Abstract

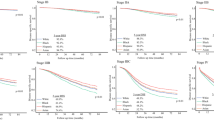

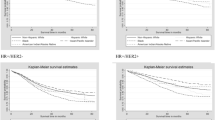

Breast cancer mortality rates in South Carolina (SC) are 40 % higher among African-American (AA) than European-American (EA) women. Proposed reasons include race-associated variations in care and/or tumor characteristics, which may be subject to income effects. We evaluated race-associated differences in tumor biologic phenotype and stage among low-income participants in a government-funded screening program. Best Chance Network (BCN) data were linked with the SC Central Cancer Registry. Characteristics of breast cancers diagnosed in BCN participants aged 47–64 years during 1996–2006 were abstracted. Race-specific case proportions and incidence rates based on estrogen receptor (ER) status and histologic grade were estimated. Among 33,880 low-income women accessing BCN services, repeat breast cancer screening utilization was poor, especially among EAs. Proportionally, stage at diagnosis did not differ by race (607 cancers, 53 % among AAs), with about 40 % advanced stage. Compared to EAs, invasive tumors in AAs were 67 % more likely (proportions) to be of poor-prognosis phenotype (both ER-negative and high-grade); this was more a result of the 46 % lesser AA incidence (rates) of better-prognosis (ER+ lower-grade) cancer than the 32 % greater incidence of poor-prognosis disease (p values <0.01). When compared to the general SC population, racial disparities in poor-prognostic features within the BCN population were attenuated; this was due to more frequent adverse tumor features in EAs rather than improvements for AAs. Among low-income women in SC, closing the breast cancer racial and income mortality gaps will require improved early diagnosis, addressing causes of racial differences in tumor biology, and improved care for cancers of poor-prognosis biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

African-American

- BCCEDP:

-

Breast and Cervical Early Detection Program

- BCN:

-

Best Chance Network

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- EA:

-

European-American

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- ER-:

-

ER-negative

- ER+:

-

ER-positive

- G:

-

Grade

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- MAR:

-

Missing at random

- MCAR:

-

Missing completely at random

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- RR:

-

Incidence rate ratio (AA/EA)

- SC:

-

South Carolina

- SCCCR:

-

SC Central Cancer Registry

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- US:

-

United States

References

South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control: South Carolina Community Assessment Network. http://scangis.dhec.sc.gov/scan/cancer2/mortinput.aspx. Accessed 13 June 2012

American Cancer Society (2011) Breast cancer facts & figures 2011–2012. American Cancer Society, Inc., Atlanta

Cunningham JE, Butler WM (2004) Racial disparities in female breast cancer in South Carolina: clinical evidence for a biological basis even in small tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 88:161–176

Cunningham JE, Montero AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, Berkel HJ, Ely B (2010) Racial differences in the incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by combined histologic grade and hormone receptor status. Cancer Causes Control 21(3):399–409

Adams SA, Hebert JR, Bolick-Aldrich S, Daguise VG, Mosley CM, Modayil MV, Berger SH, Teas J, Mitas M, Cunningham JE, Steck SE, Burch J, Butler WM, Horner M-JD, Brandt HM (2006) Breast cancer disparities in South Carolina: early detection, special programs and descriptive epidemiology. J S C Med Assoc 102(7):231–239

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA et al (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. J Am Med Assoc 295:2492–2502

Anderson WF, Reiner AS, Matsuno RK et al (2007) Shifting breast cancer trends in the United States. J Clin Oncol 25:3923–3929

Ursin G, Bernstein L, Wang Y et al (2004) Reproductive factors and risk of breast carcinoma in a study of white and African-American women. Cancer 101:353–362

Althuis MD, Fergenbaum JH, Garcia-Closas M et al (2004) Etiology of hormone receptor-defined breast cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarks Prev 13:1558–1568

Ma H, Bernstein L, Pike MC et al (2006) Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk according to joint estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Breast Cancer Res 8:R43. doi:10.1186/bcr1525

Garcia-Closas M, Hall P, Nevanlinna H et al (2008) Heterogeneity of breast cancer associations with five susceptibility loci by clinical and pathological characteristics. PLoS Genet 4(4):e1000054

Maiti B, Kundranda MN, Spiro TP et al (2010) The association of metabolic syndrome with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 121:479–483

Singh SK, Tan QW, Brito C et al (2010) Insulin-like growth factors I and II receptors in the breast cancer survival disparity among African-American women. Growth Horm IGF Res 20:245–254

Yang X, Chang-Claude J, Goode EL et al (2011) Associations of breast cancer risk factors with tumor subtypes: a pooled analysis from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:250–263

Harper S, Lynch J, Meersman SC et al (2009) Trends in area-socioeconomic and race-ethnic disparities in breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, screening, mortality, and survival among women ages 50 years and over (1987–2005). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarks Prev 18:121–131

Krieger N, Chen JT, Ware JH et al (2008) Race/ethnicity and breast cancer estrogen receptor status: impact of class, missing data, and modeling assumptions. Cancer Causes Control 19:1305–1318

Campbell RT, Li X, Dolecek TA, Barrett RE, Weaver KE, Warnecke RB (2009) Economic, racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer in the US: towards a more comprehensive model. Health Place 15:855–864

Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA et al (2009) Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control 20:417–435

South Carolina Best Chance Network. http://www.scdhec.gov/health/chcdp/cancer/bcn.htm. Accessed 15 June 2012

Smith ER, Adams SA, Prabhu Das I, Bottai M, Fulton J, Hebert JR (2008) Breast cancer survival among economically disadvantaged women: the influences of delayed diagnosis and treatment on mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:2882–2890

Gorin SS, Heck JE, Cheng B, Smith SJ (2006) Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by racial/ethnic group. Arch Intern Med 166:2244–2252

