Abstract

Social entrepreneurship increasingly involves collective, voluntary organizing efforts where success depends on generating and sustaining members’ participation. To investigate how such participatory social ventures achieve member engagement in pluralistic institutional settings, we conducted a qualitative, inductive study of German Renewable Energy Source Cooperatives (RESCoops). Our findings show how value tensions emerge from differences in RESCoop members’ relative prioritization of community, environmental, and commercial logics, and how cooperative leaders manage these tensions and sustain member participation through temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise strategies. We unpack the mechanisms by which each strategy enables members to justify organizational decisions that violate their personal value priorities and demonstrate their varying implications for organizational growth. Our findings contribute new insights into the challenges of collective social entrepreneurship, the capacity of hybrid organizing strategies to mitigate value concessions, and the importance of logic combinability as a key dimension of pluralistic institutional settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extant research on social entrepreneurship tends to focus on formal employment organizations that pursue social missions through commercial ventures (Smith et al. 2013; Battilana and Lee 2014; Battilana et al. 2017). Yet many forms of social entrepreneurship involve collective organizing efforts that depend on voluntary participation rather than formal employment and that pursue a triple rather than double bottom line. Examples include community transformation initiatives in the developing world (Haugh and Talwar 2016; Pless and Appel 2012), sustainability alliances (Bowen et al. 2018), and cross-sector partnerships (Nicholls and Huybrechts 2016; Sharma and Bansal 2017). Indeed, some scholars have argued that collaborative partnerships are required to produce effective solutions to large-scale social problems (Sud et al. 2009).

Despite the importance of collective, voluntary forms of social entrepreneurship, extant research offers limited insight into the challenges involved and how to manage them. Studies of social enterprise and hybridity tend to emphasize the twin challenges of preventing internal conflict among employees (e.g., Battilana and Dorado 2010; Battilana et al. 2015) and gaining support from diverse external stakeholder groups while avoiding mission drift (e.g., Pache and Santos 2013b; Ramus and Vaccaro 2017). Yet collective, voluntary organizing initiatives often have few formal employees and must instead work to gain and sustain the participation of members who are not dependent on the organization. Research on worker cooperatives, collectivist organizations, and communities highlights the importance of sustaining member participation for long-term success (e.g., Kanter 1972; Rothschild-Whitt 1979; O’Mahony and Lakhani 2011). However, this work does not explain how to do so when a collective pursues multiple and seemingly competing objectives, as in the case of social entrepreneurship initiatives with a double or triple bottom line.

To develop new insight into how collective, voluntary social entrepreneurship initiatives sustain member participation, we conducted a qualitative, inductive study of German Renewable Energy Source Cooperatives (RESCoops). RESCoops use a cooperative legal structure to pursue energy projects that meet community, environmental, and commercial objectives, attracting a diverse group of community organizers, environmental activists, local banks and municipalities, and private individuals as member-investors. Drawing on interview, archival, and observational data from eight RESCoops, we find that while members agree on RESCoops’ pursuit of community, environmental, and commercial objectives, they disagree on the relative importance of these objectives, creating value tensions in the context of specific project decisions. RESCoops manage these value tensions through strategies of temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise. These strategies differ in how they enable members to justify project decisions that do not align with their personal value priorities, with varying implications for organizational growth trajectories.

Our study joins other recent work that seeks to bring values back into institutional theorizing (Kraatz et al. 2010; Kraatz 2015; Vaccaro and Palazzo 2015) and highlights how an ethics perspective can advance theory on social entrepreneurship and hybrid organizing. In particular, we contribute new insights into the nature of the challenges faced by collective, voluntary social enterprises in gaining and sustaining member participation, the capacity of hybrid organizing strategies to mitigate members’ dissatisfaction arising from personal value concessions, and the importance of logic combinability as a key dimension of pluralistic institutional contexts.

Social Entrepreneurship as a Collective, Participatory Organizing Process

Research on social entrepreneurship has tended to focus on formal employment organizations that pursue social missions through commercial ventures (Smith et al. 2013; Battilana and Lee 2014). Examples include work integration organizations that hire beneficiaries as employees (Pache and Santos 2013b; Ramus et al. 2016; Ramus and Vaccaro 2017; Smith and Besharov, forthcoming) and microfinance organizations that employ loan officers tasked with delivering returns for investors while helping their clients escape poverty (Battilana and Dorado 2010; Zhao and Wry 2016). Studies highlight how juxtaposing social and commercial missions within a single organization can foster novel solutions to seemingly intractable societal problems, while also recognizing the significant challenges social enterprises face in realizing this potential (e.g., Tracey et al. 2011). One stream of research emphasizes the potential for internal conflict to emerge between sub-groups of employees whose professional values and identities align with the social and commercial sides of the organization, respectively. As Battilana and Dorado (2010) show in their study of two microfinance organizations, conflict can ultimately become intractable, leading to declining organizational performance. Studies also explore how organizations can mitigate detrimental conflict, for example through hiring and socialization (Battilana and Dorado 2010), spaces of negotiation (Battilana et al. 2015), formalization and collaboration practices (Canales 2014; Ramus et al. 2016), and pluralist managers (Besharov 2014).

A second stream of research emphasizes external challenges of gaining legitimacy and resources from stakeholders who adhere to either a social welfare or commercial logic. Over time, such challenges create a risk of “mission drift” as organizations conform to the expectations of stakeholders on whom they are more dependent for resources (Ebrahim et al. 2014). Research points to varied strategies and practices for avoiding mission drift and sustaining dual social and commercial missions, including governance structures (Ebrahim et al. 2014), stakeholder engagement and social accounting (Ramus and Vaccaro 2017), selective coupling of practices valued by different stakeholder groups (Pache and Santos 2013b), and managerial sensemaking (Jay 2013). Studies have also started to examine these challenges and responses longitudinally, showing how dedicated expertise, structures, and relationships associated with social and commercial missions, coupled with leaders’ paradoxical cognitive frames, can enable organizations to dynamically shift between social and commercial missions while sustaining both over time (Smith and Besharov, forthcoming). Taken as a whole, both streams of research provide important insights into how organizations pursuing both social and commercial missions can avoid internal conflict and mission drift to sustain their duality over time.

By focusing on formal employment organizations with dual missions, however, extant research has overlooked important forms of social entrepreneurship, notably collective social entrepreneurship involving “collaboration amongst similar as well as diverse [organizational and individual] actors for the purpose of applying business principles to solving social problems” (Montgomery et al. 2012, p. 376). Such collaborations often cross sectoral boundaries, involving individuals and organizations from government, business, and nonprofit contexts. Collective social entrepreneurship is therefore well suited to address community and environmental issues that require cooperation of diverse participants for successful resolution (Haugh 2007; Peredo and Chrisman 2006; Jennings et al. 2013). To do so, collective social entrepreneurship initiatives tend to rely on voluntary participation and commitment from a broad base of individual and organizational members, rather than on formal hierarchical control. For example, the social enterprise Gram Vikas seeks to create an “equitable and sustainable society” by working to transform deeply entrenched patterns of social relations in rural Indian villages (Pless and Appel 2012). Because this participatory initiative focuses on transforming an entire community system, it emphasizes the empowerment of intended beneficiaries through participation in a collective organizing process. In Gram Vikas’ water and sanitation program, for example, all villagers participate in a set of democratic, self-governing institutions. While Gram Vikas facilitates the process of setting up these institutions, they are governed by and for the villagers (Pless and Appel 2012).

