Abstract

This paper draws on practice theory to argue that the practiced culture of a society and gender interact to create cultured capacities for social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs. We combine data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) with the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) and World Bank (WB) to identify what cultural practices are most relevant for female entrepreneurs’ practice of social entrepreneurship across 33 countries. Our findings suggest that female entrepreneurs are more likely to engage in social entrepreneurship when cultural practices of power distance, humane orientation, and in-group collectivism are low, and cultural practices of future orientation and uncertainty avoidance are high, when compared to male entrepreneurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

How does culture enable or constrain social entrepreneurial activity? What, if any, is the role of gender in linking culture and social entrepreneurial activity among entrepreneurs? This study applies practice theory to empirically examine how these factors affect entrepreneurs’ cultured capacity towards social entrepreneurship cross-culturally. Practice theory is concerned with the meaningful performance of behavior (Bourdieu 1990). It views culture as a “dynamically stable process of collectively made, reproduced, and unevenly shared knowledge structures that are informational and meaningful, internally embodied, and externally represented and that provide predictability, coordination equilibria, continuity, and meaning in human actions and interactions” (Patterson 2014, p. 1). Similarly, it views gender “as a routine accomplishment embedded in everyday interaction” (West and Zimmerman 1987, p. 125). Hence, we contend that culture and gender are generative schemes that entrepreneurs invoke as tools to inform their actions, which creates a cultured capacity towards social entrepreneurial activity (Swidler 2013).

The practice perspective argues that individuals carry a routinized understanding and knowledge of culture that manifests itself in actual behavior. Culture is a repertoire of tools, or cultured capacities, that an entrepreneur can use at any time to inform their actions (Swidler 1986, 2013). If culture itself is a practice that is habitually and socially situated (Schatzki 2005), it has tangible implications for the practice of social entrepreneurship across societies. Indeed, recent work by Stephan et al. (2015) finds that socially supportive cultural practices are more conducive to social entrepreneurship than performance-based cultural practices.

Furthermore, practice theory argues that social action tends to be an unconscious process of decision-making. This understanding can be particularly important to help explain gender patterns of social action. In fact, some scholars argue that female entrepreneurs are more likely to be social entrepreneurs because it involves caring for others, and such tasks stereotypically tend to fall under feminine domains in many societies (Hechavarría et al. 2017). Yet, recent research finds evidence that people attribute both masculine and feminine characteristics to the practice of social entrepreneurship (Gupta et al. 2019). As a result, we question: to what extent do these assumed blueprints for behavior affect a female entrepreneur’s cultured capacity to practice social entrepreneurship?

To answer these questions, we combine data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) study, and the World Bank (WB), and apply multilevel modeling on a sample of 23,828 entrepreneurs from 33 countries. We test for competing interaction effects of the GLOBE cultural practice measures between genders. Our findings suggest that the relationship between an entrepreneur’s gender and the practice of social entrepreneurship varies across a society’s cultural practices, such that female entrepreneurs are more likely to practice social entrepreneurship in societies that are characterized by low power distance, humane orientation, and in-group collectivism, and high future orientation and uncertainty avoidance.

Our research contributes to discussions on culture and gender in social entrepreneurship by identifying a theoretically grounded multilevel model of social entrepreneurship that links theory and testable reality. Our findings suggest that female and male entrepreneurs develop different behavioral repertoires around entrepreneurship by selectively using culture to inform their social entrepreneurial behavior. Next, our work moves beyond the normative values approach to understanding culture in entrepreneurship. The distinction between values and practices is of relevance because what a society “practices” in terms of behavior does not necessarily align with what it “preaches” in terms of its espoused values (Brewer and Venaik 2010).Footnote 1 Finally, our study uses a methodology that has traditionally been associated with positivism in an adventurous way. We take an informed pluralist approach to scale up research in entrepreneurship that draws on practice theory via nomothetic methods to frame our investigation of social entrepreneurship, gender, and culture. In doing so, we provide a cross-country comparison of social entrepreneurship which informs policymakers, practitioners, and academics on the considerable influence of cultural practices on female entrepreneurs.

2 Culture as a practice: on culture, women, and social entrepreneurship

Practice theory focuses on understanding practices, particularly those “routinized type of behavior[s] which consists of several elements, interconnected to one another: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion and motivational knowledge” (Reckwitz 2002, p. 49). From this viewpoint, culture is a shared understanding of action that people continuously draw upon to make sense of their behaviors (Swidler 1986). How people act in the social world is based on a learned toolkit, or repertoire of specific skills, habits, and practices that they acquire throughout their lives. These repertoires are known as cultured capacities (Swidler 2013), and they capture a culture’s role in enabling (or constraining) an individual’s capacity to act. Cultured capacities are the link between culture and action because action and interaction require a person to deploy a host of culturally specific skills based on a common societal understanding about behavior. Thus, cultured capacities are social actions people are well equipped at, or the arenas of social life they know how to navigate.

With this in mind, entrepreneurs can invoke culture as a tool to advance their cultured capacity around social entrepreneurship. This is because entrepreneurs can use culturally relevant knowledge to construct strategies of action specific to social entrepreneurship. Additionally, identifiable cultural practices affect gendered patterns of social action across societies. Social action itself is gendered because it follows a culturally defined division of labor between the sexes. Globally, women are often caretakers and nurturers for households, and in some cases even whole communities, while in others they are a vital part of the workforce who take the same jobs as men in their societies (De Clercq et al. 2019). Since gender roles vary significantly across cultures, this can influence how female entrepreneurs invoke culture to deploy cultured capacities around social entrepreneurship. Overall, the “doing” of culture and gender creates different cultured capacities for female (and male) entrepreneurs to deploy when they engage in entrepreneurship.Footnote 2 This is because culture and gender provide repertoires of knowledge that structure the kinds of expected responses that entrepreneurs develop from their social interactions.

