Cracks form under the effect of residual stress [80]. Compared with the selective melting processes, the heat distribution in the SDS processes (BJAM, 3DGP, FFF) is uniform, which makes the sample have a uniform microstructure, fewer defects and lower residual stress. Figure 18 shows the microstructure of a conventional sintered WC-8Co sample [28]. It can be seen that the microstructure of the sample prepared by the SDS processes (Fig. 16) is more similar to that of the sample prepared by the conventional method, compared with the layered structure in SLM and SEBM samples.

5 Defects

There are usually many cracks in WC-Co samples manufactured by SLM. During printing, the thermal load on the material is about 2.5 × 105 W/cm2, which is one to two orders of magnitude higher than the thermal load in casting applications [129]. Because this heating is not uniform, there is a high-temperature difference between the molten pool and other areas, which results in very high longitudinal and transverse tensile residual stresses in the track after solidification [80]. High temperature in SLM causes evaporation of Co, which will lead to a decrease in the toughness of the material [81]. Cramer et al. suggested that a decrease in Co content increases the ternary phase generation window using a W-C-Co tenary phase diagram [77]. In addition, the thermal expansion coefficient mismatches between Co and WC [69, 129]. These factors, combined with residual stresses, lead to cracks in SLM WC-Co samples. In general, high-energy density and low binder content (Co) lead to high cracking tendency [70, 74].

The pores in the WC-Co sample are closely related to the energy density [109]. As shown in Fig. 19, a simulation of the relationship between the bubble movement in the molten pool and the linear energy density in the WC/Cu system in the SLM process was performed. It shows that low-energy density causes bubbles to move slowly and become trapped under the surface of the molten pool, and the excessive energy density makes the flow form of the bubbles tend to be deposited at the bottom of the molten pool or aggregated by the swirling flow in the molten pool, thereby increasing the porosity [68]. Decomposition of residual moisture in the powder and evaporation of the binder phase can also cause porosity. It was also found that the cracks in the porous samples were distributed between the pores, while the cracks in the dense samples were more continuous [70]. In addition, the powder may form rough pellets, making the powder unevenly distributed on the powder bed and lead to voids [103]. Some studies have suggested that the apparent density of irregular powders is lower than that of spherical powders, which are easier to form pores [65].

In the SLM of WC-Co, cracks occur when the energy density is too high, and pores cannot be reduced sufficiently when the energy density is too low. The high-energy density required for the low-porosity samples brings inevitable thermal shock, but preheating can be used to reduce the thermal gradient as well as the tendency of cracks. Some studies have preheated the powder and found that preheating can effectively reduce or avoid cracking completely [130, 131]. There are also experiments that use laser beams or furnaces to perform in situ temperature control of the samples [132, 133]. Another way to reduce defects is to use a suitable scanning strategy. Multi-pass strategy can increase energy density and reduce pores without increasing cracks. It was found that the scanning strategy in which energy density increased linearly for all laser passes can get better results [73]. Increasing the Co content can reduce the amount of ternary phases and cracks. No cracks and ternary phases are found in the sample with a Co amount of 75 wt.% [74, 116]. Increasing Co content can effectively reduce defects, but it is foreseeable that a large amount of Co will lead to poor mechanical properties.

In SEBM of WC-Co samples, the main defects are porosities, which are related to scan rate and electron beam current and can be eliminated by HIP (hot isostatic pressing) sintering. Both scan rate and electron beam current have a U-shaped curve relationship with porosity, which means there is a minimum of porosity under certain combinations of electron beam current and scanning rate [41].

Cracks rarely occur in BJAM WC-Co samples and the main defect is porosity. The generation of pores is mainly related to the conditions of post-treatment. Increasing the sintering temperature and pressure can reduce the porosity, as shown in Fig. 20 [78]. Too much Co used in the infiltration process will lead to larger pores [76]. This is because high liquid content captures more cavitation, which leads to more rearrangement of WC and more solidification shrinkage [76]. In the higher position of the sample, the inability of Co to reach leads to the formation of pores [77].

Due to the small residual stress in the sintered samples, there were no cracks in either the 3DGP or FFF samples. In 3DGP, the porosity depends on the solid loading of the slurry. As shown in Fig. 16, the reduction in solid loading in the slurry results in voids [63]. The pores in the FFF are shown in Fig. 17. The pores are caused by the low spreadability of the filament. Optimizing the printing strategy can reduce porosity [64].

To realize industrial applications of AMed WC-Co hardmetal parts, specific standards on AM of WC-Co hardmetals need to be established for evaluating the quality of the parts and for standardizing the manufacturing processes. Though there are a few published standards on metal AM, such as ASTM F3303-2018, ISO/ASTM52907-19, they are far from enough for the fast development of metal AM.

In summary, in SLM, the WC-Co samples are prone to cracks due to the evaporation of Co and formation of brittle ternary phases combine with high residual stress. Porosity is mainly affected by energy density, and powder properties such as flowability and participation in moisture also affect porosity. The porosity of the SEBM sample is mainly related to the printing parameters. Appropriate parameters can bring the lowest porosity. In addition, porosity can be reduced or even eliminated by HIP (hot isostatic pressing) sintering. For the SDS process, no cracks are generated due to the uniform energy distribution. The porosity of BJAM samples is mainly related to the sintering temperature. The porosity of 3DGP samples is mainly affected by the solid loading of the slurry. Porosity in both BJAM and 3DGP samples can be eliminated by improving manufacturing parameters. In the FFF process, wedge-shaped pores are generated due to poor spreadability of the filament. Pores in FFF can be reduced by optimizing printing strategies. The main causes of the defects formed in WC-Co samples fabricated by various AM processes are listed in Table 3.

