Abstract

Over the last few years, the emergence of universities’ third mission has significantly affected objectives, sources of funding and financing methods, as well as the management, of universities. Although the university–industry relationships have been widely investigated, several interesting theoretical and empirical issues still remain open in the literature. In this paper we construct an original data set, combining financial information with structural and organizational data on Italian University departments, with a twofold aim. First, to describe the importance and the extent of third-party funding in the Italian system of research as well as the pattern of evolution over the last few years. Second, to investigate the factors that influence both the probability and the intensity of the commitment of departments in third-party activities by building a multi-level framework combining factors at individual, departmental, university and territorial levels. The results obtained suggest a number of policy implications for universities and policy makers. On one hand, universities should explicitly recognize the role of dedicated internal organizations and provide training for professional staff capable of acting as value-added intermediaries. On the other hand, if policy makers wish to improve the relationships between universities and external actors, disciplinary differences across departments as well as regional inequalities in growth levels should be carefully considered, giving up a one-size-fits-all approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 1989, Law 168 endorsed the self-regulation principle and increased universities’ administrative autonomy. Law 537 further elaborated on this new institutional framework, in 1993, by introducing greater freedom for universities in the use of funds coming from the Ministry, and in the possibility of attracting external funding. Following the ministerial decree on the 9th of February 1996, which gave full application to Law 168, universities started to elaborate on their own statutes and internal regulations, which gradually expanded to include different possibilities for leveraging their internal resources and competencies.

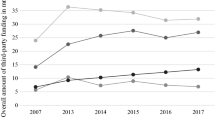

In addition to the descriptive analysis illustrated above, we performed ANOVA tests in order to evaluate if the average rate of participation in third-party activities significantly differ according to factors such as localization, status and size of the universities. Concerning the localization, we found significant differences among the average rate of third-party funds at 5% level of significance over the 6 year period analyzed. However, when we considered as factor the status and size of the universities, the obtained F statistic did not enabled us to reject the null hypothesis of significant differences among the average values for all the years considered. In particular there are not significant differences in the average values among universities of different size (small, medium and large) in the year 2006 and 2009 while for the other years we can reject the null hypothesis at 10% level of significance. Concerning the status of the universities we rejected the null hypothesis of significance differences for the year 2008 at 1% level of significance. Due to the difficulties in comparing data of the various years at department level, we still referred to data at university level. For this reason the interpretation must be carried out with caution since intra-university compensation effects may be in place.

More in detail information regarding age and disciplinary affiliation of professors and researchers are from the MIUR Teaching Databases managed by CINECA while information concerning PhD courses are from PhD course census archive.

The National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Activities is now introducing the new Research Assessment Exercise (“Evaluation of the Quality of Research”—VQR—for the period 2004–2010). Results will be available in 2013.

AQUAMETH (Advanced Quantitative Methods for the Evaluation of the Performance of Public Sector Research) was a research project coordinated by A. Bonaccorsi and C. Daraio within the PRIME Network of Excellence. See Daraio et al. (2011) for a European comparative analysis, and Bonaccorsi and Daraio (2007) for preliminary data. The dataset includes 80 universities, from which the distance education ones were excluded for the analysis in this paper.

It is worth noting that being our analyses conducted at department level, the individual variables we considered were summarized with the aim to be included in the data set (i.e. for the age of professors we considered the average age of the professors in each Department).

Firstly we considered the size of the university (in terms of number of students enrolled) by distinguishing in large universities (with a total number of students enrolled greater than 40,000) medium-sized universities (with a total number of students enrolled ranging between 15,000 and 40,000) and small universities (with a total number of students lower than 15,000). Secondly, we considered the geographical localization of the university. Finally we considered a dummy variable accounting for the existence of an Industrial-Liaison Office within the university.

Before considering these factors into the models we firstly evaluated the existing level of correlation among them in order to avoid the presence of redundant information in the models to be estimated.

The Heckman analysis provides us with a null hypothesis stating that “the selection process and the outcome process are independent of each other.” If we accept the null hypothesis we can conclude that it is possible to estimate two separate models.

They rejected the need for the two equations to be estimated simultaneously. Moreover, a comparison between the values of the coefficients estimated with the truncated regression and with the Heckman procedure highlighted the absence of substantial differences between the two estimates.

The distribution of error terms (ui and εi) is assumed to be bivariate normal with correlation equal to ρ. The two equations are related if ρ ≠ 0; in this case estimating only the outcome equation would induce sample selection bias in the estimation of vector β.

For the probit models, estimation results are presented also referring to marginal effects (M.E.) which are more straightforward to interpret as they show, in general, how a one unit change in one of the regressors affects the predicted probabilities leaving the other variables constant (at their mean).

