Abstract

Background

Knowledge of biological and climatic controls in terrestrial nitrogen (N) cycling within and across ecosystems is central to understanding global patterns of key ecosystem processes. The ratios of 15N:14N in plants and soils have been used as indirect indices of N cycling parameters, yet our understanding of controls over N isotope ratios in plants and soils is still developing.

Scope

In this review, we provide background on the main processes that affect plant and soil N isotope ratios. In a similar manner to partitioning the roles of state factors and interactive controls in determining ecosystem traits, we review N isotopes patterns in plants and soils across a number of proximal factors that influence ecosystem properties as well as mechanisms that affect these patterns. Lastly, some remaining questions that would improve our understanding of N isotopes in terrestrial ecosystems are highlighted.

Conclusion

Compared to a decade ago, the global patterns of plant and soil N isotope ratios are more resolved. Additionally, we better understand how plant and soil N isotope ratios are affected by such factors as mycorrhizal fungi, climate, and microbial processing. A comprehensive understanding of the N cycle that ascribes different degrees of isotopic fractionation for each step under different conditions is closer to being realized, but a number of process-level questions still remain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is a key limiting resource in many terrestrial ecosystems and its cycling affects almost all aspects of ecosystem function (Vitousek et al. 1997). The N cycle is complex, with multiple transformations, feedbacks, and interactions with other important biogeochemical elements. N supplies to plants limit primary productivity across a wide variety of ecosystems (LeBauer and Treseder 2008; Thomas et al. 2013). Because N concentrations in plants are also often limiting to herbivores, N supplies to plants can constrain the productivity of herbivores by limiting both the quantity and nutritional quality of plants (Augustine et al. 2003; Craine et al. 2010; Zavala et al. 2013). N supplies can also influence detritus-based food webs, leading to both positive and negative feedbacks on process rates of N cycling. For example, increased N availability can accelerate initial decomposition rates of plant litter, but can also decelerate the decomposition of biochemically recalcitrant organic matter in soils (Carreiro et al. 2000; Craine et al. 2007; Janssens et al. 2010; Melillo et al. 1982; Waldrop et al. 2004). Adding to these complexities, ecosystem N cycling rates can govern N losses. Trace N gas losses to the atmosphere are a strong forcing factor for global climate and increase with increasing soil N availability (Barnard et al. 2005; Hall and Matson 2003). N also plays a key role in limiting productivity in many aquatic ecosystems. Large losses of reactive N, such as NO3 −, from soils can pollute groundwater and streams and ultimately reduce oxygen levels in river and estuarine environments (Howarth et al. 1996; Rabalais et al. 2002).

Understanding how patterns in terrestrial N cycling emerge within and across ecosystems is central to predicting patterns of plant productivity, ecosystem carbon sequestration, nutrient fluxes to aquatic systems, and trace gas losses to the atmosphere (Galloway et al. 2008; Goll et al. 2012; Hudman et al. 2012; Pinder et al. 2012). Many specific N cycling processes can be difficult to measure, constraining the ability to generalize about the N cycle. Consequently, controls on N cycling are uncertain in many cases. No less uncertain is how N cycling responds to forcing factors such as changes in climate, increases in atmospheric CO2, or greater N deposition. Such uncertainty in the mechanisms underlying how N is cycled across organism to landscape scales hampers parameterization of Earth system models and thus our ability to develop prognostic understanding of how ecosystems will respond and feedback to changes in climate (Thomas et al. 2015).

The ratios of 15N:14N in plants and soil have been used to infer N cycling process that are difficult to measure directly and challenging to scale (Amundson et al. 2003; Craine et al. 2009; Handley et al. 1999b; Hobbie and Högberg 2012; Högberg 1997; Martinelli et al. 1999). Although mechanistic understanding of controls over N isotope abundance was already well-developed over 25 years ago (Högberg 1997), during the past decade, a number of advances have been made in quantifying N isotope patterns of plants and soils at local to global scales as well as the mechanisms that underlie these patterns. As N isotopes of plants and soil are relatively straightforward to measure, a better mechanistic understanding of the patterns of natural abundance 15N and their underlying causes is needed to infer spatial and temporal patterns of N cycling as well as their interpretation. The ratios of N isotopes in plants are more likely to reflect short-term variation in N cycling, e.g., annual time scales. Soil N isotopes integrate over longer time scales, e.g., centurial, and can include different processes than what control plant N isotope composition (Bustamante et al. 2004). N isotopes are also a key to reconstructing past N availability, which helps us understand the current state and trajectory of N availability of ecosystems (Gerhart and McLauchlan 2014; McLauchlan et al. 2013).

This review has three main sections. First, we provide background on the main processes that affect plant and soil N isotope ratios. Second, we review the mechanisms that affect plant and soil N isotope patterns and the general ecological patterns of N isotopes in plants. Lastly, we identify some of the remaining questions that need to be answered in order to advance our understanding of N isotopes in terrestrial ecosystems and consequently the N cycle.

Background on the N cycle and N isotopes

The soil N pool accounts for less than 1% of global N reservoirs and plant N pools account for even less (Galloway et al. 2004). Both are essential for the functioning of ecosystems and the biosphere. N cycling rates and the predominant forms of bio-available N to plants varies among ecosystems. In cold ecosystems, dissolved organic N (DON) can be a dominant pool of N in soil solution (Schimel and Bennett 2004). In warmer ecosystems, either NH4 + or NO3 − may dominate the inorganic N pool of an ecosystem (Kronzucker et al. 1997). Although plants benefit energetically from taking up the most reduced form of N, excessive uptake of NH4 + can be toxic (Miller and Cramer 2005) and plant N uptake preferences track the availability of different forms of N across different environmental conditions (Wang and Macko 2011). Losses of bioavailable N can be indicative of the N limitation status of plants and microbes and tend to increase with increasing external inputs and availability (e.g., Brookshire et al. 2012a; Vitousek et al. 1989; Wang et al. 2007). Pathways of N loss from ecosystems are diverse. They include gaseous losses (e.g., denitrification), particulate losses through erosion (aeolian or hydrologic pathways), and leaching of organic and inorganic N.

Although the N cycle is composed of many processes that can be difficult to measure, the ratios of 15N:14N in plants or soils could shed light on patterns of key aspects of the N cycle. These aspects include N supply rates to ecosystems and plants, the availability of N to plants, the pathways by which N is lost from ecosystems, and the amounts of N lost. For the purposes of this review, we define ecosystem N supply as the total amount of N entering the ecosystem from the atmosphere by pathways such as biological fixation and deposition, and from bedrock weathering in some situations. Soil N supply is defined as the rates at which organic or inorganic N enters soil solution from organic matter decomposition and from different direct inputs to the ecosystem. Soil N supplies to plants can be measured as either net mineralization rates or a fraction of gross mineralization rates, but it is uncertain which of these better predict plant N uptake. In most ecosystems, inorganic N (NH4 + and NO3 −) is the major N form for plant uptake, though some plants (directly and through mycorrhizal fungi) can take up DON, which precedes mineralization (Näsholm et al. 1998). The availability of N in soils to plants can be defined as the soil N supply relative to plant demand for N. Because the availability of N represents the balance of supply and demand, N availability can be even harder to measure directly than supply rates alone since plant N demand must also be assessed. Lastly, it is important to quantify the pathways by which N is lost from the ecosystem. For some purposes, the absolute magnitude is sufficient, while in others the relative loss rates among pathways or relative to mineralization may be preferred.

As a natural component of the total N pool, approximately ~0.366 % of N is in the form of 15N. The ratio of 15N to 14N present in a given pool can shed light on processes that are difficult to measure. Molecules containing 15N are discriminated against in a number of processes associated with equilibrium and kinetic fractionations. N stable isotopic compositions are typically reported in δ notation, and expressed in per mil (‰) (Coplen 2011):

where (15N/14N)sample is the N isotopic composition of a sample, and (15N/14N)std is the N isotopic composition of the standard material. The material used as a standard for the ratio of stable N isotopes is atmospheric molecular N, which by convention is set to 0 ‰. The fractionation between two substances A and B, which applies to all mass fractionation such as thermodynamic isotope effect and diffusion fractionations, can be expressed using the isotope fractionation factor (α):

where R = the ratio of the heavy isotope to the lighter isotope in compounds A and B. Fractionation factors can also be expressed as discrimination (Δ), or fractionation (ε; also referred to as the “isotope effect”), which is also normally expressed in ‰. These are defined (Coplen 2011) as

The approximation in Eq. (3) is valid when α is low or under natural abundance. In general, patterns of natural abundance 15N have proven difficult to explain with simple mixing models. A key reason for this is that many biochemical and abiotic reactions involving N have large fractionation factors, which may vary in their level of expression depending on the degree to which the reactions go to completion. There are few N sources that are sufficiently enriched or depleted relative to other pools of N in an ecosystem to serve as a distinct tracer (Robinson 2001). Using natural abundance δ15N of plants or soils to infer N cycling processes is thus difficult because there is a single response variable with multiple drivers. Interpretations, however, can be refined by having multiple-responses, such as pairing N with O isotopes when studying NO3 − (Högberg 1997) or with C isotopes when studying organic biomolecules (Baisden et al. 2002a). Yet, in most cases, natural abundance N isotopes can only be used to narrow down the mechanisms that might underlie plant or soil δ15N patterns. Coupling measurements of δ15N with direct measurements of N cycle processes is generally required to further narrow interpretations of patterns.

