Abstract

We evaluate planetary boundary-layer (PBL) parametrizations in the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) numerical model, with three connected objectives: first, for a 16-year period, we use a cluster analysis algorithm of three-day back-trajectories to determine general synoptic flow patterns over Barcelona, Spain arriving at heights of 0.5, 1.5, and 3 km; to represent the lower PBL, upper PBL, and lower free troposphere, respectively. Seven clusters are determined at each arriving altitude. Regional recirculations account for 54 % of the annual total at 0.5 km, especially in summertime. In the second objective, we assess a time-adaptive approach using an extended Kalman filter to estimate PBL height from backscatter lidar returns at 1200 UTC \(\pm \) 30 min for 45 individual days during a seven-year period. PBL heights retrieved with this technique are compared with three classic methods used in the literature to estimate PBL height from lidar. The methods are validated against PBL heights calculated from daytime radiosoundings. Lidar and radiosonde estimated PBL heights are classified under objectively-determined synoptic clusters. With the final objective, WRF model-simulated PBL heights are validated against lidar estimates using eight unique PBL schemes as inputs. Evaluation of WRF model-simulated PBL heights are performed under different synoptic situations. Determination coefficients with lidar estimates indicate the non-local assymetric convective model scheme is the most reliable, with the widely-tested local Mellor–Yamada–Janjic scheme showing the weakest correlations with lidar retrievals. Overall, there is a systematic underestimation of PBL height simulated in the WRF model.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The planetary boundary-layer (PBL) height is often calculated as the altitude of the inversion level separating the free troposphere from the boundary layer (Stull 1988). Turbulent fluxes within the PBL occur at temporal and spatial scales that are much smaller than the grid sizes and temporal resolution of today’s advanced mesoscale meteorological models. PBL parametrization schemes are employed in atmospheric models to handle the vertical diffusion in the whole column of the boundary layer (Skamarock et al. 2008), while surface-layer and land-surface schemes provide the surface fluxes needed for PBL schemes to determine the flux profiles within the well-mixed boundary layer and the stable layer using the surfaces fluxes as inputs, thus providing atmospheric tendencies of temperature, moisture, and horizontal momentum in the entire atmospheric column.

Air quality forecast systems require timely, reliable, and accurate meteorological representations of boundary-layer properties. PBL height is an important input in an air quality forecast system (Seaman 2000), as it delineates the top of the atmospheric mixing layer. Numerous operational definitions exist for determining PBL height from both observations and model simulations. Lidars with high spatial (\(<\)30 m) and temporal resolutions (\(<\)1 min) can be employed to monitor the PBL height using the backscattered light from aerosols as tracers.

Lidar presents advantages over the more traditional use of radiosondes to retrieve PBL height, advantages that include lidar high temporal frequency and vertical spatial coverage, possible continuous operation and in a nearly automated way. Thus, a continuously-recorded PBL height allows for more in-depth analysis such as diurnal evolution and long-term climate studies. Typically, radiosondes are launched only twice each day, with limited vertical resolution and potential tracking problems in the lower boundary layer.

Several methods have been applied previously to determine the PBL height from lidar observations; here we refer to these past methods as classic methods. They comprise both objective and subjective methods: objective methods consist of various forms of derivative methods (Flamant et al. 1997; Sicard et al. 2006, 2011), wavelet analysis methods (Baars et al. 2008; Gan et al. 2011), the threshold method (Melfi et al. 1985; Boers and Eloranta 2006), and the variance method (Menut et al. 1999; Hennemuth and Lammert 2006). Visual inspection methods (Quan et al. 2013) are infrequently used as a subjective approach, which adds levels of ambiguity that may possibly lead to poor results. Finally, an objective approach using an adaptive extended Kalman filter has recently been developed and tested (Lange et al. 2013).

These methods have been inter-compared previously (Seibert et al. 2000; Pal et al. 2010). Based upon the outcomes of these previous studies an optimum method has never been determined for estimating PBL height in all atmospheric conditions, especially complex lidar scenes with multiple aerosol layers. The choice of the operational definition of PBL height can have a large impact on the results, especially for the validation of model simulations.

A large number of previous studies have been carried out to validate PBL parametrization schemes in mesoscale meteorological models using observations (e.g., lidar, surface, upper air) and to evaluate the sensitivity of atmospheric parameters (i.e., PBL height, temperature) to the schemes. In areas surrounding the Mediterranean region the two primary meteorological models used in earlier efforts were the fifth generation Penn State-NCAR mesoscale model (MM5) model (Pérez et al. 2006; Bossioli et al. 2009) and the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model (Borge et al. 2008; Pichelli et al. 2014). Overall, it has been determined that no PBL scheme is superior to the others under all conditions, and each scheme has strengths and weaknesses. However, these previous efforts have shown that non-local PBL schemes usually provide lower biases and errors in certain cases, mainly in situations dominated by strong convection and little or no shear (Pérez et al. 2006).

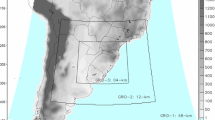

The region of interest in the present study is the urban metropolis of Barcelona, Spain, which is a complex geographical area located in the north-east Iberian Peninsula. The regional climate is affected by synoptic and mesoscale meteorological processes (Baldasano et al. 1994; Gonçalves et al. 2009), with some mesoscale processes in this region the result of the orientation of topographic features (pre-coastal and coastal mountain ranges) relative to the Mediterranean Sea (Fig. 1c). Previous work has found that both synoptic circulations and mesoscale processes combine to influence the height of the PBL (Sicard et al. 2006), which in the north-east Iberian Peninsula is highly variable and dependent on the general synoptic flow.

Model domain configuration (a) with the European-level parent domain (d01, 12 km \(\times \) 12 km resolution), Iberian Peninsula domain (d02, 4 km \(\times \) 4 km resolution), and the Barcelona geographical area domain (d03, 1 km \(\times \) 1km resolution). The Iberian Peninsula and Barcelona domains with associated topography are shown in (b). The topographic map is further zoomed in to the Barcelona domain (c), with a bold red star denoting the location of the lidar site

There are three main objectives of our study: the first is to provide an updated clustering of general synoptic flow patterns that affect the north-eastern Iberian Peninsula. This is accomplished utilizing a long period of kinematic back-trajectories and a cluster analysis algorithm. Secondly, results of the cluster analysis are used as complementary information to evaluate an adaptive technique using an extended Kalman filter (EKF) to estimate PBL height from lidar observations. The technique is compared with classic methods under different objectively determined atmospheric situations produced with the cluster analysis. Lidar data are selected around the time of daily daytime radiosonde launches to ensure a significantly comparative analysis. The final objective is to evaluate PBL height simulated by the WRF model using different PBL parametrization schemes. Model-simulated PBL heights are validated against those estimated with lidar using the extended Kalman filter method.

Section 2 describes the set-up of the WRF model, the instrumentation used for PBL height estimates, and the cluster analysis algorithm, while Sect. 3 summarizes classic methods for estimating PBL height from lidar and presents descriptive information on the extended Kalman filter technique. In Sect. 4 we present the results of the cluster analysis, the comparisons between lidar methods and radiosoundings, and the performance evaluation of the WRF model PBL schemes. Finally, conclusions are drawn and future work is discussed in Sect. 5.

2 Model Configuration, Observations, and Cluster Analysis

2.1 WRF Model Set-Up

Here we use WRF model version 3.4.1 in diagnostic mode with the Advanced Research WRF (ARW) dynamical core. Three model domains (Fig. 1) were configured with varying horizontal grid spacing at the parent European level (12 km \(\times \) 12 km), and two one-way nested domains for the Iberian Peninsula (4 km \(\times \) 4 km) and Catalonia (1 km \(\times \) 1 km) regions. It is assumed that 1 km \(\times \) 1 km spatial resolution is of fine enough detail to resolve most mesoscale features in the complex study area.

Initial and boundary conditions were obtained from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Final Analysis product, with operational global analysis data on \(1^{\circ } \times 1^{\circ }\) grids available at six-hourly timesteps. The final analyses are available for the surface and 26 mandatory levels from 1000 to 10 hPa.

Daily WRF model simulations were computed with a 36-h forecast cycle, including the recommended minimum of 12 h allotted for model spin-up. Each simulation was initialized from 1200 UTC of the previous day, with a spin-up cycle added to counter instability issues with the simulation. The PBL height is evaluated at each time step after 24 h of runtime. An output temporal resolution of 1 hour was chosen, and the model was run with 38 terrain-following vertical levels, with the top at 50 hPa.

