Abstract

The primary progressive aphasias are a heterogeneous group of focal ‘language-led’ dementias that pose substantial challenges for diagnosis and management. Here we present a clinical approach to the progressive aphasias, based on our experience of these disorders and directed at non-specialists. We first outline a framework for assessing language, tailored to the common presentations of progressive aphasia. We then consider the defining features of the canonical progressive nonfluent, semantic and logopenic aphasic syndromes, including ‘clinical pearls’ that we have found diagnostically useful and neuroanatomical and other key associations of each syndrome. We review potential diagnostic pitfalls and problematic presentations not well captured by conventional classifications and propose a diagnostic ‘roadmap’. After outlining principles of management, we conclude with a prospect for future progress in these diseases, emphasising generic information processing deficits and novel pathophysiological biomarkers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The primary progressive aphasias (PPA) are a diverse group of disorders that collectively present with relatively focal degeneration of the brain systems that govern language. Despite much recent attention in the scientific literature [1, 2], these ‘language-led dementias’ remain daunting for even experienced clinicians to diagnose and manage. This is not surprising: PPA is uncommon (estimated prevalence is conservatively around three cases per 100,000 [3, 4]), the underlying pathology is heterogeneous and generally inaccessible and the functions principally targeted are uniquely complex. Although patients with PPA have been described for well over a century [5], the true significance of these disorders was only appreciated quite recently [6, 7] and the paradigm of selective brain network degeneration caused by pathogenic protein spread has transformed our understanding of neurodegenerative disease [8]. While challenging, accurate clinical diagnosis of PPA is worth striving for: these patients are often affected in late middle life, with devastating implications for family life, work and social functioning.

In this review, we outline an approach to the diagnosis and management of PPA in the clinic and at the bedside, distilled from our accumulated experience of meeting and caring for these patients. We firstly present a clinical framework for assessing language functions, tailored in particular to the major syndromic presentations of PPA (Tables 1 and 2, Figs. 1 and 2). We then consider these presentations in detail. Three major forms of PPA—nonfluent–agrammatic variant (nfvPPA), semantic variant (svPPA) and logopenic variant (lvPPA)—comprise the canonical syndromes currently recognised in consensus diagnostic criteria [9] (see Table S1, Supplementary Material on-line). These syndromes are distinguished by the language deficits with which they present and associated cognitive, neurological and neuroanatomical profiles and tend to have distinct neuropathological substrates. Key features of PPA syndromes are summarised in Tables 1, 2 and 3 and Fig. 1; additional ‘clinical pearls’ that we have found useful in diagnosis of each syndrome (but which are not widely discussed in the literature of these conditions) are presented in Table 4. Following the taxonomy of classical (stroke) aphasiology, nfvPPA might be anticipated to align with Broca’s aphasia, svPPA with transcortical sensory aphasia and lvPPA with Wernicke’s or conduction aphasia. However, such clinical correspondences are loose, at best. This probably reflects the very different nature of the underlying disease processes, and most pertinently, the distributed neural network basis of PPA [10]. One important corollary is that PPA syndromes extend (cognitively and neuroanatomically) beyond the province of language, to involve other complex behavioural functions. The clinical challenges posed by PPA foreshadow significant unresolved issues in the nosology and neurobiology of these conditions [1, 2, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Here we highlight potential diagnostic pitfalls including atypical variant presentations of PPA not well captured by standard criteria (Table 1) and propose a diagnostic ‘roadmap’ (Fig. 3). After outlining principles of management of PPA, we conclude with a prospect for future developments.

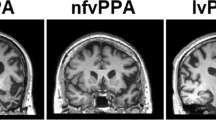

Neuroanatomical and cognitive profiles of the canonical syndromes of progressive aphasia. The top panels present coronal T1-weighted brain MRI sections (in radiological convention, with the left hemisphere on the right) of patients with typical syndromes of nonfluent–agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia (nfvPPA), showing asymmetric (predominantly left sided) inferior frontal, insular and anterior–superior temporal gyrus atrophy; semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA), showing asymmetric (predominantly left sided) anterior inferior and mesial temporal lobe atrophy; and logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA), showing atrophy predominantly involving left temporo-parietal junction (posterior–superior temporal and inferior parietal cortices). The cut-away brain schematic (right) indicates the distributed cerebral networks involved in each syndrome; the left cerebral hemisphere is projected forward and major neuroanatomical associations are in bold italics: a, amygdala; ATL, anterior temporal lobe; BG, basal ganglia; h, hippocampus; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus/frontal operculum; ins, insula; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; PMC, posterior medial cortex (posterior cingulate, precuneus); STG, superior temporal gyrus; TPJ, temporo-parietal junction. The ‘target diagrams’ below show typical profiles of neuropsychological test performance for each syndrome; concentric circles indicate the percentile scores relative to a healthy age-matched population and the distance along the radial dimension represents the level of functioning in the following cognitive domains: ex, executive skills; l, literacy skills; n, naming; nm, nonverbal memory; pr, phrase repetition; s, sentence processing; v, visuo-spatial; vm, verbal memory; wm, word meaning; wr, word repetition

Example of a picture that can be used to elicit conversational speech (reproduced with permission of Professor EK Warrington). A scene of this kind can be used to assess naming and also to probe aspects of language comprehension, at the level of single words (using questions such as, ‘Where is the sandcastle?’) and grammatical relations embodied in sentences (using instructions such as, ‘Point to the thing that the boy is holding above the boat’)

A clinical ‘roadmap’ for diagnosis of canonical primary progressive aphasia syndromes, synthesising key features on history and examination. The ‘forks’ comprising the middle section of the map indicate major decision points, for corroboration using the more detailed framework presented in Table 2. Neuropsychological assessment (where available) is used both to support and quantify the clinical impression and to reveal additional cognitive deficits that may not be emphasised in the clinic but define the overall syndrome (see Fig. 1). Brain imaging (wherever feasible, MRI) is essential to rule out brain tumours and other non-degenerative pathologies that can occasionally present with progressive aphasia; it also has an important ‘positive’ role in corroborating the neuroanatomical diagnosis (see Fig. 1). Ancillary investigations such as CSF examination are used to stratify pathologies within particular syndromes (e.g., lvPPA), with a view to prognosis and treatment. A significant minority of cases will not be diagnosed by this algorithm, falling into the still poorly defined category of ‘atypical’ progressive aphasias (see text and Table 1). lvPPA, logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia; nfvPPA, nonfluent–agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia; svPPA, semantic variant primary progressive aphasia

A clinical framework for assessing language functions in primary progressive aphasia

When confronted by an aphasic patient, it is important firstly to establish the context of the language disturbance. This usually requires the help of an informant who knows the patient well and can supply reliable background information. A diagnosis of PPA requires that speech or language dysfunction was the initial and most salient clinical complaint (see Table S1). However, the patient’s previous verbal skills (including formal education, occupation, bilingualism or any specific developmental difficulties such as stammering or dyslexia) are relevant to interpreting current deficits. It is also necessary to determine the extent of any uncorrected peripheral hearing or visual impairments as these can impact significantly on everyday communication and performance on language tests. In defining the history of the language problem, it is essential to establish the circumstances of onset and very first symptoms (often noticed by the patient’s family), overall duration and tempo. The length of the history bears strongly on the interpretation of deficits, since PPA syndromes tend to converge over time [17]. In PPA, a history of gradual, but unrelenting decline over a number of months or several years is typical, but some apparent fluctuation is not uncommon, particularly under conditions that stress the language system, such as public speaking or conversations by telephone or in a non-native tongue. There may have been a sentinel event such as a family celebration or minor head injury that first drew attention to the patient’s difficulties; informants may interpret this as an acute onset but a searching history usually reveals a more insidious prodrome.