3 Hypotheses

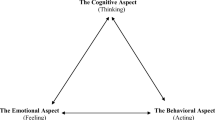

To examine the interplay cultural practices and gender on the deployment of cultured capacities for social entrepreneurship, we draw on the GLOBE study, which is one of the few cross-cultural research protocols that differentiates culture as practices versus culture as values in the conceptualization of cultural dimensions. The GLOBE study assesses nine cultural dimensions for both actual societal practices (“As Is”) and espoused values (“Should Be”) across cultural settings: gender egalitarianism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, future orientation, humane orientation, performance orientation, assertiveness, institutional collectivism, and in-group collectivism (House et al. 2002).Footnote 3 In the following sections, we examine the nine dimensions of national culture using the GLOBE cultural practice measures and articulate how we believe them to be conducive to an entrepreneur’s engagement in social entrepreneurship, particularly for female entrepreneurs (Fig. 1).

3.1 Gender egalitarianism

Gender egalitarianism is “the degree to which a collective minimizes gender inequality” (House et al. 2004, p. 359). Women in high gender egalitarian societies generally adopt non-traditional gender roles, experience less occupational sex segregation, and have more significant decision-making power in professional and community affairs. Conversely, women in low gender egalitarian societies typically embrace the prescribed division of labor between women and men; thus, women hold fewer positions of authority, experience more occupational sex segregation, and have minimal decision-making power in community affairs (House et al. 2004).

Research suggests that women and men tend to have jobs that fit stereotypical gender attributes (Wood and Eagly 2002). Reinforcing this gendered view, entrepreneurship is characterized as a masculine phenomenon, and entrepreneurs are often described as aggressive, bold, calculative risk-takers (Ahl 2006), whereas social entrepreneurship is associated with more feminine characteristics, such as care ethics, compassion, and altruism (Hechavarría et al. 2017).Footnote 4 Research does indeed demonstrate that female entrepreneurs give more priority to social value creation than male entrepreneurs (Brieger et al. 2019). Therefore, cultures with egalitarian gender practices may have higher rates of social entrepreneurship (Canestrino et al. 2020), particularly among female entrepreneurs because these social practices legitimate and do not limit the participation of women in various aspects of society.

-

H1a: Societal-level gender egalitarian cultural practices will be positively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H1b: Societal-level gender egalitarian cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be more likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level gender egalitarian cultural practices are high.

3.2 Uncertainty avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance is “the extent to which a society, organization, or group relies on social norms, rules, and procedures to alleviate the unpredictability of future events” (House et al. 2004, p. 30). In societies where uncertainty and ambiguity are avoided, individuals tend to rely on formal interactions with others, emphasizing formalized policies and procedures, among other actions, to discourage such ambiguity. Furthermore, individuals in these societies are resistant to change, tend to embrace order, and take moderately calculated risks (House et al. 2004). Conversely, societies low in uncertainty avoidance are characterized by the use of informality in interactions with others; individuals are less orderly and keep fewer records, among other characteristic behaviors (Javidan et al. 2006).Footnote 5

Research finds that uncertainty avoidance is positively correlated with the prevalence of business ownership (Wennekers et al. 2007). But, at the individual level, uncertainty avoidance is negatively linked to innovation (Taras et al. 2010). Uncertainty is particularly accentuated in the practice of social entrepreneurship because founders tend to struggle with more risk elements than traditional entrepreneurs (Dees et al. 2002), since they tend to be more innovative (Lepoutre et al. 2013) and novel (Renko 2013). Therefore, entrepreneurs will likely prefer not to engage in social entrepreneurship in those societies that are intolerant of uncertainty. Furthermore, we suggest that female entrepreneurs in countries that prefer structured situations (i.e., are intolerant of uncertainty) will also be less likely to engage in social entrepreneurship because their tendency to be more risk averse than male entrepreneurs (Caliendo et al. 2009). Research finds that the risk-taking propensity of women decreases as uncertainty avoidance increases across countries (Mueller 2004).

-

H2a: Societal-level uncertainty-avoidant cultural practices will be negatively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H2b: Societal-level uncertainty-avoidant cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs are less likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level uncertainty-avoidant cultural practices are high.

3.3 Power distance

Power distance captures whether people in a society expect power to be distributed equally among its members. Societies high in power distance view power as a mechanism to provide social order. Such societies are typified by social classes that differentiate groups and restrict upward social mobility. Resources are available to only a few, and information is localized and hoarded (House et al. 2004). Conversely, countries characterized by low power distance have a large middle class where upward social mobility is common, resources are available to almost all, and information is widely shared. Power is linked to corruption and coercion in low power distance societies.

Research shows that power distance negatively impacts entrepreneurship (Autio et al. 2013). Societies high in power distance view self-employed as an attempt to challenge the status quo. Moreover, the degree of power distance in society can influence how power is concentrated, which affect one’s ability to challenge power structures. Therefore, social initiatives are less likely to be pursued by entrepreneurs if power distance is high, because social entrepreneurship is often portrayed as a challenge to power and hierarchy (Meek et al. 2010).

Power distance can also affect the societal expectations of women and the appropriate roles they can hold. In societies where power is not distributed equally, it is likely that women have fewer economic and political rights than men. This is because women are considered a low power group, holding a secondary position to men across all social locations within a given society (Ross-Smith and Huppatz 2010). Resultantly, we suggest that societies high in power distance will negatively impact the cultured capacity of female social entrepreneurship because it would be increasingly difficult for them to challenge the equilibrium of power in the market, even if they are already entrepreneurs.

