Abstract

Safety perceptions of residents are often analysed through surveys and compared with factual crime developments. Using the Dutch city of Rotterdam as an urban context of improved crime levels, this article provides a critique on standardised surveys in the research of safety perceptions and its presupposed connection to factual crime. Contrasting survey results from the Rotterdam Safety Index with qualitative data from 64 in-depth interviews in four districts, the qualitative narrative contradicts findings from the survey and implies more nuanced and diversified policy responses to safety issues. Because of the tendency of surveys to connect safety perceptions to factual crime, their unsuitability to catch subtle perceptions and their inability to expose new viewpoints, we argue for de-quantification: a lesser dependency on—but not a repeal of—survey data in this area, supplemented by a periodic qualitative approach in the research of crime and safety information (qualitative monitoring).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crime and safety policy today is dominated by a formal, positivistic vision. In the era of New Public Management and Big Data, because of their objective appearance, ‘factual’ figures about crime and safety are perceived as the most convincing way of communicating about social problems (Williams et al. 2016; Joh 2014; Noordegraaf 2008). Most Western cities vigorously gather numerical data on registered crime developments, perceptions of safety and the quality of life (QoL) in neighbourhoods (McCue 2014; Farrall et al. 2009; Rapley 2003). Regarding information about residents’ perceptions of crime and feelings about safety, questionnaires are the preferred tool of research. Cities are keen on statistical information in the analysis of how residents perceive the state of crime in their neighbourhood and how they value policy responses to it. Moreover, the subjective safety perceptions of residents are often measured and analysed alongside factual crime developments, treating both flows of information as two sides of the same coin. When it comes to crime and safety perceptions, policy makers and administrators are often ‘seeing like a survey’ (Law 2009).

Yet designing policy on the basis of survey information is not as straightforward as it may seem. Survey instruments are watermarked with the language, thought patterns, experiences and expectations of their designers’ cultural world (Rodríguez et al. 2015). This creates challenges when using surveys for policy information, most notably in the translation of outcomes. But it also poses more subtle challenges deriving from potentially hidden local variations in social experience. Surveys on crime and safety perceptions in particular are vulnerable to bias and misinterpretation. Research and policy more often focus on unsafe situations than on safe ones. Security is often the cause of (policy) research but may result in a construction of the research question in terms of insecurity (Bruinsma and Bernasco 2004). This also shapes the construction of survey questions in safety monitors and subsequently how residents fill out questionnaires. There is a risk of self-selection, whereby residents who are already more negative about safety issues are the most likely to participate, resulting in the silent majority being underrepresented. From the field of psychology, we also know that cognitive and communicative aspects of survey measurement are not without problems (Kahneman 2011; Ajzen and Krebs 1994; Schwarz et al. 1994). Questions such as: ‘How safe do you generally feel in your neighbourhood?’ or ‘How would you assess the crime level in your neighbourhood?’ are not as simple as ‘What is your telephone number?’ or ‘What did you have for breakfast this morning?’ Respondents to a survey topic first need to retrieve some cognitive representation of it. The more abstract the topic, the higher the risk for mental fallacies on the part of the respondent, such as question substitution or willingness to report an opinion on issues about which he or she knows little, resulting in misleading or inadequate answers (Erikson et al. 1988; Bishop et al. 1986; Schuman and Presser 1981).

Policy makers also overestimate the link between safety perceptions of residents as reported in municipal questionnaires and factual crime statistics of a neighbourhood or city (cf. Eysink-Smeets et al. 2010; Duffy et al. 2008; Farrall et al. 2000). Of course, crime rates influence social safety, but the individual characteristics of residents and the social and physical characteristics of the environment in which they live also play a role (Maas et al. 2009; Wood et al. 2008; Austin et al. 2002). Biographical characteristics affect perceptions of safety as well (Tulloch 2000; Ferraro 1995). This can be the case, for instance, when a person has been the victim of a crime or has undergone a major negative life event. Feelings of risk and vulnerability are thus not only related to an actual situation but also to how people experience and interpret that situation. In sociological terms, the (expected) risk of victimisation of crime and disorder is symbolically ‘mediated’ (Sparks et al. 2001; Ditton et al. 1999; Altheide 1997). That mediation, in turn, is shaped by what is communicated about crime and victimisation in the media or by neighbours (Kleinhans and Bolt 2013; Romer et al. 2003), like the impact of neighbourhood gossip, crime television programmes, social media, government reports on crime or social sentiment in today’s risk society (Lee and Farrall 2009; Bauman 2001; Furedi 1997; Beck 1992). In other words, factual crime developments and perceptions of safety do not form a perfect correlation.

