Abstract

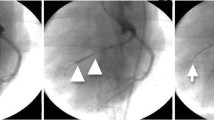

The surgical technique employed to determine an experimental ischemic damage is a major factor in the subsequent process of myocardial scar development. We set out to establish a minimally invasive porcine model of myocardial infarction using cardiac contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (ce-MRI) as the basic diagnostic tool. Twenty-seven domestic pigs were randomized to either temporary or permanent occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD). Temporary occlusion was achieved by inflation of a percutaneous balloon in the left anterior descending artery directly beyond the second diagonal branch. Occlusion was maintained for 30 or 45 min, followed by reperfusion. Permanent occlusion was achieved via thrombin injection. Thirteen animals died peri- or postinterventionally due to arrhythmias. Fourteen animals survived the 30-min ischemia (four animals; group 1), the 45-min ischemia (six animals; group 2), or the permanent occlusion (4 animals; group 3). Coronary angiography and ce-MRI were performed 8 weeks after coronary occlusion to document the coronary flow grade and the size of myocardial scar tissue. The LAD was patent in all animals in groups 1 and 2, with normal TIMI flow; in group 3 animals, the LAD was totally occluded. Fibrosis of the left ventricle in group 1 (4.9 ± 4.4%; p = 0.008) and group 2 (9.4 ± 2.9%; p = 0.05) was significantly lower than in group 3 (14.5 ± 3.9%). Wall thickness of the ischemic area was significantly lower in group 3 versus group 1 and group 2 (2.9 ± 0.3, 5.9 ± 0.7, and 6.1 ± 0.7 mm; p = 0.005). The extent of late enhancement of the left ventricle was also significantly higher in group 3 (16.9 ± 2.1%) compared to group 1 (5.3 ± 5.4%; p = 0.003) and group 2 (9.7 ± 3.4%, p = 0.013). In conclusion, the present model of minimally invasive infarction coupled with ce-MRI may represent a useful alternative to the open chest model for studies of myocardial infarction and scar development.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Reimer KA, Jennings RB (1979) The “wavefront phenomenon” of myocardial ischemic cell death. II. Transmural progression of necrosis within the framework of ischemic bed size (myocardium at risk) and collateral flow. Lab Invest 40(6):633–644

Reimer KA, Lowe JE, Rasmussen MM et al (1977) The wavefront phenomenon of ischemic cell death. 1. Myocardial infarct size vs. duration of coronary occlusion in dogs. Circulation 56(5):786–794

Horstick G, Heimann A, Gotze O et al (1997) Intracoronary application of C1 esterase inhibitor improves cardiac function and reduces myocardial necrosis in an experimental model of ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation 95(3):701–708

Horstick G, Berg O, Heimann A et al (2001) Application of C1-esterase inhibitor during reperfusion of ischemic myocardium: dose-related beneficial versus detrimental effects. Circulation 104(25):3125–3131

Klein HH, Puschmann S, Schaper J et al (1981) The mechanism of the tetrazolium reaction in identifying experimental myocardial infarction. Virchows Arch 393(3):287–297

Kim RJ, Chen EL, Lima JA et al (1996) Myocardial Gd-DTPA kinetics determine MRI contrast enhancement and reflect the extent and severity of myocardial injury after acute reperfused infarction. Circulation 94(12):3318–3326

Robotham JL, Stuart RS, Borkon AM et al (1988) Effects of changes in left ventricular loading and pleural pressure on mitral flow. J Appl Physiol 65(4):1662–1675

Duncker DJ, Klassen CL, Ishibashi Y et al (1996) Effect of temperature on myocardial infarction in swine. Am J Physiol 270(4 Pt 2):H1189–H1199

Hale SL, Dave RH, Kloner RA (1997) Regional hypothermia reduces myocardial necrosis even when instituted after the onset of ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol 92(5):351–357

Schwartz LM, Verbinski SG, Vander Heide RS et al (1997) Epicardial temperature is a major predictor of myocardial infarct size in dogs. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29(6):1577–1583

Bitkover CY, Hansson LO, Valen G et al (2000) Effects of cardiac surgery on some clinically used inflammation markers and procalcitonin. Scand Cardiovasc J 34(3):307–314

Cohen MV, Eldh P (1973) Experimental myocardial infarction in the closed-chest dog:controlled production of large or small areas of necrosis. Am Heart J 86(6):798–804

Chareonthaitawee P, Christenson SD, Anderson JL et al (2006) Reproducibility of measurements of regional myocardial blood flow in a model of coronary artery disease: comparison of H215O and 13NH3 PET techniques. J Nucl Med 47(7):1193–1201

Croisille P, Moore CC, Judd RM et al (1999) Differentiation of viable and nonviable myocardium by the use of three-dimensional tagged MRI in 2-day-old reperfused canine infarcts. Circulation 99(2):284–291