-

H3a: Societal-level power distance cultural practices will be negatively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H3b: Societal-level power distance cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be less likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level power distance cultural practices are high.

3.4 Future orientation

Future orientation is the “degree to which a collectivity encourages and rewards future oriented behaviors such as planning and delaying gratification” (House et al. 2004, p. 282). Societies characterized by high future orientation tend to save now for the future, work for long-term success, and believe material success and spiritual fulfillment are integrated (House et al. 2004). Conversely, societies low on future orientation are characterized by a disposition that prefers instant gratification; spending now, rather than saving for the future; and viewing material success and spiritual fulfillment as independent of each other (often requiring trade-offs).

Societies high on future orientation are less likely to discount the future because they do not decouple the future and the present. People in future-oriented societies judge actions by thinking about what would be best in the far future. This has relevant implications for the practice of social entrepreneurship, because an entrepreneur’s vision, mission, and goals influence the way that they interpret market risks and opportunities (DiVito and Bohnsack 2017). In a societal context that encourages behaviors that maximize benefits for future generations, we should therefore see more entrepreneurs practicing social entrepreneurship. Indeed, recent research finds a positive correlation between societal-level future orientation and the societal rate of social entrepreneurial activity (Canestrino et al. 2020).

Women on average score significantly higher than men in terms of general future orientation (Zimbardo and Boyd 2015). This suggests that women, cross-culturally, may be more concerned about the future. Since women have more varied content in their representations of the future, emphasize interpersonal relationships more readily than men do when thinking about their future self (Greene and DeBacker 2004), and practice care and concern for their future and other beings (Hamington and Sander-Staudt 2011), it could be that female entrepreneurs may more alert to opportunities linked to social value creation in future oritented socities.

-

H4a: Societal-level future-oriented cultural practices will be positively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H4b: Societal-level future-oriented cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be more likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level future-oriented cultural practices are high.

3.5 Humane orientation

Humane orientation measures the degree to which individuals practice compassion towards others. Humanistic societies encourage people to be helpful and supportive in the interest of others. In addition to fostering benevolence, humane orientation facilitates a climate of support. Humane orientation also captures aspects of servant leadership. Servant leadership emphasizes service to others, especially fulfillment of followers’ needs, as a critical element to create more human organizations and, in turn, induce the best from followers (Greenleaf 1977). As a result, servant leaders focus less on self and more on humility and the needs of others.

Humane orientation should be linked to the practices of duty and social responsibility associated with social entrepreneurship, rather than practices of self-interest often associated with commercial entrepreneurship. Servant leadership requires one to take a humane approach to thinking and doing. Some of the attributes associated with servant leadership (e.g., humility, service, appreciation, caring and developing of others, creating value for the community) correspond to attributes associated with social entrepreneurship (Russell and Gregory Stone 2002). Consequently, humane orientation should positively influence the practice of social entrepreneurship because the act of venturing to serve others strongly aligns with the servant leadership model.

Also, women are more inclined to help and support others (Gilligan 1988; VanSandt et al. 2006). Work examining women and leadership finds that women generally have a more collaborative and participative nature when compared to men. In fact, women tend to self-identify as servant leaders (Lehrke and Sowden 2017). This suggests that women who take leadership roles as entrepreneurs may be more likely to engage in servant capacity. Since humane orientation draws on servant leadership, and servant leadership is linked to social entrepreneurship, we should expect female entrepreneurs to deploy cultured capacities towards social entrepreneurship in cultures that prescribe humane orientation.

-

H5a: Societal-level humane-oriented cultural practices will be positively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H5b: Societal-level humane-oriented cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be more likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level humane-oriented cultural practices are high.

3.6 Performance orientation

Performance orientation captures the degree to which society rewards excellence and encourages high achievement and innovation. Performance orientation is derived from McClelland’s (1961) work on the need for achievement, “which is assumed to be a non-conscious individual-level motive” (House et al. 2010, p. 121). High performance societies prioritize competitiveness, innovation, and success (Hofstede 2001). People in performance-oriented cultures usually initiate proactive strategies to exploit opportunities that interrelate with the external environment. Therefore, it should be no surprise that there is a positive relationship between commercial entrepreneurial activity and performance orientation (Autio et al. 2013).

Social entrepreneurship is often portrayed as a means to resolve societal challenges in an innovative or better way than existing practices do (Howaldt et al. 2015). Also, social entrepreneurship is typically a more challenging form of venturing activity than commercial entrepreneurship (Santos 2012). Since performance-oriented societies stimulate the need for achievement in people (Zahra et al. 2005), entrepreneurs may also prioritize practicing social entrepreneurship in order to maximize their need to achieve.

Traditionally, women find themselves with different sets of resources and opportunities when compared to men. Yet, research finds that in high performance organizational cultures, women hold more top management positions (Badjo and Dickson 2001). This suggests that in performance-oriented cultures, female entrepreneurs may have better access to the resources needed to create a business because such cultures prioritize training, development, and results. And, research finds that female entrepreneurs are more likely to use external business support, such as advice, others’ opinions, guidance, and coaching, compared to male entrepreneurs (Chell 2013). Since prescriptive practices within performance-oriented cultures support and encourage a can-do attitude, this should help female entrepreneurs actualize their innate social ventures interests (Hechavarría et al. 2017).

