Abstract

The meaning ‘to allow’ is expressed in Hindi-Urdu by the verb de-na ‘give’ with an oblique infinitive complement, which I argue is syntactically as well as semantically ambiguous. It has a biclausal control analysis, meaning ‘allow X to do A’, as well as an Exceptional Case Marking (ECM) complement with the meaning ‘allow A to happen’. The complements are smaller than finite CP and larger than the non-clausal causative complement, and the ECM complement is smaller than the control complement. I offer syntactic arguments for the syntactic ambiguity associated with the two meanings; where the control reading is unavailable, the ECM structure and meaning are available, sometimes by coercion from the context. The modal meaning associated with the control structure suggests that modals do not occur only in ECM/Raising constructions. The arguments are couched in minimalist syntactic terms, opening up a cross-theoretical dialogue with Butt’s (1995) analysis in Lexical-Functional Grammar (LFG) terms of the permissive as a complex predicate in argument structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

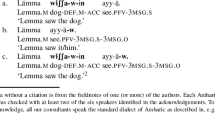

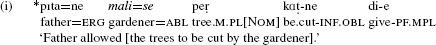

Abbreviations: ABL—Ablative, ACC—accusative, CP—Conjunctive participle, DAT—dative, ERG—ergative, GEN—genitive, F—feminine, IMPER—imperative, IMPF—imperfective, INF—infinitive, M—masculine, NOM—nominative, OBL—oblique, PF—perfective, PL—plural.

The permissive differs from other control complements because there is no postposition on the infinitive clause (see the following note). Postpositions are known to block agreement in Hindi-Urdu (HU). So the permissive construction also allows optional long distance agreement with the embedded clause nominative argument (cf. Bhatt 2005). Agreement is one of Butt’s (1995) arguments for monoclausality. Bhatt (2005) argues that this kind of agreement is associated with a reduced or restructured embedded clause, so the combination of infinitive and matrix is in effect one clause for the purposes of agreement. But note that the ECM structure (4b) has a projected subject, and is not a reduced clause. So I will represent (4b) ECM clauses as fully biclausal, pace Bhatt (2005), with a subject in the embedded clause, and optional agreement.

For example, the complex predicate mazbur kar-na ‘force’ selects =ke liye ‘for’ or =par ‘on’ for the infinitive complement, while vivash kar-na ‘oblige, force, put the screws on’ selects =ko ‘dative’ on both the indirect object and the complement clause (Bahl 1979:34–35); see also Bahl (1974:210–212) for razi kar-na ‘prevail on someone (=ko ‘dative’) to do something (=par/ke liye ‘on/for’)’.

Evidence for grammatical dative-marked PRO in Icelandic is found in Sigurðsson (2008), along with some examples which are not fully grammatical. Icelandic may not be a clear exception to the ∗(PRO-Dat) condition.

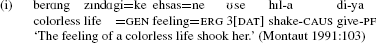

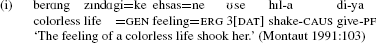

Butt (2013:Sect. 3.2.4) interprets cah-na ‘want’ as a volitional kind of wanting, which takes a =ne ‘ergative’ subject in the perfective. There is an important difference between my assumptions about =ne and hers (Butt and King 2004); I agree with Montaut (1991:103) that non-volitional subjects may be marked with =ne, while Butt and King associate the semantic role of agent with =ne.

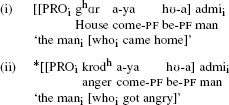

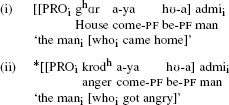

Another syntactic environment in which the ∗PRO-Dat condition is found is participle modifiers. The participles have a null argument corresponding to the modified head. If the dative condition holds, this null category must be PRO. This structure bears on arguments for a clausal complement for the ECM structure in Sect. 3.

See Subbarao (2012:292–294 and Appendix 8.3) for examples of South Asian languages which do or do not have participles like (ii).

The conditions for anaphoric binding are complicated by several factors. The simplex anaphor may be used logophorically, especially in the first and second person. Also, as Butt points out (2013:Sect. 3.2.1), there is an emphatic use, but it is without case and thus not to be confused with the anaphor. There are disagreements in speakers’ judgments about whether the causee can bind a possessive reflexive, summarized from several different sources in Davison (1999:415). But the default interpretation is that there is a c-commanding subject antecedent.

This structure could have been represented as Raising to Object, without changing my arguments. The differences between the ECM and Raising to Object analyses are not relevant to the issues discussed here.

