Abstract

Enforcement of new—or relatively new—administrative powers targeting control and criminalization of behaviorbehavior has become increasingly common in Italian cities in recent years. Defined as ordinanze sindacali, Mayors’ Administrative Orders (MAOs) have traditionally been among the powers available to mayors to regulate urban life. Under a new national law passed in 2008, their use in controlling undesirable behavior ranging from minor social and physical incivilities to prostitution and social problems like begging and vagrancy has become increasingly common. In this paper, using data from our own research and from national and local studies, we discuss these orders from a new perspective, showing how they have been used in Italy to criminalize statuses and behaviors of a specific vulnerable social group: namely, legal and illegal immigrants. We describe the main features of these administrative tools, their complex interactions with the criminal justice system and immigration laws, and the mechanisms through which they target irregular and regular immigrants and their use of public space. We contextualize their enforcement in Italian cities in the broader development of exclusionary policies against immigrants and in the more general tendency to increase criminalization of groups and behaviors that seem to be part of a common punitive turn in many Western countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This issue raises the question about the possibility that MAOs may also play a “decriminalization” role in transforming minor criminal offences in administrative violations, mostly sanctioned through administrative fines instead with criminal punishment. However, this “decriminalizing” effect of MAOs is not confirmed by our research, since MAOs are addressed at sanctioning behaviors that the criminal justice system cannot deal with. Thus, without the enforcement of MAOs, these behaviors will mostly go unnoticed and not sanctioned.

It is not merely coincidence that the Minister of the Interior who re-envisioned MAOs in “Zero tolerance” style in 2008, Roberto Maroni, was a member of the Northern League.

Both because they have been a lengthy and stable presence in Italy and because many of them (those coming from Romania and Bulgaria) are now European citizens.

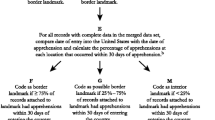

These studies together analyze the content of 780 administrative orders issued nationwide between August 2008 and March 2009 and other 500 issued between 2009–2010. This database, although not updated, is the most comprehensive available in Italy on MAOs.

After 2010, there are no available national systematic databases of MAOs. Our recent classification, which includes roughly 250 orders but is still in progress, started with analysis of local news media and then explored Italian municipalities’ websites. Our database mainly focused on MAOs that in some way involve immigrants. For the last 5 years, information is more fragmented, and the number of orders we gathered underestimates their use.

Both the Law n. 125/2008 and the following Law n. 94/2009 contain more new repressive rules generally and particularly against immigrants (Rossi 2010; Renoldi and Savio 2008; Zorzella (2008). These laws established, for instance, many restrictions for immigrant entry and legal stay in the country, introduced the aggravating circumstance of being unlawful (clandestinità), and increased the penalties for street and drug-related crimes.

“A public good to protect through activities aimed at defending, inside local communities, the improvement of civic rules, in order to ameliorate the conditions of life in the urban centre and also to strengthen civic coexistence and social cohesion”.(D.M. 05/08/2008).

As Katherine Beckett and Steve Herbert (2010, 9) wrote about American orders and civility laws: “They mobilize the civil power of injunction to address what is typically thought of as a crime problem”. Similarly, Squires (2008, 11) defined Antisocial Behavior Orders (ASBOs) as: “Hybrid new orders and quasi criminal controls with their shifting register of prevention, discipline and support”.

Art. 650 of the Italian Penal Code punishes “noncompliance with orders issued by any public authority for reasons of justice, public safety, public order or hygiene (…) with imprisonment to three months or a fine up to 206 Euros”. There seems to be a two-step process: first, the violation of the order implies an administrative fine; then, for those who cannot or do not want to comply with the administrative fine, criminal punishment may be invoked. However, some orders mention the applicability of art. 650 as a first step. MAOs differ on this point, and courts have taken different positions in deciding about the possibility of a criminal sanction at a first or even second step (Ruga Riva 2010; Giovannetti 2012). The studies available show that the criminal rule is rarely enforced (Crocitti 2010; Cittalia-Anci 2012, 54).

Not differently from the case of dispersal orders whose significance “derives in large part from the symbolic message and communicative properties they express, as much from their instrumental capacity to regulate behavior” (Crawford 2008, 755).

