Abstract

Determination of 14C, 55Fe, 63Ni and gamma emitters in two different types of activated reactor pressure vessel (RPV) steel samples were carried out. The gamma emitters were analysed using HPGe detectors with ISOCS and standard geometry calibrations. Two radioanalytical procedures for the 14C, 55Fe, 63Ni analysis were developed using inactive samples and activated samples were analysed using modified procedures. A Monte Carlo code was used for the modelling of the activation results. The obtained measured and calculated results were comparable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During operation of a nuclear reactor, excess neutrons are absorbed into the reactor structures causing activation of structure materials. Therefore, during decommissioning, the activated materials need to be characterised, namely their radiological, physical and chemical properties need to be determined, in order to ensure safe dismantling, processing, storage and final disposal procedures.

The characterisation of the activated materials in decommissioning projects is a challenging task due to broad spectrum of materials, sometimes high dose rates, varying analytical techniques and representativeness of the characterised sample, to name a few. Due to the challenges, implementation of the characterisation needs to be planned case-by-case considering the objective of the characterisation. In some cases, very precise characterisation may be needed and be possible to perform whereas in other cases a good estimate may need to be good enough.

In general, a scaling factor is experimentally determined for each material in order to carry out efficient waste categorisation [1]. The scaling factors link difficult to measure radionuclides (DTM) with easy to measure radionuclides, namely gamma emitters such as 60Co, 152Eu and 137Cs or other types of radionuclides. The scaling factors are material and reactor specific and thus they need to be determined separately for each reactor. After determination of the scaling factors, the total nuclide vectors and activities of waste packages can be carried out by measuring only the gamma emitters and calculating the DTM.

Modelling provides a non-destructive approach to waste characterisation. This is an important technique especially in the early phases of a decommissioning project when the fuel may still be inside the shut-down reactor core and components close to the core cannot be sampled. The neutron activation processes can be calculated by modelling the neutron fluxes in the reactor structures with a neutron transport code such as MCNP [2] and combining this data with the reactor operating history and activation reaction cross sections with a point-depletion code such as ORIGEN-S [3].

Modelling provides reasonable estimates of material specific activities and nuclide vector, but it always requires detailed input data on material chemical compositions. Moreover, calculation models also contain approximations e.g. on activating element distribution in the material and calculated activity results need to be validated with measurements.

Analytical techniques used in the determination of the scaling factors are divided to non-destructive (NDA) and destructive analysis (DA). Gamma spectrometry is a well established NDA technique for analysis of gamma emitting radionuclides and it is routinely used in analysis of different samples varying in physical form (e.g. gas, liquid or solid), size (e.g. sub-grams to hundreds of kilograms) and origin (e.g. industry, environment, medicine etc.). In the case of activated materials, the physical form of the sample is most often solid and thus gamma spectrometric analysis is a straightforward process when appropriate calibration techniques are used. Traditionally, standard geometry calibration is used for the counting efficiency calibration. Standard geometry calibrations are carried out for the gamma detector in regular intervals using known amounts of radionuclides in specific geometries. The use of the standard geometry calibration is convenient in cases when the samples can be analysed in constant geometries. Another versatile calibration technique based on mathematical efficiency calibrations is used in ISOCS (In-Situ Object Counting System) measurement set-up. In this case, the gamma detector has been characterised for different counting efficiencies and geometries using point sources and a MCNP code. With this technique, the counting efficiencies are derived from size of the object, thicknesses and densities of the container and material, possible collimators, and distance from the detector. Therefore, different sizes and shapes of samples can be analysed as long as above mentioned parameters are known.

DA techniques are needed for the analysis of DTM, which is a common acronym used for the characterisation of alpha and beta emitters in decommissioning waste. Due to the detection methods via alpha spectrometry and liquid scintillation counting (LSC), the DTM radionuclides need to be separated from the solid matrix, separated from each other, and purified from other radionuclides using radiochemical methods. Variety of DTM radionuclides (e.g. 3H, 14C, 36Cl, 41Ca, 55Fe, 59Ni, 63Ni etc.) in various activated materials (e.g. steel, concrete, graphite, aluminium, lead etc.) require development of radiochemical methods which can take several days to complete. In some cases, such as characterisation of DTM in reactor graphite, the difficulty in the radiochemical method is in the solubility of the sample whereas in some cases, such as in the case of steel samples, the difficulty is in the purity of the radiochemically separated DTM, for example interference of 60Co in 63Ni fraction.

In general, the characterisation of the activated reactor materials is a multistep procedure, in which the NDA and DA techniques can be used in combination reinforcing each other as the characterisation project progresses. Currently, these techniques are used in practise in the characterisation of FiR1 TRIGA Mark II research reactor in Finland [4].

This paper presents a comparison of calculation and experimental analysis in determination of 14C, 55Fe, 63Ni and gamma emitters in two different types of activated Reactor Pressure Vessel (RPV) steel samples. The activation calculations were made possible by known irradiation history and chemical compositions of the steel samples. Radiochemical method development was carried out using corresponding inactive steel samples prior to analysis of activated steel samples. The experimental analysis were carried out using two combinations (1) gamma emitters via ISOCS calibration and radiochemical analysis of 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni and (2) gamma emitters via standard geometry calibration and radiochemical analysis of 55Fe and 63Ni. The radiochemical analysis were based on similar techniques but the final procedures were different due to the different approaches chosen. The approaches will be discussed in Experimental chapter.