The emphasis on voluntary participation and the absence of hierarchical authority structures in collective social entrepreneurship initiatives may render inapplicable employment-based strategies for delivering on multiple missions. For example, using hiring and socialization practices to manage divergent employee values (Battilana and Dorado 2010) requires direct managerial control over organizational members. As Santos (2012) notes, the philosophy of control around which formal employment organizations tend to operate contrasts with the empowerment focus of participatory collectives. It is thus unclear whether theoretical insights gained in employment-based social enterprises transfer to collective social entrepreneurship initiatives.

Although research on social entrepreneurship has not focused extensively on collective, voluntary organizing processes, other work in organizational theory offers preliminary insights. Early studies of worker cooperatives and collectivist organizations (Kanter 1972; Swidler 1979; Rothschild and Whitt 1986; Rothschild-Whitt 1979; Whyte and Whyte 1988) and more recent work on community forms of organizing (Adler 2001; O’Mahony and Ferraro 2007; O’Mahony and Lakhani 2011; Seidel and Stewart 2011) point to sustaining member participation as a key challenge. Members tend to join collectives such as alternative schools (Swidler 1979), arts and cultural initiatives (Chen 2009), and political advocacy organizations (Jasper 1997; Polletta and Jasper 2001) in order to realize their values and identities, which often arise from strong ethical ideals. In order for members to continue their support and engagement, it is thus of critical importance that they perceive the ethical foundations of the organization to be upheld. Yet as collectives grow, they tend to introduce formal organizing practices that risk undermining their espoused values (Michels 1966; Piven and Cloward 1977; Osterman 2006). Over time, this process can lead to declining member participation, threatening community vitality and survival (Oakes et al. 1998; Voss et al. 2000; Weinberg 2003).

Unlike the collectives studied in extant research, however, collective social entrepreneurship initiatives are not based on just one ethical ideology. They often combine social, environmental, and economic convictions within a single initiative in order to address complex sustainability issues whose solutions require collaboration from multiple institutional spheres (George et al. 2016). As Besharov (2014) notes, sustaining member engagement is more complex when the organization in which members participate pursues multiple and seemingly competing objectives. Insights from prior research about the specific challenges involved in sustaining member participation, as well as how collectives effectively manage these challenges, may therefore be of only limited relevance for collective social entrepreneurship initiatives. Thus, while sustaining member participation is likely critical to the success of collective social entrepreneurship initiatives, neither prior research on collectivist organizations nor extant work on social entrepreneurship sheds light on the challenges involved in doing so or on the strategies through which initiatives effectively manage these challenges. In particular, it is unclear how participatory, multi-mission organizations can honor their members’ diverse ethical convictions as the collective venture develops. Our study therefore investigates the research question: How do collective social entrepreneurship initiatives engage members’ multiple value sets and sustain participation?

Method

We adopted a qualitative, inductive design suitable for advancing theory about issues not well understood in prior research (Edmondson and McManus 2007). As described below, studying German RESCoops allowed us to explore processes of collective, participatory social entrepreneurship, which have received limited empirical research attention to date. Because this setting involves a plurality of logics, it also offered an opportunity to extend prior scholarship that has focused on two institutional logics. To develop robust and transferable insights, we leveraged theoretical sampling and followed a logic of replication in our multi-case study (Yin 2003). We selected diverse RESCoop cases, using each one to test and refine insights from the others. This approach enabled us to identify common patterns and mitigate over-interpretation of case idiosyncrasies in inductive theory development. To further increase the reliability and validity of our qualitative inferences, we used various forms of data triangulation, detailed below, as well as repeated member checks with practitioners in the field (Kirk and Miller 1986).

Setting

RESCoops emerged as a new organizational population in Europe’s renewable energy (RE) sector in the early 2000s. They quickly developed into a model to organize grassroots involvement of citizens and local community organizations in the complex transition towards RE (Huybrechts and Haugh 2017). RESCoops consist primarily of private individuals of varied professional and personal backgrounds, and also frequently include institutional members such as municipalities, community banks, and local chapters of civic or environmental organizations. RESCoops bring these heterogeneous investors together to build large photovoltaic installations on roofs, green-field solar parks, wind turbines, biomass energy plants, and occasionally small hydroelectric power stations. In doing so, they pursue a tripartite mission of (1) profitably producing and selling energy, (2) using renewable sources to support environmental protection, and (3) allowing local community members to participate in and benefit from RE projects. In Germany, the setting for this study, there are over 800 existing RESCoops with more than 167,000 members. They have invested nearly two billion euros in RE projects across the country and produce enough green energy for roughly 350,000 average households annually (DGRV, 2017). Along with other actors in the nation’s RE sector, they have taken advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities created by the Renewable Energy Sources Act (Erneuerbare Energien Gesetz, EEG). First passed in 2000, the law established feed-in preference and fixed feed-in tariffs for electricity produced from renewable sources, instigating the nation’s ongoing energy transition.

Several features of RESCoops make them particularly well suited to investigate our research question. First, RESCoops are cooperatives that depend on the voluntary participation of members who pool resources and collectively govern the organization. Although members join together to invest in and operate RE projects, dependence on the organization is generally low and direct managerial control of these voluntary participants is absent. Individuals who want to support RE have multiple alternatives for doing so, such as installing solar panels on their own homes and investing in RE-focused equity funds or company bonds. In addition, following the German cooperative law (Genossenschaftsgesetz, GeG), members are free to leave at any time and receive their equity share back after a statutory grace period. Members are also not bound to the organization by any employment relationship or subject to a formal, hierarchical authority structure. In fact, the unique cooperative principle of “one person, one vote” (GeG) requires that each member has the same voting right irrespective of equity share, committing each RESCoop to democratic governance structures. Commensurately, the main governing body is the general assembly of all members. To facilitate daily operations, this assembly elects a team of leaders, i.e., directors and supervisory board members, to oversee operations between general assemblies. In most RESCoops, unpaid volunteers who are themselves RESCoop members fill these positions. Taken together, these features make RESCoops an excellent context to study collective, voluntary approaches to social entrepreneurship.

Second, as “environmental social enterprise hybrids” (Huybrechts and Mertens 2014; Huybrechts and Haugh 2017, p. 8), RESCoops espouse three distinct institutional logics—environmental (cf., De Clercq and Voronov 2011; York et al. 2016), community (cf., Schneiberg et al. 2008; Thornton et al. 2012), and commercial (cf., Pache and Santos 2013b; Thornton 2004). They thereby invoke three traditionally separate value systems and “engage in activities typically performed by three distinct organization[s] – community groups, environmental NGOs, and corporations” (Huybrechts and Haugh 2017, p. 8). As a result, RESCoops offer a rich context for understanding the challenges of sustaining member participation and strategies for addressing them, in collectives pursuing more than two distinct institutional logics. They thereby provide an opportunity to extend prior research on social entrepreneurship, which has focused on organizing efforts involving just two logics (Battilana et al. 2017).