In this article, we probe issues concerning research of safety perceptions in urban neighbourhoods and further review its policy response. Though critique on the dependence of statistics in crime research is not new, this critique is mostly limited to academic debates on theory use and methodology (see Miller and Palacios 2015; Ferrell 2009), and is traditionally geared towards victimisation studies (DeKeseredy and Schwartz 2003; Von Hofer 2000; Ullman 1997; Stanko 1995). The validity of survey instruments as a source of information for criminal policy is less explored. Using the city of Rotterdam—the second-most populous city in The Netherlands—as a case for an urban context of reduced crime levels, we provide a critique on the use of standardised surveys for measuring safety perceptions by administrators and its presupposed connection to factual crime. Contrasting survey results from the Rotterdam Safety Index with qualitative data from 64 in-depth interviews in four districts, the qualitative narrative contradicts findings from the survey and implies more nuanced and diversified policy responses to safety issues. The findings also show that decreasing factual crime and worsening safety perceptions do not necessarily constitute a paradox. Because of the tendency of surveys to connect safety perceptions to factual crime, their unsuitability to catch subtle perceptions and their inability to expose new viewpoints, we argue for de-quantification: a lesser dependency on—but not a repeal of—survey data in this area, supplemented by a periodic qualitative approach in researcing crime and safety information (qualitative monitoring).

Measuring Crime and Safety Perceptions: The Safety Index of Rotterdam

Rotterdam offers a notable case of an administration ‘seeing like a survey’ in crime and safety management. Being a large port town, Rotterdam is often regarded as a somewhat rough working-class city. During the 1980s and 1990s, crime problems increased in many disadvantaged areas, with drug-related crime, street prostitution and street robberies as the main topics of concern for residents, entrepreneurs and visitors. Social unrest about crime and safety in Rotterdam led to an administrative ‘regime change’ in 2002 (Tops 2007). For the first time, the Social Democrats lost their majority in the city council, with a new right-wing Populist Party (‘Liveable Rotterdam’) emphasising a clean-up of the city through intensive policing and attention to QoL issues (Van Swaaningen 2008). Many alterations in local crime and safety policy, however, represented a strengthening of policy ideas and implementations since the mid-1990s. Although welfarist policy interventions were also implemented, new control-like and civilising interventions clearly set a new tone (Barendregt and Van de Mheen 2009; Uitermark and Duyvendak 2008).

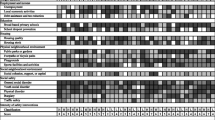

During the regime change, crime and safety became measured and communicated to the public via a new instrument: the Rotterdam Safety Index. Information from the index presently serves as a tool for implementing crime and safety interventions. The municipality presents an annual report of developments in crime and safety perceptions on the level of 14 districts and 71 neighbourhoods. At the same time, it serves as a public management tool for communicating successes of local safety policy responses in the form of fixed quantitative policy targets (Noordegraaf 2008). The Safety Index is composed of two types of data (see Fig. 1). On the one hand, there is an objective score based on the official records of crime and disorder from the municipality and the local police. On the other hand, there is a subjective score composed of survey data about perceptions regarding crime, safety, disorder and neighbourhood problems from 30,000 Rotterdam residents. All scores are calculated index scores and are constructed based on their deviation from average scores for the whole city in 2014. Over the years, the Safety Index has seen several methodological adjustments. It is now presented in conjunction with a Social and a Physical Index in a so-called Neighbourhood Profile in order to present a broader picture of conditions and QoL in Rotterdam neighbourhoods. The Neighbourhood Profile somewhat broadens the one-sided focus on ‘safety’ by showing at a glance what the spectrum of a neighbourhood on the three domains looks like, thus also highlighting the relative strengths of a district, such as physical environmental characteristics (e.g. the amount of green space).

Core elements of the Rotterdam Safety Index; Gemeente Rotterdam (2014)

Most political and media attention in Rotterdam, however, still focuses on the development of the Safety Index. Objective crime levels in the index have consistently decreased since the early 2000s. Yet, despite this positive development, for some years, there has been a slight deterioration in the subjective safety figures of the Safety Index (see Fig. 2). This trend goes against the improved crime figures. The index also shows that criminal offenses in Rotterdam between 2005 and 2012 fell by >20 %, but feelings of insecurity increased again. The percentage of respondents often or always feeling unsafe shows an upward trend since 2007, although its overall share in the index is limited (an increase from 3.7 % to 5.5 %). Additional statistical analyses of the index figures show that in many neighbourhoods, the perception of development of local problems is worse than the actual objective development—in particular, for burglary, rubbish on the streets and drug-related disorder (Snel et al. 2015). The objective–subjective discrepancy has led Rotterdam officials to wonder whether the city is experiencing a ‘crime paradox’. However, data analysis from The Netherlands Central Bureau for Statistics (CBS) does not corroborate this picture. According to CBS data, feelings of safety in Rotterdam show a significant and sizable improvement since 2002, just as other large Dutch cities (Akkermans 2015). Rotterdam even presented the strongest decline in the percentage of people regularly feeling unsafe over the period 2006–2014. Perhaps one reason for the difference in outcomes between the Safety Index and CBS data is the use of a different measurement (i.e. the percentage of people who regularly feel unsafe instead of always or often).

