Abstract

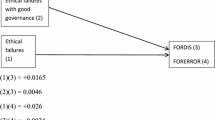

The main purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of internal control material weaknesses (ICMW hereafter) on sell side analysts. We find that ICMW reporting firms have less accurate analyst forecasts relative to non-reporting firms when the reported ICMWs belong to the Pervasive type. ICMW reporting firms have more optimistically biased analyst forecasts compared than non-reporting firms. The optimistic bias exists only in the forecasts issued by the analysts affiliated with less-highly-reputable brokerage houses. The differences in accuracy and bias between ICMW and non-ICMW firms disappear when ICMW disclosing firms stop disclosing ICMWs. Collectively, our results suggest that the weaknesses in internal control increases forecasting errors and upward bias for financial analysts. However, a good brokerage reputation can curb the optimistic bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Key points of Section 302 include: (1) The signing officers must certify that they are responsible for establishing and maintaining internal control and have designed such internal controls to ensure that material information relating to the registrants and its consolidated subsidiaries is made known to such officers by others within those entities, particularly during the period in which the periodic reports are being prepared. (2) The officers must “have evaluated the effectiveness of the registrant’ internal controls as of a date within 90 days prior to the report and have presented in the report their conclusions about the effectiveness of their internal controls based on their evaluation as of that date.

Key points of Section 404 include: (1) Management is required to produce an internal control report as part of each annual Exchange Act report. (2) The report must affirm the responsibility of management for establishing and maintaining an adequate internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting. (3) The report must also contain an assessment, as of the end of the most recent fiscal year of the registrant, of the effectiveness of the internal control structure and procedures of the issuer for financial reporting. (4) External auditors are required to issue an opinion on whether effective internal control over financial reporting was maintained in all material respects by management. This is in addition to the financial statement opinion regarding the accuracy of the financial statements.

For example, Donald J. Peters, a portfolio manager at T. Rowe Price Group, says: "The accounting reforms [of SOX] have been a win. It is [now] much easier for financial statement users to have a view of the true economics" of a company (Wall Street Journal, January 29th, 2007).

A recent working paper by Kim et al. (2009) confirms our results. They find that internal control quality is inversely associated with analysts’ error and forecast dispersion.

For example, Dyntek Inc. disclosed the following deficiencies in their 2004, 10-K: The material weaknesses that we have identified relate to the fact that our overall financial reporting structure and current staffing levels are not sufficient to support the complexity of our financial reporting requirements. We have experienced employee turnover in our accounting department including the position of Chief Financial Officer. As a result, we have experienced difficulty with respect to our ability to record, process and summarize all of the information that we need to close our books and records on a timely basis and deliver our reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission within the time frames required under the Commission's rules.”

For example, Westmoreland Coal Inc. disclosed the following deficiencies in their 2005, 10-K: “The company’s policies and procedures regarding coal sales contracts with its customers did not provide for a sufficiently detailed, periodic management review of the accounting for payments received. This material weakness resulted in a material overstatement of coal revenues and an overstatement of amortization of capitalized asset retirement costs”. Moody’s suggests that these types of material weaknesses are “auditable,” and thus do not represent as serious a concern regarding the reliability of the financial statements.

The detailed classification of Pervasive and Contained ICMWs is provided in “Appendix 1”.

The conclusions of this paper remain the same if we classify G2 firms as firms disclosing only Pervasive ICMWs.

Our sample period starts after the introduction of Regulation Fair Disclosure (Reg. FD). The goal of Reg. FD is to prohibit management from selectively disclosing private information to analysts. However, as pointed out by recent research (see for example, Ke and Yu 2006; Kanagaretnam et al. 2004), there is no empirical evidence of management relations incentive weakening after Reg. FD. In the post-Reg. FD period, there are other incentives for analysts to please management, such as to gain favored participation in conference calls (Libby et al. 2008; Mayew 2008). Anecdotal evidence also shows that Reg. FD does not prevent a company from more subtle forms of retaliations against analysts who issue negative research reports (Solomon and Frank 2003).

Note that our hypothesis is still valid if the forecasts have been made before the disclosure of ICMWs. Doyle et al. (2007a) argue that Sarbanes–Oxley has led to the disclosure of ICMWs that might have existed for some time. Indeed, they find that accrual quality has been lower for ICMW firms relative to non-ICMW firms even in the periods prior to the disclosure of ICMWs.

Brown et al. (2009) document stock market responds to an analyst’s recommendation change and the difference between the analyst’s recommendation and the consensus recommendation. The market’s reaction is strongly influenced by the analyst’s reputation.