Data Collection

From 2014 to 2015, the first author collected interview, archival, and observational data on eight RESCoops in Germany, as well as field-level data on the existing population of RESCoops. The eight purposefully sampled cases (Flick 2009) cover all areas of Germany, were founded at different points in time, and have invested in all the common forms of renewable energies in Germany. In this paper, we draw primarily on 77 semi-structured interviews with RESCoop members, 1235 pages of case-specific archival materials, and 10 hours of observation of RESCoop meetings.Footnote 1 We supplement these case data with field-level interviews and archival material. Table 1 summarizes the data we collected.

The first author interviewed 7–12 members per RESCoop, including initiative leaders as well as citizen and institutional members. We selected interviewees in order to capture the full range of perspectives in each RESCoop, asking informants to identify other informants with different opinions and/or positions than their own. Interviews were semi-structured and followed a narrative approach (Weiss 1994) in which we asked informants to report on their experiences in the RESCoop. The interview guide covered topics including personal motivation to join and expectations of the RESCoop, participation in concrete projects and in general decision-making processes, individual and organizational challenges encountered, and the reactions of RESCoop leaders. Where relevant, the interviewer further probed on contentious issues for informants and the personal compromises they made. While we allowed each conversation to develop naturally, we sought to cover the same topics with each informant, as relevant to their function within the RESCoop. Interviews with RESCoop leaders tended to be longer than those with citizen and institutional members, as directors and supervisory board members leading the organization naturally had more information to share about all aspects of RESCoop operations. Overall, interviews lasted between 30 and 150 min, with an average of roughly 50 min. Interviews were conducted in the informants’ native language of German. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. To triangulate and complement these interview data, we collected extensive archival materials on each RESCoop, including internal documents as well as publicly available data such as news articles from Factiva documenting each RESCoop’s development. In four cases, the first author also observed RESCoop member meetings during which he took extensive field notes.

In addition to collecting these case-specific data, the first author also interviewed seven field-level experts from the five regional and one national German cooperative associations. Association representatives work as founding counselors, advising RESCoop leaders as they establish an organization and often continuing to counsel them as their organizations grow. As a result, they can offer a high-level perspective on the RESCoop population in their respective areas of Germany. Our semi-structured interviews with field-level informants covered the founding process and operation of RESCoops in their region, typical challenges and best practices, legal requirements and cooperative principles upheld by the associations, as well as networking and informational activities within and across associations. To further extend our understanding of the RESCoop population and its institutional environment, we collected publications and population-level surveys from the various German cooperative associations, as well as field-level documents such as position papers on RE published by industry associations, environmental NGOs, and the Association of Municipalities.

Data Analysis

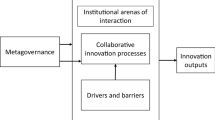

Data analysis involved three main steps, focused on understanding members’ expectations for their participation in RESCoops and the approaches RESCoops adopted to meet these expectations. First, drawing on previous scholarship and our field-level data, we developed analytical ideal types of the three institutional logics relevant to RESCoops (cf., Almandoz 2014; Smets et al. 2015). We compared guidelines for RESCoops expressed in field actors’ reports to extant ideal types of institutional logics in the literature (De Clerq and Voronov 2011; Pache and Santos 2013b; Schneiberg et al. 2008; Thornton 2004; Thornton et al. 2012; York et al. 2016), constructing field-specific incarnations of well-documented institutional logics to aid analysis in our research setting. We triangulated these ideal types with interviewees’ perceived expectations. This approach allowed us to check whether actors in the field and within RESCoops actually followed the three logics. It also led to a key insight that guided our subsequent analysis—we observed that while members agreed all three logics were important, they differed in how they prioritized the values underlying these logics. Table 2 summarizes the ideal type logics we identified.

Second, we investigated how these logics, and members’ divergent prioritizations of them, were instantiated in RESCoop decision making. To do so, we developed in-depth case histories for each RESCoop detailing projects undertaken, challenges encountered, and final decisions implemented. We found that RESCoops regularly faced trade-offs between the different prescriptions of these logics as they sought to realize concrete RE projects. If unaddressed, these trade-offs could jeopardize members’ satisfaction with the RESCoop, resulting in loss of member support and, in the extreme, threatening the RESCoop’s continued growth or even its very existence. While the extent of trade-offs varied across specific projects, they consistently occurred, challenging RESCoops to develop reliable means of handling them.

In the third and final stage of analysis, we sought to understand how RESCoop leaders managed these trade-offs and sustained members’ participation and support. As noted above, we looked for replicable patterns across cases to develop transferable theoretical insights (Yin 2003). To facilitate this cross-case analysis, we developed tables and graphs to identify common patterns in the case histories (Miles and Huberman 1994). This process surfaced three compromise strategies, each one offering a different approach to justifying project decisions that violated member’s personal value priorities and carrying different implications for organizational growth.

Findings: Generating and Sustaining Participation in Collective Social Entrepreneurship

Facing Divergent Value Priorities

RESCoop members, these heterogeneous members tended to share an ideal of pursuing community, environmental, and economic objectives concurrently. Yet, this general agreement on a triple bottom line orientation did not imply full alignment of members’ varied interests. Individual members’ divergent value priorities became apparent in concrete project decisions, as these often required making trade-offs between elements of RESCoops’ tripartite mission.

Agreement on a Triple Bottom Line

Consistent with the RESCoop field as a whole, the eight RESCoops we studied sought to combine community, environmental, and commercial concerns in a single organization and made an explicit commitment to a tripartite mission. This commitment featured prominently in RESCoops’ promotional materials and websites, as illustrated in Case 2:

The [RESCoop] aims to offer citizens of the region an opportunity to actively contribute to a sustainable and decentralized energy supply by participating in our venture… This citizen activism will directly contribute to a climate and energy future that will protect the environment for future generations, develop our region, and benefit local inhabitants by allowing them to share in value creation. [Website, Case 2]

Private citizens and local organizations who became members and invested in the RESCoops tended to agree on the desirability of this tripartite mission. In fact, this triple bottom line positioning was often what initially attracted members to RESCoops rather than other forms of investment in the RE sector. Members tended to be well versed in the three logics their organization sought to combine, valued these logics, and believed in their potential compatibility. As one member explained when discussing his expectations and reasons for joining:

We want to show that renewable energies are beyond mere eco and idealist projects, that they can also make economic sense. That is the core of the venture – you can make money with such projects and protect the environment and do something for the community. [Member, Case 3]

General agreement on the importance of a triple bottom line united members, setting RESCoops apart from large utility companies and profit-driven RE project developers. Table 3 provides additional illustrative examples of members’ commitment to a tripartite mission.

Individual Differences in Value Priorities

While RESCoop members agreed on the importance of a triple bottom line in the abstract, they differed in the relative priority they placed on each component of the tripartite mission. For example, one member described community and environmental concerns as paramount, with financial considerations as secondary:

I do want my investment not to go down in value and I expect a certain return, but two other issues are clearly in the foreground for me… the ecological ideal – that I want to try to really use the most ecologically friendly energy source – and this ideal of citizens working together to benefit our region. [Member, Case 5]

Such equitable attention to two out of the three logics influencing RESCoops was not very common in our data, however. Most members articulated a clear priority for values associated with one logic and described the others as secondary or tertiary to them personally. We describe these differences in priority orderings below and provide additional examples in Table 3.