References

Abramo, G., Cicero, T., & D’Angelo, C. A. (2012). The dispersion of research performance within and between universities as a potential indicator of the competitive intensity in higher education systems. Journal of Informetrics, 6, 155–168.

Abreu, M., Grinevich, V., Hughes, A., & Kitson, M. (2009). Knowledge exchange between academics and the business, public and third sectors. Cambridge: UK Innovation Research Centre.

Agrawal, A., Cockburn, I., & McHale, J. (2006). Gone but not forgotten: Knowledge flows, labor mobility and enduring social relationships. Journal of Economic Geography, 6, 571–591.

Allison, P., & Long, S. (1990). Departmental effects on scientific productivity. American Sociological Review, 55, 469–478.

Anselin, L., Varga, A., & Acs, Z. (1997). Local Geographic Spillovers between University research and high technology innovations. Journal of Urban Economics, 42(3), 422–448.

Arvanitis, S., Kubli, U., & Woerter, M. (2008). University–industry knowledge and technology transfer in Switzerland: What university scientists think about co-operation with private enterprises. Research Policy, 37(10), 1865–1883.

Auranen, O., & Nieminen, M. (2010). University research funding and publication performance—An international comparison. Research Policy, 39, 822–834.

Azagra-Caro, J. M., Archontakis, F., Gutiérrez-Gracia, A., & Fernández-de-Lucio, I. (2006). Faculty support for the objectives of university–industry relations versus degree of R&D cooperation: The importance of regional absorptive capacity. Research Policy, 35(1), 37–55.

Baldini, N., Grimaldi, R., & Sobrero, M. (2007). To patent or not to patent? A survey of Italian inventors on motivations, incentives, and obstacles to university patenting. Scientometrics, 70(2), 333–354.

Bekkers, R., & Bodas Freitas, I. M. (2008). Analyzing knowledge transfer channels between universities and industry: To what degree do sectors also matter? Research Policy, 37(10), 1837–1853.

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2008). Academic entrepreneurs: Organizational change at the individual level. Organization Science, 19(1), 69–89.

Boardman, P. C. (2008). Beyond the stars: The impact of affiliation with university biotechnology centers on the industrial involvement of university scientists. Technovation, 28(5), 291–297.

Boardman, P. C., & Corley, E. A. (2008). University research centers and the composition of research collaborations. Research Policy, 37(5), 900–913.

Boardman, P. C., & Ponomariov, B. L. (2009). University researchers working with private companies. Technovation, 29(2), 142–153.

Bonaccorsi, A., Colombo, M., Guerini, M., & Rossi Lamastra, C. (2012). The spatial range of university knowledge and the creation of knowledge intensive firms. Small Business Economics (Submitted to).

Bonaccorsi, A., & Daraio, C. (2003). Age effects in the organisation of science. The case on the Italian National Research Council. Scientometrics, 58(1), 49–90.

Bonaccorsi, A., & Daraio, C. (2005). Exploring size and agglomeration effects on public research productivity. Scientometrics, 63, 87–120.

Bonaccorsi, A., & Daraio, C. (2007). Universities and strategic knowledge creation. Specialization and performance in Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74.

Bottazzi, L., & Peri, G. (2003). Innovation and spillovers in regions: Evidence from European patent data. European Economic Review, 47(4), 687–710.

Bozeman, B., & Gaughan, M. (2007). Impacts of grants and contracts on academic researchers’ interactions with industry. Research Policy, 36(5), 694–707.

Brandt, T., & Schubert, T. (2012). Is the university model an organizational necessity? Scale and agglomeration effects in science. Scientometrics. doi:10.1007/s11192-012-0834-2.

Breschi, S., & Lissoni, F. (2009). Mobility of skilled workers and co-invention networks: An anatomy of localized knowledge flows. Journal of Economic Geography, 4, 439–468.

Bruno, G., & Orsenigo, L. (2003). Determinanti dei finanziamenti industriali alla ricerca universitaria in Italia. In A. Bonaccorsi (Ed.), Il sistema della ricerca pubblica in Italia. Milan: Franco Angeli.

Carayol, N., & Matt, M. (2004). Does research organization influence academic production? Laboratory level evidence from a large European university. Research Policy, 33, 1081–1102.

Clark, B. R. (1998). Creating entrepreneurial universities: Organizational pathways of transformation. New York: Pergamon.

Clarysse, B., Wright, M., Lockett, A., Van de Velde, E., & Vohora, A. (2005). Spinning out new ventures: A typology of incubation strategies from European research institutions. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 183–216.

Cohen, W. M., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. P. (2002). Links and impacts: The influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science, 48(1), 1–23.

Crescenzi, R., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2007). The territorial dynamics of innovation: a Europe–United States comparative analysis. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(6), 673–709.