As with the order issued in Varese (n.20/2008): “It is forbidden to beg everywhere in the municipal area, and in all forms”.

Roma people are one of the largest European minority groups. In Italy, there is a small percentage of Roma and Sinti people (about 140,000, 0.25 % of the whole population), a vast majority of whom live in conditions of extreme poverty and about 40,000 of whom live in camps, both authorized and illegal (Associazione 21 luglio 2014).

In recent decades, camps have become urban ghettos “without the minimum requisites for human health, dignity and physical integrity” (Strati 2011, 3).

The phrasing of these orders is characterized by the use of obsolete and moralistic words that are meant to convey a message to citizens about what is proper sexual conduct. The same features of “moral authoritarianism” that characterize these regulationss, and the gendered dimension of antiprostitutions regulations, has been incisively discussed by Sanders (2009, 519) in the UK.

As the order issued in Parma (n.4442/2009) states: “a regular conduct of life in private affects and influences the broader feeling of civic coexistence in public space.” Furthermore, “phenomena of deterioration inside individual private properties create the conditions for the decline of urban quality of the whole neighbourhood.”

In Italy, non-EU citizens, once having achieved a regular permit for staying in the country, still need to prove that they have a place in which to live as a condition to be registered in the anagrafe of the municipality. This step is significant because it is through municipal residence that citizens are entitled to health care assistance and other services provided by the local governments.

These cases are documented by the media; see, for example, “Il Sole 24ore”, 08/03/2010. Many of these MAOs and administrative acts have been invalidated by administrative or civil courts for discrimination.

There are no examples of “anti-burqa” orders in the archive of Anci-Cittalia and the only information is available in some scientific articles that discuss them on legal grounds (Ruga Riva 2008; Lorenzetti 2010) in the media, and in the websites of NGOs. showing that a total of about ten of these orders were issued between 2004 and 2015.

As with the “anti-C” orders, the texts of these orders are not included in the Anci-Cittalia archive and are not available on the websites of the municipalities. Lorenzetti (2010) refers to 32 orders issued between 2009 and 2010 by mayors of a variety of small and bigger cities.

Another important group of MAOs (40 % according to Cittalia-Anci 2012, 52) addresses alcohol sales and consumption in the public space. This is the only category of MAOs that regulate behaviors not extensively performed by immigrants; young Italians are mostly involved, at least as consumers. There are, of course, also some street sex workers and beggars who are not immigrants, but they are a minority.

References

Aa.Vv. (2010), Special issue of the journal “Le Regioni”, XXXVIII, no 1–2.

Associazione 21 luglio (2014), Rapporto Annuale 2014. http://www.21luglio.org. Accessed 10 March 2016.

Beckett, K., & Herbert, S. (2010). Banished. The New social control in urban america. Oxford: OUP.

Bonetti, P. (2010). Considerazioni conclusive circa le ordinanze dei sindaci in materia di sicurezza urbana: profili costituzionali e prospettive. Le Regioni, XXXVIII(1–2), 429–450.

Bucerius, S., & Tonry, M. (2014) Ed., The Oxford Handbook of Ethnicity, Crime, and Immigration. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burney, E. (2005) Making People Behave. Anti-Social Behaviour, Politics and Policy. Willan: Cullompton.

Busatta, L. (2010). Le ordinanze fiorentine contro i lavavetri. Le Regioni, XXXVIII(1–2), 367–383.

Caputo, A. (2007), Irregolari, criminali, nemici. Note sul “diritto speciale” dei migranti. Studi sulla questione criminale, (II-1), 45–63.

Caruso, C. (2010). Da Nottingham a La Mancha: l’odissea dei sindaci nell’arcipelago dei diritti costituzionali. Le Regioni, XXXVIII(1–2), 15–31.

Catanzaro, R., Nelken, D., & Belotti, V. (1997), Luoghi di svago, luoghi di mercato, Quaderni di Città Sicure, n.16, Regione Emilia Romagna.

Chiodini, L. (2009). Le ordinanze comunali a contrasto dell’insicurezza urbana: un’indagine nazionale. Autonomie Locali e Servizi Sociali, 3, 499–510.

