Abstract

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) and other chronic tic disorders are neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by the presence of tics and associated behavioral problems. Whilst converging evidence indicates that these conditions can affect patients’ quality of life (QoL), the extent of this impairment across the lifespan is not well understood. We conducted a systematic literature review of published QoL studies in GTS and other chronic tic disorders to comprehensively assess the effects of these conditions on QoL in different age groups. We found that QoL can be perceived differently by child and adult patients, especially with regard to the reciprocal contributions of tics and behavioral problems to the different domains of QoL. Specifically, QoL profiles in children often reflect the impact of co-morbid attention-deficit and hyperactivity symptoms, which tend to improve with age, whereas adults’ perception of QoL seems to be more strongly affected by the presence of depression and anxiety. Management strategies should take into account differences in age-related QoL needs between children and adults with GTS or other chronic tic disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic tic disorders encompass a continuum of childhood-onset neurodevelopmental conditions, ranging from the more severe Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) to chronic motor or vocal tic disorder. GTS is characterized by multiple motor and vocal/phonic tics which affects 0.3–1 % of the general population and is 3–4 times more common in males [1]. Tics are defined as sudden, rapid, non-rhythmic, involuntary movements (motor tics) or vocalizations (phonic tics); although there is typically a peak in severity in early adolescence, tics tend to vary in frequency and severity throughout life [2]. Despite empirically validated treatment strategies, a considerable proportion of patients irrespective of age fail to respond to either behavior therapy or pharmacological treatment and continue to experience significant symptom burden throughout life [3]. GTS is recognized as a complex disorder, being associated with co-morbid conditions such as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety and affective disorders in around 90 % of patients according to both clinical and community studies [4–7].

Patients with GTS and other chronic tic disorders perceive their quality of life (QoL) as poorer than that of healthy individuals [8–11]. Understandably, both the direct consequences of tic expression and the efforts related to their suppression can present a functional burden for those affected. Moreover, research conducted over the last 15 years has highlighted that the presence of co-morbid behavioral problems can also be associated with poorer QoL, particularly in children [12]. However, evidence regarding the role played by tic severity or the specific QoL domains which are mostly affected has been inconsistent [13–17], partly due to the considerable variability in the instruments used to assess QoL throughout the years. Generic QoL measures are unlikely to be sensitive to specific features which are central to the perceived well-being of patients with GTS and other chronic tic disorders, and the recent introduction of a disease-specific instrument (GTS-QOL) facilitated the development of a fruitful line of research in this field [18–20].

While current evidence suggests that severity and frequency of tics may decline after childhood, the knowledge gap on determinants of QoL in GTS and other chronic tic disorders has been only partially filled by focused research in recent years [12]. Moreover, the differing natural course of tics and co-morbid behavioral symptoms can complicate the evolving picture of QoL in patients with these conditions [21–23]. An improved understanding of the specific domains of QoL which are affected throughout the lifespan will provide important information for strategic prioritization in clinical practice and resource allocation by healthcare providers in pediatric versus adult setting. Knowledge about QoL trends in GTS and other chronic tic disorders across the lifespan will also provide patients with useful information about the expected long-term outcomes of their condition. We, therefore, set out to explore possible differences in QoL domains across different age groups of patients with GTS and other chronic tic disorders by comprehensively reviewing the existing literature.

