Abstract

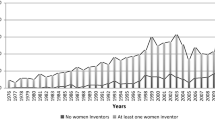

A growing stream of the academic literature has investigated the factors that hamper the participation of women researchers in patenting and commercialization activities; however, limited research has examined the policies that address these forms of the gender gap. In this paper, we explore whether the ownership arrangements of university patents and the presence of university-level support measures such as technology transfer offices and linkages with science and technology parks are positively associated with women’s involvement in academic patenting. We test our hypotheses on a sample of 2538 academic patents by Italian inventors in the period 1996–2007. The results of our analyses highlight a positive role of university policies in addressing the gender gap in technology transfer activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the APE-INV dataset, Italian academic patents were identified through a process of name matching between disambiguated inventors of Italian EPO patents and academic personnel, and the latter's names were made available in 2000, 2005 and 2009 by the Italian Ministry of Education. This procedure produced “professor-patent” pairs that were obtained by attributing to each professor the patents that had been signed by the matched inventors. For a more detailed description of the dataset, the disambiguation process and matching algorithm, see Lissoni et al. (2013).

The TASTE dataset systematically collects information on the population of 95 Italian universities, including the characteristics, in terms of economic development and innovation levels, of the 20 Italian regions in which they are located (Bolzani et al, 2014).

Since 2014, ANVUR began a systematic data collection effort on third mission activities that were undertaken by Italian universities, based on a mandate of the Italian Ministry for University and Research. Such information is publicly available on the ANVUR website (under the “SUA-RD Terza Missione” section). This section includes information about the participation of the university in a science and technology park, and the year of activation of such participation.

If, for a given patent, there are academic inventors from more than one university, we consider the university with the oldest date of TTO creation to build this variable.

We consider the 8 main sections of IPC patent classification scheme to construct such dummy variables: Human necessities; Performing operations, Transporting; Chemistry, Metallurgy; Textiles, Paper; Fixed constructions; Mechanical engineering; Physics; Electricity. In our estimations, Human necessities is the baseline dummy.

Furthermore, if we focus on the distribution of university-owned patents among universities with and without TTO, we find that, on average, the proportion of university-owned patents coming from universities without TTOs is significantly lower in respect to universities with TTOs (32.3 vs. 67.7%). This scenario is particularly pronounced from 2005, with over 93% of university-owned patents coming from universities with a TTO. This result supports the idea that TTOs act as facilitator for the development of patents owned by the mother universities. We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting us to point out this distinction.

We use the term “university-affiliated” and “academic” interchangeably to say that an inventor comes from academia.

References

Baldini, N., Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., & Sobrero, M. (2010). The institutionalisation of university patenting activity in Italy: Diffusion and evolution of organisational practices. Cambridge Journal Economics (special issue) workshop “universities and the knowledge economy”, June 28–29, 2010.

Baldini, R., Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., & Sobrero, M. (2014). Organisational change and the institutionalisation of university patenting activity in Italy. Minerva,52(1), 27–53.

Baldini, N., Grimaldi, R., & Sobrero, M. (2006). Institutional changes and the commercialization of academic knowledge: A study of Italian universities’ patenting activities between 1965 and 2002. Research Policy,35(4), 518–532.

Baldini, N., Grimaldi, R., & Sobrero, M. (2007). To patent or not to patent? A survey of Italian inventors on motivations, incentives, and obstacles to university patenting. Scientometrics,70(2), 333.

Bolzani, D., Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Santoni, S., & Sobrero, M. (2014). Fifteen years of academic entrepreneurship in Italy: Evidence from the taste project. Technical report: University of Bologna, June 2014. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2460301. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Bozeman, B. (2000). Technology transfer and public policy: A review of research and theory. Research Policy,29(4–5), 627–655.

Bradley, S. R., Hayter, C. S., & Link, A. N. (2013). Proof of concept centers in the United States: An exploratory look. Journal of Technology Transfer,38(4), 349–381.

Chugh, H. (2004). New academic venture development: Exploring the influence of the technology transfer office on university spinouts. Working paper, Tanaka Business School, Imperial College London.

