Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical spectrum of peripartum tuberculosis from the perspective of immunorestitution disease. Of 29 patients with peripartum tuberculosis, 27 (93.1%) had extrapulmonary tuberculosis, 20 (69%) of whom were affected in the central nervous system. Twenty-two (75.9%) patients had no clinical features suggestive of tuberculosis during pregnancy. The median time from delivery to the onset of immunorestitution was 4 days, but treatment with anti-tuberculous therapy was delayed for a median time of 27 days after the onset of symptoms. Despite therapy, 11 (38%) patients died and 4 (13.8%) had residual functional deficits. Peripartum tuberculosis is an important differential diagnosis of postpartum fever (of unknown origin) without localized signs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of tuberculosis during pregnancy is increasing in both developed and developing countries, especially in the era of HIV coinfection [1]. Tuberculosis is well known to be associated with immunorestitution disease in HIV-positive patients, in whom rebound immunopathological damage may occur during the reversal of immunosuppression, achieved by a reduction in the HIV viral load and a recovery of CD4+ lymphocyte counts following initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy [2]. In addition, paradoxical response during antituberculous therapy has been reported in HIV-negative patients [3].

Pregnancy is an immunosuppressive process to avoid maternal rejection of the fetus. Selective suppression of cell-mediated immunity and progressive impairment of lymphocytic reactivity towards the purified protein derivative of tuberculin during pregnancy have been documented [4]. After delivery of the baby, a rebound lymphocytic proliferative response was reported as early as 24 h after delivery [4]. Therefore, it is not surprising to observe an increase in the severity of symptoms of tuberculosis in the postpartum period. In this report, we describe two patients with peripartum tuberculosis from the perspective of immunorestitution disease and review the literature on this topic.

Materials and Methods

For the purpose of this study, peripartum tuberculosis is defined as an acute deterioration or worsening of clinical symptoms of pre-existing tuberculosis during pregnancy or the onset of clinical symptoms attributable to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection within 1 month of delivery. Mycobacterium tuberculosis can be present latently or symptomatically during pregnancy. The time to development of tuberculosis is defined as the interval between delivery and the onset of clinical symptoms and signs or radiological appearance of tuberculosis.

The English-language literature (1966–2002) was searched using the Medline databases of the National Library of Medicine. The keywords of tuberculosis, tuberculous, peripartum, puerperium and postpartum were used to select the cases listed in Table 1. All case reports and clinical studies that provided full clinical details were included in this study if they fit the definition of peripartum tuberculosis. The bibliographies cited were also retrieved for further analysis where appropriate. Two patients with peripartum tuberculosis managed in our center were also reported.

Results and Discussion

Case 1 was a 36-year-old woman admitted to hospital because of fever of 5 days' duration at 22 weeks of gestation. She had no pulmonary symptoms, and no focus of infection was identified. Her leukocyte count was normal, but the differential count revealed lymphopenia of 300 cells/µl. The liver function test was abnormal. Laboratory investigations for sepsis and ultrasound examination of the pelvic region were unremarkable. Intravenous cefuroxime 750 mg q8 h was started on day 2 of admission. A chest radiograph obtained on day 5 was normal. Mantoux test was performed on day 10, but no induration was detected.

On day 12 the patient delivered a stillborn fetus vaginally. Eleven hours after delivery of the fetus, she went into septic shock and respiratory distress, requiring mechanical ventilation and intensive care support. She was given intravenous ceftazidime and metronidazole as empirical therapy. The chest radiograph revealed bilateral nodular opacities. A review of serial chest radiographs showed miliary shadowing in both midzones and lower zones on the chest radiograph taken on day 5, which progressed rapidly on the day of delivery (day 12), day 13, and day 21. A clinical diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis was made. On day 21, antituberulous therapy was initiated with oral isoniazid 300 mg/day, rifampicin 600 mg/day, ethambutol 700 mg/day, levofloxacin 400 mg/day, and streptomycin 500 mg/day i.m. Prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day was administered for 2 weeks and tapered down within 4 weeks. The patient was weaned off the ventilator on day 28. Histological examination of the placenta revealed granulomatous inflammation with the presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) on Ziehl-Neelsen staining. Subsequently, the patient's sputum was culture-positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which was susceptible to isoniazid, rifampicin, and streptomycin. A test for HIV antibodies was negative.