Methods

The present systematic review was conducted in accordance with the methodology outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) consensus statement [24]. Three electronic databases (PubMed, PsycInfo and PsycARTICLES), plus the NHS Evidence website, were searched using the following terms or MeSH headings: “Tourette”, “tic disorder”, “quality of life” and “functional impairment”. The same search terms were also used to identify relevant grey literature through Google Scholar, and the reference lists of articles which met selection criteria were manually screened for further relevant studies. All searches were restricted to publications in English language and availability of full text. Articles were not restricted by age, gender or other demographical criteria. Only studies in which patients received a formal diagnosis of GTS or other chronic tic disorders by an experienced clinician according to validated criteria were considered for inclusion. Childhood studies were defined as those with a maximum participant age of 18 years and a maximum mean age of 16 years. Studies which investigated patients with co-morbidities were considered eligible if QoL assessment was established as primary outcome measure. All studies using original quantitative research methodologies were eligible for inclusion in this review (retrospective/prospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies and case series). Intervention studies were excluded as the outcome of QoL would have been evaluated based on the efficacy of an active intervention rather than the effects of GTS itself. Qualitative research was excluded as results would not be suitably compared to quantitative data within the present review [25].

The selected studies were assessed for methodological quality prior to inclusion using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT). This instrument has shown appropriate construct validity in evaluating methodological quality and higher reliability than informal appraisal [26–28]. The properties of the CCAT allowed us to include a wide variety of study designs within the published literature [29]. Minimum standards for inclusion in our review were established following the author’s recommendations such that all appraised studies exceeded a minimum threshold quality score of 30 % [27].

Results

Our search strategy yielded a total of 57 relevant articles after duplicates were removed. A flow diagram which outlines the selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

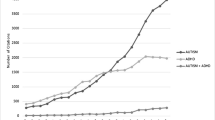

A total of 21 studies focussing on the QoL of patients with GTS or other chronic tic disorders met the inclusion criteria of this systematic review, 14 of which were conducted in children [14, 16, 17, 19, 30–39] and 7 in adults [15, 20, 40–44]. The vast majority of studies (20/21) were published during the last decade (Fig. 2).

A further 14 studies were deemed to be relevant; however, they had to be excluded due to incomplete or insufficient information [13, 18, 45–55]. The included studies were assigned a Quality Score through the standardized assessment of methodological quality, and were summarized in two separate tables according to child or adult target population (Tables 1, 2, respectively).

The different aspects of QoL assessed in the reviewed literature could be categorized according to six recurring themes or domains, i.e. physical, psychological, occupational, social, cognitive, and obsessional aspects.

Discussion

Overall findings

GTS and other chronic tic disorders are lifelong disorders which broadly impact on QoL throughout their duration. Taken together, the results of the reviewed studies indicate that the perception of QoL may change significantly with age, in parallel with the natural course of the symptoms specific to the GTS spectrum. In children, the interaction between tics and co-morbid attention-deficit and hyperactivity symptoms can have a particularly severe impact on school life, whilst also having detrimental effects on the emotional, social and physical well-being which persist into adulthood. Adult patients with GTS or other chronic tic disorders tend to report a consistent global decline in QoL as a result of the persistence of tic symptoms, despite their reduced severity; moreover, the impact of co-morbid depression and anxiety on QoL seem to become more apparent with age. It is important to recognize the likely interplay between QoL domains, whereby for example specific components of emotional well-being such as decreased self-esteem and perceived stigma are likely to result in social withdrawal.

Physical aspects

The physical domain of QoL reflected the presence of pain and injury as a direct result of tic severity. The results of the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey, a study which involved both children and adults with GTS or other chronic tic disorders, showed that the majority of respondents reported at least one tic that caused pain or physical damage (64 and 60 %, respectively), with significant correlation to reported tic severity [33, 41]. Co-morbid ADHD and OCD symptoms were shown to further affect the physical aspects of QoL, especially in children [14, 17], with few exceptions [16]. In adults, difficulties in carrying out activities of daily living, including self-care, can cause significant distress as overt manifestations of problems in functional mobility and ability to perform exercises [56]. However, the overall preliminary findings from studies using disease-specific QoL measures suggest that perception of QoL is more strongly linked to physical health in children [19, 20]. Taken together, these results confirm that the physical components of QoL should not be overlooked throughout the lifespan.