Inactive and activated RPV steel samples

The studied RPV steel samples were of Boiling Water Reactor (BWR) type and VVER-440 Pressurised Water Reactor type. Due to confidentiality reason, exact steel specifications are not presented. However, the activating elements studied in this article are listed in Table 1. Apart from nitrogen, the quantities in the table are based on a Quantovac optical emission spectrometry measurements. The exact amount of nitrogen in the VVER steel was also not reported and therefore, the same concentration was used for VVER steel as reported for BWR steel. The uncertainties for the elemental analysis of Fe, Ni, Co and C were assumed to be 10%. A higher uncertainty of 25% was estimated for nitrogen, taking into account possible heterogeneity in the material microstructure.

Sample preparation

The steel samples were cut from 10 × 10 mm steel bars using an Electric Discharge Machine (EDM). The sliced samples were first dipped into oxide removal solution (HCl:H2O:hexamethylenetetramine) and then washed with water and ethanol in order to stop the oxidation (e.g. rusting). The samples were let to air dry and placed into plastic bags. The masses of the activated samples were between 0.183 and 0.189 g. In total 32 RPV steel samples were cut and labelled. Inactive samples were labelled as BWR_1 to BWR_8 and VVER_1 to VVER_8 and activated samples as BWR_a to BWR_h and VVER_a to VVER_h. Samples 1 to 4 and a to d were studied at Helsinki University whereas samples 5 to 8 and e to h were studied at VTT.

Activation calculations

As material is irradiated with neutrons, activation of stable isotopes to unstable isotopes occur depending on the neutron flux. Assuming that the irradiation occurs at constant flux, the time dependence of specific activity during neutron irradiation is governed by Eq. (1)

where \( \lambda_{n} \) is the decay constant of the activation product n, t is time, k is the number of energy groups and the sum term is the total reaction rate of the activation reaction as calculated from the group-wise constants. Taking into account also the decay of the activation product after irradiation, the contribution of irradiation cycle c to the total activity on reference date can be estimated with Eq. (2)

where \( t_{dec,c} \) is the time between the end of cycle c and the reference date.

The nuclides studied in this article are formed via the reactions listed in Table 2. These reactions occur in nuclear reactors mainly with thermal neutrons. Column 4 lists also the respective activation reaction cross sections in barns at neutron velocity of υ0 (2200 m s−1) [5]. The fast neutron reaction 63Cu(n,p)63Ni was considered minor, due to its small absorption cross section and reported small copper impurity

For comparison with measurement results, VTT calculated the activities using a point kinetic code ORIGEN-S [3]. The neutron spectrum was highly thermal with reported cadmium ratios of 1.64 and 1.27, for VVER and BWR samples respectively. The irradiation history data was supplied by the owners of the VVER and BWR steel samples. Reaction cross sections in ORIGEN-S were END/B-VI formatted. The samples within the steel types were assumed to have the same material composition and irradiation history. VVER steel samples had been irradiated with thermal neutron dose of 5.63 × 1019 n cm−2 and decay time was 30 years. BWR samples had been irradiated with a thermal neutron dose of 1.26 × 1018 n cm−2 and decay time was 10 years. Both calculated and measured activities were decay corrected to fixed reference dates.

Experimental

Two radiochemical method developments for the analysis of 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni (method 1) and for the analysis of 55Fe and 63Ni (method 2) were carried out using inactive steel samples. Since 60Co was foreseen as a major interference for the 55Fe and 63Ni analysis, stable Co was also analysed in the Fe and Ni fractions. After the method developments and analysis of inactive and some activated samples, two crucial constraints were observed. Firstly, large amount of Fe was problematic in separation of Fe and Ni, and secondly, effective purification of Ni from Co was essential. Therefore, the radiochemical methods 1 and 2 were modified using separate approaches (1) pure 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni fractions in the expense of yield, namely method 1.1 and (2) pure 55Fe and 63Ni fractions with high yields, namely method 2.1. The method 1 and 2 are presented in following sub-chapters and the radiochemical method development processes and the modified methods 1.1 and 2.1 are discussed in the results chapter.

The activated steel samples were analysed for gamma emitters prior to radiochemical analysis. Two different gamma spectrometric analyses were utilised, namely High Purity Germanium detector using ISOCS calibration for samples a-h at VTT and GX 8021 HPGe gamma spectrometer (Canberra) with Genie 2000 Gamma Acquisition & Analysis program (Canberra) using standard geometry calibration for samples a-d in Helsinki University. The measurement approaches are further discussed in following sub-chapters. All activity results were decay corrected to reference dates.

Chemicals and equipment used in methods 1 and 1.1

All chemicals and reagents (Na2CO3, NaOH, NH4OH, NH4Ctr i.e. ammonium citrate, NiCl2 6H2O) were of analytical grade. Solutions were prepared into Milli-Q water. Bases and acids were of analytical grade with concentration of 85 wt% H3PO4, 25 wt% NH4OH, 95–97 wt% H2SO4, 65 wt% HNO3, 36–38 wt% HCl, 72 wt% HClO4. Ion exchange columns were prepared using AG 1 × 450–100 mesh anion exchange resin (BioRad) and extraction chromatography columns using Ni-Resin B 100–150 µm (Triskem International).

