Abstract

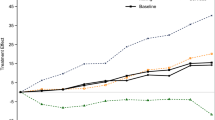

This paper provides evidence for an aspect of trade often disregarded in international trade research: countries’ sectoral export diversification. The results of our semiparametric empirical analysis show that, on average, countries do not specialize; on the contrary, they diversify. Our results are robust for different statistical indices used to measure trade specialization, for the level of sectoral aggregation, and for the level of smoothing in the nonparametric term associated with per capita income. Using a generalized additive model (GAM) with country-specific fixed effects it can be shown that, controlling for countries’ heterogeneity, sectoral export diversification increases with income.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this paper the word diversification, in accordance with most of the empirical literature on the specialization–development relationship, is used just as an antonymous of specialization rather than in association with the concept of risk.

The two sectors previously quoted take the values 15.25 for the Italy’s top sector, and 44.00 for Indonesia's.

This set is generally, but not always, only a limited set of countries (usually a subset of developed countries). Only a small number of papers cover a broad sample of developed and developing countries. See, for example, Imbs and Wacziarg (2003), Koren and Tenreyro (2007), and De Benedictis et al. (2008).

Indeed, if there are evident reasons to use trade data for analysing intra-industry trade and production (employment) data for analysing location patterns, even less consensus seems to characterize the empirical analysis of specialization patterns.

In particular, while the former strand of empirical research has employed a parametric approach (Kim 1995; Amiti 1999; Proudman and Redding 2000; Brasili et al. 2000; Redding 2002; Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2003; Koren and Tenreyro 2007), most recent empirical studies in this area have adopted nonparametric methods (Imbs and Wacziarg 2003; Koren and Tenreyro 2007; and De Benedictis et al. 2008).

Anyway, the nonparametric analysis was applied to both measures of specialization, i.e. relative and absolute indices, finding some relevant differences. More details about such differences are provided in Sect. 4.

As a matter of fact, the more aggregated the data, the less information is likely to be obtained.

Nevertheless, the links between primary and manufacturing sectors are not exclusively limited to algebraic questions (as emphasized by the literature on the Dutch Disease).

Since this study uses trade data, there is no particular reason to assume that the equi-distribution should be considered as the benchmark.

As evidenced in Koren and Tenreyro (2007) such indices are always sensitive to classification; nonetheless, we believe, that our definition of sectors can be useful to look at the time series evidence about countries’ evolving specialization.

As a consequence, OS rg reduces to \( OS^{rg} \; = {{\sum\nolimits_{i\; = \;1}^{n - 1} {\left( {p_{i} } \right)} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sum\nolimits_{i\; = \;1}^{n - 1} {\left( {p_{i} } \right)} } {\sum\nolimits_{i\; = \;1}^{n - 1} {p_{i} } }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\sum\nolimits_{i\; = \;1}^{n - 1} {p_{i} } }}\; = \;1 \) (if the world structure is not perfectly concentrated in the n sector too.).

In the calculation of OS th, when z i /z was equal to 0, lim z→0 z ln(z) = 0.

The nonparametric methodology employed in recent emprical studies (Imbs and Wacziarg 2003; Koren and Tenreyro 2007) is a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing procedure called loess (Cleveland 1979). This procedure allows for determining a smoothed, fitted nonparametric curve to represent the relationship linking sectoral concentration and income. A different nonparametric procedure, the generalized additive model (GAM), is employed in De Benedictis et al. (2008). Such a model allows the empirical researcher to gain more flexibility, as it replaces the linearity assumption with some univariate smooth functions in a nonparametric setting, but retains the additivity assumption.

The most widely used functions are the triangular, gaussian, and tricube functions.

If the data are unevenly distributed or some outliers are present, it could be convenient to use a larger h where the data are sparser and a smaller h when the data are denser.

A full description of how the algorithm works in GAMs is available in Hastie and Tibshirani (1990).

For brevity, nonparametric fitted functions from fixed effects GAM regressions at the 2-digit level of disaggregation are not presented here, given the similarity of the results. On the contrary, the empirical evidence displayed by absolute indices does not provide a uniform pattern of the specialization–income relationship. In particular, in comparison to relative indices, absolute indices tend to display a less pronounced pattern of diversification (the results of nonparametric analysis with absolute indices are available from the authors upon request).

As outlined in Sect. 3, OS me is an inverse index of overall specialization, while OS rg and OS th are direct indices of overall specialization.

In particular the ypc-OS link seems to be nearly linear in the case of OS rg, with all spans.

Albeit always significant, F-tests are usually, but not always, higher when the OS th and the OS rg indices are used, a little bit lower for OS me; they are often higher when a 4-digit sectoral disaggregation is used. The only exceptions to this "rule" are OS me (at 2-digit, first degree polynomial), and, partially, OS th (at 2-digit, first degree polynomial).

Besides, the inclusion or exclusion of agricultural sectors can have its relevance (even if in Imbs and Wacziarg (2003) this seems not to be the case).

New goods sometimes replace old ones, but in other cases they simply add to them.

