Abstract

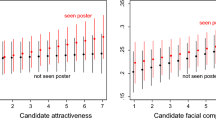

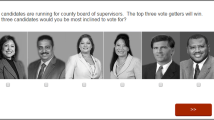

According to numerous studies, candidates’ looks predict voters’ choices—a finding that raises concerns about voter competence and about the quality of elected officials. This potentially worrisome finding, however, is observational and therefore vulnerable to alternative explanations. To better test the appearance effect, we conducted two experiments. Just before primary and general elections for various offices, we randomly assigned voters to receive ballots with and without candidate photos. Simply showing voters these pictures increased the vote for appearance-advantaged candidates. Experimental evidence therefore supports the view that candidates’ looks could influence some voters. In general elections, we find that high-knowledge voters appear immune to this influence, while low-knowledge voters use appearance as a low-information heuristic. In primaries, however, candidate appearance influences even high-knowledge and strongly partisan voters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Several other observational results are inconsistent with the alternative explanation emphasizing the causal influence of campaign effort entirely explaining the observed effect of candidate appearance. Specifically, the effect of the candidate’s appearance holds when professional photographers took the pictures in a standard format (Antonakis and Dalgas 2009; Klein and Rosar 2005), and when one statistically controls for differences in image quality and other aspects of the pictures, such as visible light (Lawson et al. 2010; Rosar et al. 2008). Additionally, appearance-advantaged candidates win in competitive races, where the candidates should be more comparable in quality and in resources (Antonakis and Dalgas 2009; Benjamin and Shapiro 2009). They also perform disproportionately well in systems where legislators compete against members of the same party (Berggren et al. 2010) and in non-partisan contests (Banducci et al. 2008; Martin 1978).

In general, researchers should not control for variables that intervene between the treatment and the outcome, in this case, between candidate appearance and vote share. For a general discussion, see King (1991, 1049–50).

When estimating the effect of challenger appearance, Atkinson et al. (2009) carefully try to avoid post-treatment bias by measuring district competitiveness at least 1 year before the general election, when the challenger's identity is less clear (using the Cook Political Report). Nevertheless, these experts may already know the likely challengers and so may be influenced by their looks (making these ratings post-treatment).

Indeed, Atkinson et al. (2009, 236) are careful not to interpret their regression coefficient for incumbent appearance as a causal estimate. They suggest instead that appearance-advantaged incumbents (as challengers in a prior election) disproportionately select into competitive districts, which would bias their estimate of incumbent appearance downwards. This downward bias and, more generally, the causal complexity of observational studies on appearance provide reasons to turn to experimental studies such as ours.

Of course, candidates’ efforts to “improve” their appearance, as revealed through their photos, may contribute to any such causal effects.

We also ran the experiment in six California State Senate races. We do not pool these races with the House primaries in the analysis because photograph quality was noticeably lower. Instead, we present these results in OA section 1.2. Including them in the main analysis leaves our key findings unchanged.

No matter what measure of appearance we choose, that measure will also pick up other characteristics that correlate with it. One way to break these correlations would be to artificially alter candidate photos in order to experimentally vary these traits, but using altered photos would significantly reduce the external validity of our experiments. We thus use actual candidate photos and make no claim about the particular aspect of a candidate’s appearance that influences voters.

The authors and a team of research assistants used endorsements, campaign finance data, previous office, number of competing co-partisans, and vote share in previous elections to classify candidates as viable or nonviable before the election. These assessments were largely holistic but are validated by the actual election results: A nonviable-classified candidate finished ahead of a viable-classified candidate in just 2 of the 13 races under study here, and neither of those candidates came close to advancing to the general election.

Ideally, we would address race and gender not with controls but by restricting the analysis to candidates matched on race and gender, but only three of the 14 races in Study 1 were so matched. We are, however, able to conduct this analysis in the second study.

Finally, to address separate concerns about candidate vote share not being independently distributed within district, OA section 4.6 shows that the photo-ballot respondents were 10 percentage points more likely to vote for the most appearance-advantaged candidate in their district compared to control ballot respondents (p < 0.001).

Survey dates: October 17-November 2. Election Day was November 6. We also asked participants about a handful of multicandidate races and single-candidate judicial retention elections. Since analyzing races with only one or more than two candidates introduces complications, we relegate analysis of these races to the OA (see OA section 5.1). The results are consistent with the overall findings in the paper.

Research has found differential effects of candidate appearance where one or both candidates are female (Chiao et al. 2008; Poutvaara et al. 2009). Unfortunately, we lack a sufficient number of races to shed further light on this topic (half of the races are male-male and the other half are mostly female-male races).

Another interpretation of the finding is that candidate age—as discerned from the pictures—influences treated participants to change their votes. Previous studies, however, have found that controlling for age, using various functional forms, leaves the appearance-vote relationship unchanged (Lawson et al. 2010, 581; Todorov et al. 2005).