Orion 2 Star pH Benchtop pH meter combined with Ross combination pH electrode (Thermo Scientific) with pH 4 (AVS TITRINORM, VWR Chemicals), 7 (AVS TITRINORM, VWR Chemicals) and 13 (J.T Baker buffer solution) buffer solutions was used for the pH measurements. 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni were analysed using HIDEX 300 SL liquid scintillation counter with TDCR technology for the counting efficiency determinations. Samples were mixed with HiSafe 3 (Perkin Elmer) liquid scintillation cocktail and let to stabilise at least over night before measurement. 5 ml of 14C sample solutions and 1 ml of 55Fe and 63Ni sample solutions were mixed with 10 ml of liquid scintillation cocktail. Longer stabilisation times were used for 14C samples in which luminescence remained longer. Elemental and radiochemical yield analyses were carried out using Agilent SVDV 5100 ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry). Fe was analysed using radial view and 238.204 nm and 259.940 nm wavelengths. Ni was analysed using radial view and 216.555 nm and 231.604 nm wavelengths. Co was analysed using radial view and 228.615 nm and 238.892 nm wavelengths. Two wavelengths for each element were analysed in order to indicate if any interferences from other elements was present. Since the wavelengths gave consistent results, interferences did not occur. Samples were diluted into 1% suprapur HNO3 solution. Fe, Ni, Co standards were prepared using IV-Stock-21 inorganic ventures 10 ppm 5% (v/v) HNO3 multielement standard.

Chemicals and equipment used in methods 2 and 2.1

Similar to methods 1 and 1.1, all reagents were of analytical grade and Milli-Q water was used for preparing the reagent solutions. Acid stock solutions were 85 wt% H3PO4, 65 wt% HNO3, and 36–38 wt% HCl. The chromatographic resins used were Dowex 1 × 4, 50–100 mesh (Sigma-Aldrich) and Ni resin (Triskem).

The activity of beta emitters 55Fe and 63Ni in the separated fractions was determined with Quantulus 1220 LSC counter (former Wallac, current Perkin-Elmer). LSC cocktail Ultima Gold uLLT (Perkin-Elmer) was added to each sample prior to LSC measurement (1 ml of sample solution/19 ml of LSC cocktail) and the samples were let stay in cool and darkness one day before the measurement. Chemical yield of Fe and Ni as well as the amount of Co in the purified Fe and Ni fractions was determined with Agilent 4100 MP-AES (micro-plasma atomic emission). The wavelengths used were 259.940 nm, 371.993 nm and 373.486 nm for Fe, 341.476 nm, 352.454 nm and 361.939 nm for Ni and 340.512 nm, 345.351 nm and 350.228 nm for Co. MP-AES calibration standards were prepared with 1000 ppm iron and nickel reference solutions (Romil). The samples were diluted for the measurement with 2% suprapur HNO3 solution (v/v).

Equipment used in the determination of gamma emitters using ISOCS calibration

The ISOCS gamma measurements were carried out with an HPGe Be2020 spectrometer (Canberra Ltd) connected with Inspector 2000 multichannel analyser and Genie 2000 software. The efficiency calibrations were carried out with Geometry Composer v.4.4. The parameters for the efficiency calibrations were the manufacturer given densities and known dimensions of the pieces. Since the densities were constant, the thickness of the sample (0.023–0.024 mm) varied according to weighted mass of the sample.

Each 10 × 10 mm steel sample in the plastic bag was positioned on a sample holder, which was placed at 30 mm distance from the detector in order to avoid coincidence counts from 60Co peaks. Measuring of the sample was continued until at least 10,000 counts were collected into the 60Co 1332.5 keV peak. Due to higher activities of VVER steel samples, they were measured for 5–6 min whereas BWR samples required over 20 min to reach the 10,000 counts limit.

Equipment used in the determination of gamma emitters using standard geometry calibration

Gamma measurements of the steel samples with Canberra GX 8021 HPGe spectrometer were performed by positioning a steel sample in the center of an empty 20 ml LSC vial. The LSC bottle was positioned above the center point of the detector, with a source-detector shield distance of 5 mm. Each sample was measured to receive at least 10,000 counts in the Co-60 peaks (> 4000 s). Dual polynomial fitting option was used for efficiency and energy calibration of the sample spectra.

Testing of method 1 in determination of 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni

The radiochemical method 1 for the determination of 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni was a combination of published articles [6,7,8,9] and previous experience. The procedure was based on a total destruction of the solid sample via an acid digestion, oxidisation of 14C to CO2 and trapping it into NaOH solution, separation of 55Fe and 63Ni from each other via an AG ion exchange resin column and further purification of 63Ni from 60Co via DMG (dimethylglyoxime) chromatography, i.e. Ni-resin. The overall procedure is presented in Fig. 1. Using of two steps in acid digestion was developed during the studies using inactive steel samples in order to first dissolve the steel sample [10] and then finalise oxidisation of carbon to CO2 using a strong oxidising acid, namely perchloric acid. Na2CO3 was added as a carbon carrier. Effectiveness of the oxidisation was tested by spiking the inactive steel samples with 14C standard solution and the yield was measured by analysing the 14C concentrations in absorption bottles two and three (Fig. 2). Details for the separation of Fe and Ni fractions and Ni-fraction purification are presented by Hou et al. [8]. However, during the method development and analysis of activated steel samples, it became clear that method 1 needed modification (ineffective separation of Fe and Ni and presence of Co in Ni fraction). The steps taken for the modification are presented in the Results chapter. The chemical yields were determined using ICP-OES and 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni were measured using LSC.