It could be argued that our sample might miss some firms which have ICMWs but choose not to disclose them. However, discovery and disclosure of material weaknesses are mandatory according to 2004 SEC FAQ #11. We, therefore, use the disclosure of ICMW as a proxy for the existence of ICMW.

We thank Sarah McVay for making the data available on her website (http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~smcvay/research/Index.html).

If a firm in our final sample reports internal material weaknesses in multiple years, the firm will show up in our sample multiple times. We have 599 distinct firms showing up once in our final sample and 64 firms showing up twice in our sample. The conclusions of this paper remain the same if we exclude these 64 firms from our analyses.

Note that the ACCURACY is defined so that larger errors correspond to a lower level of accuracy.

As a sensitivity test, we calculate ACCURACY and BIAS using the simple average of the measures across the 6 or 12 monthly reporting periods on the IBES before the company’s fiscal year end. In other words, we choose all median forecasts across the six or twelve monthly reporting periods on IBES before the company’s fiscal year end, and then average the median forecasts to create our ACCURACY and BIAS variables. The results are similar to what we report in this paper (not tabulated). When we use forecasts from the prior year instead of the current year, we also get similar results (not tabulated).

Note that the differences in the earnings quality could also be the consequences of the existence of ICMWs. By controlling for absolute abnormal accruals, we may over-control the impact of ICMWs. But it will bias against us finding any results.

Fan and Yeh (2006) find that forecasting error is a negative function of firm size.

The results are similar if we use value-weighted market adjusted cumulative returns.

We thank an anonymous referee for pointing this out to us.

When we use forecasts from the prior year instead of the current year, we also get similar results (not tabulated).

We exclude earnings volatility (EPSVOL) variable because the variable is significantly correlated with SKEW variable. In a sensitivity test, we replace SKEW by EPSVOL, the results are similar to what we report in the paper.

See Shiller (1997) on anchoring behavior of financial analysts.

For firms that disclose ICMWs for multiple years, the last year in which ICMWs are disclosed for the firms in our sample period is used.

References

Ashbaugh-Skaife H, Collins DW, Kinney WR, LaFond R (2008) Internal control deficiencies, remediation and accrual quality. Account Rev 83:217–250

Beneish D, Billings M, Hodder L (2008) Internal control weaknesses and information uncertainty. Account Rev 83:665–704

Bouwman M, Frishkoff P (1995) The relevance of GAAP-based information: a case study exploring some uses and limitations. Account Horiz 9:22–47

Brown LD, Higgins HN (2001) Managing earnings surprises in the U.S. versus 12 other countries. J Account Public Policy 20:371–398

Brown R, Chan H, Ho Y (2009) Analysts’ recommendations: from which signal does the market take its lead? Rev Quant Financ Acc 33:91–111

Chen S, Matsumoto D, Rajgopal S (2006) Is silence golden? An empirical analysis of firms that stop giving quarterly earnings guidance. Working paper, University of Texas at Austin

Cook D (1977) Detection of influential observations in linear regression. Technometrics 19:15–18

Das S, Levine CB, Sivaramakrishnan K (1998) Earnings predictability and bias in analysts’ earnings forecasts. Account Rev 73:277–294

Dechow PM, Sloan RG (1997) Returns to contrarian investment: tests of the naïve expectations hypotheses. J Financ Econ 43:3–28

Doyle J, Ge W, McVay S (2007a) Accruals quality and internal control over financial reporting. Account Rev 82:1141–1170

Doyle J, Ge W, McVay S (2007b) Determinants of weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting and the implications for earnings quality. J Account Econ 44:193–223

Duru A, Reeb D (2002) International diversification and analysts’ forecast accuracy and bias. Account Rev 77:415–433

Eames M, Glover S (2003) Earnings predictability and the direction of analysts’ earnings forecast errors. Account Rev 78:707–724

Fama E, French K (1997) Industry costs of equity. J Financ Econ 43:153–194

Fan D, Yeh J (2006) Analyst earnings forecasts for publicly traded insurance companies. Rev Quant Finance Account 26:105–136

Feng M, Li C, McVay S (2009) Internal control and management guidance. J Account Econ 48:190–209

Francis J, Nanda D, Wang X (2006) Re-examining the effects of regulation fair disclosure using foreign listed firms to control for concurrent shocks. J Account Econ 41:271–292

Ge W, McVay S (2005) On the disclosure of material weaknesses in internal control after the Sarbanes-Oxley act. Account Horiz 19:137–158

Ghosh A, Lubberink M (2006) Timeliness and mandated disclosures on internal controls under section 404. Working Paper, City University of New York