6 Mechanical properties

In the AM process of WC-Co hardmetals, density is a primary indicator for quality. In SLM, the density of the sample increases as the energy density increases [73, 109], like reported in other materials [135,136,137]. When the parameters are suitable, the relative density can reach more than 95% [70, 73, 114]. Density of high porosity SLM samples can be increased by HIP (hot isostatic pressing) sintering [114]. In addition, the use of irregular powders results in a decrease in sample density [65]. BJAM makes samples easier to achieve high density, even without sintered process, the relative density can reach more than 96%. For sintered samples, the density can be as high as 98.7% [76]. In addition to the sintering process, the amount of Co and the infiltration time also affects the density of the sample. Too much Co and too long time will lead to a reduction in density [76].

For WC-Co parts, hardness is also an important performance indicator. The hardness of WC-Co samples prepared by SLM is usually around 1500 HV0.5 or 9.5 GPa [69, 70]. The hardness of the samples made by SEBM is 9.0~9.5GPa [41]. Due to the uneven structure of the SLM sample, its hardness distribution is also uneven. The hardness of the fine-grained region is higher than that of the coarse-grained region [69]. Adding Cr to WC-Co can limit the growth of WC grains, thereby improving the hardness. The hardness of the WC-CoCr samples prepared by SLM can reach 1840~2138 HV1 [72], which is higher than the hardness of WC-Co hardmetal samples (with similar WC grain size) fabricated by conventional methods (Fig. 1). Li et al. used NiAlCoCrCuFe high-entropy alloy instead of Co as the binding phase. The prepared sample showed uneven distribution of components, which can be divided into high W content region and low W content region. The hardness in the high W content region is 1306.8~1413.4 HV1, and the hardness in the low W content region is 711.7~1178.6 HV1 [66]. The hardness of samples prepared by BJAM is relatively low. The hardness of fine-grained region can reach 1300~1400HV0.5, and the hardness of coarse-grained cluster region is 1200~1300HV0.5 [78]. Areas with different infiltration heights have different Co content and different hardness. In areas with normal Co content, the hardness is 9.0 GPa, while in areas with lower Co content, the hardness can reach 14.1 GPa [77]. The hardness of WC-12Co sample prepared by BJAM is 1300–1400 HV, in which the WC grain size is in the range of 1.4–2.0 μm [78]. Compared with Fig. 1, it can be seen that the hardness of this sample is similar to that of the WC-12Co sample prepared by the traditional method. The average hardness of SLM samples with similar WC grain size reached 1515 HV, which is higher than the samples prepared by traditional methods [69].

Another important indicator of WC-Co samples is fracture toughness. The fracture toughness of BJAM samples can reach 17 MPa m1/2 [78], and even samples with fracture toughness of about 25 MPa m1/2 have been prepared [77, 138]. The fracture toughness of the sample prepared by SEBM is 13 MPa m1/2, but the author believes that this value cannot reflect the true fracture toughness of the sample, for the fracture toughness can reach 20 MPa m1/2 when calculated based on the cracks perpendicular to the WC layer [41].

The performance of 3DGP samples is mainly affected by the solid content of the slurry. A high solids content results in high density and hardness. The WC-20Co sample prepared with 56 vol% solid content slurry can obtain a relative density of 99.93% and a hardness of 87.7 HRA. The 47 vol% solids sample had a relative density of 88.58% and a hardness of 84.5 HRA [63].

An effective method to improve the mechanical properties of WC-Co samples is to reduce the WC grain size [10]. Because the resulting WC crystallite size largely depends on the initial one, WC-Co nano powders have attracted attention [75]. The WC grain size in the sample prepared from the nanostructured powder can reach 180 ± 50 nm, which is much smaller than the 330 ± 100 nm in conventional powder manufacturing samples [69]. Small grain size can bring high hardness and high wear resistance, but low toughness [31, 78]. The hardness of the nano-powder manufacturing sample can reach 2500 HV0.05, which is much higher than the 1550 HV0.05 of the conventional sample. In addition, the wear rate of the conventional sample was 1.3 times that of the nano-powder manufacturing sample. The fracture toughness of the nano powder sample is only 6.9 MPa m1/2, which is lower than the 8.9 MPa m1/2 of the conventional powder sample [31].

In summary, it can be seen that the SDS WC-Co samples (3DGP, BJAM, FFF) are easier to obtain high density, hardness similar to samples prepared by conventional methods, and the fracture toughness are excellent, while the selective melting (SM) samples (SLM, SEBM) have higher hardness but lower toughness. This is due to the uneven heat distribution of the selective melting process, especially in SLM, which leads to the evaporation of Co and the formation of ternary phases, both of which can make the sample hard and brittle. Cracks and uneven microstructures further reduce the toughness of the sample. The mechanical properties of all reported AMed WC-Co hardmetal samples are listed in Table 4.