Corley, E., & Gaughan, M. (2005). Scientists’ participation in university research centers: What are the gender differences? The Journal of Technology Transfer,30(4), 371–381.

Crespi, G. A., Geuna, A., Nomaler, O., & Verspagen, B. (2010). University IPRs and knowledge transfer: Is university ownership more efficient? Economics of Innovation and New Technology,19(7), 627–648.

De Melo-Martín, I. (2013). Patenting and the gender gap: Should women be encouraged to patent more? Science and Engineering Ethics,19(2), 491–504.

Debackere, K., & Veugelers, R. (2005). The role of academic technology transfer organizations in improving industry science links. Research Policy,34(3), 321–342.

Ding, W. W., Murray, F., & Stuart, T. E. (2006). Gender differences in patenting in the academic life sciences. Science,313, 665–667.

Ding, W. W., Murray, F., & Stuart, T. E. (2013). From bench to board: Gender differences in university scientists’ participation in corporate scientific advisory boards. Academy of Management Journal,56(5), 1443–1464.

Dornbusch, F., Schmoch, U., Schulze, N., & Bethke, N. (2013). Identification of university-based patents: A new large-scale approach. Research Evaluation,22, 52–63.

Etzkowitz, H., Kemelgor, C., & Uzzi, B. (2000). Athena unbound: The advancement of women in science and technology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, M., Feller, I., Bercovitz, J., & Burton, R. (2002). Equity and the technology transfer strategies of American research universities. Management Science,48(1), 105–121.

Ferber, M., & Loeb, L. (1997). Academic couples: Problems and promise. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Fox, M. F., & Ferri, V. C. (1992). Women, men, and their attributions for success in academe. Social Psychology Quarterly,55, 257–271.

Frietsch, R., Haller, I., Funken-Vrohlings, M., & Gruppa, H. (2009). Gender-specific patterns in patenting and publishing. Research Policy,38, 590–599.

Geuna, A., & Nesta, L. (2006). University patenting and its effects on academic research: The emerging European evidence. Research Policy,35, 790–807.

Geuna, A., & Rossi, F. (2011). Changes to university IPR regulations in Europe and the impact on academic patenting. Research Policy,40, 1068–1076.

Giuri, P., Mariani, M., Brusoni, S., Crespi, G., Francoz, D., Gambardella, A., et al. (2007). Inventors and invention processes in Europe: Results from the PatVal-EU survey. Research Policy,36(8), 1107–1127.

Giuri, P., Munari, F., & Pasquini, M. (2013). What determines university patent commercialization? Empirical evidence on the role of university IPR ownership. Industry and Innovation,20(5), 488–502.

Grimaldi, R., Kenney, M., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2011). 30 years after Bayh–Dole: Reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy,40, 1045–1057.

Hunt, J., Garant, J. P., Herman, H., & Munroe, D. J. (2012). Why don’t women patent? NBER working paper.

Hunt, J., Garant, J. P., Herman, H., & Munroe, D. J. (2013). Why are women underrepresented amongst patentees? Research Policy,42, 831–843.

Jacobs, J. A., Gerson, K., & Jacobs, J. A. (2004). The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lissoni, F. (2012). Academic patenting in Europe: An overview of recent research and new perspectives. World Patent Information,34, 197–205.

Lissoni, F., Llerena, P., McKelvey, M., & Sanditov, B. (2007). Academic patenting in Europe: New evidence from the KEINS database. Research Evaluation,17(2), 87–102.

Lissoni, F., Pezzoni, M., Poti, B., & Romagnosi, S. (2013). University autonomy, the professor privilege and academic patenting: Italy, 1996–2007. Industry and Innovation,20(5), 399–421.

Lofsten, H., & Lindelof, P. (2002). Science parks and the growth of new technology based firms, academic-industry links, innovation and markets. Research Policy,31(6), 859–876.

Long, J. S. (2001). From scarcity to visibility: Gender differences in the careers of doctoral scientists and engineers. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Long, J. S., & McGinnis, R. (1985). The effects of the mentor on the academic career. Scientometrics,7(3–6), 255–280.

