Abstract

The Center for Financial Stability (CFS) has initiated a new Divisia monetary aggregates database, maintained within the CFS program called Advances in Monetary and Financial Measurement (AMFM). The Director of the program is William A. Barnett, who is the originator of Divisia monetary aggregation and more broadly of the associated field of aggregation-theoretic monetary aggregation. The international section of the AMFM web site is a centralized source for Divisia monetary aggregates data and research for over 40 countries throughout the world. The components of the CFS Divisia monetary aggregates for the United States reflect closely those of the current and former simple-sum monetary aggregates provided by the Federal Reserve. The first five levels, M1, M2, M2M, MZM, and ALL, are composed of currency, deposit accounts, and money market accounts. The liquid asset extensions to M3, M4-, and M4 resemble in spirit the now discontinued M3 and L aggregates, including repurchase agreements, large denomination time deposits, commercial paper, and Treasury bills. When the Federal Reserve discontinued publishing M3 and L, the Fed stopped providing the consolidated, seasonally adjusted components. Also the Fed no longer provides the interest rates on the components. With so much of the needed component quantity and interest-rate data no longer available from the Federal Reserve, decisions about data sources needed in construction of the CFS aggregates have been far from easy and sometimes required regression interpolation. This paper documents the decisions of the CFS regarding United States data sources at the present time, with particular emphasis on Divisia M3 and M4.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See The Federal Reserve Discontinuation Memo on M3 and its Components.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/current/default.htm. See page 3, line 32 of the H.8 Survey for the seasonally adjusted levels of large time deposits.

http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/mspd.htm. There is no easily downloadable time series data for the level of Treasury bills from the MSPD. The authors can provide that series on request to simplify other efforts to replicate the data.

http://www.newyorkfed.org/xml/gsds_finance.html, under the tab “Financing.”

http: www.federalreserve.gov/releases/cp/volumnestats.htm. See the Data Download Program for historical survey data.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/. The data are taken on a quarterly basis in the Z.1 survey.

A description of these changes can be found here: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/cp/about.htm.

Otherwise a potential replicator will have to wade through monthly scanned documents back to 1967.

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/quote?ticker=IREPUSOA:IND As of the most recent revision of this paper, Bloomberg no longer provides the AM or PM rates for free online, but through its subscription service at a Bloomberg Terminal computer.

Institutional money-market funds used to be a part of simple-sum M3, and are not included in the “old” M2 definition. Currently they are used in MZM and M2-ALL.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/fof/DisplayTable.aspx?t=l.208. See “description” for note on bankers’ acceptances.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/aggreg/swdata.html. As of the writing of the most recent revision of this paper the St. Louis Federal Reserve has suspended its monthly release on retail sweeps.

There are two possible methods of computing year-over-year Divisia growth rates: (1) the Divisia weights could be based upon the average of the components’ expenditure shares between the contemporaneous observation and the one-year lagged observation, or (2) the Divisia index could be chained monthly to produce the level index series, and then the year-over-year growth rates could be computed from the levels series, as advocated by Diewert (1999). We use the latter procedure, since that procedure more closely approaches the continuous-time share weighting and hence produces a higher quality index. We use the year-over-year convention only to produce growth rates. We do not use that approach to produce the levels series.

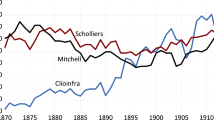

Divisia M2 is not included on the same graphs as the even more informative broad Divisia monetary aggregates, DM3, DM4-, and DM4. While the broad aggregates share common information and components with DM2, the zero weight imputed to monetary components not in M2, such as large time deposits, repurchase agreements, commercial paper, and T-Bills, produces a chasm of difference between simple sum and Divisia, not reflected by M2 figures. We provide the M2 aggregates in Fig. 4, as a comparison of Divisia versus simple sum, only to demonstrate the stronger evidence from Fig. 2’s broad Divisia monetary aggregates in studying the Great Recession and current conditions. The most important information is in the broad Divisia monetary aggregates. Simple-sum broad aggregates are no longer available from the Federal Reserve and are not being supplied by the CFS, because of the extreme distortion in weights caused by simple-sum aggregation over distant substitutes for money and since the Federal Reserve no longer supplies the consolidation of components needed for simple-sum stock aggregation.