Testing of method 2 in determination of 55Fe and 63Ni

The preliminary plan was to dissolve the steel samples in concentrated acids and, after hydroxide precipitation of investigated metals, separate Fe and Ni from each other and disturbing matrix with anion exchange. Then Ni fractions from anion exchange would be further purified from Co either by co-precipitating Ni with DMG (traditional method) [8, 11] or by extraction chromatographic column separation with Ni resin (a newer method) [12,13,14]. Actually, the both methods are based on the complexation of Ni by DMG but the procedures are different in practice, direct mixing of sample and DMG solutions in a beaker vs. column separation. The idea of this division was to compare the efficiency of the two methods in separation of Ni from Co. The preliminary separation scheme for 55Fe and 63Ni is presented in Fig. 3. During the analysis of the first sample batch, it was found out that the separation method needed to be modified to improve recoveries of 55Fe and 63Ni as well as decrease the concentration of 60Co in the separated Fe and Ni fractions. The observations of the preliminary method 2 and improved method 2.1 are discussed in the Results section.

Results

Activation calculation results

Table 3 lists the specific activities of the activated steel samples calculated with ORIGEN-S. Uncertainties in calculated activities arise from the uncertainties in exact original material composition, neutron dose, reaction cross sections and decay time. Uncertainties in material compositions were estimated based on the composition measurement method. This means 10% uncertainty for C, Fe, Co, Ni and 25% for N. Total neutron doses (measured using neutron dosimetry) were obtained directly from the power companies and their uncertainty was not available. Uncertainties for reaction cross sections were listed in Table 2. Reaction 13C(n,γ)14C has a much larger uncertainty. However, its cross section is also significantly smaller than in reaction 13N(n,p)14C. Both reactions have been taken into account and their uncertainty has been estimated as a weighted sum. Irradiation history does not take into account maintenance periods during irradiation and end of irradiation for the VVER samples was known only on monthly precision. It was estimated that the irradiation and decay time have an uncertainty of one month. Depending on nuclide half-lives, at maximum this can have an effect of around 2 percent (for 55Fe), whereas for long-lived nuclides 14C and 63Ni the effect is below 0.1 percent.

Table 3 contains also the calculated nuclide-wise propagated uncertainties from the three multiplied input quantities.

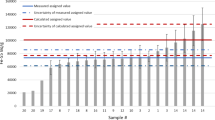

Determination of gamma emitters using standard geometry and ISOCS calibrations and comparison of the results with calculated results

The gamma measurements showed that the only gamma emitter present in the samples was 60Co. Other activation products in steel, such as 54Mn, had already decayed. The measured 60Co concentrations in the VVER steel samples using standard geometry calibrations varied between 68,300 ± 500 and 71,600 ± 500 Bq g−1 whereas corresponding results using ISOCS calibrations varied between 68,500 ± 2000 and 72,800 ± 2100 Bq g−1. The 60Co results for the BWR steel samples varied between 13,700 ± 100 and 16,300 ± 100 Bq g−1 and between 15,800 ± 500 and 16,300 ± 500 Bq g−1, respectively. The results are presented together with the activation calculation results in Figs. 4 and 5. The figures show that the 60Co results using standard geometry and ISOCS calibrations are well comparable, especially for the VVER samples whereas for the BWR samples 2 out of 4 results using the standard geometry calibration vary from the ISOCS results. The 60Co results in VVER samples are well comparable with the calculated results whereas the calculated results of the BWR samples are approximately 16% above the average measured 60Co concentration.

Determination of 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni using method 1.1

The results for 14C, Fe and Ni yields in inactive steel samples using method 1 are presented in Table 4. During 14C spiked tests, increasing the amount of added carbon carrier increased the yield, but the amount was limited by strong formation of CO2 in addition of HNO3 and HCl mixture and leaking of the CO2 via acid addition vial. Therefore, amount of carbon carrier was fixed to 0.1 g of Na2CO3 for both steel types when a relatively constant yield was achieved. 14C yield results show that the average yield with standard deviation for VVER RPV steel samples was 61 ± 3% and for BWR RPV steel samples 24 ± 4%. Significant difference between the BWR and VVER yields is unknown but should be studied further in order to form a possible relation between the yield and the chemical composition of the sample, for example. The chemical yield results for the Fe and Ni analysis are also presented in Table 4. The volume reduction after acid digestion was carried out via hydroxide precipitation for samples VVER_6 to 8 and via evaporation for samples BWR_6 to 8. Two 10 g AG resin column separations for Fe and Ni were tested with different amounts of washing solutions. Also one 20 g AG resin column was tested for BWR_6 sample. However, all the configurations provided good yield results for Ni (> 90%) whereas Fe yields varied from 27 ± 3% down to 0.10 ± 0.01%. The Fe yields varied significantly due to the method adjustments during the analysis of the inactive samples. The Co amounts were less than 1% of the Fe and Ni amounts in the corresponding fractions. However, even small amounts of 60Co in the 55Fe and 63Ni can affect the LSC results.

