Abstract

A meaningful solution to an inversion problem should be composed of the preferred inversion model and its uncertainty and resolution estimates. The model uncertainty estimate describes an equivalent model domain in which each model generates responses which fit the observed data to within a threshold value. The model resolution matrix measures to what extent the unknown true solution maps into the preferred solution. However, most current geophysical electromagnetic (also gravity, magnetic and seismic) inversion studies only offer the preferred inversion model and ignore model uncertainty and resolution estimates, which makes the reliability of the preferred inversion model questionable. This may be caused by the fact that the computation and analysis of an inversion model depend on multiple factors, such as the misfit or objective function, the accuracy of the forward solvers, data coverage and noise, values of trade-off parameters, the initial model, the reference model and the model constraints. Depending on the particular method selected, large computational costs ensue. In this review, we first try to cover linearised model analysis tools such as the sensitivity matrix, the model resolution matrix and the model covariance matrix also providing a partially nonlinear description of the equivalent model domain based on pseudo-hyperellipsoids. Linearised model analysis tools can offer quantitative measures. In particular, the model resolution and covariance matrices measure how far the preferred inversion model is from the true model and how uncertainty in the measurements maps into model uncertainty. We also cover nonlinear model analysis tools including changes to the preferred inversion model (nonlinear sensitivity tests), modifications of the data set (using bootstrap re-sampling and generalised cross-validation), modifications of data uncertainty, variations of model constraints (including changes to the trade-off parameter, reference model and matrix regularisation operator), the edgehog method, most-squares inversion and global searching algorithms. These nonlinear model analysis tools try to explore larger parts of the model domain than linearised model analysis and, hence, may assemble a more comprehensive equivalent model domain. Then, to overcome the bottleneck of computational cost in model analysis, we present several practical algorithms to accelerate the computation. Here, we emphasise linearised model analysis, as efficient computation of nonlinear model uncertainty and resolution estimates is mainly determined by fast forward and inversion solvers. In the last part of our review, we present applications of model analysis to models computed from individual and joint inversions of electromagnetic data; we also describe optimal survey design and inversion grid design as important applications of model analysis. The currently available model uncertainty and resolution analyses are mainly for 1D and 2D problems due to the limitations in computational cost. With significant enhancements of computing power, 3D model analyses are expected to be increasingly used and to help analyse and establish confidence in 3D inversion models.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In geophysical electromagnetic induction methods (Nabighian 1991; Berdichevsky and Dmitriev 2008; Chave and Jones 2012), natural or artificial source currents generate the primary electromagnetic fields which propagate through the Earth. In conductive bodies and over interfaces with conductivity contrasts, induced currents and accumulated surface charges generate secondary magnetic and electric fields. Depending on the method, either the primary field plus the secondary field or the secondary field is measured at receivers. The secondary field carries information of the conductive bodies and the locations of interfaces with conductivity contrasts. Therefore, using inversion algorithms (Parker 1994; Tikhonov et al. 1995; Zhdanov 2002; Tarantola 2005; Aster et al. 2012; Menke 2012), we are able to extract the underground conductivity distribution from measured electromagnetic field data sets. Currently, geo-electromagnetic induction methods are widely used in studies of the shallow (\(<300\) m depth) subsurface (Tezkan 1999; Commer et al. 2006; Pedersen et al. 2006; Günther et al. 2006; Kalscheuer et al. 2007; Rodriguez and Sweetkind 2015; Merz et al. 2016; Abtahi et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2016; Costall et al. 2018) and monitoring and imaging of the deep crust and mantle structures (Chen et al. 1996; Nelson et al. 1996; Becken et al. 2011; Yan et al. 2016; Dong et al. 2016; Le Pape et al. 2017; Sarafian et al. 2018; Kühn et al. 2018).

However, many studies which are based on the inversion of electromagnetic data have ignored a key factor that is to evaluate the uncertainty and resolution of the preferred inversion model. In inversion problems, an infinite number of equivalent models exist that can explain the electromagnetic data to within a given misfit threshold. This is caused by the limited data coverage in time (or frequency) and space, the inevitable data noise and the strongly nonlinear relationship of data and model. The preferred inversion solution is only one of an infinitely large set of candidate models. In inversion, we need first establish a cost function which measures the data misfit between measurements and responses calculated by an approximation of the underlying physics. The responses of this physical system are computed based on a model parameterisation of the underground conductivity structure. Then, deterministic iterative (i.e. linearised) or stochastic inversion algorithms (Parker 1994; Zhdanov 2002; Tarantola 2005; Aster et al. 2012; Menke 2012) are employed to find a possible model which minimises the cost function to a certain level. The topography of the cost function measuring the data misfit may have an infinite number of local minima (valleys) and local maxima (hills) (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2012; Fernández-Martínez 2015). The preferred inversion model can locate at the bottom point of any such valley. A serious problem is that the valley containing this preferred inversion model may not include the geologically meaningful true model. To shorten the distance of the inversion model to the unknown true model or to make the inversion model locate in the same valley as the true model, a constraint or a reference point, such as a Tikhonov regularisation point (Jackson 1979; Tikhonov et al. 1995), must be fixed in this valley, which is implemented by adding a model regularisation term to the cost function. The preferred inversion model and the true model generally do not locate at the same point, because the bottom of this valley generally looks like an extended and distorted saddle shape. The distance of the preferred inversion model to the true model (resolution) and its possible variations (uncertainty) can be appraised using linearised or nonlinear model analysis.

Linearised model analysis tools can offer quantitative measures for both resolution and uncertainty of the preferred inversion model. A quantitative measure of model resolution can be computed in form of the model resolution matrix. Quantitative measures of model uncertainty can be computed in terms of the model covariance matrix (Backus and Gilbert 1968), and equivalent model domains can be calculated using the partially nonlinear concept of pseudo-hyperellipsoids (Johansen 1977; Kalscheuer and Pedersen 2007; Kalscheuer et al. 2010). Formally, the preferred inversion model is a sum of the true model weighted with the resolution matrix, the reference model (if applicable) weighted with the complement of the resolution matrix and the noise in the measurements weighted by the generalised inverse (Friedel 2003; Günther 2004; Kalscheuer et al. 2010). Hence, the model resolution matrix is considered a blurring filter through which we see the contribution of the true model in the inversion model. The model covariance matrix describes how uncertainties in the true model, the reference model and the data translate into uncertainties of the inversion model. It can be safely assumed that the uncertainty in the true model is zero. If no reference model is used (e.g., in a smoothness-constrained inversion) or if the reference model is not associated with uncertainty, the only uncertainty projecting into the uncertainty of the inversion model is that of the field data. It is valuable to mention another quantitative measure of model uncertainty in terms of funnel functions (Oldenburg 1983; Menke 2012). In this approach, the upper and lower bounds of the model parameters (or the local averages of model parameters) for both linear and nonlinear optimisation problems are estimated. Subsequently, model parameter uncertainties are computed as differences between these estimated upper and lower bounds.

Whereas linearised model analysis tools estimate model uncertainty and resolution using exactly the same data, data uncertainties and model constraints that were used to compute the inversion model, nonlinear model analysis tools do not only account for the nonlinearity of the forward problem but utilise the fact that the preferred inversion model reflects changes in data, data uncertainties and model constraints (initial model, reference model, smoothness constraint, structural and petrophysical constraints). Therefore, in these nonlinear methods, the equivalent model domain of the preferred inversion model is generated by varying the data set (Schnaidt and Heinson 2015), the data uncertainties (Li et al. 2009), the initial model (Bai and Meju 2003; Schmoldt et al. 2014), the reference model (such as methods computing depth-of-investigation indices, in short DOI indices, e.g., Oldenburg and Li 1999; Oldenborger et al. 2007), the regularisation (or smoothness) operators (Constable et al. 1987; de Groot-Hedlin and Constable 1990, 2004; Kalscheuer et al. 2007), and, if applicable, the structural or petrophysical model constraints (Gallardo and Meju 2004; Shamsipour et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2012; Kamm et al. 2015; Giraud et al. 2017, 2019). Only models with responses that agree with the field data to within an acceptable data misfit threshold are accepted as equivalent models. In its most simplistic form, nonlinear model analysis is based on the generation of equivalent models by manually applying changes to the preferred inversion model and evaluating the data fit or running inversions in which the resistivities of the modified cells are fixed (Becken et al. 2008; Thiel et al. 2009; Thiel and Heinson 2010; Juanatey et al. 2013; Dong et al. 2014; Lindau and Becken 2018). In addition, further nonlinear model analysis approaches generate equivalent models by globally or stochastically searching the model domain (Tarantola 2005). Compared to the linearised model analysis tool, where its equivalent models are more or less in the vicinity of the preferred inversion model, most approaches to nonlinear model analysis explore a larger part of the model domain. However, we should keep in mind that most currently available methods of nonlinear model analysis do not offer information on model resolution, and many offer only qualitative appraisals of model uncertainty. With regard to model uncertainty, this is so, because most nonlinear schemes do not enforce convergence to a particular target misfit. However, in linear inversion theory, model parameter uncertainties corresponding to a 68 % confidence level are associated with a misfit deviation of 1.0 from the misfit of the optimal model. Hence, using the simplistic approach mentioned above, the stability of a large-scale target structure with a pronounced resistivity contrast to the background medium can be grossly evaluated, and in many practical applications this approach is fully sufficient. However, in applications where targets are associated with comparatively small resistivity contrasts, e.g., tracing a contaminant plume through an aquifer, the acceptable levels of model uncertainty are small. Hence, it is important to calculate quantitative estimates of model uncertainty controlling misfit changes stringently. Furthermore, since EM inversion problems are nonlinear, extreme model parameters may not correspond to confidence levels of 68 %, even though the extreme models have misfit deviations of 1.0. Hence, a comprehensive stochastic analysis of the model space may be necessary.