For some members, community development through regional investment was paramount. These individual citizen members and municipalities chose to join RESCoops first and foremost to strengthen their home town and region. They expected RESCoops to support community development by sourcing locally, creating local jobs or employing local tradespeople, sharing project benefits with local residents, and increasing the welfare of their community as a whole. They thus placed primary importance on values associated with the community logic: solidarity, mutual support, and self-help. In the words of one citizen member:

There is this principle of creating jobs locally and supporting the farmers and tradespeople in our village. That is the idea of [this RESCoop], that you support the region, the people who live here, the tradespeople who offer their services here. That is what I like about it. [Member, Case 7]

In the extreme, a few interviewees who prioritized community values described financial returns as irrelevant to their participation in the RESCoop and environmental concerns as secondary:

To me it’s not about the financial [dividend]. I don’t say: ‘I want to make profit.’ It is really just this idealistic idea… to support regional activities, to strengthen the region… because I find this goal of regional energy supply important and forward-looking, ideally of course using renewable energy sources… I see the money [I invested] largely as a donation. [Member, Case 5]

Other members prioritized the environmental component of their RESCoop’s tripartite mission, seeking to contribute to climate protection, careful use of environmental resources, and an eco-friendly energy future. Environmental organizations and “green” individual members were especially interested in projects that offered green-house-gas reductions and minimal environmental impact. Frequently, this entailed critically evaluating different green energy technologies and their implementation:

I am really in it for the ecology. Considering biogas plants, I get sick… Mono-cropping on the fields… really has nothing to do with ecology anymore. That has everything to do with making money!… I am absolutely against the construction of further biogas plants. [Member, Case 5]

These members prioritized values associated with an institutional logic of environmental protection, such as the intrinsic value of nature and intergenerational justice in the use of environmental resources. Many environmentally-minded members articulated the ethical responsibility they felt towards the environment and future generations. For example:

We have to start. We simply have to start. We must not say: ‘This little bit that I emit doesn’t do any damage.’ Everything contributes. We have to think about… future generations. They also want to live in a safe environment! [Member, Case 4]

For these members, climate action and the construction of new energy supply infrastructure in the most environmentally friendly way possible were more important than maximizing annual dividends or having the biggest possible impact on regional development.

Still other members were attracted to RESCoops primarily for financial reasons, while appreciating environmental and community concerns. Local banks, for example, saw RESCoop investments as an opportunity to strengthen their local reputation and to develop business clients, as RESCoops frequently worked with these banks to finance their RE projects. For private individuals, renewable energy projects promised higher returns than conventional savings products in times of low interest rates. As one member explained:

First and foremost, it is an acceptable investment option. It yields a decent dividend… With the recent low interest rates on saving accounts, this is quite an acceptable alternative. I think they manage frugally. [Member, Case 5]

These commercially-minded members were most interested in stable returns on their investments, giving primacy to the values of return maximization and economy in operations associated with the commercial logic. Commercially minded members were thus supporters of the most cost-effective and highest yield RE projects. To realize these objectives, they were willing to place relatively less importance on community and environmental concerns.

Data from field-level sources provide further evidence for these differences in individual priority orderings. For example, when describing his daily work advising and supporting RESCoops, a cooperative association counselor explained:

Municipal representatives are always focused on the regional benefit: ‘Everything that is being realized has to benefit the region.’ For the environmental organizations, climate change and the ecological aspects naturally take center stage. And for those people who have some money, when it comes down to it, they are neither truly interested in regional benefit nor in climate change. […] When a bank, even the local cooperative bank, joins, then they definitely have an economic orientation. Money becomes very important. [Cooperative association counselor]

Similarly, survey research on RESCoops conducted in Belgium noted “significant differences in preferences and interests across categories of members,” with considerable heterogeneity in profit, environmental, and social orientations of members (Bauwens 2016, p. 287).

The Emergence of Value Tensions

Differences in members’ relative priority orderings between the values associated with community, environmental, and commercial logics became salient when RESCoops embarked on specific projects. Most projects required trade-offs between values and few could maximize all three dimensions simultaneously. As a result, any particular project undertaken was unlikely to satisfy the priority orderings of all members. When planning a biogas plant, for example, a RESCoop might choose to use local contractors and suppliers, thereby benefitting the community and speaking to values of mutual support and solidarity, but doing so could hurt profitability, reduce dividends for members, and thus violate values of return maximization and economy in operations. Decisions about what crops to use to supply a biogas plant also invoked trade-offs. While intensive, fertilizer-reliant corn cultivation offered one of the most profitable approaches, it had a considerable negative impact on local biodiversity and carbon footprint, thereby conflicting with the intrinsic value of nature, climate protection, and thus intergenerational justice.

Because members differed in their personal value priorities, tensions could emerge when such project decisions had to be made. As one director explained:

We saw tensions arising around the topic of biogas… There are many ideological disagreements that bubble up, things like… how much mono-cropping in corn, appropriate fertilizer use. So, a lot of issues where some people are saying: That’s problematic. [Leader member, Case 3]

In another case, a RESCoop supervisory board member described tensions in project location choices, particularly for green-field solar and wind turbine projects:

Not every site is equally good. Can I do it here or do I have to go outside the region a bit? What about [the cost implications of] environmental protection? Because the more I have to invest, the smaller the return. I have to conciliate that somehow. I always have in mind that we have basically promised our members not to go much below a return of 3% p.a. So we have to see how big the return will be, and how can we get that return for our members so they will stay happy, because not all of them are doing it just for the environment or regional benefit. [Leader member, Case 1]

Table 3 includes additional illustrative data on value tensions, and Table 4 offers a summary of trade-offs and associated value tensions by type of RE project.

While value tensions were evident across all types of projects that RESCoops undertook and involved varying combinations of logics, our data indicate two important patterns. First, the potential for value trade-offs differed across energy type, from relatively uncontentious solar projects to more contentious wind and biogas projects. To capture this pattern, Table 4 lists types of RE projects in order of their contentiousness. For example, given that solar installations were not very disruptive to the landscape and produced hardly any noise emissions, especially compared to wind turbines, solar location decisions tended to involve less severe trade-offs between community and commercial values than wind projects did. Also in contrast to wind turbines, solar installations did not pose a lethal threat to migrating birds and usually did not require forest clearance to be placed in high-yield locations. As a result, they generally implied smaller trade-offs between environmental and commercial values as well. This pattern of solar projects being on the lower end of contentiousness and wind and biomass on the higher end is consistent with patterns of media attention at the field level. While press coverage of solar projects was overwhelmingly positive, wind turbines and biogas plants were frequently questioned and attacked.

Second, trade-offs in this setting existed primarily between commercial and environmental values or commercial and community values, whereas very few tensions emerged between environmental and community values. As Table 4 illustrates, 11 of the 18 key project characteristics involved trade-offs between commercial and community values and six involved commercial vs. environmental values. We found no instances where community and environmental values were perceived to be at odds by RESCoop members. This does not mean, however, that these values were always synergistic, as attending to community concerns did not necessarily also address environmental concerns. For example, Case 1’s decision to place less lucrative solar roof installations in each municipality in its region heeded values of solidarity and mutual support, yet this decision did not affect environmental values, as the CO2 avoided by these installations would be the same no matter where they were realized.