Cittalia-Anci (2009), Oltre le ordinanze. I sindaci e la sicurezza urbana, Roma.

Cittalia-Anci (2012), Per una città sicura. Dalle ordinanze agli strumenti di pianificazionee regolamentazione della convivenza cittadina, Roma.

Cohen, S. (1979). The punitive city: Notes on the dispersal of social control. Contemporary Crises, 3(4), 341–363.

Corda, A. (2016), Sentencing and Penal Policies in Italy: The tale of a Troubled Country. Crime&Justice. A Review of Research, 45, forthcoming.

Crawford, A. (2008). Dispersal powers and the symbolic role of anti-social behaviour legislation. The Modern Law Review, 71(5), 753–784.

Crawford, A. (2009). Governing through anti-social behavior. Regulatory challenges to criminal justice. British Journal of Criminology, 49, 810–831.

Crocitti, S. (2010), Più sicurezza in città? Il “nuovo” potere di ordinanza dei sindaci - Research Report, Regione Emilia-Romagna, unpublished.

Crocitti, S. (2014). Immigration, crime and criminalization in Italy. In S. Bucerius & M. Tonry (Eds.), The oxford handbook of ethnicity, crime, and immigration. New York: Oxford University Press.

Edsall, T., & Edsall, M. (1991). Chain reaction: the impact of race, rights, and taxes on american politics. New York: Norton.

Galantino, M. G. (2012). Domanda si sicurezza e ordinanze dei sindaci: il ruolo dei cittadini. In A. Galdi & P. Franco (Eds.), I sindaci e la sicurezza urbana (pp. pp. 81–pp. 113). Roma: Donzelli.

Gargiulo, E. (2013), Le politiche di residenza in Italia: inclusione ed esclusione nelle nuove cittadinanze locali. In Rossi, E., Biondi Dal Monte, F., & Vrenna M. (Eds), La governance dell’immigrazione. Diritti, politiche e competenze (pp. 135–167). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Gargiulo, E. (2014). Produzione di sicurezza a mezzo di insicurezza. Il controllo locale della residenza tra retoriche sicuritarie e opacità decisionali. Studi sulla questione criminale, XVI(1), 41–62.

Giovannetti, M. (2012). Le ordinanze dei sindaci in materia di sicurezza urbana e l’impatto sui territori. In A. Galdi & F. Pizzetti (Eds.), I sindaci e la sicurezza urbana (pp. pp. 27–pp. 80). Rom: Donzelli.

Giovannetti, M., & Zorzella, N. (2010). Lontano dallo sguardo, lontano dal cuore delle città: la prostituzione di strada e le ordinanze dei sindaci. Mondi Migranti, 1, 47–82.

Giupponi, T. F. (2010) (Ed), Politiche della sicurezza e autonomie locali, Bologna: Bononia University Press.

Lorenzetti, A. (2010). Il divieto di indossare burqa e burqini Che genere di ordinanze? Le Regioni, XXXVIII(1–2), 349–365.

Lorenzetti, A. (2011), Discriminazioni razziali ed etniche nelle ordinanze dei Sindaci e negli ordinamenti municipali. In Tega, D. (Ed), Le discriminazioni razziali ed etniche. Profili giuridici di tutela (pp.205–218), Roma: UNAR, Armando Editore.

Lugli, D., & Crocitti, S. (2013), Verso il superamento dei campi nomadi. Analisi e proposte per una nuova legge regionale, Quaderni della Difesa Civica - Difensore civico Regione Emilia-Romagna, n.4.

Malucelli, L., & Martini, R. (2002), I sindaci e le ordinanze. Azioni amministrative contro la prostituzione di strada, Research report, Regione Emilia Romagna, unpublished.

Maneri, M. (2013). Si fa presto a dire “sicurezza”. Analisi di un oggetto culturale. Etnografia e ricerca qualitativa, 2, 283–290.

Mazzarella, M., & Stradella, E. (2010). Le ordinanze sindacali per la sicurezza urbana in materia di prostituzione. Le Regioni, XXXVIII(1–2), 237–276.