-

H6a: Societal-level performance-oriented cultural practices will be positively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H6b: Societal-level performance-oriented cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be more likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level performance-oriented cultural practices are high.

3.7 Assertiveness

Assertiveness captures the degree to which people are self-confident, decisive, and forceful in their relationships with others (House et al. 2004). Cultures that reflect high levels of assertiveness have practices that encourage being strong-willed, ambitious, and confident. Conversely, societies that score low on assertiveness encourage modesty and tenderness, as well as tradition, seniority, and experience (Canestrino et al. 2020). Non-assertive societies foster solidarity, loyalty, and cooperative behavior (House et al. 2004). Research suggests cultural practices of assertiveness encourage individuals to behave in a self-interested manner to succeed, thus contrasting with the inner meaning of social entrepreneurial activity (Parboteeah et al. 2012). Building on this logic, we would expect a negative relationship between assertiveness and a cultured capacity towards social entrepreneurship.

Women tend to exhibit behaviors that reflect compassion and empathy and are often portrayed as communal and nurturing (Dwivedi et al. 2018). On the other hand, men tend to exhibit behaviors that reflect dominance, competitiveness, and assertiveness (Toh and Leonardelli 2012). Women venturing in highly assertive societies thus may perceive the outcome of their socially driven entrepreneurial efforts as less desirable than females in low assertive cultures. Therefore, female entrepreneurs in societies that show practices of strong assertiveness are less likely to enter social entrepreneurship.

-

H7a: Societal-level assertive cultural practices will be negatively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H7b: Societal-level assertive cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be less likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level assertive cultural practices are high.

3.8 Institutional collectivism

Behaviors that promote loyalty and cohesion at the societal level through generalized trust towards peers are linked to the cultural practices of institutional collectivism (House et al. 2004). Countries that exhibit high levels of institutional collectivism encourage and reward the collective distribution of resources and collective action, whereas societies low on institutional collectivism practice individualistic, independent, and self-reliant behavior (Javidan et al. 2006). Research demonstrates that institutional collectivism is detrimental to entering entrepreneurship (Autio et al. 2013). However, it could be the case that among entrepreneurs, institutional collectivism positively influences the choice to practice social entrepreneurship because it is a risk-sharing social behavior benefiting society which focuses on the needs of others or the collective.

Furthermore, societies that practice high institutional collectivism may positively affect female entrepreneurs practicing social entrepreneurship because the descriptive practices of collectivist societies tend to invest more in the redistribution of structural resources. Again, women typically tend to have less access to resources and opportunities when compared to men. If institutional collectivism is high, societal expectations may facilitate women’s participation in social entrepreneurship through structural redistribution of resources to legitimate female entrepreneurs in social entrepreneurship. This is because the prescriptive behavioral practices institutional collectivism aligns with the female gender role stereotype of caring for others (Gilligan 1988).

-

H8a: Societal-level institutional collectivist cultural practices will be positively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H8b: Societal-level institutional collectivist cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be more likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level institutional collectivist cultural practices are high.

3.9 In-group collectivism

The degree to which people express pride, loyalty, and cohesiveness in their families and/or organizations and how much they depend on their families and/or organizations reflects cultural practices of in-group collectivism (House and Javidan 2004). Individuals in societies prioritizing in-group collectivism are characterized by giving high importance to relationships and emotional dependence of their in-group. An in-group is an exclusive group of people with a shared interest or identity (e.g., families, friends, organizations).

In-group collectivist societies focus primarily on the interest and welfare of their in-group, showing less solidarity with the out-group. This can be explained by the existential hardship with which in-group collectivist societies are typically confronted, as they tend to be economically poorer and more vulnerable (Welzel 2013). Under conditions of financial hardship, people focus more on the needs of their in-group (e.g., family). Entrepreneurs should therefore care less for the needs of others in in-group collectivist societies, negatively affecting the prevalence of social entrepreneurship. Yet, the need for social entrepreneurship should be higher in in-group collectivist societies because people tend to be poorer (Triandis 1995). Instead, entrepreneurs will be more commercially oriented, as they can use the profits for the sake of their in-group’s survival.

Furthermore, in-group collectivism may affect female entrepreneurs through the in-group’s beliefs regarding women’s loyalty to family. We assume that it is likely the case that in in-group collectivist cultures, female entrepreneurs will choose commercial entrepreneurial practices because it allows them to use the profits in the interest of their in-group (unlike social entrepreneurial practices, which would address the interests and needs of collective out-group members). Moreover, in-group collectivist cultures are also more traditional, which could also push female entrepreneurs into commercial entrepreneurship to provide for their in-group (Brieger et al. 2019).

-

H9a: Societal-level in-group collectivist cultural practices will be negatively associated with the practice of social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs at the individual level.

-

H9b: Societal-level in-group collectivist cultural practices moderate the relationship between gender and social entrepreneurship, such that female entrepreneurs will be less likely to practice social entrepreneurship when societal-level in-group institutional collectivist cultural practices are high.

4 Methods

4.1 Sample

We pool data from the countries participating in the 2009 and 2015 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey (APS) and combine the aggregate corresponding GLOBE cultural practice measures with World Bank (WB) data as well. The GEM research program constitutes the single largest and most recognized program to systematically research (social) entrepreneurial activity on an international level (Bergmann et al. 2014; Brieger and De Clercq 2019). Our sample includes all respondents that are business owner from both 2009 and 2015 because we are interested in assessing the impact of culture on an entrepreneur venturing in a socially oriented organization. We classify venturing activity either a nascent entrepreneur, baby business owner, or an established business owner.Footnote 6 The sample is weighted according to the adult labor force (ages 18–64) for the respective countries provided by GEM. Detailed descriptions of the methods and sampling frame used to generate the GEM database are reported in Reynolds et al. (2005). Our final sample consists of 23,828 business owners that have complete information on our variables of interest in 33 countries.