Daraio, C., Bonaccorsi, A., et al. (2011). The European University landscape: A micro characterization based on evidence from the Aquameth project. Research Policy, 40, 148–164.

D’Este, P., & Patel, P. (2007). University–industry linkages in the UK: What are the factors determining the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy, 36(9), 1295–1313.

D’Este, P., & Perkmann, M. (2011). Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(3), 316–339.

Etzkowitz, H. (1998). The norms of entrepreneurial science: Cognitive effects of the new university–industry linkages. Research Policy, 27, 823–833.

Etzkowitz, H., Webster, A., Gebhardt, C., & Terra, B. R. C. (2000). The future of the university and the university of the future: Evolution of ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Research Policy, 29, 313–330.

European Commission (2007). Improving knowledge transfer between research institutions and industry across Europe: Embracing open innovation, COM (2007) 182 final, Bruxelles.

Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Santoni, S., & Sobrero, M. (2012). Complements or substitutes? The role of universities and local context in supporting the creation of academic spin-offs. Research Policy, 40(2011), 1113–1127.

Florida, R., & Cohen, W. M. (1999). Engine or infrastructure? The university role in economic development. In L. M. Branscomb, F. Kodama, & R. Florida (Eds.), Industrializing knowledge: University–industry linkages in Japan and the United States (pp. 589–610). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fontana, R., Geuna, A., & Matt, M. (2003). Firm size and openness: The driving forces of university–industry collaboration. SPRU Electronic Working Papers Series, paper no. 103. Available at http://139.184.32.141/Units/spru/publications/imprint/sewps/sewp103/sewp103.pdf.

Fukugawa, N. (2012) University spillovers into small technology-based firms: channel, mechanism, and geography. Journal of Technology Transfer, doi:10.1007/s10961-012-9247-x, online first.

Geiger, R. L. (2004). Knowledge and money. Research universities and the paradox of the marketplace. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Geuna, A. (2001). The changing rationale for European university research funding: Are there negative unintended consequences? Journal of Economic Issues, 35, 607–632.

Giuliani, E., & Arza, V. (2008). What drives the formation of valuable ‘University–industry’ linkages? An under-explored question in a hot policy debate. SPRU Electronic Working Papers, Paper No. 170.

Greene, W. H. (1993). Econometric analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Gulbrandsen, M., & Slipersæter, S. (2007). The third mission and the entrepreneurial university model. In A. Bonaccorsi & C. Daraio (Eds.), Universities and strategic knowledge creation: Specialization and performance in Europe (pp. 112–143). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Gulbrandsen, M., & Smeby, J. C. (2005). Industry funding and university professors’ research performance. Research Policy, 34(6), 932–950.

Hall, B. H., Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2000). Universities as research partners. NBER Working Papers N°7643.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47, 153–161.

Herbst, M. (2009). Financing public universities. The case of performance funding. Dordrecht: Springer.

Hottenrott, H. (2011). The role of research orientation for attracting competitive research funding, K.U. Leuven. Dept. of Managerial Economics, Strategy and innovation, OR 1104, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

Hottenrott, H., & Thorwarth S. (2010). Industry funding of university research and scientific productivity, ZEW Discussion Paper No. 10–105, Mannheim.

Hulsbeck, M., Lehmann, E. E., & Starnecker, A. (2011). Performance of technology transfer offices in Germany. Journal of Technology Transfer, doi:10.1007/s10961-011-9243-6, online first.

Jain, S., George, G., & Maltarich, M. (2009). Academics or entrepreneurs? Investigating role identity modification of university scientists involved in commercialization activity. Research Policy, 38(6), 922–935.

Krabel, S., & Mueller, P. (2009). What drives scientists to start their own company? An empirical investigation of Max Planck Society scientists. Research Policy, 38, 947–956.

Landry, R., Amara, N., & Rherrad, I. (2006). Why are some university researchers more likely to create spin-offs than others? Evidence from Canadian universities. Research Policy, 35(10), 1599–1615.

Laursen, K., Reichstein, T., & Salter, A. (2011). Exploring the effect of geographical proximity and university quality on university–industry collaboration in the United Kingdom. Regional Studies, 45(4), 507–523.

Lee, Y. S. (1996). ‘Technology transfer’ and the research university: A search for the boundaries of university–industry collaboration. Research Policy, 25(6), 843–863.

Lee, Y. S. (2000). The sustainability of university–industry research collaboration: An empirical assessment. Journal of Technology Transfer, 25(2), 111–133.

Lepori, B., van den Besselaar, P., Dinges, M., Potì, B., Reale, E., Slipersaeter, S., et al. (2007). Convergence versus national specificities in research policies. An empirical study on public project funding. Research Evaluation, 27(2), 83–93.

Lin, M.-W., & Bozeman, B. (2006). Researchers’ industry experience and productivity in university–industry research centers: A “scientific and technical human capital” explanation. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(2), 269–290.