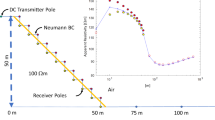

With the above linearised and nonlinear model analysis tools, we are able to estimate model uncertainty and/or resolution. Considering the uncertainty estimates, we can establish confidence levels for the various structures observed in the preferred inversion model (Fig. 1). Those parts of a model space that have low uncertainties and resolution matrix entries with little spread around the main diagonal might be used for assisting the geological interpretation or the design of drilling campaigns. In addition, using the guideline that the preferred inversion model should have adequately good resolution and small ranges of uncertainties, we can apply the results of model analysis to inversely optimise the acquisition layout (Fig. 1) or the inversion grid. Optimal survey configurations can help us to collect minimum sets of electromagnetic data, which lead to adequate constraints for the target structures, cost-effective surveys (Roux and Garcia 2014) and reduced computational loads of inversions (Yang and Oldenburg 2016).

In this review, we will first comprehensively introduce the basic theory and methodologies of linearised and nonlinear model analysis. Second, practical computational strategies are presented to accelerate the computation of linearised model uncertainty and resolution estimates. Third, applications using model analysis to appraise the preferred inversion model are summarised. Fourth, we discuss the developments in using model analysis as tools to design optimal survey configurations and inversion grids. Fifth, we conclude this paper with general recommendations both on inversion and model analysis and an outlook on future research directions.

2 Methods of Model Analysis

The conductivity distribution of the Earth is discretised into an inversion grid \({\mathbb {G}}\) and an associated model vector \({\mathbf {m}}\) (where \({\mathbf {m}}\) is generally a logarithmic function of conductivity). Assuming there are M elements or cells in the inversion grid, the size of the model vector is M. The underlying physical system is controlled by Maxwell’s equations (Nabighian 1991; Berdichevsky and Dmitriev 2008; Chave and Jones 2012), and it is denoted by the forward operator \({\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbb {G}}, {\mathbf {m}}\right]\) (henceforth, in short \({\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}\right]\)). The measured electromagnetic responses such as scalar and tensor impedances (Lilley 2017) at receivers are arranged into an observation data vector \({\mathbf {d}}\) of size N, where N is the number of measurements. The electromagnetic responses can be acquired on the ground, from aircraft, in the ocean and even in boreholes. Uncertainties generally exist in the measured data set due to slight perturbations in the geometric sensor layout, intrinsic noise in the sensors, amplifiers and analogue-to-digital converters and ambient electromagnetic noise, which may behave like random variables with zero mean or lead to a systematic bias away from the true signal. In most cases, we assume that the uncertainty \(\delta _{i}\), \(i=1,\ldots ,N\) in each observation originates from random noise with a normally distributed probability of zero mean and nonzero standard deviation. Then, we design a data misfit term \(Q_{\mathrm{d}}\) by measuring the difference between the observations and the predicted responses for an as yet to be determined model vector \({\mathbf {m}}\), that is (Abubakar et al. 2009; Menke 2012; Aster et al. 2012):

where the weighting matrix \({\mathbf {W}}_{d}\) is diagonal, \({W}_{d}^{ii}= 1/\delta _{i}\), \(i=1,\ldots ,N\), and makes the data misfit dimensionless. Superscript T denotes vector or matrix transposition. Now, the weighted data misfit describes a \(\chi ^{2}\)-distribution with an expectation value of N. Typically, \(Q_d\) is expressed as a root-mean-squared fit \(\text {RMS} = \sqrt{Q_d/N}\) of the forward responses to the field measurements.

In the hyperdimensional \(Q_{\mathrm{d}}-{\mathbf {m}}\) plot, infinite numbers of valley and hills exist (Snieder 1998). Unless there are profound misconceptions (e.g., model dimensionality, anisotropic or frequency-dependent material parameters), the true model, which can be considered a simplified form of the real Earth, can be assumed to be in one specific valley. Our purpose of inversion is to try to come close to this unique true model using the information from the observation data \({\mathbf {d}}\). However, due to data uncertainty, the limited data coverage, and the inherent nonlinear characteristics and fundamental equivalences of the underlying physical system, the inversion problem cannot be solved ad hoc, and meaningful solution approaches depend on the particular properties of the given inversion problem (Menke 2012). To this end, we categorise inversion problems following Menke (2012):

In purely under-determined inversion problems, there is not enough information in the data to uniquely determine a single model parameter. Formally, cases with \(M>N\) may qualify for being under-determined. However, depending on the information content in the data, even cases with \(M<N\) may be under-determined. Under-determined inversion problems have model solutions with zero prediction error, i.e. \(Q_d = 0\).

In contrast to the previous category, over-determined inversion problems are characterised by the fact that all model parameters are uniquely determined, and \(M<N\) is a necessary, but not a sufficient formal requirement. Over-determined inversion problems have solutions with \(Q_d > 0\).

In even-determined inversion problems, all model parameters are uniquely determined by the data, \(M=N\), and \(Q_d = 0\).

Mixed-determined inversion problems are the most general case. Here, parts of the model domain are over-determined, whereas other parts are under-determined. 2D and 3D geophysical inversion models are typically mixed-determined, and we will predominantly consider problems that fall into this category.

Under- and mixed-determined inversion problems are by definition non-unique (Miensopust 2017). One remedy to this non-uniqueness problem is to introduce additional model constraints or model regularisation (Jackson 1979; Tikhonov et al. 1995; Zhdanov 2002; Menke 2012). The model constraints can enforce the conductivity distribution to vary smoothly (Constable et al. 1987; de Groot-Hedlin and Constable 1990; Kalscheuer et al. 2010), they can include prior geological knowledge, restrict the conductivity distribution by rock sampling tests, or be based on structural constraints (Gallardo and Meju 2011; Yan et al. 2017b) and petrophysical constraints (Moorkamp 2017; Haber and Holtzman Gazit 2013) using information offered by other geophysical data sets (such as seismic, gravity, magnetic and logging data). Using a properly designed model constraint, the inversion algorithm can converge to a model that is close to the true model. Therefore, to obtain a geologically meaningful model close to the true one, it is inevitable to enforce model constraints, which is accomplished by designing a model misfit term (typically in form of a quadratic functional) which measures the distance from the inversion model to the reference model \({\mathbf {m}}_{r}\), as (Abubakar et al. 2009; Menke 2012; Aster et al. 2012):

where the weighting matrix \({\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\) contains either purely mathematical operators to enforce model smoothness or accounts for geological or geophysical constraints (Constable et al. 1987; Zhdanov 2002). Then, these two misfit terms in form of quadratic functionals can be assembled into one single cost function Q:

where the weighting factor or trade-off parameter \(\alpha >0\) balances the contribution of the data misfit term \(Q_{\mathrm{d}}\) and the model misfit term \(Q_{\mathrm{m}}\) in the cost function Q.