Emotional aspects

Emotional well-being is an important component of QoL classified under the psychological domain. Anxiety, feelings of frustration, hopelessness and low mood are commonly reported by patients with GTS or other chronic tic disorders and appear to be multifactorial in origin [42, 58]. A controlled study conducted in a clinical sample of children with GTS showed that anxiety and depression were significantly more prevalent than in both healthy children and patients with epilepsy [14]. Likewise, about 57 % of adult patients with GTS from a clinical sample reported problems with co-morbid anxiety and depressive symptoms, with an odds ratio of 13 compared to age-matched controls [15]. In general, psychological symptoms have been shown to be among the most important determinants of overall QoL [57], especially after the transition to adulthood [19, 20]. Interestingly, the results of the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey indicated that children were considerably less likely than adults to believe that tics had led to the development of an emotional disorder (35 versus 59 %, respectively), despite awareness of stigma and isolation [33, 41].

Occupational aspects

The negative impact of GTS and other chronic tic disorders for children in the school setting and for adults in the job environment was captured by the occupational domain of QoL. The presence of co-morbid behavioral problems, particularly ADHD, was consistently shown to affect school life [17, 30, 35] and overall QoL in children with GTS or other chronic tic disorders. The improvement of ADHD symptoms with age could contribute to explain the less pronounced impairment of QoL reported in adult working life [21, 22]. In fact, the results of the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey showed that adults report milder interference with work productivity compared to the level of academic interference noted by children with GTS or other chronic tic disorders [33, 41]. Although the development of coping strategies throughout adolescence can subsequently result in improved satisfaction with life in the workplace [59], bullying and other distressing school experiences can have far-reaching consequences, possibly influencing future job choice and/or employment status [60, 61].

Social aspects

Relationships with family and friends are key components of the social domain of QoL. Specifically, healthy family functioning has been recognized as integral to long-term social and emotional stability in children with GTS [62]. It has been shown that younger patients with tics can often feel responsible for family arguments as a result of their condition, and can be more likely to avoid communication with their parents [14, 16, 36], possibly resulting in increased insecurity and exacerbated problems over time [36]. Patients of all ages have reported higher interference from GTS and other chronic tic disorders within peer friendships than family relationships [33, 41], with potential difficulties in the formation of intimate or meaningful relationships which are an important part of adult life [42]; however, one study on adult patients showed that 29 % of participants felt unsupported by their family about their condition [40]. Although co-morbid depressive symptoms, emotional lability and anxiety were all identified as features of GTS and other chronic tic disorders potentially resulting in problems with social functioning [37, 57], the full extent of the impact of behavioral co-morbidities on social aspects of QoL remains difficult to determine, particularly in the case of adults with co-morbid OCD [12, 23].

Cognitive aspects

Problems with concentration, forgetfulness and inability to complete important tasks encompass the cognitive domain of QoL. Interestingly, improvement of co-morbid ADHD symptoms with age seems to have a more significant impact on occupational than cognitive aspects of QoL [21]. A significant correlation between tic severity and cognitive domain scores was highlighted by the findings of the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey [41]. Moreover, Studies conducted using the GTS-QOL further suggested that QoL perception can be more deeply affected by cognitive factors in adulthood than in childhood [19, 20]. These findings suggest that the interaction between tics and cognitive function in determining QoL across the lifespan is more complex than expected and deserves further investigation in future studies.

Obsessional aspects

The development of disease-specific QoL measures for patients with GTS has enabled researchers to more sensitively assess the impact of repetitive behaviours and co-morbid OCD symptoms on the overall perception of QoL [19, 20]. Studies that have used the GTS-QOL report a decrease in the perceived impact of OCD on QoL from childhood to adulthood, despite the absence of clinically relevant decreases in OCD symptom severity, possibly reflecting the development of more effective coping strategies over time [34, 43]. Overall, disease-specific measures allow to more sensitively address the core symptoms of GTS and other chronic tic disorders compared to the generic measures that were used in 19 out of the 21 reviewed studies [63, 64].

