Abstract

Why do politicians use violence as an electoral tactic, and how does it affect voting behavior? Theories of election-related violence focus on the electoral benefits such violence is said to provide, relying on the assumption that when parties and candidates employ violence, they do so based on an accurate assessment of its relative costs and benefits. Far less attention has been paid to the costs of violence as an electoral tactic, including the potential for voter backlash against it. This study provides evidence that voter backlash against violence is more significant than both scholars and politicians tend to assume. Moreover, that backlash can diminish the electoral advantages that violence provides. Combining survey experiments with Kenyan voters and observational data on violence and election outcomes, I find compelling evidence for broad-based voter backlash against violence that undermines its effectiveness as an electoral tactic. At the same time, data from parallel survey experiments and qualitative interviews with Kenyan politicians demonstrate that they underestimate the extent to which violence diminishes their support among voters. The results highlight the often underappreciated costs of violence as an electoral tactic and the role that elite misperceptions can play in its persistence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All data and replication code are available on the Political Behavior Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DYHANZ.

Bratton (2008), for example, finds that just 4% of voters overall, and 13% in the most affected region, experienced instances of intimidation in the quite violent 2007 elections in Nigeria.

Kapferer (1988, p. 100), for example, suggests that Sinhalese Buddhists in Sri Lanka faulted Sinhalese President Jayawardene for capitulating to Tamil interests by “not killing enough.” Horowitz (1985) and Petersen (2002) also emphasize the role of interethnic resentment and hatred in generating intergroup political violence.

See also (Hoffman & McCormick, 2004) on suicide terrorism as strategic signaling.

Collier and Vicente (2012) is a notable exception.

77% of citizens surveyed across 33 African countries for the Afrobarometer survey declared that the use of violence is never justified in their country’s politics (Afrobarometer, 2014).

Mutahi and Ruteere (2019) provide a useful analysis of the reasons why election-related ethnic violence was more limited in 2017, while state/police violence against the opposition remained intense.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, July 24, 2014.

All of the voter experiments were preregistered on the EGAP study registry. The protocol for the experiments was approved by the Yale University Human Subjects Committee (Protocol No. 1308012598), and the broader research project was approved by the Kenya National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI/P/13/8198/105) to ensure that it met local standards. Among other precautions, the voter survey was anonymous (it did not collect any identifiable information), and the informed consent script made explicit that there was no penalty for refusing to participate and that respondents could end participation at any time or refuse to answer any individual question.

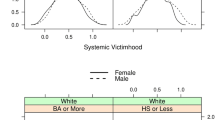

“Older” voters were those 35 and above, while “more educated” voters were those that had completed secondary school.

Respondents had a 50% probability of being assigned a candidate from their own tribe and a 12.5% chance of being assigned a candidate from each of four other tribes so that estimated effects would not be biased by sentiments particular to one tribal out-group or another.

I ran a slightly modified version of the experiment that would make better sense when fielded countrywide as opposed to specific locations. This included increasing the number of possible candidate ethnicities to the 11 tribes that make up at least 1% of the Kenyan population. The effective sample includes only respondents from such tribes (nearly 93% of those surveyed). See Appendix C for wording.

The effect is estimated as the difference in means between the pooled violence treatments and the control group.

These results are largely consistent with the Horowitz and Klaus (2020) study on ethnic appeals in Kenya.

However, this approach cannot control for selection into treatment over time, for instance if a constituency is more likely to be subject to violence if the relevant party is gaining or losing support there.

Only 9 of the 25 districts that saw violence in the run-up to the 1992 and 1997 elections experienced such violence in both election cycles, meaning that the fixed effects framework identifies effects off of about two-thirds of violence-affected districts.

In Online Appendix B.2, I provide additional evidence that politicians’ involvement in violence can backfire, showing that politicians allegedly involved in the 2007/2008 post-election violence performed worse than comparable candidates in the following elections in 2013.

See the Online Appendix for additional information about the sample.