Several classroom and lab studies have conducted experiments on appearance effects (e.g.,Johns and Shephard 2007; Rosenberg and McCafferty 1987; Spezio et al. 2008). Our experiment builds on these by examining whether candidate appearance can influence real-world voters' decisions in actual elections.

We also tested for over time patterns in Study 1. Since we conducted Study 1 over fewer days and since primary campaigns usually pale in comparison to general election campaigns, we might not expect to see such patterns, which is what we find.

We estimate this by multiplying candidate appearance advantage by the appearance effect reported in Column 1 of Table 2, adding the constant to the outcome, and then subtracting that result from the candidate’s actual vote share in the 2012 election.

We use linear probability models because they are consistent under weak assumptions and the estimates are simpler to interpret, especially with interaction terms (Ai and Norton 2003).

In OA sections 4.3–4.5, we find evidence that strong partisanship can diminish the appearance effect, especially among high-knowledge individuals. We find this in downballot races (no senatorial and gubernatorial races) and when we substitute local for general knowledge.

Unpublished work by one of the authors finds that competent looking incumbents are no more effective in Congress, nor are they evaluated as being more effective by peers in the North Carolina legislature (see OA section 6).

References

Ahler, D. J., Citrin, J., & Lenz, G. S. (2016). Do open primaries improve representation? An experimental test of california’s 2012 top-two primary. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 41(2), 237–268.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Alley, T. R. (1988). Social and applied aspects of perceiving faces, resources for ecological psychology. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Andreoni, J., & Petrie, R. (2008). Beauty, gender and stereotypes: Evidence from laboratory experiments. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 73–93.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Antonakis, J., & Dalgas, O. (2009). Predicting elections: Child’s play! Science, 323(5918), 1183.

Atkinson, M. D., Enos, R. D., & Hill, S. J. (2009). Candidate faces and election outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 4(3), 229–249.

Ballew, C. C, I. I., & Todorov, A. (2007). Predicting Political Elections from rapid and unreflective face judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(46), 17948–17953.

Banducci, S. A., Karp, J. A., Thrasher, M., & Rallings, C. (2008). Ballot photographs as cues in low-information elections. Political Psychology, 29(6), 903–917.

Bar, M., Neta, M., & Linz, H. (2006). Very first impressions. Emotion, 6(2), 269–278.

Belot, M., Bhaskar, V., & Van De Ven, J. (2012). Beauty and the sources of discrimination. Journal of Human Resources, 47(3), 851–872.

Benjamin, D. J., & Shapiro, J. M. (2009). Thin-slice forecasts of gubernatorial elections. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(3), 523–536.

Berggren, N., Jordahl, H., & Poutvaara, P. (2010). The looks of a winner: Beauty and electoral success. Journal of Public Economics, 94(1–2), 8–15.

Brusattin, L. (2012). Candidate visual appearance as a shortcut for both sophisticated and unsophisticated voters: Evidence from a Spanish online study. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24(1), 1–20.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Chiao, J. Y., Bowman, N. E., & Gill, H. (2008). The political gender gap: Gender bias in facial inferences that predict voting behavior. PLoS ONE, 3(10), e3666.

Cohen, R. (1973). Patterns of personality judgment. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent. New York: Free Press.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fletcher, J. M. (2009). Beauty vs. brains: Early labor market outcomes of high school graduates. Economics Letters, 105(3), 321–325.

Hall, C. C., Goren, A., Chaiken, S., & Todorov, A. (2009). Shallow cues with deep effects: Trait judgments from faces and voting decisions. In E. Borgida, C. M. Federico, & J. L. Sullivan (Eds.), Political psychology of democratic citizenship (pp. 73–99). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hamermesh, D. S. (2006). Changing looks and changing “discrimination”: The beauty of economists. Economics Letters, 93(3), 405–412.

Hamermesh, D. S. (2011). Beauty pays: Why attractive people are more successful. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Hamermesh, D. S., & Parker, A. (2005). Beauty in the classroom: Instructors’ pulchritude and putative pedagogical productivity. Economics of Education Review, 24(4), 369–376.

Hassin, R., & Trope, Y. (2000). Facing faces: Studies on the cognitive aspects of physiognomy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 837–852.

Johns, R., & Shephard, M. (2007). Gender, candidate image and electoral preference. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 9(3), 434–460.

Kalick, S. M., Zebrowitz, L. A., Langlois, J. H., & Johnson, R. M. (1998). Does human facial attractiveness honestly advertise health? Longitudinal data on an evolutionary question. Psychological Science, 9(1), 8–13.

Key, V. O. (1966). The responsible electorate: Rationality in presidential voting, 1936–1960. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

King, G. (1991). “Truth” is stranger than prediction, more questionable than causal inference. American Journal of Political Science, 35(4), 1047–1053.

King, A., & Leigh, A. (2009). Beautiful politicians. Kyklos, 62(4), 579–593.