The profile of the patient’s language dysfunction then allows the clinico-anatomical syndrome to be characterised (see Table 1). Fundamentally, language supports communication—the understanding, creation and delivery of messages. In assessing a patient’s speech, it is useful to analyse the various stages at which the idea for a message is first generated, the content (or vocabulary) of the message, its structure (assembly) and delivery. Similarly, in assessing understanding of language, it is useful to analyse the separable stages at which messages are perceived and then invested with meaning. These operations are differentially vulnerable to particular PPA syndromes and can be explored using targeted questions on history and a small set of core language tests (Table 2). The patient’s use of written language typically echoes the speech disorder as the illness evolves. Examples of patients’ transcribed spoken and written productions are presented in Table 3 (corresponding speech sound files are provided in Supplementary Material on-line).

In neurology, the history generally suggests the diagnosis while the examination corroborates the historical suspicion. This precept is equally valid for language disorders, with the caveat that certain aspects of language are difficult to differentiate on the story alone. One key example (not often called upon in everyday communication) is the ability to repeat messages verbatim, which is central to the characterisation of PPA (see Table 1) and should be examined explicitly. Like the testing of pupillary and spinal reflexes in general neurology, certain language tests such as speech repetition or picture naming rapidly assay a number of connected neural operations: if such tests are performed normally, this demonstrates the overall integrity of the system but if a problem is found, it is necessary to establish where in the system it lies. The most important principle in examining speech is to obtain an adequate sample; for this purpose, it is convenient to carry a picture that will encourage the patient to talk and provide a prop for directed tests (one example is shown in Fig. 2).

Alongside the core clinical tests in Table 2 we list some more formal equivalents that might be administered by a neuropsychologist. However, neuropsychological assessment does not simply endorse the bedside impression. If available, it adds considerable value, particularly in quantifying language capacities in relation to standardised population norms and in the context of estimated premorbid ability, in tracking change in language functions over time and in measuring associated capacities that together with aphasia define the overall cognitive phenotype and may also affect the assessment of language.

Canonical syndromes of primary progressive aphasia: nonfluent–agrammatic

Clinical presentation

Patients with nfvPPA present with slow, effortful, hesitant and distorted speech (Table 3; Supplementary sound files 1 and 2). Speech sound errors are generally prominent and there is often a history of ‘slurring’ or mispronunciations. Words tend to be missed out and conversation is sometimes strikingly telegraphic; errors of grammar (mainly affecting syntax, function words such as articles and conjunctions and verb usage) typically emerge and sometimes dominate the presentation [11, 18]. Inability to understand more complex conversations or instructions may signify impaired comprehension of sentences, which is generally integral to any grammatical deficit [19]. Speech is usually very much more affected than written communication at the outset and patients tend to resort increasingly to nonverbal means of expression, manifestly frustrated by their inability to communicate.

On examination, there is usually marked difficulty producing polysyllabic words and sequences of syllables (e.g., ‘puh-tuh-kuh’) to command, due to impaired motor programming of speech and reduced articulatory agility. This can be brought out by asking the patient to repeat longer words or read aloud. The listener is left with an almost painful sense of the patient’s struggle to speak (not experienced with other forms of PPA). In contrast to peripheral dysarthrias which tend to provoke stumbling consistently over particular sounds, the misshapen speech of patients with nfvPPA is protean, with characteristic ‘groping’ after the target sound: ‘speech apraxia’ [20]. This is often accompanied by apraxia of posed orofacial movements such as yawning or whistling, disproportionate to any limb apraxia [21]; asked to perform an orofacial gesture, the patient may emphatically echo the command (‘Cough!’) while remaining quite unable to enact it. Speech sound errors can be classified according to whether syllables are wrongly selected (‘phonemic’ or ‘phonological’ errors) or misformed during execution (‘phonetic’ or articulatory errors). These arise at different stages during message production but often defy explicit categorisation in the clinic and the distinction is seldom of practical importance. It is useful to examine a specimen of the patient’s writing (Table 3): besides revealing spelling (phonological dysgraphic) errors, this is a more reliable index of associated agrammatism than the patient’s speech, which may be constricted by the sheer effort involved.

The clinical spectrum of nfvPPA is the most diverse of the canonical PPA syndromes, with a number of variant sub-syndromes (see Table 1). The most important of these is ‘pure’ progressive speech apraxia associated with orofacial apraxia, but without agrammatism or other aphasic features, which has been proposed to constitute a distinct entity [22, 23]. While apraxia of speech may indeed be relatively pure at presentation [11], in our experience most of these patients do in time develop aphasia, initially detected on detailed neuropsychological assessment. Some clinical ‘pearls’ we have found useful in the diagnosis of nfvPPA are presented in Table 4.

Neuroanatomy

This syndrome is associated with atrophy of inferior frontal gyrus (‘Broca’s area’) and insula cortex in the dominant hemisphere (Fig. 1), with variable extension along and around the superior temporal gyrus. These brain regions play fundamental roles in language output, motor speech programming and sentence processing [10]. Atrophy is generally best appreciated as widening of the left Sylvian fissure on a T1-weighted coronal MRI scan [24]. However, this may be subtle on cross-sectional imaging and is easily overlooked on ‘routine’ reporting lists, by even experienced observers [25]. Moreover, rotated slices may simulate asymmetry; scrolling through a number of slices is useful to check that the direction of any apparent asymmetry is consistent (and therefore real). A neuroradiological phenotype of homologous right-sided peri-Sylvian atrophy is recognised, though its clinical correlates remain ill-defined [26, 27]; several of our patients with this finding have had notable central nonverbal auditory deficits or dysprosody [28].

Key associations

General intellect is often remarkably well preserved, though a degree of executive dysfunction is usual and may be accompanied behaviourally by apathy or impulsivity [29, 30]. Depression can be significant, particularly as insight is usually retained. Many patients with nfvPPA will develop Parkinsonism, often evolving into a progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal syndrome with associated supranuclear gaze palsy, postural instability, pseudobulbar dysfunction and limb apraxia, dystonia or ‘alien’ phenomena [31, 32].

The pathological associations of nfvPPA are (in keeping with the clinical spectrum) more heterogeneous than other PPA syndromes. A majority of patients will have a tauopathy such as progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal degeneration at post-mortem though a substantial (and still uncertain) minority represent TDP-43 or Alzheimer pathology [3, 12, 33,34,35]. While there are currently few reliable predictors of underlying pathology in individual patients [36], prominent apraxia of speech and parkinsonism are more closely associated with tauopathy than with TDP-43 pathology [12, 35]. nfvPPA is less likely to be genetically mediated than the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia though it is somewhat more heritable than other PPA syndromes, around 30% of patients having a relevant family history [37]. Causative mutations in all major (GRN, MAPT, C9orf72) genes causing frontotemporal dementia have been identified and at least some of these genetic forms may prove clinically distinct with more detailed phenotyping [11].