This eliminates the offensive/defensive violence distinction as well as the attributed/unattributed violence dimension.

Online Appendix Fig. B4 displays the results of t-tests for all four treatment conditions and both outcomes; Fig. B5 displays p-values from randomization inference using Fisher’s exact test of the sharp null hypothesis.

This analysis pools the sample of politicians and voters and estimates the difference in effects between them by interacting treatment indicators with an indicator for whether the respondent is a politician or voter. Note that the difference between politicians and voters can be statistically significant even if the null results in the politician experiments are attributable to the small sample size.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/1/14; Interview with Kenyan MCA, 5/22/15; Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/30/14.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/24/14

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/30/14; Interview with Kenyan MP, 7/8/14.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/23/14.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/23/14; Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/23/14; Interview with Kenyan MP, 7/8/14.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/30/14; Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/24/14; Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/17/14.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/17/14; Interview with Kenyan MCA, 3/19/15.

Interview with former Kenyan MP candidate, 11/21/14.

Interview with Kenyan MP, 7/1/14; Interview with Kenyan MP, 7/3/14.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/23/14; Interview with Kenyan MCA, 7/24/14.

Interview with Kenyan MCA, 5/25/15.

Interview with Kenyan MP, 11/10/14; Interview with former Kenya gubernatorial candidate, 4/9/15.

To be sure, a handful of politicians characterized voter preferences over violence more accurately. One MP suggested that “Luos will generally obviously vote for one of their own, like all other tribes in Kenya, [but] it is not assured here because of his violent ways,” while an MCA noted that the “first instinct for them [coethnic voters] will be to vote for him because, like them, he is Kalenjin, [but] the fact that he is said to be using violence will make him lose reasonable voters from his own tribe.” However, such beliefs were clearly the exception rather than the rule.

References

Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. A., & Santos, R. J. (2013). The monopoly of violence: Evidence from Colombia. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11, 5–44.

Afrobarometer. (2014). “Round 6 survey manual.”.

Akiwumi, A. M., Bosire, S. E. O., & Ondeyo, S. C. (1999). Akiwumi Report. Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Tribal Clashes in Kenya.

Anderson, D., & Lochery, E. (2008). Violence and exodus in Kenya’s rift valley, 2008: Predictable and preventable? Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 328–343.

Berenschot, W. (2012). Riot politics: Hindu-Muslim violence and the Indian State. Columbia University Press.

Boas, T. C. (2016). Presidential campaigns in Latin America: Electoral strategies and success contagion. Cambridge University Press.

Boas, T. C., Daniel Hidalgo, F., & Melo, M. A. (2018). Norms versus action: Why voters fail to sanction malfeasance in Brazil. American Journal of Political Science, 63(2), 385–400.

Boone, C. (2011). Politically allocated land rights and the geography of electoral violence: The case of Kenya in the 1990s. Comparative Political Studies, 44(10), 1311–1342.

Brass, P. R. (2003). The production of Hindu-Muslim violence in contemporary India. University of Washington.

Bratton, M. (2008). Vote buying and violence in Nigerian Election Campaigns. Electoral Studies, 27(4), 621–632.

Broockman, D. E., & Skovron, C. (2018). Bias in perceptions of public opinion among political elites. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 542–563.

Butler, D. M., & Nickerson, D. W. (2011). Can learning constituency opinion affect how legislators vote? Results from a field experiment. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 6(1), 55–83.

Cheeseman, N. (2008). The Kenyan Elections of 2007: An introduction. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 166–184.

Collier, P., & Vicente, P. C. (2012). Violence, bribery, and fraud: The political economy of elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Public Choice, 153(1–2), 117–147.

Dercon, S., & Gutiérrez-Romero, R. (2012). Triggers and characteristics of the 2007 Kenyan Electoral Violence. World Development, 40(4), 731–744.

Ellman, M., & Wantchekon, L. (2000). Electoral competition under the threat of political unrest. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 499–531.

