Abstract

We examine information content and related insider trading around private in-house meetings between corporate insiders and investors and analysts. We use a hand-collected dataset of approximately 17,000 private meeting summary reports of Shenzhen Stock Exchange firms over 2012–2014. We find that these private meetings are informative and corporate insiders conducted over one-half of their stock sales (totaling $8.7 billion) around these meetings. Some insiders time their transactions and earn substantial gains by selling (purchasing) relatively more shares before bad (good) news disclosures while postponing selling (purchasing) when good (bad) news is to be disclosed in the meeting. Finally, we conduct a content analysis of published meeting summary reports and find that the tone in these reports is associated with stock market reactions around (1) private meetings themselves, (2) subsequent public release of private meeting details, (3) subsequent earnings announcements and (4) future stock performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Private in-house meetings are held at corporate headquarters with invited investors and sell-side analysts. In-house meetings differ from other management-investor interactions, such as investor conferences (Bushee et al. 2011) and analyst/investor days (Kirk and Markov 2016), in that they are generally not publicized in advance and their content may never become public unless hosting firms are required to disclose meeting details.

While Fair Disclosure Regulation prohibits firms from making selective disclosure of material information, it does not prohibit the selective disclosure of nonmaterial information (Koch et al. 2013).

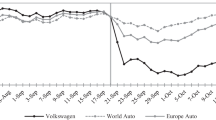

The Shenzhen Stock Exchange is the second-largest stock exchange in China (with the largest being the Shanghai Stock Exchange). According to the World Federation of Exchanges report, as of December 2016, the Shenzhen exchange was ranked as the sixth largest stock exchange in the world with a $3.21 trillion of domestic market capitalization. We translate Chinese RMB into U.S. dollars using exchange rates at the end of each fiscal year.

Research on private in-house meetings has been challenging due to data limitations. Outside of the SZSE, there is no systematic record of private interactions between management and investors and analysts for U.S. firms. Soltes (2014) managed to gather a proprietary dataset of 75 private interactions (mainly private phone calls) for one NYSE company. He found that studies using publicly available data in the United States to study private interactions (such as conference meetings) tends to have significant sample selection bias (e.g., Subasi 2014; Bushee et al. 2017; Green et al. 2014; Kirk and Markov 2016; Bushee et al. 2016). Furthermore, outside of the SZSE, there is no documentation of meeting content. Thus, we know little about what was discussed or who participated in these private meetings (Cheng et al. 2017).

In China, it is only unlawful to carry out insider trading based on material nonpublic information. However, given low litigation risk in China and an imprecise definition of material information, insiders may rely on both types of foreknowledge to inform their trading. While it is difficult to provide direct evidence that insiders trade on material nonpublic information, it remains a possible explanation for our findings.

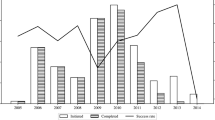

Beginning July 2012, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange required all listed firms to electronically publish a standard meeting report for each in-house meeting through its web portal, “Hu Dong Yi,” at http://irm.cninfo.com.cn/szse/. All reports are written in Chinese and are uploaded in either Microsoft Word or PDF format. We manually collect and code information from these reports.

The SZSE classifies investor relations activities into eight categories: in-house investor meeting, site visit, media interview, public news meeting, analyst conference meeting, performance announcement meeting, road show, and other. To be consistent with the literature on private in-house meetings (Soltes 2014; Solomon and Soltes 2015; Cheng et al. 2016), we focus on the largest two categories (in-house investor meetings and site visits). These two activities account for more than 90% of the total public relations activities reported by SZSE-listed firms. After reading the meeting summary reports, we observe that firms use these two meeting categories interchangeably to describe in-house meetings that host investors and analysts. Accordingly, we combine these two activities and use the general term, private in-house meetings.

CAR is summation of daily abnormal returns (ARs). We use market model to estimate ARs. In our main analyses, we report CAR for the window of (-1, +1). We also calculate CAR for multiple alternative event windows, including (-2, +2), (-5, +5). The conclusions are the same.

The China Securities Regulatory Commission Regulation No. 56 (2007) requires all top executives, directors, and their direct family members (such as parents, spouses, children, or siblings) and beneficial owners who hold more than 5% of the company stock to report sales or purchases of the company’s securities to the company and the stock exchange within two trading days after the transaction. The original disclosed insider trading information can be found in the SZSE website. The Tonghuashun database is developed by Hithink Royal Flush Information Network Co. Ltd. (Ticker 300033), which is listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

We exclude meetings with confounding events, such as earning announcements, merger and acquisition announcements, and press releases.

We also conduct a robustness check by only examining private meetings that do not have other in-house meetings hosted by the same firm in the past 40 days. Our results remain qualitatively similar.