After the analysis of inactive steel samples the method 1 (Fig. 1) was modified to method 1.1 (Fig. 6) in order to effectively separate Fe from Ni and effectively purify them from Co. The acid digestion and analysis of 14C remained the same in both methods. In order to solve the problem of effective separation of Ni from the high amount of Fe (see Table 1) without increasing the amount of AG resin needed for the separation of Fe from Ni, a decision was made to sacrifice good Fe yield. Since the activated steel samples contained high amounts of stable Fe and 55Fe (according to modelling, see Table 3), a decision was made to purify as small as possible amount of 55Fe with as high as possible purity and high enough signal for the ICP-OES and LSC measurements. Therefore, a calculation was made that approximately 4 mg of Fe would be present in 300 µl of 13 ml acid digested mixture. 4 mg is the amount of Fe carrier added in analysis of 55Fe for example in Ref. [8] since this is also amount of Fe that 10 g of AG resin can effectively absorb. 300 µl Fe-fraction was then evaporated to dryness, dissolved into 9 M HCl and purified from Ni and Co using 10 g of AG resin. If needed, the solution passing through the column and 4 M HCl wash containing some Ni could be added into Ni-fraction. However, the Ni amount in the 300 µl fraction was estimated to be very low and thus not needed. After elution of Fe from the AG resin using 0.5 M HCl, the solution was evaporated to dryness, dissolved into 1 M H3PO4 and 1 ml of Fe-fraction was mixed with 10 ml LSC cocktail. Rest of the Fe-fraction was reserved for the yield measurements using ICP-OES. Ni was separated from the large amount of Fe in the main 13 ml of acid digested mixture (minus 300 µl Fe-fraction) using an ammoniumhydroxide precipitation in pH 4-5, in which the Fe was effectively precipitated as a hydroxide whereas Ni remained in the solution (74 ± 4%) according to Choi et al. [15]. pH was adjusted with careful addition of 25% NH4OH. The Fe-precipitate was separated from the Ni containing supernatant using a centrifuge (5 min, 2500 rpm). The supernatant was then evaporated to near dryness and dissolved into 9 M HCl. Some residue remained undissolved. The residue did not originate from the acid digestion, which was complete, but may originate from the NH4OH addition. Further studies are needed for the composition of the precipitate which may lower the Ni yield. The solution was passed through a 10 g AG resin column in order to remove any residual Fe, which could disturb Ni-resin separations. AG resin also removed some 60Co from the Ni-fraction. The passed through solution and 4 M HCl wash were combined, evaporated to near dryness and dissolved into 1 M HCl and 1 M NH4Ctr. The pH of the solution was adjusted to pH 8-9 using NH4OH prior to loading of the Ni-fraction into the 0.5 g Ni-resin column. After washing of the Ni containing DMG precipitate, Ni-fraction was eluted using 3 M HNO3. In order to verify the effectiveness of the Ni purification from 60Co, the eluate was measured using gamma spectrometry. The results showed significant presence of 60Co and thus, the Ni-resin purification was repeated according to Eriksson et al. [13]. The Ni-fraction was measured again and the gamma spectrometric results showed efficient removal of 60Co. Therefore, two consecutive Ni-resin purifications were added into the method 1.1. Purified Ni-fraction was evaporated to 1-2 ml, the volume was determined, 1 ml of Ni-fraction was mixed with 10 ml of HiSafe 3 liquid scintillation cocktail prior to LSC measurements. Rest of the Ni-fraction was reserved for yield measurements using ICP-OES.

The Fe and Ni yield results when using method 1.1 are shown in Table 5. The Fe yields in VVER samples varied from 0.9 to 1.0% and for BWR samples from 0.4 to 0.7%. The yields are low but the 55Fe signals in LSC measurements (500–1400 cpm) were well above background (approximately 30 cpm). Ni yields for VVER samples varied from 14 to 32% and BWR samples from 24 to 29%. The yields are relatively low but still the 63Ni signals in LSC measurements (2013–160,000 cpm) were well above background (approximately 40 cpm). No significant amounts of Co was measured in the Fe and Ni fractions.

Determination of 55Fe and 63Ni using method 2.1

The differences in chemical composition between the two steel types were first seen in the dissolution of the samples. BWR steel samples dissolved easily to HNO3, but VVER steel samples did not dissolve without adding HCl to the sample and HNO3 mixture.

During the analysis of inactive steel samples BWR-_1-2 and VVER_1-2, the method 2 was slightly adjusted by increasing the amount of used ion exchange resin for ensuring the adequate capacity of the resin in respect to high iron concentration in the steel samples. During the first separations with a smaller resin amount, a yellow colour due to presence of iron occurred in nickel and cobalt fractions. Also it was decided to use 3 M H3PO4 instead of 1 M HCl in the preparation of the LSC samples from the purified 55Fe and 63Ni fractions. This change was necessary for obtaining colourless LSC samples and not having a quenching effect in LSC measurements due to colour in the samples [12].

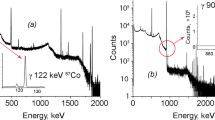

However, bigger changes were needed in the method 2 for increasing the low radiochemical yield of Ni (Table 6) and improving the separation of 55Fe and 63Ni from 60Co. LSC and gamma measurements of the first separated 55Fe and 63Ni fractions from the activated steel samples VVER_a-b and BWR_a-b revealed the presence of 60Co as extensive amounts in the LSC samples (Fig. 7). Obviously, the activated steel samples contained so high amount of 60Co that the separation capacity of the resin amounts used for separating 60Co from 55Fe and 63Ni was not enough for these steel samples. The resin amounts used per steel sample were 30–60 ml for Dowex 1 × 4 and 0.7 grams for Ni resin.