Plant N isotopes

Although N in plant biomass represents a small fraction of the total ecosystem N pool, the isotopic composition of plants can index short-term dynamics of N cycling, as opposed to soil δ15N which might represent long-term dynamics. Typically, plant leaves are used as an index of whole-plant δ15N. Although differences often exist among leaves, roots, and stems (Kolb and Evans 2002), the N isotope ratios generally correlate among plant fractions and any average differences are generally relatively minor. For example, across 90 grass species collected from 67 sites in four grassland regions of the world, the δ15N of leaves averaged just 0.3 ‰ less than those of roots compared to a range of 18 ‰ for leaves and 14 ‰ for roots (Craine et al. 2005). Similarly, Dijkstra et al. (2003) reported differences in δ15N of <1 ‰ between leaves and roots of natural meadows and forests in North America, with direction and magnitude of the differences depending on the functional type (forbs, legumes or grasses). In two North American hardwood tree species, δ15N of leaves and wood were within 0.3 ‰ on average (Pardo et al. 2012). In that study, the greatest average difference in δ15N occurred between roots and leaves for sugar maple (Acer saccharum) (2.1 ‰). Offsets between leaves and roots appear to be greatest for plants with ectomycorrhizal symbioses, e.g., ~4 ‰ enrichment in roots relative to leaves. That offset is dependent on the mycorrhizal status of the plants and on how much ectomycorrhizal mass is included with the roots (Hobbie and Colpaert 2003). In agricultural crops supplied with N-fertilizers, differences between leaves and roots can be larger (Robinson et al. 1998). For example, leaves of Brassica campestris grown with 12 mM NO3 − had leaf and root δ15N values of 0.2 ‰ and −6.7 ‰, respectively (Yoneyama et al. 2003).

At the global scale, foliar δ15N ranges over 35 ‰ (Craine et al. 2009, 2012). The highest foliar δ15N from a natural environment was 21.4 ‰, acquired from a prairie wildflower (Callirhoe involucrata) adjacent to a bison wallow in a tallgrass prairie in Kansas, USA (Craine et al. 2012). The lowest foliar δ15N recorded was −14.4 ‰, acquired from a fir tree (Abies lasiocarpa) near Lyman Glacier in Washington, USA (Hobbie et al. 2005). Across over 12,000 leaves collected globally (Craine et al. 2009, 2012), the mean δ15N was 0.9 ‰ with 95% of the samples falling within a range of 15.5 ‰ (−7.8 ‰ to 8.7 ‰)

Locally, individual plants can vary in δ15N by over 25 ‰ (Craine et al. 2012). The amount of variation in plant δ15N observed at a particular site depends in part on the sampling intensity. Using data from Craine et al. (2012), the range of foliar δ15N observed at a site increases logarithmically with the number of plants sampled, which includes additional species and replicates of the same species. When 10 plants are sampled at a site, the mean range averages 5.5 ‰. When 100 plants are sampled, the mean range averages 10.1 ‰. (Fig. 1). In contrast to other studies (Nadelhoffer et al. 1996), ecosystems with low mean annual temperature do not necessarily show a greater range in foliar δ15N than ecosystems with high mean annual temperature. There is no relationship between mean annual temperature or precipitation and the range of foliar δ15N at a site, once the number of plants sampled is taken into account (P > 0.2).

Proximal causes of plant δ15N variability

The variation observed within and among sites in foliar δ15N is dependent on a large number of proximal factors. In the following sections, we discuss a number of these factors: the signature of deposited N, whether any N has been acquired from geologic sources, the amount of N acquired from symbiotic fixation by the plant, the form of N acquired, mycorrhizal symbioses, and the signature of the N lost from ecosystems. Questions about the role of variation in the signature of soil organic matter (SOM) in determining plant δ15N are addressed in a later section.

Deposition

Deposition of N can alter plant δ15N when plants directly acquire N on leaf surfaces or by altering the signature of available N in the soil. NO3 − in bulk precipitation tends to have an isotopic signature ranging from −3 to + 1 ‰ (Houlton and Bai 2009), likely reflecting anthropogenic NOx originated from fossil fuel combustion and reduction (Felix et al. 2012). For systems receiving substantial amounts of rain from marine sources, the contribution of continental anthropogenic N sources can be traced using the dual (15N, 18O) isotopes of NO3 −. For example, rain in Bermuda can be derived from cold-season continental USA sources (with NO3 − that have low δ15N and high δ18O likely reflecting the contribution of fossil fuels) or warm-season marine sources (with high δ15N and low δ18O derived from natural atmospheric reactions). Consequently, the source of NO3 − varies temporally resulting in a negative relationship between δ18O and δ15N with the lowest δ15N and highest δ18O derived from the continental USA (Altieri et al. 2013). In contrast, NO3 − deposited onto ecosystems can have quite low δ15N when it is generated from snow surfaces. Morin et al. (2009) showed that the photolysis of NO3 − on snow surfaces can lead to deposition of highly 15N-depleted NOx downwind (as low as −40 ‰).

NH4 + in bulk precipitation not derived from marine sources tends to have lower δ15N values than NO3 − (Garten 1992; Koba et al. 2012; Xiao and Liu 2004; Zhang et al. 2008), possibly reflecting the agricultural sources of NH4 +. The isotopic signature of atmospheric NH4 + is likely affected by marine sources. For example, a wide range in δ15N values of NH4 + in the bulk precipitation was collected near a bay in the eastern US (−8.3 to + 8.6 ‰) likely due to differences in whether NH4 + was derived from terrestrial or marine sources (Russell et al. 1998). However, the ranges of δ15N for NH4 + and NO3 − occasionally overlap (Russell et al. 1998) or NH4 + can have higher δ15N than NO3 − (Nadelhoffer et al. 1999).

For DON in precipitation, there are a limited number of measurements of its isotopic values. Cornell et al. (1995) first reported δ15N of DON in precipitation on the ocean. DON values ranged from −7.3 to +7.3 ‰, with a trend towards 15N-depletion in sites further from the ocean. Russell et al. (1998) also reported a wide range in δ15N of DON (−0.5 to +14.7 ‰). Knapp et al. (2010) estimated δ15N of total reduced N (DON + NH4 +) in precipitation collected in Bermuda to be −0.6 ‰ compared to δ15N of NO3 − of −4.5 ‰ in the same samples.

The isotopic signatures of different compounds differ between wet and dry deposition (Heaton et al. 1997). For instance, Elliott et al. (2009) measured δ15N of HNO3 (gas; mean value = −3.2 ‰) and NO3 − (particulate; +6.8 ‰). They found that δ15N values of HNO3 (gas) are an average of 3.4 ‰ higher than corresponding δ15N of NO3 − in wet deposition. For NO3 −, a trend in higher δ15N values in dry deposition than wet deposition has been reported elsewhere (Garten 1996), although one study (Mara et al. 2009) reported similar δ15N values for NO3 − in dry and wet depositions in a coastal region. Kawashima and Kurahashi (2011) reported quite high δ15N of particulate NH4 + in some rural sites in Japan, which had much higher values than δ15N of particulate NO3 − (16.1‰ vs. -1‰). In contrast, δ15N was higher in NO3 − than in NH4 + on aerosol samples collected in a coastal sampling site (Yeatman et al. 2001).

Geologic N

Rocks contain approximately 99.9% of the fixed N on Earth (Capone et al. 2006). Such “geologic N” represents the accumulated products of physical and biological N2 fixation after gaseous N losses and losses from weathering and erosion. The geological N pool is large and turns over at the scale of millions of years as high pressures and temperatures volatilize N in rock. Past work has indicated that N concentrations are greatest in sedimentary and low-grade meta-sedimentary rocks such as slate (~500 ppm on average) (Holloway and Dahlgren 2002), whereas high-grade metamorphic rocks such as gneiss and igneous rocks contain smaller quantities of fixed N. Rock-bound N can occur as organic N, NH4 +, and, to a lesser extent in desert caliche deposits, as NO3 −.