7 Summary

In this paper, the current status of additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals is reviewed. The advantages and disadvantages of different AM processes used for producing WC-Co parts, including selective laser melting (SLM), selective electron beam melting (SEBM), binder jet additive manufacturing (BJAM), 3D gel-printing (3DGP), and fused filament fabrication (FFF) are discussed. The studies on microstructures, defects, and mechanical properties of WC-Co parts manufactured by different AM processes are reviewed. The main findings are summarized below:

- (1)

The properties of WC-Co samples are related to WC particle size and Co content [13,14,15,16]. The samples with high Co content have fewer defects, but too much Co can damage the mechanical properties of the samples. The reduction of the square root of WC particle size is linearly related to the increase in the wear resistance of the sample [15].

- (2)

Due to the uneven energy distribution, the microstructure of the SLM and SEBM WC-Co samples is also inhomogeneous [41, 70]. Because of the layer-by-layer printing process, the sample showed a layered structure with alternating coarse and fine grain layers [41, 65].

- (3)

In the SLM process, too high-energy density will cause Co evaporation and carbon loss, making the sample brittle [73, 74, 82, 83, 116]. Cracks occur under the effect of thermal stress [80]. When the energy density is low, the melting time of Co is insufficient to fill the pores, and the porosity of the sample is high [109].

- (4)

The main defect in the SEBM WC-Co sample are pores, which has a minimum under the appropriate combination of scan rate and electron beam current. Pores in the sample can be eliminated by HIP sintering [41].

- (5)

During BJAM, the WC-Co samples will shrink [78, 79]. Co content in the sample decreases with increasing height, and lower Co content led to the more favorable formation of the brittle η phase [77], which is detrimental to mechanical properties of WC-Co samples.

- (6)

In WC-Co samples manufactured by BJAM, porosity is related to sintering temperature, infiltration time, and amount of Co for infiltration [76, 78].

- (7)

By comparing WC-Co samples prepared by SDS processes (3DGP, BJAM, FFF) and selective melting processes (SLM, SEBM), SDS samples have higher density and better fracture toughness [76,77,78], selective melting samples have higher hardness [69, 70].

- (8)

The 3DGP and FFF processes have no requirements for powder flowability, but the WC-Co samples manufactured by these two processes have large surface roughness [63, 64].

8 Perspectives

-

(1)

Additive manufacturing technologies offer attractive advantages in terms of producing WC-Co hardmetal cutting tools with complex geometries, such as U-shaped or helical cooling channels inside. These internal, contour-adapted cooling channels allow higher cutting speeds and consequently, a remarkable increase in the productivity of the machining process.

-

(2)

Up to now, it is difficult to manufacture fully dense WC-Co parts with good properties using SLM. Therefore, more efforts are needed for developing an SLM process for the production of crack-free and dense (≥ 99 %) WC-Co parts.

-

(3)

The exposure of WC-Co to high-energy laser/electron beam may cause decarburization of WC, formation of carbides like W2C, and possible Co evaporation, which have detrimental effects on the properties of the final part. Thus, further efforts are needed for retarding the above-mentioned phenomenon. Preheating the base plate and the powder and using low-energy density printing parameters could be an effective measure.

-

(4)

For BJAM and 3DGP, it is much easier to achieve fully dense and high-quality WC-Co parts compared with SLM and SEBM, though the printing accuracy is lower and the process is more complicated. One challenge for BJAM of WC-Co parts is that Co content in the sample decreases with increasing height, and different Co content will lead to different phase composition. Therefore, further research is demanded in improving the BJAM process to achieve homogeneous BJAM WC-Co parts.

-

(5)

SEBM of WC-Co hardmetals faces similar challenges with SLM. Besides, in SEBM WC-Co samples, very intense local WC grain growth occurred, which leads to undesirable inhomogeneous microstructure. Further efforts are needed to retard the extremely fast growth of WC grains. Moreover, the cost of SEBM is higher than SLM.

-

(6)

One major application of additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals is producing cutting tools. Thus, cutting durability, fracture behavior, and wear mechanism of AMed WC-Co tools deserve great attention in the future.

-

(7)

Both 3DGP and FFF processes are easy to obtain samples with uniform microstructure and high density, and both have low requirements for powder properties. However, the large surface roughness caused by the large printing layer thickness is a disadvantage of these processes. Reducing surface roughness is a major challenge for both processes. In addition, more research is needed to reduce the porosity caused by poor spreadability of filament in the FFF process.

References

Jonke M, Klünsner T, Supancic P, Harrer W, Glätzle J, Barbist R, Ebner R (2017) Strength of WC-Co hard metals as a function of the effectively loaded volume. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 64:219–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2016.11.003

Teppernegg T, Klünsner T, Kremsner C, Tritremmel C, Czettl C, Puchegger S, Marsoner S, Pippan R, Ebner R (2016) High temperature mechanical properties of WC–Co hard metals. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 56:139–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2016.01.002

Kresse T, Meinhard D, Bernthaler T, Schneider G (2018) Hardness of WC-Co hard metals: preparation, quantitative microstructure analysis, structure-property relationship and modelling. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 75:287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.05.003

Yao Z, Stiglich J, Sudarshan T (1998) WC-Co enjoys proud history and bright future. Metal Powder Report 53:32–36

Gu D, Meiners W (2010) Microstructure characteristics and formation mechanisms of in situ WC cemented carbide based hardmetals prepared by selective laser melting. Mater Sci Eng A 527:7585–7592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2010.08.075