The physics options selected include WRF single-moment 3-class microphysics (Hong et al. 2004), Kain–Fritsch cumulus parametrization (Kain 2004), Dudhia shortwave radiation (Dudhia 1989), rapid radiative transfer model longwave radiation (Mlawer et al. 1997), and the Noah land-surface model (Tewari et al. 2004)—see Skamarock and Klemp (2008) for details.

One of our primary objectives is to provide a performance evaluation of PBL height simulated by different PBL parametrizations. In version 3.4.1 of the WRF-ARW model there is the option to choose from nine PBL schemes. Each PBL scheme is associated with one or more surface-layer schemes. So a summary of the eight PBL schemes and selected surface-layer schemes used herein is shown in Table 1.

The PBL parametrizations selected consist of five local and three non-local closure schemes. The operational definition of PBL height in the individual schemes falls into one of two general classes: the first class calculates the PBL height as the lowest level at which the bulk Richardson number \((Ri_\mathrm{b})\) exceeds a certain threshold. This lowest level needs to be located above a certain pre-determined minimum height. The second class determines the PBL height at a level where the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) profile decreases to some pre-defined threshold value. A brief description of the schemes follow.

The first and most widely-used PBL scheme is the Yonsei University (YSU) scheme (Hong et al. 2006), which is a first-order, non-local scheme with an explicit entrainment layer and a parabolic K-profile in an unstable mixed layer. It is a modified version of the medium-range forecast scheme (Hong and Pan 1996) from the legacy MM5 model (Dudhia 1993). The largest improvement to the YSU scheme was the addition of an explicit term for the treatment of the entrainment zone. PBL height in the YSU scheme is determined from the \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) method, with a threshold value of zero.

The next most widely used PBL scheme is the Mellor–Yamada–Janjic (MYJ) scheme (Janjic 2002), which is a 1.5-order prognostic TKE scheme with local vertical mixing, and a modified version of the old Eta scheme from the MM5 model (Janjic 1990). PBL height is determined from the TKE, where the PBL top is defined as the level at which the profile decreases to a prescribed small value, here taken as 0.2 m\(^{2}\) s\(^{-2}\). This scheme is appropriate for all stable and slightly unstable flows; however, it is not recognized as appropriate for simulating convective processes.

The third scheme is the Quasi-Normal Scale Elimination (QNSE) scheme (Sukoriansky et al. 2005), which is a 1.5-order, local closure scheme and has a TKE prediction option for stably stratified regions. Here, the PBL height is defined as the height at which the TKE decreases to a prescribed low value, as in the MYJ scheme. In WRF model v3.4 the value is 0.01 m\(^{2}\) s\(^{-2}\). The scheme is valid for stable stratification and weakly unstable conditions, but needs improvement in truly unstable cases.

The fourth scheme is the Mellor–Yamada–Nakanishi–Niino level-2.5 (MYNN2) scheme (Nakanishi and Niino 2006) (the Mellor–Yamada–Nakanishi–Niino level-3 (MYNN3) scheme will not be evaluated), which is a 1.5-order, local closure scheme tuned to a database of large-eddy simulations in order to overcome the typical biases associated with other MY-type schemes, such as insufficient growth of the convective boundary layer and underestimation of TKE. The MYNN2 scheme predicts subgrid TKE terms. PBL height is determined as the height at which the TKE falls below a critical value of \(1.0 \times 10^{-6}\) m\(^{2}\) s\(^{-2}\) in this version of the WRF model.

The fifth scheme is the Asymmetrical Convective Model version 2 (ACM2) scheme (Pleim 2007), which is a first-order, non-local closure scheme and features non-local upward mixing and local downward mixing. It is a modified version of the ACM1 scheme from the MM5 model, which was a derivative of the Blackadar scheme (Blackadar 1978). The scheme has an eddy-diffusion component in addition to the explicit non-local transport of the ACM1 scheme. The PBL height is determined as the height at which the \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) calculated above the level of neutral buoyancy exceeds a critical value \((Ri_\mathrm{bc} = 0.25)\). For stable or neutral flows the scheme shuts off non-local transport and uses local closure.

The sixth scheme is the Bougeault–Lacarrere (BouLac) scheme (Bougeault and Lacarrere 1989), which is a 1.5-order, local closure scheme and has a TKE prediction option designed for use with the Building Environment Parametrization multi-layer, urban canopy model (Martilli et al. 2002). The BouLac scheme diagnoses PBL height as the level at which the prognostic TKE reaches a sufficiently small value (in version 3.4 of the WRF model it is \(0.005\,\hbox {m}^{2}\,\hbox {s}^{-2})\).

The seventh scheme is the University of Washington (UW) scheme (Bretherton and Park 2009), which is a 1.5-order, local TKE closure scheme from the Community Earth System Model (Gent et al. 2011). The PBL height is defined as the inversion height between grid levels via a \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) threshold, with a critical value of 0.25 used in all cases of stability, as in the ACM2 scheme.

Finally, the eighth scheme is the total energy-mass flux (TEMF) scheme (Angevine et al. 2010), which is a 1.5-order, non-local closure scheme and has a subgrid-scale total energy prognostic variable, in addition to mass-flux type shallow convection. The TEMF scheme uses eddy diffusivity and mass flux concepts to determine vertical mixing, with the PBL height calculated through a \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) method with a threshold value of zero. In this study we encountered minor stability issues with seven simulation days using the TEMF scheme. The stability issues are due to a threshold exceedance of potential temperature over the desert regions in our parent domain. Decreasing the time between calls to the radiation physics scheme improved the stability for five of the seven simulation days.

2.2 Elastic Backscatter Lidar

Data from two multiwavelength elastic Raman lidars (Rocadenbosch et al. 2002) were obtained from the database of the Remote Sensing Laboratory in the Department of Signal Theory and Communications at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) in Barcelona, Spain. The lidar group at the UPC is a member station of the European Aerosol Research Lidar Network (EARLINET; Bosenberg et al. 2001). Lidar observations were selected around 1200 UTC \(\pm \) 30 min from a database covering a 7-year period between 2007 and 2013. This criterion led to a total of 45 individual measurement days. Individual daily WRF model simulations were run for the same 45 days for the evaluation of PBL parametrization schemes.

The history of the lidar program at UPC dates back to the first Spanish elastic backscatter lidar in 1993. From 2007 to August 2010 was a 3-channel instrument comprised of elastic and Raman channels, and since September 2010, is a 6-channel multi-spectral instrument with elastic and Raman channels, and aerosol/water-vapour capabilities. Characteristics of the two instruments are shown in Table 2.

Raw lidar data for this analysis are obtained from the visible channel (532-nm elastic, analog acquisition) with either 15-m (2007), 7.5-m (2008–August 2010), or 3.75-m (after August 2010) raw vertical resolution and 1-min averaged temporal resolution. The 532-nm analog channel was selected considering its acceptable signal-to-noise ratio \(>\) 5 at the maximum study range (3 km) and the contrast between aerosol and molecular backscatter returns. Pre-processing of the lidar returns includes removal of the molecular background using a Rayleigh fit to achieve range-corrected signal.

Lidar range-corrected signal are used as input to the PBL-retrieval algorithms explained in Sect. 3. Range is limited at low levels due to the incomplete overlap between the laser transmitter and the receiving telescope (Collis and Russell 1976). For boundary- layer studies overlap issues may make PBL height estimations unreliable or unavailable. The instruments described herein have an approximate overlap range as high as 0.45 km, below which the lidar returns may be unreliable for the analysis. This is taken into account when retrieving the PBL height with the various estimation methods.

2.3 Radiosoundings

It is important to have a reference PBL height to compare to the estimates from lidar observations. PBL height calculated from radiosounding measurements have become an accepted reference in the community (Seibert et al. 2000) and are exploited in this evaluation. Upper-air meteorological measurements are obtained from 1200 UTC radiosonde launches performed by the Meteorological Service of Catalunya in Barcelona (41.38 N, 2.12 E, 0.98 km a.s.l.). The meteorological service routinely launches the radiosondes approximately 0.72 km distance from the site of the UPC lidar. This radiosonde instrument records atmospheric variables of temperature (\(^\circ \)C), relative humidity (%), wind speed (m s\(^{-1}\)) and direction (\(^\circ \)), and barometric pressure (hPa).