Safety Index Rotterdam 2003–2013; Snel et al. (2015)

Research Questions, Data and Methods

The discrepancy between objective and subjective data in the Rotterdam Safety Index led to political discomfort in the city council and was one of the reasons the qualitative research reported in this study was commissioned (see Lub and de Leeuw 2015). It was a direct result of the city’s predominant quantitative research approach used to measure crime and safety since the early 2000s. The city government is informed by statistical trends but it is less informed about the ways residents experience and view these trends. Are residents aware of the decline in crime and disorder in the city in the last decade? What kind of information influences their perceptions of crime and safety? What do they know about and expect from the local government in keeping their environment safe? The central research question of our study was thus formulated in an explorative manner: What does local safety mean for Rotterdam residents, and how do they view its temporal, spatial and political aspects?

Our research was divided into the following three dimensions, each with their correlating themes and questions (Table 1):

Area Selection

The field work was spatially spread around the territory of Rotterdam (see Fig. 3). We selected four contrasting research locations that differ on three specific criteria:

-

(a)

Discrepancy between objective and subjective scores in the Rotterdam Safety Index (subjective < objective versus subjective > objective)

-

(b)

Geographical location within the city’s territory (central versus peripheral areas and north versus south from the Meuse River)

-

(c)

Sociocultural and socioeconomic composition (heterogeneous versus homogenous population areas and low-income versus more affluent areas)

Location 1 represents a small, dense and mainly low-income area close to the city centre, with older housing and a multicultural composition (>60 % non-native Dutch); this area performs subjectively slightly better than the objective crime statistics, but both indices are below the city’s average. Location 2 is a more affluent area in the northern part of the city, with mixed housing types, more public space and a more homogenous social make up (mainly native Dutch residents); this area performs subjectively far better than its objective safety level, and both indices are above the city’s average. Location 3 represents a mixed-income area in the southeastern part of the city with mainly low-cost social housing and a multicultural composition (∼50 % non-native Dutch); the subjective index figure is below the objective index figure, and both indices are below the city’s average. Location 4 is a suburban area 25 km from the city centre with mixed housing types and a largely homogenous Native Dutch population; the subjective score is equal to the objective score and above the city’s average (Table 2).

Data and Methods

Our data were gathered from both in-depth interviews with residents and field observations. In total, 64 residents were interviewed according to a purposive sample, in terms of individual characteristics matching with the demographic, sociocultural and socioeconomic characteristics of the four neighbourhoods. In locations 1 and 3, for example, we succeeded in obtaining an ethnically mixed sample of respondents. In locations 2 and 4, respondents more often were of native Dutch descent and from senior age groups, representing the wider composition of the neighbourhood.

Observations of public meetings and informal street interviews provided information about neighbourhood dynamics and enabled us to recruit respondents from several social networks. This fieldwork often yielded respondents who are normally difficult to reach for formal research purposes—for instance, people who are not actively involved in local projects or are unfamiliar with filling out formal questionnaires. In some districts, respondents were more willing to participate than in others. In districts with an ethnically diverse composition, a lower socioeconomic status and a richer history of safety issues (locations 1 and 3) residents were more willing to talk about safety. Residents in the quieter and wealthier districts (locations 2 and 4) more often had little personal experience with and knowledge about local safety issues in the past and present. This does not imply, however, that they were less eligible as respondents—just that they were more difficult for us to reach. The main concern, however, was to develop theoretically representative concepts about their safety perceptions. The research aim was to discover and represent relevant qualities of the phenomenon under study, rather than statistically estimate how these qualities were distributed in particular populations or geographical areas (i.e. theoretical sampling; see also Beuving and de Vries 2015, pp. 57–58). Because of the constant reflection in a cyclical iterative process of data collection and analysis (Strauss and Corbin 1998), findings presented in this article ultimately are the result of a diverse data set, which is broadly representative of the four districts evaluated.

We conducted semistructured interviews using open-ended questions covering the aforementioned temporal, spatial and political dimensions related to safety perceptions, as well as residents’ opinions about related issues, such as their experiences with local professionals and civil servants, or any topic that might possibly be related to their feelings of safety. Interviews were conducted in respondents’ homes or public facilities (e.g. community centres) and lasted from approximately 1–1.5 or 2 h. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. We conducted a thematic analysis of data in the transcripts based on a method of grounded theory coding (see Strauss and Corbin 1998). This yielded a first level of code labels, which we then triangulated in a data matrix (see Anfara et al. 2002). For each research theme, all code labels that emerged from a particular location were placed in the rows of the matrix and ‘checked’ whether they corresponded to other locations in the columns. In this way, we could map overarching themes and identify differences between the respective research locations. These emergent themes formed a second level of analysis, from which we constructed the main conclusions.

Findings from the Fieldwork

Temporal and Spatial Dimensions of Neighbourhood Safety: Contradictory Results

An immediate finding emerging from our research data is that residents in all areas are predominantly positive about the crime level they experience. Respondents acknowledge that progress has been made in tackling crime and safety issues in the last decade and a half. They often recall problems of crime and safety in the past, which they no longer experience, such as hard drug abuse in public spaces, street prostitution and street robberies. Residents often connect these perceptions of progress with local safety interventions from the 1990s and early 2000s, such as stop-and-search policies, prohibition of public gatherings and intensive drug hot-spot policing. In other words, our data reflect a strong narrative of governmental crime-fighting success for the city of Rotterdam. Perhaps this is not a surprising result considering the regime change with its strong emphasis on tackling crime (Tops 2007). But it does somewhat contradict the picture from the Rotterdam Safety Index, which indicates that social safety is currently under pressure. The following quote from a café owner in location 1 illustrates the narrative of most of our respondents:

‘You can see it everywhere, really. How the city has been cleaned up. There is less street crime and stuff. It is completely different from when I grew up here. I think it has improved a lot for all the neighbourhoods in Rotterdam. You just see it, you notice it, you can feel it.’