Ettmayer P (1989) Hardmetals and Cermets. Annu Rev Mater Sci 19:145–164. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ms.19.080189.001045

Armstrong RW (2011) The hardness and strength properties of WC-Co composites. Materials (Basel) 4:1287–1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4071287

Gurland J, Norton JT (1952) Role of the binder phase in cemened tungsten carbide-cobalt alloys. JOM 4:1051–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03397768

Yang T, Wang H-B, Song X-Y (2017) Corrosion resistance of HVOF-sprayed nano-and micon-structured WC-η coatings against Molten Zinc. J Inorg Mater-Beijing 32:806–812

Al-Aqeeli N, Saheb N, Laoui T, Mohammad K (2014) The synthesis of nanostructured WC-based hardmetals using mechanical alloying and their direct consolidation. J Nanomater 2014:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/640750

Kim HJ, Kweon YG, Chang RW (1994) Wear and erosion behavior of plasma-sprayed WC-Co coatings. J Therm Spray Technol 3:169–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02648274

Zhang H, Lin Z. (2019) Influence of ultrasonic excitation sealing on the corrosion resistance of HVOF-sprayed nanostructured WC-CoCr coatings under different corrosive environments. Coatings, 9, doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings9110724.

Petersson A, Ågren J (2005) Sintering shrinkage of WC–Co materials with different compositions. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 23:258–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2005.05.016

Lay S, Allibert CH, Christensen M, Wahnström G (2008) Morphology of WC grains in WC–Co alloys. Mater Sci Eng A 486:253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2007.09.019

Gee MG, Gant A, Roebuck B (2007) Wear mechanisms in abrasion and erosion of WC/Co and related hardmetals. Wear 263:137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2006.12.046

Marshall JM, Kusoffsky A (2013) Binder phase structure in fine and coarse WC–Co hard metals with Cr and V carbide additions. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 40:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2013.04.001

Upadhyaya GS (1998) 7 – Mechanical Behavior of Cemented Carbides. Cemented Tungsten Carbides:193–226

Baojun Z, Xuanhui Q, Ying T (2002) Powder injection molding of WC–8%Co tungsten cemented carbide. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 20:389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0263-4368(02)00015-x

Youseffi M, Menzies IA (2013) Injection moulding of WC–6Co powder using two new binder systems based on montanester waxes and water soluble gelling polymers. Powder Metall 40:62–65. https://doi.org/10.1179/pom.1997.40.1.62

Lin D, Xu J, Shan Z, Chung ST, Park SJ (2015) Fabrication of WC-Co cutting tool by powder injection molding. Int J Precis Eng Manuf 16:1435–1439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-015-0189-8

Xie XC, Lin CG, Jia CC, Cao RJ (2015) Effects of process parameters on quality of ultrafine WC/12Co injection molded compacts. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 48:305–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.09.022

Zhou J, Huang B, Wu E (2003) Extrusion moulding of hard-metal powder using a novel binder system. J Mater Process Technol 137:21–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-0136(02)01058-0

Fraunhofer I (2016) Droplet-based additive manufacturing of hard metal components by thermoplastic 3D printing (T3DP). J Ceram Sci Technol 8:155–160. https://doi.org/10.4416/JCST2016-00104

Ferstl H, Barbist R, Rough SL, Wilson DI (2012) Influence of visco-elastic binder properties on ram extrusion of a hardmetal paste. J Mater Sci 47:6835–6848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-012-6627-4

Petersson A, Ågren J (2005) Rearrangement and pore size evolution during WC–Co sintering below the eutectic temperature. Acta Mater 53:1673–1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2004.12.017

Upadhyaya GS (1998). Cemented tungsten carbides: production, properties and testing, William Andrew

Wang Z, Jia J, Wang B, Wang Y. (2019) Two-step spark plasma sintering process of ultrafine grained WC-12Co-0.2VC cemented carbide. Materials (Basel) 12, doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12152443

Su W, Sun Y, Wang H, Zhang X, Ruan J (2014) Preparation and sintering of WC–Co composite powders for coarse grained WC–8Co hardmetals. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 45:80–85

Simonelli M, Tse YY, Tuck C (2014) Effect of the build orientation on the mechanical properties and fracture modes of SLM Ti–6Al–4 V. Mater Sci Eng A 616:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2014.07.086

Liu Y, Yang Y, Mai S, Wang D, Song C (2015) Investigation into spatter behavior during selective laser melting of AISI 316 L stainless steel powder. Mater Des 87:797–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2015.08.086

Grigoriev S, Tarasova T, Gusarov A, Khmyrov R, Egorov S. (2019) Possibilities of manufacturing products from cermet compositions using nanoscale powders by additive manufacturing methods. Materials (Basel), 12, doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12203425

Hou H, Simsek E, Ma T, Johnson NS, Qian S, Cissé C, Stasak D, Hasan NA, Zhou L, Hwang Y et al (2019) Fatigue-resistant high-performance elastocaloric materials made by additive manufacturing. Science 366:1116–1121. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax7616

Todaro CJ, Easton MA, Qiu D, Zhang D, Bermingham MJ, Lui EW, Brandt M, StJohn DH, Qian M (2020) Grain structure control during metal 3D printing by high-intensity ultrasound. Nat Commun 11:142. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13874-z