Canonical syndromes of primary progressive aphasia: semantic

Clinical presentation

In striking contrast to nfvPPA, patients with svPPA exhibit well structured, well articulated language that is relentlessly bereft of substance (Table 3; Supplementary sound file 3). This typically begins as difficulty finding words (particularly nouns)—sometimes described as losing ‘memory for names’—and an inability to express thoughts with precision. The patient’s verbal messages become progressively more circumlocutory and empty, as fine-grained content (less frequently used vocabulary, such as ‘dachshund’ or ‘ladybird’) is replaced by increasingly generic ciphers (‘animal’, ‘thing’). Blunting of verbal nuance in svPPA may predate diagnosis by many years [38]. The true nature of the deficit is revealed in a history (almost pathognomonic for svPPA) of asking the meaning of previously familiar words (‘What’s broccoli?’): this is not merely a problem of accessing words in memory, but erosion of vocabulary itself. Indeed, svPPA is the paradigmatic disorder of semantic memory, the cognitive system that stores (rather than the autobiographical events that populate ‘episodic’ memory) knowledge about objects and concepts and allows us to attribute meaning to the world at large [6, 39]. The language deficit in svPPA is fundamentally associated with loss of meaning about objects and people. While language impairment usually leads the presentation, deficits of nonverbal knowledge inevitably appear later in the course and ultimately blight all sensory channels [39,40,41,42]. More rarely, patients present with inability to recognise objects (visual agnosia) or familiar people (prosopagnosia) by sight.

Earlier in the course of the illness, the conversation of patients with svPPA is easily passed as normal by the casual listener, due to its well preserved surface structure and fluency, even garrulousness [11]. However, closer attention generally reveals severe anomia. Because anomia is a common feature of a number of aphasias, it is important to distinguish carefully those cases (for example, in svPPA) where this follows degradation of the word store (primary semantic impairment) from the more usual scenario, in which retrieval of words from storage is principally affected. It is failure to comprehend or recognise words and objects rather than anomia per se that defines a semantic deficit. Impaired comprehension of single words in svPPA can be demonstrated by asking the patient to describe an item nominated by the examiner or to select it from an array or scene (see Fig. 2).

Assessment of other language channels corroborates the semantic deficit. When reading aloud or writing, patients with svPPA characteristically ‘regularise’ words according to superficial phonological ‘rules’ in place of learned vocabulary (e.g., sounding ‘island’ as ‘izland’ or ‘sew’ as ‘soo’): so called ‘surface’ dyslexia or dysgraphia (Table 3). English is a particularly fertile field for such deficits as it is replete with irregular ‘exception’ words, but analogous examples exist in other languages (disproportionately affecting, for example, kanji versus kana script in Japanese [43]). Assessment of nonverbal semantic domains generally requires more detailed neuropsychological assessment, though in clinic visual knowledge might be conveniently sampled (within the limits of verbal comprehension and without requiring naming) by asking the patient to indicate the purpose of a familiar tool (such as a comb or stapler), to identify associations of a pictured item (‘which thing could be used in the garden?’; Fig. 2) or to supply biographical information from photographs of familiar people. Across verbal and nonverbal semantic domains, loss of meaning in svPPA follows a stereotyped pattern. More specific knowledge about less familiar (low frequency) and atypical items is lost before knowledge of highly familiar and typical items; failures of recognition are accompanied by ‘over-generalisation’ errors that tend to regularise objects to a generic type (for example, the patient may draw a four-legged peacock or a rhino lacking its horn); and errors are highly consistent over time, so that the meanings of words and objects, once lost, are irretrievable [44, 45]. These features of svPPA have informed neural computational models of the underlying cognitive architecture of semantic memory and its breakdown [46, 47]. Some clinical ‘pearls’ relevant to svPPA are listed in Table 4.

Neuroanatomy

On neuroimaging, svPPA has a hallmark pattern of asymmetric, focal cerebral atrophy chiefly involving the dominant anteroinferior and mesial temporal lobe, including amygdala and anterior hippocampus [9, 48]. This is most easily visualised on a T1-weighted coronal MRI scan (Fig. 1). The profile of atrophy shows a clear gradient within the temporal lobe, with ‘knife-blade’ destruction of the pole and relatively sparing of superior temporal gyrus and more posterior temporal cortices. This signature is consistently observed across patients and unmistakeable; in our experience, it is invariably present at diagnosis in typical svPPA and indeed (in contrast to nfvPPA) often ‘the scan is worse than the patient’. Over time, atrophy spreads to involve more posterior temporal regions and homologous gyri in the contralateral temporal lobe as well as orbitofrontal cortex [49, 50]: regions that together constitute the core of the brain’s semantic memory network [39, 47]. This distinctive atrophy profile has provided an important neuroanatomical grounding for cognitive models of svPPA, according to which anterior temporal cross-modal ‘hub’ cortex interacts with more posterior, relatively modality-specific cortices across both left and right temporal lobes [47].

Some patients exhibit a ‘mirror’ profile of predominant right anterior temporal lobe atrophy. For unknown reasons, these cases are rarer than their leftward-asymmetric counterparts and usually present with profound disturbances of social and emotional behaviour or prosopagnosia, indicating the breakdown of knowledge about people [51, 52].

Key associations

A behavioural syndrome similar to that defining the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia characteristically develops in svPPA and indeed, these syndromes can occasionally be difficult to distinguish, even after a careful history. Initially, behavioural features in svPPA may be quite subtle, but tend to manifest earlier and more floridly in patients with more marked right (non-dominant) temporal lobe involvement and become universal as the march of disease involves the frontotemporal networks that regulate social responsiveness [39, 47]. Symptoms such as absent or misplaced empathy, social disinhibition and faux pas, a more fatuous sense of humour and pathological sweet tooth are common in both svPPA and behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia [29, 53,54,55,56,57]. Within this spectrum, certain behavioural features, such as food faddism, exaggerated reactions to pain and ambient temperature, behavioural rigidity with clock-watching and obsessional interest in numbers, puzzles (especially Sudoku and jigsaws) and music (‘musicophilia’) seem particularly linked to svPPA [30, 53, 58,59,60]. A unifying theme here may be impaired understanding of emotional and somatic signals due to both deficient and over-generalised responses to sensory information [41, 42, 55, 56, 61], analogous to recognition failures and ‘regularisation errors’ in other cognitive domains. An impoverished concept of self due to diminished awareness of bodily signals may contribute to reduced empathy and an increased rate of suicidality in svPPA relative to other neurodegenerative syndromes [61, 62]. Insight and awareness of deficits often appear to be retained, but may be superficial or incomplete. In contrast to nfvPPA, associated neurological signs are not typically found in svPPA, though parkinsonian or motor neuron features may develop later in the course [31, 63].

Completing the picture of a highly coherent clinical, anatomical and pathological syndrome, most cases of svPPA have TDP-43 (type C) pathology at post-mortem [12, 33, 35]. Primary tauopathies and Alzheimer’s disease account for a small minority and may have certain distinguishing phenotypic markers (for example, prominent acalculia or extrapyramidal signs in association with Pick’s disease pathology [12, 35]). Most cases are sporadic though occasional pathogenic mutations are reported [4] and may be relatively more likely if motor features are present (e.g., associated motor neuron disease with TBK1 mutations [64]).