Consistent with the work of Cheng et al. (2017), we find that the number of outside participants and the presence of investment funds in the meeting have highly significant and positive associations with meeting informativeness. In addition, we find that analyst coverage and information quality ranking have negative and significant correlation with SAB_CAR, which supports the conclusion of Cheng et al. (2017) that market reactions around private in-house meetings are stronger for firms with relatively poor information environments. We also find that private meetings held in the week following an earnings announcement are more informative (i.e., higher SAB_CAR and SAB_turnover) than are meetings more than seven days from an earnings announcement.

We match individual insider’s name (and their company) with disclosed meeting participants’ names (and their company) in the published meeting summary reports. If there is a match, we consider the insider has attended a private in-house meeting. Otherwise, we label the insider as not participating in the meeting.

Rozeff and Zaman (1988) and Lakonishok and Lee (2001) find that insiders tend to be contrarian (i.e., insider buying is greater after low stock returns and lower after high stock returns). We include past stock returns to control for the potential contrarian behavior of insiders. We include market cap because Huddart et al. (2007) find that insiders at large firms tend to buy less stock. Finally, insiders tend to buy more stock in the value category, compared to the growth category (Rozeff and Zaman 1988). We use book value-to-market value of equity to control for value versus growth stocks. Our results are also robust if we include all the firm and meeting specific control variables as outlined in the section 3.2.3. For brevity, we only report the results of the parsimonious model used by Huddart et al. (2007).

We conduct robustness checks by using the longer or shorter time windows, such as (-30, -2) or (-10, -2) as pre-meeting windows and (+2, +10) or (+2, +30) as post-meeting windows. The results remain qualitative similar. We also conduct the analysis on a subset of meetings where the meeting date is at least 40 days apart from prior or subsequent meetings hosted by the same firm (to avoid the overlapped insider trading). Our main conclusions remain the same.

Similar to the Rule 16(b) of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, Article 47 in the 2014 Chinese Securities Law requires insiders to surrender any profit made on sales or purchases that are earned through reversing transactions within six months. This rule makes the 180-day trading day horizon particularly interesting.

We collected Fama-French three factor variables for the Chinese stock market from the Resset database. We regress each firm’s daily stock return on the daily three factor variables in 30, 60, 90, and 180 day windows after each insider trade. We estimate the intercept (alpha) from each regression model. We then use this alpha value to measure abnormal stock returns after each insider trade. For brevity, we only report results based on the alpha in the 180 trading days after each insider trade.

We remove observations where the total compensation is zero in the CSMAR database.

If we use the mean value, the average purchase value is 20,255,000 RMB (about $3,266,950). Thus the financial gain will be more than 10 times than the median value estimate.

If we use the mean value of purchase values, the 1.6% abnormal returns translate into 324,081 RMB values, which is 96% of the total compensation that an average SZSE corporate insider earns per year.

We further examine whether the relationship between insider participation in the meeting and trading profitability is moderated by trading value. Using the method of Ravina and Sapienza (2010), we include an interaction term between trading value and an indicator variable for participating insiders (versus nonparticipating insiders) in the models of Table 6 Panel B. We find that the interaction term is not significant. After controlling for trading value, we find that corporate insiders who participated in private meetings make more profitable share purchases than those insiders who did not participate. This relationship does not vary by different levels of trading value.

Most expressions in the Chinese language are only meaningful by combining individual Chinese characters into “phrases” (i.e., at least two Chinese characters combined together to make a phrase in Chinese). Because not all characters have meaning in isolation, we focus on Chinese phrases, which can be more meaningfully and accurately translated into English words.

Frequently mentioned phrases must appear in at least 10 meeting summary reports in our sample.

The question and answer summary is compiled by management and is therefore subject to management’s discretion about what to include.

http://ictclas.nlpir.org/ The textual analysis program is accessed from the Institute of Computing Technology, Chinese Lexical Analysis System and was developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The questions reported in the meeting summary reports are usually short and tend to summarize key points raised by meeting participants. In the textual analysis, we separate questions from answers, and we find that the tone information embedded in answers are more useful to detect positive or negative signals revealed during private meetings. Our textual analysis using only “questions” does not reveal significant findings.

References

Bushee, B., Jung, M., & Miller, G. (2011). Conference presentations and the disclosure milieu. Journal of Accounting Research, 49, 1163–1192.

Bushee, B., Jung, M., & Miller, G. (2017). Do investors benefit from selective access to management? Journal of Financial Reporting, In-Press. Available at https://doi.org/10.2308/jfir-51776.

Bushee, B., Gerakos, J., & Lee, L. F. (2016). Corporate jets and private meetings with investors. Working Paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2141878.

Cheng, Q., Du, F., Wang, X., & Wang, Y. (2017). Do corporate site visits impact stock prices? Singapore Management University School of Accountancy Research Paper No. 2014-12. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2308486.