LSC spectra of an iron fraction VVER_a separated according to method 2. Left curve: before extra anion exchange step in acetone media, note the shoulder on the right side of 55Fe peak caused by 60Co in the iron fraction. Right curve: the same iron fraction after anion exchange step in acetone media, after which there are no traces from 60Co left

Another reason for low yields of 63Ni and presence of 60Co in the separated nickel fractions might be the addition of stable Co carrier in the beginning of the analysis. According to Lee et al. [16], and Warwick and Croudace [12], the stable Co carrier should be added only after the separation of 63Ni. Similar to radioisotope 60Co, also the stable isotope 59Co interferes with the separation of 63Ni by complexing with DMG as well. The yields of 63Ni were varying according to the steel type and the method used, from 31 to 97% among the activated steel samples VVER_a-d and BWR_a-d (Table 6). These were analysed either by first using the method 2 and later an extra anion exchange step in acetone media (this will be described in the next paragraph), or directly by method 2.1. The radiochemical yields for 63Ni were at the satisfactory level regarding to analysis of high-activity steel samples where the loss of analytes is not so critical considering detection limits etc., but the yield could still be improved. It would be useful to test whether the yield of 63Ni increases if the Co carrier is added after the radiochemical separation of 63Ni by DMG complexation (either as such or as in Ni resin), or if it is not added at all.

The observed presence of 60Co in the LSC spectra of the separated 55Fe and 63Ni fractions lead to testing another option for separating Fe, Ni, and Co, instead of the anion exchange procedure in method 2 and the following purification of 63Ni either by Ni resin or DMG precipitation. A previous study by Hazan and Korkisch [17] had proved that Fe, Ni, and Co can be efficiently separated from each other by anion exchange when it is performed in acetone and HCl media. When the sample is loaded to an anion exchange column in 9:1 mixture of acetone and 6 M HCl and the elution rate is kept constantly low, 0.3–0.4 ml min−1, then Fe is first eluted from the column with the loading solution. After switching to wash solution of 7:3 mixture of acetone and 2 M HCl, then Ni is eluted from the column. With appropriately selected elution volumes and the low flow rate, Co remains in the resin column. This treatment was first tested to the activated steel samples BWR_a-b and VVER_a-b after their separation according to method 2. According to gamma spectrometric and LSC measurements of the 55Fe and 63Ni fractions after acetone media ion exchange treatment, there was no 60Co present in the separated samples anymore (Fig. 7). Therefore, for the yet unanalysed steel samples, previous anion exchange, DMG co-precipitation and Ni resin separation were replaced with a single anion exchange separation in acetone media. This improved method 2.1 is depicted in Fig. 8.

The difference between performances of the two methods (method 2 and later anion exchange in acetone media step, and method 2.1 directly) is seen in the recovery values in Table 7. 55Fe yield was 21–66% while using method 2 with later anion exchange step in acetone media (samples VVER_a-b and BWR_a-b) and with method 2.1 the 55Fe yield increased to 89–96%. 63Ni yield was not changing as straightforward as 55Fe yield: VVER steel samples had even lower 63Ni yield level after the method change (31% and 45%), compared to the 63Ni yield before the change (55% and 76%). On the other hand, BWR steel samples had significantly higher 63Ni yield with method 2.1 (92% and 97%) compared to method 2 (31% and 52%) with later anion exchange in acetone media. The yield of 60Co is significantly lower in samples analysed by method 2.1 (1.5–2.2%, in Fe and Ni fractions, respectively) compared to samples analysed by method 2 and extra acetone media anion exchange (11–32%, in Fe and Ni fractions, respectively). It can be concluded that the implementation of method 2.1 mainly increased the yields of 55Fe and 63Ni, and reduced the amount of 60Co in the 55Fe and 63Ni fractions to acceptable level. It was also observed again that the steel types BWR and VVER have remarkable differences in composition and chemical behavior.

Comparison of measured 14C, 55Fe and 63Ni and calculated values

As discussed earlier, the chemical yield of 14C was estimated using inactive samples spiked with 14C standard (see Table 4 e.g. 61% for VVER and 24% for BWR). Therefore, the 14C activity concentration results were corrected using the corresponding experimentally estimated yields. The results are shown in Figs. 9 and 10 together with the activation calculation results in the VVER and BWR steel samples. Additionally, the figures also show results for the measured 14C concentrations assuming 100% yields. The figures show comparable results between the measured 14C values of both steel types and additionally comparable results with the activation calculation results when 100% yield is assumed. However, the results, which were corrected using analytically estimated yields, are within the same order of magnitude compared with the activation calculation results.

The measured 55Fe and 63Ni results in VVER steel samples are shown together with the activation calculation results in Figs. 11 and 12. The 55Fe concentrations in the VVER steel samples using method 2.1 varied between 118,200 ± 16,700 and 135,400 ± 19,100 Bq g−1 whereas corresponding results using method 1.1 were between 137,600 ± 12,600 and 147,300 ± 13,500 Bq g−1. Even though method 2.1 gave in general higher results for 55Fe concentrations, all the results are comparable within the uncertainties. Comparison of the measured results to the calculated result show, that all the measurements gave on average 35% higher 55Fe concentrations compared to the calculated results. However, method 2.1 results are comparable with the calculated results within the uncertainties, but method 1.1 results are also within the same order of magnitude.

The 63Ni concentrations in the VVER steel samples using method 2.1 were between 52,600 ± 7500 and 76,100 ± 10,800 Bq g−1 whereas corresponding results using method 1.1 were between 64,700 ± 7000 and 109,200 ± 11,800 Bq g−1. The 63Ni results show larger variation compared to 55Fe results having over twice the amount of 63Ni concentration in the highest result compared to the lowest result. Comparison of the measurement results with the calculated results show that the results are comparable within the uncertainties except for samples 5 and 6, which, nevertheless, are within the same order of magnitude.