Lin T-C, Cao C, Sokoluk M, Jiang L, Wang X, Schoenung JM, Lavernia EJ, Li X (2019) Aluminum with dispersed nanoparticles by laser additive manufacturing. Nat Commun 10:4124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12047-2

DebRoy T, Mukherjee T, Milewski JO, Elmer JW, Ribic B, Blecher JJ, Zhang W (2019) Scientific, technological and economic issues in metal printing and their solutions. Nat Mater 18:1026–1032. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-019-0408-2

Edgar J, Tint S (2015) “Additive manufacturing technologies: 3D printing, rapid prototyping, and direct digital manufacturing”, 2nd Edition. Johnson Matthey Technol Rev 59:193–198. https://doi.org/10.1595/205651315x688406

Herderick E (2011) Additive manufacturing of metals: a review. Mater Sci Technol 1413

Kumar S (2009) Manufacturing of WC–Co moulds using SLS machine. J Mater Process Technol 209:3840–3848

Herzog D, Seyda V, Wycisk E, Emmelmann C (2016) Additive manufacturing of metals. Acta Mater 117:371–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2016.07.019

Gu DD, Meiners W, Wissenbach K, Poprawe R (2013) Laser additive manufacturing of metallic components: materials, processes and mechanisms. Int Mater Rev 57:133–164. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743280411y.0000000014

Konyashin I, Hinners H, Ries B, Kirchner A, Klöden B, Kieback B, Nilen RWN, Sidorenko D (2019) Additive manufacturing of WC-13%Co by selective electron beam melting: Achievements and challenges. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 84:84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.105028

DebRoy T, Wei HL, Zuback JS, Mukherjee T, Elmer JW, Milewski JO, Beese AM, Wilson-Heid A, De A, Zhang W (2018) Additive manufacturing of metallic components – process, structure and properties. Prog Mater Sci 92:112–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2017.10.001

Drescher P; Sarhan M, Seitz H (2016) An investigation of sintering parameters on titanium powder for electron beam melting processing optimization. Materials (Basel), 9, doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9120974

Hernández-Nava E, Tammas-Williams S, Smith C, Leonard F, Withers P, Todd I, Goodall R (2017) X-ray tomography characterisation of lattice structures processed by selective electron beam melting. Metals 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/met7080300

Maizza G, Caporale A, Polley C, Seitz H (2019) Micro-macro relationship between microstructure, porosity, mechanical properties, and build mode parameters of a selective-electron-beam-melted Ti-6Al-4 V alloy. Metals 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/met9070786

Veiga A, Artaza S (2019). Experimental investigation of the influence of wire arc additive manufacturing on the machinability of titanium parts. Metals, 10. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/met10010024

Wang F, Williams S, Colegrove P, Antonysamy AA (2013) Microstructure and mechanical properties of wire and arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4 V. Metall Mater Trans A 44:968–977

Marinelli G, Martina, F; Ganguly S, Williams S (2019) Grain refinement in an unalloyed tantalum structure by combining wire+ arc additive manufacturing and vertical cold rolling. Addit Manuf 101009.

Marinelli G, Martina F, Ganguly S, Williams S (2019) Development of wire+ arc additive manufacture for the production of large-scale unalloyed tungsten components. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 82:329–335

Tucho WM, Cuvillier P, Sjolyst-Kverneland A, Hansen V (2017) Microstructure and hardness studies of Inconel 718 manufactured by selective laser melting before and after solution heat treatment. Mater Sci Eng A 689:220–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2017.02.062

Mazur M, Leary M, McMillan M, Elambasseril J, Brandt M (2016) SLM additive manufacture of H13 tool steel with conformal cooling and structural lattices. Rapid Prototyp J 22:504–518

Seyedkashi A, Kang K, Moon W (2019) Analysis of melt-pool behaviors during selective laser melting of AISI 304 stainless-steel composites. Metals, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/met9080876

Jin W, Zhang C, Jin S, Tian Y, Wellmann D, Liu W (2020) Wire arc additive manufacturing of stainless steels: a review. Appl Sci 10

Zai L, Zhang C, Wang Y, Guo W, Wellmann D, Tong X, Tian Y (2020) Selective laser melting of precipitation-hardened martensitic stainless steels: a review. Metals.

Arısoy YM, Criales LE, Özel T, Lane B, Moylan S, Donmez A (2016) Influence of scan strategy and process parameters on microstructure and its optimization in additively manufactured nickel alloy 625 via laser powder bed fusion. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 90:1393–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-9429-z

Chauvet E, Kontis P, Jägle EA, Gault B, Raabe D, Tassin C, Blandin J-J, Dendievel R, Vayre B, Abed S (2018) Hot cracking mechanism affecting a non-weldable Ni-based superalloy produced by selective electron Beam Melting. Acta Mater 142:82–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2017.09.047

Promoppatum P, Onler R, Yao S-C (2017) Numerical and experimental investigations of micro and macro characteristics of direct metal laser sintered Ti-6Al-4 V products. J Mater Process Technol 240:262–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2016.10.005

Vaithilingam J, Goodridge RD, Hague RJM, Christie SDR, Edmondson S (2016) The effect of laser remelting on the surface chemistry of Ti6al4V components fabricated by selective laser melting. J Mater Process Technol 232:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2016.01.022

Sidambe AT, Tian Y, Prangnell PB, Fox P (2019) Effect of processing parameters on the densification, microstructure and crystallographic texture during the laser powder bed fusion of pure tungsten. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 78:254–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.10.004