South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control: South Carolina Central Cancer Registry. http://www.scdhec.gov/co/phsis/biostatistics/SCCCR/AboutARegistry.htm. Accessed 15 Mar 2011

SEER Summary Staging Manual 2000. http://training.seer.cancer.gov/ss2k/2000/. Accessed 15 June 2012

van Buuren S, Brand JPL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Rubin DB (2006) Fully conditional specification in multivariate imputation. J Stat Comput Simul 76:1049–1064

van Buuren S (2007) Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 16:219–242

Rubin DB (1987) Multiple imputation for non-response in surveys. Wiley, New York

Schafer JL (1997) Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman & Hall, London

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009) Compressed mortality, 1999–2006. Series 20 No. 2L. http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html. Accessed 12 Aug 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2003) Compressed mortality, 1979–1998, Series 20, No. 2E. http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd9.html. Accessed 12 Aug 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2008) Bridged-race population estimates (vintage 2008). http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-v2008.html. Accessed 31 Aug 2010

Boyle P, Parkin DM (1991) Statistical methods for registries. In: Jensen OM, Parkin DM, MacLennan R et al (eds) Cancer registration: principles and methods. Scientific publication No. 95. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, pp 128–158

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011) Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45(3):1–67

R Development Core Team (2011) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 04 May 2012

Lobb R, Ayanian JZ, Allen JD, Emmons KM (2010) Stage of breast cancer at diagnosis among low-income women with access to mammography. Cancer 116(23):5487–5496

Enewold L, Zhou J, McGlynn KA et al (2012) Racial variation in tumor stage at diagnosis among Department of Defense beneficiaries. Cancer 118(5):1397–1403. doi:10.1002/cncr.26208

Lawson HW, Henson R, Bob JK, Kaeser MK (2000) Implementing recommendations for the early detection of breast and cervical cancer among low-income women. MMWR Recomm Rep 49(RR-2):37–55

Taplin SH, Ichikawa L, Yood MU et al (2004) Reason for late-stage breast cancer: absence of screening or detection, or breakdown in follow-up? J Natl Cancer Inst 96:1518–1527

American Cancer Society (2009) Breast cancer facts & figures 2009–2010. American Cancer Society, Inc., Atlanta

Ward EM, Fedewa SA, Cokkinides V et al (2010) The association of insurance and stage at diagnosis among patients aged 55 to 74 in the national cancer database. Cancer J 16:614–621

Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N et al (2006) Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med 144:541–553

Hahn KM, Bondy ML, Selvan M et al (2007) Factors associated with advanced disease stage at diagnosis in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 166:1035–1044

Sassi F, Luft HS, Guadagnoli E (2006) Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in female breast cancer: screening rates and stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health 96:2165–2172

Wang F et al (2008) Late stage breast cancer diagnosis and health care access in Illinois. Prof Geogr 60:54–69

Dai D (2010) Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place 16:1038–1052

Dunn BK, Agurs-Collins T, Browne D et al (2010) Health disparities in breast cancer: biology meets socioeconomic status. Breast Cancer Res Treat 121:281–292

Phipps AI, Chlebowski RT, Prentice R et al (2011) Body size, physical activity, and risk of triple-negative and estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarks Prev 20(3):454–463

Schular LA, Auger AP (2010) Psychosocially influenced cancer: diverse early-life stress experiences and links to breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res 3:1365–1370

Butow PN, Hiller JE, Price MA et al (2000) Epidemiological evidence for a relationship between life events, coping style, and personality factors in the development of breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 49:169–181

Michael YL, Carlson NE, Chlebowski RT et al (2009) Influence of stressors on breast cancer incidence in the Women’s Health Initiative. Health Psychol 28:137–146

McLafferty S, Wang F (2009) Rural reversal? Cancer 115:2755–2764

Barry J, Breen N, Barrett M (2012) Significance of increasing poverty levels for determining late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in 1990 and 2000. J Urban Health 89(4):614–627

Adams SA, Smith ER, Hardin J et al (2009) Racial differences in follow-up of abnormal mammography findings among economically disadvantaged women. Cancer 115:5788–5797

Acknowledgments

We particularly thank Irene Prabhu Das, PhD (NIH) for bringing our attention to the need to examine race-associated differences in incidence using BCN data. We also thank Phoenix Do, PhD (University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health) for help with the geospatial considerations and editorial assistance. Thanks are also due to Dianne Lydiard, PhD (SC BCN), to Susan Bolick, MSPH, CTR, and the staff of the SCCCR (Margaret Ehlers, MSPH, and Deborah Hurley, MSPH) for providing the data, and to Mike Byrd, PhD (University of South Carolina) and Anthony Alberg, PhD (Medical University of South Carolina) for their encouragement. JEC and CAW were partially supported by general funds from the Hollings Cancer Center at the Medical University of South Carolina. JEC and TB-E were partially supported by general funds from the University of South Carolina. JEC and EGH were partially supported by NIH grant number 5R03CA137826-02. BCN data were provided by the SC BCCEDP funded through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National BCCEDP grant number 5U58DP000770-05.

Conflict of interest

The authors state they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study presented here complies with the current laws of the US, in which it was performed. This study has not been presented outside the institutions of the authors. Some of this study was conducted by Ms. Tiffany Baker-Elamin toward her MSPH Thesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This manuscript is dedicated to one of the authors, Ms. Tiffany Barker-Elamin, MSPH, whose thesis formed the basis for this study, and whose recent death is mourned by all who knew her.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cunningham, J.E., Walters, C.A., Hill, E.G. et al. Mind the gap: racial differences in breast cancer incidence and biologic phenotype, but not stage, among low-income women participating in a government-funded screening program. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137, 589–598 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2305-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2305-0