PBL height is calculated here from the radiosounding data using the \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) method (Holtslag et al. 1990), the same method used in many of the WRF model PBL schemes (Sect. 2.1) to diagnose the PBL height. The \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) approach requires wind speed and direction, barometric pressure, and temperature as input variables at each altitude. The \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) method is a proxy of where the atmospheric state transitions from turbulent to laminar, possibly indicating the top of the PBL. PBL height is calculated at the altitude where \(Ri_\mathrm{b}\) exceeds a critical Richardson number \((Ri_\mathrm{bc})\).

From many previous studies the \(Ri_\mathrm{bc}\) is selected as a universal constant between 0.1 and 1.0 (Richardson et al. 2013). Typically higher critical values are selected in areas where the turbulent transition from an atmosphere dominated by buoyant forces to shear is larger. We tested a range of critical values against visual inpection of vertical profiles of potential temperature and humidity, and found that \(Ri_\mathrm{bc} = 0.55\) is the most appropriate value for this dataset. This critical value is higher than used in previous studies (Sicard et al. 2006) but is still considered as an acceptable transition value between the buoyancy and shear states for a complex urban area.

2.4 Back-Trajectory Cluster Analysis

The aerosol load in the boundary layer can be developed and modified depending on the predominant synoptic flow. Changes in the aerosol load, especially in the boundary layer to lower free troposphere, can affect the PBL height estimation from lidar.

To enhance the robustness of the analysis, the methods to obtain PBL height from lidar are evaluated under different synoptic flows determined with an objective procedure. In order to objectively quantify the atmospheric dynamics from a synoptic perspective and select representative lidar cases from varying atmospheric flows, a cluster analysis technique is performed.

A semi-automated cluster analysis technique based on the methodology of a previous study (Jorba et al. 2004) is used, due to its relatively small computational requirements. The main component necessary for the analysis is that involving backward trajectories (back-trajectories). Three-day back-trajectories are calculated using the Hybrid Single Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model (Draxler and Rolph 2013) with endpoint of the Barcelona lidar site at three vertical levels: 0.5, 1.5, and 3 km. These levels are selected as altitudes representing a level within the boundary layer, near the top of the PBL, and within the low free troposphere, respectively. The back-trajectories are calculated once per day ending at 1200 UTC. Input data are downloaded from the NCEP Global Data Assimilation System composed of a 16-year period from 1998 to 2013, and interpolated onto a \(1^\circ \times 1^\circ \) grid with a 6-h temporal resolution.

Jorba et al. (2004) employed the cluster analysis algorithm over Barcelona using 5 years (1997–2002) of four-day back-trajectories. We selected three-day back-trajectories because we are interested in shorter-range local effects. The algorithm functions by determining an optimal number of cluster groups based on synthetic seed trajectories of varying lengths and curvature, where the optimal number of clusters is obtained through a multivariate statistical method. A compromise is reached between the total number of clusters retained without losing information. For this study we selected seven clusters at each arriving altitude.

3 Methods to Estimate PBL Height from Lidar

3.1 Classic Methods

Classic methods used in this study are classified as gradient-based, variance-based, or subjectively-based. In the following we describe general characteristics of the methods and highlight previous works evaluating these techniques.

Wavelet-based methods can be used to objectively determine PBL height from lidar observations, in particular, the wavelet covariance transform (WCT) with a Haar wavelet. The general approach is to employ the Haar wavelet function to extract scale-dependent information from the original lidar range-corrected signal profile; this detects step changes in the range-corrected signal. The WCT method has been used in many previous studies (Baars et al. 2008; Gan et al. 2011) and has proven to be a computationally robust technique.

With the WCT method, the maximum value of the covariance transform corresponds to the strong step-like decrease in the lidar range-corrected signal, where the gradient in aerosol concentration is the most clearly defined. The corresponding height of the resulting maximum is identified as the PBL height. Pal and Devara (2012) discovered that key uncertainties in the determination of PBL height by this technique lie in the choice of the upper and lower range limits of integration for calculating the wavelet transform and proper choice of the dilation parameter. To recall, the dilation parameter is the vertical extent of the step function. Baars et al. (2008) introduced a modified version of the WCT method in an attempt to find an appropriate dilation dependent on the atmospheric situation. For this study, a series of dilation values have been tested with the Barcelona lidar data. For simplification of applying the WCT method we use a constant dilation (20\({\Delta }{R})\) for the entire lidar dataset. In this application \({\Delta }R\) is the range resolutions of the two instruments described in Table 2.

Recently, it has been shown (Comerón et al. 2013) that the WCT method using a Haar wavelet is completely equivalent to derivative-based methods when applied to spatially low-pass filtered range-corrected signals. Therefore, we here use the WCT method as described above, and that has the advantage of performing the PBL height estimate in a single, computationally efficient step.

Another classic method used in this study is the threshold method (Melfi et al. 1985; Boers and Eloranta 2006). This simple technique functions using a user-defined critical threshold value in the lidar range-corrected signal to distinguish the PBL from the free troposphere. Threshold values vary for the two instruments used here, with their ranges shown in Table 2. Typically, the method also requires the user to select an upper and lower search altitude, and for our purposes we constrain to a lowest altitude of 0.45 km that corresponds to the overlap range of the UPC lidar. The highest altitude is chosen as 4 km as a realistic estimate of the possible highest PBL height in Barcelona.

Finally, the variance method (Menut et al. 1999; Hennemuth and Lammert 2006) makes use of the vertical profile of the variance of the lidar range-corrected signal. With this method the PBL height is the level at which there is a clear maximum in the variance profile. We subject 15 profiles of 1-min temporal resolution to the variance algorithm to estimate the PBL height.

3.2 UPC Extended Kalman Filter Technique

An adaptive approach utilizing an extended Kalman filter (Brown and Hwang 1982) has been developed and tested in the UPC Remote Sensing Laboratory to trace the evolution of the PBL (Lange et al. 2013). The technique builds upon previous work (Rocadenbosch et al. 1998, 1999). Lange et al. (2013) found that the main advantages of the extended Kalman filter are the ability to time-track the PBL height without need for long time averaging and range smoothing and the ability to perform well under low signal-to-noise ratio. The extended Kalman filter technique benefits from the knowledge of past PBL height estimates and statistical covariance information to predict present-time estimates.

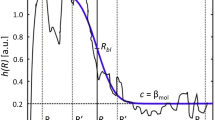

The extended Kalman filter approach is based on estimating four time-adaptive coefficients of a highly simplified erf-like curve model, representing the PBL transition in terms of the lidar range-corrected signal. The erf-like model, h(R), is formulated as follows

where R is the range, \(R_\mathrm{bl}\) is an initial guess of the PBL height, a is the entrainment zone scaling factor, A is the amplitude of the erf transition, and c is the average molecular background at the bottom of the free troposphere. It is important in the extended Kalman filter technique to initialize the state vector parameters \((R_\mathrm{bl},a,A,c)\) properly. Ranges of the initial state vector parameters for the two instruments are shown in Table 2. If the state vector is not initialized correctly one can expect unreliable estimates of PBL height.

For illustrative purposes an annotated 1-min lidar backscatter profile is shown in Fig. 2, where the initial state vector parameters have been selected to evaluate a PBL height around 1.4 km, previously known from radiosounding data. In this case a narrow transition amplitude (A) was chosen since there are at least two other transition zones below 1.75 km. If we had selected a broader transition amplitude most likely the filter would have taken longer to converge on a solution.

1-min lidar power \(\times \) range-squared \((\hbox {PR}^2)\) profile (arbitrary units) at 532 nm wavelength (solid black line) from 17 June 2013 at 1209 UTC. Annotated are the extended Kalman filter characteristic parameters \((R_\mathrm{bl}, a, A\), and c). \(R_{1}\) and \(R_{2}\) are the start and end range limits defining the length of the observation vector passed to the filter; \(R_{1}^\prime \) and \(R_{2}^\prime \) are the start and end range limits of the erf-like PBL transition zone

Extended Kalman filter state vector initialization also requires statistical covariance information from the user side, accomplished using atmospheric state-noise and error covariance matrices. The statistical covariance information, along with the state vector and Kalman gain, are updated recursively at each 1-min iteration of the filter. With use of this recursive procedure, the extended Kalman filter adjusts the projection trajectory of the PBL atmospheric variables, and improves estimation of the PBL parameters via a new atmospheric state vector.