Sidambe AT, Judson DS, Colosimo SJ, Fox P (2019) Laser powder bed fusion of a pure tungsten ultra-fine single pinhole collimator for use in gamma ray detector characterisation. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 84:104998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.104998

Schmidtke K, Palm F, Hawkins A, Emmelmann C (2011) Process and mechanical properties: applicability of a scandium modified Al-alloy for laser additive manufacturing. Phys Procedia 12:369–374

Chou R, Milligan J, Paliwal M, Brochu M (2015) Additive manufacturing of Al-12Si alloy via pulsed selective laser melting. JOM 67:590–596

Zhang X, Guo Z, Chen C, Yang W (2018) Additive manufacturing of WC-20Co components by 3D gel-printing. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 70:215–223

Lengauer W, Duretek I, Fürst M, Schwarz V, Gonzalez-Gutierrez J, Schuschnigg S, Kukla C, Kitzmantel M, Neubauer E, Lieberwirth C (2019) Fabrication and properties of extrusion-based 3D-printed hardmetal and cermet components. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 82:141–149

Chen J, Huang M, Fang ZZ, Koopman M, Liu W, Deng X, Zhao Z, Chen S, Wu S, Liu J, Qi W, Wang Z (2019) Microstructure analysis of high density WC-Co composite prepared by one step selective laser melting. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 84, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.104980

Li C-W, Chang K-C, Yeh A-C (2019) On the microstructure and properties of an advanced cemented carbide system processed by selective laser melting. J Alloys Compd 782:440–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.12.187

Gu D (2015) In situ WC-cemented carbide-based hardmetals by selective laser melting (SLM) additive manufacturing (AM): microstructure characteristics and formation mechanisms. In Laser Additive Manufacturing of High-Performance Materials, Springer: pp. 151-173.

Dai D, Gu D (2014) Thermal behavior and densification mechanism during selective laser melting of copper matrix composites: simulation and experiments. Mater Des 55:482–491

Domashenkov A, Borbély A, Smurov I (2016) Structural modifications of WC/Co nanophased and conventional powders processed by selective laser melting. Mater Manuf Process 32:93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2016.1176195

Uhlmann E, Bergmann A, Gridin W (2015) Investigation on additive manufacturing of tungsten carbide-cobalt by selective laser melting. Procedia CIRP 35:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2015.08.060

Berger C; Abel J, Pötschke J, Moritz T. Properties of additive manufactured hardmetal components produced by fused filament fabrication (FFF). In Proceedings of Euro PM 2018 Congress and Exhibition.

Campanelli SL, Contuzzi N, Posa P, Angelastro A (2019) Printability and microstructure of selective laser melting of WC/Co/Cr powder. Materials (Basel), 12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12152397

Fortunato A, Valli G, Liverani E, Ascari A (2019) Additive manufacturing of WC-Co cutting tools for gear production. Lasers Manuf Mater Proc 6:247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40516-019-00092-0

Khmyrov RS, Safronov VA, Gusarov AV (2016) Obtaining crack-free WC-Co alloys by selective laser melting. Phys Procedia 83:874–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2016.08.091

Khmyrov RS, Safronov VA, Gusarov AV (2017) Synthesis of nanostructured WC-Co hardmetal by selective laser melting. Procedia IUTAM 23:114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.piutam.2017.06.011

Cramer CL, Nandwana P, Lowden RA, Elliott AM (2019) Infiltration studies of additive manufacture of WC with Co using binder jetting and pressureless melt method. Addit Manuf 28:333–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.04.009

Cramer CL, Wieber NR, Aguirre TG, Lowden RA, Elliott AM (2019) Shape retention and infiltration height in complex WC-Co parts made via binder jet of WC with subsequent Co melt infiltration. Addit Manuf 29:100828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.100828

Enneti RK, Prough KC, Wolfe TA, Klein A, Studley N, Trasorras JL (2018) Sintering of WC-12%Co processed by binder jet 3D printing (BJ3DP) technology. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 71:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2017.10.023

Enneti RK, Prough KC (2019) Wear properties of sintered WC-12%Co processed via binder Jet 3D printing (BJ3DP). Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 78:228–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.10.003

Gusarov AV, Pavlov M, Smurov I (2011) Residual stresses at laser surface remelting and additive manufacturing. Phys Procedia 12:248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2011.03.032

Uhlmann E, Bergmann A, Bolz R (2018) Manufacturing of carbide tools by selective laser melting. Proc Manuf 21:765–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.02.182

Kear BH, Skandan G, Sadangi RK (2001) Factors controlling decarburization in HVOF sprayed nano-WC/Co hardcoatings. Scr Mater 44:1703–1707. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1359-6462(01)00867-3

Sara R (1965) Phase Equilibria in the system tungsten—carbon. J Am Ceram Soc 48:251–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1965.tb14731.x

Körner C (2016) Additive manufacturing of metallic components by selective electron beam melting—a review. Int Mater Rev 61:361–377

Everhart T, Hoff P (1971) Determination of kilovolt electron energy dissipation vs penetration distance in solid materials. J Appl Phys 42:5837–5846

Sochalski-Kolbus L, Payzant EA, Cornwell PA, Watkins TR, Babu SS, Dehoff RR, Lorenz M, Ovchinnikova O, Duty C (2015) Comparison of residual stresses in Inconel 718 simple parts made by electron beam melting and direct laser metal sintering. Metall Mater Trans A 46:1419–1432

Berman B (2012) 3-D printing: the new industrial revolution. Business Horizons 55:155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.11.003

Spierings AB, Voegtlin M, Bauer T, Wegener K (2016) Powder flowability characterisation methodology for powder-bed-based metal additive manufacturing. Prog Addit Manuf 1:9–20

Ren X, Shao H, Lin T, Zheng H (2016) 3D gel-printing—an additive manufacturing method for producing complex shape parts. Mater Des 101:80–87

Kukla C, Gonzalez-Gutierrez J, Burkhardt C, Weber O, Holzer C The production of magnets by FFF-fused filament fabrication. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the Euro PM2017 Congress & Exhibition, Milan, Italy; pp. 1-5.

