Abstract

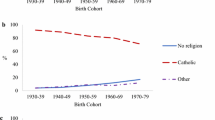

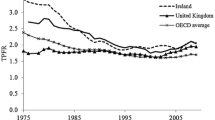

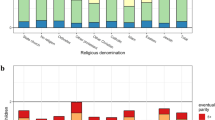

This article aims to assess the role of religion and religiousness in engendering higher US fertility compared to Europe. Religion is important in the life of one-half of US women, whereas not even for one of six Europeans. By every available measure, American women are more religious than European women. Catholic and Protestant women have notably higher fertility than those not belonging to any denomination in the US and across Europe. In all European regions and in the United States as well as among all denominations the more devout have more children. However, women in Northern and Western Europe who are the least religious have equivalent or even higher fertility than women in the US, and notably higher fertility than those in Southern Europe. This suggests that forces other than religion and religiousness are also important in their impact on childbearing. A multivariate analysis demonstrates that relatively “traditional” socio-economic covariates (age, marital status, residence, education, and income) do not substantially change the positive association of religiousness and fertility. Finally, if Europeans were as religious as Americans one might theoretically expect a small fertility increase for Europe as a whole, but considerably more for Western Europe.

Résumé

Religion, religiosité et fécondité aux Etats-Unis et en Europe. L’objectif de cet article est d’évaluer les rôles de la religion et de la religiosité comme déterminant du taux de fécondité plus élevé aux Etats-Unis qu’en Europe. La religion occupe une place importante dans la vie de la moitie des femmes américaines, tandis qu’elle n’est importante que pour 1 européenne sur 6. Quelque soit l’indicateur utilisé, les américaines sont plus religieuses que les européennes. Les femmes catholiques et protestantes ont une fécondité significativement plus élevée que celles sans affiliation religieuse aux Etats-Unis et en Europe. Dans toutes les régions de l’Europe et aux Etats-Unis, ainsi qu’à travers toutes les pratiques religieuses, les plus croyants ont plus d’enfants. Toutefois, les femmes d’Europe du Nord et de l’Ouest, qui sont les moins religieuses, ont une fécondité équivalente ou supérieure aux femmes américaines, et significativement plus élevée que leurs consœurs d’Europe du Sud. Ce constat suggère que des forces autres que la religion ou la religiosité ont aussi un impact important sur la fécondité. Une analyse multivariée montre que les variables socioéconomiques classiquement considérées (âge, statut marital, lieu de résidence, éducation et revenus) ne changent pas substantiellement l’association positive entre religiosité et fécondité. Au final, si le niveau de religiosité des Européennes était équivalent à celui les Américaines, on pourrait théoriquement attendre une légère augmentation de la fécondité en Europe en général, mais de manière beaucoup plus prononcée en Europe de l’Ouest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Values of data for the European Union after 1 May 2004 comprised by 25 countries are almost the same, but the available time series is shorter, which is the reason why the EU 15 was included in the table.

Religious participation is defined as a positive response to the survey question attending services “more than once a week” or “once a week.”

In the US, the importance of religion is dichotomized into “very important” (51%) and “somewhat or not important” (49%). In Europe, the dichotomy is “important or very important” (46%) and “not important” (54%). In the US, the frequency of church attendance is dichotomized into more (50%) and less (50%) than once a month. In Europe, the dichotomy is more (59%) and less (41%) than once a year.

References

Adsera, A. (2004). Marital fertility and religion: Recent changes in Spain. Discussion paper, no. 1399, IZA (Institute for the Study of Labor), Bonn.

Bélanger, A., & Ouellet, G. (2002). A comparative study of recent trends in Canadian and American fertility, 1980–1999. In A. Bélanger (Ed.), Report on the demographic situation in Canada (pp. 107–136), 2001. Statistics Canada, Cat. No. 91-209-XPE. Ottawa.

Berger, P. (2005). Statement at roundtable “Secular Europe and religious America: Implications for transatlantic relations”. The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, April 21, pp. 1–4.

Billings, J. S. (1889). Vital statistics of the Jews in the United States. Census Bulletin, 19, 4–9.

Caldwell, J., & Schindlmayr, T. (2003). Explanations of the fertility crisis in modern societies: A search for commonalities. Population Studies, 57(3), 241–263.

Coale, A. J., & Zelnick, M. (1963). New estimates of fertility and population in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

DellaPergola, S. (1980). Patterns of American Jewish fertility. Demography, 17(3), 261–273.

Frejka, T. (2004). The ‘curiously high’ fertility of the USA. Population Studies, 58(1), 88–92.

Frejka, T., & Sardon, J.-P. (2004). Childbearing trends and prospects in low-fertility countries: A cohort analysis. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Goldscheider, C. (1967). Fertility of the Jews. Demography, 4(1), 196–209.

Goldscheider, C. (1971). Population, modernization, and social structure. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Goldscheider, C. (1999). Religious values, dependencies, and fertility: Evidence and implications from Israel. In R. Leete (Ed.), Dynamics of values in fertility change (pp. 310–330). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldscheider, C. (2006). Religion, family, and fertility: What do we know historically and comparatively? In R. Derosas & F. van Poppel (Eds.), Religion and the decline of fertility in the western world (pp. 41–57). Springer.