4.2 Measures

4.2.1 Dependent variables

In order to test our hypotheses, we use item Q6A1 from the GEM interview schedule and label it social entrepreneurship. The social entrepreneurship variable is binary and indicates whether a respondent is setting up a business or owning–managing a young business or managing an established business that has a social focus (Lepoutre et al. 2013). To be classified as a social entrepreneurial venture, respondents have answered yes to being a social entrepreneur (see Table 1).

4.2.2 Independent variables

One objective of our research is to investigate the impact of culture operationalized via GLOBE’s practice dimensions, to understand how the manifestation of cultural practices within each country directly impacts social entrepreneurial activity.

GLOBE assesses these cultural dimensions encompassing both values (“Should Be”) and actual practices (“As Is”). As a result, GLOBE has two sets of measures for each dimension of interest, “value” measures and “practice” measures (House et al. 2002). Cultural values, or the content of culture, are assessed in response to the same questionnaire items in the form of judgments of “what should be.” This reflects respondents’ desires and aspirations about the way things should be done (Javidan et al. 2005). Therefore, as measured by GLOBE, cultural values represent an individual’s views of how the society (or organization) should behave. In contrast, cultural practices, or the process of culture, are measured with survey items assessing “what is” or “what are” common behaviors and institutional practices in society. Cultural practices capture the way things were currently done in a society. We utilize a society’s aggregate GLOBE practice score for gender egalitarianism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, future orientation, humane orientation, performance orientation, assertiveness, institutional collectivism, and in-group collectivism. If a country score is not available for a GEM country because it was not surveyed in the GLOBE protocol, we drop that country from our analysis.

Finally, Female captures the sex of the respondent, where women are coded one and men as zero.

4.2.3 Control variables

At the individual level, we control for respondent’s age, household income, education, employment status, and personal attributes associated with entrepreneurial perceptions (Brieger and Gielnik 2020). Education is an ordinal variable based on the United Nations seven stages of schooling. Household income is recoded into an ordinal variable to represent the lowest third percentile, middle third percentile, and the highest third percentile of reported household income among respondents. Finally, we control for personal attributes such as having the skills to start up, fear of failure, know an entrepreneur, and see opportunities. All these items are derived from the 2009 and 2015 GEM APS datasets. We also control for contextual socio-economic factors such as GDP per capita (in US dollars), GDP growth (in %), the size of a country’s population, population growth (in %), and unemployment rate (in %). Data were taken from the World Bank Database for each country in our sample for the years 2009 and 2015. Table 1 provides a list of all variables utilized in this study with a brief description and source of the data. We also include a dummy variable to control for 2015 since we pool data from both GEM 2009 and 2015.

4.3 Empirical approach

To test our hypotheses, we conducted multilevel mixed effects logistic regression using the “melogit” command in Stata 15. Multilevel models are specifically geared towards the statistical analysis of data that have a hierarchical structure, such as ours where individuals are nested in countries. Since ignoring the interdependency between data at individual and country levels can lead to artificial significant effects, multilevel modeling considers the nested data structure and simultaneously estimates the variability in the dependent variable within and between countries (Snijders and Bosker 2012).

To check the appropriateness of our multilevel modeling approach, we conducted a likelihood ratio test and compared a random intercept-only model (no predictors) with a one-level, ordinary logistic regression model. The result (χ2(1) = 1162.68, p < = 0.000) shows that the estimated variance component was different from 0, so a random intercept model helps explain critical variance in the dependent variable, even in the absence of the independent variables. First, we estimated the null model to identify the variation in our dependent variable that is associated with inter-individual (differences between respondents in different countries) and intra-individual differences (differences between individuals within countries). An ICC value of 0.139 indicates that approximately 14% of the variance in our dependent variable occurs between countries.Footnote 7

5 Results

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics, and Tables 3 and 4 show the bivariate relationships of the variables used in the analysis. Approximately 11% of the entrepreneurs in our sample are social entrepreneurs. Table 3 shows that social entrepreneurship is significantly positively associated with education, household income, start-up skills, knowing an entrepreneur, seeing opportunities, uncertainty avoidance, and future orientation, and is significantly negatively associated with age, full-/halftime job, fear of failure, power distance, and in-group collectivism. The results of Table 4 show that the country-level variables associated with cultural practices are strongly correlated. To confirm that there were no multicollinearity issues in our subsequent analysis, we completed collinearity diagnostics and calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF). A VIF of 10 or higher is a cause for concern. Within our sample, the mean VIF is 3.09, with a high of 7.64 and a low of 1.03. After reviewing the collinearity diagnostics, we were convinced that there was not a severe collinearity problem and went ahead with the analysis.

Table 5 presents the empirical results of our multilevel mixed effects logistic regressions. Model 1 includes the control variables, and Model 2 adds the cultural practice measures. Models 3 through 12 integrate the interaction terms between the female and cultural practice variables.