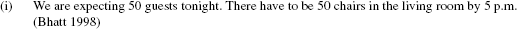

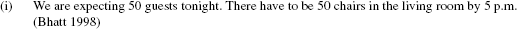

Bhatt (1998) argues on the basis of sentences like (i) that there need not be a projected locus of obligation, which is syntactically the subject of a deontic modal ‘have to’.

The caterer in this case is the locus of obligation.

Subbarao (1984:167) discusses sentences like example (28) which have three syntactic analyses, a propositional complement, which I am assuming here, and two participle modifier constructions, controlled by the matrix and embedded subjects.

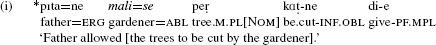

Additional evidence that this dative marking is the effect of the ECM verb, and not the complement verb, can be seen in a version of (23) that projects the optional agent with =se ‘ablative’, not =ko ‘dative’. The sentence is ungrammatical:

See Rivero et al. (2010) for a discussion of two different languages which have different syntactic structures to express circumstantial necessity.

The Sanskrit verb √dā ‘give’ has the meaning ‘allow’ with an infinitive complement and a dative locus of permission. Unfortunately the example which is cited in Apte (1958, Vol. II:507) lacks an overt indirect object. It is understood, and would be dative if overt (Frederick Smith, p.c.).

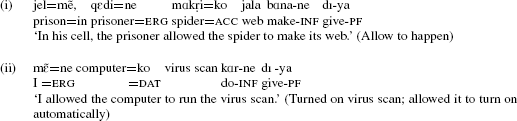

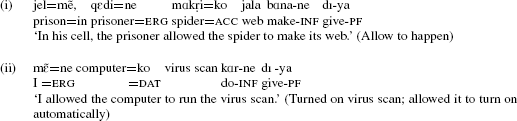

There are differences in what counts as a locus of permission. An animate spider would not (i), while a computer, which is strictly speaking inanimate, might (ii):

Miriam Butt notes that German lassen ‘let’ has these two interpretations, but both are associated with the accusative-infinitive structure, probably an ECM structure under my assumptions. The ‘allow X to do’ interpretation has an accusative locus of permission, while in the ‘allow to happen’ interpretation the accusative DP is not a locus of permission. Another verb, erlauben ‘give permission to’, seems to have only the ‘allow to do’ meaning; it requires a dative locus of permission and is a control structure.

There is a third argument, based on the fact that the permissive allows long-distance agreement with the infinitive object, while the instructive does not (Butt 1995:52). This is a purely mechanical consequence of the fact that the instructive selects a postposition on its complement, and the permissive does not. The oblique infinitive in the permissive is an unusual property.

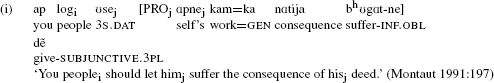

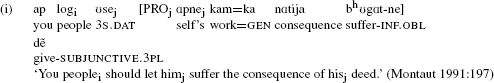

Some additional support for my view comes from Montaut (1991:197ff), who discusses the role of contextual salience in assigning a referent to the reflexive possessive apna.

References

Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. economy. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 31: 435–483.

Apte, Viman Shivram. 1958. Practical Sanskrit-English dictionary, Vol. II. Poona: Prasad Prakashan.

Bahl, Kali Charan. 1974. Studies in the semantic structure of Hindi, Vol. I. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Bahl, Kali Charan. 1979. Studies in the semantic structure of Hindi, Vol. II. New Delhi: Manohar.

Bahri, Hardev. 1992. Learner’s Hindi-English dictionary. Delhi: Rajpal and Sons.

Bhatt, Rajesh. 1998. Obligation and possession. In Proceedings of the UPenn/MIT workshop on argument structure and aspect, ed. Heidi Harley, 21–40. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Bhatt, Rajesh. 2005. Long distance agreement in Hindi-Urdu. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 23: 757–807.

Bhatt, Rajesh. 2006. Covert modality in non-finite clauses. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Butt, Miriam. 1995. The structure of complex predicates in Urdu. Stanford: CSLI.

Butt, Miriam. 1998. Constraining argument merger through aspect. In Complex predicates in non-derivational syntax, syntax and semantics 30, eds. Erhard Hinrichs, Andrea Kathol, and Tsuneko Nakazawa, 73–113. San Diego: Academic Press.

Butt, Miriam, and Tracy Holloway King. 2004. The status of case. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. V. Dayal, and A. Mahajan, 153–198. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Butt, Miriam. 2013. Control vs. complex predicates: Identifying non-finite complements. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. doi:10.1007/s11049-013-9217-5.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davison, Alice. 1999. Hindi. In Lexical anaphors and pronouns in selected South Asian languages, eds. Barbara Lust, Kashi Wali, James W. Gair, and Karumuri V. Subbarao, 397–470. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Davison, Alice. 2001. Long distance anaphors in Hindi-Urdu: Issues. In Long distance anaphora, eds. Peter Cole, James C.-T. Huang, and Gabriella Hermon, 47–82. Irvine: Academic Press.