Substantial rock N contributions to sediments, ground- and surface-waters, and soil-systems are well known (Dahlgren 1994; Holloway et al. 1998; Holloway and Dahlgren 2002; Strathouse et al. 1980). Weathering of parent material contributes significant quantities of N to temperate coniferous forest ecosystems (Morford et al. 2011). Using natural N isotope composition, Morford et al. (2011) showed that the δ15N of rock N was distinct from other N input sources in California, e.g., approximately 16‰ higher than symbiotically fixed N. Application of an N-isotope mixing model revealed a doubling of the forest N budget via weathering of geologic N. The potential for N isotope composition to reveal rock N sources in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems is an area for open inquiry; however, current evidence indicates that rock mineral δ15N is highly variable (from ~ −11 to 24 ‰) (Holloway and Dahlgren 2002), making global-scale N isotope calculations of rock N inputs uncertain (Vitousek et al. 2013).

N2 Fixation

There is virtually no variation in the δ15N of N2 in the global bulk atmosphere (Mariotti 1983) and only slight 15N depletion in the soil atmosphere (ca. -0.2 ‰) imposed by diffusive flux of water vapor out of soil combined with gravitational settling of heavier isotopes and thermal diffusion of heavier isotopes to sites with lower temperatures (Severinghaus et al. 1996). The concentration of N2 in the soil atmosphere is high enough that N2 production by denitrification and diazotrophic N2 consumption have limited potential to influence the δ15N of soil N2 (Barford et al. 1999).

During enzymatic fixation of N2, the substrate N2 binds reversibly to nitrogenase, facilitating potential discrimination against 15N (Sra et al. 2004). The NH3 produced is highly soluble and rapidly converts to NH4 + with the equilibrium in favor of 15N-enriched NH4 + formation (Shearer and Kohl 1986). It is widely accepted, however, that nitrogenase in nature does not fractionate (Handley 2002). Although free-living diazotrophs fractionate slightly (~ −2.5 ‰), there is little fractionation by symbiotic fixation in legumes. Yet, nitrogenase in vitro has been reported to fractionate strongly (−17 ‰) (Sra et al. 2004). This raises the question as to how inherent fractionation by nitrogenase may be suppressed, particularly in symbiotic fixation (Handley 2002). Contrary to earlier perspectives (Handley and Raven 1992), Unkovich (2013) suggested that these differences in fractionation were due to reduced N2 concentrations in nodules as a consequence of the O2 barriers that also exclude N2. Steps subsequent to the N2 reduction may also contribute to compensating for nitrogenase fractionation, including gaseous N loss (e.g., as NH3), export of 15N-depleted ureides and the import of 15N enriched amino acids (Unkovich 2013).

The δ15N values of plants that rely exclusively on N2 fixation are usually ~ 0 ‰, reflecting atmospheric isotopic N values (Handley 2002). Many N2-fixing plants show significant departures from 0 ‰ due to differences in reliance on fixed N (Craine et al. 2009; Menge et al. 2009). Unkovich (2013) argued that variations in δ15N of symbiotic N2 fixation were not the product of N2-fixation per se, but rather a combination of measurement errors, intra-plant fractionation events resulting in tissue differences and possible preferential losses of 15N-depleted NH3 (O’Deen 1989).

Nodules are commonly highly enriched in 15N (e.g., δ15N 2.5–6.3 ‰) (Shearer and Kohl 1986). A number of explanations for this enrichment have been provided, including losses of 15N-depleted NH3, export of 15N-depleted ureides and the import of 15N-enriched amino acids (Unkovich 2013). Nodules generally form a small proportion of the biomass of legumes and also represent a small proportion of the plant N (<10%) even in plants exclusively dependent on N2 fixation. As a consequence, enrichment of nodules has little effect on overall plant δ15N values.

Transformations of plant-available nitrogen in soil

Feigin et al. (1974) first illustrated that the δ15N of different types of soil inorganic N can be altered by transformations such as mineralization and nitrification. Although the subsequent number of studies on δ15N of soil inorganic N remains small compared with the studies on bulk soils, many have revealed reduced δ15N values for soil inorganic N (NO3 − plus NH4 +) than bulk soils in most cases (Binkley et al. 1985; Garten 1992; Koba et al. 1998).

The lower δ15N of soil inorganic N relative to bulk soil N has been attributed to the isotopic fractionation during mineralization of larger molecules in the soil, although there is very little evidence for fractionation during this step (Högberg 1997). Consistent with previous research, Koba et al. (2010) demonstrated that soil inorganic N produced by organic matter mineralization and nitrification had more negative δ15N values than bulk soil. Yet, the authors also reported that extractable organic N (EON) fraction had the highest δ15N values among different N pools in the soil (Fig. 2). This finding is somewhat unexpected; investigators typically assume that DON—comparable with EON in this case—has the same δ15N of bulk soil N, because solubilization of organic N from bulk soil into the soil solution does not appear to induce isotopic fractionation (Amundson et al. 2003). This finding cannot be interpreted with the conventional view of N mineralization with negligible or small isotopic fractionation between SOM and EON. Koba et al. (2010) reported that the difference between the δ15N of bulk soil N and EON was positively correlated with bulk soil C:N.

Relationship between bulk soil δ15N and the δ15N of organic N (closed squares), NH4 + (closed circles), and NO3 − (open circles) across a range of soil depths from a subtropical forest in China (Koba et al. 2010). Each point represents a value derived from a particular soil depth (O horizon-100 cm) from three different locations within the forest

Soil microbial functioning is a likely driver of differences between δ15N of bulk SOM and EON. Macko and Estep (1984) demonstrated 15N-enrichment of a marine bacterium after their uptake of amino acids. An analysis of ten different soils from a range of ecosystem and climate types showed that soil microbial biomass was consistently 15N-enriched relative to the total N pool (by approximately 3.2 ‰) and the extractable N pool (~3.7 ‰) (Dijkstra et al. 2006). Along these lines, soil microbial biomass can be 15N-enriched compared with the substrate due to the excretion of 15N-depleted N compounds (e.g., NH3) (Collins et al. 2008). Dijkstra et al. (2008) hypothesized that soil microbial biomass would excrete N with low δ15N during deamination and associated transaminations of the incorporated organic N when C availability is low, resulting in the increase in δ15N compared with the δ15N of substrate. Expanding on these ideas, Coyle et al. (2009) suggested that greater 15N-enrichment of the soil microbial biomass in lower C:N soils may result from relatively lower C availability, a feature realized in some grassland soils (Tiemann and Billings 2011).

The 15N-enrichment in soil microbial biomass illuminates two points. The first is the discrepancy between the 15N-depletion of soil inorganic N and the lack of reports of large isotopic fractionation during mineralization. Mineralization does not break –NH2 bonds at the edges of organic matter molecules in the soil. Instead, mineralization is the consequence of incorporation and excretion of N by soil microbial biomass (Myrold and Bottomley 2008). Therefore, it is reasonable that soil inorganic N excreted from soil microbial biomass can be 15N-depleted. Second, δ15N of EON tends to be relatively elevated. The growing recognition that microbial necromass dominates inputs into SOM pools with longer turnover times (Berg and McClaugherty 2008; Gleixner 2013; Hobara et al. 2013; Liang and Balser 2010) is supported by the high δ15N of these pools in the soil.

Nitrogen uptake

The isotopic fractionation that occurs during the uptake of soil N into plant tissue varies among plants and depends on the concentrations of N at the root surface. If the concentration of N in soil solution is extremely low, roots essentially eliminate the possibility of N-isotope fractionation since net flow of N is from soils to roots. Concentrations of the N at root surfaces are difficult to measure but minimum soil solution N concentrations required for uptake of NO3 − are extremely low (~0.3–9 μM) (Edwards and Barber 1976; Olsen 1950; Teo et al. 1992), and those for NH4 + are in the same range (~1.5–5 μM) (Abbes et al. 1995; Marschner et al. 1991). Soil amino acid concentrations are also commonly low, relative to [NO3 −] and [NH4 +], resulting in limited access of plant roots to these N-forms (Jones et al., 2005) and limited potential for fractionation. Nutrient uptake mechanisms allow roots to take up N at low concentrations and consequently deplete soil N to low concentrations (Miller and Cramer 2005), which is consistent with the fact that observed fractionation is especially small when soil [N] are low (Evans 2001; Evans et al. 1996; McKee et al. 2002; Montoya and McCarthy 1995). It is only when soil [N] is high that significant fractionation may be common.