The measured 55Fe and 63Ni results in BWR steel samples are shown together with the activation calculation results in Figs. 13 and 14. The 55Fe concentrations in the BWR steel samples using method 2.1 were between 123,400 ± 17,500 and 278,200 ± 39,400 Bq g−1 whereas corresponding results using method 1.1 were between 99,200 ± 15,800 and 243,200 ± 22,200 Bq g−1. The result show large variation having almost three times the 55Fe amount between the lowest and the highest result. Comparison of the measured results with the calculated results show that the averaged measured 55Fe concentration is approximately 35% higher than the calculated results. However, all the results are within the same order of magnitude.

The 63Ni concentrations in the BWR steel samples using method 2.1 were between 5900 ± 800 and 6400 ± 800 Bq g−1 whereas corresponding results using method 1.1 were between 3600 ± 400 and 5900 ± 600 Bq g−1. The result show one clear outlier (sample 5) whereas all the other results are comparable within the uncertainties. The measured results also correlate well with the calculated result.

Discussion

The analysis of 60Co in the VVER and BWR steel samples using standard geometry and ISOCS calibrations showed comparable results. The measurement results for VVER steel samples were also comparable with the calculated results whereas the BWR steel results are little bit lower (on average 16%) than the calculated results. However, the measured results were approximately within the lower uncertainty limit of the calculated result and the short half-life of 60Co (5 y) may have an effect on the results. It can be concluded, that for strong gamma emissions, such as the 1173 keV and 1333 keV gamma emissions of 60Co, both calibration methods can be utilised for producing comparable results. However, gamma emissions with lower energies might be effected by self-absorption especially in thick samples. Therefore, similar exercise comparing the two calibration methods would be interesting with thicker samples and low energy gammas.

The analysis of 14C was challenged by the unknown reason for the difference of the experimentally determined yields in the VVER and BWR steel samples. Additionally, the results showed that assumption of 100% yield for both steel types gave comparable results with the calculated 14C concentrations. Therefore, 14C analysis should be validated using another technique, such as with an oxidizer or a pyrolyser, or with an intercomparison exercise.

The 55Fe and 63Ni analysis in the steel samples using methods 1.1 and 2.1 showed consistent results for 55Fe analysis in VVER steel samples and 63Ni analysis in BWR steel samples whereas results varied for 55Fe analysis in BWR steel samples and 63Ni analysis in VVER steel samples. Therefore, it can be concluded that the analysis of 55Fe and 63Ni are affected by the chemical composition of the studied material and analysis of several replicates are needed. However, the results were within the same order of magnitudes, which may well be a good enough result for the decommissioning purposes. The comparison of the measured 55Fe results to the calculated results showed on average 35% higher concentrations for both VVER and BWR steel samples whereas the measured 63Ni concentrations were comparable within the uncertainties of the calculated results for both VVER and BWR steel samples.

Improvement needs for the radioanalytical methods

As the results have shown, the analysis of DTM is difficult but comparison of two analytical methods and also their comparison to calculated results have given validity to the developed methods 1.1 and 2.1. However, the methods could be further improved. Anion exchange in the acetone and HCl media adopted to method 2.1 from Korkisch and Hazan [17] proved to be efficient in separating 60Co, 55Fe, and 63Ni from each other in the steel samples having naturally high iron content. However, the method is very slow, anion exchange requiring one long working day, and high volumes of resin, acetone and HCl are consumed. A faster method is needed that would consume less reagents than in method 2.1, but which would still produce purified fractions of 55Fe and 63Ni free from 60Co, preferably with reasonable radiochemical yields.

Method 1.1 sought to be a fast and resource-efficient way to analyse DTM. However, successful use of this method requires large amounts of both 55Fe and 63Ni to be present in the samples, since the yields are low. In cases, when the concentration of the analytes of interest are low, higher yields are compulsory. Additionally, higher yields may be needed for the analysis of 59Ni.

On the other hand, a requirement of short analysis time and complete purification of 55Fe and 63Ni from 60Co with high radiochemical yield, may be unnecessary in many situations where the exact activity concentration of DTM radionuclides is not needed. Instead, a more rapid separation method with tolerable amount (to be determined practically) of 60Co present in the separated fractions of 55Fe and 63Ni and the radiochemical yield being just high enough for enabling the detection, might be enough for providing the acceptable order of magnitude of the DTM concentration in the sample matrix. This should be considered in case of high number of samples coming from decommissioning facilitie to be analysed rapidly, containing adequately high concentration of DTM radionuclides.

Uncertainties of the measured and calculated activity concentration results

The uncertainty of experimentally determined activity concentration includes several uncertainty sources, the most important ones including balance uncertainty from weighing in different phases of analytical procedure, concentration uncertainty from ICP-AES/OES measurements of the stable isotopes, and radioactivity uncertainty from gamma and LSC measurements. The resulting uncertainties of the activity concentration results were up to 18% for 14C, 2–3% for 60Co, and 10 to 15% for 55Fe and 63Ni. Gamma measurements produced lower total uncertainties for the activity concentrations compared to LSC due to the non-destructive analysis and high gamma emissions of the samples.

