Abstract

How does female out-migration reconfigure gender values surrounding son preference in origin communities? We propose that the feminization of migration has the potential to infuse origin communities with economic and ideational changes that may challenge son preference. Rural China provides an interesting setting, both because its unprecedented labor out-migration has increasingly included women and because of its persistent son preference. Using data from rural China and instrumental variable regressions to adjust for potential endogeneity bias, this study shows that out-migration of women, but not of men, attenuates son preference among those in origin communities. The role of female out-migration transcends families with direct ties to migration and extends to the entire village. However, cultural context and family positions within that context condition the role of female migration: specifically, the preferences of individuals in families and villages embedded in strong patrilineal cultural practices are less likely to be shaped by female out-migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Son preference is much weaker in urban than in rural China (Attané 2009). This difference is explained by factors such as the greater ideational support for gender equality, an increase in women’s earning opportunities, adoption of neo-local residences among married couples, and a better social welfare system in urban areas.

Despite the persistent son preference, research has pointed to recent ideological departures from patriarchal norms (Yan 2003). Within the broader pattern of distorted sex ratios, a small group of young rural couples with one daughter were indifferent about trying again for a son, and there is a gradual shift in obligation for parental care away from sons toward both sons and daughters.

This study emphasizes inter-county and inter-province migration, following previous research in China (Liang and Ma 2004). Intra-county migration often involves limited change in social environment, as many intra-county migrants move to rather similar socioeconomic settings and even to non-urban areas. Another reason for our focus is that information on the year of first out-migration (the cumulative migration measure) is available only for out-of-county migration.

References

Attané, I. (2009). The determinants of discrimination against daughters in China: Evidence from a provincial-level analysis. Population Studies, 63(1), 87–102.

Banister, J (2004). Shortage of girls in China today. Journal of Population Research, 21(1), 19–45.

Chafetz, J. S. (1999). Structure, agency, consciousness and social change in feminist theories: A conundrum. In Scott G. McNall & Gary N. Howe (Eds.), Current perspectives in social theory (pp. 145–164). New York: JAI Press.

Cohen, M. (2005). Kinship, contract, community, and state: Anthropological perspectives on China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Curran, S., & Rivero-Fuentes, E. (2003). Engendering migrant networks: The case of Mexican migration. Demography, 40(2), 289–307.

Curran, S., Shafer, S., Donato, K., & Garip, F. (2006). Mapping gender and migration in sociological scholarship: Is it segregation or integration? International Migration Review, 40(1), 199–223.

Roodman, D. (2009) Estimating fully observed recursive mixed-process models with CMP. Center for global development working paper 168.

Donato, K., Gabaccia, D., Holdaway, J., Manalansan, M., & Pessar, P. (2006). A glass half full? gender in migration Studies. International Migration Review, 40(1), 3–26.

Du, Y., Park, A., & Wang, S. (2005). Migration and rural poverty in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 33(4), 688–709.

Ebenstein, A., & Leung, S. (2010). Son preference and access to social insurance: evidence from China’s rural pension program. Population and Development Review, 36(1), 47–70.

Enarson, E. P., & Morrow, B. (1998). The gendered terrain of disaster: Through women’s eyes. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Fan, C. (2008). China on the move: Migration, the state, and the household. The China Quarterly, 196, 924–956.

Fan, C.C., & Huang, Y. (1998). Waves of rural brides: Female marriage migration in China. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 88(2), 227–251.

Foner, N. (2002). Immigrant women and work in New York City, then and now. In P. G. Min (Ed.), Mass migration to the United States: Classical and contemporary trends (pp. 231–252). Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

Graham, M., Larsen, U., & Xiping, X. (1998). Son preference in Anhui Province, China. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24(2), 72–77.

Grasmuck, S., & Pessar, P. (1991). Between two islands dominican international migration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gupta, M., Jiang, Z., Li, B., Zhenming, X., Chung, W., & Hwa-Ok, B. (2003). Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? The Journal of Development Studies, 40(2), 153–187.

Halliday, T. (2006). Migration, risk, and liquidity constraints. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54, 893–925.

Hesketh, T., Li, L., & Xing, Z. W. (2005). The effect of China’s one-child family policy after 25 years. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(11), 1171–1176.

Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (1994). Gendered transitions: Mexican experiences of immigration. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Inglehart, R. (1989). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

IOM (International Organization for Migration). (2010). World migration report. Geneva: International Organisation for Migration.