Davison, Alice. 2004. Structural case, lexical case and the verbal projection. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. Veneeta Dayal, and Anoop Mahajan, 99–225. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Davison, Alice. 2008. Obligatory control and the role of case and agreement. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 1(1). Online: http://jsal-journal.org.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2010. Hindi pseudo incorporation. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29: 123–167.

Gurtu, Madhu. 1992. Anaphoric relations in Hindi. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

Hacquard, Valentine. 2011. Modality. In International handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maierhorn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hornstein, Norbert. 1999. Movement and control. Linguistic Inquiry 30: 69–96.

Kachru, Yamuna, and Tej Bhatia. 1975. Evidence for global constraints: The case for reflexivization. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 5: 42–73.

Khokhlova, Ludmila. 2003. Infringement of morphological and syntactic operations’ pairing in ‘second causative’ formation. Indian Linguistics 64(1).

Kratzer, Angelika. 1981. The notional category of modality. In Words, worlds, and contexts: New approaches to word semantics, eds. Hans-Jurgen Eikmeyer, and Hannes Rieser, 38–74. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. Modality. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, eds. Arnim von Stechow, and Dieter Wunderlich, 639–650. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Lasnik, Howard, and Mamoru Saito. 1991. On the subject of infinitives. In Papers from the 27th regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, eds. Lise M. Dobrin, Lynn Nichols, and Rosa M. Rodriguez, 324–343. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

McCawley, James. 1993. Everything that linguists have always wanted to know about logic (but were ashamed to ask). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mohanan, Tara. 1994. Argument structure in Hindi. Stanford: CSLI.

Montaut, Annie. 1991. Aspects, voix et diathèses en Hindi modern. Louvain-Paris: Éditions Peeters.

Perlmutter, David. 1970. The two verbs begin. In Readings in English transformational grammar, eds. Roderick A. Jacobs, and Peter. S. Rosenbaum, 107–119. Waltham: Ginn and Co.

Portner, Paul. 2009. Modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Postal, Paul. 1974. On raising: One rule of English grammar and its theoretical implications. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2008. Verb meaning and the lexicon: A first-phase syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rivero, Maria Luisa, Ana Arregui, and Ewelina Frąckowiak. 2010. Variation in circumstantial modality: Polish vs St’át’imeets. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 704–714.

Rosenbaum, Peter. 1967. The grammar of English predicate complement constructions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sigurðsson, Halldór. 2008. The case of PRO. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26: 403–450.

Subbarao, Karumuri V. 1984. Complementation in Hindi syntax. Delhi: Academic Publications.

Subbarao, Karumuri V. 2012. South Asian languages: A syntactic typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sweetser, Eve. 1990. From etymology to pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wurmbrand, Susi. 1999. Modal verbs must be raising verbs. In The proceedings of WCCFL 18, eds. Sonya Bird, Andrew Carnie, Jason D. Haugen, and Peter Norquest, 599–612. Cambridge: Cascadilla Press.

Wurmbrand, Susi. 2007. How complex are complex predicates? Syntax 10: 245–288.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to two anonymous reviewers, Miriam Butt, Gillian Ramchand, Rajesh Bhatt, Peter Hook, Liudmila Khokhlova and Thomas McFadden. They have all made valuable suggestions which I have tried to incorporate into this version of the paper, but they are not responsible for the results! I am grateful to Philip Lutgendorf for making me aware of the songs which I quoted as examples of the permissive. Thanks also to the participants at the Finiteness in South Asian Languages conference (FiSAL) at University of Tromsø, June 9–10, 2011, especially to the organizers Sandhya Sundaresan and Thomas McFadden, who also played a major role in preparing this volume.

Thanks very much to the following for generously contributing their judgments on Hindi and Urdu sentences: Archna Bhatia, Sami Khan, Pranav Prakash, Rajiv Ranjan and Richa Srishti. Thanks also to my colleague Solveig Bosse for German judgments. As usual, thanks to A. Azar, D.J. Berg, S. Cassivi, A. Comellas, Y. Romero, D. Capper and M. Yao. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the January 2011 SALA meeting at CIIL Mysore, and the FASAL meeting at University of Massachusetts, March 2011. Many thanks to the audiences for their comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davison, A. Non-finite complements and modality in de-na ‘allow’ in Hindi-Urdu. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 32, 137–164 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9224-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9224-6