Enos, R. D., & Hersh, E. D. (2017). Campaign perceptions of electoral closeness: Uncertainty, fear, and over-confidence. British Journal of Political Science, 47(3), 501–519.

Eyster, E., & Rabin, M. (2010). Naïve herding in rich-information settings. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 2(4), 221–243.

Fearon, J. D., & Laitin, D. D. (2000). Violence and the social construction of ethnic identity. International Organization, 54(4), 845–877.

Gerber, A. S., & Green, D. P. (2000). The effects of canvassing, telephone calls, and direct mail on voter turnout: A field experiment. American Political Science Review, 94(3), 653–663.

Gutiérrez-Romero, R. (2014). An inquiry into the use of illegal electoral practices and effects of political violence and vote-buying. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 58(8), 1500–1527.

Gutiérrez-Romero, R., & LeBas, A. (2020). Does electoral violence affect vote choice and willingness to vote? Conjoint analysis of a vignette experiment. Journal of Peace Research, 57(1), 77–92.

Harris, J. A. (2013). ’Stain removal’: Measuring the effect of violence on local ethnic demography in Kenya.

Hersh, E. D. (2015). Hacking the electorate: How campaigns perceive voters. Cambridge University Press.

Hoffman, B., & McCormick, G. H. (2004). Terrorism, signaling, and suicide attack. Studies in Conflict & Terrorisim, 27(4), 243–281.

Höglund, K., & Piyarathne, A. (2009). Paying the price for patronage: Electoral violence in Sri Lanka. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 47(3), 287–307.

Horowitz, D. L. (1985). Ethnic groups in conflict. University of California Press.

Horowitz, J., & Klaus, K. (2020). Can politicians exploit ethnic grievances? An experimental study of land appeals in Kenya. Political Behavior, 42(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9485-1.

Human Rights Watch. (1995). Kenya. In Slaughter Among Neighbors: The Political Origins of Communal Violence, chapter 7. Yale University Press.

Human Rights Watch. (2002). Playing with fire: Weapons proliferation, political violence, and human rights in Kenya. Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch. (2007). Criminal politics: Violence, “godfathers” and corruption in Nigeria.

Human Rights Watch. (2013). High stakes: Political violence and the 2013 elections in Kenya. Human Rights Watch.

Husain, N. (2002). Armed & dangerous: Small arms and explosives trafficking in Bangladesh. South Asia Intelligence Review, 1, 13–14.

Kagwanja, P. M. (2003). Facing mount Kenya or facing Mecca? The Mungiki, ethnic violence and the politics of the Moi succession in Kenya, 1987–2002. African Affairs, 102, 25–49.

Kalla, J. L., & Broockman, D. E. (2018). The minimal persuasive effects of campaign contact in general elections: Evidence from 49 field experiments. American Political Science Review, 112(1), 148–166.

Kanyinga, K. (2009). The legacy of the white highlands: Land rights, ethnicity and the post-2007 election violence in Kenya. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 27(3), 325–344.

Kanyinga, K. (2011). Stopping a conflagration: The response of Kenyan civil society to the post-2007 election violence. Politikon, 38(1), 85–109.

Kapferer, B. (1988). Legends of people, myths of state: Violence, intolerance, and political culture in Sri Lanka and Australia. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Kasara, K. (2016). Electoral geography and conflict: Examining the redistricting through violence in Kenya.

Klaus, K. (2020). Political violence in Kenya: Land, elections, and claim-making. Cambridge University Press.

Klopp, J. M. (2001). Ethnic clashes and winning elections: The case of Kenya’s electoral despotism. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 35(3), 463–517.

KNCHR. (2008). On the brink of the precipice: A human rights account of Kenya’s post-2007 election violence—Final Report. Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.

KNCHR. (2017). Still a mirage at dusk: A human rights account of the 2017 fresh presidential elections. KNCHR.