The uncertainties of the calculated results include also experimental uncertainties, since one of the inputs for the calculations is the chemical composition of the original material. Additionally, uncertainties arise from the irradiation time, neutron dose, reaction cross sections and decay time. Overall, the calculated activity concentrations had uncertainties of 10–13% for 55Fe, 60Co and 63Ni and 25% for 14C. The assumed uncertainty of 10 percent is relatively high for a measured value, but the aim was to also take into account possible heterogeneity in the material microstructure.

Conclusions

The analysis of gamma emitters is a non-destructive determination technique and the measured 60Co results underlined their concept of being easy to measure. However, further studies are needed for low energy gamma or x-ray emitters (e.g. 59Ni).

Empirical determination of 14C yield showed higher yield results for VVER steel compared to BWR steel. The reason is yet unknown and should be studied further. However, the measured results were well comparable with the calculated results.

In general, the obtained experimental values using the methods 1.1 and 2.1 were well comparable. Variations occurred both in the 55Fe and 63Ni results without correlation to the steel type or activity level, e.g. small variation of 55Fe results in VVER steel and 63Ni results in BWR steel versus larger variation of 63Ni results in VVER steel and 55Fe in BWR steel. The calculated 63Ni results corresponded well with the experimental values, whereas the 55Fe and 60Co results had more difference between experimental and calculated results.

Even though the article focused on method development and comparison of experimental results with calculated results, extrapolation of the results to high dose rate components is an interesting topic. The radioanalytical methods presented here can be applied to high dose rate samples, but ALARA principle should be the driving force in selection of the sample size, building of radiation shielding and justification of the amount of analysis due to the hands on nature of the radioanalytical methods.

The DTM radioanalytical method development work in other decommissioning materials and the combination of experimental and computational analyses is continued in other projects, providing further information about the performance of different radioanalytical methods as well as the properties of different decommissioning matrices.

References

IAEA (1998) Radiological characterization of shut down nuclear reactors for decommissioning purposes, IAEA Technical Report Series 389, Vienna

X-5 Monte Carlo Team (2003) MCNP—a general Monte Carlo N-particle transport code, Version 5, Los Alamos National Laboratory, LA-UR-03-1987

Bowman SM (2011) SCALE 6: comprehensive nuclear safety analysis code system. Nucl Technol 174:126–148

https://www.vttresearch.com/services/low-carbon-energy/nuclear-energy/decommissioning-of-finlands-first-nuclear-reactor. Accessed 26 June 2019

Paul Scherrer Institute PSI and the Internation Atomic Energy Agency IAEA (Nuclear Data Section), TALYS-based evaluated nuclear data library TENDL, https://tendl.web.psi.ch/tendl_2017/tendl2017.html. Accessed 22 Aug 2019

Hou X (2007) Radiochemical analysis of radionuclides difficult to measure for waste characterization in decommissioning of nuclear facilities. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 273:43–48

Hou X (2005) Rapid analysis of 14C and 3H in graphite and concrete for decommissioning of nuclear reactor. Appl Radiat Isot 62:871–882

Hou X, Frosig Ostergaard L, Nielsen SP (2005) Determination of 63Ni and 55Fe in nuclear waste samples using radiochemical separation and liquid scintillation counting. Anal Chimica Acta 535:297–307

Hou X, Frosig Ostergaard L, Nielsen SP (2007) Determination of 36Cl in nuclear waste from reactor decommissioning. Anal Chem 79:3126–3134

Kazuhiro S (2015) Determination of trace elements in steel using the Agilent 9700 ICP-MS. Application note 5991-6116EN

Puukko E, Jaakkola T (1992) Actinides and beta emitters in the process water and ion exchange resin samples from the Loviisa power plant. (No. YJT–92-22). Helsinki, Finland: Nuclear Waste Commission of Finnish Power Companies

Warwick P, Croudace I (2006) Isolation and quantification of 55Fe and 63Ni in reactor effluents using extraction chromatography and liquid scintillation analysis. Anal Chim Acta 567:277–285

Eriksson S, Vesterlund A, Olsson M, Ramebäck H (2013) Reducing measurement uncertainty in 63Ni measurements in reactor coolant water high in 60Co activities. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 296:775–779

Taddei M, Macacini J, Vicente R, Marumo J, Sakata S, Terremoto L (2013) Determination of 63Ni and 59Ni in spent ion-exchange resin and activated charcoal from the IEA-R1 nuclear research reactor. Appl Radiat Isot 77:50–55

Choi K-S, Lee CH, Im H-J, Yoo JB, Ahn H-J (2017) Separation of 99Tc, 90Sr, 59,63Ni and 94Nb from activated carbon and stainless steel waste samples. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 314:2145–2154

Lee C, Martin JE, Griffin HC (1997) Optimization of Measurement of 63Ni in Reactor Waste Samples using 65Ni as a tracer. Appl Radiat Isot 48:639–642

Hazan I, Korkisch J (1965) Anion-exchange separation of iron, cobalt and nickel. Anal Chim Acta 32:46–51

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT). The research was funded by KYT 2018 (Finnish Research Programme on Nuclear Waste Management 2015–2018). The authors would also like to thank Fortum Power and Heat and Teollisuuden Voima Oyj for their collaborative actions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Leskinen, A., Salminen-Paatero, S., Räty, A. et al. Determination of 14C, 55Fe, 63Ni and gamma emitters in activated RPV steel samples: a comparison between calculations and experimental analysis. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 323, 399–413 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-019-06937-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-019-06937-4