Discrimination against 15N during uptake of NO3 − by 38 plant species altered plant δ15N by only 0.25 ‰ on average, although the extent of fractionation increased with increasing NO3 − concentration (Mariotti et al. 1980). Evans (2001) used the fact that discrimination between NO3 − and tissue can be ~0 ‰ across a range of NO3 − concentrations to argue that there is no inherent fractionation during NO3 − uptake processes. Furthermore, in aquatic systems, the cellular NO3 − of phytoplankton has never been observed to be depleted in 15N relative to the supply (Needoba et al. 2004) indicating that fractionation during uptake across cell membranes is unlikely. Fractionation with NH4 + may, however, be greater than with NO3 − supply (Pennock et al. 1996; Yoneyama et al. 1991). Possible steps during NH4 + acquisition from soil that could result in isotopic fractionation are NH4 + diffusion across the root boundary layer, active transport of NH4 + across the plasmalemma and assimilation into amino acids. Fractionation during uptake has been reported to result in increased δ15N values of tissue NH4 + and decreased δ15N values of organic N in rice (Yoneyama et al. 1991). This observation is consistent with fractionation during NH4 + assimilation into organic N.

The foregoing suggests that evidence for extensive fractionation of N during influx into cells, per se, is rather weak. Despite this, cytoplasmic pools of both NO3 − and NH4 + are commonly enriched with 15N, largely due to fractionation during reduction of NO3 − to NO2 − by nitrate reductase, the reduction of NO2 − to NH4 + by nitrite reductase, and the subsequent assimilation into amino acids glutamine synthetase–glutamate synthase (Needoba et al. 2004). Nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase both fractionate strongly against 15N by ca. 15‰ and 17‰, respectively (Robinson 2001). In contrast, the reduction of NO2 − to NH4 + is unlikely to fractionate in situ since cellular [NO2 −] is normally very low (Tcherkez 2011). Cumulatively, these fractionations cause the cytoplasmic inorganic N to become enriched in 15N compared with soil N, whereas the organic N product is depleted in 15N. The importance of these fractionations for plant δ15N values varies with the locations of N reduction/assimilation, which can be leaves, roots, or both, depending on the species, environmental conditions and N source (Robinson et al. 1998). When reduction/assimilation occurs in the roots there is potential for the efflux of 15N-enriched inorganic N from roots, resulting in both depletion of plant-15N and enrichment of soil 15N. Efflux of NO3 − is commonly observed (Kronzucker et al. 1999) and a Nitrate Excretion Transporter (NAXT1) has been associated with NO3 − efflux in Arabidopsis (Segonzac et al. 2007). Efflux of NH4 + has also been widely reported (Britto et al. 2001). Both NO3 − and NH4 + efflux are thought to function for regulation of cytoplasmic N concentrations. This might be especially important for NH4 + (Britto and Kronzucker 2002), which can be toxic when supplied at high concentrations (Miller and Cramer 2005). Apart from efflux of inorganic N, root exudation of amino acids also occurs (Farrar et al. 2003), resulting in the loss of 15N-depleted organic N from the roots. Dissolved organic N losses are likely to be greatest when substrate [N] is high or when plant growth is relatively impaired.

Other factors that may also contribute to variations in plant tissue δ15N are intra-plant fractionation between shoot and root combined with whether there is net influx or efflux of NH3 from the shoot (O’Deen 1989). Although net efflux of NH3 by tissue volatilization can increase tissue δ15N due to the large isotope fractionation (Högberg 1997), when atmospheric concentrations of NH3 are above a compensation point within leaves, net influx of 15N-depleted atmospheric NH3 can also decrease tissue δ15N (Johnson and Berry 2013).

If the major N source for plants in soils is inorganic N, the δ15N of plants should more closely correlate with the δ15N of that source than total N (Cheng et al. 2010; Virginia and Delwiche 1982). Although a more comprehensive survey and broader sampling are required, published values of foliar δ15N largely reflect the signatures of inorganic N available in soil (Fig. 3). The vicinity of most plots to the identity line indicates that, in most non-boreal sites, plants mainly acquire NH4 + and NO3 − from soil and this uptake occurs without any large isotopic fractionation.

Relationship between δ15N of soil inorganic nitrogen and foliage δ15N. Data derived from multiple sources (Boddey et al. 2000; Cheng et al. 2010; Garten and Van Miegroet 1994; Pate et al. 1993; Takebayashi et al. 2010). When δ15N of soil inorganic nitrogen was not provided in the reference, it was calculated as the mean value of δ15N-NH4 + and δ15N-NO3 −, weighed by the size of these two N pools. Shown are the orthogonal fit (solid line; y = 1.35 + 1.05x; 95% CI for slope = 0.69–1.62, r = 0.74, P < 0.001). Identity line is shown dashed

Mycorrhizal influence on plant δ15N

Mycorrhizal symbioses are ubiquitous features of nearly all plant communities and many plants rely on mycorrhizal fungi to supply them with N (Smith and Read 2008). Mycorrhizal hyphae are narrower in diameter than roots and hence are more efficient in exploring soil for nutrients. Some mycorrhizal fungi are capable of producing enzymes to access organic forms of N. As a result of supplying a significant amount of N to plants and the known fractionation that occurs during N transfers to host plants, some of these fungi can greatly influence the N isotopic patterns in plants and other ecosystem pools (Hobbie and Högberg 2012).

Mycorrhizal fungi can be separated into three major types, arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM), ectomycorrhizal (EM), and ericoid fungi (Hobbie and Hobbie 2008). These fungal types differ considerably in the distance from the root that they can explore (Coleman et al. 2004) and enzymatic capabilities to access different forms of N (Read and Perez-Moreno 2003). These differences can influence foliar δ15N of host plants. At the global scale, Craine et al. (2009) showed that the type of mycorrhizal fungi associated with plants can account for roughly one third of the variation in foliar δ15N values of the more than 9,000 plants sampled. Moreover, the type of mycorrhizal association can significantly influence foliar δ15N values, with ericoid and EM plants being more depleted in foliar δ15N (3.2 ‰ and 5.9 ‰, respectively) than non-mycorrhizal plants. AM plants are intermediate in their isotopic values, being depleted on average by 2 ‰ relative to non-mycorrhizal plants.

The greater difference in foliar δ15N between EM and ericoid plants and non-mycorrhizal plants arises because of the preferential retention of the 15N by fungal biomass and the preferential transfer of 14N to host plants (Hobbie and Colpaert 2003; Hobbie et al. 2000; Hogberg et al. 1996; Taylor et al. 2003). Although AM plants are slightly depleted in 15N relative to non-mycorrhizal plants, there is no clear indication that AM fungi retain a 15N-enriched pool or transfer 15N-depleted N to host plants (Azcon-G-Aguilar et al. 1998; Wheeler et al. 2000). However, it is difficult to quantify N retention by AM fungi and thus it is uncertain to what degree AM fungi contribute to variation in foliar δ15N (Handley et al. 1999b). Some of the differences in foliar δ15N between AM and non-mycorrhizal plants might be due to differences in the form of N directly acquired by the plants or the environments they tend to occupy.

Plant N isotopes have also been used to determine the role mycorrhizal fungi play in host plant N acquisition. Using a mass-balance approach based on the natural abundance values of 15N in plant foliage, EM sporocarps, and soil, Hobbie and Hobbie (2006) devised an analytical model to quantify the amount of N transferred from EM fungi to host plants in N-limited environments. Their model showed that 61-86% of the N in arctic plants was supplied by mycorrhizal fungi. However, it is important to point out that estimates of the proportion of N in the host plant derived from mycorrhizal fungi are sensitive to the 15N values of N sources. Hobbie and Hobbie (2006) used the δ15N signature of bulk soil N as their N source. A later study divided the bulk soil N into inorganic and organic fractions that differ in their isotopic values. Hydrolysable amino acids were as much as 10 ‰ less than other fractions in bulk soil (Yano et al. 2010). Using the signature of the labile N instead of bulk soil, Yano et al. estimated that only 30-60% of the plant’s N was supplied by mycorrhizal plants. It is therefore crucial to determine the δ15N signature of available N sources to accurately understand the role EM fungi play in host plant N acquisition.

Ecosystem N losses

In ecosystems where the isotopic signature of N inputs does not differ significantly from that of the atmosphere, loss pathways are the primary factors that ultimately enrich ecosystem N, but they also influence the signature of N available to plants. Comprehensive synthesis of isotope systematics in gaseous and hydrologic (particulate and dissolved) N losses from ecosystems has been limited primarily by the inability to measure natural abundance losses of N2 from denitrification against the large background of atmospheric N2 (Houlton and Bai 2009). Gaseous losses are expected to have large fractionation factors, but the observable expression of isotope effects depends strongly on the degree to which the reaction goes to completion (Bai and Houlton 2009; Craine et al. 2009).