The results of Model 1 show that being a female entrepreneur (β = − 0.016, n.s., OR = 0.984) has no significant effect on practicing social entrepreneurship among entrepreneurs. Furthermore, social entrepreneurship is significant and positively associated with education (β = 0.259, p < 0.001, OR = 1.296), start-up skills (β = 0.263, p < 0.001, OR = 1.301), whether an entrepreneur knows an entrepreneur (β = 0.463, p < 0.001, OR = 1.589), and whether an entrepreneur sees opportunities (β = 0.377, p < 0.001, OR = 1.458), at the individual level, and GDP per capita (β = 0.011, p = 0.069, OR = 1.011) at the country level. Conversely, social entrepreneurship is significant and negatively associated with household income (β = − 0.060, p < 0.001, OR = 0.942) and full-/halftime job (β = − 0.200, p < 0.001, OR = 0.819) at the individual level, and GDP growth. (β = − 0.030, p = 0.024, OR = 0.970) and the percent of total national unemployment (β = − 0.037, p = 0.004, OR = 0.966) at the country level.

Model 2 includes the GLOBE cultural practice measures. Model 2’s results now show that population (β = 8.04e−10, p = 0.086, OR = 1) becomes significant, and that gender egalitarianism (β = 0.480, n.s., OR = 1.616), uncertainty avoidance (β = − 0.215, n.s., OR = 0.807), power distance (β = − 0.185, n.s., OR = 0.831), future orientation (β = − 0.148, n.s., OR = 0.862), humane orientation (β = 0.072, n.s., OR = 1.075), performance orientation (β = 0.252, n.s., OR = 1.286), assertiveness (β = − 0.165, n.s., OR = 0.848), institutional collectivism (β = − 0.045, n.s., OR = 0.956), and in-group collectivism (β = 0.366, n.s., OR = 1.442) have no significant effect on practicing social entrepreneurship. When a hypothesized pattern does not show up as a main effect, it still makes sense to look at interactions because p-values are just one piece of information (Gelman and Loken 2014). And since statistical significance is not the same as practical importance (Gelman and Stern 2006), we proceed to examine the interaction effects for gender and the GLOBE cultural practice measures on social entrepreneurship. We suspect the main effects of the aggregate cultural variables are not significant because there is likely a crossover interaction effect at the individual level between male and female entrepreneurs. This is because we theoretically believe the effect of cultural practices is dependent on gender, and in fact we find evidence that this is the case in some our models.

Model 4 shows evidence of a significant crossover interaction effect of uncertainty avoidance (β = 0.146, p = 0.049, OR = 1.157) on social entrepreneurship for female entrepreneurs (β = − 0.622, p = 0.146, OR = 0.537) (see Fig. 2a). Model 5 shows evidence of a significant crossover interaction effect of power distance and female (β = − 0.278, p = 0.038, OR = 0.757) for female entrepreneurs (β = 1.444, p = 0.04, OR = 4.239) on social entrepreneurship (see Fig. 2b). Model 6 shows evidence of a significant crossover interaction effect of future orientation (β = 0.177, p = 0.075, OR = 1.194) for female entrepreneurs (β = − 0.691, p = 0.07, OR = 0.501) on social entrepreneurship (see Fig. 2c). Model 7 shows evidence of a significant crossover interaction effect of humane orientation (β = − 0.238, p = 0.013, OR = 0.788) for female entrepreneurs (β = 0.927, p = 0.016, OR = 2.527) on social entrepreneurship (see Fig. 2d). Model 11 shows evidence of a significant crossover interaction effect of in-group collectivism (β = − 0.207, p < 0.001, OR = 0.813) for female entrepreneurs (β = 1.051, p = 0.001, OR = 2.862) on social entrepreneurship (see Fig. 2e). Table 6 summarizes all of our findings.Footnote 8

6 Discussion

So, what does this study tell us about culture and gender from the practice theory perspective in regard to social entrepreneurship? First, we see empirical evidence that the effect of culture depends on an entrepreneur’s gender. This is likely because culture and gender operate together as a generative scheme to direct how entrepreneurs operate in their social milieu via socially situated action. Indeed, in terms of cultured capacities around social entrepreneurship, we see compelling statistical evidence that gender is one of the tools, or resources, in an entrepreneur’s toolkit when venturing. Resultantly, our work suggests that female and male entrepreneurs develop different behavioral repertoires around social entrepreneurship by selectively using culture to inform their entrepreneurial behavior.

The question we posed in the beginning of the paper is now important to revisit: to what extent do cultural practices affect a female entrepreneur’s cultured capacity to engage in social entrepreneurship? We find that female entrepreneurs are more likely to deploy cultured capacities around social entrepreneurship in uncertainty-avoidant societies when compared to male entrepreneurs. However, cultures that are characterized by uncertainty avoidance have an attenuating effect on practicing social entrepreneurship overall, supporting prior research (Canestrino et al. 2020). Female entrepreneurs are more likely to deploy cultured capacities towards social entrepreneurship in low power distance societies. In high power distance societies, there is an unequal distribution of resources, creating a challenging environment for entrepreneurs of low-power groups (e.g., women, minorities, immigrants). This creates impediments for social entrepreneurs because their startups often create solutions for low-power groups. Female entrepreneurs deploy cultured capacities around social entrepreneurship in future-oriented societies, while simultaneously inhibiting male entrepreneurs’ ability to deploy such cultured capacities. What is striking about this finding is how male entrepreneurs are negatively affected by future-oriented cultural practices. It seems future orientation attenuates the well-established, sex-linked variation in temporal perception for men, whereby men are distinctively future-oriented, and women are present-oriented (Zimbardo and Boyd 2015). Humane orientation decreases female entrepreneur’s deployment of cultured capacities in social entrepreneurship. The attenuating effect of humane orientation on female entrepreneurs is surprising because we argued that humane orientation would encourage women who take entrepreneurial leadership roles to engage in social entrepreneurship due to the innate servant leadership capacities of women. Instead, humane orientation increases the cultured capacity of male entrepreneurs into social entrepreneurship. Maybe this happens because generosity and caring are not only attributed to women (Gilligan 1988) but are universal, prescriptive behaviors. Finally, we find that in-group collectivism has a slightly stronger effect on male entrepreneurs than female entrepreneurs in terms of their cultured capacity towards social entrepreneurship. This may be because social practices prioritizing in-group interests over individual interests are linked to structures and mechanisms that try to create benefits for one’s immediate group (e.g., family, ethnic group, local community). In other words, it could be the case that entrepreneurs are targeting opportunities for their in-groups through social entrepreneurship.