Canonical syndromes of primary progressive aphasia: logopenic

Clinical presentation

The most recently described of the major PPA syndromes is (in more than one sense) the most problematic. This is due chiefly to the issue of demarcating it clinically from typical Alzheimer’s disease and the lack of a readily agreed, unifying syndromic deficit in lvPPA to set against the speech production (message production) failure that defines nfvPPA and the word comprehension (message understanding) failure that defines svPPA. The clinical picture in lvPPA is usually dominated by word-finding difficulty and conversational lapses, for which the syndrome is named (Greek, ‘lack of words’; Table 3, Supplementary sound file 4). Early on, ‘tip-of-the-tongue’ hesitations are often prominent. Some patients develop a rather mannered style of conversation, likened by one spouse to a ‘Jane Austen character’. Interrupted sentences that tend to trail off may give the impression of agrammatism though without the frank syntactic dislocations of nfvPPA [18]. Speech sound or spelling errors are frequently described. The patient may struggle to understand more complex sentences and to hold verbal information in mind. While language is (by definition) the leading and dominant issue, there is frequently a history of associated extra-linguistic difficulties extending to the realms of memory (e.g., forgetfulness, repetitiveness or route-finding problems), praxis (e.g., use of work equipment, tools or household gadgets) or visuo-spatial awareness (e.g., inability to judge distances accurately, find exits or locate items in plain sight) [65, 66].

On examination, the patient’s speech is derailed by word retrieval pauses and (often marked) anomia, though this is usually not as severe (from such an early stage) as in svPPA. This syndrome illustrates the difficulty of dichotomising PPA syndromes as ‘nonfluent’ versus ‘fluent’: patients with lvPPA in general do not talk fluently, yet their speech sounds quite different to the mutilated utterances of nfvPPA (compare Supplementary sound files 1, 2 and 4). Generally, phonological speech sound errors can be detected, usually taking the form of syllable misselections that are enunciated clearly and not accompanied by the false starts and distortions that characterise nfvPPA. Reading aloud is similarly marred by syllabic substitutions, highlighted by sounding out non-words (e.g., proper names) that rely on phonological decoding rather than learned vocabulary. Analogous errors of written spelling are often evident (Table 3). The diagnostic feature of lvPPA that distinguishes it from other PPA syndromes is early and disproportionate difficulty repeating heard phrases and sentences versus single words [67] (see Table 2). This signifies an impairment of verbal (phonological) working memory, also indexed as a reduced auditory span for repetition of random digit strings [16]. While digit span is often also reduced in nfvPPA, in that syndrome repetition of single words and repetition of phrases are comparably degraded. Other dominant (and often, bi-hemispheric) posterior cortical signs such as limb apraxia and visual apperceptive agnosia can frequently be elicited in lvPPA. This extra-linguistic cognitive phenotype tends to be more extensive and severe than in other PPA syndromes at a comparable stage of clinical evolution (see Fig. 1). Some clinical ‘pearls’ relevant to lvPPA are presented in Table 4.

Neuroanatomy

The key neuroimaging association is asymmetric atrophy mainly involving the temporo-parietal junction zone of the dominant hemisphere, appearing as widening of the posterior left Sylvian fissure on a T1-weighted coronal MRI scan [68] (Fig. 1). This locus potentially accounts for many features of the language phenotype, since posterior superior temporal and inferior parietal cortices are intimately involved in decoding speech sounds and activating phonological representations to link verbal semantic stores to language output [10, 16, 69]. However, there is often extension of atrophy more anteriorly with involvement of other structures (notably the hippocampi) and the overall extent and pattern of atrophy varies widely between individual patients.

Key associations

A number of patients with lvPPA exhibit generalised anxiety, irritability and increased clinging (emotionally and physically) to their primary caregivers [29, 70, 71]. Similar behavioural features may occur with posterior cortical atrophy (the ‘visual’ Alzheimer variant syndrome) or indeed in typical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurological signs are usually sparse [32], but include myoclonus, which may be peri-oral. Some patients go on to develop a corticobasal syndrome [71].

In most cases, lvPPA is a variant presentation of Alzheimer’s disease. This explains the extensive phenotypic overlap of lvPPA with both later-stage typical Alzheimer’s disease and the posterior cortical atrophy variant, corroborated at post-mortem as well as on neuropsychological, CSF (raised phosphorylated tau levels, raised ratio of total tau to beta-amyloid1-42) and amyloid-PET case series [35, 70,71,72]. On the other hand, cases of lvPPA lacking Alzheimer markers are consistently represented across series; the pathological substrates have not been clarified, but these may point to separable clinico-anatomical sub-syndromes [16, 68, 71,72,73]. Although lvPPA is generally a sporadic disorder, some caution is called for in cases without Alzheimer markers, since pathogenic progranulin gene mutations have been reported in this subgroup [11, 68].

Toward the diagnosis: a path with pitfalls

Accurate and early identification of PPA syndromes is essential for clinical counselling and planning appropriate management. Beyond clinical characterisation, molecular stratification will become increasingly important with trials of candidate disease-modifying treatments on the horizon [35]. However, most patients presenting with a language complaint will not have PPA and further, a number of patients with PPA (as many as 40% in some series) do not conform closely to one of the canonical syndromic diagnoses [3, 13, 15, 16, 34]. Some of these less common, atypical variants are in Table 1.

In Fig. 3, we present a ‘roadmap’ for diagnosis of PPA syndromes that we have found useful in clinic. Key diagnostic decision ‘forks’ rest on the historical and examination findings outlined in Tables 1 and 2 and on neuropsychological assessment where available. Structural brain imaging (ideally, MRI) is essential in all cases of suspected PPA, both to rule out other causes of progressive language failure and more positively, to identify features of particular radiological phenotypes (Fig. 1). Where initial MRI features are borderline (notably in nfvPPA and lvPPA) it may be helpful to repeat the scan after an interval of a year or so, as directly comparing serial studies of the culprit brain region is often revealing. Functional MRI and FDG-PET in PPA are not in routine clinical use though there is considerable potential interest in applying such techniques to define aberrant and compensatory language network changes, with a view to future therapeutic trials [74, 75].

Having arrived at a syndromic diagnosis, it may be appropriate to investigate further to determine the underlying proteinopathy—including CSF examination or amyloid-PET scanning for Alzheimer neurodegeneration markers. These ancillary investigations may be relevant, for example, in deciding to trial a cholinesterase inhibitor in a patient with nfvPPA or more generally, in forecasting the overall outlook of the illness in earlier stage disease. We discuss the possibility of genetic risk in all younger patients with nfvPPA and genetic screening should be considered in any patient with PPA who has a relevant family history, particularly where there this raises suspicion of a frontotemporal dementia. Discussions in clinic around genetic testing broach a number of sensitive issues and should ideally involve other family members.

We next consider some common potential pitfalls on the path to diagnosis.

The patient with late stage or ‘global’ aphasia

All PPA syndromes tend ultimately to give rise to global language failure with mutism or sparse, stereotyped utterances [76] as well as more widespread cognitive decline. Accordingly, diagnosis later in the course may be more informed by associated neurological features such as Parkinsonism. On the other hand, ‘mixed’ aphasia does not of itself signify advanced disease: some patients exhibit deficits that transcend canonical syndromic boundaries early on (see Table 1). In our experience, this includes cases with progranulin mutations [11] and Alzheimer’s, Pick’s and other pathological associations are reported [16, 35].

The unhelpful scan

Neuroimaging findings in nfvPPA and lvPPA can be subtle and an equivocal scan does not rule out the diagnosis. A related issue concerns the diagnostic relevance of visualised abnormalities; PPA syndromes can be caused by unusual pathologies (for example, primary leukodystrophies and prion disease), but most meningiomas and arachnoid cysts will be incidental. Cerebrovascular changes of small vessel ischaemia are commonly found in older patients but seldom if ever cause a canonical PPA syndrome (though word-finding difficulty commonly accompanies vascular cognitive impairment).