Hydrologic losses (leaching and erosion) do not seem to be accompanied by fractionation, as the exported nitrate, DON and particulate N have similar δ15N of ecosystem N. Therefore, gaseous losses appear primarily responsible for imprinting large scale patterns on the natural abundance δ15N of plants and ecosystems (Houlton and Bai 2009). Systematic understanding of isotope effects associated with soil N loss pathways can best be organized by following the dominant soil N transformations from the mineralization of SOM into each loss pathway. The mineralization process itself will introduce variability into the δ15N of NH4 + primarily reflecting the δ15N of definable SOM pools or fractions, which varies with factors such as depth.

Once NH4 + has been produced in soil solution, it is subject to volatilization as NH3 under alkaline conditions, which is most likely to occur in hotspots or hot moments. Significant NH3 volatilization can follow animal excreta deposition or fertilizer application. The rate limiting process, diffusion into the atmosphere, has a high fractionation factor (17.9 ‰) that can be calculated in the same manner as for other gases emitted from soil (Stern et al. 1999). Empirical measurements of δ15N for NH3 relative to residual soil or plant NH4 + have indicated 15N depletion by up to 40 ‰ (Högberg 1997), but may also incorporate 15N enrichment of the NH4 + pool due to co-occurring nitrification or a second diffusional fractionation during collection. Under typical situations with high rates of volatilization, not all of the NH4 + pool is lost, so strong expression of the fractionation is expected. Given the large size of ammonia volatilization losses in some ecosystems (Billen et al. 2013), further systematic studies would be beneficial.

Other gaseous losses, including NOx, N2O, and N2, occur mainly during nitrification and denitrification. The well-known loss pathways correspond to a ‘hole-in-the-pipe’ model (Firestone and Davidson 1989), and are also often associated with hot spots and hot moments, suggesting that the reactions responsible for gaseous losses seldom consume the entire reactant pool. Significant 15N enrichment of residual soil N pools can therefore be expected whenever processes that fractionate strongly against 15N are the rate-limiting steps in gaseous loss pathways.

Few N isotope measurements of NOx, N2O, and N2 are available at plot or ecosystem levels, so the potential for isotope effects is commonly assessed through biochemical fractionation factors (Högberg 1997; Mariotti et al. 1982). Reported soil and soil-emitted N2O δ15N values typically range between 0 and −40 ‰ (Pérez et al. 2000, 2001; Pörtl et al. 2007; Van Groenigen et al. 2005; Xiong et al. 2009), and therefore suggest varying but often strong 15N depletion in the gaseous loss pathway. The δ15N values of denitrified N2 emitted from soil to the atmosphere have not been successfully measured. Processes are likely to follow those in groundwater systems, which are closed to atmospheric N2. Under these conditions, a batch reaction model implies that 15N-depletion can be expected as denitrification proceeds, and measurements are believed to demonstrate that the δ15N in excess N2 matches the δ15N of the NO3 − source after nearly complete denitrification (Böhlke and Denver 1995; Böhlke et al. 2002). Gaseous loss pathways including NOx and the HONO pathway (Oswald et al. 2013) also appear likely to have significant biochemical fractionations.

The δ15N signature of NO3 − has been critical to interpreting patterns of denitrification in oceans (Sigman et al. 2000, 2009) as well as terrestrial ecosystems (Bai and Houlton 2009; Brookshire et al. 2012b; Fang et al. 2015; Houlton et al. 2006; Houlton and Bai 2009). Both nitrification and denitrification fractionate 15N strongly with similar fully-expressed organism-level isotope effects of 20–30 ‰ (Högberg 1997; Mariotti et al. 1982). This isotope effect decreases with increasing external NO3 − concentrations and C quality, which affects NO3 − uptake rate, likely resulting in a system-level isotope effect of just 10–15 ‰ (Kritee et al. 2012). A similarly low expression of an isotope effect has also been shown for natural soils (Houlton et al. 2006). Such ecosystem-level underexpression can result from heterogeneity in rate-limiting conditions in the soil environment. Houlton et al. (2006) found that at the wet sites in a Hawaiian forest rainfall gradient, saturating conditions likely drive denitrification to near-completion thus resulting in no net expression of fractionation, a pattern expected from closed-system microsite conditions (Mariotti et al. 1982; Sigman et al. 2001). Plants in these ecosystems are not strongly 15N-enriched, despite high rates of denitrification.

Inorganic N lost from the ecosystem through leaching is either derived from the decomposition of organic matter or direct losses of depositional N. Although the δ15N of NO3 − may not be diagnostic of depositional N, the 18O of NO3 − differs globally by an average of 40 ‰ (range = 20–60 ‰) between atmospheric and biospheric waters. As such, the dual natural abundance isotope distributions of NO3 − (δ15N and δ18O) have been used to partition NO3 − in groundwater or streams into NO3 − that derives from internal microbial nitrification and NO3 − that passes directly from atmospheric sources (Durka et al. 1994). Most studies have found a uniformly low direct contribution of atmospheric NO3 −. However, studies in some temperate regions exposed to chronic atmospheric N pollution show periods of NO3 − loss, particularly during high flow and snow-melt, when up to 20% of NO3 − derives directly from atmospheric sources. Brookshire et al. (2012b) showed that many tropical forests naturally export high levels of NO3 − similar to that of polluted temperate forests but that an average of >98% of the NO3 − derives from nitrification in the plant-soil system. An even more direct way to way to separate atmospheric from microbial effects on NO3 − is through analysis of Δ17O owing to the fact that 17O is enriched in atmospheric NO3 − due to mass-independent photochemical reactions while mass-dependent processes (e.g., nitrification and denitrification) do not affect Δ17O (Fang et al. 2015; Michalski et al. 2004).

Interpreting patterns of plant δ15N within and among ecosystems

Inferring sources of N to plants from plant δ15N

Variation in δ15N among plants within an ecosystem has been interpreted as representing differences in fixation, mycorrhizal dependence, depth of acquisition within the soil profile, utilization of depositional N and the form of N that plants predominantly acquire (Vallano and Sparks 2013). Among ecosystems, variation in plant δ15N can be affected by these same factors, but the form of N is unlikely to drive variation in stand-level signatures when the majority of available N is acquired by plants. For example, if all of the NH4 + and NO3 − available to plants is acquired, differences in signatures between the two caused by fractionation during nitrification will not affect the mean signature of the inorganic N. Among ecosystems, soil and plant δ15N can also be affected by variation in the 15N value of atmospheric N deposition. When distal sources of N have similar values, as described earlier, plants or soils with higher δ15N are often assumed to experience (or have) higher N availability.

As a result of the multiple potential influences on plant or soil δ15N, interpretations are not necessarily straightforward. Given the wide variation in signatures of atmospheric sources of N to plants and multiple factors in the soil that can affect plant δ15N, variation in plant δ15N across spatial gradients or over time cannot only be interpreted as a signal of depositional N. Vallano and Sparks (2013) examined the foliar δ15N of mature trees of four species along an urban–rural gradient that included variation in NO2 concentrations in the atmosphere. They found that after accounting for variation in soil δ15N, there was no relationship between NO2 concentrations and foliar δ15N for two species, a positive relationship for one, and a negative relationship for the fourth. The authors hypothesized that one species utilized enriched N in the atmosphere and the other depleted N. Yet, the signatures of N the plants were differentially accessing would have to differ by 20‰ to generate observed differences in δ15N between the two species (Vallano and Sparks 2008). Even bryophytes that presumably rely on atmospheric N entirely (Binkley and Graham 1981) can vary by 8 ‰ within a narrow geographic region (Delgado et al. 2013).

Interpreting variation among species within a site is complicated due to the multiple processes influencing isotopic values. Although nitrification is a fractionating process, the assumption that variation among plants within a site reflects differences in uptake of NO3 − vs. NH4 + might not be valid (Kahmen et al. 2008). Across a number of European grasslands, species that preferred NO3 − relative to NH4 + under controlled conditions would be predicted to have lower foliar δ15N than plants that preferred NH4 +. Yet, plants that preferred NO3 − were more enriched in 15N, not less enriched. Among potential explanations for this pattern, NO3 − may have been more enriched than NH4 + in the soils due to gaseous N loss subsequent to nitrification. Other differences among plants within a site could be due to differences in dependence on mycorrhizal fungi, or the depth in the soil profile from which N is acquired.