Strategies for Managing Members’ Divergent Value Priorities

Managing the value tensions that emerged in project decisions was of paramount importance for RESCoops, not just for fulfilling their tripartite mission but also for retaining members. If members perceived their values to be violated or threatened, they could withdraw their contributed resources and leave the cooperative, putting the continued growth or even the very existence of the collective social enterprise at risk. To prevent such negative consequences and avoid members’ dissatisfaction with organizational decisions that did not align with their personal value priorities, the RESCoops in our study adopted three strategies, which we label temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise. Most RESCoops used one primary compromise strategy, with some also engaging a secondary strategy. We describe these strategies below, using case examples to illustrate our findings. Table 5 offers additional examples for each strategy.

Temporal Compromise

The first strategy, which we label temporal compromise, involves oscillating in value prioritization over time. When privileging one value (or set of values) in a concrete project in the present, a RESCoop engaging in temporal compromise simultaneously made credible commitments to privilege other values in the future. In this way, the RESCoop sequentially attended to each of the different value priorities important to its members.

Temporal compromise was the primary strategy adopted in Cases 1 and 2. The RESCoop in Case 1 was initiated by municipalities interested in developing the local region and contributing to their local climate protection plan. As one of the supervisory board members explained:

We want to generate the energy that we need in our own region.… Environmental protection, local patriotism, and of course value creation for our region – those three things are extremely important to us! Because we want to keep the money that our region [spends on energy consumption] in our region. [Leader member, Case 1]

To symbolically emphasize its commitment to community development, the RESCoop even chose its name to match the acronym on the local license plate. Yet while it emphasized the local community, the RESCoop attracted over 13 million euros of investments from private individuals, many of whom saw it first and foremost as an “acceptable investment alternative.” To balance its members’ divergent value priorities, this RESCoop realized a mix of projects over time. Seeking to benefit all the local municipalities involved, it undertook solar projects on public buildings in every town, but it sequentially interspersed these low-return projects with more profitable green-field photovoltaic parks. As another supervisory board member explained:

Smaller solar projects tend not to be quite as profitable, but we have decided that in each municipality we should have at least one solar installation on the roof of a public building… In larger [green-field] solar projects we therefore pay more attention to returns. [Leader member, Case 1]

To support overall portfolio returns and satisfy commercially-minded members, the RESCoop even began investing far outside the area of its member municipalities, despite its name and local commitment. In particular, it decided to invest in a large solar park that was not only outside its home county but even in a different federal state. While leaders were aware of violating the values of community benefit and support for local tradespeople and contractors, they felt compelled to undertake the project to deliver on the values of return maximization and economy in operations prioritized by those who primarily saw their membership as an investment. In recommending this project, however, leaders made sure to credibly signal to community-minded members that they would actively seek to “repatriate” the investment in the future, as soon as they could find an equally profitable project opportunity locally:

We realized [the project] outside the region in the legal structure of a Limited… The advantage is that as soon as we have a wind or solar power project ready in our region, we can simply sell [the Limited]. You can sell it more easily than having to sell a part of a cooperative… This compromise satisfied most sceptics. [Leader member, Case 1]

In summary, the temporal compromise strategy functioned by giving serial attention to different values in concrete projects, compromising members’ heterogeneous priority orderings across time. To do so, it relied on members’ trust that the RESCoop would ultimately adhere to all three sets of values, even as specific project decisions created temporary imbalances.

Structural Compromise

In the second strategy, which we label structural compromise, RESCoops offered members a choice of different projects, enabling them to select projects that fit their personal value orderings. Making use of “Nachrangdarlehen,” a specialized loan vehicle under cooperative law (GeG), members primarily invested in specific projects which they could select based on their personal value priorities, rather than placing most of their investment in the cooperative’s general equity and the entire portfolio of projects. Members with different value hierarchies were thus structurally separated and invest in different projects. In contrast to temporal compromise, prioritization therefore differed across projects rather than oscillating over time.

Cases 3 and 4 in our study relied primarily on structural compromise. In Case 3, for example, leaders compiled a detailed description for each project which clearly specified the cost and return structure, environmental impact and predicted emission reductions, as well as benefits to the local community through rents, local sourcing, and investment. Based on this information, members could decide for themselves what they wanted from a new project and what value trade-offs were acceptable to them, investing accordingly. One member explained:

A specialty of this RESCoop is that the projects are not in one big pot with a dividend that trickles out in the end. Instead, you are invested in one specific project. You can explicitly choose a project… The capitalist would say: ‘I’ll participate in the project with the biggest return.’ But one can also participate in a project that is close by – it may not have quite the best return because it doesn’t have quite as much wind or sun, but it may be much stronger on idealistic criteria [such as supporting the local community]. For example, when we put solar panels on a kindergarten, then there are of course idealistic aspects…We can support the kindergarten with cheaper electricity and also realize other idealistic goals [such as awareness raising for climate change mitigation]… I am really happy that citizens’ capital, like mine, can be used to realize such projects. [Member, Case 3]

Self-selection of members into projects reduced the burden on leaders to actively compromise members’ heterogeneous value orderings and enabled RESCoops adopting this strategy to realize a broad variety of projects. A director in Case 3 explained:

Usually, we have projects with more than three percent return, [but we also have] idealist projects. For example, for hydropower we’ll do it if it only breaks even, as long as we have members to invest in the project. That is the benefit of our system, that you can realize [commercially] weaker projects without dragging the portfolio down. If you don’t separate projects out, you would have discussions: ‘This really pays [but] you did this hydro-project and that barely breaks even.’ We don’t need to have these kinds of arguments. If we find people for projects [with a strong environmental benefit but low financial return], we do realize them. That is our principle. [Leader member, Case 3]

The structural compromise strategy thus functions by directing members’ investments to specific projects that deliver on their personal value priorities. Heterogeneous member preferences are thus more or less directly reflected in the project range of the RESCoop at any given point in time.

Collaborative Compromise

The third strategy, which we label collaborative compromise, entailed jointly developing common criteria for upholding community, environmental, and commercial values. Unlike structural compromise, collaborative compromise created organization-wide consensus about what minimum thresholds were acceptable for all three sets of values, rather than allowing individual members to choose their own individual thresholds. Unlike temporal compromise, these threshold criteria were communally agreed and relatively stable over time, rather than shifting with each new project decision.