It is a standard choice in the geo-electromagnetic induction community to minimise the above \(l_2\)-norm variant of the cost function Q (Menke 2012; Aster et al. 2012; Farquharson and Oldenburg 2004; Krakauer et al. 2004; Schwarzbach and Haber 2013; Usui 2015; Mojica and Bassrei 2015; Jahandari and Farquharson 2017; Wang et al. 2018a). However, it may be desirable to use general \(l_p\) norms instead. To obtain more robustness against data outliers and more compact anomalies, for instance, the \(l_1\) norm may be used. General \(l_p\) norms can be conveniently implemented in a least-squares algorithm using re-weighting matrices that are adjusted in each iteration. This technique is generally known as iteratively re-weighted least-squares (IRLS) and has been occasionally used in electromagnetic geophysics (e.g., Farquharson and Oldenburg 1998; Oldenburg and Li 2005; Rosas-Carbajal et al. 2012). However, we are not aware of any work, where formal model uncertainty and resolution estimates were derived for an IRLS algorithm.

2.1 Linearised Model Analysis

Since the forward operator in electromagnetic problems is a nonlinear operator with respect to the model parameters, the data misfit function \(Q_{\mathrm{d}}\) will generally vary with the model parameters with larger than quadratic order. This means that the hyperdimensional \(Q_{\mathrm{d}}-{\mathbf {m}}\) plot may have multiple side lobes with local minima or a (possibly large) number of equivalent global minima. To transform the misfit function Q to a quadratic one for which a solution to the optimisation problem can easily be found, the nonlinear forward operator of the model \({\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\) of the \(k+1\)-th iteration is expanded to first-order around the model \({\mathbf {m}}^{k}\) of the kth iteration using a Taylor series:

where \({\mathbf {J}}\) is the sensitivity matrix or the Jacobian matrix at the kth iteration. Substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (3), we get an approximation to the cost function that is quadratic in model \({\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\). Minimising this quadratic cost function, we get an iterative formula to calculate the \(k+1\)-th model (Siripunvaraporn and Egbert 2000; Kalscheuer et al. 2010; Menke 2012):

where \({\mathbf {J}}_{w}^{-g} = \left[ {\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}+\alpha {\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\right] ^{-1}{\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}\) is the generalised inverse matrix, and \(\hat{{\mathbf {d}}}^{k}={\mathbf {d}}-{\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}^{k}\right] +{\mathbf {J}}\left( {\mathbf {m}}^{k}-{\mathbf {m}}_{r}\right)\) was used.

If model \({\mathbf {m}}^{k}\) is linearly close to the true model \({\mathbf {m}}_{\mathrm{true}}\), we get (Friedel 2003; Kalscheuer et al. 2010)

and, hence,

where \({\mathbf {n}}\) denotes the data noise. Substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (5), we get

where \({\mathbf {R}}_{\mathrm{M}}={\mathbf {J}}_{w}^{-g}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}\) is defined as the model resolution matrix. It indicates the distance from the inverted model to the unknown true model. If we assume that at iteration \(k+1\) the inversion terminates, then \({\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\) can be considered as the preferred inversion model. Equation (7) shows that this preferred inversion model consists of contributions by the true model, the reference model and the data noise. If the resolution matrix \({\mathbf {R}}_{\mathrm{M}}\) is an identity matrix, the preferred inversion model is said to be perfectly resolved and does not depend on the reference model. It is equal to the sum of the true solution and the noise in the data weighted with the generalised inverse. In the opposite case with poor model resolution, the preferred inversion model consists mostly of the reference model. For a given data set, the resolution properties of the preferred model depend strongly on the trade-off parameter \(\alpha\) (which is contained in \({\mathbf {J}}_{w}^{-g} = \left[ {\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}+\alpha {\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\right] ^{-1}{\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}\) and Eq. 3). Going to a smaller value of the trade-off parameter, the resolution matrix will come closer to the identity matrix, as long as the generalise inverse still exists, i.e. \({\mathbf {R}}_{\mathrm{M}} \rightarrow [{\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}]^{-1}{\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T} {\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}={\mathbf {I}}\) as \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\). At the same time, the generalised inverse \({\mathbf {J}}_{w}^{-g}\) will become very large in amplitude as \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\) such that the noise term is amplified. In the opposite case, when the trade-off parameter is set to a very large value, the nonzero entries of the resolution matrix will become more spread around the diagonal of the resolution matrix, meaning poorer resolution, but the noise contribution will be smaller. In the first case, we retrieve a well-resolved but unstable model. In the second case, we retrieve a stable, but poorly resolved model. Both of these extreme cases are far from optimal, and it is clear that a compromise needs to be made when it comes to the choice of trade-off parameters. Formally, this trade-off between model resolution and stability is explored by plotting the spread of the resolution matrix versus the size of the model covariance matrix (see below) for a large range of trade-off parameters (Hansen 1992). The only options that we have to obtain a more favourable trade-off curve is to add more measurements which should shift the whole trade-off curve to the better or to employ additional geo-scientific information in the reference model \({\mathbf {m}}_{r}\) or the model regularisation operator \({\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\).

The model resolution matrix \({\mathbf {R}}_{\mathrm{M}}\) can be rewritten as

where \({\mathbf {a}}^{i}\) and \({\mathbf {b}}^{i}\) denote the ith row and column resolution vectors, respectively, for \(i=1,\ldots ,M\). The row vector \({\mathbf {a}}^{i}\) acts as a linear projection of the true model to the ith inversion model parameter (see Fig. 2), which is referred to as the averaging function, or upon normalisation by the areas or volumes of all cells, as the resolving kernel (see Fig. 3, effectively a resolution density). The concept of averaging functions were originally presented by Backus and Gilbert (1968). The column resolution vector \({\mathbf {b}}^{i}\) describes how a delta-like perturbation in the ith true model parameter spreads over the inversion model vector and is generally referred to as the point-spread function (Alumbaugh and Newman 2000). The ideal shape of both the averaging function and the point-spread function is a delta function which has the only nonzero value (a unit value) on the diagonal entry of the model resolution matrix, i.e. at the target model parameter (see Fig. 3). There are two definitions for unimodularity of a given resolving kernel. In the first definition, unimodularity means that the resolving kernel has a single main lobe without any positively or negatively valued side lobes. In the second definition, unimodularity refers to the 2D or 3D integrals of the resolving kernel over the areas or volumes of all model cells evaluating to one (e.g., Ory and Pratt 1995). In the latter case, there is no bias in the form of an average amplitude shift from the true model (Treitel and Lines 1982).

Conceptual model resolution matrix with the averaging function (\({\mathbf {a}}^{i}\)) and point-spread function (\({\mathbf {b}}^{i}\)), \({\mathbf {m}}_{\mathrm{true}}\) is the true (unknown) model, \(m^{k+1}_i\) is the ith component of model vector \({\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\) obtained at the \(k+1\)-th inversion iteration, and \({m}_{true,i}\) is the ith component of the true model vector

Conceptual resolving kernels for model parameters with nearly perfect (a) and poor (b) resolution. Positive and negative side lobes, an offset of the main lobe from the position of the investigated parameter on the diagonal (dashed line) and a large spread of the resolving kernel are characteristics of poor resolution

The model resolution matrix only indicates how close the preferred inversion model is to the true model. It is incapable of estimating the range of all candidate models or equivalent models which all fit the cost function Q equally well to within a certain threshold or, conversely, how uncertainty in the measurements translates to uncertainty in the model parameters. The (a posteriori) model covariance matrix gives us a quantitative measure of how uncertainty in the true model, the reference model and the data propagates into model uncertainty. Using Eq. (7), the (a posteriori) model covariance matrix \({\mathbf {C}}\) for the \(k+1\)th model (the preferred inversion model) is computed as (Menke 2012):

where \(E\left[ \cdot \right]\) is the statistical expectation operator. Hence,

where we assume that there is no variability in the true model (\(\left[ cov\,{\mathbf {m}}_{\mathrm{true}}\right] =0\)) and that the covariance of data noise \(\left[ cov\,{\mathbf {n}}\right]\) was correctly identified in the data weighting matrix such that \({\mathbf {W}}_{d}\left[ cov\,{\mathbf {n}}\right] {\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}={\mathbf {I}}\), i.e. \(\left[ cov\,{\mathbf {n}}\right] = {(\delta _{i})}^{2}\) (\(i=1,\ldots ,N\)) when only variances are accounted for. As for actual field data sets, the true mean values and covariance structure of data noise are rarely known. In particular, mean values of data noise deviating from zero represent systematic noise and may lead to pronounced artefacts in inversion models, because the mean values of data noise are assumed to be zero in inversion. If the covariance of the reference model can be expressed as \(\left[ cov\,{\mathbf {m}}_{r}\right] = \left( \alpha {\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\right) ^{-1}\), we have \({\mathbf {C}} = \left[ {\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}+\alpha {\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\right] ^{-1}\). If the reference model is considered a fixed vector (implying that \(\left[ cov\,{\mathbf {m}}_{r}\right] = {\mathbf {0}}\)) or zero as in some deterministic inversion schemes (such as the Occam inversion; Constable et al. 1987), we have:

Both the model resolution matrix and the model covariance matrix are of size \(M\times M\), where M is the number of model parameters, and symmetric. For 2D inversion problems, storage and direct computation of the generalised inverse matrix \({\mathbf {J}}_{w}^{-g} = \left[ {\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}+\alpha {\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\right] ^{-1}{\mathbf {J}}^{T}{\mathbf {W}}_{d}^{T}\) as well as the model resolution and covariance matrices is not a problem on modern computer systems. However, for 3D problems with large values of M it will be difficult to store and directly compute the generalised inverse matrix \({\mathbf {J}}_{w}^{-g}\), the model resolution matrix and the model covariance matrix.