It is important to note range-corrected signal input to all lidar-based estimation methods have not been further range-smoothed or time-averaged, as one objective is to display the advantages of the extended Kalman filter technique under these criteria. PBL heights are estimated for all lidar methods using the clean 1-min temporal resolution. An average of five 1-min PBL height estimates closest to 1200 UTC is evaluated for each case, allowing for a more representative comparison to radiosoundings as the PBL height can fluctuate drastically over short time periods. PBL height estimates are shown in km a.s.l. throughout.

A common statistical technique called the coefficient of determination \((R^{2})\) is used to measure the correspondence between the lidar-estimated and radiosonde-calculated PBL heights; the same statistic is used for the performance evaluation of the WRF simulations. \(R^{2}\) (Upton and Cook 2008) can be used to explain the goodness of fit between the dependent and independent variables. Values of \(R^{2}\) range from 0 – 1 with higher values indicating a closer correspondence between the variables.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 Objectively Determined Synoptic Cluster Types

From the cluster analysis, seven individual synoptic clusters are determined at each arriving altitude (0.5, 1.5, and 3 km). Overall, cluster types at the three arriving altitudes show similar patterns (Fig. 3). However, key differences are found when assessing the results of the cluster analysis at the different levels and when comparing with previous results found in Jorba et al. (2004) at the 1.5 and 3 km arriving altitudes.

Centroids (white diamonds) and frequency (% total) of the seven clusters arriving at 3 km (a), 1.5 km (b), and 0.5 km (c) altitudes. Clusters at 3 km: north (powder blue), east (cyan), south-west (orange), west (red), fast west (orange-red), north-west (blue), and slow south-west (yellow). Clusters at 1.5 km: north (powder blue), north-east (cyan), south-west (orange), west (red), fast west-north-west (blue), recirculations from the west (yellow), and recirculations from the east (light green). Clusters at 0.5 km: north (powder blue), north-east (cyan), south-west (orange), west (red), north-west (blue), recirculations from the west (yellow), and recirculations from the east (light green). Finally (d), monthly frequency (annual %) of occurrence of each cluster arriving at 1.5 km with the same colour scheme

Seven individual synoptic clusters arriving at 1.5 km and their associated centroids are shown in Fig. 3b. The general synoptic flow at this altitude is a proxy for flow near the top of the PBL in the Barcelona area. The monthly temporal frequency of the different clusters is shown in Fig. 3d, expressed in terms of an annual percentage; the monthly temporal frequencies for clusters at 0.5 and 3 km altitudes are similar to that at 1.5 km, but not presented here.

Regional recirculations from the east or west are the most predominant synoptic clusters throughout the year, accounting for 44.5 % of the total (5756) back-trajectories. Regional recirculations occur most often in the summertime when the synoptic situation is stagnant, thus leading to strong mesoscale processes at low levels of the atmosphere (Baldasano et al. 1994). For simplicity, hereafter we define the term regional recirculations as a combination of the easterly and westerly clusters.

The frequency of lidar days in a particular cluster at 1.5 km shows that 56 % of the lidar data falls into the regional recirculation categories. The next most frequent cluster is synoptic flow from the north (20 %), followed by flow from the south-west (15.6 %). The other three synoptic clusters; flows from the north-east, west, and fast west-north-west, in total account for \(<\)10 % of the available lidar days.

Synoptic flow at 0.5 km is important since this height is an altitude typically within a well-defined PBL. Centroids of the seven individual synoptic clusters arriving at 0.5 km are shown in Fig. 3c. As with clusters at 1.5 km, regional recirculations are the most predominant synoptic pattern. The predominance of regional recirculations at both altitudes is attributable to the complex diurnal mesoscale processes that result from the location of Barcelona between the mountains and the Mediterranean Sea.

The frequency of lidar days in synoptic clusters arriving at 0.5 km altitude is similar to that at 1.5 km, except regional recirculations show an even greater dominance (73 %) of the available lidar days. This is mainly due to the topographic features of the area acting as a barrier to the other synoptic flows, and confirmed by the lack of lidar days with flows from the south-west and north-west, with only 4 % of the total.

Finally, the centroids of seven distinct synoptic clusters arriving at 3 km are shown in Fig. 3a, an altitude representative of the lower free troposphere. The main difference between cluster types at this altitude and the two lower levels is the substitution of regional recirculations for slow south-westerly and easterly synoptic flows. This is most likely due to the lack of the topographic barriers found at the lower altitudes. This finding is a departure from Jorba et al. (2004) where they found regional recirculations at both 3 and 1.5 km altitudes.

The frequency of lidar days in clusters arriving at 3 km show some differences from those at 1.5 and 0.5 km. Weak south-west and north-west synoptic flows are the most predominant, accounting for 24 and 22 % of the total, respectively. If we combine weak south-west and south-west flows into one group, they account for 42 % of the lidar days. Synoptic flows from the south-west are a major contributor to desert dust outbreaks in the north-east Iberian Peninsula.

It is evident from Fig. 3 that the overall patterns (curvature) of the synoptic clusters are similar at all arriving altitudes selected for this study. The primary difference between results at different altitudes is the length (magnitude) of the centroids. It can be seen from Fig. 3 that the length of the centroid increases with an increase in the arriving altitude, indicative of greater wind speeds. We present statistical comparisons between lidar-estimated and radiosonde-calculated PBL heights according to synoptic clusters.

4.2 PBL Height Comparisons Between Lidar Methods and Radiosounding

The comparison of PBL height estimates between the different lidar methods and radiosoundings is divided into two focus areas: first, we discuss comparisons for the total collection of lidar observations (2007–2013), and then comparisons are made with respect to the synoptic flows objectively determined with the cluster analysis.

Over the 2007–2013 data collection period the 45 individual measurement days yield an average PBL height of 1.28 \(\pm \) 0.4 km (1 \(\sigma \) based on a normal distribution) at 1200 UTC via the extended Kalman filter method. As mentioned previously, 1200 UTC was selected as the observation time for two main reasons. The first reason is that 1200 UTC is very close to the time of maximum solar insolation at Barcelona, which typically leads to the daytime maximum PBL height. The second reason is to compare with radiosonde launches, which we use as the reference PBL height.

The average PBL height estimated with the extended Kalman filter technique is very close to the 1.27 km average height determined with the threshold method, but farther apart when compared with estimates from the WCT (1.23 km) and variance (1.16 km) methods. However, the standard deviations from each of the methods are quite similar. The average PBL height estimated with the extended kalman filter method is very similar to results found by Sicard et al. (2006, 2011) in studies over Barcelona. Sicard et al. (2011) estimated an annual average PBL height of 1.21 km using the gradient method. It is well-known from previous studies that the PBL height in the north-east Iberian Peninsula does not vary much with time of the year. Sicard et al. (2006) estimated an average PBL height of 1.45 km in summer and 1.42 km in winter using 162 days of lidar data.

Due to a lack of observations in some synoptic clusters, the determination coefficients can only be calculated for the total collection of observations. If the whole collection of PBL height estimates is considered, including outliers, the determination coefficient between PBL heights estimated with the extended kalman filter technique and radiosoundings is relatively very high (\(R^{2} = 0.77\), \(N = 45)\). The threshold method shows the next best correspondence \((R^{2} =0.19)\), though much weaker with the other two classic methods \((R^{2} = 0.02\) for the WCT method and \(R^{2} \approx 0\) for the variance method), most likely due to the lack of range smoothing and temporal averaging of the range-corrected signal for which these methods perform best, especially for complex scenes.

To further improve the results, lidar-based estimates with gross outliers are removed prior to evaluating the correlation statistics. Gross outliers are defined as biased estimates (lidar PBL height \(-\) radiosounding PBL height) within \(\pm \)1 \(\sigma \) of the mean PBL height of the associated histogram for each method (Fig. 4), which corresponds approximately to a 25 % underestimate or overestimate from the lidar-retrieved PBL height. Here we apply a Gaussian distribution fit. The classic methods greatly improve under these conditions, with the threshold method (\(R^{2} = 0.73\), \(N = 36\)), variance method (\(R^{2}= 0.37\), \(N = 34\)), and WCT method (\(R^{2} = 0.41\), \(N = 34\)). However, the extended Kalman filter method also improves (\(R^{2} = 0.96\), \(N = 34\)) with a strong correspondence to the lidar estimates.