6.1 Contributions

First, our work presents a theoretically grounded multilevel model of social entrepreneurship that links theory and testable reality. A multilevel investigation of entrepreneurship is fundamental to understanding the true nature of this social practice. Multilevel research captures the complex interplay between individuals and situations that individual-level analysis cannot capture (Kozlowski and Klein 2000), thereby better capturing the real-life complexity social entrepreneurship.

Second, our study uses a methodology that has traditionally been associated with positivism. We take an informed pluralist approach to scale up research in entrepreneurship that draws on practice theory via nomothetic methods to frame our investigation of social entrepreneurship, gender, and culture. Because to really understand the practice of social entrepreneurship, more work needs to be done to reflect practices at population levels. Furthermore, our approach allows us to identify general patterns and trends which can be tracked over time in future research as more data is collected around social practices in protocols like GEM and other entrepreneurship panel studies (e.g., Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics). Such insights could be used to bridge knowledge in more detail about the habits, patterns, and routines that comprise the practice of (social) entrepreneurship using large-scale survey work from an explicit practice theory approach.

Finally, an important contribution of this research is our focus on cultural values and not cultural practices. What a society “practices” in terms of behavior does not necessarily align with what it “preaches” in terms of espoused values (Brewer and Venaik 2010), which has important implications for national governments. Policymakers need to understand that their cultural practice configuration may not be suited for encouraging cultured capacities around social entrepreneurship among female entrepreneurs (or male entrepreneurs). If policymakers are serious about encouraging entrepreneurs to venture socially, they need to understand that societal prescriptive practices can change, but it will take several decades for them to do so.

6.2 Limitations and future directions

As with any study, some inherent limitations should be highlighted. First, a consequence of our current research approach is that we assumed that the cultured capacities among female entrepreneurs stay separate and distinct throughout the process of intercultural interaction. Our work assumes that cultural practices are homogenous across society. Future research needs to examine the regional variations in the cultural practices within countries.

Second, our paper takes a broad approach to social entrepreneurship by using a mission-focused definition of social entrepreneurship (see Mair and Marti 2006). However, not every social venture is the same. There is a considerable variation among social entrepreneurs and how mission-centered their organizations are. Thus, more work is needed to unpack how cultural practices impact the development of cultured capacities for different kinds of social venturing organizations (e.g., born global, innovative, high growth, NGO, benefit corporations, low profit limited liability companies).

Finally, we also acknowledge that our study engages in strategic gender essentializing. We did this to specifically identify whether certain cultural practices affect an entrepreneur’s cultured capacities towards social entrepreneurship. Gender is a universal organizing principle in all societies. While many social scientists approach essentializing with skepticism, essentialism captures how individuals categorize others and themselves. Hence, we developed a constructivist view of gender while also essentializing gender via empirical methods to make material claims about the consequences associated with the construct. Future research would benefit from understanding gender beyond the binary perspective, and examine how non-binary entrepreneurs (persons who identify with neither male nor female identities) or gender fluid (persons who fluctuate between gender categories or express multiple at once) are affected by the broader cultural practices of their society, since such entrepreneurs’ would need to actively construct their gender identity on a daily basis.

7 Conclusion

Practice theory recognizes the interdependent and context-creating connections between macro- and micro-phenomena in entrepreneurship. This study contributes to our understanding of female entrepreneurship by using a practice perspective to unpack how cultural practices can enable or constrain an entrepreneur’s ability to practice social entrepreneurship. Our study starts a conversation about the role cultural practices and gender in developing cultured capacities towards social entrepreneurship, offering valuable insights for research and practice. We hope that this study will encourage scholars to notice how practice theory utilizes a perspective that informs our understanding of culture, gender and social entrepreneurship in cross-cultural entrepreneurship research.

Notes

In entrepreneurship, culture is often theoretically framed as a set of shared beliefs and norms (i.e., the way things should be), as it is assumed that values drive practices. However, this so-called cultural values approach has its weaknesses, since cultural values do not necessarily correspond with cultural practices, i.e., the way people behave in their environments (Maseland and Van Hoorn 2009). Findings of the GLOBE project show that negative correlations between cultural values and cultural practices exist in seven out of nine cultural dimensions, while only one cultural dimension showed a positive relationship between values and practices (House et al. 2002). This raises the question of whether cultural practices and not cultural values can better explain entrepreneurial activities across countries. And in turn, why our study adds value to the entrepreneurship discourse by examining cultural practices.

Recently, scholars in entrepreneurship have also drawn on contemporary practice theory to advance work on entrepreneurship as practice (Johannisson 2011).

Practices were measured with survey items that assessed “what is” or “what are” common institutional practices in society, also known as patterns of practice. They represented the way things were being practiced within a culture. Values were measured with survey items that assessed “what should be,” allowing respondents to expressed judgment. They reflected the respondents’ aspirations and desires in terms of the way things should be done in society (Javidan et al. 2005).

Interestingly, recent research drawing on social role theory, looking at perceptions of the overall general population, finds that social entrepreneurship is perceived as having attributes associated with both masculinity and femininity (Gupta et al. 2019).