Methodological issues

In addition to the variability in study quality and research methodology, the reviewed literature contained a number of limitations that need to be taken into consideration when attempting to draw any conclusion. Participants in the reviewed studies were commonly recruited from tertiary referral centres, which usually recruit more severe and complex cases with a higher incidence of co-morbidities. This referral bias may limit the generalizability of the findings on the influence of GTS and other chronic tic disorders on QoL to the wider community of patients with these conditions. Moreover, there were inconsistencies in reporting self and proxy ratings of QoL in children with GTS and other chronic tic disorders, as well as co-morbidity rates across the lifespan. Specifically, in some studies parent-reported QoL was different from child reports [30, 65], raising the possibility that parent ratings might not capture the full extent of the effects of tics on the child’s QoL, especially with regard to subjective aspects. For example, none of the three reviewed studies that examined QoL of children with tic disorders by parent reports only demonstrated any deterioration in the psychological component of QoL [16, 17, 35]. Moreover, the role of treatment interventions for tics should be taken into account, as it can mitigate the impact of tic severity on QoL. For example, in the study by Bernard et al. [17], 39 % of the participants were receiving medication for their tics and tics were generally assessed to be under good control. Finally, our search methodology might have led to the exclusion of potentially relevant studies because of language or availability, resulting in reporting biases within the review process.

Conclusions

The wide-ranging impact of GTS and other chronic tic disorders on the QoL of patients of all ages has been investigated in a number of dedicated studies since the new millennium. Research has mainly focused on the impact of tic symptoms and co-morbid behavioral problems on different QoL domains, which are characterized by varying degrees of functional overlap and potential interactions. Differences in QoL perception between children and adults suggest that a tailored approach could be the most fruitful strategy for the management of GTS and other chronic tic disorders across the lifespan. Future research using a longitudinal design is needed to further explore the natural history of tic disorders and associated behavioral co-morbidities, to determine their changing impact on QoL during the transition from childhood to adulthood. Finally, the use of disease-specific QoL measures in future studies will enable better understanding of QoL profiles in both clinic and community samples of patients with GTS and other chronic tic disorders.

References

Cavanna AE, Termine C (2012) Tourette syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol 724:375–383

Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L et al (2000) An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3500 individuals in 22 countries. Dev Med Child Neurol 42:436–447

Frank M, Cavanna AE (2013) Behavioural treatments for Tourette syndrome: an evidence-based review. Behav Neurol 27:105–117

Cavanna AE, Servo S, Monaco F et al (2009) The behavioral spectrum of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 21:13–23

Robertson MM (2000) Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment. Brain 123:425–462

Khalifa N, von Knorring AL (2005) Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders in a total population of children: clinical assessment and background. Acta Paediatr 94:1608–1614

Mol Debes NM, Hjalgrim H, Skov L (2008) Validation of the presence of comorbidities in a Danish clinical cohort of children with Tourette syndrome. J Child Neurol 23:1017–1027

Erenberg G, Cruse RP, Rothner AD (1987) The natural history of Tourette syndrome: a follow-up study. Ann Neurol 22:383–385

Grossman HY, Mostofsky DI, Harrison RH (1986) Psychological aspects of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. J Clin Psychol 42:228–235

Smith H, Fox JRE, Trayner P (2015) The lived experiences of individuals with Tourette syndrome or tic disorders: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Br J Psychol 106:609–634

Hassan N, Cavanna AE (2012) The prognosis of Tourette syndrome: implications for clinical practice. Funct Neurol 27:23–27

Cavanna AE, David K, Bandera V et al (2013) Health-related quality of life in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a decade of research. Behav Neurol 27:83–93

Eddy CM, Cavanna AE, Gulisano M et al (2011) Clinical correlates of quality of life in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord 26:735–738

Eddy CM, Rizzo R, Gulisano M et al (2011) Quality of life in young people with Tourette syndrome: a controlled study. J Neurol 258:291–301