Investigation of individual cases with gross underestimates and overestimates reveal an association to certain synoptic flow clusters. More than 80 % of the identified outliers are associated with regional recirculations and synoptic flows from the south-west. It is well-known that regional recirculations and south-west flows are complex atmospheric situations, typically with additional aerosol layers in or just above the PBL. Scatter diagrams between lidar methods and radiosoundings for each cluster type arriving at 1.5 km altitude are shown in Fig. 5. It is clearly seen that the extended Kalman filter method is superior under all synoptic flows, followed by the threshold method. The largest deviations from the 1:1 line occur with south-west synoptic flows and regional recirculations. Scatter plots for clusters arriving at 0.5 and 3 km altitudes show similar patterns to 1.5 km, so they are not shown.

Scatter plots between PBL heights from lidar-based methods and radiosounding for a extended Kalman filter, b threshold, c wavelet covariance transform, and d variance methods. \(1\,\sigma \) outliers have been removed. Lidar observations have been colour-coded according to their cluster type arriving at 1.5-km altitude. The 1:1 line (solid red) has been added. Units of km

The lidar data are grouped into the seven synoptic clusters arriving at 1.5 km altitude. The highest PBL height estimated by the extended kalman filter method (1.35 km) occurs in the south-westerly flows and regional recirculations. Most likely this is attributable to the more intense mesoscale processes with these synoptic flows. The lowest PBL heights from the extended Kalman filter method (0.73 km) are associated with westerly flows. Some comparisons can be made with Pandolfi et al. (2013), who used a spatial derivative method on ceilometer data. In Pandolfi et al. (2013) the highest PBL heights were observed in the cold Atlantic (1.88 \(\pm \) 0.29 km a.g.l.) airmass, followed by stagnant regional (1.77 \(\pm \) 0.31 km a.g.l.), and north African airmasses (1.57 \(\pm \) 0.43 km a.g.l.).

At the 1.5-km arriving altitude the largest differences between any lidar-based method and radiosoundings occur in north-east and fast west-north-west flows. Both synoptic situations influence an across-the-board underestimation of the PBL height by the lidar methods, by as much as 0.43 km with the variance method.

Cluster groups at the arriving altitudes of 0.5 and 3 km show similar results to those at 1.5 km, except for a few notable features. Synoptic clusters at the 0.5 km altitude are the most complex due to unique mesoscale processes induced by the topography and close proximity to the sea. The extended Kalman filter method outperforms classic methods with a small average underestimation of 0.06 km. At the 3-km arriving altitude we lose the influence of regional recirculations, replaced by slow south-westerly and easterly flows (Fig. 3c). The extended Kalman filter method estimates average PBL heights of 1.17 and 0.86 km, in slow south-westerly and easterly flows, respectively. The low PBL height in easterly flows is possibly due to low-level clouds. The largest differences in PBL height between lidar and radiosoundings occur in easterly flows, with an underestimation around 0.3 km among all methods. This result highlights the possible effects of cloud distortion of the lidar range-corrected signal and its implication on PBL height retrievals.

4.3 Performance Evaluation of WRF Model PBL Schemes

The lidar-extended Kalman filter technique is used to validate PBL heights simulated in the WRF model. Figure 6 shows colour-coded scatter plots of PBL height estimated with the lidar-extended Kalman filter method against those simulated with each PBL parametrization scheme, grouped according to synoptic clusters at 1.5-km altitude. The non-local scheme, ACM2, shows the highest determination coefficient \((R^{2} = 0.33)\) of all PBL schemes tested. Similar results were found in a study by Bossioli et al. (2009) over Athens, Greece, where non-local schemes are found superior to the other schemes tested, favouring strong vertical mixing and transport towards the surface. They found that enhanced mixing in the non-local schemes is caused by larger diffusion coefficients. The two other non-local schemes tested (YSU and TEMF) show the third highest \((R^{2} = 0.22)\) and sixth highest \((R^{2}= 0.18)\) determination coefficients, respectively. The local MYJ scheme performs poorest \((R^{2}= 0.15)\) in this analysis, even though it is well-tested and preferred in previous studies.

Scatter plots between the PBL height diagnosed by the WRF model using eight different PBL schemes and PBL height estimated with the lidar-extended Kalman filter technique. Data points have been colour-coded according to their cluster type arriving at 1.5 km altitude. The 1:1 line (solid red) has been added. Coefficient of determination \((R^{2})\) values are computed based on the total data collection (\(N = 45)\). Units of km

Regional recirculations show the poorest model diagnoses of PBL height, while fast west-north-west and northerly flows show the closest WRF model-simulated PBL height to the lidar-extended Kalman filter estimates. Overall, there is a systematic under-representation of PBL height simulated in the model, with five (YSU, MYNN2, BouLac, UW, and TEMF) of the eight tested schemes showing lower PBL heights than estimates from the lidar. The results at 0.5-km and 3-km arriving altitudes are very similar to 1.5 km, and are not shown here.

The mean value of lidar-extended Kalman filter PBL height and the mean relative bias between WRF model PBL schemes and lidar at each synoptic grouping at 1.5 km altitude is shown in Table 3. PBL schemes within \(\pm \)20 % of the lidar-extended Kalman filter PBL height are highlighted in each synoptic cluster. The ACM2 scheme shows the closest results, with only an 1 % model-simulated overestimate in the total set. Also, the ACM2 scheme is superior in regional recirculations and synoptic flows from the north-east. The MYJ scheme shows the second closest results, with an overall 5 % underestimate by the WRF model; all but one PBL scheme (QNSE) show underestimations. On average, the QNSE scheme overestimates PBL height by 56 % compared with the lidar estimates.

The results are in a stark contrast to those of Pérez et al. (2006), with comparisons of three different PBL schemes from the legacy MM5 model. The study was also conducted over the Western Mediterranean, including the Barcelona geographical area, during a typical summertime case with an absence of large-scale forcing. They discovered that non-local schemes show similar results and have a tendency to overestimate the PBL height when validated with estimates from lidar and radiosoundings. They showed biases ranging from 40 to 72 % and errors from 59 to 77 %, attributed to the scheme-specific methods used to calculate PBL height. The complex topography of the north-east Iberian Peninsula may contribute significantly to the differences observed in the PBL schemes.

4.4 Representative Cases of Most Frequent Synoptic Clusters

Here we present representative days for the four most frequent atmospheric situations, validated with complementary information from satellite images, radiosoundings, mineral dust model simulations, and WRF-simulated synoptic maps. The most frequent synoptic flows over Barcelona are from the north, west, south-west, and east.

4.4.1 Clean Free Troposphere During North and North-West Synoptic Flows

The simplest type of atmospheric flow for PBL height estimation is for a clear delineation between the convective boundary layer and the free troposphere, most often in north and north-west synoptic flows. A representative day for this atmospheric situation is shown in Fig. 7 for 22 March 2009, with synoptic flow from the north at 1.5-km and 3-km altitudes, and from the north-east at 0.5-km altitude. A surface high pressure ridge is situated over the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 7c), with a dry free troposphere confirmed with a radiosounding (not shown).

a Lidar power \(\times \) range-squared (\(\hbox {PR}^2\)) time-height series (arbitrary units) from 1202 to 1233 UTC, with 1-min PBL height (km a.s.l.) estimates from the extended Kalman filter (magenta circles), threshold (black diamonds), variance (black triangles), and WCT (black squares) methods. Radiosonde-estimated PBL height at 1200 UTC is shown with a white dashed line. b WRF model-simulated PBL height (km a.s.l.) with eight PBL schemes. Coincident lidar delineated with black vertical line. c WRF model synoptic sea-level pressure (hPa, shaded contours), and 850-hPa geopotential heights (blue lines) and wind vectors valid at 1200 UTC on 22 March using the YSU PBL scheme

The PBL height estimated with a 1200 UTC radiosounding is 1.28 km; the extended Kalman filter method provides the closest lidar-based estimate to the radiosounding (1.24 km), and is similar to the average for all lidar days in northerly synoptic flows. The WCT method performs the second closest (1.16 km), followed by the threshold (0.97 km) and variance (0.96 km) methods.