We also found contradictory results regarding spatial dimensions of safety perceptions in the ‘troubled’ and ‘less-troubled’ areas (taking results of the Rotterdam Safety Index into account). Where we expected more reports of insecurity in troubled neighbourhoods, we actually recorded a narrative of relative confidence of respondents in the public space and trust in ‘deviant others’ (Young 1999). In the eyes of respondents from ‘troubled’ areas (locations 1 and 3), the most problematic aspects of crime have been tackled, and their neighbourhood’s culturally diverse population now seems to contribute to a certain social comfort with people differing from their own status group. Presently, negative perceptions in these areas are not so much geared towards fear of crime but towards fear of stigmatisation of their own area in the media. It shows criticism about the way the local government approaches their area—for instance, questioning stop-and-search policies in their neighbourhood for risk of ethnic profiling (see also Reitzel and Piquero 2006), as a retired Turkish respondent from location 1 explained:

‘Those preventive stop-and-search interventions I do not support. If there is a reason to search people, okay. But do not just stop someone and search their body. Is that not racist?’

In the ‘less troubled’ areas, however, respondents communicate concerns about safety, framing it in terms of demographic changes and attributing local problems to ‘deviant others’, like youth groups of Moroccan descent, eastern European immigrants and disorderly people from other neighbourhoods. Karn (2007) recorded similar tendencies in an English neighbourhood when she observed how people categorise each other on the basis of purity and morality. This sentiment does not always result in a narrative of personal victimisation or fear of victimisation. But it does indicate an emotion among residents that demographic developments jeopardise the peace in their more quiet and homogenous neighbourhoods. Triangulating these findings with the two heterogeneous areas, it appears that under favourable social conditions (i.e. a generally safe public space), social and cultural diversity can create tolerance and less fear of deviating others, whereas homogeneity (as seen in the ‘safer’ locations 2 and 4) constitutes a disposition for fear of people deviating from one’s own status group. In other words, as Blau (1977) theorised: homogenous groups turn inwards and heterogeneous groups outwards, but only when social conditions are favourable. Note, however, that the homogeneous peripheral areas we investigated displayed generally positive Rotterdam Safety Index scores. Yet the narrative about ‘safety under pressure’ in these areas is not visible in the index, because there are no questions about this topic in the survey, and the conditions at hand are too fine-grained to sift out via a questionnaire. A senior citizen from location 2 narrated how social and demographic changes can cause a sentiment of uneasiness:

‘Let me be clear: I strongly oppose people who are racist, but I must say, I grew up in this world, until roughly the mid-seventies. Well, there were barely any foreigners around back then! But since then, they’ve come in droves. They are different people with different norms and values and customs, and of course you notice. You now see more black people hanging out on street corners. It does influence how safe you feel.’

Moreover, in the homogenous areas, the narrative of the alleged demographic changes is strongly mediated through symbolic interactions of insecurity, and these feelings in turn are almost exclusively projected onto immigrants. Yet the symbolic mediation of fear of crime does not exclusively limit itself to the homogenous areas or demographic changes. Our fieldwork identified many insecurity experiences primarily based on incomplete, mediated and decontextualised information. The input respondents gave regarding local safety show that perceived security risks often play a more prominent role than do concrete, objective knowledge and experiences. Such insight is obscured from survey figures. Respondents, for example, testify to vague incidents from the past or to hearsay or apply general media coverage about a certain topic (e.g. robbery or assault) to their personal situation, even when there is no immediate cause for it. This type of risk awareness can be functional when it corresponds to real dangers and threats. Media reports and an oral tradition of rumours about local disorder and crime incidents, however, often contribute negatively to people’s image of public safety and their own personal feelings, as the chairman of a homeowners association from location 2—with low crime figures and a dominant senior and Native Dutch population—illustrates:

‘As the chairman of the owners association, I often speak to older resident ladies here. Well, they have four locks on the door. There’s even a lady that has placed an additional camera on her door even though we have a videophone system for the building. If you speak to them they always say: ‘I’m so frightened, I bought a bag that I can wear under my sweater, so if I go out the door I never have a handbag with me.’ I find that pretty extreme, but all those elderly people read the newspapers, they see it on television, they see the most horrible things. And they apply it to their own situation: it could also happen here.’