Gonzalez-Gutierrez J, Cano S, Schuschnigg S, Kukla C, Sapkota J, Holzer C (2018) Additive manufacturing of metallic and ceramic components by the material extrusion of highly-filled polymers: a review and future perspectives. Materials 11:840

Schmidt M, Merklein M, Bourell D, Dimitrov D, Hausotte T, Wegener K, Overmeyer L, Vollertsen F, Levy GN (2017) Laser based additive manufacturing in industry and academia. CIRP Ann 66:561–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2017.05.011

Bourell D, Kruth JP, Leu M, Levy G, Rosen D, Beese AM, Clare A (2017) Materials for additive manufacturing. CIRP Ann 66:659–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2017.05.009

Kruth JP, Levy G, Klocke F, Childs THC (2007) Consolidation phenomena in laser and powder-bed based layered manufacturing. CIRP Ann 56:730–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2007.10.004

Paul CP, Alemohammad H, Toyserkani E, Khajepour A, Corbin S (2007) Cladding of WC–12 Co on low carbon steel using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Mater Sci Eng A 464:170–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2007.01.132

Yang Y, Lu JB, Luo ZY, Wang D (2012) Accuracy and density optimization in directly fabricating customized orthodontic production by selective laser melting. Rapid Prototyp J 18:482–489. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552541211272027

Gu D, Shen Y (2008) Direct laser sintered WC-10Co/Cu nanocomposites. Appl Surf Sci 254:3971–3978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.12.028

Kruth JP, Froyen L, Van Vaerenbergh J, Mercelis P, Rombouts M, Lauwers B (2004) Selective laser melting of iron-based powder. J Mater Process Technol 149:616–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2003.11.051

Gibson I, Rosen D, Stucker B (2015) Powder bed fusion processes. In Additive Manufacturing Technologies, Springer: pp. 107-145.

Hackel L, Rankin JR, Rubenchik A, King WE, Matthews M (2018) Laser peening: a tool for additive manufacturing post-processing. Addit Manuf 24:67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.09.013

Maamoun AH, Elbestawi M, Dosbaeva GK, Veldhuis SC (2018) Thermal post-processing of AlSi10Mg parts produced by selective laser melting using recycled powder. Addit Manuf 21:234–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.03.014

Gu D, Shen Y, Xiao J (2008) Influence of processing parameters on particulate dispersion in direct laser sintered WC–Cop/Cu MMCs. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 26:411–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2007.09.005

Bricín D, Špirit Z, Kříž A (2018) Metallographic analysis of the suitability of a WC-Co powder blend for selective laser melting technology. Mater Sci Forum 919:3–9. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.919.3

Kruth JP, Kumar S, Van Vaerenbergh J (2005) Study of laser-sinterability of ferro-based powders. Rapid Prototyp J 11:287–292. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552540510623594

Kluczynski J, Sniezek L, Grzelak K, Mierzynski J (2018) The influence of exposure energy density on porosity and microhardness of the SLM additive manufactured elements. Materials (Basel) 11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11112304

Do T, Kwon P, Shin CS (2017) Process development toward full-density stainless steel parts with binder jetting printing. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 121:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2017.04.006

Wong KV, Hernandez A (2012) A review of additive manufacturing. ISRN Mech Eng 2012:1–10

Bai Y, Williams CB (2015) An exploration of binder jetting of copper. Rapid Prototyp J 21:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/rpj-12-2014-0180

Kumar S, Czekanski A (2017) Optimization of parameters for SLS of WC-Co. Rapid Prototyp J 23:1202–1211. https://doi.org/10.1108/rpj-10-2016-0168

Popovich A Sufiiarov V (2016) Metal powder additive manufacturing. In New Trends in 3D Printing, IntechOpen

Bricin D, Kriz A (2018) Assessment of usability of WC-Co powder mixtures for SLM. Manuf Technol 18:719–726. https://doi.org/10.21062/ujep/166.2018/a/1213-2489/MT/18/5/719

Sames WJ, List FA, Pannala S, Dehoff RR, Babu SS (2016) The metallurgy and processing science of metal additive manufacturing. Int Mater Rev 61:315–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09506608.2015.1116649

Aramian, A.; Razavi, S.M.J.; Sadeghian, Z.; Berto, F.J.A.M. A review of additive manufacturing of cermets. 2020, 101130.