Figure 7b shows the diurnal cycle of hourly WRF model-simulated PBL heights with each PBL scheme. The ACM2 scheme simulates the highest daytime maximum PBL height (1.80 km at 1100 UTC and 1200 UTC), while the UW scheme simulates the lowest daytime-maximum (0.70 km at 1100 UTC). The MYJ scheme is closest to the observed values. However, the MYJ and QNSE schemes exhibit higher model-simulated PBL heights in the morning, when other PBL schemes are grouped below 0.6 km. In the evening, the QNSE and TEMF schemes show a slower decay of the PBL height than the other six schemes.

4.4.2 Regional Recirculations at Low Levels

Regional recirculations are especially frequent in summertime when the synoptic pattern is stagnant and mesoscale convective processes dominate. A representative day for this pattern is shown in Fig. 8 for 3 July 2012, with regional recirculations from the east and west, at 0.5 and 1.5 km, respectively. Figure 8c shows a weak surface high pressure centred over the western Mediterranean basin, which confirms a stagnant atmospheric pattern over the north-east Iberian Peninsula.

Same description as in Fig. 7, except for representative case on 3 July 2012

The PBL height estimated from a 1200 UTC radiosounding is 0.91 km, while the extended Kalman filter and threshold methods show similar estimates, around 1.05 km, while the WCT and variance methods (both 1.78 km) follow the additional aerosol layer between 1.5 and 2 km. The additional aerosol layer is quite common at this time of the day in summertime, due to the return airflow induced by interaction between the pre-coastal mountain range and the sea.

Hourly WRF model-simulated PBL heights are shown in Fig. 8b. The highest daytime-maximum PBL heights are simulated by the MYJ and QNSE schemes, around 1.48 km. The lowest daytime-maximum PBL height is associated with the UW scheme (0.74 km at 1200 UTC), as in the previous case. The MYNN2 and BouLac schemes produce 1200 UTC PBL heights closest to the observations. There is a large spread among PBL schemes with the growing PBL in the morning, with the TEMF, QNSE, and MYNN2 schemes showing higher PBL heights than other schemes. The model spread is smaller with respect to the decaying PBL in the evening.

4.4.3 Saharan Dust Episode from West and South-West Synoptic Flows

Advections of Saharan dust from the west and south-west are a common occurrence over the north-east Iberian Peninsula and can occur anytime during the year (Salvador et al. 2014). A representative day (Fig. 9a) is shown for 3 August 2007, with synoptic flow from the west at 3 km, and westerly regional recirculations prevalent at 0.5 and 1.5 km altitudes. A surface synoptic map (Fig. 9c) reveals a stagnant mesoscale pattern with weak west to south-west winds over Catalonia. The dust episode is confirmed using a simulation from the NMMB/BSC-Dust model (Pérez et al. 2011). Dust concentrations greater than \(75\upmu \hbox {g}\,\hbox {m}^{-3}\) with a layer below 4 km a.g.l. are seen with a vertical profile (not shown).

Same description as in Fig. 7, except for representative case on 3 August 2007

PBL height estimated with a radiosounding is 1.43 km, with the extended Kalman filter method providing an estimate (1.5 km) closest to the radiosonde, while the classic methods (\(\hbox {threshold} = 2.41~\hbox {km}, \hbox {WCT} = 2.3~\hbox {km}, \hbox {variance} = 0.97~\hbox {km}\)) have issues determining the correct PBL height. In this complex case the extended Kalman filter method has a significant advantage over classic methods due to its knowledge of the errors of past estimates of PBL height.

Figure 9b shows the hourly PBL height diagnosed by the WRF model. The QNSE scheme simulates the highest daytime-maximum PBL height (1.83 km at 1200 UTC), and is closest to the observations. The lowest daytime-maximum PBL height is produced with the UW scheme (0.94 km at 1300 UTC). The agreement amongst the schemes is much closer than in the previous two cases when analysing the full diurnal cycle.

4.4.4 Influences of Cloud Layers

The final atmospheric scenario that occurs frequently in the north-east Iberian Peninsula are low-level clouds induced by flows from the east. A representative day with clouds near the boundary layer is selected as 22 April 2010 (Fig. 10), with easterly regional recirculations at 0.5 km, easterly flow at 1.5 km, and weak south-west flow at 3 km. Clouds are denoted by the strong return (dark red colours above \(4.5 \times 10^{-3}\) arbitrary units) in the lidar range-corrected signal.

Same description as in Fig. 7, except for representative case on 22 April 2010

The strongly reflective cloud layer observed from 2.0 to 3.5 km can be validated with a radiosounding profile and an infrared satellite image from Meteosat-9 (not shown). The synoptic map (Fig. 10c) shows a low pressure area, with Barcelona situated in the easterly flow ahead of a weather front. The PBL height on this day is the lowest of all cases, with a radiosounding-estimated PBL height of 0.58 km, implying a strong marine influence lowering the PBL. The extended Kalman filter method is the most accurate (0.57 km), while the threshold method (0.38 km) is too low, and the WCT (1.66 km) and variance (2.58 km) methods diagnose the PBL height somewhere below or in the cloud layer.

Hourly WRF model-simulated PBL height is shown in Fig. 10b. The QNSE scheme simulates the highest daytime maximum PBL height (1.14 km at 1200 UTC), while the UW and MYNN2 schemes simulate the lowest daytime-maximum PBL heights (0.41 and 0.50 km at 1200 UTC, respectively). The BouLac and YSU schemes simulate 1200 UTC PBL heights closest to the observations. Unexplained issues are noted with the evening decay of the PBL by the QNSE and MYJ schemes, which simulate sharp increases after 2000 UTC.

4.4.5 Surface Energy Fluxes

The differences in WRF model-simulated PBL heights shown in the previous four representative cases were relatively substantial, sometimes \(>\)200 % between the lowest and highest model-simulated PBL heights. Fluxes between the land surface and the atmosphere are an important component in PBL development. We show a brief analysis (Fig. 11) of the upward sensible heat flux \((\hbox {W m}^{-2})\) for the four representative cases.

Overall, the WRF model-simulated sensible heat flux is within \(\pm \) 25 W m\(^{-2}\) for most of the diurnal cycle, except during the period of maximum solar insolation. The QNSE and TEMF schemes overestimate the sensible heat flux between 100–150 W m\(^{-2}\) when compared with other PBL schemes. The difference is smallest in the case of low-level clouds in the PBL (Fig. 11d).

It is possible that the greater PBL heights simulated in the QNSE scheme are due to large surface heat fluxes simulated by the WRF model. However, large deviations of sensible heat flux with the TEMF scheme do not translate to the PBL heights, which are in the middle of the spread for all cases.

In addition, differences in the PBL height among the schemes may be attributed to the entrainment formulations in the schemes, which are not explored here. Shin and Hong (2011) found that the non-local ACM2 scheme performed well in the unstable PBL, based on the schemes explicit treatment of the entrainment flux as proportional to the surface flux. However, this is not a unique feature to this scheme.

5 Conclusions

We have achieved three primary objectives: first, we used a cluster analysis algorithm to determine seven distinct synoptic flow types over the north-east Iberian Peninsula. The synoptic cluster groups are found to be similar at 0.5-km and 1.5-km arriving altitudes, with minor changes at 3-km altitude. The analysis confirms that the most predominant synoptic cluster over the north-east Iberian Peninsula is the regional recirculations from the east or west, and that the identified synoptic flows have multiple aerosol layers.

Secondly, methods to obtain the planetary boundary-layer (PBL) height from lidar were compared and validated at 1200 UTC over a 7-year period. A novel approach using an extended Kalman filter is compared with classic methods found in the literature. The comparison of PBL height estimates provided by traditional and advanced lidar-based approaches was performed for seven objectively determined synoptic flows at different arriving altitudes representing within the PBL, at the top of the PBL, and in the free troposphere.

An advanced lidar-based approach utilizes an extended Kalman filter to time-adaptively estimate PBL height within a range from 0.79 to 1.6 km, similar to previous studies. Moreover, the adaptive extended Kalman filter approach tends to capture the PBL height evolution quite accurately. PBL height retrieved by the extended Kalman filter technique has a strong determination coefficient \((R^{2} = 0.96)\) when compared with PBL height estimates from daily daytime radiosonde launches. Classic lidar-based methods showed much weaker correlations, even when gross outliers outside one standard deviation were removed prior to the calculations. In contrast to the extended Kalman filter approach, this is because classic methods do not rely on past estimates and associated statistical and a priori information to yield present-time estimates but on the instantaneous measurement record, instead. Besides, classic methods comparatively require a much longer time averaging and range smoothing to perform reliably and are usually limited to single-layer scenes.