Political Dimensions of Neighbourhood Safety: An Ambivalent Narrative

As mentioned, respondents indicate that safety in the city and the QoL in their environment has improved considerably since the early 2000s. They indicate that local security policy has contributed to this. This perception is especially strong among residents of neighbourhoods where drug-related crime and disorder were pervasive problems in the 1980s and 1990s. Residents in these areas have become somewhat accustomed to the influence of government intervention regarding crime and disorder and compare their current situation with ‘how it was before’. They now more or less expect the government to treat their area with priority and are of the opinion that although visible crime and disorder have decreased, the conditions that can give rise to them (poverty, domestic violence, lack of social perspectives for youth) have not, and that therefore their area is still in a precarious balance. In the eyes of respondents, current local sociopolitical and socioeconomic developments—such as austerity measures, administrative reorganisation and a reduced capacity of law enforcement—could swing the pendulum back to disorder and crime. A variety of factors create concerns about the consolidation of security in the neighbourhood: decreased visibility of the police, social workers and city wardens, and fewer places where residents can turn to such professionals. Although respondents acknowledge that the problems are not as grave as in the past, residents from previously crime-ridden areas do ask that maintenance and management relating to security issues be retained and strengthened. In other words, disorder and crime in Rotterdam have improved considerably in recent years, but recovery is still perceived as fragile in some places. A 39-year-old single resident of location 1 explains:

‘The classic stereotype junk which causes a lot of problems, you don’t really see that person anymore. I also feel that in recent years the city made great efforts to maintain things, clean up the streets, timely removal of garbage, things like that. The city came to understand how important it is to control things to prevent further degeneration. But it should be a lasting investment. Because this is the type neighbourhood that if efforts should weaken, it can easily slip back.’

The narrative shows ambivalence on this topic because at the same time, support for a repressive zero-tolerance rhetoric and policy among residents has somewhat diminished now that the most visible security problems are under control. In the lower-status neighbourhoods (locations 1 and 3), where there is a longer history of tougher monitoring and enforcement policies, there is also more awareness of the disadvantages of such law enforcement. The narrative here is that law enforcement also has to engage with disorderly persons instead of disciplining them and the mandate to stop and search can lead to ethnic profiling, such as excessive control of mostly immigrant youth. This finding is probably related to the fact that we interviewed an ethnically diverse population in locations 1 and 3 that is more sensitive to ethnic profiling than a majority white middle-class population. Respondents from the more affluent locations 2 and 4 are much less susceptible to the adverse effects of repressive security measures, such as stop and search. Because of their more ‘favourable’ sociocultural disposition, residents in these areas are much less likely to experience the disadvantages of such local crime and disorder policy. Moreover, their aforementioned symbolically mediated fear of the ‘deviant other’ causes them to be less critical of this type of policy.

A similar ambivalent narrative is apparent in the general stance towards local government. This finding applies to all four neighbourhoods. Analysis shows that trust in government as an overall system is fragile. It is often temporary, locally determined, not widely shared and subject to change. Trust in government related to specific agents, however—e.g. a particular police officer or civil servant—is much greater. Nonetheless, there are regular complaints and frustrations. Residents frequently experience disinterest from administrators and local civil servants with respect to their own voluntary involvement in their own neighbourhood. There seems to be a dynamic of apathy and withdrawal, even with the more highly educated respondents. Most respondents are barely interested in politics. Often heard complaints are: ‘It is too far removed from me’, ‘It does not make any sense’ or ‘Local politicians ultimately do what they want’. This is reminiscent of what Merton (1938) called ‘retreatism’: those who no longer adhere to the generally accepted cultural goals and means can withdraw from public life, in this case the domain of local politics and active citizenship.

Moreover, residents regularly criticise the political implications of particular outcomes of the municipal Rotterdam Safety Index, fearing cutbacks or administrative negligence. They feel that the local problems they identify in their environment are not always mentioned in the index. Residents in location 4, for instance, experience the very high security rating as appropriate in relation to most Rotterdam neighbourhoods but see it as an underreporting of safety and QoL issues when related to surrounding towns outside the municipal borders of Rotterdam, which are more similar in terms of population and atmosphere. A politically active resident from location 4 explains:‘Each year on the Safety Index we score a 10. But it is a disaster. We have already said it a thousand times: compared with most areas in Rotterdam that 10 might give a realistic image. But we are not in Rotterdam. We are thirty-two kilometres from the city centre and culturally we are more part of the Westland area. That is essentially our standard. And compared with the wider Westland area, we would absolutely not score a 10 but a 7.’

Such an ambivalent political sentiment has a self-reinforcing effect on safety perceptions, because as a result, negative experiences with the government are often more easily remembered than positive experiences. Municipal projects like neighbourhood watch patrols, positive communication and reputation management, such as neighbourhood branding, are met with enthusiasm only if they are supported by a visible and permanent follow-up to concrete safety problems from individual civil servants (Lub 2013). Examples of co-production of public safety measures from our data show how cooperation and communication with residents can contribute to an understanding of government policies and subsequently feelings of social safety. A resident and entrepreneur (a chip peddler) in location 3—with an ethnically diverse population and above-average crime figures—illustrates this dynamic.