Louis, K. S., Jones, L. M., Anderson, M. S., Blumenthal, D., & Campbell, E. G. (2001). Entrepreneurship, secrecy, and productivity: A comparison of clinical and non-clinical faculty. Journal of Technology Transfer,26, 233–245.

Mann, R. J., & Sager, T. W. (2007). Patents, venture capital, and software start-ups. Research Policy,36(2), 193–208.

Markman, G. D., Gianiodis, P. T., Phan, P. H., & Balkin, D. B. (2005). Innovation speed: Transferring university technology to market. Research Policy,34, 1058–1075.

Markman, G. D., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2008). Research and technology commercialization. Journal of Management Studies,45, 1401–1423.

Mason, M. A., & Goulden, M. (2004). Marriage and baby blues: Redefining gender equity and the academy. Annals of American Political and Social Scientist,596, 86–103.

Mauleon, E., & Bordons, M. (2009). Male and female involvement in patenting activity in Spain. Scientometrics,83, 605–621.

McCullagh, P. (1983). Quasi-likelihood functions. The Annals of Statistics,11, 59–67.

Meng, Y. (2016). Collaboration patterns and patenting: Exploring gender distinctions. Research Policy,45, 56–67.

Meyer, J. P. (2013). The science–practice gap and employee engagement: It’s a matter of principle. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne,54(4), 235–245.

Morgan, R. P., Kruytbosch, C., & Kannankutty, N. (2001). Patenting and innovation activity of U.S. scientists and engineers in the academic sector: Comparisons with industry. Journal of Technology Transfer,26, 173–183.

Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2007). From human capital to social capital: A longitudinal study of technology-based academic entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,31(6), 909–935.

Mowery, D. C., & Ziedonis, A. A. (2002). Academic patent quality and quantity before and after the Bayh–Dole act in the United States. Research Policy,31(3), 399–418.

Munari, F., Pasquini, M., & Toschi, L. (2015). From the lab to the stock market? The characteristics and impact of university-oriented seed funds in Europe. The Journal of Technology Transfer,40(6), 948–975.

Munari, F., Rasmussen, E., Toschi, L., & Villani, E. (2016). Determinants of the university technology transfer policy-mix: A cross-national analysis of gap-funding instruments. Journal of Technology Transfer,41(6), 1377–1405.

Munari, F., Sobrero, M., & Toschi, L. (2018). The university as a venture capitalist? Gap funding instruments for technology transfer. Technological Forecasting and Social Change,127, 70–84.

Murray, F., & Graham, L. (2007). Buying science and selling science: Gender differences in the market for commercial science. Industrial and Corporate Change,16(4), 657–689.

Mustar, P., & Wright, M. (2010). Convergence or path dependency in policies to foster the creation of university spin-off firms? A comparison of France and the United Kingdom. Journal of Technology Transfer,35, 42–65.

Naldi, F., Luzi, D., Valente, A., & Vannini Parenti, I. (2004). Scientific and technological performance by gender. In H. F. Moed, W. Glanzel, & U. Schmoch (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative science and technology research.

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2005). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? Working paper no. 11474, National Bureau of economic research working paper.

O’Shea, R. P., Allen, T. J., Chevalier, A., & Roche, F. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation, technology transfer and spin off performance of U.S. universities. Research Policy,34, 994–1009.

Phan, P. H., & Siegel, D. S. (2006). The effectiveness of university technology transfer: Lessons learned, managerial and policy implications, and the road forward. Working paper no. 0609, Rensselaer working papers in economics.

Phan, P. H., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2005). Science parks and incubators: Observations, synthesis and future research. Journal of Business Venturing,20(2), 165–182.

Popp Berman, E. (2008). Why did universities start patenting? Institution-building and the road to the Bayh–Dole act. Social Studies of Science,38(6), 835–871.

Powers, J. B., & McDougall, P. P. (2005). University start-up formation and technology licensing with firms that go public: A resource-based view of academic entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing,20(3), 291–311.