Representative cases for a clean free troposphere, regional recirculations, Saharan dust episodes, and low-level cloud layers highlight the adaptability of the extended Kalman filter technique when compared with classic methods. Except for cases of a clean free troposphere, the classic methods typically have issues when multiple aerosol layers are present. If the user selects a proper threshold value the threshold method performs second best to the extended Kalman filter.

An approach using the extended Kalman filter proves promising for continuous and automatic observation of PBL height from lidar measurements. The extended Kalman filter technique can be applied directly to the lidar range-corrected signal. It has been found that optimal parameters must be chosen for the state vector initialization for the extended Kalman filter method to track PBL height accurately, depending on the instrument type.

With the final objective, PBL heights simulated in the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model were validated against the lidar-extended Kalman filter estimates. WRF model-simulated PBL heights were evaluated using eight unique PBL schemes. Test simulations with the WRF model reveal a clear favour to non-local PBL schemes, with the ACM2 scheme showing the closest correlation to lidar-extended Kalman filter estimates. Surprisingly, the widely-tested local MYJ scheme showed the weakest correlation coefficients. Ambiguous results are found when evaluating the model-simulated PBL heights under the most representative synoptic situations. In all cases, the local UW scheme produced the lowest daytime maximum PBL height. In the least complex case of a clean free troposphere the MYJ scheme showed the closest model-simulated PBL height to the observations. With more complex cases such as regional recirculations and effects due to Saharan dust intrusions the results are varied, with no clear favourite scheme.

WRF model-simulated sensible heat flux between the land surface and the atmosphere confirmed a possible reason for the high PBL heights simulated with the QNSE scheme. However, other PBL schemes showed very similar model simulations of sensible heat flux. The large differences in PBL heights among the schemes could be attributable to one of two primary components: first, and possibly the largest, are the operational definitions of PBL height in the individual schemes. Secondly, differences in the entrainment behaviour among the PBL schemes could be a factor.

Future work should include an evaluation of WRF model PBL schemes using the lidar-extended Kalman filter method at other locations, with comparison between a complex, coastal site similar to Barcelona and a continental site (e.g., Cabauw, The Netherlands). It is possible that the skill of PBL schemes is dependent on entrainment fluxes, but also on the effect of mesoscale horizontal flow. In addition, with the advantage of reliable tracking of diurnal PBL height the lidar-extended Kalman filter method can be employed as an assimilation tool for PBL height simulations in the WRF model and other numerical weather prediction models.

References

Angevine WM, Jiang H, Mauritsen T (2010) Performance of an eddy diffusivity-mass flux scheme for shallow cumulus boundary layers. Mon Weather Rev 138:2895–2912

Baars H, Ansmann A, Engelmann R, Althausen D (2008) Continuous monitoring of the boundary-layer top with lidar. Atmos Chem Phys 8(23):7281–7296

Baldasano JM, Cremades L, Soriano C (1994) Circulation of air pollutants over the Barcelona geographical area in summer. In: Proceedings of sixth European symposium physico-chemical behaviour of atmospheric pollutants. Report EUR 15609/1 EN, pp 474-479

Blackadar AK (1978) Modeling pollutant transfer during daytime convection. In: Preprints fourth symposium on atmospheric turbulence, diffusion, and air quality. American Meteorological Society, Reno, NV, pp 443–447

Boers R, Eloranta EW (2006) Lidar measurements of the atmospheric entrainment zone and the potential temperature jump across the top of the mixed layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 34(4):357–375

Borge R, Alexandrov V, José del Vas J, Lumbreras J, Rodríguez E (2008) A comprehensive sensitivity analysis of the WRF model for air quality applications over the Iberian Peninsula. Atmos Environ 42(37):8560–8574

Bosenberg J, Ansmann A, Baldasano J, Balis D, Bockmann C, Calpini B, Chaikovsky A, Flamant P, Hagard A, Mitev V, Papayannis A, Pelon J, Resendes D, Schneider J, Spinelli N, Vaughan TTG, Visconti G, Wiegner M (2001) EARLINET: a European Aerosol Research Lidar Network. In: Laser remote sensing of the atmosphere, selected papers of the 2001 international laser radar conference, pp 155–158

Bossioli E, Tombrou M, Dandou A, Athanasopoulou E, Varotos K (2009) The role of planetary boundary-layer parameterizations in the air quality of an urban area with complex topography. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 131:53–72

Bougeault P, Lacarrere P (1989) Parameterization of orography-induced turbulence in a mesobeta-scale model. Mon Weather Rev 117:1872–1890

Bretherton C, Park S (2009) A new moist turbulence parameterization in the Community Atmosphere Model. J Clim 22:3422–3448

Brown RG, Hwang PYC (1982) Introduction to random signals and applied Kalman filtering. Wiley, New York, 502 pp

Chen F, Mitchell K, Schaake J, Xue Y, Pan H, Koren V, Duan Y, Ek M, Betts A (1996) Modeling of land-surface evaporation by four schemes and comparison with FIFE observations. J Geophys Res 101:7251–7268

Collis R, Russell P (1976) Lidar measurements of particles and gases by elastic backscattering and differential absorption. In: Hinkley E (ed) Laser monitoring of the atmosphere. Springer, New York, pp 71–102

Comerón A, Sicard M, Rocadenbosch F (2013) Wavelet correlation transform method and gradient method to determine aerosol layering from lidar returns: some comments. J Atmos Ocean Technol 30(6):1189–1193

Draxler RR, Rolph GD (2013) HYSPLIT (HYbrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory) model access via NOAA ARL READY website. NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, College Park, MD. http://www.arl.noaa.gov/HYSPLIT.php

Dudhia J (1989) Numerical study of convection observed during the Winter Monsoon Experiment using a mesoscale two-dimensional model. J Atmos Sci 46:3077–3107

Dudhia J (1993) A non-hydrostatic version of the Penn State-NCAR mesoscale model: validation tests and simulation of an Atlantic cyclone and cold front. Mon Weather Rev 121:1493–1513

Flamant C, Pelon J, Flamant PH, Durand P (1997) Lidar determination of the entrainment zone thickness at the top of the unstable marine atmospheric boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 83(2):247–284

Gan CM, Wu Y, Madhavan BL, Gross B, Moshary F (2011) Application of active optical sensors to probe the vertical structure of the urban boundary layer and assess anomalies in air quality model PM2.5 forecasts. Atmos Environ 45(37):6613–6621

Gent PR, Danabasoglu G, Donner LJ, Holland MM, Hunke EC, Jayne SR, Lawrence DM, Neale RB, Rasch PJ, Vertenstein M, Worley PH, Yang Z, Zhang M (2011) The Community Climate System Model Version 4. J Clim 24(19):4973–4991. doi:10.1175/2011JCLI4083.1

Gonçalves M, Jiménez-Guerrero P, Baldasano JM (2009) Contribution of atmospheric processes affecting the dynamics of air pollution in south-western Europe during a typical summertime photochemical episode. Atmos Chem Phys 9:849–864

Hennemuth B, Lammert A (2006) Determination of the atmospheric boundary layer height from radiosonde and lidar backscatter. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 120(1):181–200

Holtslag AAM, De Bruijn EIF, Pan HL (1990) A high resolution air mass transformation model for short-range weather forecasting. Mon Weather Rev 118(8):1561–1575

Hong SY, Pan HL (1996) Nonlocal boundary layer vertical diffusion in a Medium-Range Forecast model. Mon Weather Rev 124:2322–2339

Hong SY, Dudhia J, Chen S-H (2004) A revised approach to ice microphysical processes for the bulk parameterization of clouds and precipitation. Mon Weather Rev 132:103–120

Hong SY, Noh Y, Dudhia J (2006) A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Mon Weather Rev 134:2318–2341

Janjic Z (1990) The step-mountain coordinate: physical package. Mon Weather Rev 118(7):1429–1443

Janjic ZI (2002) Nonsingular implementation of the Mellor–Yamada Level 2.5 scheme in the NCEP meso model. NCEP Office Note 437, 61 pp