The older patient

It is likely that PPA is underdiagnosed in older patients in whom language deficits are more likely to be ascribed uncritically to Alzheimer’s disease or undifferentiated ‘dementia’ [4]. On the other hand, impaired word retrieval commonly occurs in amnestic Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia and other diseases and may be a salient early feature even if it does not dominate the presentation [10, 77]. These patients often do poorly on naming tasks and may substitute semantically related ‘paraphasias’ (e.g., ‘rhino’ instead of ‘hippo’). The speech of advanced typical Alzheimer’s disease has characteristics similar to lvPPA, though close analysis suggests that these syndromes are linguistically distinct at earlier stages [78]. Accurate diagnosis is worthwhile, given the quite different management issues that these groups present.

The patient with comorbidities

Interpretation of apparent language deficits should be cautious in older patients with a history of developmental dyslexia or longstanding peripheral hearing loss, especially when the recent symptoms target phonology or articulation and if additional cognitive involvement is subtle. Often a period of follow-up will establish the nature of the deficit. Performance on language tests should always be calibrated for premorbid literacy skills in the test language.

The worried well or ‘functional’ patient

Word-finding difficulty is a very common complaint in patients attending memory clinics [10]. Many will be experiencing the effects of normal ageing and intercurrent stressors; they typically describe inefficiency in recalling names or clearly expressing their thoughts when preoccupied or fatigued and have no evidence of language deficits on objective testing. A taxonomy of neurologically unexplained, ‘functional’ or ‘non-organic’ speech disorders has been described [79]. In our experience, these cases are rare and tend to present as excessively deliberate, but immaculately executed speech or with isolated disturbances of prosody (‘melody’ of speech). Dysprosody is a regular accompaniment of nfvPPA and ‘pure’ primary progressive dysprosodia (leading to the development of other aphasic features) is a rare satellite syndrome in the PPA spectrum (Table 1). Indeed, ‘foreign accent syndrome’ has been described as a presentation of PPA [80]. Our patients with nfvPPA (and occasional cases of primary progressive dysprosodia) have exhibited degraded native accents or loss of a previously competent second language accent, rather than developing a facsimile foreign accent. ‘Organic’ dysprosody tends to be brought out by circumstances (such as singing or reciting) calling for heightened control of vocal intonation [26, 81].

When interpreting a language disorder as ‘neurologically unexplained’, it is important to appreciate that bona fide PPA syndromes can have quite counter-intuitive manifestations. An expert second opinion may be useful and the passage of time (and lack of clinical and radiological evolution) often clarifies the situation.

An outline of management

Patients with PPA generally live for a number of years following diagnosis, with evolving deficits and specific needs at each stage of the illness. Widely accepted clinical staging markers are presently lacking, however, the major PPA syndromes collectively raise similar management challenges and these broadly require the integration of non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches.

Non-pharmacological strategies

Management begins with diagnosis; this is often delayed due to the lack of experience with these conditions in the wider medical community and the value of a clear explanation for patients and families should never be underestimated. Diagnosis supports future planning (including discussions around end-of-life care) and mobilisation of appropriate social services. Supportive care is still the mainspring of management for all PPA syndromes. Patients and caregivers need clear advice about driving safety, work arrangements, safeguarding and finances (particularly in younger patients who may have dependent children or elderly relatives). Later in the course, and especially in nfvPPA, dysphagia (due to motor dyscontrol and/or impulsivity) may become a significant issue necessitating expert advice from a dietician or speech therapist and where appropriate, consideration of assisted feeding. Patients should also be monitored for the emergence of other motor and neurological features that impact on mobility and activities of daily life. Early detection of physical deficits is key because these tend to herald a step change in functional status and care requirements. It may be useful to provide the patient and caregiver with a medical card or bracelet as the ability to communicate diagnosis and needs fails due to severe communication and/or behavioural decline. If available, involvement in a lay support group dedicated to PPA or frontotemporal dementia often provides much-needed psychological support and practical advice (in the United Kingdom, see: http://www.raredementiasupport.org/ppa/). Support and respite for caregivers are often overlooked, but vital to maintaining patients in the community.

Speech and language therapy in PPA has an important role in providing communication aids and strategies. Even simple measures such as picture books and cards listing frequent and important words and phrases that the patient can carry may be of great practical value (particularly in nfvPPA). More structured therapy aims to provide person-centred and goal directed interventions to alleviate impairment (e.g., word-relearning tasks) and to maintain daily life functioning (e.g., ordering in a coffee shop) [82, 83]. These can in principle be tailored to the particular PPA syndrome: for example, word-relearning techniques might focus on object features (use, location, appearance) in patients with svPPA or phonology (rhyming, first and last sound identification) in lvPPA [84], while orthographic cues to word production can be targeted in nfvPPA [85]. In practice, however, combined approaches have often been used [84]. Communication skills training is informed by experience in stroke aphasia and aims to enhance strategies that facilitate communication (e.g., gesture) while avoiding communication barriers (e.g., interruptions, abrupt topic changes). Augmentative and alternative communication devices may help patients with nfvPPA and limited verbal output, but preserved comprehension [86]. Adapting everyday technology such as smartphones and total communication strategies incorporating photos and pictures may enable continuation of daily activities such as shopping or cooking [87, 88]. Unfortunately, gains from non-pharmacological therapies are usually modest and there is little evidence for generalisation of effects or lasting benefit in daily life [83, 84]. It is important that new approaches continue to be developed and are assessed in adequately powered and controlled studies, with a view to a future where cognitive rehabilitation may be deployed in conjunction with disease modifying pharmacotherapy.

Pharmacological interventions

There are currently no disease modifying treatments for PPA and evidence for efficacy of symptomatic treatments is scant. We have a low threshold for trying a cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine in patients with lvPPA and nfvPPA (where Alzheimer’s pathology is a consideration), though any benefit is usually modest and care is needed to avoid exacerbating behavioural symptoms [89, 90]. Memantine appears to be well-tolerated in svPPA and nfvPPA, but clear evidence of benefit is lacking [91]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors should be considered in patients with comorbid depression or anxiety and may help to settle behavioural symptoms such as impulsivity and aggression, particularly in svPPA [92]. Newer generation neuroleptics may be indicated to manage severe agitation or psychotic symptoms later in the illness.

Conclusions and future directions

Recognition of the major PPA syndromes has transformed our understanding of the language system and given us a new picture of selective neural vulnerability in degenerative brain disease. However, this dramatic progress should not obscure the many remaining difficulties surrounding these conditions. Ultimately, effective treatment of PPA will depend on both earlier and more accurate diagnosis (improved syndrome characterisation), more accurate disease and disability staging and identification of new biomarkers that can target tissue pathology and track therapeutic effects dynamically, in advance of irrecoverable brain atrophy (improved signalling of underlying proteinopathy [93]). A successful PPA biomarker will need to encompass substantial individual variation within syndromic categories (see, e.g., Table 3).