Kraitchman DL, Bluemke DA, Chin BB et al (2000) A minimally invasive method for creating coronary stenosis in a swine model for MRI and SPECT imaging. Invest Radiol 35(7):445–451

Yang Y, Foltz WD, Graham JJ et al (2007) MRI evaluation of microvascular obstruction in experimental reperfused acute myocardial infarction using a T1 and T2 preparation pulse sequence. J Magn Reson Imaging 26:1486–1492

Horstick G, Bierbach B, Schlindwein P et al (2007) Resistance of the internal mammary artery to restenosis: a histomorphologic study of various porcine arteries. J Vasc Res 45:45–53

Schaper W (1984) Experimental infarcts and the microcirculation. Raven Press, New York, p 12

Schaper W, Binz K, Sass S et al (1987) Influence of collateral blood flow and of variations in MVO2 on tissue-ATP content in ischemic and infarcted myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 19(1):19–37

Hale SL, Kloner RA (1988) Left ventricular topographic alterations in the completely healed rat infarct caused by early and late coronary artery reperfusion. Am Heart J 116(6 Pt 1):1508–1513

Reffelmann T, Sensebat O, Birnbaum Y et al (2004) A novel minimal-invasive model of chronic myocardial infarction in swine. Coron Artery Dis 15(1):7–12

Naslund U, Haggmark S, Johansson G et al (1992) A closed-chest myocardial occlusion-reperfusion model in the pig: techniques, morbidity and mortality. Eur Heart J 13(9):1282–1289

Krombach GA, Kinzel S, Mahnken AH et al (2005) Minimally invasive close-chest method for creating reperfused or occlusive myocardial infarction in swine. Invest Radiol 40(1):14–18

Horstick G, Berg O, Heimann A et al (1999) Surgical procedure affects physiological parameters in rat myocardial ischemia:need for mechanical ventilation. Am J Physiol 276(2 Pt 2):H472–H479

Opitz CF, Mitchell GF, Pfeffer MA et al (1995) Arrhythmias and death after coronary artery occlusion in the rat. Continuous telemetric ECG monitoring in conscious, untethered rats. Circulation 92(2):253–261

Wiggers H, Klebe T, Heickendorff L et al (1997) Ischemia and reperfusion of the porcine myocardium: effect on collagen. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29(1):289–299

Gerber BL, Rochitte CE, Melin JA et al (2000) Microvascular obstruction and left ventricular remodeling early after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 101(23):2734–2741

Lluch S, Moguilevsky HC, Pietra G et al (1969) A reproducible model of cardiogenic shock in the dog. Circulation 39(2):205–218

Rees JR, Redding VJ (1968) Experimental myocardial infarction by a wedge method: early changes in collateral flow. Cardiovasc Res 2(1):43–53

Jacobey JA, Taylor WJ, Smith GT et al (1962) A new therapeutic approach to acute coronary occlusion. I. Production of standardized coronary occlusion with microspheres. Am J Cardiol 9:60–73

Smiseth OA, Lindal S, Mjos OD et al (1983) Progression of myocardial damage following coronary microembolization in dogs. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [A] 91(2):115–124

Haines DE, Verow AF, Sinusas AJ et al (1994) Intracoronary ethanol ablation in swine: characterization of myocardial injury in target and remote vascular beds. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 5(1):41–49

Lakkis N (2000) New treatment methods for patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol 15(3):172–177

Suzuki M, Asano H, Tanaka H et al (1999) Development and evaluation of a new canine myocardial infarction model using a closed-chest injection of thrombogenic material. Jpn Circ J 63(11):900–905

Petersen SE, Voigtlander T, Kreitner KF et al (2003) Late improvement of regional wall motion after the subacute phase of myocardial infarction treated by acute PTCA in a 6-month follow-up. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 5(3):487–495

Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A et al (2000) The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med 343(20):1445–1453

Petersen SE, Horstick G, Voigtlander T et al (2003) Diagnostic value of routine clinical parameters in acute myocardial infarction: a comparison to delayed contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Delayed enhancement and routine clinical parameters after myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 19(5):409–416

Horstick G, Petersen SE, Voigtlander T et al (2004) Cardio-MRT. The multimodal functional analysis of the future. Z Kardiol 93(Suppl 4):IV36–IV47

Vosseler M, Abegunewardene N, Hoffmann N et al (2009) Area at risk and viability after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion can be determined by contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Surg Res 43:13–23

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

N. Abegunewardene and M. Vosseler contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abegunewardene, N., Vosseler, M., Gori, T. et al. Usefulness of MRI to Differentiate Between Temporary and Long-Term Coronary Artery Occlusion in a Minimally Invasive Model of Experimental Myocardial Infarction. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 32, 1033–1041 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-009-9596-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-009-9596-5