Jorba O, Pérez C, Rocadenbosch F, Baldasano J (2004) Cluster analysis of 4-day back trajectories arriving in the Barcelona area, Spain, from 1997 to 2002. J Appl Meteorol 43(6):887–901

Kain JS (2004) The Kain–Fritsch convective parameterization: an update. J Appl Meteorol 43:170–181

Lange D, Tiana-Alsina J, Saeed U, Tomas S, Rocadenbosch F (2013) Atmospheric boundary layer height monitoring using a Kalman filter and backscatter lidar returns. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote 52(8):4717–4728

Martilli A, Clappier A, Rotach MW (2002) An urban surface exchange parameterisation for mesoscale models. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 104:261–304

Melfi SH, Spinhirne JD, Chou SH, Palm SP (1985) Lidar observations of vertically organized convection in the planetary boundary layer over the ocean. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 24(8):806–821

Menut L, Flamant C, Pelon J, Flamant PH (1999) Urban boundary-layer height determination from lidar measurements over the Paris area. Appl Opt 38(6):945–954

Mlawer EJ, Taubman SJ, Brown PD, Iacono MJ, Clough SA (1997) Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmospheres: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. J Geophys Res 102:16663–16682

Nakanishi M, Niino H (2006) An improved Mellor–Yamada level-3 model: its numerical stability and application to a regional prediction of advection fog. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 119:397–407

NCEP (National Centers for Environmental Prediction)/National Weather Service/NOAA/U.S. Department of Commerce: NCEP FNL Operational Model Global Tropospheric Analyses, continuing from July 1999, Research Data Archive at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Computational and Information Systems Laboratory. doi:10.5065/D6M043C6. Last accessed 10 May 2014

Pal S, Devara PCS (2012) A wavelet-based spectral analysis of long-term time series of optical properties of aerosols obtained by lidar and radiometer measurements over an urban station in Western India. J Atmos Sol-Terr Phy 84:75–87

Pal S, Behrendt A, Wulfmeyer V (2010) Elastic-backscatter-lidar-based characterization of the convective boundary layer and investigation of related statistics. Ann Geophys 28(3):825–847

Pandolfi M, Martucci G, Querol X, Alastuey A, Wilsenack F, Frey S, D’owd CD, Dall’Osto M (2013) Continuous atmospheric boundary layer observations in the coastal urban area of Barcelona, Spain. Atmos Chem Phys Discuss 13:345–377

Pérez C, Jiménez P, Jorba O, Sicard M, Baldasano JM (2006) Influence of the PBL scheme on high-resolution photochemical simulations in an urban coastal area over the Western Mediterranean. Atmos Environ 40(27):5274–5297

Pérez C, Haustein K, Janjic Z, Jorba O, Hunees N, Baldasano JM, Black T, Basart S, Nickovic S, Miller L, Perlwitz JP, Schulz M, Thomson M (2011) Atmospheric dust modeling from meso to global scales with the online NMMB/BSC-Dust model—part 1: model description, annual simulations and evaluation. Atmos Chem Phys 11:13001–13027. doi:10.5194/acp-11-13001-2011

Pichelli E, Ferretti R, Cacciani M, Siani AM, Ciardini V, Di Iorio T (2014) The role of urban boundary layer investigated with high-resolution models and ground-based observations in Rome area: a step towards understanding parameterization potentialities. Atmos Meas Tech 7(1):315–332

Pleim JE (2007) A combined local and non-local closure model for the atmospheric boundary layer. Part 1: model description and testing. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 46:1383–1395

Quan J, Gao Y, Zhang Q, Tie X, Cao J, Han S, Meng J, Chen P, Zhao D (2013) Evolution of planetary boundary layer under different weather conditions, and its impact on aerosol concentrations. Particuology 11(1):34–40

Richardson H, Basu S, Holtslag AAM (2013) Improving stable boundary-layer height estimation using a stability-dependent critical bulk Richardson number. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 148(1):93–109

Rocadenbosch F, Vázquez G, Comerón A (1998) Adaptive filter solution for processing lidar returns: optical parameter estimation. Appl Opt 37(30):7019–7034

Rocadenbosch F, Soriano C, Comerón A, Baldasano JM (1999) Lidar inversion of atmospheric backscatter and extinction-to-backscatter ratios by use of a Kalman filter. Appl Opt 38(15):3175–3189

Rocadenbosch F, Sicard M, Comerón A, Baldasano JM, Rodrıguez A, Agishev R, Munoz C, Lopez MA, Garcia-Vizcaino D (2002) The UPC scanning Raman lidar: An engineering overview. In: Lidar remote sensing in atmospheric and earth sciences—reviewed and revised papers presented at the 21st ILRC, pp 69–70

Salvador P, Alonso S, Pey J, Artíñano B, de Bustos JJ, Alastuey A, Querol X (2014) African dust outbreaks over the western Mediterranean basin: 11 year characterization of atmospheric circulation patterns and dust source areas. Atmos Chem Phys Discuss 14:5495–5533

Seaman NL (2000) Meteorological modeling for air-quality assessments. Atmos Environ 34:2231–2259

Seibert P, Beyrich F, Gryning SE, Joffre S, Rasmussen A, Tercier P (2000) Review and intercomparison of operational methods for the determination of the mixing height. Atmos Environ 34(7):1001–1027

Shin HH, Hong S-Y (2011) Intercomparison of planetary boundary-layer parametrizations in the WRF model for a single day from CASES-99. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 139(2):261–281

Sicard M, Pérez C, Rocadenbosch F, Baldasano JM, García-Vizcaino D (2006) Mixed-layer depth determination in the Barcelona coastal area from regular lidar measurements: methods, results and limitations. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 119(1):135–157

Sicard M, Rocadenbosch F, Reba MNM, Comerón A, Tomás S, García-Vízcaino D, Batet O, Barrios R, Kumar D, Baldasano JM (2011) Seasonal variability of aerosol optical properties observed by means of a Raman lidar at an EARLINET site over Northeastern Spain. Atmos Chem Phys 11(1):175–190

Skamarock WC, Klemp JB (2008) A time-split nonhydrostatic atmospheric model for weather research and forecasting applications. J Comput Phys 227(7):3465–3485

Skamarock WC, Klemp JB, Dudhia J, Gill DO, Barker DM, Duda MG, Huang X-Y, Wang W, Powers JG (2008) A description of the advanced research WRF Version 3. NCAR Tech Note, 125 pp

Stull RB (1988) An introduction to boundary layer meteorology. Kluwer, Dordrecht, 670 pp

Sukoriansky S, Galperin B, Perov V (2005) Application of a new spectral theory of stably stratified turbulence to atmospheric boundary layers over sea ice. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 117(2):231–257

Tewari M, Chen F, Wang W, Dudhia J, LeMone MA, Mitchell K, Ek M, Gayno G, Wegiel J, Cuenca RH (2004) Implementation and verification of the unified NOAH land surface model in the WRF model. In: 20th conference on weather analysis and forecasting/16th conference on numerical weather prediction, pp 11–15

Upton G, Cook I (2008) A dictionary of statistics, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, UK, 496 pp

Acknowledgments

This research has been financed by ITARS (http://www.itars.net), European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013): People, ITN Marie Curie Actions Programme (2012–2016) under grant agreement no 289923. WRF simulations were executed on the MareNostrum supercomputer at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center, under grants SEV-2011-00067 of Severo Ochoa program and CGL-2013-46736-R, awarded by the Spanish Government. Also, credit (UE FP7-INFRA-2010-1.1.16) to the ACTRIS (Aerosols, Clouds, and Trace gases Research InfraStructure) network. The authors gratefully acknowledge the NOAA Air Resources Laboratory (ARL) for the provision of the HYSPLIT transport and dispersion model and/or READY website (http://www.ready.noaa.gov) used in this publication. A special thanks to Albert Soret and Kim Serradell for their assistance with the cluster analysis algorithm. Finally, thanks to the Meteorological Service of Catalonia for providing the radiosonde data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Banks, R.F., Tiana-Alsina, J., Rocadenbosch, F. et al. Performance Evaluation of the Boundary-Layer Height from Lidar and the Weather Research and Forecasting Model at an Urban Coastal Site in the North-East Iberian Peninsula. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 157, 265–292 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-015-0056-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-015-0056-2