To realise these ambitions may require a reformulation of the ‘language-led dementias’ in more fundamental, pathophysiological terms. Emerging evidence suggests that generic disorders of nonverbal auditory information processing may underpin the canonical PPA syndromes [40, 94,95,96] and that these syndromes may further be stratified by profiles of autonomic reactivity to emotional and other salient stimuli [61, 97, 98]. This evidence dovetails with the recent finding that implicit auditory sequence learning is retained in nfvPPA [99]. Such observations could motivate novel biomarkers and treatment strategies that do not depend on specific language capacities (a practical advantage in mounting large-scale, international trials in PPA). There is currently considerable interest in the application of molecular ligand neuroimaging techniques (including new tracers that can demonstrate tissue deposition of pathogenic proteins other than beta-amyloid) in PPA and other dementias [100]. Such techniques promise to delineate proteinopathies in vivo more reliably than is currently feasible; multivariate approaches combining ligand imaging with pathophysiological indices may constitute a powerful and dynamic signal of the underlying disease. Finally, more work is needed to establish rational retraining and functional rehabilitation interventions in PPA: in future, such interventions may amplify disease modifying therapies and bridge the gap from clinic to patients’ wider lives.

References

Grossman M (2010) Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol 6:88–97

Mesulam M, Rogalski E, Wieneke C, Hurley R, Geula C, Bigio E et al (2014) Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol 10:554–569

Magnin E, Démonet JF, Wallon D, Dumurgier J, Troussière AC, Jager A et al (2016) Primary progressive aphasia in the network of French Alzheimer Plan memory centers. JAlzDis 54:1459–1471

Coyle-Gilchrist IT, Dick KM, Patterson K, Vázquez Rodríquez P, Wehmann E, Wilcox A et al (2016) Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology 86:1736–1743

Pick A (1973) Aphasia (transl Brown JW). Charles C. Thomas, Springfield

Warrington EK (1975) The selective impairment of semantic memory. Q J Exp Psychol 27:635–657

Mesulam M (1982) Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann Neurol 11:592–598

Warren JD, Rohrer JD, Schott JM, Fox NC, Hardy J, Rossor MN (2013) Molecular nexopathies: a new paradigm of neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci 36:561–569

Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF et al (2011) Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76:1006–1014

Rohrer JD, Knight WD, Warren JE, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD (2008) Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias. Brain 131:8–38

Rohrer JD, Rossor MN, Warren JD (2010) Syndromes of nonfluent primary progressive aphasia: a clinical and neurolinguistic analysis. Neurology 75:603–610

Rohrer J, Lashley T, Schott J, Warren J, Mead S, Isaacs A et al (2011) Clinical and neuroanatomical signatures of tissue pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain 134:2565–2581

Sajjadi SA, Patterson K, Arnold RJ, Watson PC, Nestor PJ (2012) Primary progressive aphasia: a tale of two syndromes and the rest. Neurology 78:1670–1677

Mesulam MM, Weintraub S (2014) Is it time to revisit the classification guidelines for primary progressive aphasia? Neurology 82:1108–1109

Wicklund MR, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA (2014) Quantitative application of the primary progressive aphasia consensus criteria. Neurology 82:1119–1126

Giannini LAA, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Ash S, Rascovsky K, Wolk DA et al (2017) Clinical marker for Alzheimer disease pathology in logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 88:2276–2284

Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM (2011) Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 76:1804–1810

Wilson SM, Henry ML, Besbris M, Ogar JM, Dronkers NF, Jarrold W et al (2010) Connected speech production in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Brain 133:2069–2088

Peelle J, Troiani V, Gee J, Moore P, McMillan C, Vesely L, Grossman M (2008) Sentence comprehension and voxel-based morphometry in progressive nonfluent aphasia, semantic dementia, and nonaphasic frontotemporal dementia. J Neuroling 21:418–432

Josephs KA, Duffy J, Strand E, Machulda M, Senjem ML, Master AV et al (2012) Characterizing a neurodegenerative syndrome: primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain 135:1522–1536

Rohrer J, Rossor M, Warren J (2010) Apraxia in progressive nonfluent aphasia. J Neurol 257:569–574

Josephs K, Duffy J, Strand E, Whitwell J, Layton K, Parisi J et al (2006) Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain 129:1385–1398

Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL et al (2014) The evolution of primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain 137:2783–2795

Marshall CR, Hardy CJ, Rossor MN, Warren JD (2016) Nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia: a distinctive clinico-anatomical syndrome. Neurology 87:e283

Sajjadi SA, Sheikh-Bahaei N, Cross J, Gillard JH, Scoffings D, Nestor PJ (2017) Can MRI visual assessment differentiate the variants of primary progressive aphasia? AJNR 38:954–960

Ghacibeh GA, Heilman KM (2003) Progressive affective aprosodia and prosoplegia. Neurology 60:1192–1194

Vitali P, Nobili F, Raiteri U, Canfora M, Rosa M, Calvini P et al (2004) Right hemispheric dysfunction in a case of pure progressive aphemia: fusion of multimodal neuroimaging. Psychiatry Res 130:97–107

Hailstone JC, Crutch SJ, Vestergaard MD, Patterson RD, Warren JD (2010) Progressive associative phonagnosia: a neuropsychological analysis. Neuropsychologia 48:1104–1114

Rohrer JD, Warren JD (2010) Phenomenology and anatomy of abnormal behaviours in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol Sci 293:35–38

Harris J, Jones M, Gall C, Richardson A, Neary D, du Plessis D et al (2016) Co-occurrence of language and behavioural change in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dem Ger Cog Dis 6:205–213

Kremen SA, Mendez MF, Tsai P-H, Teng E (2011) Extrapyramidal signs in the primary progressive aphasias. Am J Alz Dis Other Dem 26:72–77

Graff-Radford J, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Josephs KA (2012) Parkinsonian motor features distinguish the agrammatic from logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Park Rel Dis 18:890–892

Chare L, Hodges J, Leyton C, McGinley C, Tan R, Kril J et al (2014) New criteria for frontotemporal dementia syndromes: clinical and pathological diagnostic implications. JNNP 85:865–870

Rogalski E, Sridhar J, Rader B, Martersteck A, Chen K, Cobia D et al (2016) Aphasic variant of Alzheimer disease: clinical, anatomic, and genetic features. Neurology 87:1337–1343

Spinelli EG, Mandelli ML, Miller ZA, Santos-Santos MA, Wilson SM, Agosta F et al (2017) Typical and atypical pathology in primary progressive aphasia variants. Ann Neurol 81:430–443

Xiong L, Xuereb J, Spillantini M, Patterson K, Hodges J, Nestor P (2011) Clinical comparison of progressive aphasia associated with Alzheimer versus FTD-spectrum pathology. JNNP 82:254–260

Rohrer JD, Guerreiro R, Vandrovcova J, Uphill J, Reiman D, Beck J et al (2009) The heritability and genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 73:1451–1456

Heitkamp N, Schumacher R, Croot K, de Langen EG, Monsch AU, Baumann T et al (2016) A longitudinal linguistic analysis of written text production in a case of semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. J Neuroling 39:26–37

Hodges JR, Patterson K (2007) Semantic dementia: a unique clinicopathological syndrome. Lancet Neurol 6:1004–1014

Goll JC, Crutch SJ, Loo JHY, Rohrer JD, Frost C, Bamiou DE, Warren JD (2010) Non-verbal sound processing in the primary progressive aphasias. Brain 133:272–285

Omar R, Henley SM, Bartlett JW, Hailstone JC, Gordon E, Sauter DA et al (2011) The structural neuroanatomy of music emotion recognition: evidence from frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neuroimage 56:1814–1821

Omar R, Mahoney CJ, Buckley AH, Warren JD (2013) Flavour identification in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. JNNP 84:88–93