The linear regression without a constant estimate follows the procedures outlined later in this paper for the estimation of the interest rate levels of repurchase agreements, the levels of commercial paper, and large time deposits. The coefficient of estimation was estimated at 2.9723, using the overlapping survey period of October 2001 to March of 2006, and the survey switch occurred in October 2001.

A full description of the differences between the “old” and “new” structure surveys can be found at this website: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/cp/about.htm.

References

Anderson R, Buol J (2005) Revisions to User Costs for the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Monetary Services. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 87(6):735–749

Anderson RG, Jones BE (2011) A comprehensive revision of the US monetary services (Divisia) indexes. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 93(5):235–59

Anderson RG, Rasche RH (2001) Retail Sweeps Prorams and Bank Reserves 1994–1999. Federeal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 83(1):51–72

Anderson RG, Jones BE, Nesmith T (1997) Building New Monetary Services Indexes: Concepts, Data, and Methods. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 79.1:53–82

Bankrate.com (2012) Track economic index trends and graph financial industry rates. Retrieved from http://www.bankrate.com/funnel/graph/

Barnett W (1980) Economic monetary aggregates: an application of index number and aggregation theory. Journal of Econometrics 14:11–48, Reprinted in Barnett and Serletis (2000), Chapter 2, pp. 11–48

Barnett W (1982) The optimal level of monetary aggregation. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 14:687–710, Reprinted in Barnett and Serletis (2000), Chapter 7, pp. 125–149

Barnett W (2012) Getting it wrong: how faulty monetary statistics undermine the fed, the financial system, and the economy. MIT, Cambridge

Barnett W Spindt P (1982) Divisia monetary aggregates: compilation, data, and historical behavior. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Staff Study, 116

Barnett WA, Chauvet M (2011) Financial aggregation and index number theory. World Scientific Books, Hackensack

Barnett W, Serletis A (2000) The theory of monetary aggregation. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Belongia M, Ireland, P (2012) Where simple sum and divisia monetary aggregates part: illustrations and evidence for the United States. University of Mississippi, working paper

Cynamon B, Dutkowsky D, Jones B (2006) Redefining the monetary aggregates: a clean sweep. Eastern Economic Journal 32(4):661–672

Diewert W (1999) Index number approaches to seasonal adjustment. Macroeconomic Dynamics 3:48–68

European Central bank (2000) Seasonal adjustment of monetary aggregates and HICP for the Euro Area. European Central Bank, Frankfurt

Farr HT, Johnson D (1985) “Revisions in the Monetary Services (Divisia) Indexes of Monetary Aggregates.” Staff Study 147, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Federal Reserve Board (2003) Federal reserve statistical release: H.6-monety stock measures. Retrieved from Discontinuance of M3.: www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/20060323

Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2012) Primary dealer statistics XML data. Retrieved from http://www.newyorkfed.org/xml/gsds_finance.html

Federal Reserve Board of Governors (2012) Statistics and Historical Data. Retrieved 2012, from http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/current/default.htm

Hanke S (2011) Malfeasant Central bankers, again. Energy Tribune

Hanke S (2011) The whigs versus the schoolboys. Globe Asia, 20–22

International Monetary Fund (2008) Monetary and financial statistics: compilation guide. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Jones B, Dutkowsky D, Elger T (2005) Sweep programs and optimal monetary aggregation. Journal of Banking & Finances 29:483–508

Offenbacher A, Shachar S (2011) Divisia monetary aggregates for Israel: background note and metadata. Bank of Israel, Research Department: Monetary/Finance Division

Serletis A, Gogas P (2012) Divisia monetary aggregates for moentary policy and business cycle analysis. University of Calgary, working paper

Thornton D, Yue P (1992) An extended series of divisia monetary aggregates. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 74(6):35–52

Thorp J (2003) Change of seasonal adjustment method to X-12 ARIMA. Monetary and Financial Statistics, pp 4–8

TreasuryDirect (2012) Monthly Statement of the Public Debt (MSPD) and Downloadable Files. Retrieved 2012, from http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/mspd.htm

United States Census Bureau (2012) X-12 arima. Retrieved April 2012, from US Census Bureau: http://www.census.gov/srd/www/x12a/

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Richard G. Anderson at the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank for providing much of the needed data. The authors would also like to thank Steve Hanke, David Beckworth, Peter Ireland, and the participants at the 16th Annual International Conference on Macroeconomic Analysis and International Finance in Crete for their valuable input and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Regression Estimates for Broad-Aggregate Component Levels and Rates

Appendix: Regression Estimates for Broad-Aggregate Component Levels and Rates

For the broad-aggregate components not all data were available from a single source survey, or in some cases were not available at all for historical values. These levels and interest rates are estimated to fit with the current resources. In all cases a simple linear regression without a constant was used to approximate the past values. These estimations are used in the case of component levels for large denomination time deposits, levels of commercial paper, and levels and rates of repurchase agreements.