Using a Taylor series expansion of the forward model response \({\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\right]\) around that of the model of the kth iteration and substitution of Eq. (5) for the preferred model \({\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\) (iteration \(k+1\)), the predicted data \({\mathbf {d}}^{k+1,pre}\) (equalling the model responses \({\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\right]\)) can be related to the measured data \({\mathbf {d}}\) (Friedel 2003; Kalscheuer et al. 2010; Menke 2012):

Here, the data resolution matrix\({\mathbf {R}}_D = {\mathbf {J}}{\mathbf {J}}^{-g}_{w}{\mathbf {W}}_d\) can be thought of as a set of blurring filters (rows) through which the field data \({\mathbf {d}}\) are reproduced in the predicted data \({\mathbf {d}}^{k+1,pre}\). In the more general case of a mixed-determined inversion problem, but also for an over-determined problem, the model responses \({\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}^{k+1}\right]\) consist of terms related to the field data and the responses of the model of the kth iteration and of the reference model. If the response of the model of the kth iteration was linearly close to that of the reference model, Eq. (12) would further simplify to \({\mathbf {d}}^{k+1,pre} \approx {\mathbf {R}}_D{\mathbf {d}} + \left( {\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {R}}_D\right) {\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}_r\right]\). In the case of an under-determined inversion problem, \({\mathbf {R}}_D = {\mathbf {I}}\) leading to perfect data fit \({\mathbf {d}}^{k+1,pre}={\mathbf {d}}\). The diagonal elements of \({\mathbf {R}}_D\) indicate how much relevance a given measurement has in its own forward response or prediction. Hence, the diagonal elements are typically referred to as data importances. Data importances play an important role in some approaches to optimal survey design (see below).

The singular value decomposition (SVD, Hansen 1990) technique is widely used to approximate the weighted sensitivity matrix \({\mathbf {J}}_{d}={\mathbf {W}}_{d}{\mathbf {J}}\). Using a threshold (trade-off) value for the minimum permissible singular value, all contributions with singular values smaller than the threshold singular value are dropped, or, alternatively, all singular values are damped. The concept of using the SVD technique to accelerate the computation of resolution and covariance matrices was initially proposed for 1D inversion problems by several pioneers (Gilbert 1971; Wiggins 1972; Jupp and Vozoff 1975; Lines and Treitel 1984). To determine the truncation level, there are various different techniques (see below). One particular technique selects the truncation level or damping factor, such that the so-called mean-square error (MSE) is minimised (Shomali et al. 2002; Pedersen 2004; Plattner and Simons 2017). The mean-square error is defined as the sum of the model variances (trace of the a posteriori model covariance matrix) and the model bias squared (in SVD terms, the null-space projection squared). Essentially, the null-space projection in the latter term can be considered the complement \({\mathbf {I}}-{\mathbf {R}}_p\) of the model resolution matrix \({\mathbf {R}}_p\) for truncation level p. Hence, the mean-square error describes the trade-off between the size (trace) of the model covariance matrix and the spread of the model resolution matrix. Whereas the first term (sum of model variances) increases with increasing truncation level p, the second term (spread of resolution matrix) decreases with increasing p. Hence, the mean-square error attains its minimum at a specific p.

Using the standard SVD technique, it is impossible to consider the effect of the model constraint or model regularisation term. Therefore, to be capable of including the effects of model constraints in model resolution and covariance matrices, the generalised singular value decomposition (GSVD) technique (Christensen-Dalsgaard et al. 1993; Golub and Van Loan 2012) is presented here. Using the GSVD technique, the weighted sensitivity matrix \({\mathbf {J}}_{d}\) and the model regularisation matrix \({\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\) are simultaneously decomposed as follows:

Here, the sizes of the orthogonal matrices \({\mathbf {U}}_{1}\) and \({\mathbf {U}}_{2}\) are \(N\times N\) and \(M\times M\), respectively, and the columns of \({\mathbf {U}}_{1}\) and \({\mathbf {U}}_{2}\) are the generalised left singular vectors (eigenvectors spanning data and model constraint spaces, respectively). Matrix \({\mathbf {V}}\) is orthogonal and of size \(M\times M\), and its columns are the generalised right singular vectors (eigenvectors spanning model space). The diagonal matrices \({\varvec{\varLambda }}_{1}\) and \({\varvec{\varLambda }}_{2}\) contain N and Msingular values\(\lambda _{1}^{i}\) (\(i=1,\ldots ,N\)) and \(\lambda _{2}^{j}\) (\(j=1,\ldots ,M\)) on their diagonals, respectively. Substituting Eqs. (13) and (14) into the generalised inverse \({\mathbf {J}}_{w}^{-g}\), we have:

Now, the model resolution matrix in Eq. (7) becomes

Using Eqs. (11) and (15), the model covariance matrix is

After the inversion procedure has converged, we can employ the above techniques to compute the model resolution and covariance matrices of the resulting preferred inversion model. The model covariance matrix defines an equivalent model domain for the preferred inversion model. However, we should keep in mind that the thus computed resolution and covariance matrices \({\mathbf {R}}_{\mathrm{M}}\) and \({\mathbf {C}}\) (Ogawa et al. 1999) only indicate local and linearised estimates of the reliability of the preferred model as an approximation to the true model, as the assumption that the converged model should be linearly close to the unknown true model is used. Therefore, the above procedure is also named as linearised model analysis. Based on this discussion of linearised model analysis, we describe the general effects of varying data quality, model discretisation and model regularisation on model uncertainty and resolution estimates. We note that the general trends and patterns described below will also be found in nonlinear analyses described in later sections.

2.1.1 Effects of Data Quality on Model Uncertainty and Resolution

For subsequent inversion to be meaningful, it is of vital importance to estimate data with reliable statistical uncertainty during processing and to identify and remove data with systematic noise. Depending on the measurement methodology, the retrieved numbers of samples may not allow for representative data uncertainty to be estimated. In passive methods, such as magnetotellurics, long (days to weeks) time series are recorded to increase the number of samples, and advanced time-series processing routines are robust with regard to outliers (Egbert 1997; Ritter et al. 1998; Smirnov 2003; Garcia and Jones 2008; Chave 2017). Hence, one may argue that the estimated uncertainties of MT data are meaningful. In modern controlled-source electromagnetic methods, the options for data processing are similarly advanced as in magnetotellurics (e.g., Pankratov and Geraskin 2010; Streich et al. 2013). In some active methods, one may resort to reciprocal measurements (Parasnis 1988) to have a gross handle on data control, data editing and data uncertainty. In fact, this is a standard approach in geoelectrics, where modern multi-channel data loggers can optionally record measurements from reciprocal electrode configurations. For these methods, we note that assignment of uncertainty floors and data editing are subjective choices strongly depending on the interpreter’s experience. With more simplistic equipment, assumptions about data quality and uncertainty are even more subjective.

Increasing data uncertainty floors means that the acceptable ranges of forward responses and with that the acceptable ranges of model parameters generally increase. However, model regularisation counteracts strong model variability. Thus, when the target RMS (typical value of one) is not changed after increasing uncertainty floors, the trade-off parameter is often increased such that the variability of the model parameter with position in model space may be lower than for a lower uncertainty floor. In turn, this leads to increased spreads of resolving kernels, whereas the parameter uncertainties may show little change. As evident from Eqs. (10) and (11), a partial increase of model parameter uncertainties owing to an increased data uncertainty floor is, to some extent, counterbalanced by the increased trade-off parameter. Note the exact behaviour will depend on the particular choice of model regularisation and trade-off parameter and whether the increase in data uncertainty floor is balanced by a corresponding increase in the trade-off parameter.

