Abstract

In this paper we address the following question: is it more profitable, for an entrant in a differentiated market, to acquire an existing firm than to compete? We illustrate the answer by considering competition in the banking sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Nowadays, brand-image plays a role almost everywhere: in e-commerce where customers do not meet face-to-face merchants and thus use brand as a proxy for firms reliability, in fashion retail, where brand becomes social image, in food industry where brand can increase purchase confidence, inter alia.

Evidence that consumers value recognition is offered by Grossman and Shapiro (1988), who point out that consumers who buy a counterfeit Gucci or Coach product from street vendors typically know that the item is not an authentic Gucci or Coach product (and hence, not of the same quality). Nevertheless, such buyers are still willing to pay something for the forged name. Indeed, they would not likely buy the product without the forged brand name (Pepall and Richards 2002, p. 537).

In contrast to other banking activities, such as corporate banking directed at large business entities and private banking, providing wealth management services to high net worth individuals, retail banking is mainly a local business. Accordingly, our analysis cannot be extended to the other above business where brand awareness does not affect customers’ attitude toward the services provided and an international business dimension prevails.

In retail banking, a full service’ banking provides a complete bundle of retail products to consumers and small businesses. In the case of consumers, this bundle can embed not only current accounts and deposit accounts, but also credit products (e.g. mortgages or loans), savings products (e.g. investment funds) and insurance.

Quite interestingly, this solution seems to be preferred in service sectors where a personalized relationship matters (Norbäck and Persson 2008).

Notice that, we assume here that the brand i affects positively the perceived quality of services provided by bank i. That is to say that the image of this bank increases the consumers’confidence when purchasing its services. We could also consider the alternative scenario where the image of bank i magnifies the customers’ uncertainty and thus write: \(u_{i}=\bar{u} _{i}-b_{i}.\)

Of course, one could consider a more general framework with a larger number of firms surviving at equilibrium. Notice however, that finding the solution of this new game would become by far havier from a technical view point. Furthermore, as the rationale underlying our findings would be still valid, our argument could be extended to this new setting and the equilibrium restored under a new range of parameter.

Of course, we could have as well considered the alternative timing in which the foreign bank starts to offer to buy the low quality, and then the high quality one, in the case when bank L turns down the offer. However, restricting our analysis to this specific sequential game does not alter the main conclusions of our work.

It is worth noting that this assumption is in line with the literature on the entry dilemma (Eicher and Kang 2005; Müller 2007, inter alia). Further, it seems to be particularly reasonable within the context of retail banking where foreign banks quite often acquire their competitor when entering a new market in order to inherit its brand and the circle of customers loyal to it.

For example, the Benelux and Nordic regions are the most open markets, while in Italy for a long time the resistance to foreign takeover has shaped the retailbanking sector.

References

Boot AW (2000) Relationship firming: what do we know? J Financ Intermed 9:7–25

Degryse H, Ongena S (2008) Competition and regulation in the firming sector: a review of the empirical evidence on the sources of firm rents. In: Thakor A, Boot A (eds) Handbook of financial intermediation and firming. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Eicher T, Kang J (2005) Trade, new direct investment or acquisition: optimal entry modes for multinationals. J Dev Econ 77(1):207–228

European Commission (2007) Report on the retail firming sector inquiry. SEC 106

Görg H (2000) Analyzing new market entry—the choice between greenfield investment and acquisitions. J Econ Stud 27(3):165–181

Grossman G, Shapiro C (1988) Foreign counterfeiting of status goods. Q J Econ 103:79–100

Grunfeld L, Sanna-Randaccio F (2005) Greenfield investment or acquisition? Optimal new entry mode with knowledge spillovers in a Cournot game. Mimeo

Harzing AW (2002) Acquisitions versus greenfield investments: international strategy and management of entry modes. Strateg Manage J 23:211–227

Helpman E, Melitz MJ, Yeaple SR (2004) Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. Am Econ Rev 94:300–316

Hennart JF (2000) Transaction costs theory and the multinational enterprise. In: Pitelis C, Sugden R (eds) The nature of the transnational firm, 2nd edn. Routledge, London

Hennart JF, Park YR (1993) Greenfield vs. acquisition: the strategy of Japanese investors in the United States. Manage Sci 39(9):1054–1070

James C (1987) Some evidence on the uniqueness of firm loans. J Financ Econ 19:217–235

Kim M, Kliger D, Vale B (2003) Estimating switching costs: the case of firming. J Financ Intermed 12:25–56

Müller T (2007) Analyzing modes of new entry: greenfield investment versus acquisition. Rev Int Econ 15(1):93–111

Nocke V, Yeaple S (2007) Cross-border mergers and acquisitions vs. greenfield new direct investment: the role of firm heterogeneity. J Int Econ 72:336–365

Norbäck PJ, Persson L (2008) Cross-border mergers & acquisitions policy in service markets. J Ind Compet Trade 8(3–4):269–293

Pepall LM, Richards DJ (2002) The simple economics of brand stretching. J Bus 75:3

Peria MSM, Mody A (2004) How foreign participation and market concentration impact bank spreads: evidence from Latin America . J Money, Credit Bank 36(3):511–537