‘Many people see this area like a ghetto. I don’t understand that. It is not based on facts. When I bought this business, I also became more active with the neighbourhood. And then I became involved in the governing process and started to look differently at the municipality, and to the police, because you work with them. So then you become a small part of it. At some point you even become a kind of ambassador for your neighbourhood. People always complain about the police and the municipality. But now I explain that it is more complicated than it seems.’

Conclusions and Discussion

The research presented here shows that qualitative inquiry into perceptions of neighbourhood safety can: (1) yield opposite results from those of survey questionnaires; (2) expose nuanced, previously obscured viewpoints of safety perceptions of residents and the political/policy implications connected to them; (3) present specific directions for future research and relevant administrative responses to local safety problems. Based on our 64 interviews with individuals from four different neighbourhoods in the city of Rotterdam, we conclude that perceptions of safety are more complex and socially meaningful than quantitative measurement presupposes. Though this conclusion does not undermine the use of a policy tool like the Rotterdam Safety Index, it does debunk its importance when prioritising and legitimising policy responses in neighbourhoods.

Perhaps the most significant finding in this regard is that temporal, spatial and political dimensions that comprise the safety narrative of residents can show quite a different picture than survey data suggest, implying alternative policy responses. Feelings of safety strongly connect to broader macrosocial contexts that transcend the immediate neighbourhood (crime) level, like the impact of demographic changes, faith in government actions and media coverage on crime topics. In particular, in European cities that, like Rotterdam, witnessed a significant improvement in factual crime levels since the early 2000s, Lerner’s Just-World perspective may be an important theoretical lens in understanding future safety perceptions (Eysink-Smeets 2016; see Lerner and Miller 1978). Lerner argues that in order to feel safe, above all, people need to believe that the world around them is just. Yet it is conceivable that developments concerning migration and the democratic crises in European societies will increase a sentiment of injustice and discontent, further pressuring the relations between urban populations. In our own research, perceptions of residents about ‘unjust’ government actions—such as ethnic profiling in disadvantaged heterogeneous neighbourhoods, or concerns about unwanted newcomers in the more affluent, homogeneous neighbourhoods—serve as illustrations. As a result, perception of safety may be compromised further, possibly decreasing social cohesion and local active citizenship, albeit now in a very different way than before; not by crime but by macro social changes (cf. Eysink-Smeets 2016).

As for policy implications, this means that urban governments should give more attention to safety perceptions in areas that are not on the city’s traditional crime radar. For years, the main policy focus was on making crime-ridden (inner-city) areas safer. This has been a justifiable policy. But precisely in districts that usually do not surface in crime surveys, there might be tensions brewing (e.g. fear of the deviant other). Moreover, the media have a tendency to exacerbate these tensions by symbolic mediation, and trust in government is characterised by ambivalence. For these reasons there should be more focus on personal information services to citizens. The symbolic mediation of safety feelings does not mean that municipal policy cannot influence these perceptions. But it does require more insight into local sentiments and possibilities of redirecting and contextualising information from third parties, such as the media and active residents in the area who communicate about crime and safety (via, for instance, social media like Facebook and Twitter). If residents are more aware of what actually plays out in the field of security, what local authorities are doing about it and what effects policies have, the negative influence of the mass media can be softened. This requires a policy that—in line with Habermas’ Theory of Communicative Action (1981)—operates outside the ‘system’ of civil servants (with its geographical focus) and focuses more on the social life-world of citizens. The perceived safety of city residents depends on much more than just the state of one’s own neighbourhood.

At a methodological level, our findings suggest a moderate approach to survey design. Surveys used for local crime and safety perceptions often present dozens of items. The question is whether this type of statistical information from geographical areas produces useful knowledge (Uitermark et al., unpublised data). It can lead to a plethora of variables whose results are difficult to interpret and can cause confusion. How is it possible to reach a more methodologically sound mode of research? A first consideration in the collection of safety information is data dequantification. The positivist, numerical discourse dominant in today’s collection of crime data—city governments ‘seeing like a survey’ (Law 2009)—runs the risk of severing social research from social experience (see also Beuving and de Vries 2015). Our own naturalistic research demonstrates how social research that does not acknowledge social experience can become sterile and, in the long run, confounding for policy makers. Therefore, a significant reduction in the number of subjective variables in crime surveys to a few key, baseline, items is preferred. Such a dequantifying approach should be complemented by a periodic qualitative explorative monitoring and analysis of the social construction of meaning about crime and safety. This is necessary in order to gain insight into the complexity of reported subjective safety in surveys. In this way, the two methodological strands profit from input of the other (see also Teddlie and Tashakkori 2009). Unlike conventional survey questionnaires, qualitative inquiry does not assume the phenomena under study to be a preordered configuration but aims to capture its dynamics and contexts (Beuving and de Vries 2015).