Any systematic noise (e.g., from source effects of infrastructure, buried cables, insufficient system calibration) remaining after data editing may generate artefacts in inversion models. Depending on how strongly the data deviate from their nominal values without systematic noise, the associated model parameters may be biased quite heavily into the wrong direction generating artefactual model structures with high sensitivity and seemingly good model resolution.

2.1.2 Effects of Model Discretisation on Model Uncertainty and Resolution

The model resolution, model covariance and data resolution matrices depend strongly upon model discretisation. In the limiting cases, there may be too many model parameters for even a single parameter to be uniquely determined (i.e. the under-determined case), or there may be too few parameters in an over-determined inversion problem to explain the given data adequately. In the former case, model resolution is poor, but data resolution is perfect. In the latter case, model resolution is perfect, but poor data fit makes the model meaningless. Hence, the number of model parameters needs to be increased to the point where data fit becomes acceptable and model resolution is still good. Increasing the number of model parameters may render a previously over-determined inversion problem mixed-determined leading to increased model uncertainty and deteriorated resolution (e.g., Kalscheuer et al. 2015). Similar effects are observed when the number of model parameters is increased turning a mixed-determined problem to an under-determined problem. In the mixed- and under-determined 2D and 3D inversion problems that we are concerned with here, one may argue that regions with focused model resolution should be further refined, if measurements with high sensitivities to these model regions have too high misfit (see below). Similarly, one may argue that the inversion grid should be coarsened in model regions with poor resolution to make the inversion problem more economic. If the model was discretised sufficiently to explain a given data set, one might argue that further refinement of the inversion model should not lead to significant changes in model structure, other than smoother transitions, given the refinement was balanced by a corresponding adjustment in model regularisation. Clearly, such refinement will lead the nonzero entries in the model resolution matrix to be spread over a correspondingly larger number of cells. Despite such rather profound changes in the model resolution matrices, there will be little change in the resolving kernels beyond a certain level of discretisation. This is simply so, because resolving kernels can be thought of as resolution densities that approach there continuous limits with advancing refinement. Considering Eqs. (10) and (11), mesh refinement leads to decreased sensitivities and, with that, to an increase of the part of model parameter uncertainty related to the sensitivity matrix. However, mesh refinement is often accompanied by an increased trade-off parameter, possibly offsetting the increase in parameter uncertainty related to sensitivity. Note the exact behaviour will depend on whether Eq. (10) or Eq. (11) is used to compute uncertainties, the particular choice of model regularisation and whether the mesh refinement is balanced by a corresponding increase in the trade-off parameter. For instance, if Eq. (11) is used (i.e. uncertainty in the reference model is neglected), the effects of diminishing sensitivity will dominate leading to increasing model uncertainty with progressing refinement. In contrast, if (1) Eq. (10) is used (i.e. uncertainty in the reference model is accounted for), (2) the model regularisation matrix is regular, and (3) the trade-off parameter is increased, the model regularisation term may balance the effects of diminishing sensitivity with progressing refinement.

2.1.3 Effects of Model Regularisation on Model Uncertainty and Resolution

Often, we hardly have any prior knowledge and, hence, the model regularisation is based on ordinary smoothness constraints, where the adjustable parameters are the weights on horizontal and vertical smoothness, the order of the smoothness constraints and the type of the smoothness constraints (direct differences or spatial derivatives). Higher horizontal and vertical weights will lead to reduced vertical and horizontal spreads, respectively, of the resolving kernel. Certainly, if we use prior information in the form of a reference model or a model weighting matrix \({\mathbf {W}}_m\) that is not correct, this will bias the inversion model to a wrong solution. This means that both the model weighting matrix \({\mathbf {W}}_m\) and, if applicable, the reference model \({\mathbf {m}}_r\) should be judiciously selected. In particular, non-unimodular resolving kernels (here those that do not integrate to one) introduce systematic bias, as the non-unimodularity leads to an average amplitude shift of the model parameters (Treitel and Lines 1982; Ory and Pratt 1995). This non-unimodularity is a direct consequence of the choice of the regularisation operator. It was shown by Ory and Pratt (1995) that regular model constraints (i.e. a regular model weighting matrix \({\mathbf {W}}_m\) for which an inverse exists) introduce non-unimodularity, whereas singular first- or second-order smoothness constraints give unimodular resolving kernels. As a consequence, we advocate construction of a preferred inversion model using smoothness constraints with local modifications to account for known structural contrasts (e.g., Yan et al. 2017b), if applicable. Other types of regularisation may introduce unintended bias and, in the absence of compelling prior evidence, reference models should only be used for hypothesis testing. In case that both smoothness constraints and a reference model are used, the inversion will project structural boundaries in the reference model to the inversion model preserving the resistivity contrasts of the reference model. This becomes directly evident by considering the model regularisation in, for instance, a 1D inversion with first-order direct differences as smoothness constraints and a structural boundary in the reference model between cells j and \(j+1\). In this case, the corresponding term of the model misfit function attains its minimum, if

meaning the inversion tries to preserve the resistivity contrasts of the reference model in the inversion model. In model regions where the information in the reference model is less reliable, this effect may introduce artefacts (which in this case is undesirable bias) to the inversion model. In such cases, it is advisable to remove or reduce the strength of the smoothness constraints across structural boundaries in the reference model, to modify the reference model or to use separate regularisation terms for model smoothness and proximity to the reference model (i.e. model smallness involving a diagonal regularisation matrix, e.g., Loke 2001; Oldenburg and Li 2005; Yan et al. 2017a). Finally, we note that biasing the inverse model using well-established prior constraints (e.g., from borehole logs) may be the only meaningful approach to model construction when data coverage is sparse and/or data quality is low.

In probabilistic inversion schemes, the product \({\mathbf {W}}_m^T{\mathbf {W}}_m\) is nothing else but the a priori model covariance matrix. Thus, if the a priori variances and covariances are small in size, the resulting inversion model will be more tightly constrained than for larger a priori variances and covariances.

2.2 Partially Nonlinear Model Analysis

Now, we investigate the range of model variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) or models \({\mathbf {m}}\) (\({\mathbf {m}}= {\mathbf {m}}^{*} + \triangle {\mathbf {m}}\)) in the equivalent model domain around a preferred model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\) that corresponds to a maximum permissible variation \(\triangle Q\) of the cost function, i.e. \(Q \le Q_*+\triangle Q\) where \(Q_*\) is the value of the cost functional for \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\). Re-examining the cost function, we have

Using the linear approximation \({\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}^{*}+\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\right] \approx {\mathbf {F}}\left[ {\mathbf {m}}^{*}\right] +{\mathbf {J}}\left[{\mathbf {m}}^{*}\right]\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\), we get:

The condition of \(\nabla_{\mathbf{m}} Q\) vanishing at \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\), i.e. at \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}=0\), implies

Thus, we get

where

This formula tells us that the cost function is a quadratic function in the model variation \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) in the neighbourhood of the preferred model (Johansen 1977; Kitanidis 1996). Depending on the degree of nonlinearity in the forward problem, the cost function may have valley- and hill-like structures at larger distance (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2012).

Defining \(\triangle Q = Q({\mathbf {m}})-Q({\mathbf {m}}^{*})\), and using the GSVD results in Eqs. (13) and (14), we obtain:

where \({\mathbf {p}}={\mathbf {V}}^{T}\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) is the generalised (or transformed) model parameter vector in the space of matrix \({\mathbf {V}}\). (If we set either \({\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}={\mathbf {I}}\) or \(\alpha =0\), the above GSVD result is reduced to the SVD result.) If a threshold value for the minimum permissible singular value is used, the dimension of vector \({\mathbf {p}}\) will be much less than M. The relationship between \(\triangle Q\) and the vector \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) in Eq. 24 defines a hyperellipsoid that can be rewritten in terms of the transformed model parameters \({\mathbf {p}}\) as

where \(p_{i}\) is the ith generalised model parameter, \(s_{i}=\sqrt{ \triangle Q/\left( (\lambda _{1}^{i})^2+\alpha \cdot (\lambda _{2}^{i})^{2}\right) }\) is the length of the semi-axis along the ith column vector of \({\mathbf {V}}\) (or model eigenvector). The above formula defines a hyperellipsoidal domain of equivalence in which each model generates electromagnetic responses within a variation \(\triangle Q\) of the cost function value \(Q({\mathbf {m}}^{*})\) of the preferred model. If the inversion problem was linear, the choice \(\triangle Q=1\) would correspond to an equivalent model domain with a 68 % confidence level for the model parameters (Johansen 1977). However, for nonlinear inversion problems, the association of a given misfit variation with a confidence level is, at best, approximate (Kalscheuer and Pedersen 2007). Usage of the linear approximation to the forward operator \({\mathbf {F}}\) in Eq. (21) implies that the obtained equivalent model domain is still a result of linearisation. The linear approximation is evident by the equality of the semi-axes in the directions of both negative and positive model eigenvectors.