Klein, M., & Rosar, U. (2005). Physische Attraktivität Und Wahlerfolg. Eine Empirische Analyse Am Beispiel Der Wahlkreiskandidaten Bei Der Bundestagswahl 2002. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 46(2), 263–287.

Krasno, J. S. (1997). Challengers, competition, and reelection: Comparing senate and house elections. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kuklinski, J. H., & Quirk, P. J. (2000). Reconsidering the rational public. In A. Lupia & M. D. McCubbins (Eds.), Elements of reason: Cognition, choice, and the bounds of rationality (pp. 153–182). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Laskas, J. M. (2012). Bob dole: Great American. GQ(July), 54, 88–90.

Lawson, C., Lenz, G. S., Myers, M., & Baker, A. (2010). Looking like a winner: Candidate appearance and electoral success in new democracies. World Politics, 62(4), 561–593.

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lenz, G. S., & Lawson, C. (2011). Looking the part: Television leads less informed citizens to vote based on candidates’ appearance. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 574–589.

Lupia, A. (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. American Political Science Review, 88(1), 63–76.

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they really need to know?. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, D. S. (1978). Person perception and real-life electoral behaviour. Australian Journal of Psychology, 30(3), 255–262.

Mattes, K., Spezio, M., Kim, H., Todorov, A., Adolphs, R., & Alvarez, R. M. (2010). Predicting election outcomes from positive and negative trait assessments of candidate images. Political Psychology, 31(1), 41–58.

Nelson, C. M. (2012). In denver, clinton says romney plan ‘doesn’t add up. Wall Street Journal Blog. Accessed April 2013. http://blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2012/10/31/in-denver-clinton-says-romney-plan-doesnt-add-up.

Olivola, C. Y., & Todorov, A. (2010). Elected in 100 Milliseconds: Appearance-based trait inferences and voting. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34(2), 83–110.

Popkin, S. L. (1991). The reasoning voter: Communication and persuasion in presidential campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Poutvaara, P., Jordahl, H., & Berggren, N. (2009). Faces of politicians: Babyfacedness predicts inferred competence but not electoral success. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(5), 1132–1135.

Ravina, E. (2012). Love & loans: The effect of beauty and personal characteristics in credit markets. Available at SSRN 1101647.

Riggio, H. R., & Riggio, R. E. (2010). Appearance-based trait inferences and voting: Evolutionary roots and implications for leadership. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34(2), 119–125.

Rosar, U., Klein, M., & Beckers, T. (2008). The frog pond beauty contest: Physical attractiveness and electoral success of the constituency candidates at the North Rhine-Westphalia state election 2005. European Journal of Political Research, 47(1), 64–79.

Rosenberg, S. W., & McCafferty, P. (1987). The image and the vote: Manipulating voters’ preferences. Public Opinion Quarterly, 51(1), 31–47.

Schaffner, B. F., & Streb, M. J. (2002). The partisan heuristic in low-information elections. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66(4), 559–581.

Spezio, M. L., Loesch, L., Gosselin, F., Mattes, K., & Alvarez, R. M. (2012). Thin-slice decisions do not need faces to be predictive of election outcomes. Political Psychology, 33(3), 331–341.

Spezio, M. L., Rangel, A., Alvarez, R. M., O’Doherty, J. P., Mattes, K., Todorov, A., et al. (2008). A neural basis for the effect of candidate appearance on election outcomes. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 3(4), 344–352.

Todorov, A., Mandisodza, A. N., Goren, A., & Hall, C. C. (2005). Inferences of competence from faces predict election outcomes. Science, 308(5728), 1623–1626.

Waismel-Manor, I., & Tsfati, Y. (2011). Why do better-looking members of congress receive more television coverage? Political Communication, 28(4), 440–463.

Wilson, R. K., & Eckel, C. C. (2006). Judging a book by its cover: Beauty and expectations in the trust game. Political Research Quarterly, 59(2), 189–202.

Zebrowitz, L. A. (1997). Reading faces. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Zebrowitz, L. A., Hall, J. A., Murphy, N. A., & Rhodes, G. (2002). Looking smart and looking good. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(2), 238–249.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luke Edwards, Aaron Kaufman, Aidan McCarthy, Tony Valeriano, and Kelsey White for research assistance and students in the fall 2012 Presidential Elections and Democratic Accountability class for help collecting candidate photos and candidate knowledge questions. We are also grateful for comments from David Doherty, Laura Stoker, conference participants at the 2013 Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting and the 2013 West Coast Experiments Conference at Stanford University, and research workshop participants at both the University of California, Berkeley and the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Finally, we thank the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley for funding. Replication code and data is available from https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/facevalue.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human Rights and Informed Consent

The studies were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) at the University of California, Berkeley. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of CPHS and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahler, D.J., Citrin, J., Dougal, M.C. et al. Face Value? Experimental Evidence that Candidate Appearance Influences Electoral Choice. Polit Behav 39, 77–102 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9348-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9348-6