Because of the lack of data or the use of two distinct surveys for repo asset levels and interest rates, the past values of the components are estimated using a growth rate method of back calculation. A simple linear regression estimate was taken as well, but the splice produced large jumps at the point in time the series were linked.Footnote 19 To avoid this jump, the growth rate method is used for the levels of repos instead. For the linear regression estimate, the values of the estimated survey are about 2.97 times those of the original, while the values for the growth rate method are 2.51 times the original levels. NYREPO t is the level of repos from the New York Fed’s Primary Dealer Statistics survey, and RPNS t is the monthly overnight and term RPs for commercial banks, available but discontinued on FRED. As previously mentioned, these two surveys are different, since NYREPO t takes values for all primary dealers (banks, securities), while RPNS t is described in FRED as only surveying commercial bank deals. The monthly growth rates for each series were calculated, DNYREPO t and DRPNS t , where D is the percentage growth rate operator. The growth rates from the FRED series are preserved for the months before October 2001, and then used to back calculate the levels from the initial level of the Primary Dealer Survey. For T, the time of the splice (October 2001), the initial Primary Dealer Survey is used to estimate the last value for repo levels available on FRED:

For all the preceding time periods, 0 ⩽ s ⩽ T − 2, the levels were estimated following the back calculation pattern and the available levels from the FRED survey:

The values for interest rates of repos were not available before 1995, and there was no comparable survey of repo rates from which to estimate. The available repo rates after 1995 were compared graphically to other interest rates, and the T-Bill rate was found to be the closest approximation and most useful, since it is available back to 1967 without any significant splices or changes of survey. Another linear regression without a constant was taken to determine the coefficient for the past values of the I-Repo interest rate index:

where IREPO t is the IREPO Index, β r is the coefficient of the interest rate, and TB3MS t is the 3-month Treasury bill secondary market (monthly) rate from FRED. For the overlapping period from November 1996 to December 2011, β r was estimated, and the past values of the repo interest rate were then determined by:

In addition to estimating repo levels and rates, we spliced the levels for large denomination time deposits and commercial paper to compensate for their collection by two different surveys. The splice again uses a simple linear regression, and estimates the coefficient of the levels between the two surveys without intercept. For commercial paper, both asset level surveys are available from the Federal Reserve Board Statistics website under “Commercial Paper”.Footnote 20 The first survey is the “old structure” survey and runs to March of 2006. The “new structure” survey begins in January 2001. For the simple regression, NSCP t is the new structure commercial paper values, while OSCP t are the old structure commercial paper values. For the overlapping time period, β CP is estimated by \( {\widehat{\beta}_{CP}} \) and used to model the new survey values before January of 1991, as follows:

Large denomination time deposits face a similar two-survey problem, requiring a splice. Again the same simple linear regression method is used to join the two surveys together. The current values come from the H.8 Survey, available from the Federal Reserve Board Statistics website. The previous values are provided by the FRED series, which were discontinued in March of 2006 along with other M3 components. Since the two series are different in their overlapping time periods, estimation was needed for those values before 1973. In 1973, the H.8 survey values are used outright, so the only estimation is for those values from 1967 to the end of 1972. The following equations relateLTDSL t , which is FRED’s seasonally-adjusted monthly level of large time deposits from commercial banks, H8LTD t , which is the value of large time deposits provided by the H.8 Survey, and \( {\widehat{\beta}_{LTD}} \), which is the estimated value of the coefficient, β LTD :

Table 3 is provided as a quick guide to these estimations. The table provides the sources, the overlapping time period used in the regressions, the time periods within which estimations were used, and the estimated values of the coefficients used to derive the past values.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barnett, W.A., Liu, J., Mattson, R.S. et al. The New CFS Divisia Monetary Aggregates: Design, Construction, and Data Sources. Open Econ Rev 24, 101–124 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-012-9257-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-012-9257-1