Cases 5 through 8 adopted this strategy as their primary means of managing divergent value priorities among members. In Case 5, members included participants in local community clubs, chapters of environmental NGOs, and citizens seeking an acceptable investment, as well as the local municipal government. The RESCoop’s leaders, a community banker and a renewable energy engineer, established a culture of dialogue within the organization, routinely discussing with members the guiding principles for their organization. A supervisory board member explained:

We put this on the meeting agendas, so that everyone knows we are not just reviewing numbers but actually discussing basic principles… And we note all the wishes of the members and then vote on the [criteria], developing a basic shared understanding… Even those who may originally say ‘no’ to a project can live with it when they learn that all the [criteria] are met. [Leader member, Case 5]

Such discussions were facilitated by the cooperatives’ democratic structure and the principle of “one person, one vote.” These features allowed all members to have a voice in the collaborative search for an acceptable value consensus irrespective of their individual equity share and thereby helped resolve controversies and maintain member support. As a director in Case 5 explained:

In our cooperative each member has one vote, no matter whether he has one share or twenty. Each person has one vote and can thus influence the direction of activities in our general assembly. Last year, for example, we deliberately discussed wind power and we had a pretty diverse range of opinions. One said: ‘Anything that isn’t nuclear power is helpful.’ Another said: ‘I deliberately invested here because I do not want ugly wind mills here in our region.’ Others had more nuanced opinions, saying: ‘Okay under certain circumstances—not close to residential areas, not in the forest’… And so in the end we decided on certain criteria under which we would consider a project. [Leader member, Case 5]

Collaborative compromise thus functions by jointly and democratically creating consensus on how to uphold the collectives’ values when trade-offs occur in project decisions. It relies on members’ willingness to participate in discussions and to defer to majority decisions when necessary. It is thus focused on discovering or building value consensus among members, made concrete in explicit minimum criteria for acceptable RE project characteristics.

Towards a Comparative Framework of Compromise Strategies

Temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise each enabled RESCoops to mitigate dissatisfaction among members, even though specific project decisions did not always conform to members’ personal value priorities. As a result, all three compromise strategies served to sustain member participation. However, RESCoops drawing on different primary compromise strategies had distinct growth trajectories, reflecting differences in how each strategy enabled members to justify value concessions.

Member Participation and Growth Trajectories

In terms of their ability to maintain voluntary participation and member support in the face of value tensions, the three strategies of temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise were largely equifinal. Across cases that used different strategies, membership grew over time or remained stable, with attrition generally well under 10%. Moreover, when explicitly asked about satisfaction with their RESCoop’s activities, 76 of the 77 members we interviewed indicated general approval and no intention to leave their organization. There was also very little open conflict, despite diversity in members’ value priorities. As a cooperative association counselor explained:

To date, we have really not had any major conflicts occur… There is one RESCoop where there is some friction at the moment. There are disagreements between business and civic members of the cooperative, and this has led to veritable arguments. But that is very unusual. [Cooperative association counselor]

Yet while all three strategies were associated with sustained member participation, we found differences in organizational growth patterns. Table 6 summarizes each RESCoop’s project portfolio, membership size, and total member equity invested by the end of 2015. As Table 6 illustrates, the cases primarily relying on temporal compromise (1 and 2) grew the most in size and number of projects relative to their age. Case 1 was one of the largest RESCoops in Germany in terms of assets held as of 2015. While Case 2 was the smallest RESCoop in our sample in terms of equity, it was the fastest in its founding process, realizing three solar roof installations in quick succession. Indeed, a cooperative association counselor we interviewed identified it as one of the fastest growing start-up RESCoops in the association’s region. By comparison, cases that primarily leveraged structural compromise (3 and 4) realized or were actively pursuing projects using the most diverse set of RE sources. Case 3, for example, had realized three wind turbines, ten solar installations, and a biogas plant, and was actively investigating a hydropower station. In contrast, cases relying primarily on collaborative compromise (5 through 8) tended not to expand beyond a single project and stagnated in size, despite their age. Three of these four cases (6, 7, and 8) realized one comparatively large project primarily involving biogas, and two of these (7 and 8) satisficed with this one project given the difficulties of expanding their portfolio. Case 5 tried to realize more projects but missed an opportunity to participate in the development of a wind park due to time-intensive discussions among members about acceptable criteria for wind power investments. Facing challenges in integrating new members, Case 5 also failed to realize a biomass project.

Distinct Mechanisms for Justifying Value Concessions

The mechanisms through which temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise handle value trade-offs help explain RESCoops’ divergent growth trajectories despite convergence in terms of member retention. Specifically, the three strategies differ in how they enable members to justify value concessions—i.e., instances in which collective organizational decisions violate their personal value priorities. We explain these implications below and summarize the key dimensions of difference between compromise strategies in Table 7.

In temporal compromise, organizational decisions and activities sometimes departed from members’ personal value orderings. Members had to accept the promise of future compensatory action for a violation of their own value hierarchies in the present, justifying an organizational decision they personally would have made differently. This compromise strategy thus required individual members to license—through prospective recompense—what felt like an infringement of their personal ideals. For example, a member may accept a lower return on a community roof solar project when anticipating a compensatory higher dividend from a more profitable future green-field solar park. As an investment-minded member who primarily valued the commercial aspect of the RESCoop’s mission in Case 1 explained:

We accept… that the dividends have to be a bit lower for a while if the municipality is using it to do something for the community with it… I have heard that [the RESCoop portfolio] is a very solid [investment] nonetheless. I have just talked with the former mayor, who we know well, and I trust his word. [Member, Case 1]

Compromising ones’ value priorities could be justified by each member as only transitory. This requires, however, that the individual member continued to believe in the overall balanced orientation of the organization and trusted in promised recompense. Temporal compromise thereby defers acknowledgement of potential incompatibilities between the institutional logics espoused by the social enterprise ad infinitum. As long as the RESCoops adopting temporal compromise could credibly assure members of continued oscillation, value tensions did not have to be resolved. In consequence, these RESCoops gained flexibility for organizational growth. Perpetuating the premise of a synergistic triple bottom line, a RESCoop could relatively easily increase its investment capacity by admitting new members or allowing re-investments of extant members at any time. From this pool, leaders could invest in emerging RE project opportunities as long as they credibly signaled that future projects would attend to values not prioritized in the present.

Under a structural compromise strategy, in contrast, members encountered very little personal value compromise in the concrete projects in which they were invested. Because they had detailed information on RE project characteristics when making investment decisions, they could select projects that align well with their personal value hierarchies. For example, they could decide what level of deforestation, financial return, and local contractor involvement was acceptable to them personally. This self-selection process spared members from compromising their value priorities. Thus, structural compromise avoids acknowledgement of potential logic incompatibilities by enabling self-selection at the project level. Members did, however, have to accept that the organization as a whole had a project portfolio that only partly aligned with their personal value orderings, and be willing to overlook that or justify it as a means of enabling each member to realize his or her own ideals. As a member from Case 3 explained:

Well, I am always watching for whether it still fits or whether some [mission components] win out over others… I am not anticipating that will be the case or that I would have to withdraw my support from our RESCoop. I think this model [of everyone choosing their own project to support] is very stable… I get what I sign up for and others do too. [Member, Case 3]

As long as the RESCoop found members who subscribed to this premise, it could avoid value tensions in project decisions and gain flexibility in project range, as any project with sufficient investors could be realized. This project-bound investment model could also slow growth, however, because projects had to be clearly specified before investments could be solicited, and they could only be realized if a sufficient number of like-minded members came together to fund them.