Müller-Vahl K, Dodel I, Muller N et al (2010) Health-related quality of life in patients with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. Mov Disord 25:309–314

Pringsheim T, Lang A, Kurlan R et al (2009) Understanding disability in Tourette syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 51:468–472

Bernard BA, Stebbins GT, Siegel S et al (2009) Determinants of quality of life in children with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord 24:1070–1073

Cavanna AE, Luoni C, Selvini C et al (2013) Disease-specific quality of life in young patients with Tourette syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 48:111–114

Cavanna AE, Luoni C, Selvini C et al (2013) The Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome-Quality of Life Scale for children and adolescents (C&A-GTS-QOL): development and validation of the Italian version. Behav Neurol 27:95–103

Cavanna AE, Schrag A, Morley D et al (2008) The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome-quality of life scale (GTS-QOL): development and validation. Neurology 71:1410–1416

Haddad AD, Umoh G, Bhatia V et al (2009) Adults with Tourette’s syndrome with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 120:299–307

Robertson MM (2006) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tics and Tourette’s syndrome: the relationship and treatment implications. A commentary. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 15:1–11

Eddy CM, Cavanna AE (2014) Tourette syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder: compulsivity along the continuum. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 3:363–371

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1006–1012

Goldsmith MR, Bankhead CR, Austoker J (2007) Synthesising quantitative and qualitative research in evidence-based patient information. J Epidemiol Community Health 61:262–270

Crowe M, Sheppard L (2011) A general critical appraisal tool: an evaluation of construct validity. Int J Nurs Stud 48:1505–1516

Crowe M, Sheppard L, Campbell A (2011) Comparison of the effects of using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool versus informal appraisal in assessing health research: a randomised trial. Int J Evid Based Healthc 9:444–449

Crowe M, Sheppard L, Campbell A (2012) Reliability analysis for a proposed critical appraisal tool demonstrated value for diverse research designs. J Clin Epidemiol 65:375–383

Crowe M, Sheppard L (2011) A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: alternative tool structure is proposed. J Clin Epidemiol 64:79–89

Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Lack C et al (2007) Quality of life in youth with Tourette’s syndrome and chronic tic disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36:217–227

Cutler D, Murphy T, Gilmour J et al (2009) The quality of life of young people with Tourette syndrome. Child Care Health Dev 35:496–504

Hao Y, Tian Q, Lu Y et al (2010) Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core scales. Qual Life Res 19:1229–1233

Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH et al (2011) Exploring the impact of chronic tic disorders on youth: results from the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 42:219–242

Rizzo R, Gulisano M, Cali PV et al (2012) Long term clinical course of Tourette syndrome. Brain Dev 34:667–673

Cavanna AE, Luoni C, Selvini C et al (2013) Parent and self-report health-related quality of life measures in young patients with Tourette syndrome. J Child Neurol 28:1305–1308

Liu S, Zheng L, Zheng X et al (2015) The subjective quality of life in young people with Tourette syndrome in China. J Atten Disord (in press)

Rizzo R, Gulisano M, Pellico A et al (2014) Tourette syndrome and comorbid conditions: a spectrum of different severities and complexities. J Child Neurol 29:1383–1389

McGuire JF, Park JM, Wu MS et al (2014) The impact of tic severity dimensions on impairment and quality of life among youth with chronic tic disorders. Children’s Health Care 44:277–292

Gutierrez-Colina AM, Eaton CK, Lee JL (2015) Health-related quality of life and psychosocial functioning in children with Tourette syndrome: parent-child agreement and comparison to healthy norms. J Child Neurol 30:326–332

Elstner K, Selai CE, Trimble MR et al (2001) Quality of Life (QOL) of patients with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 103:52–59

Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH et al (2013) The impact of Tourette Syndrome in adults: results from the Tourette syndrome impact survey. Community Ment Health J 49:110–120

Jalenques I, Galland F, Malet L et al (2012) Quality of life in adults with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. BMC Psychiatry 12:109