Of course, putting the qualitative research approach of neighbourhood safety on par with survey questionnaires poses political challenges and methodological dangers. City governments have become accustomed to exert organisational and political control on the basis of numerical data. The technocratically governed urban centres of our day are geared towards decision making by statistical analysis, not towards ‘story telling’. Achieving a legitimate status of qualitative research within administrative decision making will require a change of mentality (Lub 2015). There is a pragmatic interest in quantification—in applying statistical techniques that can analyse large amounts of data. ‘Bigger’ is seen as ‘better’ and—in theory, at least—quantification makes it possible to unambiguously compare empirical findings from different contexts, which is more difficult with data from qualitative studies (see Kvale 1994). The use of numerical data also has an important rhetorical function when it comes to convincing a particular constituency or the media. In a technocracy, figures are often identified with facts and hard metrics thereby are considered more reliable than qualitative insights. The Rotterdam Safety Index itself is a prime example, as it serves as a public management tool for communicating successes of local safety policy responses in the form of fixed quantitative policy targets. From a methodological standpoint, qualitative research poses the danger of being made subordinate to quantitative data or deployed in an ad hoc fashion, solely to probe very particular issues or to find out ‘what’s going on’ when the figures do not make sense. Qualitative investigations also run the risk of superficial execution or analysis, especially when nonindependent, underqualified or uncritical researchers are deployed to carry out the research for local governments. Qualitative research into safety perceptions is a cyclical iterative process that forces researchers to constantly reflect on findings and seek patterns that slowly reveal themselves in the research process. Outsourcing this type of inquiry to graduate students or quick-and-dirty consultants can jeopardise its validity.

In sum, qualitative research by its own right can provide a sharper and more concrete view of insights residents provide regarding their personal perceptions of safety and local variations therein, provided it is done repeatedly and with political commitment and methodological rigour. Moving away from the one-sided dependency on quantitative data and providing room for qualitative insights can open up new perspectives for future research into safety perceptions and its proper policy response.

References

Akkermans, M. (2015). Criminaliteit en veiligheidsbeleving - Landelijke en regionale trends. The Hague: CBS.

Altheide, D. L. (1997). The news media, the problem frame, and the production of fear. The Sociological Quarterly, 38, 647–668.

Anfara, V. A., Brown, K. M., & Mangione, T. L. (2002). Qualitative analysis on stage: making the research process more public. Educational Researcher, 2002, 28–38.

Austin, D. M., Allen Furr, L., & Spine, M. (2002). The effects of neighbourhood conditions on perceptions of safety. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30, 417–427.

Ajzen, I., & Krebs, D. (1994). Attitude theory and measurement: Implications for survey research. In I. Borg & P. P. Mohler (Eds.), Trends and perspectives in empirical social research (pp. 250–261). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

Barendregt, C., & van de Mheen, D. (2009). Then there was silence on the streets. Developments in the streets scene of Rotterdam in the last decade. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 16(6), 497–511.

Bauman, Z. (2001). Communities; seeking in an insecure world. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society; towards a new modernity. Londen: Sage Publications.

Beuving, J., & de Vries, G. (2015). Doing qualitative research. The craft of naturalistic inquiry. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Bishop, G. F., Oldendick, R. W., & Tuchfarber, R. J. (1986). Opinions on fictitious issues: the pressure to answer survey questions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 50, 240–250.

Blau, P. M. (1977). Inequality and heterogeneity: a primitive theory of social structure. New York: Free Press.

Bruinsma, G. J. N., & Bernasco, W. (2004). De stad en sociale onveiligheid. Een State-of-the-Art van wetenschappelijke kennis in Nederland. Leiden: NSCR.

Ditton, J., Bannister, J., Gilchrist, E., & Farrall, S. (1999). Afraid or angry? Recalibrating the “fear” of crime. International Review of Victimology, 6, 83–99.

Duffy, B., Wake, R., Burrows, T., & Bremner, P. (2008). Closing the gaps – crime and public perceptions. International Review of Law Computers & Technology, 22, 17–44.

Erikson, R. S., Luttberg, N. R., & Tedin, K. T. (1988). American public opinion (3rd ed.). New York: Macmillian.

Eysink-Smeets, M. (2016). Veiligheidsbeleving in Rotterdam. Rotterdam: Hogeschool Inholland.

Eysink-Smeets, M. W. B., Moors, J. A., van ‘t Hof, K., van den Reek-Vermeulen, E. W. A. (2010). Omgaan met de perceptie van overlast en verloedering. Een beknopt advies voor de bestuurspraktijk. Den Haag/Tilburg: Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties/IVA Beleidsonderzoek en Advies.

Farrall, S., Bannister, J., Ditton, J., & Gilchrist, E. (2000). Social psychology and the fear of crime: re-examining a speculative model. British Journal of Criminology, 40, 399–413.

Farrall, S. D., Jackson, J., & Gray, E. (2009). Social order and the fear of crime in contemporary times. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ferraro, K. F. (1995). Fear of crime: interpreting victimization risk. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Ferrell, J. (2009). Kill method: a provocation. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Criminology, 1(1), 1–22.

Furedi, F. (1997). Culture of fear. Risk-taking and the morality of low expectation. Londen: Cassell.

Habermas, J. (1981). Theory of communicative action, volume two: lifeworld and system: a critique of functionalist reason. Boston: Beacon.

Joh, E. E. (2014). Policing by numbers: big data and the fourth amendment. Washington Law Review, 89, 35–68.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking fast and slow. New York: FSG.