In collaborative compromise, leaders engaged members in a consensus-building or democratic voting process to establish value concessions acceptable to all or at least the majority of members. This approach allowed members to learn more about RE projects and reflect on, as well as possibly adapt, their own personal value orderings. In a discussion of biogas, for example, an agreement to limit the use of corn could address the concerns of environmentally-minded members who might otherwise oppose biogas projects due to the negative environmental effect of monocropping. Collaborative compromise thus required that members were willing to invest time in discussion, and in the end, they had to accept the outcome of a democratic vote that may not have matched what they would have personally decided. For example, when asked what he would do if the general assembly were to decide on a criterion he did not personally support, a cooperative member in Case 5 responded:

What would happen? I could not oppose it in the cooperative anymore. That is simply a democratic principle, that I don’t petulantly say: ‘Okay, that’s it, I am leaving!’… Instead, I’ll stay in the cooperative. [The decision] is legitimate. So I’ll say: ‘I am still opposed, but okay.’ And I will just try to continue to convince others that the criterion is nonsense. [Member, Case 5].

To justify compromising their personal value priorities in such joint decision-making processes, members diffused ethical responsibility to the group, thereby rendering value concessions more acceptable to them personally. Collaborative compromise thus entails explicitly acknowledging the potential for incompatibilities between the logics espoused by the RESCoop and jointly, in dialogue and through democratic decision-making, finding acceptable truces. If the RESCoop succeeded in developing a culture of active debate focused on collaborative problem solving, value tensions could be satisfactorily resolved for those involved in the process. Yet incorporating new members was increasingly difficult, as newcomers had to subscribe to the organization’s established value consensus and minimum project criteria. This in turn limited the ability to grow through new investments. The process also entailed potentially long discussions and extended decision-making processes, making it more difficult to realize growth.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although social entrepreneurship frequently involves collective, voluntary organizing efforts little research to date has examined the challenges involved in such initiatives or strategies for managing them. Our comparative, qualitative, inductive analysis of eight renewable energy cooperatives in Germany identified sustaining participation in the face of members’ heterogeneous value orderings as a key challenge in these collective social ventures. As voluntary participants can easily withdraw from an organization, maintaining their satisfaction is paramount for sustained participation. While members were initially attracted to the initiatives we studied due to their positioning as triple bottom line businesses and agreed on the importance of multiple missions in the abstract, they frequently disagreed on the relative priority that should be given to each mission component in concrete projects. To sustain members’ satisfaction with, support for, and participation in the collective social enterprise, RESCoops therefore had to convince participants to accept decisions that may violate their personal value priorities. We found three strategies for doing so—temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise—and uncovered the divergent implications of these strategies for organizational growth. Our findings make several contributions to research on social entrepreneurship and hybrid organizing, and in doing so highlight the importance of values for institutional theorizing (cf., Kraatz et al. 2010; Kraatz 2015; Vaccaro and Palazzo 2015) and the generative potential of an ethics perspective.

First, we offer new insight into the nature of the challenge involved in engaging multiple value sets and sustaining participation in collective social entrepreneurship by calling attention to the role of individuals’ heterogeneous value orderings. Previous research on employment-based social enterprises has emphasized challenges arising from internal sub-groups disagreeing on the appropriate mission of their organization (Battilana and Lee 2014; Ashforth and Reingen 2014). In these studies, controversies and conflict arise as a single organization seeks to bring together employees from different professions who carry their respective value systems into the organization (Almandoz 2014; Glynn 2000; Pache and Santos 2010, 2013a). In daily interaction, fault-lines emerge as employees’ values clash (Battilana et al. 2015; Reay and Hinings 2009; Battilana and Dorado 2010). Although a few studies describe organizational members who serve as carriers of multiple logics simultaneously, this work assumes members agree on the relative priority of logics, often implying they prioritize two logics equally (e.g., Smets et al. 2015).

In contrast, in the collective, voluntary social entrepreneurship initiatives we studied, individuals agreed on the desirability of combining multiple institutional logics, yet they disagreed on the relative prioritization of logics and their associated values. Differences in priority orderings are consequential, because organizational decisions frequently require trade-offs between different values. Effectively managing these trade-offs can help collective social entrepreneurship initiatives satisfy members’ diverse ethical ideals and thereby sustain member support and engagement. In highlighting this issue, our study broadens existing understandings of the challenges involved in social entrepreneurship and calls for scholars to consider not just tensions between carriers of different logics, but also tensions that emerge when members accept multiple logics yet disagree on their relative importance. This issue may be particularly important when initiatives combine three or more logics, as the possibility for differences in priority orderings is greater than in dualistic contexts.

Second, we offer new insight into the management of hybridity and multiple logics by showing how strategies uncovered in past research address a broader set of challenges than previously recognized and by unpacking the mechanisms through which they do so. Our findings and theorizing about how temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise enable alternative ethical justification processes suggest that hybrid organizing strategies not only sustain divergent organization-level priorities (Battilana and Dorado 2010; Smith and Besharov, forthcoming) and appease competing institutional demands (Pache and Santos 2010, 2013), but can also ensure the ongoing participation and retention of members without recourse to employment-based managerial practices and authority structures. Whereas much prior research has focused on why particular institutional demands are given priority, we unpack how the “losing” demands in organizational logic prioritization can be satisfactorily managed (Greenwood et al. 2011, p. 351), thereby extending understanding of the scope of hybrid organizing strategies.

In particular, past research has found that strategies of oscillating between competing demands or logics in a manner similar to the temporal compromise strategy we uncovered can enable formal employment organizations to uphold dual logics or competing demands over time (e.g., Smith and Besharov, forthcoming; Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009). Our study expands this research by showing how a strategy of shifting priorities over time serves to accommodate members’ individual value priorities and sustain their participation, as it enables members to rationalize value transgressions as only transitory. By deferring recognition of the potential incompatibility of different values that the collective social enterprise embraces, not only does temporal compromise sustain multiple missions over time at the organizational level (the focus of prior work), but it can also mitigate estrangement at the individual level and maintain satisfaction of those having to accept (transient) violations of their personal values.

Prior research has also described structural separation of multiple logics, for example relegating them to separate organizational sub-units through compartmentalization (Binder 2007), as a strategy for mitigating conflict between groups of employees (Greenwood et al. 2011; Pratt and Foreman 2000) and as a means of ensuring both logics receive dedicated attention and focus on an organizational level (Ebrahim et al. 2014; Tushman and O’Reilly 1996). Our findings add to this work by showing how strategies that structurally separate organizational components prioritizing different logics also support member satisfaction and participation. By enabling individuals to affiliate with the organizational component (in our case, an RE project) that best meets their personal value priorities, structural compromise allows individual members to realize their ethical ideals and thereby helps sustain their engagement. Notably, we find that this strategy does not necessarily require focusing on a single logic in a given organizational subunit, as in compartmentalization (e.g., Binder 2007). Instead, in the context of members’ general agreement on a multiplex mission, practices that structurally separate different logic hierarchies from one another are sufficient.

Past studies have also shown that opportunities for collaboration and negotiation facilitate the emergence of compromise and prevent conflict between employees aligned with competing logics (Battilana et al. 2015; Ramus et al. 2016). Our findings on the collaborative compromise strategy used by RESCoops extend this work by highlighting the value to individual members of making collaborative decisions. That is, we show that collaborative compromise can not only prevent intergroup conflict or mission drift on an organizational level but can also enable individual members to justify violations to their personal value priorities. As decisions are taken jointly, individual members can diffuse responsibility for accepting value concessions to the collective. Furthermore, as collaborative compromise involves considerable discussion, individual members have an opportunity to learn about others’ value priorities and to revisit their own positions. Estrangement among members of the collective is thus mitigated and even members whose personal priorities may differ from the collective’s decision remain engaged.