Ranga, M., & Etzkowitz, H. (2010). Athena in the world of techne: The gender dimension of technology, innovation and entrepreneurship. Journal of Technology Management and Innovation,5(1), 1–12.

Rasmussen, E., Moen, Ø., & Gulbrandsen, M. (2006). Initiatives to promote commercialization of university knowledge. Technovation,26, 518–533.

Roos, P., & Gatta, M. (2009). Gender (in)equity in the academy: Subtle mechanisms and the production of inequality. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility,27(3), 177–200.

Rosa, P., & Dawson, A. (2006). Gender and the commercialization of university science: Academic founders of spinout companies. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development,18, 341–366.

Rosser, S. V. (2009). The gender gap in patenting: Is technology transfer a feminist issue? Feminist Formations,21(2), 65–84.

Shaw, S., & Cassell, K. (2007). “That’s not how I see it”: Female and male perspectives on the academic role. Women in Management Review,22(6), 497–515.

Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D., & Link, A. (2003a). Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the relative productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study. Research Policy,32, 27–48.

Siegel, D. S., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2003b). Science Parks and the performance of new technology based firms: A review of UK based evidence and an agenda for future research. Small Business Economics,20(2), 177–184.

Sonnert, G., & Holton, G. (1996). Career patterns of women and men in the sciences. American Scientist,84, 63–71.

Stephan, P. E., & El-Ganainy, A. (2007). The entrepreneurial puzzle: Explaining the gender gap. Journal of Technology Transfer,32, 475–487.

Stuart, T. E., & Ding, W. W. (2006). When do scientists become entrepreneurs? The social structural antecedents of commercial activity in the academic life sciences. American Journal of Sociology,112(1), 97–144.

Sugimoto, C. R., Ni, C., West, J. D., & Larivière, V. (2015). The academic advantage: Gender disparities in patenting. PLoS ONE,10(5), e0128000.

Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2015). The engagement gap: Exploring gender differences in University–Industry collaboration activities. Research Policy,44(6), 1176–1191.

Technopolis. (2008). Evaluation on policy: Promotion of women innovators and entrepreneurship. GKH, Technopolis: Final Report.

Thursby, J., Fuller, A. W., & Thursby, M. (2009). US faculty patenting: Inside and outside the university. Research Policy,38(1), 14–25.

Thursby, J. G., Jensen, R., & Thursby, M. C. (2001). Objectives, characteristics and outcomes of university licensing a survey of major U.S. universities. The Journal of Technology Transfer,26, 59–72.

Thursby, J. G., & Thursby, M. C. (2005). Gender patterns of research and licensing activity of science and engineering faculty. The Journal of Technology Transfer,30(4), 343–353.

Wedderburn, R. W. (1974). Quasi-likelihood functions, generalized linear models, and the Gauss–Newton method. Biometrika,61(3), 439–447.

Whittington, K. B. (2007). Employment sectors as opportunity structures: The effects of location on male and female scientific dissemination. Stanford, CA: Department of Sociology, Stanford University.

Whittington, K. B., & Smith-Doerr, L. (2005). Women and commercial science: Women’s patenting in the life sciences. Journal of Technology Transfer,30, 355–370.

Whittington, K. B., & Smith-Doerr, L. (2008). Women inventors in context: Disparities in patenting across academia and industry. Gender & Society,22, 194.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Financial support from the EC project 217299 InnoS&T, from the EIBURS programme of the European Investment Bank (“Financing Knowledge Transfer in Europe”—FiNKT project) and from the PRIN-MIUR project (“Market and non-market mechanisms for the exchange and diffusion of innovation: when do they work, when they do not work, and why should we care”, CUP B41J12000160008) is gratefully acknowledged. Special acknowledgements go to Francesco Lissoni and Michele Pezzoni for kindly providing access to the APE-INV database (Academic Patenting in Europe), and to Riccardo Fini for kindly providing access to the TASTE database (Taking Stock: External Engagement by Academics).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giuri, P., Grimaldi, R., Kochenkova, A. et al. The effects of university-level policies on women’s participation in academic patenting in Italy. J Technol Transf 45, 122–150 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9673-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9673-5