Due to the nonlinearity, the actual semi-axes along the negative and positive directions of the eigenvector can be different. Thus, as a first step that accounts for nonlinearity takes this inequality into account. Since the nonlinearity in directions other than those of the model eigenvectors is neglected, this procedure generalises the hyperellipsoid to a pseudo-hyperellipsoid (see Fig. 4 for an example of two model parameters). For a given misfit variation \(\triangle Q\), the lengths of the semi-axes are determined by the positions in model space where the pseudo-hyperellipsoid (black line) coincides with the true misfit surface (red line). The computation of the actual semi-axis can be formulated as finding the roots of the following equation (Johansen 1977; Kalscheuer and Pedersen 2007):

with \({\mathbf {m}}={\mathbf {m}}^{*}+s_{i}^{\pm }{\mathbf {v}}_{i}\), \(i=1,\ldots ,M\). Equation (26) is a function of typically higher than quadratic order in the nonlinear semi-axes \(s_{i}^{\pm }\), where \(s_{i}^{-}\) and \(s_{i}^{+}\) indicate the semi-axes along the negative and positive directions of model eigenvector \({\mathbf {v}}_{i}\), respectively (Fig. 4). The stronger the nonlinearity, the larger is the difference between the lengths of \(s_{i}^{-}\) and \(s_{i}^{+}\). For electrical resistance tomography (ERT) and magnetotelluric (MT) 2D inversion problems, Kalscheuer and Pedersen (2007) and Kalscheuer et al. (2010) demonstrated that the lengths of the linearised semi-axes and the nonlinear semi-axes differ strongly along those eigenvector associated with small singular values. This pseudo-hyperellipsoid spanned by the nonlinear semi-axes defines an equivalent model domain around the desired model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\) over which the condition of the cost function to vary by no more than \(\triangle Q\) is fulfilled more closely than by the hyperellipsoid stemming from a linear approximation. A large axis length means that dramatic model changes along this direction only lead to small variations of the cost function. If the axis has an infinite length, an infinite number of candidate models exists so that the model parameter is not constrained. In contrast, if the axis has a small length, small model changes lead to significant variations of the cost function, which implies that the parameter is well constrained (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2012). The concept of using the pseudo-hyperellipsoid to describe the nonlinear equivalent model domain was introduced by Johansen (1977) and Pedersen and Rasmussen (1989).

Conceptual misfit hypersurface (red line) defined by misfit deviation \(\triangle Q\) from misfit \(Q\left( {\mathbf {m}}^{*}\right)\) of a preferred model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\) for a model \({\mathbf {m}}=\left( m_1,m_2\right) ^T\) with two parameters. The pseudo-hyperellipsoid (black line) is described by the semi-axes \(s_1^+\), \(s_1^-\), \(s_2^+\) and \(s_2^-\) along the model eigenvectors and yields a first improvement in the description of nonlinear effects on model uncertainty (e.g., deviations of \(m_1^{{\rm min}}-m_{1}^{*}\) and \(m_1^{\mathrm{{\rm max}}}-m_{1}^{*}\) from \(m_{1}^{*}\)). In contrast, the most-squares inversion determines the de facto models with minimum (e.g., \(m_{1 {\rm true}}^{{\rm min}}\)) and maximum deviations (e.g., \(m_{1 {\rm true}}^{\mathrm{{\rm max}}}\))

For the jth model parameter, its minimum and maximum values (e.g., \(j=1\), \(m^{{\rm min}}_{1}\) and \(m^{\mathrm{{\rm max}}}_{1}\) in Fig. 4) on this pseudo-hyperellipsoidal approximation to the cost function can be estimated by locating the coincident points of this pseudo-hyperellipsoid and the hyperplane characterised by a normal vector \({\mathbf {w}}_{j}\) with \(w_{j,i}=\pm 1\) if \(j=i\) else \(w_{j,i}=0\) if \(j\ne i\). This requires the gradient of the cost function to be parallel to the normal vector \({\mathbf {w}}_{j}\), which implies the following relationship

where \(\triangle Q\) is given in Eq. (24), and \(e_{j}\) is an arbitrary scalar to be determined. Thus, Eq. (27) becomes (Johansen 1977)

where we set \(\varvec{\varLambda }_{1,2}= {\varvec{\varLambda }}_{1}^{T}{\varvec{\varLambda }}_{1}+\alpha {\varvec{\varLambda }}_{2}^{T}{\varvec{\varLambda }}_{2}\). Using Eqs. (23) and (26), we get

Now, we get the extreme model variation for the jth parameter as the jth component of

where \({\mathbf {b}}= \left[ {\mathbf {V}}\varvec{\varLambda }_{1,2}{\mathbf {V}}^{T}\right] ^{-1}{\mathbf {w}}_{j}\), and the diagonal values \(\sqrt{\frac{\triangle Q}{{\varLambda }_{1,2}^{ii}}}\) are systematically replaced by the nonlinear semi-axes \(s_{i}^{\pm }\) (for detail cf. Johansen 1977; Kalscheuer and Pedersen 2007). If \(w_{j,j}=-1\), the estimated parameter \(m_j^* + \triangle {m}_{j}\) is the extreme minimum value, otherwise if \(w_{j,j}=1\), it is the extreme maximum one. Performing the above procedure for all model parameters, we can obtain an extreme parameter set which is an equivalent model domain for which the cost function varies by no more than \(\triangle Q\). If the inversion problem was linear, the choice \(\triangle {Q}=1\) would yield extreme parameter sets with model parameter changes \(\triangle {m}_j\) that correspond to one standard deviation (see above). Note that this method takes the nonlinearity of the forward problems into account only through the nonlinear semi-axes along the model eigenvectors. Therefore, the above model uncertainty analysis is referred to as a partially nonlinear model analysis. In comparison with uncertainties estimated from linearised analysis (Eqs. 10 and 17), partially nonlinear model uncertainty estimates may give an indication on the severity of nonlinear effects. However, owing to the limitation of studying nonlinearity in the directions of model eigenvectors, uncertainty estimates from partially nonlinear model analysis may be far off those computed using methods that account for nonlinearity to a fuller extent, such as most-squares inversion (see below). For radio-magnetotelluric and geoelectric 2D inversion examples, Kalscheuer and Pedersen (2007) and Kalscheuer et al. (2010) found that, depending on the case, uncertainties estimated using most-squares inversion were 0.7 to 100 times the partially nonlinear model uncertainty estimates. Hence, even partially nonlinear model analysis may grossly underestimate model variability.

2.3 Nonlinear Model Analysis

We divide the available nonlinear model analyses into deterministic and stochastic approaches and discuss these in the following. In particular for the deterministic methods, we try to sort the methods into different categories. However, there is conceptual overlap between the methods and the categorisation is, to some extent, arbitrary.

2.3.1 Deterministic Methods

The equivalent models obtained by the above linearised or partially nonlinear model analysis tools operate solely in the vicinity of the preferred inversion model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\). To get more reliable estimates of the confidence levels of the model parameters, larger parts of the model domain need to be explored, involving nonlinear model analysis tools. Recalling the inversion procedure, the inversion solution depends on the data, the data weighting matrix (data uncertainties), the forward responses and their accuracy, the data misfit, the regularisation weighting factor, the initial model, the reference model, the model weighting matrix (model constraints), the model misfit and the value of the cost function. Therefore, considering different combinations of these factors, we can take different approaches to analyse the effects of nonlinearity. Typically, these approaches aim to find \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) around the preferred inversion model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\)

subject to variations of the data \(\triangle {\mathbf {d}}\), variations of data uncertainties \(\triangle {\mathbf {W}}_{d}\), different numerical errors in computed forward responses \(\triangle {\mathbf {F}}\), variations of data misfits \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}\), variations of trade-off factors \(\triangle \alpha\) , changes of initial models \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}^{0}\), changes of reference models \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}_{r}\), variations of model weighting matrices (e.g., smoothness constraints) \(\triangle {\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\), variations of model misfits \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}}\), and variations of values of cost functions \(\triangle Q\).