Cavanna AE, David K, Orth M et al (2012) Predictors during childhood of future health-related quality of life in adults with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 16:605–612

Crossley E, Cavanna AE (2013) Sensory phenomena: clinical correlates and impact on quality of life in adult patients with Tourette syndrome. Psychiatry Res 209:705–710

Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Zhang H (2003) Disruptive behavior in children with Tourette’s syndrome: association with ADHD comorbidity, tic severity, and functional impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:98–105

Storch EA, Lack CW, Simons LE et al (2007) A measure of functional impairment in youth with Tourette’s syndrome. J Pediatr Psychol 32:950–959

Marek E (2007) Social functioning and quality of life for individuals with Tourette’s syndrome. Dissertation Abstracts International 68(4-B)

Eddy CM, Cavanna AE, Gulisano M et al (2012) The effects of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on quality of life in Tourette syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 24:458–462

Sukhodolsky DG, Eicher G, Leckman JF (2013) Social and adaptive functioning in Tourette syndrome. In: Martino D, Leckman JF (eds) Tourette syndrome. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 468–486

McGuire JF, Hanks C, Lewin AB et al (2013) Social deficits in children with chronic tic disorders: phenomenology, clinical correlates and quality of life. Compr Psychiatry 54:1023–1031

Hoekstra PJ, Lundervold AJ, Lie SA et al (2013) Emotional development in children with tics: a longitudinal population-based study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22:185–192

Espil FM, Capriotti MR, Conelea CA et al (2014) The role of parental perceptions of tic frequency and intensity in predicting tic-related functional impairment in youth with chronic tic disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45:657–665

Eddy CM, Cavanna AE (2013) Premonitory urges in adults with complicated and uncomplicated Tourette syndrome. Behav Modif 38:264–275

Dehning S, Leitner B, Schennach R et al (2014) Functional outcome and quality of life in Tourette’s syndrome after deep brain stimulation of the posteroventrolateral globus pallidus internus: long-term follow-up. World J Biol Psychiatry 15:66–75

McGuire JF, Arnold E, Park JM et al (2015) Living with tics: reduced impairment and improved quality of life for youth with chronic tic disorders. Psychiatry Res 225:571–579

Parisi JM (2010) Engagement in adulthood: perceptions and participation in daily activities. Act Adapt Aging 34:1–16

Lewin AB, Storch EA, Conelea CA et al (2011) The roles of anxiety and depression in connecting tic severity and functional impairment. J Anxiety Disord 25:164–168

Schrag A, Selai C, Quinn N et al (2006) Measuring quality of life in PSP: the PSP-QoL. Neurology 67:39–44

Wadman R, Tischler V, Jackson GM (2013) ‘Everybody just thinks I’m weird’: a qualitative exploration of the psychosocial experiences of adolescents with Tourette syndrome. Child Care Health Dev 39:880–886

Shady G, Boroder R, Staley D et al (1995) Tourette syndrome and employment: descriptors, predictors, and problems. Psychiatr Rehabil J 19:35–42

Zinner SH, Conelea CA, Glew GM et al (2012) Peer victimization in youth with Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 43:124–136

Carter AS, O’Donnell DA, Schultz RT et al (2000) Social and emotional adjustment in children affected with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome: associations with ADHD and family functioning. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41:215–223

Solans M, Pane S, Estrada MD et al (2008) Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: a systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health 11:742–764

Conelea CA, Busch AM, Catanzaro MA et al (2014) Tic-related activity restriction as a predictor of emotional functioning and quality of life. Compr Psychiatry 55:123–129

Hesapçıoğlu ST, Tural MK, Kandil S (2014) Quality of life and self-esteem in children with chronic tic disorder. Turk Pediatri Ars 49:323–332

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, J., Seri, S. & Cavanna, A.E. The effects of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders on quality of life across the lifespan: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25, 939–948 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0823-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0823-8