Because of the difference in 15N signatures between N2-fixing plants and non-N2-fixing plants, natural abundance 15N signatures have the potential to shed light on the dependence of different plants on recently fixed N. It is commonly assumed that plants relying exclusively on N2 fixation have δ15N of 0 ‰ (Robinson 2001), although this assumption should be checked against cultivation of the plants in an N-free medium (Shearer and Kohl 1986). The fact that N2-fixing plant δ15N is approximately 0 ‰ has been used in mixing models to calculate the quantitative dependence of plants on N2 fixation. The fraction of N derived from atmospheric N2 is given by the following mixing model:

where δ15Nref is the δ15N for a reference plant that does not depend on N2 fixation, δ15Nfix is the δ15N of a plant relying only on N2 fixation (often assumed to be 0 ‰) and δ15Ntarget is the δ15N of the species for which dependence is being calculated (Shearer and Kohl 1986). Although this measurement has been widely applied, it can at best be considered an estimate. Finding a reference plant that is using the same soil N pool as the target species may be challenging. Uncertainty in the signature of N2-fixing plants and determination of the signatures of non-N2 fixing plants greatly reduces the utility of this approach. In addition, estimates of the signatures of plants need to include more than just the signature of foliar N when it is unrepresentative of the whole plant isotopic signature (Bouillet et al. 2008). Given the sensitivity of the two-pool mixing model to the signatures of either end member, the difference of even just 1 ‰ could have large effects on estimates.

Interpreting plant δ15N as an indicator of N availability

N availability drives a significant amount of variation in plant δ15N at local to regional scales. When N supplies are high relative to demand by plants and microbes, N accumulates in inorganic pools. Larger pools of NH4 + increase the likelihood of NH3 volatilization and/or nitrification, which both increase the δ15N of remaining inorganic pools. When NO3 − pools are high, denitrification may also be more likely, which again can enrich the remaining inorganic pools in 15N. Plants that experience greater N availability may reduce their dependence on mycorrhizal fungi. This reduced dependence on mycorrhizal fungi can enrich plants by reducing the depletion associated with N transfers from mycorrhizal fungi (Högberg et al. 2011). As N availability increases relative to C, soil microbial biomass is likely to become more enriched in 15N, given greater N dissimilation compared to N assimilation, and the discrimination against 15N associated with dissimilation (Dijkstra et al. 2008). Yet, the subsequent enrichment from gaseous N losses likely overrides this depleting factor.

N fertilization studies demonstrate that plants become enriched in 15N as N availability increases. For example, an understory grass species in fertilized forest plots was enriched in 15N by more than 11 ‰ relative to control plots (Johannisson and Högberg 1994). In a separate study, loblolly pine needles became enriched by as much as 5 ‰ with N fertilization (Choi et al. 2005).

Plant δ15N also increases with increasing N availability across natural N supply or N availability gradients. In the Smoky Mountains, Tennessee, forests with high potential N mineralization had leaves that were enriched in 15N by approximately 3 ‰ relative to stands with low potential N mineralization rates (Garten and Van Miegroet 1994). Craine et al. (2009) examined relationships between metrics of N supply or availability and foliar δ15N across 15 studies. Consistently, when N supply or availability was measured in situ, δ15N increased with N availability (Fig. 4). There was less of a consistent relationship when N mineralization was measured as potential rates under standardized conditions in the laboratory—positive correlations with δ15N were only reported in 3 of the 5 studies (Craine et al. 2009).

Effect leverage plots of standardized N supply and foliar δ15N from nine studies after accounting for differences in mean foliar δ15N among sites (Craine et al. 2009). N supply was measured either as in situ N mineralization or with resin bags and standardized between 0 and 1 for each study. y = −3.09 + 3.59x; r2 = 0.25, P < 0.001

Because sites with higher N availability are more likely to have plants with higher N concentration, plant N concentration tends to correlate positively with plant δ15N. At a global scale, foliar δ15N increased logarithmically with increasing leaf N concentrations. On average, plants with foliar N concentrations of 40 mg N g−1 were enriched in 15N by 4 ‰ more than plants with just 10 mg g−1 N (Craine et al. 2009). Stronger patterns can be present at local scales. For example, across 371 non-leguminous species in a tallgrass prairie, plants with foliar N concentrations of 40 mg N g−1 were 6.1 ‰ higher than plants with just 10 mg N g−1 (Craine et al. 2012).

Soil organic matter N isotopes

The processes that lead to variation in the isotopic ratio of SOM largely overlap with those for plants. Losses of depleted N from available pools enrich the remaining available N pool, which would enrich plants and microbes as well as the organic matter they produce. Yet, as soil organic matter turns over on slower time scales than plant organic matter, SOM δ15N is likely to reflect longer term processes than plant δ15N. In this section, we focus on the patterns of δ15N in SOM within and across soils as well as the likely mechanisms that generate these patterns.

Local and global range of soil organic matter δ15N

In the first broad survey of the δ15N of SOM, Shearer et al. (1978) analyzed SOM δ15N from over 100 soils from 20 US states. They examined the relationships between SOM δ15N and climate, depth, soil pH and land use. They reported that the average δ15N of SOM was 9.2 ‰ with 90% of the samples ranging from 5 to 12 ‰, but could detect few geographic patterns.

Since the initial surveys of Shearer et al. (1978), our understanding of the patterns of SOM δ15N and the mechanisms that underlie them has progressed substantially. Whereas Shearer et al. (1978) observed just 7 ‰ variation in the δ15N of SOM, the global range of non-fertilized surface SOM δ15N has now been quantified at ~30 ‰. The highest surface soil δ15N recorded was 22.0 ‰ collected in South African fynbos on the Cape Peninsula (M. Cramer, unpublished). The highest surface SOM δ15N not adjacent to marine ecosystems was 17.7 ‰, which was in the arid lowlands of Ethiopia (Terwilliger et al. 2008). The lowest surface SOM δ15N was −7.8 ‰, collected from organic soils on moist acidic tundra (Bret-Harte et al. 2008). Among non-marine surface soils, 99% of the surface soil δ15N samples fell within 17.6 ‰ (−5.0 ‰–12.6 ‰) and 95% of the samples fell within 14 ‰ (−3.5 ‰–10.5 ‰).

Local variation in SOM δ15N has not been quantified as well as it has been for plants. Nevertheless, the δ15N of surface SOM varied by as much as 16 ‰ along a 300-m transect in Zambian woodland savanna (Wang et al. 2013). When aggregated to the 0.1° latitude/longitude scale, the range of surface soil δ15N increases logarithmically with increasing sampling density, but is independent of climate (Fig. 1; P > 0.05 for MAT, MAP) (Craine et al. 2015). With 10 samples, the range is 4.1 ‰. With 100 samples, the range is 7.6 ‰.

15N patterns related to litter and soil organic matter decomposition

Multiple studies of litter decomposition have demonstrated that litter δ15N increases as decay proceeds. In a field decomposition study of grass and hardwood tree roots, the δ15N of root litter increased by 1–3 ‰ over 5 years (Connin et al. 2001). Changes in isotopic composition during decomposition and microbial processing of leaf litter and SOM can vary with duration of incubation, differences in the mechanisms and controls on rates of decay, sequence of degradation of chemical compounds, and degree of incorporation of microbial biomass and residues.

Although loss of depleted N enriches organic matter throughout the continuum from litter to SOM, the early stages of decomposition can be associated with reductions in δ15N as 15N-depleted N is imported into microbial biomass. In one of the first studies of chemical changes during litter decomposition, the litter of pine needles decreased in δ15N by 2 ‰ as relatively 15N-depleted N was immobilized into litter over the first 22 months of decomposition (Melillo et al. 1989). Once net N mineralization began, N content of the litter began to decline and the δ15N of the litter began to increase.

During the initial stages of decomposition, the δ15N of organic matter can increase or decrease. The direction of change in N isotopic composition during litter decay result from differences in the degree of decomposition and nutrient availability. During the first year of a 2-year field incubation study of Sphagnum litter in a peatland, samples incubated in the oxic zone showed greater 15N enrichment than litter in the anoxic zone (Asada et al. 2005). During a 3-year decay study in an alpine bog, Sphagnum showed enrichment in δ15N while two vascular plant species showed declines in δ15N (Bragazza et al. 2010). Spartina biomass decaying in salt-marsh sediments also has exhibited declines in δ15N over 18 months (Benner 1991).

The enrichment in δ15N during organic matter decomposition is often attributed to incorporation of microbial biomass and residues into decaying litter and SOM. Over the course of a 6-month laboratory incubation of a cultivated soil, soil microbial biomass became significantly 15N-enriched relative to bulk soil, while water-soluble N became 15N-depleted (Lerch et al. 2011). The relationship between the ratio of microbial biomass enrichment relative to the water-soluble fraction and the C:N ratio of the water-soluble fraction followed an exponential decay model, indicating that the enrichment factor stabilized over the length of the incubation. The degree to which organic matter becomes enriched in 15N during decay is likely influenced by the C- vs. N-limited status of the microbes performing the decomposition (Dijkstra et al. 2008), with enhanced 15N enrichment of microbial biomass reflecting an increasing degree of N dissimilation linked to relative C limitation. This effect is driven in large part by discrimination against 15N during transformations of organic N to NH4 +, equilibrium isotope effects as NH4 + and NH3 experience state changes, and discrimination against 15N during subsequent loss of NH3 from the cell.