Generally, we only vary one parameter in Eq. (31) at a time and fix the other parameters. The various methods listed below explore different parts of the model space. Hence, it is meaningful to use different approaches to explore the equivalent domain more comprehensively. In particular, we need strategies which have the capability of jumping over local maxima in the cost function or traversing through possible valleys of the cost functional. No single method is guaranteed to have these properties. Again, this emphasises the need to consider different methods. As described in Sect. 2.2, deviations of a given model parameter from its value in the preferred model \({\mathbf {m}}^*\) by one standard deviation correspond to variations \(\triangle Q\) in the cost function or \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}\) in the data misfit (depending on the case) by a value of one. Thus, in exploring model uncertainty, models obtained by the various methods listed below should be compared and evaluated based on the actual variations \(\triangle Q\) or \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}\) from the values of the cost function \(Q\left( {\mathbf {m}}^*\right)\) or the data misfit \(Q_d\left( {\mathbf {m}}^*\right)\) for the preferred model \({\mathbf {m}}^*\). Except for the edgehog method and most-squares inversion, strict threshold values are often not applied to \(\triangle Q\) or \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}\). In some cases, e.g., when the data uncertainties are changed, a stringent comparison may not even be possible. There is also a trivial reason why model variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) derived by a comparison of different methods may not be consistent. Most researchers are used to consider RMS misfits (where \(\text {RMS}=\sqrt{Q_{\mathrm{d}}/N}\)) and do not translate deviations in RMS misfit back to misfit deviations \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}\). Eventually, it is also a decision made by the user as to what misfit deviation seems to be acceptable and meaningful for a given problem. However, it is important to note that different “equivalent” models should generally be compared based on their misfits and that model variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) for values of \(\triangle Q\) or \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}\) differing from one would even in close to linear cases not correspond to model uncertainties associated with 68 % confidence levels.

In the categories outlined above, these are the most commonly used methods:

Variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}^*\):

This approach builds on manual variation of the preferred inversion model. It is also loosely referred to as a nonlinear sensitivity test, because the forward responses of the modified model are computed to study the effect of model variation on data fit. Several model regions of particular geophysical or geological interest are selected. A set of new synthetic models is built by varying the resistivities or geometries of these selected areas. Using forward modelling, those synthetic models which generate acceptable data misfit (RMS) are treated as equivalent candidate models. Hence, models \({\mathbf {m}} = {\mathbf {m}}^{*}+\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\) that fulfil the condition

$$\begin{aligned} Q_{\mathrm{d}} ({\mathbf {m}}^{*}+\triangle {\mathbf {m}}) < Q_{\mathrm{d}}^{*}, \end{aligned}$$(32)are added to the equivalent model domain, where \(Q_{\mathrm{d}}^{*}\) is a threshold value for data misfit deemed acceptable. Compared to other uncertainty analysis tools, this tool may be the most economical tool as only several forward modelling computations are needed to evaluate the model variations (Nolasco et al. 1998; Hübert et al. 2009; Juanatey et al. 2013; Hübert et al. 2013). More advanced versions of this approach account for the fact that model parameters outside a given region of interest need to be adjusted to generate forward responses with sufficiently low misfit. Thus, the model parameters of the region of interest are kept fixed in an inversion where the remaining model parameters are allowed to change (Park and Mackie 2000; Hübert et al. 2009; Juanatey et al. 2013; Hübert et al. 2013). We also can generate equivalent models by inverting responses computed from these new synthetic models and contaminated with noise representative of the field conditions (Kühn et al. 2014; Haghighi et al. 2018; Attias et al. 2018).

Variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {d}}\):

Bootstrap re-sampling builds on randomly sampling a data set (population) K times and replacing L individual data points in each random sampling step. This makes it possible to calculate statistical properties in the form of averages and covariance matrices of these K data sets. In model analysis, this can be taken advantage of by computing K inversion models from these K data sets. For MT model analysis based on bootstrapping, Schnaidt and Heinson (2015) suggested to replace the complete impedance tensor by drawing from a Gaussian distribution in which the distribution mean and standard deviation are the actual measurement and its uncertainty, respectively. For appraisal of the model ensemble, two measures were introduced—one for the variability of cell wise model resistivities and one for the variability of model structures using the cell wise cross-gradient of two models. Schnaidt and Heinson (2015) emphasised that the bootstrapping method can be implemented without access to the source code of the inversion algorithm. The conceptual simplicity of the bootstrapping method is appealing. However, this comes at the cost of an increased computational load, as K full inversions need to be run. Generalised cross-validation (GCV, e.g., Aster et al. 2012) generates a suite of N different models by removing a certain number of data points at a time from the original data set and inverting the remaining data. These GCV-based modifications to the data set are used in order to identify a suitable Lagrange multiplier (see below). However, we are not aware of geo-electromagnetic examples where this sampling of the model space was used to appraise the preferred inversion model. Global seismological tomography problems often use travel time residuals with respect to the responses of a layered Earth model as input data to the inversion. The 2D or 3D model parameters are velocity perturbations to the layered background model. One of the approaches to model uncertainty analysis in global seismological tomography is to randomly redistribute the travel time residuals. Since the permuted residuals are assumed to correspond to pure noise, the resulting inverse solutions are considered representative of model uncertainty (Spakman and Nolet 1988; Bijwaard et al. 1998; Tryggvason et al. 2002). Typically, inversion models of several such permuted residual vectors are computed and the maximum velocity perturbations of the individual 2D or 3D cells are considered upper limits of model uncertainty. Note there is no direct analogue to this approach in electromagnetic methods, because we do not consider residuals.

Variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {W}}_{d}\):

Changes to the data uncertainties in matrix \({\mathbf {W}}_{d}\) or application of error (uncertainty) floors to the data uncertainties generate a set of alternative models \({\mathbf {m}}\) (\({\mathbf {m}}= {\mathbf {m}}^{*}+\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\)). Since models should be evaluated for equivalence based on their data fit and the uncertainties are changed, we prefer to refer to these models as alternative models rather than as equivalent models. We can first use an initial uncertainty level to obtain the preferred inversion model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\). Then, a set of other inversion models can be obtained by gradually adjusting uncertainty levels. As the uncertainty values are changed gradually, it can be expected that these newly generated model variations are around the preferred model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\). When the maximum level of data uncertainty is tested, the maximum level of model variation is obtained. Changing uncertainty levels is a natural idea to test the model variability (Li et al. 2009), as actual noise levels are generally unknown in real field data.

Variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {F}}\):

Over the last ten years, remarkable advances were made to decrease errors in the preferred inversion model caused by inaccurate approximations to the underlying physics. Improved forward modelling algorithms were developed to accurately include topographic effects using unstructured tetrahedral and hexahedral grids (Sambridge and Guðmundsson 1998; Ren and Tang 2010; Ansari and Farquharson 2014; Jahandari and Farquharson 2015; Yin et al. 2016; Cai et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017), to utilise accurate boundary conditions (Franke-Börner 2013), to employ accurate direct and iterative solvers for the resulting system of linear equations (Streich 2009; Kordy et al. 2016) and to adaptively refine the forward modelling mesh across pronounced contrasts in material parameters generating sharp changes in the electromagnetic field (Franke et al. 2007; Li and Pek 2008; Nam et al. 2010; Key and Ovall 2011; Schwarzbach et al. 2011; Ren et al. 2013; Ren and Tang 2014; Grayver and Kolev 2015; Ren et al. 2018). Therefore, we can ignore the effect of numerical errors of the approximation to the underlying physics, that is, \(\triangle {\mathbf {F}}\rightarrow 0\).