Third, whereas prior research on social entrepreneurship and hybrid organizing has tended to focus on settings involving just two logics and to treat them as contradictory (Battilana et al. 2017; Greenwood et al. 2011), by studying initiatives involving more than two logics we reveal an important characteristic of higher-order pluralistic institutional contexts: logic combinability, which we define as the extent to which the elements of two or more logics converge and can be jointly pursued by the same activity or practice. Even when logics and their associated values are not at odds with one another in a concrete setting, they are not necessarily synergistic in that their demands may not be combinable. While proponents of each logic may be unlikely to quarrel with one another, they also may have no reason to collaborate. Because their demands do not overlap, they may not join forces in opposing a third incompatible logic, instead taking issue with different features of the third logic.

In our study, for example, only two of the three binary relationships between logics were contentious. Commercial and environmental values as well as commercial and community values were often at odds in concrete project decisions, whereas environmental and community values rarely conflicted. This situation enabled RESCoops as collective, participatory social enterprises to bring together a wide range of individual members without multiplying the potential for tensions. At the same time, the values underlying the environmental and community logics did not map onto one another. As a result, although the presence of environmentally-minded and community-focused members did not in itself create incompatibilities, it also did not reduce the range of issues to be considered, as each logic clashed with the third commercial logic on different issues. Tensions between commercial and environmental values were therefore added to the tensions between commercial and community values. Moreover, while environmentally-minded and community-focused members in our setting did not quarrel with one another, they also did not work together to collectively face the demands made by members prioritizing the commercial logic. Logic compatibility without logic combinability thus did not lead to the emergence of a combined community-environmental faction.

These findings contribute to ongoing research on the opportunities and challenges of institutional pluralism (Battilana et al. 2017; Kraatz and Block 2008; Ocasio and Radoynovska 2016; Seo and Creed 2002) by suggesting that while logic compatibility may be valuable for realizing opportunities amidst institutional plurality, logic combinability may be required to mitigate many of the accompanying challenges. Our insights also have implications for research on conflict in hybrids (Ashforth and Reingen 2014; Battilana and Dorado 2010; Glynn 2000), highlighting the analytical leverage of logic combinability, not just compatibility and centrality (Besharov and Smith 2014), in settings involving more than two logics. Because logic combinability influences the incentives for distinct factions to work with one another, it may help explain differential tendencies for collusion among some groups versus others in hybrid organizational contexts.

Limitations and Future Research

Our focus in this study was on understanding the challenges facing collective, voluntary social entrepreneurship initiatives and strategies through which organizations manage these challenges to sustain member participation. To do so, we studied eight cases that differed in age, size, location, and energy sources used. This approach enabled us to compare different strategies and their implications for enabling ethical trade-offs and organizational growth. Because the theoretical insights developed through this research derive from an inductive study of a single setting, their transferability and potential boundary conditions of course need to be considered. For example, the concrete form of temporal, structural, and collaborative compromise in our study was likely influenced by the German cooperative law and RE industry context. As the foregoing discussion has illustrated, however, these compromise strategies in their gestalt resemble more general hybrid organizing strategies. As a result, our insights into the potential of such strategies to mitigate individuals’ dissatisfaction stemming from value concessions may be transferable to other empirical settings and national contexts. In addition, while the collective, voluntary nature of the social enterprise initiatives we studied made members’ value tensions and organizational participation especially salient, other hybrid contexts are likely to face similar challenges. We expect our insights to be of particular relevance in settings such as participatory membership organizations pursuing double or triple bottom lines, as well as cross-sector alliances and public–private partnerships. We also encourage future research to explore how our insights may transfer to more traditional employment organizations, which often face competing institutional demands that lack a clear, agreed-upon priority ordering.

In addition, because the organizations we studied differed along multiple dimensions and we did not follow their development in real time, future research is needed to address the antecedents of the strategies we uncovered and their development over time. Our data offer suggestive evidence for factors at multiple levels of analysis. At the organizational level, initiative leaders and their approach to the cooperative legal form may be particularly important. The founders of Case 5, for example, were drawn to the cooperative form because of its democratic principles. Commensurately, they developed a culture of joint discussion and leveraged collaborative compromise when value tensions started to surface among their organization’s members. In contrast, the leaders of Case 4 were drawn to the cooperative legal form because the specialized loan vehicle of a “Nachrangdarlehen” allowed for some separation of project ownership within a single organization. Consistent with this orientation, their RESCoop relied on structural compromise from the start. At the field level, cooperative association counselors may play an important role, as their central position in the network of existing and nascent RESCoops allows them to contribute to cross-organizational learning and the diffusion of best practices. For example, counselors’ recommendations to involve mayors and other local officials may support the emergence of a temporal compromise strategy, because members may be more likely to accept value concessions in the present and promises for compensatory action in the future when these commitments come from trusted authority figures. Longitudinal and large N studies can further explore how these and other factors may jointly influence strategy choices.

Another area for future research concerns dynamics over time. In particular, future work can build on our findings about the implications of different strategies by exploring how organizations evolve in their use of strategies as they grow and develop. For example, studies can consider how organizations adopting a collaborative compromise approach can expand in scale, and whether doing so requires switching to a different strategy. Relatedly, research can also examine how collective social enterprises move from one compromise strategy to another. There was suggestive evidence in our data that as RESCoops adopt new types of energy sources, particularly sources that are more contentious, their legacy compromise strategy may not be sufficient. In these situations, leaders may experiment with other strategies or reach out to cooperative association counselors for best practice advice, ultimately adopting a secondary compromise strategy. For example, when Case 3 began exploring an opportunity to realize a biogas project, members voiced concerns even though they had previously accepted that the RESCoop would undertake solar and wind projects side by side through a structural compromise strategy. To appease members’ demands for a broader discussion of this new energy source, leaders adopted collaborative compromise as a secondary strategy. Single-case studies drawing on observational data and following collective social entrepreneurship initiatives as they develop can further unpack the dynamics of compromise strategies over time.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study contributes to research on collective forms of social entrepreneurship in pluralistic institutional environments by revealing novel challenges facing these voluntary initiatives and unpacking the mechanisms through which hybrid organizing strategies can be used to manage them. We hope our work will inspire future studies to attend to this increasingly common and important form of hybrid organizing, helping collective social enterprises live up to their full potential in addressing critical societal problems.

Notes

In the findings description, we refer to “Leader members” and “Members” to distinguish between informants elected into leadership positions within their RESCoops and other members.

Abbreviations

- EEG:

-

Erneuerbare Energien Gesetz (Renewable Energy Sources Act)

- GeG:

-

Genossenschaftsgesetz (Cooperative Law)

- RE:

-

Renewable Energy

- RESCoop:

-

Renewable Energy Source Cooperative

References

Adler, P. S. (2001). Market, hierarchy, and trust: The knowledge economy and the future of capitalism. Organization Science, 12(2), 215–234.

Almandoz, J. (2014). Founding teams as carriers of competing logics: When institutional forces predict banks’ risk exposure. Administrative Science Quarterly, 59(3), 442–447.

Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20(4), 696–717.