Gu Z, Wu J (2003) Earnings skewness and analyst forecast bias. J Account Econ 35:5–29

Ho J (2004) Analysts’ forecasts of Taiwanese firms’ earnings: some empirical evidence. Rev Pacific Basin Finan Markets Policies 7:571–597

Huang H, Willis R, Zang A (2005) Bold security analysts’ earnings forecasts and managers’ information flow. Working Paper, Duke University

Kanagaretnam K, Lobo G, Mathieu A (2004) CEO compensation mix and analysts forecast accuracy and bias. Working Paper, McMaster University

Ke B, Yu Y (2006) The effect of issuing biased earnings forecasts on Analysts’ access to management and survival. J Account Res 44:965–1000

Kim JB, Song BY, Zhang L (2009) Internal control quality and analyst forecast behavior: evidence from SOX Section 404 disclosures. Working Paper, City University of Hong Kong

Kross W, Ro BT, Schroeder D (1990) Earnings expectations: the analysts’ information advantage. Account Rev 65:461–476

Lang MH, Lundholm RJ (1996) Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. Account Rev 71(4):467–492

Larcker DF, Richardson SA, Tuna AI (2007) Corporate governance, accounting outcomes, and organizational performance. Account Rev 82:963–1008

Libby R, Hunton J, Tan H, Seybert N (2008) Relationship incentives and the optimistic/pessimistic pattern in analysts’ forecasts. J Account Res 46:173–198

Lim T (2001) Rationality and analysts’ forecast bias. J Finance 56:369–385

Lys T, Soo L (1995) Analysts’ forecast precision as a response to competition. J Account Audit Finance 10:751–765

Mayew W (2008) Evidence of management discrimination among analysts during earnings conference calls. J Account Res 46:627–659

Previts G, Bricker R (1994) A content analysis of sell-side financial analyst company reports. Account Horiz 8:55–70

Richardson S, Teoh S, Wysocki P (2004) The walkdown to beatable analyst forecasts: the role of equity issuance and insider trading incentives. Contemp Account Res 21:885–924

Rogers R, Grant J (1997) Content analysis of information cited in reports of sell-side financial analysts. J Finan State Anal 3:17–30

Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) Public Law 107–204, 107th Cong., 2nd Session. GPO, Washington, DC

Schipper K (1991) Commentary on analysts’ forecasts. Account Horiz 5:105–121

Shiller RJ (1997): Human behavior and the efficiency of the financial system. Working Paper. Yale University

Solomon D (2005) Accounting rule exposes problems but draws complaints about cost. Wall Street Journal, May 2, p A.1

Solomon D, Frank R (2003) Stock analysis: `You don’t like our stock? You are off the list’—SEC sets new front on conflicts by taking aim at companies that retaliate against analysts. Wall Street Journal, Jun 19, p C.1

Song M, Lobo G, Stanford M (2006) Accruals quality and analyst coverage, Working paper, University of Idaho

Womack K (1996) Do brokerage analysts’ recommendations have investment value? J Finance 54:137–157

Zhang F (2006) Information uncertainty and analyst forecast behavior. Contemp Account Res 23:1–28

Acknowledgments

Li Xu gratefully acknowledges the financial support from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. Alex P. Tang gratefully acknowledges that this research is supported in part by a summer research grant from the School of Business and Management at the Morgan State University. We appreciate the comments from two anonymous referees and the editor, Cheng-Few Lee. We also appreciate the research assistance of Jui-Chin Chang. All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Material weakness classification examples

1.1 G1: Contained material weaknesses

-

1.

Account-specific

E.g., “U.S. Cellular did not maintain effective controls over the completeness, accuracy, presentation and disclosure of its accounting for income taxes.”(U.S. Cellular Inc., 2004 10-K report)

-

2.

Period-end reporting/accounting policies

E.g., “–a lack of an ongoing formal self-assessment process related to internal control over financial reporting.” (Ivanhoe energy Inc., 2004 10-K report)

-

3.

Revenue recognition

E.g., “The Company’s policies and procedures regarding coal sales contracts with its customers did not provide for a sufficiently detailed, periodic management review of the accounting for payments received. This material weakness resulted in a material overstatement of coal revenues and an overstatement of amortization of capitalized asset retirement costs.” (Westmoreland Coal Co., 2005 10-K report)

-

4.

Account reconciliation

E.g., “The Company did not maintain effective controls over reconciliations of certain financial statement accounts.” (SIRVA Inc., 2004 10-K report)

1.2 G2: Pervasive material weaknesses

-

1.

Segregation of duties

E.g., “Inadequate segregation of duties was noted with respect to the revenue, expenditure and payroll processes as numerous incompatible tasks are performed by the same accounting personnel.” (Versant Co., 2004 10-K report).