Karn, J. (2007). Narratives of neglect: community, regeneration and the governance of security. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Kleinhans, R., & Bolt, G. (2013). More than just fear: on the intricate interplay between perceived neighborhood disorder, collective efficacy, and action. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(3), 420–446.

Kvale, S. (1994). Ten standard objections to qualitative research interviews. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 25(2), 147–173.

Law, J. (2009). Seeing like a survey. Cultural Sociology, 3(2), 239–256.

Lee, M., & Farrall. (2009). Fear of crime: critical voices in an age of anxiety. Oxon: Routledge.

Lerner, M. J., Miller, D. T. (1978). Just world research and the attribution process: looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85(5), 1030–1051.

Lub, V. (2013). Schoon, heel en werkzaam? Een wetenschappelijke beoordeling van sociale interventies op het terrein van buurtleefbaarheid. Den Haag: Boom Lemma uitgevers.

Lub, V. (2015). Validity in qualitative evaluation: linking purposes, paradigms and perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 1–8.

Lub, V., & de Leeuw, T. (2015). Veiligheidsbeleving in Rotterdam. Een onderzoek naar percepties, ervaringen en waardering van beleid. Rotterdam: Bureau voor sociale argumentatie.

Maas, J., Spreeuwenberg, J. M., van Winsum-Westra, M., Verheij, R. A., de Vries, S., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2009). Is green space in the living environment associated with people’s feelings of social safety? Environment and Planning A, 41, 1763–1777.

McCue, C. (2014). Data mining and predictive analysis: intelligence gathering and crime analysis. Oxford: Elsevier.

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672–682.

Miller, J., & Palacios, W. R. (2015). The value of qualitative research for advancing criminological theory. In J. Miller & W. R. Palacio (Eds.), Qualitative research in criminology. Advances in criminological theory volume 20 (pp. 1–11). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Noordegraaf, M. (2008). Meanings of measurement. The real story behind the Rotterdam Safety Index. Public Management Review, 10(2), 219–237.

Rapley, M. (2003). Quality of life research: a critical introduction. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Reitzel, J., & Piquero, A. R. (2006). Does it exist? Studying citizens’ attitudes of racial profiling. Police Quarterly, 9(2), 161–183.

Rodríguez, J. A., Pérez-Santiago, N., & Birkbeck, C. (2015). Surveys as cultural artefacts: applying the international self-report delinquency study to Latin American adolescents. European Journal of Criminology, 12(4), 420–436.

Romer, D., Jamieson, K. H., & Aday, S. (2003). Television news and the cultivation of fear of crime. Journal of Communication, 53(1), 88–104.

Schuman, H., & Presser, S. (1981). Questions and answers in attitude surveys. New York: Academic.

Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Hippler, H. J., Strack, F., & Sudman, S. (1994). Cognitive and communicative aspects of survey management. In I. Borg & P. P. Mohler (Eds.), Trends and perspectives in empirical social research (pp. 40–54). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

Snel, E., ‘t Hart, M., Leerkes, A. (2015). Mind the Gap: Veiligheid en veiligheidsbeleving in Rotterdam. Onderzoek in opdracht van de Directie Veiligheid, Gemeente Rotterdam.

Sparks, R., Girling, E., & Loader, I. (2001). Fear and everyday urban lives. Urban Studies, 38, 885–898.

Stanko, B. (1995). Women, crime and fear. The Annals of the American Academy of Politics and Social Science, 539, 46–59.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. New York: Sage.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Tops, P. (2007). Regimeverandering in Rotterdam: hoe een stadsbestuur zichzelf opnieuw uitvond. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Atlas.

Tulloch, M. (2000). The meaning of age differences in the fear of crime. British Journal of Criminology, 40(3), 451–467.

Uitermark, J., & Duyvendak, J. W. (2008). Civilising the city: populism and revanchist urbanism in Rotterdam. Urban Studies, 45(7), 1485–1503.

Ullman, S. E. (1997). Review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 24(2), 177–204.

van Swaaningen, R. (2008). Sweeping the street: Civil society and community safety in Rotterdam. In J. Shapland (Ed.), Justice, community and civil society: a contested terrain across Europe (pp. 87–106). Devon: Willan Publishing.

Von Hofer, H. (2000). Crime statistics as constructs: the case of Swedish rape statistics. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 8, 77–89.

Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., Sloan, L. (2016). Crime sensing with big data: the affordances and limitations of using open source communications to estimate crime patterns. The British Journal of Criminology, Open Source. doi:10.1093/bjc/azw031.

Wood, L., Shannon, T., Bulsara, M., Pikora, T., McCormack, G., & Giles-Corti, B. (2008). The anatomy of the safe and social suburb: an exploratory study of the built environment, social capital and residents’ perceptions of safety. Health & Place, 14, 15–31.

Young, J. (1999). The exclusive society. London: Sage.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lub, V., de Leeuw, T. Perceptions of Neighbourhood Safety and Policy Response: A Qualitative Approach. Eur J Crim Policy Res 23, 425–440 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-016-9331-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-016-9331-0