Jacka, T. (2005). Rural women in urban China gender, migration, and social change. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Kanaiaupuni, S. (2000). Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 78(4), 1311–1347.

Kibria, N. (1990). Power, patriarchy, and gender conflict in the Vietnamese immigrant community. Gender and Society, 4(1), 9–24.

Levitt, P. (1998). Social remittances: Migration driven local-level forms of cultural diffusion. International Migration Review, 32(4), 926–948.

Levitt, P., & Lamba-Nieves, D. (2011). Social remittances revisited. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(1), 1–22.

Li, J., & Lavely, W. (2003). Village context, women’s status, and son preference among rural Chinese women. Rural Sociology, 68(1), 87–106.

Liang, Z., & Ma, Z. (2004). China’s floating population: New evidence from the 2000 census. Population and Development Review, 30(3), 467–488.

Lindstrom, D., & Muñoz-Franco, E. (2005). Migration and the diffusion of modern contraceptive knowledge and use in rural Guatemala. Studies in Family Planning, 36(4), 277–288.

Miller, B. D. (1981). The endangered sex: Neglect of female children in rural North India. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Ming, J., & Zhang, J. (2011). Return intentions, migration costs, and remittances. South China Population, 26, 48–56.

Mishra, A., & Goodwin, B. (1997). Farm income variability and the supply of off-farm labor. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79(3), 880–887.

Montgomery, M., & Casterline, J. (1996). Social learning, social influence, and new models of fertility. Population and Development Review, 22, 151–175.

Murphy, R. (2002). How migrant labor is changing rural China (Cambridge modern China series.). Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, R., Tao, R., & Xi, L. (2011). Son preference in rural China: patrilineal families and socioeconomic change. Population and Development Review, 37(4), 665–690.

National Bureau of Statistics. (2011a). China Statistics yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

NBS (National Bureau of Statistics). (2011b). Demographic Statistics from the 2010 Census. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

Parish, W., & Whyte, M. (1978). Village and family in contemporary China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Parrado, E., & Flippen, C. (2005). Migration and gender among Mexican women. American Sociological Review, 70(4), 606–632.

Pedraza, S. (1991). Women and migration: The social consequences of gender. Annual Review of Sociology, 17, 303–325.

Peek, C. W., Lowe, G. D., & Susan Williams, L. (1991). Gender and god’s word: Another look at religious fundamentalism and sexism. Social Forces, 69(4), 1205–1221.

Pessar, P., & Mahler, S. (2003). Transnational migration: Bringing gender in. International Migration Review, 37(3), 812–846.

Portes, A. (2010). Migration and social change: Some conceptual reflections. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(10), 1537–1563.

Poston, D. (2002). Son preference and fertility in China. Journal of Biosocial Science, 34(3), 333–347.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using stata (3rd ed.). College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Roberts, K., Connelly, R., & Xie, Z. (2004). Patterns of temporary labor migration of rural women from Anhui and Sichuan. The China Journal, 52, 49–70.

Santos, G. (2006). The anthropology of Chinese kinship. A critical overview. European Journal of East Asian Studies, 5(2), 275–333.

Solinger, D. (1999). Contesting citizenship in urban China: Peasant migrants, the state, and the logic of the market. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Song, S., & Burgard, S. A. (2008). Does son preference influence children’s growth in height? A comparative study of Chinese and filipino children. Population Studies, 62(3), 305–320.

Stacey, J. (1983). Patriarchy and socialist revolution in China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Taylor, E. J. (1999). The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration, 37(1), 63–88.

Wang, G. (2007). The risk management system of natural disaster in agriculture. Social Science Research, 4, 27–31.

Yan, Y. (2003). Private life under socialism: Love, intimacy, and family change in a Chinese village, 1949–1999. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Zeng, Y., Ping, T., Baochang, G., Yi, X., Li, B., & Li, Y. (1993). Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratio at birth in China. Population and Development Review, 19(2), 283–302.

Zhang, H. (2007). China’s new rural daughters coming of age: Downsizing the family and firing up cash earning power in the new economy. Signs, 32(3), 671–698.