Petersen M, Rajan R (1994) The benefits of lending relationships: evidence from small business data. J Finance 49:3–37

Raff H, Ryan M, Stähler F (2006) Asset ownership and new market entry. CESifo Working Paper 1676

Raff H, Ryan M, Stähler F (2009) The choice of market entry mode: greenfield investment, M&A and joint venture. Int Rev Econ Finance 18:3–10

Smith M, Brynjolfsson E (2001) Consumer decision-making at an Internet shopbot: brand still matters. J Ind Econ 49(4):541–558

Tadelis S (1999) What’s in a name? Reputation as a tradeable asset. Am Econ Rev 89(3):548–563

Vale B (1993) The dual role of demand deposits under asymmetric information. Scand J Econ 95:77–95

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank G. De Arcangelis, C. De Vincenti, L. Guiso, G. Rodano for their comments, and two referees whose suggestions prompted a significant improvement in the exposition of these results. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Proposition 1

At the third stage of the game, the new bank can successfully enter the market at equilibrium only when the brand quality b F is sufficiently high and thus lies in between the top and the bottom of the quality ladder. However, the incumbent bank providing the brand whose quality lies at the bottom of the quality ladder is no longer active in the market.

Proof of Proposition 1

Let us focus on the scenario where the quality of the variant offered by the entrant lies at the bottom of the quality ladder. Of course, this analysis can be immediately extended to the alternative scenario where the variant offered by the low quality incumbent lies at the bottom of the quality ladder, while the one marketed by the entrant being in between the top and the bottom of the quality ladder. To this end, it suffices to exchange b L with b F and just repeat the analysis.

In this scenario, the consumer θ H indifferent between being served by bank H or L at prices p H and p L , respectively, writes as

while the consumer θ L indifferent between buying services provided by bank L or F at prices p L and p F

Accordingly, the corresponding demand functions D H (p H , p L ) and D L (p H , p L ) for the national banks H and L, respectively, are

and

for the new bank F. Thus, the respective profits functions write as

From the first order conditions, it is easy to identify the following best reply functions

Thus, solving the above system, we derive the candidate equilibrium prices \( \tilde{p}_{H},\) \(\tilde{p}_{L}\) and \(\tilde{p}_{F}\):

Notice however that (1) implies

which, in turn, implies that

or, equivalently, \(\tilde{p}_{F}\leq 0.\) Accordingly, when (1) is satisfied, then the equilibrium value of p F = 0. In that case, the value of best replies of banks H and L have to be computed against p F = 0, namely,

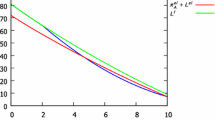

Solving this system in p H and p L , we get the equilibrium prices \( p_{H}^{\ast },\) \(p_{L}^{\ast }\) and \(p_{F}^{\ast }\), namely,

Finally, profits at equilibrium write as follows

□

Proposition 2

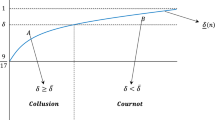

Acquisition of bank L is the second-stage best strategy for the new bank only when the ratio A/B obtained from the consumers’ types range [α, β] is small and the entrant’s brand quality is not different enough from the incumbents’ one so as to ensure mild competition and substantial entrant’s profits.

Proof of Proposition 2

Let us denote by Δ the value b H − b L , Ψ the value b H − b F and define x by \(x=\frac{\alpha }{\beta }.\) The sign of the difference between profits from de novo entry and profits from acquiring bank L, namely

has the same sign as the expression

given that we have assumed \(x\in \left[ \frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{2}\right] ,\) in order to ensure that two, and only two, banks can make positive profits in this market. Denote by Ψ − and Ψ + the roots of the second-order polynomial

Notice now that

-

(i)

the sign of P(Ψ) is the sign of (5) ,

-

(ii)

P(Ψ) is strictly negative for all Ψ whenever \( 64x^{2}-64x+13>0\Leftrightarrow x\in \left[ \frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{2}-\frac{ \sqrt{3}}{8}\right],\)

-

(iii)

P(Ψ) has two roots Ψ − = \(3\Delta \left(\frac{1+8x-8x^{2}- \sqrt{3}\sqrt{-(64x^{2}-64x+13)}}{20-8x+8x^{2}}\right)\) and \(\Psi ^{+}=3\Delta \left(\frac{1+8x-8x^{2}+\sqrt{3}\sqrt{-(64x^{2}-64x+13)}}{20-8x+8x^{2}}\right).\)

Thus, whenever \(x\in \left[ \frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{8}\right]\) the new bank F prefers to buy bank L whatever the value of Ψ; when \(x\in \left(\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{8},\frac{1}{2}\right],\) the new bank F chooses to buy bank L whenever \(\Psi \in \lbrack 0,\Psi ^{-})\) or Ψ ∈ (Ψ + , Δ] and to enter whenever Ψ ∈ (Ψ − , Ψ + ). It is indifferent between the two options when Ψ = Ψ or Ψ = Ψ + .□

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tarola, O., Gabszewicz, J.J. & Laussel, D. To Acquire, or To Compete? An Entry Dilemma. J Ind Compet Trade 11, 369–383 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-010-0082-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-010-0082-1