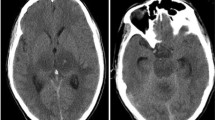

Case 2 was a 35-year-old woman with an uneventful antenatal period who delivered a preterm baby at week 29 of gestation. She had unexplained persistent lymphopenia, with absolute lymphocyte counts of 810/µl and 616/µl at week 6 and week 20 of gestation, respectively. On the day of delivery, she had a transient elevation of the absolute lymphocyte count of 2,040 cells/µl; this gradually returned to the level of 600 cells/µl at week 1 post-delivery. She developed persistent, high fever 2 days after the delivery, but she had no pulmonary symptoms. Laboratory investigations for sepsis and an ultrasound study of the pelvic region were negative. She was given ceftriaxone, gentamicin, and metronidazole empirically. On day 26 her condition deteriorated as she developed mental confusion and left-sided hemiparesis. Emergency contrast computed tomography revealed a noncontrast enhancing hypodense area over the right temporal region, suggestive of cerebral infarction. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed lymphocytic pleocytosis (total cell count of 30×106/l, with 56% lymphocytes) and an elevated protein level. A provisional diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis with endarteritis of the skull base vessels was made.

Therapy was commenced with oral isoniazid 300 mg/day, rifampicin 600 mg/day, and pyrazinamide 2 g/day, along with intravenous amikacin 750 mg/day. Subsequently, the CSF culture was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis sensitive to isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and streptomycin. Antituberculous therapy was administered for 12 months, and the patient recovered with residual left-sided weakness. Re-evaluation of the histological section of the placenta showed a few AFB, compatible with mycobacterial endometritis. The test for HIV antibodies was negative.

A review of the English-language literature revealed a total of 57 episodes of peripartum tuberculosis. Including the present two cases, a total of 29 cases matched our definition (Table 1) [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. The age of the patients ranged from 18 to 36 years, with a median age of 25 years. Two patients had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis and one patient was exposed to tuberculosis during pregnancy [9, 10]. Only two patients were diagnosed with active tuberculosis before delivery, at week 28 and week 34 of gestation, respectively; both cases were meningitis. Another five patients developed nonspecific symptoms and signs suggestive of tuberculosis 2 weeks to 3 months before delivery. The median time to onset of symptoms was 4 days (range, 1–30 days) after delivery, with 75.9% of patients experiencing symptoms within 10 days. Fever occurred in eight patients, three of whom presented with pyrexia of unknown origin for 26, 32, and 37 days, respectively. Localized symptoms, which included headache, neck stiffness, hemiplegia, abdominal pain, respiratory distress, and pleural effusion, were present in 12 patients.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis was cultured from 11 (37.9%) patients, 3 of whom had smear results positive for AFB. Baseline Mantoux tests were performed in three patients and were negative in all three cases. Mantoux tests were performed in seven (24.1%) patients during the period of clinical deterioration and were positive in four. A surge in lymphocyte counts during clinical deterioration was mentioned in one case. Of the 22 patients who were asymptomatic during pregnancy, 21 received antituberculosis therapy, at a median time of 27 days (range, 7–36 days) after the onset of symptoms. The overall recovery rate was 34.5% (10 patients). Residual functional defects such as left-sided hemiparesis and pulmonary insufficiency were present in four (13.8%) patients. Eleven (38%) patients died of peripartum tuberculosis.

Peripartum tuberculosis is a rare but important differential diagnosis of postpartum fever. Early diagnosis is important yet difficult for several reasons. First, few patients have a history of exposure to tuberculosis or a history of the disease itself. Second, the clinical presentation is often nonspecific in the early stage [7, 14]. Fever can be the only presenting symptom, which can make differentiation from endometritis, pelvic thrombophlebitis, and acute pyelonephritis difficult. As a result of the relative immunosuppression that occurs during pregnancy, tuberculin skin tests can be negative in pregnant women with tuberculosis, even in those with recent exposure to tuberculosis [9]. Occasionally, only Gallium scan but not computed tomography was able to detect diffuse peritoneal involvement, and subsequently, laparotomy was required to make the definitive diagnosis of intra-abdominal tuberculosis [14].

In this review the clinical presentation of peripartum tuberculosis was predominantly extrapulmonary tuberculosis, but this might not be representative of the population studied, since publication bias may occur in that patients with more severe clinical situations were more likely to be reported. However clinicians should be aware of the possibility of extrapulmonary tuberculosis if other causes of postpartum fever are excluded.