Fushimi T, Komori K, Ikeda M, Lambon Ralph MA, Patterson K (2009) The association between semantic dementia and surface dyslexia in Japanese. Neuropsychologia 47:1061–1068

Garrard P, Lambon Ralph MA, Watson PC, Powis J, Patterson K, Hodges JR (2001) Longitudinal profiles of semantic impairment for living and nonliving concepts in dementia of Alzheimer’s type. J Cogn Neurosci. 13:892–909

Lambon Ralph MA, Patterson K (2008) Generalization and differentiation in semantic memory: insights from semantic dementia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1124:61–76

Rogers TT, Lambon Ralph MA, Garrard P, Bozeat S, McClelland JL, Hodges JR et al (2004) Structure and deterioration of semantic memory: a neuropsychological and computational investigation. Psychol Rev 111:205–235

Lambon Ralph MA, Jefferies E, Patterson K, Rogers TT (2017) The neural and computational bases of semantic cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 18:42–55

Chan D, Fox NC, Scahill RI, Crum WR, Whitwell JL, Leschziner G et al (2001) Patterns of temporal lobe atrophy in semantic dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 49:433–442

Rohrer JD, McNaught E, Foster J, Clegg SL, Barnes J, Omar R et al (2008) Tracking progression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: serial MRI in semantic dementia. Neurology 71:1445–1451

Kumfor F, Landin-Romero R, Devenney E, Hutchings R, Grasso R, Hodges JR et al (2016) On the right side? A longitudinal study of left- versus right-lateralized semantic dementia. Brain 139:986–998

Chan D, Anderson V, Pijnenburg Y, Whitwell J, Barnes J, Scahill R et al (2009) The clinical profile of right temporal lobe atrophy. Brain 132:1287–1298

Thompson SA, Patterson K, Hodges JR (2003) Left/right asymmetry of atrophy in semantic dementia: behavioral-cognitive implications. Neurology 61:1196–1203

Snowden JS, Bathgate D, Varma A, Blackshaw A, Gibbons ZC, Neary D (2001) Distinct behavioural profiles in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. JNNP 70:323–332

Hsieh S, Irish M, Daveson N, Hodges JR, Piguet O (2013) When one loses empathy. J Ger Psychiatry Neurol 26:174–184

Rankin KP, Kramer JH, Miller BL (2005) Patterns of cognitive and emotional empathy in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Cog Behav Neurol 18:28–36

Clark CN, Warren JD (2016) Emotional caricatures in frontotemporal dementia. Cortex 76:134–136

Clark CN, Nicholas JM, Gordon E, Golden HL, Cohen MH, Woodward FJ et al (2016) Altered sense of humor in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 49:111–119

Fletcher PD, Downey LE, Golden HL, Clark CN, Slattery CF, Paterson RW et al (2015) Pain and temperature processing in dementia: a clinical and neuroanatomical analysis. Brain 138:3360–3372

Fletcher PD, Downey LE, Golden HL, Clark CN, Slattery CF, Paterson RW et al (2015) Auditory hedonic phenotypes in dementia: a behavioural and neuroanatomical analysis. Cortex 67:95–105

Midorikawa A, Kumfor F, Leyton CE, Foxe D, Landin-Romero R, Hodges JR et al (2017) Characterisation of “positive” behaviours in primary progressive aphasias. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 44:119–128

Marshall CR, Hardy CJD, Russell LL, Clark CN, Dick KM, Brotherhood EV et al (2017) Impaired interoceptive accuracy in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. Front Neurol 8:610

Irish M, Addis DR, Hodges JR, Piguet O (2012) Considering the role of semantic memory in episodic future thinking: evidence from semantic dementia. Brain 135:2178–2191

Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Murray ME, Parisi JE, Graff-Radford NR, Knopman DS et al (2013) Corticospinal tract degeneration associated with TDP-43 type C pathology and semantic dementia. Brain 136:455–470

Caroppo P, Camuzat A, De Septenville A, Couratier P, Lacomblez L, Auriacombe S et al (2015) Semantic and nonfluent aphasic variants, secondarily associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, are predominant frontotemporal lobar degeneration phenotypes in TBK1 carriers. Alz Dem 1:481–486

Butts AM, Machulda MM, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA (2015) Neuropsychological profiles differ among the three variants of primary progressive aphasia. JINS 21:429–435

Piguet O, Leyton CE, Gleeson LD, Hoon C, Hodges JR (2015) Memory and emotion processing performance contributes to the diagnosis of non-semantic primary progressive aphasia syndromes. J Alz Dis 44:541–547

Leyton CE, Savage S, Irish M, Schubert S, Piguet O, Ballard KJ, Hodges JR (2014) Verbal repetition in primary progressive aphasia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 41:575–585

Rohrer JD, Ridgway GR, Crutch SJ, Hailstone J, Goll JC, Clarkson MJ et al (2010) Progressive logopenic/phonological aphasia: erosion of the language network. NeuroImage 49:984–993

Spitsyna G, Warren JE, Scott SK, Turkheimer FE, Wise RJ (2006) Converging language streams in the human temporal lobe. J Neurosci 26:7328–7336

Henry ML, Gorno-Tempini ML (2010) The logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Curr Opin Neurol 23:633–637

Magnin E, Chopard G, Ferreira S, Sylvestre G, Dariel E, Ryff I et al (2013) Initial neuropsychological profile of a series of 20 patients with logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. J Alz Dis 36:799–808

Matías-Guiu JA, Cabrera-Martín MN, Moreno-Ramos T, Valles-Salgado M, Fernandez-Matarrubia M, Carreras JL, Matías-Guiu J (2015) Amyloid and FDG-PET study of logopenic primary progressive aphasia: evidence for the existence of two subtypes. J Neurol 262:1463–1472

Leyton CE, Hodges JR, McLean CA, Kril JJ, Piguet O, Ballard KJ (2015) Is the logopenic-variant of primary progressive aphasia a unitary disorder? Cortex 67:122–133

Goll JC, Ridgway GR, Crutch SJ, Theunissen FE, Warren JD (2012) Nonverbal sound processing in semantic dementia: a functional MRI study. NeuroImage 61:170–180

Hardy CJD, Agustus JL, Marshall CR, Clark CN, Russell LL, Brotherhood EV et al (2017) Functional neuroanatomy of speech signal decoding in primary progressive aphasias. Neurobiol Aging 56:190–201

Rossor M, Warrington EK, Cipolotti L (1995) The isolation of calculation skills. J Neurol 242:78–81

Hardy CJ, Buckley AH, Downey LE, Lehmann M, Zimmerer VC, Varley RA et al (2016) The language profile of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. J Alz Dis 50:359–371

Ahmed S, de Jager CA, Haigh AM, Garrard P (2012) Logopenic aphasia in Alzheimer’s disease: clinical variant or clinical feature? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83:1056–1062

Mendez MF (2017) Non-neurogenic language disorders: a preliminary classification. Psychosomatics. pii: S0033-3182(17)30182-2

Luzzi S, Viticchi G, Piccirilli M, Fabi K, Pesallaccia M, Bartolini M et al (2008) Foreign accent syndrome as the initial sign of primary progressive aphasia. JNNP 79:79–81

Confavreux C, Croisile B, Garassus P, Aimard G, Trillet M (1992) Progressive amusia and aprosody. Arch Neurol 49:971–976

Volkmer A (2013) Assessment and therapy for language and cognitive communication difficulties in dementia and other progressive diseases. JR Press, North Guilford