Ku N, Pittari JJ, Kilczewski S, Kudzal A (2019) Additive manufacturing of cemented tungsten carbide with a cobalt-free alloy binder by selective laser melting for high-hardness applications. JOM 71:1535–1542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-019-03366-2

Burkhardt C, Freigassner P, Weber O, Imgrund P, Hampel S Fused filament fabrication (FFF) of 316L green parts for the MIM process. In Proceedings of European Congress and Exhibition on Powder Metallurgy. European PM Conference Proceedings; pp. 1-7.

Grigoriev SN, Khmyrov RS, Shevchukov AP, Gusarov AV, Tarasova TV (2017) Phase composition and microstructure of WC–Co alloys obtained by selective laser melting. Mechanics & Industry 18:714. https://doi.org/10.1051/meca/2017059

Lugscheider E, Reimann H, Pankert R (1982) n-Carbides in Co--W--C and Fe--W--C Alloys. Z Met 73:321–324

Kublii VZ, Velikanova TY (2004) Ordering in the carbide W2C and phase equilibria in the tungsten ? carbon system in the region of its existence. Powder Metall Met Ceram 43:630–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11106-005-0032-3

Pollock C, Stadelmaier H (1970) The eta carbides in the Fe − W− C and Co − W− C systems. Metall Trans A 1:767–770. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02811752

Skogsmo J, Nordén H (1992) The formation of n-phase in cemented carbides during chemical vapour deposition. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 11:49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-4368(92)90084-f

Swank W, Fincke J, Haggard D, Irons G, Bullock R (1994) Thermal spray industrial application. ASM International, Materials Park, pp 313–318

Thiele S, Sempf K, Jaenicke-Roessler K, Berger L-M, Spatzier J (2010) Thermophysical and microstructural studies on thermally sprayed tungsten carbide-cobalt coatings. J Therm Spray Technol 20:358–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-010-9558-0

Lovelock HLV (1998) Powder/processing/structure relationships in WC-Co thermal spray coatings: a review of the published literature. J Therm Spray Technol 7:357–373. https://doi.org/10.1361/105996398770350846

Bondar A, Bochvar N, Dobatkina T, Krendelsberger N (2010) Carbon–cobalt–tungsten. In Refractory metal systems, Springer pp. 249-289.

Johansson T, Uhrenius B (2013) Phase equilibria, isothermal reactions, and a thermodynamic study in the Co-W-C system at 1150 °C. Metal Science 12:83–94. https://doi.org/10.1179/msc.1978.12.2.83

Zhang C, Robson JD, Haigh SJ, Prangnell PBJM (2019) Interfacial segregation of alloying elements during dissimilar ultrasonic welding of AA6111 aluminum and Ti6Al4V titanium. Metall Mater Trans A 50:5143–5152

Zhang C, Liu WJML (2019) Abnormal effect of temperature on intermetallic compound layer growth at aluminum-titanium interface: the role of grain boundary diffusion. Mater Lett 254:1–4

Zhang C, Liu WJML (2019) Non-parabolic Al3Ti intermetallic layer growth on aluminum-titanium interface at low annealing temperatures. Mater Lett 256:126624

Vrancken B, King WE, Matthews MJ (2018) In-situ characterization of tungsten microcracking in selective laser melting. Procedia CIRP 74:107–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.08.050

Liu Q, Danlos Y, Song B, Zhang B, Yin S, Liao H (2015) Effect of high-temperature preheating on the selective laser melting of yttria-stabilized zirconia ceramic. J Mater Process Technol 222:61–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2015.02.036

Liu Q, Song B, Liao H (2014) Microstructure study on selective laser melting yttria stabilized zirconia ceramic with near IR fiber laser. Rapid Prototyp J 20:346–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/rpj-12-2012-0113

Kaczmar JW, Pietrzak K, Włosiński W (2000) The production and application of metal matrix composite materials. J Mater Process Technol 106:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-0136(00)00639-7

Wilkes J, Hagedorn YC, Meiners W, Wissenbach K (2013) Additive manufacturing of ZrO2-Al2O3ceramic components by selective laser melting. Rapid Prototyp J 19:51–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552541311292736

Kumar S (2018) Process chain development for additive manufacturing of cemented carbide. J Manuf Process 34:121–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2018.05.036

Haberland C, Elahinia M, Walker JM, Meier H, Frenzel J (2014) On the development of high quality NiTi shape memory and pseudoelastic parts by additive manufacturing. Smart Mater Struct 23:104002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0964-1726/23/10/104002

Scipioni Bertoli U, Wolfer AJ, Matthews MJ, Delplanque J-PR, Schoenung JM (2017) On the limitations of volumetric energy density as a design parameter for selective laser melting. Mater Des 113:331–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2016.10.037

Li XP, Ji G, Chen Z, Addad A, Wu Y, Wang HW, Vleugels J, Van Humbeeck J, Kruth JP (2017) Selective laser melting of nano-TiB 2 decorated AlSi10Mg alloy with high fracture strength and ductility. Acta Mater 129:183–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2017.02.062

Cramer CL, Aguirre TG, Wieber NR, Lowden RA, Trofimov AA, Wang H, Yan J, Paranthaman MP, Elliott AM (2019) Binder jet printed WC infiltrated with pre-made melt of WC and Co. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater 87:105137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.105137

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51605287, and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai, grant number 16ZR1417100. This work was also supported by the fund of State Key Laboratory of Long-life High Temperature Materials (DTCC28EE190933).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Zhang, C., Wang, D. et al. Additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals: a review. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 108, 1653–1673 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-05389-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-05389-5