Laakso, L. (2007). Insights into Electoral Violence in Africa. In M. Basedau, G. Erdmann, & A. Mehler (Eds.), Votes, Money and Violence (pp. 224–252). University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Lau, R. R., Sigelman, L., & Rovner, I. B. (2007). The effects of negative political campaigns: A meta-analytic reassessment. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 1176–1209.

LeBas, A. (2010). Ethnicity and the willingness to sanction violent politicians: Evidence from Kenya.

Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1963). Constituency influence in congress. American Political Science Review, 57(1), 45–56.

Mueller, S. D. (2008). The political economy of Kenya’s crisis. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 185–210.

Mueller, S. D. (2011). Dying to win: Elections, political violence, and institutional decay in Kenya. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 29(1), 99–117.

Mutahi, P., & Ruteere, M. (2019). Violence, security and the policing of Kenya’s 2017 elections. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 13(2), 253–271.

Mutiga, M. (2017). Violence, Land, and the Upcoming Vote in Kenya’s Laikipia Region. Crisis Group.

Ortoleva, P., & Snowberg, E. (2015). Overconfidence in political behavior. American Economic Review, 105(2), 504–535.

Petersen, R. B. (2002). An emotion-based approach to ethnic conflict. In Understanding ethnic violence: Fear, hatred, and resentment in twentieth-century Eastern Europe, chapter 2. Cambridge University Press.

Rabushka, A., & Shepsle, K. A. (1972). Politics in plural societies: A theory of democratic instability. Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company.

Rosenfeld, B., Imai, K., & Shapiro, J. N. (2016). An empirical validation study of popular survey methodologies for sensitive questions. American Journal of Political Science, 60(3), 783–802.

Sheffer, L., Loewen, P. J., Soroka, S., Walgrave, S., & Sheafer, T. (2018). Nonrepresentative representatives: An experimental study of the decision making of elected politicians. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 302–321.

Sives, A. (2010). Elections, violence and the democratic process in Jamaica: 1944–2007. Ian Randle Publishers.

Staniland, P. (2014). Violence and democracy. Comparative Politics, 47(1), 99–118.

Travaglianti, M. (2014). Coercing the co-ethnic vote: Violence against co-ethnics in Burundi’s 2010 Elections.

Treisman, D. (2020). Democracy by mistake: How the errors of autocrats trigger transitions to freer government. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 792–810.

Vaishnav, M. (2017). When crime pays: Money and muscle in Indian politics. Yale University Press.

Waki Commission. (2008). Waki report. Commission of Inquiry on Post Election Violence.

Wilkinson, S. I. (2004). Votes and violence: Electoral competition and ethnic riots in India. Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, I. (2010). The rise and fall of political gangsters in Indonesian Democracy. In E. Aspinall & M. Mietzner (Eds.), Problems of democratization in Indonesia: Elections, institutions and society. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Thank you to Thad Dunning, Kate Baldwin, Sue Stokes, and Steven Wilkinson for advice and support over the course of this project, and to Gareth Nellis for comments on an earlier draft. I also benefited from helpful conversations with Jeremy Horowitz, Kathleen Klaus, Eric Kramon, and Adrienne LeBas. Workshop and conference participants at WGAPE, CAPERS, UC Berkeley, and Yale provided very useful feedback. I also wish to thank James Mwangi, Christine Auguste, Anthony Kigera, Joshua Kubutha, Elyvalet Yegon, Carolyne Ngenyura, Sam Ouma, Denish Owiti, Moses Nyabola, Nicholas Otieno Moi, Daniel Saidimu, Alex Kosen, Stanley Nkoitiko, Bob Turasha, Cecil Abungu, Imani Jaoko, and Amina Mohamed for excellent research assistance. The Yale’s MacMillan Center and a Boston University faculty start-up grant provided support for this study. All errors and omissions are my own.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenzweig, S.C. Dangerous Disconnect: Voter Backlash, Elite Misperception, and the Costs of Violence as an Electoral Tactic. Polit Behav 43, 1731–1754 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09707-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09707-9