Goldscheider, C., & Mosher, W. D. (1991). Patterns of contraceptive use in the United States: The importance of religious beliefs. Studies in Family Planning, 22, 102–115.

Goldstein, J. R., Lutz, W., & Testa M.-R. (2003). The emergence of sub-replacement fertility ideals in Europe. Population Research and Policy Review Policy Review, 22(5–6), 479–496.

Greeley, A. M. (2002). Religion in Europe at the end of the second millenium: A sociological profile. Transaction Publishers.

Greeley, A. M. (2004). Religious decline in Europe? America. The National Catholic Weekly, 190(1), 16–19.

Hobcraft, J., & Kiernan, K. (1995). Becoming a parent in Europe. Evolution or revolution in European population. In Proceedings of the European population conference, Milano.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1998). Introduction to the economics of religion. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(3), 1465–1495.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1991). The Consequences of religious market structure: Adam Smith and the economics of religion. Rationality and Society, 3(2), 156–177.

Iannaccone, L. R., Finke, R., & Stark, R. (1997). Deregulating religion: The economics of church and state. Economic Inquiry 35(2), 350–364.

Iannaccone, L. R., Stark, R., & Finke, R. (1998). Rationality and the ‘religious mind’. Economic Inquiry, 36(3), 373–389.

Immerman, R. S., & Mackey, W. C. (2003). Religion and fertility. The Mankind Quarterly, XLIII(4), 377–405.

John Paul, II (2003). Ecclesia in Europa (The Church in Europe). Published in L’Osservatore Romano (English weekly edition), July 2

Hart, D. B. (2004). Religion in America: Ancient and modern. New Criterion, March, 5–18.

Kertzer, D. (2006). Religion and the decline of fertility: Conclusions. In R. Derosas & F. van Poppel (Eds.), Religion and the decline of fertility in the western world (pp. 259–269). Springer.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Moors, G. (2000). Recent trends in fertility and household formation in the industrialized west. Review of Population and Social Policy, 9, 121–170.

Macura, M., & MacDonald, A. L. (2003). Fertility and fertility regulation in Eastern Europe: From the socialist to the post-socialist era. In I. Kotowska & Jóźwiak (Eds.), Population of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw: Challenges and Opportunities.

McQuillan, K. (2004). When does religion influence fertility? Population and Development Review, 30(1), 25–56.

Mead, W. R. (2005). Statement at roundtable “Secular Europe and religious America: Implications for transatlantic relations. The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, April 21, pp. 6–8.

Morgan, S. P. (2003). Is low fertility a twenty-first-century demographic crisis? Demography, 40(4), 589-603

Mosher, W. D., Williams, L. B., & Johnson, D. P. (1992). Religion and fertility in the United States: New patterns. Demography, 29(2), 199–214.

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2004). Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Observatoire Démographique Européen. (2006). Personal communications.

Pew Research Center. (2002). Among wealthy Nations U.S. stands alone in its embrace of religion (http://people-press.org/).

Pew Research Center. (2003). Anti-Americanism: Causes and characteristics. (http://people-press.org/).

Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2004). American religious landscapes and political attitudes. http://pewforum.org/docs/index.php?DocID=55

Sardon, J.-P. (2004). Recent demographic trends in the developed countries. Population, 59(2), 263–314 (English edition).

Sobotka, T., & Adigüzel, F. (2003). Religiosity and spatial demographic differences in the Netherlands. SOM Research Report 02F65, University of Groningen (www.ub.rug.nl/eldoc/som/f/02F65/02F65.pdf).

Surkyn, J., & Lesthaeghe, R. (2004). Value orientations and the second demographic transition (STD) in Northern, Western and Southern Europe: An update. Demographic Research, Special Collection 3, Article 3 (www.demographic-research.org).

van de Kaa, D. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42, 1–57.

Warner, R. S. (1993). Work in progress toward a new paradigm for the sociological study of religion in the United States. The American Journal of Sociology, 98(5), 1044–1093.

Weigel, G., (2005). The Cube and the Cathedral: Europe, America, and politics without God. Basic Books.

Westoff, C. F., & Bumpass, L. (1973). The revolution in birth control practices of U.S. Roman Catholics. Science, 179, 41–44.

Westoff, C. F., & Jones, E. F. (1979). The end of ‘Catholic’ fertility. Demography, 16(2), 209–217.

Westoff, C. F., & Ryder, N. B. (1977). The contraceptive revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wetrogan, S. (2003). Overview. In U.S. Census Bureau conference: The direction of fertility in the United States (pp. 1–2). Washington, DC: Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics (COPAFS).

Acknowledgements

The major effort for the whole project is supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation to the Population Resource Center. Thanks are further due to the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany, for partial financial support for Tomas Frejka. The authors appreciate the many useful comments provided by two anonymous reviewers and by the EJP editor. They also acknowledge the help of Judie Miller and Dawn Koffman of the Office of Population Research, Princeton University for secretarial and computing assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frejka, T., Westoff, C.F. Religion, Religiousness and Fertility in the US and in Europe. Eur J Population 24, 5–31 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-007-9121-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-007-9121-y