Variations \(\triangle \alpha\):

To obtain the optimal weighting factor \(\alpha\), we should follow the physically meaningful idea that a reasonable inversion procedure is to gradually add small or local-scale features into the large-scale or background model during the inversion iterations. We can start with a large value of the weighting factor so that the initial inversions reconstruct predominantly the large-scale structures of the model. During later iterations, the value of \(\alpha\) can be gradually decreased so that small-scale changes in the data misfit term become more important. Thus, small-scale structures or anomalies are added to the inversion model. This approach of gradually reducing \(\alpha\) is often referred to as a cooling procedure. Alternatively, we can automatically estimate an optimal weighting factor by using the so-called discrepancy principle (Constable et al. 1987; Siripunvaraporn and Egbert 2000; Kalscheuer et al. 2010), the L-curve technique (Hansen 1992) or the generalised cross-validation (GCV) method (Farquharson and Oldenburg 2004; MacCarthy et al. 2011). The discrepancy principle determines the optimal weighting factor by performing a line search and selecting the weighting factor that yields a model with a data misfit close to the target data misfit, i.e. a model that is commensurate with the level of noise assumed in the data. Using, the L-curve criterion, the L-shaped \(Q_{\mathrm{d}}-Q_{\mathrm{m}}\) curve plot is built by running inversions with different weighting factors. The point where the maximum curvature occurs and the data misfit is acceptable is chosen as the optimal weighting factor. The GCV method applies the leave-one-out (or leave-a-certain-number-out) methodology to the data set in order to establish a new function in which \(\alpha\) is its only variable. Then, an optimal value of \(\alpha\) is obtained by minimising this newly created function. Both the L-curve and the GCV techniques can effectively determine optimal values of the weighting factor \(\alpha\) (Farquharson and Oldenburg 2004; Krakauer et al. 2004; Mojica and Bassrei 2015). However, the GCV technique has a tendency of biasing the final value of \(\alpha\) to its initial value. Therefore, it is better to use cooling strategies together with the GCV technique in initial iterations such that the constraints from the model regularisation term are adequately considered, which is essential to stabilise the inversion and guarantee the preferred inversion model approaching the geologically meaningful true model (Farquharson and Oldenburg 2004; Krakauer et al. 2004; Schwarzbach and Haber 2013; Usui 2015; Mojica and Bassrei 2015; Jahandari and Farquharson 2017; Wang et al. 2018a). The above three methods of changing \(\alpha\) are routinely used in inversions to produce the preferred inversion model. With different weighting factors \(\alpha\) (including the optimal one), we can explore the model space a bit.

Variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}^{0}\):

Owing to the nonlinear nature of electromagnetic inversion problems, different initial models \({\mathbf {m}}^{0}\) lead to differences in the inversion result \({\mathbf {m}}^*\). Depending on the nature of the forward problem and the model regularisation, the differences may be more or less pronounced. By including a Marquardt–Levenberg damping term that regularises to the model of the previous iteration, for instance, the dependence of the preferred inversion model on the initial model may be quite strong. Thus, varying the initial model \({\mathbf {m}}^{0}\) is a fairly direct approach of constructing a limited domain of equivalent models (Bai and Meju 2003; Schmoldt et al. 2014).

Variations \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}_{r}\) and \(\triangle {\mathbf {W}}_{\mathrm{m}}\):

In the following, we concisely describe three nonlinear model analysis tools which are designed for this task. Approaches based on variation of model constraints try to explore larger parts of the model domain by using different reference models (Oldenburg and Li 1999; Oldenborger et al. 2007), different regularisation (smoothness) constraints (Constable et al. 1987; Kalscheuer et al. 2007) and structural or petrophysical constraints relating to models from other geo-scientific methods (Gallardo and Meju 2004; Meju 2009; Gallardo and Meju 2011; Gao et al. 2012; Giraud et al. 2017) . It needs to be noted that variations in the model constraints change the misfit function \(Q_m\) and, with that, Q in Eq. (3), such that direct comparisons of misfit values \(Q_m\) computed using different model regularisations are not meaningful. However, in the absence of compelling evidence from other geo-scientific methods that is included in \(Q_m\), we can argue that the typically employed smoothness constraints are a mathematical method to overcome the non-uniqueness of the inversion problem and that we may not be particularly interested in the actual values of \(Q_m\). Most inversion algorithms follow this line of thought implicitly by evaluating convergence purely based on RMS fit. If the inversion is run with different reference models \({\mathbf {m}}_r\) or model weighting matrices \({\mathbf {W}}_m\), the inversion models will locate in different regions of the model domain. Unless the RMS misfits are unacceptable, these inversion models should, at least in part, be close to the true model. This assumption is used to derive a depth-of-investigation (DOI) index for each model cell and was originally presented by Oldenburg and Li (1999). To analyse the model using DOI indices, we require two inversion models to compute a model quality measure vector \({\mathbf {D}}=\{D_{j},j=1,\ldots ,M\}\)

$$\begin{aligned} D_{j} = \frac{m_{j}^{1}-m_{j}^{2}}{m_{r,j}^{1}-m_{r,j}^{2}}, \end{aligned}$$(33)where \({\mathbf {m}}^{1}\) and \({\mathbf {m}}^{2}\) are two inversion models obtained using different reference models or constraints, in this case using different reference models \({\mathbf {m}}_{r}^{1}\) and \({\mathbf {m}}_{r}^{2}\). When \(D_{j}\) is close to zero, this suggests that the similarity in the inverted model parameters is caused by the data and, thus, that the jth model parameter is well resolved. The success of the DOI-based model analysis strongly depends on the experience of the users in trying different reference models. DOI indices can only be meaningfully computed for inversion models that have nearly identical RMS misfits. This is so, because systematic differences in data fit correspond to localised deviations between the inversion models. These localised deviations will falsely reflect in high DOI values, even though the model regions are well determined by the data. This means that the chosen model constraints are inappropriate in at least one of the inversions.

Variations \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}\) and \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}}\):

The Edgehog method (Jackson 1973) can be used to compute another larger equivalent model domain corresponding to a deviation \(\triangle Q\). It tries to generate the equivalent model domain \({\mathbf {m}}\) (\({\mathbf {m}}= {\mathbf {m}}*+\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\)) by using two inequality conditions \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}} \le \triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}^{*}\) and \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}} \le \triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}}^{*}\), where \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}+ \alpha \triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}} =\triangle Q\), and \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}^{*}\) and \(\triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}}^{*}\) are two threshold values for maximum deviations of data misfit and model misfit, respectively. To find \(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\), we need to solve the following two sub-problems:

$$\begin{aligned} \triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}} = \triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}^{*}\quad \text {and} \quad \triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}} \le \triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}}^{*}, \end{aligned}$$(34)and

$$\begin{aligned} \triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}} = \triangle Q_{\mathrm{m}}^{*}\quad \text {and} \quad \triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}} \le \triangle Q_{\mathrm{d}}^{*}. \end{aligned}$$(35)The equality condition above defines a closed hypersurface and the inequality condition defines a solid volume, that is, a hyperellipsoid in linear inversion problems. In the Edgehog method, the intersections of these hypersurfaces and closed volumes define the equivalent model domain. Compared to the most-squares method (see below), where the goal is to estimate model uncertainty by allowing for maximum variations of the cost function which is a sum of the data misfit and model misfit terms, the Edgehog method estimates the model uncertainty by individually considering the variations of either data misfit or model misfit. The Edgehog method was initially used in seismic problems (Lines and Treitel 1985). However, it is rarely used in geo-electromagnetic induction problems.

Variations \(\triangle Q\):

The most-squares method (Jackson 1976, 1979; Lines and Treitel 1985; Meju and Hutton 1992; Meju 1994, 2009; Kalscheuer and Pedersen 2007; Kalscheuer et al. 2010; Mackie et al. 2018) is generally used to compute a more representative equivalent model domain \({\mathbf {m}}\) (\({\mathbf {m}}= {\mathbf {m}}^{*}+\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\)) than that obtained by the partially nonlinear pseudo-hyperellipsoid technique. This equivalent model domain is constructed by identifying the extreme points of a scalar functional \({\mathbf {m}}^{T}{\mathbf {w}}\) subject to the requirement that the maximum allowed variations of objective function Q is \(\triangle Q\). This idea is formulated as:

$$\begin{aligned}&\text {minimise or maximise} \quad {\mathbf {m}}^{T}{\mathbf {w}} \nonumber \\&\text {subject to} \quad Q = Q({\mathbf {m}}^{*}) + \triangle Q, \end{aligned}$$(36)where \({\mathbf {w}}\) is a constant unit vector along the direction of a parameter or a parameter combination of interest, and \(Q({\mathbf {m}}^{*})\) is the value of the cost function at the preferred inversion model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\). Using a Lagrange multiplier \(\gamma\), Eq. (36) is transformed into a unconstrained optimisation problem. Its goal is to find the extreme model increments (\(\triangle {\mathbf {m}}\)) around the given minimum-misfit model \({\mathbf {m}}^{*}\), such that the cost functional