Manufacturing is defined as the sum of sectors from code 5 to 9. The total number of sectors included in the database is 786.

The choice of total income as a basis for the selection of countries was made to avoid possible distortions due to the presence of too small economies.

Countries in Table 5 are presented in ascending order as to per capita income starting with the lowest income country at the top left of the first column (Bangladesh) and ending with the highest income country at the bottom of the last column (the United States).

References

Amiti, M. (1999). Specialization patterns in Europe. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 135(4), 573–593.

Balassa, B. (1965). Trade liberalization and revealed comparative advantage. Manchester School of Economics and Social Studies, 33(2), 99–123.

Bensidoun, I., Gaulier, G., & Unal-Kesenci, D. (2001). The nature of specialization matters for growth: An empirical investigation. CEPII working paper n. 2001–13. Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales, Paris.

Bowman, A. W., & Azzalini, A. (1997). Applied smoothing techniques for data analysis. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Brasili, A., Epifani, P., & Helg, R. (2000). On the dynamics of trade patterns. De Economist, 148(2), 233–258.

Brülhart, M. (1998). Trading places: Industrial specialization in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 36(3), 319–346.

Brülhart, M. (2001). Evolving geographical specialization of European manufacturing industries. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 137(2), 215–243.

Cleveland, W. S. (1979). Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(368), 829–836.

Cleveland, W. S. (1993). Visualizing data. Summit New Jersey: Hobart Press.

De Benedictis, L., Gallegati, M., & Tamberi, M. (2008). Semiparametric analysis of the specialization–income relationship. Applied Economics Letters, 15(4), 301–306.

De Benedictis, L., & Tamberi, M. (2004). Overall specialization empirics: Techniques and application. Open Economies Review, 15(4), 323–346.

ECLAC-UN (Economic Commission for Latin America, the Caribbean–United Nations) (2003). Competitiveness Analysis of Nations (CAN2003). Santiago de Chile: ECLAC-UN. CD-ROM.

Fox, J. (2000a). Nonparametric simple regression: Smoothing scatterplots. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fox, J. (2000b). Multiple and generalized nonparametric regression. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (1986). Generalized additive models. Statistical Science, 1(3), 297–318.

Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (1990). Generalized additive models. London: Chapman and Hall.

Hausmann, R., Hwang, J., & Rodrik, D. (2005). What you export matters. NBER working paper 11905. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Imbs, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Stages of diversification. American Economic Review, 93(1), 63–86.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sørensen, B., & Yosha, O. (2003). Risk sharing and industrial specialization: Regional and international evidence. American Economic Review, 93(3), 903–918.

Kim, S. (1995). Expansion of markets and the geographic distribution of economic activities: The trends in U.S. regional manufacturing structure, 1860–1987. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(4), 881–908.

Koren, M., & Tenreyro, S. (2007). Volatility and development. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(1), 243–287.

Krugman, P. (1987). The narrow moving band, the Dutch disease, and the competitive consequences of Mrs. Thatcher: Notes on the presence of dynamic scale economies. Journal of Development Economics, 27(1–2), 41–55.

Peretto, P. F. (2003). Endogenous market structure and the growth and welfare effects of economic integration. Journal of International Economics, 60(1), 177–201.

Proudman, J., & Redding, S. (2000). Evolving patterns of international trade. Review of International Economics, 8(3), 373–396.

Redding, S. (2002). Specialization dynamics. Journal of International Economics, 58(2), 299–334.

Stockey, N. (1988). Learning by doing and the introduction of new goods. Journal of Political Economy, 96(4), 701–717.

Theil, H. (1967). Economics and information theory. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Weinhold, D., & Rauch, J. E. (1999). Trade, specialization, and productivity growth. Canadian Journal of Economics, 32(4), 1009–1027.

World Bank. (2005). Global development network growth database. Washington, DC: World Bank. CD-ROM.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Antonio Ciccone, Lucia Tajoli and Michele Fratianni for comments and suggestions, and to CNR for financial support. We are also grateful to an anonymous referee for his/her helpful comments. All remaining errors and omissions are our own responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Our data set is based on trade data and consists of a balanced panel stemming from two different sources: exports come from CAN2003 (ECLAC-UN 2003), and per capita income from the World Development Indicators (World Bank 2005). Specifically, our data set consists of:

-

export data based on the SITC rev.2 classification at the 2- and 4-digit level (about 30 and 500 manufacturing sectors, respectively);Footnote 27

-

annual observations over the 1985–2001 period;

-

39 countries selected on the basis of total GNP (>100 billions as in WB WDR data set);Footnote 28

-

per capita income (ypc) is measured in PPP constant 2,000 international dollars.

The 39 countries included in the sample, ordered according to average per capita income,Footnote 29 are listed in Table 5, while Table 6 presents the summary statistics of the variables used in nonparametric analysis for the whole period, the first and last year of the sample, respectively.

About this article

Cite this article

De Benedictis, L., Gallegati, M. & Tamberi, M. Overall trade specialization and economic development: countries diversify. Rev World Econ 145, 37–55 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0007-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-009-0007-4