Link, A. N., Siegel, D. S., & Bozeman, B. (2007). An empirical analysis of the propensity of academics to engage in informal university technology transfer. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 641–655.

Louis, K. S., Blumenthal, D., Gluck, M., & Stoto, M. A. (1989). Entrepreneurs in academe: An exploration of behaviors among life scientists. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34(1), 110–131.

Mansfield, E. (1995). Academic research underlying industrial innovations: Sources, characteristics, and financing. Review of Economics and Statistics, 77(1), 55–65.

McKelvey, M., & Holmén, M. (2009). Learning to compete in European universities: From social institution to knowledge business. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishers.

Meyer-Krahmer, F., & Schmoch, U. (1998). Science-based technologies: University–industry interactions in four fields. Research Policy, 27(8), 835–851.

Moutinho, P., Fontes, M., & Godinho, M. (2007). Do individual factors matter? A survey of scientists’ patenting in Portuguese public research organisations. Scientometrics, 70(2), 355–377.

Owen-Smith, J., & Powell, W. W. (2001). To patent or not: Faculty decisions and institutional success at technology transfer. Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(1), 99–114.

Perkmann, M., & Walsh, K. (2008). Engaging the scholar: Three forms of academic consulting and their impact on universities and industry. Research Policy, 37(10), 1884–1891.

Perkmann, M., & Walsh, K. (2009). The two faces of collaboration: Impacts of university industry relations on public research. Industrial and Corporate Change, 18(6), 1033–1065.

Phan, P. H., & Siegel, D. S. (2006). The effectiveness of university technology transfer: Lessons learned from qualitative and quantitative research in the US and UK. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 66–144.

Ponds, R., van Oort, F., & Frenken, K. (2007). The geographical and institutional proximity of research collaboration networks. Papers in Regional Science, 86, 423–443.

Ponomariov, B. L. (2008). Effects of university characteristics on scientists’ interactions with the private sector: An exploratory assessment. Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(5), 485–503.

Ponomariov, B., & Boardman, C. P. (2008). The effect of informal industry contacts on the time university scientists allocate to collaborative research with industry. Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(3), 301–313.

Renault, C. (2006). Academic capitalism and university incentives for faculty entrepreneurship. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(2), 227–239.

Rothaermel, F. T., Agung, S., & Jiang, L. (2007). University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 691–791.

Schartinger, D., Rammer, C., Fischer, M. M., & Fröhlich, J. (2002). Knowledge interactions between universities and industry in Austria: Sectoral patterns and determinants. Research Policy, 31(3), 303–328.

Schartinger, D., Schibany, A., & Gassler, H. (2001). Interactive relations between universities and firms: Empirical evidence for Austria. Journal of Technology Transfer, 26, 255–269.

Schmoch, U., & Schubert, T. (2009). Sustainability of incentives for excellent research. Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research Discussion Paper, Karlsruhe.

Sellenthin, M. O. (2009). Technology transfer offices and university patenting in Sweden and Germany. Journal of Technology Transfer, 34(6), 603–620.

Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D., & Link, A. (2003). Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the relative productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study. Research Policy, 32(1), 27–48.

Slaughter, S., & Leslie, L. L. (1997). Academic capitalism: Politics, policies, and the Entrepreneurial University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Stephan, P. (1996). The economics of science. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(3), 1199–1235.

Van Dierdonck, R., Debackere, K., & Engelen, B. (1990). University–industry relationships: How does the Belgian academic community feel about it? Research Policy, 19(6), 551–566.

Varga, A. (2000). Local academic knowledge transfers and the concentration of economic activity. Journal of Regional Science, 40(2), 289–309.

Weick, K. E. (1982). Management of organizational change among loosely coupled elements. In P. S. Goodman (Ed.), Change in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Welsh, R., Glenna, L., Lacy, W., & Biscotti, D. (2008). Close enough but not too far: Assessing the effects of university–industry research relationships and the rise of academic capitalism. Research Policy, 37(10), 1854–1864.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed.). USA: The Mit Press.

Wright, M., Clarysse, B., Lockett, A., & Knockaert, M. (2008). Mid-range universities’ linkages with industry: Knowledge types and the role of intermediaries. Research Policy, 37, 1205–1223.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two anonymous referees for their useful suggestions concerning our study. Comments on a previous version of the study, presented at the 5th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (Madrid, November 2011) were also helpful.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Andrea Bonaccorsi: On leave from Department of Energy and Systems Engineering, University of Pisa.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonaccorsi, A., Secondi, L., Setteducati, E. et al. Participation and commitment in third-party research funding: evidence from Italian Universities. J Technol Transf 39, 169–198 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9268-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9268-5

Keywords

- University–industry relations

- Third-party research

- Italian University department

- Heckman selection model