Cheng, Q., Du, F., Wang, X., & Wang, Y. (2016). Seeing is believing: analysts’ corporate site visits. Review of Accounting Studies, 21, 1245–1286.

China Securities Regulatory Commission Regulation No. 56 (2007). Regulation of insider trading and ownership change of board directors and top executives of listed firms. http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/shenzhen/ztzl/ssgsjgxx/jgfg/sszl/201506/t20150612_278992.htm. Accessed 12 Dec 2017.

Chinese Securities Law. (1999). http://www.sac.net.cn/flgz/flfg/201501/t20150107_115050.html. Accessed 19 May 2017.

Cready, W. M., & Hurtt, D. N. (2002). Assessing investor response to information events using return and volume metrics. The Accounting Review, 77, 891–909.

Duan, L. (2009). The ongoing battle against insider trading: a comparison of Chinese and U.S. law and comments on how China should improve its insider trading law enforcement regime. Duquesne Business Law Journal, 12, 129–161.

Green, C. T., Jame, R., Markov, S., & Subasi, M. (2014). Access to management and informativeness of analyst research. Journal of Financial Economics, 114, 239–255.

Huang, H. (2005). The regulation of insider trading in China: A critical review and proposals for reform. Australian Journal of Corporate Law, 17, 281–322.

Huang, H. (2013). The regulation of insider trading in China: Law and enforcement. In S. M. Bainbridge (Ed.), Research Handbook on Insider Trading (pp. 303–326). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd..

Huddart, S., Ke, B., & Shi, C. (2007). Jeopardy, non-public information, and insider trading around SEC 10-K and 10-Q filings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43, 3–36.

Kirk, M., & Markov, S. (2016). Come on over: Analyst/investor days as a disclosure medium. The Accounting Review, 91, 1725–1750.

Koch, A. S., Lefanowicz, C. E., & Robinson, J. R. (2013). Regulation FD: A Review and Synthesis of the Academic Literature. Accounting Horizons, 27, 619–646.

Lakonishok, J., & Lee, I. (2001). Are insider trades informative? Review of Financial Studies, 14, 79–11.

Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2011). When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. Journal of Finance, 66, 35–65.

Luo, Y. (2005). Do insiders learn from outsiders? Evidence from mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Finance, 60, 1951–1982.

Ng, S., & Troianovski, A. (2015). How some investors get special access to companies? The Wall Street Journal, September 27, 2015. Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-some-investors-get-specialaccess-to-companies-1443407097. Accessed December 12, 2017.

Piotroski, J. D., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. (2016). Political bias of corporate news: Role of conglomeration reform in China. Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 15-52.

Ravina, E., & Sapienza, P. (2010). What do independent directors know? Evidence from their trading. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 962–1003.

Rozeff, M. S., & Zaman, M. A. (1988). Market efficiency and insider trading: new evidence. Journal of business, 61, 25–44.

Solomon, D., & Soltes, E. F. (2015). What are we meeting for? The consequences of private meetings with investors. Journal of Law and Economics, 58, 325–355.

Soltes, E. F. (2014). Private interaction between firm management and sell-side analysts. Journal of Accounting Research, 52, 245–272.

Subasi, M. (2014). Investor conferences and institutional trading in takeover targets. Working paper, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1977518.

SZSE Report. (2006). Fair information disclosure guidelines for SZSE listed firms. http://www.szse.cn/main/disclosure/bsgg/200608109088.shtml. Accessed 15 Jan 2016.

SZSE. (2012). No.2 memorandum for information disclosure for mid and small-size listed companies: investor relations management and information disclosure. Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

Tong, W., Zhang, S., & Zhu, Y. (2013). Trading on inside information: evidence from the share-structure reform in China. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37, 1422–1436.

Zuo, L. (2016). The informational feedback effect of stock prices on management forecasts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 61, 391–413.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the helpful comments of an anonymous referee, Barbara Bliss, Nicole Cade, Shanqing Dong, Jane (Kennedy) Jollineau, Michel Lebas, Shiguang Liao, Jinguo Liu, Dawn Matsumoto, Chris Parsons, Johan Perols, Scott Richardson, Terry Shevlin, Qian Sun, Ruixiang Wang, Mitch Warachka, Carsten Zimmerman, postdoctoral research fellows at the Shanghai Stock Exchange, and workshop participants at the University of San Diego. An earlier version of the paper won the Emerald Best Paper Award at the 2016 China Finance Review International Conference in Shanghai and won the CFA Institute Asia-Pacific Capital Markets Research Award at the 2016 Auckland Finance Meeting in New Zealand. The research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC research grant number: 71672059).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bowen, R.M., Dutta, S., Tang, S. et al. Inside the “black box” of private in-house meetings. Rev Account Stud 23, 487–527 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9433-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9433-z