We speculate that the acute deterioration in patients with peripartum tuberculosis is due to restitution of the patients' immune response after delivery. During pregnancy, there is experimental evidence of progressive suppression of lymphocytic reactivity towards the purified protein derivative of tuberculin, indicating pregnancy-associated depression of cell-mediated immunity [4]. Recently, it was shown that placental products such as progesterone, prostaglandin E2, interleukin-4, and interleukin-10 can impair the T-helper immune response, and polarization to T-helper suppression was also evidenced in peripheral lymphocytes in the maternal circulation [15]. As a result of the immune suppression, tuberculosis occurring in pregnant women is less symptomatic than that in nonpregnant women [16]. After delivery, the lymphocytic proliferative response rapidly returns to normal as early as 24 h, and complete recovery occurs at 4 weeks postpartum [4]. Reversal of T-helper suppression may precipitate either the symptomatic onset of peripartum tuberculosis that may have been present latently or the worsening of symptoms of tuberculosis during pregnancy. Thus, peripartum tuberculosis is a form of immunorestitution disease [17].

The immunorestitution phenomenon of tuberculosis has been reported previously in HIV-positive patients [2], in whom the clinical worsening of pre-existing tuberculosis typically occurred when the CD4+ lymphocyte count recovered following initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Immunorestitution is more likely to occur in HIV-positive patients who experience substantial increases in CD4+ lymphocyte counts [2]. Recently, we have also reported this phenomenon in HIV-negative patients, in whom a surge in lymphocyte counts was observed during paradoxical response [3]. In case 2 of the present study, the acute clinical deterioration immediately after delivery was associated with a rise in lymphocyte counts. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the clinical spectrum of immunorestitution disease in non-HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis and the association between peripartum tuberculosis and a surge in lymphocyte counts.

References

Ormerod P (2001) Tuberculosis in pregnancy and the puerperium. Thorax 56:494–499

Wendel KA, Alwood KS, Gachuhi R, Chaisson RE, Bishai WR, Sterling TR (2001) Paradoxical worsening of tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons. Chest 120:193–197

Cheng VC, Ho PL, Lee RA, Chan KS, Chan KK, Woo PC, Lau SK, Yuen KY (2002) Clinical spectrum of paradoxical deterioration during antituberculosis therapy in non-HIV-infected patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 21:803–809

Covelli HD, Wilson RT (1978) Immunologic and medical considerations in tuberculin-sensitized pregnant patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 132:256–259

Stephanopoulos C (1956) The development of tuberculosus meningitis during pregnancy. Amer Rev Tuberculosis 76:1079–1087

D'Cruz IA, Dandekar AC (1968) Tuberculous meningitis in pregnant and puerperal women. Obstet Gynecol 31:775–778

Maheswaran C, Neuwirth RS (1973) An unusual case of postpartum fever. Acute hematogenous tuberculosis. Obstet Gynecol 41:765–769

Brandstetter RD, Murray HW, Mellow E (1980) Tuberculous meningitis in a puerperal woman. JAMA 244:2440

Myers JP, Perlstein PH, Light IJ, Towbin RB, Dincsoy HP, Dincsoy MY (1981) Tuberculosis in pregnancy with fatal congenital infection. Pediatrics 67:89–94

Good JT Jr, Iseman MD, Davidson PT, Lakshminarayan S, Sahn SA (1981) Tuberculosis in association with pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 140:492–498

Brar HS, Golde SH, Egan JE (1987) Tuberculosis presenting as puerperal fever. Obstet Gynecol 70(3 Pt 2):488–490

Nsofor BI, Trivedi ON (1988) Postpartum paraplegia due to spinal tuberculosis. Trop Doct 18:52–53

Kingdom JC, Kennedy DH (1989) Tuberculous meningitis in pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 96:233–235

Kuppuswami N, Powell L, Freese U (1995) Extrapulmonary tuberculosis as a cause of unexplained postpartum fever. A case report. J Reprod Med 40:232–234

Sacks G, Sargent I, Redman C (1999) Innate immunity in pregnancy. Immunol Today 20:114–118

Carter EJ, Mates S (1994) Tuberculosis during pregnancy. The Rhode Island experience, 1987 to 1991. Chest 106:1466–1470

Cheng VC, Yuen KY, Chan WM, Wong SS, Ma ES, Chan RM (2000) Immunorestitution disease involving the innate and adaptive response. Clin Infect Dis 30:882–892

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, V.C.C., Woo, P.C.Y., Lau, S.K.P. et al. Peripartum Tuberculosis as a Form of Immunorestitution Disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 22, 313–317 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-003-0927-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-003-0927-1