Melossi, D. (2007). La criminalizzazione dei migranti: un’introduzione. Studi sulla questione criminale, II(1), 7–12.

Melossi, D. (2015). Crime, punishment and migration. UK: Sage.

Melossi, D., & Selmini, R. (2009). Modernisation of institutions of social and penal control in Europe: the ‘New’ crime prevention. In A. Crawford (Ed.), Crime prevention policies in comparative perspective (pp. 153–176). Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Ministero dell’Interno (2007), Relazione sulle attività svolte, Osservatorio sulla prostituzione e sui fenomeni delittuosi ad essa connessi, Roma.

Nicodemi, F., & Bonetti, P. (2009), La prostituzione straniera. http://www.asgi.com. Accessed 29 september 2015.

Pajno, A. (2010). La sicurezza urbana. Rimini: Maggioli.

Palidda, S. (2011). Il discorso ambiguo sulle migrazioni. Messina: Mesogea.

Renoldi, C., & Savio, G. (2008). Legge 125/2008: ricadute delle misure a tutela della sicurezza pubblica sulla condizione giuridica dei migranti. Diritto Immigrazione e Cittadinanza, 3–4, 24–43.

Rossi, S. (2010). Note a margine delle ordinanze sindacali in materia di mendicità. Le Regioni, XXXVIII(1–2), 277–297.

Ruga Riva, C. (2008), Il lavavetri, la donna col burqa e il Sindaco. Prove ateniche di «diritto penale municipale». Rivista italiana di diritto e procedura penale, 133–148.

Ruga Riva, C. (2010). Diritto penale e ordinanze sindacali. Più sanzioni per tutti, anche penali? Le Regioni, XXXVIII(1–2), 385–396.

Ruga Riva, C. (2012), Diritto penale, regioni e territorio. Tecniche, funzioni e limiti, Milano: Giuffrè.

Sanders, T. (2009). Controlling the ‘anti-sexual’ city: Sexual citizenship and the disciplining of female street workers. Criminology&Criminal Justice, 9(4), 507–525.

Selmini, R. (2013), Le ordinanze sindacali in materia di sicurezza: una storia lunga, e non solo italiana. In Benvenuti, S. et al. (Eds.), Sicurezza pubblica e sicurezza urbana. Il limite del potere di ordinanza dei sindaci stabilito dalla Corte costituzionale (pp.152–165). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Selmini, R. (2016), Urban Policing in Italy: Some Reflections in a Comparative Perspective. In A. Edwards, E.Devroe, P. Ponsaers (eds), Policing European Metropolises. London: Routledge, forthcoming.

Simester, A. P., & von Hirsch, A. (2006). Regulating offensive conduct through Two-step prohibitions”. In A. P. Simester & A. von Hirsh (Eds.), Incivilities: regulating offensive conduct (pp. 173–194). Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Simoni, A. (2007), Lavavetri, Rom, stato di diritto ed altri fastidi, http://www.altrodiritto.unifi.it/document/simoni.htm. Accessed 29 September 2015.

Squires, P. (2008) (Ed), ASBO Nation. The Criminalization of Nuisance, Bristol: Polity Press.

Strati, F. (2011), Promoting Social Inclusion of Roma. A Study of National Policies. http://www.peer-review-social-inclusion.eu. Accessed 19 August 2015.

Tonry, M. (1995). Malign neglect. New York: Oxford University Press.

Unità di strada (2009), Ordinanze anti-prostituzione. Rapporto di monitoraggio.

Vitale, T. (2009), Sociologia dei conflitti locali contro i rom e i sinti in Italia:pluralita’ di contesti e varieta’ di policy instruments. Jura gentium. Journal of Philosophy of International Law and Global Politics, 9 (1).

Wacquant, L. (2009), Punishing the poor. The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity, Duke University Press

Zorzella, N. (2008). I nuovi poteri dei sindaci nel “pacchetto sicurezza” e la loro ricaduta sugli stranieri. Diritto, Immigrazione, Cittadinanza, X(3–4), 57–73.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crocitti, S., Selmini, R. Controlling Immigrants: The Latent Function of Italian Administrative Orders. Eur J Crim Policy Res 23, 99–114 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-016-9311-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-016-9311-4