Zheng, Z., Zhou, Y., Zheng, L., Yang, Y., Zhao, D., Lou, C., & Zhao, S. (2001). Sexual behaviour and contraceptive use among unmarried, young women migrant workers in five cities in China. Reproductive Health Matters, 9(17), 118–127.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge generous financial support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the Research Funds of Renmin University of China for our fieldwork.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Sampling Strategy

This national survey was carried out by China Academy of Science, Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy (CAS-CCAP). In selecting the sample, the country was divided into six commonly recognized geographical regions (State Council Development Research Centre 2002). One province was randomly chosen from each region, resulting in six provinces: Shaanxi (Northwest), Sichuan (Southwest), Hebei (Central North), Jilin (Northeast), Jiangsu (East/Central Coast), and Fujian (Southeast). All counties in each province were then sorted into five strata (quintiles) according to their per capita gross value of industrial output. One county was randomly selected from each stratum, yielding a total of 30 counties. All townships in each county were sorted into two groups according to per capita net income—one with per capita net income above the median and the other below the median. One township was randomly selected from each group (60 townships). Following the same procedure for selecting townships, two villages were chosen from each township, yielding a total of 120 villages. For each village, a random sample of 20 households, based on the village household registration list, was sought to complete the interview. In each household, one adult was randomly selected for a face-to-face interview. Because of disruptions caused by the massive Sichuan earthquake in 2008, three villages were dropped from the sample, resulting in a total of 117 villages. About 5 % of the sample was deleted due to missing information on any of the variables used in the analysis, yielding a final sample of 2196.

Appendix 2: Analyses of Remittance Behavior and Son Preference Using Supplementary Data on Migrants

We first examine the remittance behavior of migrants using supplementary data on migrants in China. The migrant data are from the 2009 Twelve-city Migrant Survey. They were collected at about the same time and used standardized survey methods and questionnaires that were similar to the rural data. The survey was conducted in 12 cities across four major urbanized regions: the Yangtze River Delta (Jiangsu and Zhejiang Province), the Pearl River Delta (Guangdong province), Chengdu–Chongqing region (Sichuan Province and Chongqing Municipality), and Bohai Bay Area (Hebei and Shandong Province). In each of the four urbanized regions, one megalopolis (with an urban population of more than 2 million), one large city (500,000–2 million), and one small-medium-sized city (<500,000) were randomly selected. Due to the huge number of migrants in the megalopolis, only one urban district was sampled. In the large and small-medium-sized cities all urban districts in the city were targeted. Then 200 migrants were randomly selected in each city from the migrant registration list provided by the local Public Security Bureau or by the local government migrant administrative agency. The survey resulted in 2398 migrants.

Results are displayed in Fig. 2 in “(Appendix 2: Analyses of Remittance Behavior and Son Preference Using Supplementary Data on Migrants section)”. Among unmarried migrants, women remit at a significantly higher rate to their parents than do men (67 vs. 60 %), net of a range of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Among married migrants, the rate increases for men and decreases for women, but the gender difference is small and insignificant. These findings show the enduring commitment of many migrant daughters to their natal families. Although many migrant women face precarious work and living conditions in destinations and family life-cycle changes such as marriage may slightly alter migrant women’s remittance patterns, they continue to remit their hard earned income to origin families.

Predicted probability of sending remittances to own parents in the past year among Chinese migrants. Based on logistic regressions controlling for age, education, years since migration, whether the respondent has children left behind, number of provinces the migrant has been to, whether currently within-province migration, whether self employed, per capita family income at destination, current place of residence. This analysis was restricted to rural-origin migrants. The gender difference for unmarried migrants is significant at 0.05 level (indicated by *). The gender difference for married migrants is insignificant

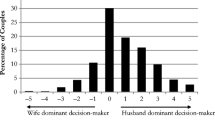

We also compare the degree of son preference between migrants and rural residents, and between female and male migrants. As shown in Fig. 3 in “(Appendix 2: Analyses of Remittance Behavior and Son Preference Using Supplementary Data on Migrants section)”, values surrounding son preference are weaker for urbanward migrants than for rural residents. Specifically, when asked to what degree the respondent feels that it is necessary to have at least one son, over 60 % of rural residents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, compared to less than 45 % of rural-to-urban migrants. In addition, female migrants tend to hold more egalitarian attitudes toward having a son than male migrants. We also examine changes in attitudes by duration of migration and find that the longer migrants stay in destination, the more gender egalitarian views they hold (β = −0.011, s.e. = 0.004, p = 0.003).

Attitudes toward son preference by migration status, and among migrants by gender. Son preference is measured by agreement or disagreement with the statement: “I think that it is necessary to have at least one son.” Chi square test is significant at the 0.001 level for rural-migrant comparison, and significant at the 0.002 level for female-male comparison

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Tao, R. Female Migration, Cultural Context, and Son Preference in Rural China. Popul Res Policy Rev 34, 665–686 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-015-9357-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-015-9357-x