Patterns among soil organic matter fractions

Trends in isotopic composition of SOM pools are consistent with enrichment in δ15N with progressive decay and microbial alteration. Increasingly, conceptual models of SOM assume that most SOM in mineral soils is composed of microbially-processed OM (Gleixner 2013; Liang and Balser 2010; Schmidt et al. 2011). Hence, SOM with longer residence times in soil are expected to reflect isotopic signature of decomposers more than of initial plant litter inputs. Consistent with this idea, SOM fractions generally show increasing values of δ15N with decreasing particle size and increasing density or increasing mineral association (Baisden et al. 2002b; Billings 2006; Liao et al. 2006; Marin-Spiotta et al. 2009). For example, in a clay-rich tropical Oxisol, the δ15N of SOM fractions increases with increasing microbial processing as evidenced by greater δ15N of low C:N fractions (Fig. 5).

Patterns in δ15N and C:N concentrations of leaf litter and SOM physical density fractions across forests and pastures on highly-weathered Oxisols (0–10 cm) in the wet subtropical forest life zone of Puerto Rico. The degree of microbial decomposition generally increases from plant litter, Free LF (FLF; light fraction or particulate organic matter); occluded or intra-aggregate light fraction (OLF); and heavy fraction (HF; > 1.85 g/ml density. Data from Marín-Spiotta (2008)

Liao et al. (2006) quantified the C and N isotopic ratios of soils from sites where C3 trees and shrubs replaced C4 grasslands. Different physically-separated fractions of the soils varied by 6 ‰. The silt and clay fractions were most enriched in δ15N and also had the longest radiocarbon-based mean residence times, suggesting stabilization of highly-processed organic matter in the fine-sized physical fractions. Similar patterns were observed in a highly-weathered wet tropical forest soil (Marin-Spiotta et al. 2009; Marín-Spiotta et al. 2008). The decline in C:N ratios typically seen with increasing SOM fraction δ15N was associated with plant litter decay and incorporation of microbial biomass and products, as well as an increase in C mean residence time. In a study describing SOM chemistry in four soils representing a range of mineralogy and climate, Sollins et al. (2009) reported increases in δ15N and decreases in C:N ratios with increasing density across a series of physical fractions that isolated organic matter of increasing radiocarbon mean residence time associated with different mineral types. Along a soil chronosequence in California annual grasslands, declining C:N and increasing δ15N by up to 3 ‰ were observed with increasing mineral association in sequential density fractions (Baisden et al. 2002b). By using time-series to quantify multiple pool sizes and residence times, rather than a mean residence time, this study found that changes in C:N and δ15N were associated with pool size and might therefore reflect the degree of microbial transformation during mineral stabilization processes. Further supporting the idea of N isotopic enrichment with SOM transformations, Kramer et al. (2003) demonstrated a strong positive relationship between a common index of organic matter decomposition and microbial alteration, the alkyl-to-O-alkyl C ratio, and δ15N in bulk soils and physical density SOM fractions.

The overall δ15N signature of soils will depend on the signatures and the relative abundance of different fractions. For example, in a forest soil profile, most soil N (75–86%) was located in aggregates (Huygens et al. 2008). Consequently, values of δ15N bulk soil were closely related to values of aggregates and displayed an increasing trend with increasing soil depth.

Patterns of soil organic matter δ15N with depth

Variation in δ15N with depth was shown early on to be substantial. Along an elevational gradient, Mariotti et al. (1980) showed that soil at just 50 cm deep can be enriched by up to 9 ‰ relative to surface soils. Wang et al. (2009) showed that soil at 90-cm depth can be enriched by up to 17.2 ‰ relative to surface soil in an African savanna. In a review of a global distribution of 88 soil profiles, Hobbie and Ouimette (2009) showed that δ15N of SOM at 50 cm depth was enriched relative to surface litter by 9.6 ‰ for soils under ectomycorrhizal plant species and by 4.6 ‰ for plants under arbuscular mycorrhizal species. In contrast, in arid and semi-arid systems where soil pH is high, surface δ15N values can be elevated by as much as 7 ‰ relative to deeper soils (Pataki et al. 2008).

The depth distribution of the δ15N of SOM in a given soil profile is largely considered a function of the signature of inputs and losses that occur during the decomposition processes. Surface SOM δ15N values typically are dominated by the δ15N of incoming litterfall and root inputs. These vegetative components, in turn, exhibit δ15N signatures indicative of their N source and internal allocation and re-allocation of N supplies (Robinson 2001). Assuming transport is generally downward, decomposition processes become a more dominant influence on soil δ15N deeper in the soil profile – an effect that has been modeled consistently using C and N isotopes and abundances (Baisden et al. 2002a). As SOM age tends to increase with depth (Trumbore 2000, 2009), many studies assume that the degree of microbial processing of SOM generally increases with depth. Consistent with this, soil C:N tends to decline with depth (Marín-Spiotta et al. 2014) and SOM δ15N often increases (Billings and Richter 2006; Compton et al. 2007; Piccolo et al. 1996). As discussed above, this is typically assumed to result from the fractionation associated with decay and microbial assimilation or dissimilation of N, with resulting 15N-depletion or enrichment of microbial biomass, respectively (Dijkstra et al. 2006).

Although large contributions of microbial necromass to SOM are likely ubiquitous, their effect on soil profile δ15N may be outweighed by the effect of gaseous losses dominating soil N cycling in surface soils. For example, Pataki et al. (2008) attributed 15N enrichment of an alkaline soil in an arid ecosystems to ammonia volatilization and its large enrichment factor. It remains unclear whether this feature is ubiquitous in alkaline soils where NH3 volatilization is a dominant process, or why other fractionating losses of nitrogenous gases (e.g., N2O) do not appear to result in similar profiles.

In soils supporting aggrading forests with high vegetation nutrient demand, SOM decomposition can outweigh SOM formation (Richter et al. 1999). In these soils, increases in soil δ15N with SOM decay can become evident within years, and during forest development, agriculturally well-mixed soil profiles can attain the vertical 15N distribution typically seen in less disturbed profiles over decades (Billings and Richter 2006). This rapid shift in soil δ15N with forest development is attributed to the accumulation of 15N-enriched microbial necromass and, to a lesser extent, fractionation effects during SOM decay.

The mycorrhizal association of the dominant plant species is another important factor in explaining variation in vertical patterns of δ15N in soils. Hobbie and Ouimette (2009) showed that almost all soil under ectomycorrhizal species had monotonically increasing soil δ15N, while 40% of the AM sites had the highest δ15N at intermediate depth. There were no strong relationships between climate and the pattern of soil δ15N with depth. Also, soils with higher nitrification rates did not appear to have greater vertical distributions of soil δ15N.

Vertical patterns in soil δ15N also have the potential to be influenced by hydrologic movement of N. In a Hawaiian tropical rain forest, Marin-Spiotta et al. (2011) reported a soil 15N profile with maximum δ15N at intermediate depths. They attributed this pattern to differences in drainage and microbial processing in the upper and lower soil profile due to the presence of cemented or placic layers forming along hydrologic flow paths. Differences in the δ15N above and below these layers were consistent with patterns in soil C:N ratios and the accumulation of organic matter at depth with isotopic and chemical signatures more similar to the surface organic horizons. Thus, differences in decomposition (and the losses that occur therein) and the transport in preferential flowpaths of recent, surface organic matter to deeper mineral soil layers in very wet sites, with poor drainage, or with high shrink-swell capacity soils can also lead to vertical soil δ15N profiles that differ from the more commonly observed enrichment with depth.

Interpreting differences between plant and soil δ15N

One of the most important steps in moving forward is an assessment of the relative merits of soil δ15N, plant δ15N, or the difference between the two for interpreting patterns of δ15N. The difference between plant δ15N and soil δ15N is generally referred to as the enrichment factor (Mariotti et al. 1981). It is called an “enrichment” factor based on the assumption that plant N is the end product of a series of enriching reactions that begin with soil organic matter. It is thought that standardizing patterns of plant δ15N for underlying variation in δ15N of SOM will remove variation in the signature of the source of δ15N and better reveal N cycling patterns.

There are cases where enrichment factors appear to be better indicators than soil 15N of N cycling rates among ecosystems. Emmett et al. (1998) compared enrichment factors among coniferous forests in order to normalize initial differences in soil δ15N values for effect of land management practices, soil age, and climate. Among sites, surface soil δ15N varied by ~6 ‰. Calculating the enrichment factor for these sites led to better relationships with N availability metrics than foliar δ15N.