Carthery-Goulart MT, da Silveira AC, Machado TH, Mansur LL, Parente MAMP, Senaha MLH et al (2013) Nonpharmacological interventions for cognitive impairments following primary progressive aphasia: a systematic review of the literature. Dem Neuropsychol 7:122–131

Jokel R, Graham NL, Rochon E, Leonard C (2014) Word retrieval therapies in primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiol 28:1038–1068

Henry ML, Meese MV, Truong S, Babiak MC, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML (2013) Treatment for apraxia of speech in nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia. Behav Neurol 26:77–88

Pattee C, Von Berg S, Ghezzi P (2006) Effects of alternative communication on the communicative effectiveness of an individual with a progressive language disorder. Int J Rehab Res 29:151–153

Wong SB, Anand R, Chapman SB, Rackley A, Zientz J (2009) When nouns and verbs degrade: facilitating communication in semantic dementia. Aphasiology 23:286–301

Bier N, Brambati S, Macoir J, Paquette G, Schmitz X, Belleville S et al (2015) Relying on procedural memory to enhance independence in daily living activities: smartphone use in a case of semantic dementia. Neuropsychol Rehab 25:913–935

Kertesz A, Morlog D, Light M, Blair M, Davidson W, Jesso S, Brashear R (2008) Galantamine in frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25:178–185

Kaye ED, Petrovic-Poljak A, Verhoeff NP, Freedman M (2010) Frontotemporal dementia and pharmacologic interventions. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 22:19–29

Boxer AL, Lipton AM, Womack K, Merrilees J, Neuhaus J, Pavlic D et al (2009) An open-label study of memantine treatment in 3 subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23:211–217

Prodan CI, Monnot M, Ross ED (2009) Behavioural abnormalities associated with rapid deterioration of language functions in semantic dementia respond to sertraline. JNNP 80:1416–1417

Dickerson BC (2011) Quantitating severity and progression in primary progressive aphasia. J Mol Neurosci 45:618–628

Goll JC, Kim LG, Hailstone JC, Lehmann M, Buckley A, Crutch SJ, Warren JD (2011) Auditory object cognition in dementia. Neuropsychologia 49:2755–2765

Grube M, Bruffaerts R, Schaeverbeke J, Neyens V, De Weer A-S, Seghers A et al (2016) Core auditory processing deficits in primary progressive aphasia. Brain 139:1817–1829

Hardy CJD, Agustus JL, Marshall CR, Clark CN, Russell LL, Bond RL et al (2017) Behavioural and neuroanatomical correlates of auditory speech analysis in primary progressive aphasias. Alzheimers Res Ther 9:53

Fletcher PD, Nicholas JM, Shakespeare TJ, Downey LE, Golden HL, Agustus JL et al (2015) Physiological phenotyping of dementias using emotional sounds. Alz Dem 1:170–178

Fletcher PD, Nicholas JM, Shakespeare TJ et al (2015) Dementias show differential physiological responses to salient sounds. Front Behav Neurosci 9:73

Cope TE, Wilson B, Robson H, Drinkall R, Dean L, Grube M et al (2017) Artificial grammar learning in vascular and progressive non-fluent aphasias. Neuropsychologia 104:201–213

Bevan-Jones WR, Cope TE, Jones PS, Passamonti L, Hong YT, Fryer TD et al (2017) 18F]AV-1451 binding in vivo mirrors the expected distribution of TDP-43 pathology in the semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry in press. pii: jnnp-2017-316402

Snowden JS, Kindell J, Thompson JC, Richardson AM, Neary D (2012) Progressive aphasia presenting with deep dyslexia and dysgraphia. Cortex 48:1234–1239

Warren JD, Warren JE, Fox NC, Warrington EK (2003) Nothing to say, something to sing: primary progressive dynamic aphasia. Neurocase 9:140–155

Ingles JL, Fisk JD, Passmore M, Darvesh S (2007) Progressive anomia without semantic or phonological impairment. Cortex 43:558–564

Otsuki M, Soma Y, Sato M, Homma A, Tsuji S (1998) Slowly progressive pure word deafness. Eur Neurol 39:135–140

Warren JD, Hardy CJ, Fletcher PD, Marshall CR, Clark CN, Rohrer JD, Rossor MN (2016) Binary reversals in primary progressive aphasia. Cortex 82:287–289

Rohrer JD, Warren JD, Rossor MN (2009) Abnormal laughter-like vocalisations replacing speech in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol Sci 284:120–123

Thompson CK, Lukic S, King MC, Mesulam MM, Weintraub S (2012) Verb and noun deficits in stroke-induced and primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiol 26:632–655

Rohrer JD, Sauter D, Scott S, Rossor MN, Warren JD (2012) Receptive prosody in nonfluent primary progressive aphasias. Cortex 48:308–316

Hailstone JC, Ridgway GR, Bartlett JW, Goll JC, Crutch SJ, Warren JD (2012) Accent processing in dementia. Neuropsychologia 50:2233–2244

Hardy CJD, Marshall CR, Golden HL, Clark CN, Mummery CJ, Griffiths TD et al (2016) Hearing and dementia. J Neurol 263:2339–2354

Mahoney CJ, Rohrer JD, Goll JC, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD (2011) Structural neuroanatomy of tinnitus and hyperacusis in semantic dementia. JNNP 82:1274–1278

Cipolotti L, Maguire EA (2003) A combined neuropsychological and neuroimaging study of topographical and non-verbal memory in semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia 41:1148–1159

Papagno C, Semenza C, Girelli L (2013) Meeting an “impossible challenge” in semantic dementia: outstanding performance in numerical Sudoku and quantitative number knowledge. Neuropsychology 27:680–690

Hailstone JC, Omar R, Warren JD (2009) Relatively preserved knowledge of music in semantic dementia. JNNP 80:808–809

Ueno T, Lambon Ralph MA (2013) The roles of the “ventral” semantic and “dorsal” pathways in conduite d’approche: a neuroanatomically-constrained computational modeling investigation. Front Hum Neurosci 7:422

Rohrer JD, Rossor MN, Warren JD (2009) Neologistic jargon aphasia and agraphia in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol Sci 277:155–159

Caffarra P, Gardini S, Cappa S, Dieci F, Concari L, Barocco F et al (2013) Degenerative jargon aphasia: unusual progression of logopenic progressive aphasia? Behav Neurol 26:89–93

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Thomas Cope, Prof. Chris Butler and Prof. Tim Griffiths for helpful discussion. The Dementia Research Centre is supported by Alzheimer’s Research UK, the Brain Research Trust, and the Wolfson Foundation. This work was supported by the Alzheimer’s Society (AS-PG-16-007), the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre and the UCL Leonard Wolfson Experimental Neurology Centre (PR/ylr/18575). Individual authors were supported by the Leonard Wolfson Foundation (Clinical Research Fellowship to CRM), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Doctoral Training Fellowship to AV), the National Brain Appeal–Frontotemporal Dementia Research Fund (CNC) and the Medical Research Council (PhD Studentships to CJDH and RLB, MRC Research Training Fellowship to PDF, MRC Clinician Scientist to JDR). MNR and NCF are NIHR Senior Investigators. SJC is supported by Grants from ESRC-NIHR (ES/L001810/1), EPSRC (EP/M006093/1) and Wellcome Trust (200783). JDW was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Clinical Science (091673/Z/10/Z).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marshall, C.R., Hardy, C.J.D., Volkmer, A. et al. Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. J Neurol 265, 1474–1490 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6