-

2.

Subsidiary-specific

E.g., “We have reported to the SEC that one of our foreign subsidiaries operating in Nigeria made improper payments of approximately $2.4 million to an entity owned by a Nigerian national who held himself out as a tax consultant when in fact he was an employee of a local tax authority. The payments were made to obtain favorable tax treatment and clearly violated our Code of Business Conduct and our internal control procedures.” (Halliburton Co., 2002 10-K report)

-

3.

Senior management

E.g., “management did not set a culture that extended the necessary rigor and commitment to internal control over financial reporting.” (SIRVA Inc, 2004 10-K report)

-

4.

Technology issues

E.g., “There are weaknesses in the Company’s information technology (“IT”) controls which makes the Company’s financial data vulnerable to error or fraud; a lack of documentation regarding the roles and responsibilities of the IT function; lack of security management and monitoring and inadequate segregation of duties involving IT functions.” (Earthshell Co., 2005 10-K report)

-

5.

Training and personnel:

E.g., “The Company lacks personnel with adequate expertise in accounting for income taxes in accordance with U.S. GAAP.” (Westmoreland Coal Co., 2005 10-K report)

Appendix 2: Variable definitions

Variables | Definition and data source |

|---|---|

NUMBER NUM | The number of analysts who make the forecasts in calculating the last median earnings Natural logarithm of the number of analysts who make the forecasts in calculating the last median earnings |

SKEW | The skewness of the earnings, calculated as the mean-median difference of price-scaled earnings from the prior five years (minimum of four years) |

SPECIAL | An indicator variable equal to one if special items (Compustat # 17) are not equal to zero, zero otherwise |

RET | Is the equally weighted market adjusted cumulative return over the past three years |

DA | The absolute value of abnormal total accruals. The calculation of DA is estimated using the modified Jones model of Larcker, Richardson and Tuna (2007) |

LOSS | An indicator variable equal to one if earnings are negative, zero otherwise |

ECHG | Is the change in earnings (Compustat #18), calculated as the change in earnings over the previous year scaled by the previous year’s earnings |

NECHG | Is equal to one if ECHG is negative and zero otherwise |

ABSECHG | The absolute change in earnings (Compustat #18), calculated as the absolute value of the change in earnings over the previous year scaled by the previous year’s earnings |

EPSVOL | The standard deviation of earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat #18) estimated using data from the prior 5 years (minimum of 4 years) |

BM | The natural logarithm of book value (Compustat # 60) to the market (Compustat # 25* Compustat #199) of the firms |

ROA | The ratio of return to asset, calculated as earnings before extraordinary items (Compustat #18) scaled by average total assets (Compustat # 6) |

LEV | The ratio of debt (Compustat # 34 + Compustat # 9) to averaged total assets (Compustat # 6) |

MV | Natural logarithm of the market value of equity (Compustat #199*#25) |

FOREIGN | An indicator variable equal to one if foreign currency translation (COMPUSTAT Data Item #150) is not zero, zero otherwise |

G1 | An indicator variable that equals one if a firm discloses only Contained ICMWs in year t, and zero otherwise |

G2 | An indicator variable equal to one if a firm discloses Pervasive ICMWs in year t, and zero otherwise |

ICMW | An indicator variable equal to one if the firm has disclosed internal control material weakness in year t, and zero otherwise |

STALE | The days between the date of fiscal year end and the date of the last annual forecast issued (before the fiscal year end) by an analyst |

ADJSTALE | The median value of the STALE variable for a firm per fiscal year |

AGE | The number of years that a firm has been the CRSP database |

BROKERAGE REPUTATION | The Institutional Investors’ ranking of brokerage houses is used to proxy for brokerage reputation: a brokerage is considered to be of high reputation if it is consistently (at least for three prior years) ranked among the “Leaders” by Institutional Investors during the sample period. The following twelve brokers are identified as highly reputable: Bear, Stearns & Co; CS First Boston; Goldman Sachs; Lehman Brothers; Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette; J.P. Morgan Securities; Merrill Lynch; Morgan Stanley & Co; Paine Webber; Prudential Securities; Salomon Brothers; Smith Barney. The other brokerages are classified as less-highly-reputable |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, L., Tang, A.P. Internal control material weakness, analysts’ accuracy and bias, and brokerage reputation. Rev Quant Finan Acc 39, 27–53 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-011-0243-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-011-0243-2

Keywords

- Internal control material weakness

- Analyst forecast accuracy

- Analyst forecast bias

- Brokerage reputation

- Sarbanes–Oxley Act