When examined globally, plants are almost always more depleted in 15N than soils. When comparing site-averaged foliar δ15N and δ15N of SOM (typically 0–20 cm) with data from Craine et al. (2009), in 92% of the sites, foliar δ15N was less than that of soils (average difference of 3.3 ‰). Ericoid plants were the most depleted relative to SOM on average (−4.9 ± 0.2 ‰) with ectomycorrhizal plants (−4.0 ± 0.1 ‰) and arbuscular plants (−3.4 ± 0.1 ‰) showing similar levels of relative depletion. Even non-mycorrhizal plants were still depleted on average (−0.6 ± 0.2 ‰). Craine et al. (2009) reported that sites with high foliar δ15N also had a large absolute difference between the δ15N of leaf and SOM.

At the global scale, leaves are more depleted in 15N than soils across the global climate spectrum even when factoring out mycorrhizal influences. To compare the global relationships between leaves and SOM, average SOM δ15N was determined for 901 locations at the global scale assuming a depth of 30 cm using the data from Craine et al. (2015). In order to predict foliar δ15N at each of these locations, we used the data from Craine et al. (2009) to establish relationships between foliar δ15N and climate parameters (MAT, MAP) for plants of different mycorrhizal types assuming each plant had the global mean foliar N concentration in the dataset of 16.2 mg N g−1 (Craine et al. 2009). This allows one to calculate the δ15N of a plant of a given mycorrhizal type anywhere in the global climate space. Given the soil δ15N and predicted foliar δ15N at each of the 901 locations, soils were more enriched than plants in 74% of the sites for the typical non-mycorrhizal plant and 99.9% of the sites for ericoid plants (Fig. 6).

Relationship between mean annual temperature (MAT) and the difference between the δ15N of leaves and soils (0–30 cm). Predicted leaf δ15N calculated for non-mycorrhizal plant with a foliar [N] of 16.2 mg g−1 at the same mean annual temperature and precipitation of soil. Soil data represent average soil δ15N averaged for 901 0.1° latitude and longitude grid cells (Craine et al. 2015). Solid line represents same signature of leaves of non-mycorrhizal plant and soils. All points below line would have lower δ15N in leaves than soils. To compare with other mycorrhizal types, dashed line shows expected difference between leaves of ericoid mycorrhizal plants, which are most depleted in 15N relative to non-mycorrhizal plants, and soils

Three hypotheses have been offered to explain the consistent depletion of leaves relative to soils. First, solubilization of N leads to greater isotopic fractionation than previously thought. As discussed earlier, work on the signatures of microbial biomass suggest that there are additional fractionation factors associated with mineralization that had not previously been considered when comparing plants and soils. Still, more research and modeling is needed to determine the potential influence of microbial enrichment on the net 15N depletion of plants. Second, mycorrhizal transfers of N and fractionation during these transfers is stronger than previously thought. Although average differences among mycorrhizal types have been assessed, there are still uncertainties regarding the magnitude of fractionation under different conditions and the degree to which utilization of different forms of N contributes to the variation in δ15N among plant species with different mycorrhizal symbioses. Third, the δ15N of bulk SOM is not a good indicator of the signature of the pool that serves as a source of N to plants. Associated with differences in turnover, inorganic N is more likely to come from the relatively depleted non-mineral-associated pools rather than the enriched, mineral-associated pools. Critical knowledge gaps remain if we want to quantify the signatures of available N. More research is needed to link the signature of different SOM fractions and the source of N for plant and microbial uptake.

In order to link enrichment factors to N status or N availability, a number of conditions would have to be met or accounted for. Regarding sources of N, deposition would have to be a small source of N or have a similar signature as SOM. The greater 15N enrichment of high-clay soils may make it seem like there is a lower enrichment in plants relative to SOM on high-clay soils than low-clay soils.

When comparing the signature of plants, both the depth of N acquisition and mycorrhizal type would have to be standardized. The presence of N fixers can also skew enrichment factors between soils and plant δ15N. N2-fixing plants are typically excluded from calculations of average plant δ15N, but rely on soil-derived N, too. Any difference in the signatures of N acquired by non-N2-fixing and N2-fixing plants would alter the calculated enrichment factor.

Although enrichment factors have been useful in determining N availability in some ecosystems, their application can be limited by the aforementioned processes that lead to variability in source N. Broad, cross-site studies that measure N cycling parameters as well as SOM and plant δ15N are relatively rare. Given the difficulty in comparing N supplies or availability across broad contrasts where N is cycled fundamentally differently, e.g., organically vs. inorganically, the utility of enrichment factors to assess differences in N availability is unlikely to be tested soon. Instead, this technique is more likely to be useful across narrow contrasts with little variation in other factors. Specific interpretations of plant δ15N, soil δ15N, or enrichment factors will still need to occur on a case by case basis.

Interpreting N isotope patterns across climate gradients

As plant and soil δ15N data have accumulated, δ15N patterns and their interpretations have changed over time generating some confusion on how N cycling parameters might be changing along climate gradients. The first attempt to broadly synthesize relationships between climate and plant δ15N was by Handley et al. (1999a) who found that foliar δ15N declined linearly with increasing rainfall across 97 sites. Their working hypothesis to explain this pattern followed Austin and Vitousek (1998): dry sites have a more “open” N cycle with a greater importance of inputs and outputs compared to within-system cycling. Although Handley et al. found no influence of latitude on foliar δ15N, Martinelli et al. (1999) reported that tropical leaves averaged 6.5 ‰ higher δ15N than temperate leaves (3.7 vs. -2.8 ‰). These authors proposed a similar explanation, that tropical forests typically have a more “open” N cycle, with large inputs and outputs of N relative to internal N cycling.

Amundson et al. (2003) synthesized foliar δ15N from 106 sites and demonstrated that foliar δ15N increased with increasing mean annual temperature (MAT) and decreasing mean annual precipitation (MAP). They interpreted these patterns as indicating that hot, dry sites have both a greater proportion of N being lost through fractionating pathways and a more open N cycle. The authors suggested that because most undisturbed soils are near N steady state, an increasing fraction of ecosystem N losses with decreasing MAP and increasing MAT were 15N-depleted forms (NO3, N2O, etc.). They concluded that wetter and colder ecosystems appeared to be more efficient in conserving and recycling mineral N.

A subsequent study of over 11,000 non-N2 fixing plants at the global scale found that foliar δ15N increased logarithmically with decreasing MAP (Craine et al. 2009). Foliar δ15N increased linearly with increasing MAT, but only for those ecosystems with MAT > −0.5°C. Due to linkages observed at local scales between N availability and foliar δ15N, these global relationships between climate and foliar δ15N were interpreted to suggest higher N availability in warm, dry ecosystems.

As was the case for plants, observations of the patterns of soil δ15N with climate and their explanations have shifted over time. After the Shearer et al. (1978) synthesis of North American soils, there was a 20-year gap in synthesizing soil δ15N. In 1999, two papers were published that began to frame global patterns of soil 15N with respect to climate (Handley et al. 1999a; Martinelli et al. 1999). Handley et al. demonstrated that across 47 soils, low-latitude sites had lower δ15N in SOM from surface mineral soils. With a different set of soils, Martinelli et al. showed the opposite pattern—tropical soils were more enriched in δ15N than temperate soils. Combining the data of previous studies, Amundson et al. (2003) reported that average soil δ15N followed similar patterns as foliar δ15N. Across 47 soils, average soil δ15N to 50 cm increased with increasing MAT and decreased with increasing MAP (P < 0.1). This further supported their conclusion of greater proportions of fractionating losses in hot, dry ecosystems compared to the “more efficient” cold, wet ecosystems.

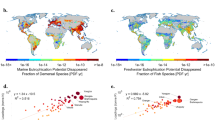

On the other hand, an extensive dataset of soil δ15N that included key covariates (soil C and clay concentrations) suggests different mechanisms at work (Craine et al. 2015). Across 6,000 soil samples that were aggregated to 910 locations (0.1° latitude and longitude), the δ15N of surface mineral soils was greater for sites with high MAT and low MAP, but there was no relationship between SOM δ15N and MAT across ecosystems with MAT < 9.8°C. Soil δ15N increased with decreasing C and N concentrations as well as decreasing C:N, similar to what is observed with increasing decomposition of organic matter and soil depth. Organic soils with a [C] of 450 mg C g−1 soil on average had a δ15N of −0.2 ‰. Mineral soils with a [C] of 200 mg C g−1 soil on average had a δ15N of 3.1 ‰. Mineral soils with a [C] of 20 mg C g−1 soil on average had a δ15N of 5.0 ‰. In addition to soils with lower [C] being more enriched in δ15N, soils with higher clay concentrations were also more enriched in 15N in a parallel manner to differences among soil fractions that differ in clay content. Across soils, increasing clay concentrations by an order of magnitude increases soil δ15N by 2.0 ‰.