In societies characterized by high uncertainty avoidance, individuals desire structure. In contrast, countries low in uncertainty avoidance tend to practice simple processes, decreasing the amount of formalization; they are also opportunistic and enjoy risk-taking (Javidan et al. 2006). Thus, uncertainty avoidance reflects how members of a culture can cope with unstructured situations.

Nascent entrepreneurs are actively involved in the creation or development of a venture that has yet to experience positive cash flow and will be owners. Similarly, baby business owners are those whose new ventures are less than 42 months old and have a positive cash flow. Finally, established business owners are over 42 months old and have positive cash flow.

In business research, ICC values of 0.05, 0.10, and 0.15 are considered as small, medium, and large, respectively; multilevel specification is required (Hox et al. 2010).

See Supplementary information online for further results and post hoc analysis of data.

References

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. EntrepreneurshipTheory and Practice, 30(5), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781847204387.00017.

Autio, E., Pathak, S., & Wennberg, K. (2013). Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviors. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 334–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/14632440110094632.

Badjo, L., & Dickson, M. W. (2001). Perceptions of organizational culture and women’s advancement in organizations: a cross-cultural examination. Sex Roles, 45, 339–414.

Bergmann, H., Mueller, S., & Schrettle, T. (2014). The use of global entrepreneurship monitor data in academic research: a critical inventory and future potentials. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 6(3), 242–276. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2014.064691.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford university press.

Brewer, P., & Venaik, S. (2010). GLOBE practices and values: a case of diminishing marginal utility? Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8), 1316–1324. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.23.

Brieger, S. A., & De Clercq, D. (2019). Entrepreneurs’ individual-level resources and social value creation goals: the moderating role of cultural context. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(2), 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0503.

Brieger, S. A., & Gielnik, M. M. (2020). Understanding the gender gap in immigrant entrepreneurship: a multi-country study of immigrants’ embeddedness in economic, social, and institutional contexts. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00314-x.

Brieger, S. A., Terjesen, S. A., Hechavarría, D. M., & Welzel, C. (2019). Prosociality in business: a human empowerment framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4045-5.

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F. M., & Kritikos, A. S. (2009). Risk attitudes of nascent entrepreneurs–new evidence from an experimentally validated survey. Small Business Economics, 32(2), 153–167.

Canestrino, R., Ćwiklicki, M., Magliocca, P., & Pawełek, B. (2020). Understanding social entrepreneurship: a cultural perspective in business research. Journal of Business Research, 110, 132–143.

Chell, Elizabeth. (2013). Review of skill and the entrepreneurial process. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 19(1), 6–31.

De Clercq, D., Brieger, S. A., & Welzel, C. (2019). Leveraging the macro-level environment to balance work and life: an analysis of female entrepreneurs’ job satisfaction. Small Business Economics, Online first. https://10.1007/s11187-019-00287-x

Dees, J. G., Emerson, J., & Economy, P. (2002). Enterprising nonprofits: a toolkit for social entrepreneurs. New York: Wiley.

DiVito, L., & Bohnsack, R. (2017). Entrepreneurial orientation and its effect on sustainability decision tradeoffs: The case of sustainable fashion firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 569–587.

Dwivedi, A., & Weerawardena, J. (2018). Conceptualizing and operationalizing the social entrepreneurship construct. Journal of Business Research, 86, 32–40.

Gelman, A., & Loken, E. (2014). The statistical crisis in science: data-dependent analysis—a “garden of forking paths”—explains why many statistically significant comparisons don’t hold up. American Scientist, 102(6), 460–466.

Gelman, A., & Stern, H. (2006). The difference between “significant” and “not significant” is not itself statistically significant. The American Statistician, 60(4), 328–331.

Gilligan, C. (1988). Mapping the moral domain: a contribution of women’s thinking to psychological theory and education. Center for the Study of Gender, Education, and Human Development, Harvard University, Graduate School of Education.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: a journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. New York, NY: Paulist Press.

Greene, B. A., & DeBacker, T. K. (2004). Gender and orientations toward the future: links to motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 16(2), 91–120. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000026608.50611.b4.

Gupta, V. K., Wieland, A. M., & Turban, D. B. (2019). Gender characterizations in entrepreneurship: a multi-level investigation of sex-role stereotypes about high-growth, commercial, and social entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12495.

Hamington, M., & Sander-Staudt, M. (Eds.). (2011). Applying care ethics to business (Vol. 34). Springer Science & Business Media.

Hechavarría, D. M., Terjesen, S. A., Ingram, A. E., Renko, M., Justo, R., & Elam, A. (2017). Taking care of business: the impact of culture and gender on entrepreneurs’ blended value creation goals. Small Business Economics, 48(1), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9747-4.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage publications. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490867.

House, R. J., & Javidan, M. (2004). Overview of GLOBE. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, Leadership, and Organizations. The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies (pp. 9–28). Thousand Oaks: Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105278546.

House, R. J., Quigley, N. R., & de Luque, M. S. (2010). Insights from Project GLOBE: Extending global advertising research through a contemporary framework. International Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 111–139.

House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P., & Dorfman, P. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: an introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(01)00069-4.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: the GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105278546.

Howaldt, J., Domanski, D., & Schwarz, M. (2015). Rethinking social entrepreneurship: the concept of social entrepreneurship under the perspective of socio-scientific innovation research. Journal of Creativity and Business Innovation, 1(1), 88–98.

Javidan, M., Stahl, G. K., Brodbeck, F., & Wilderom, C. P. (2005). Cross-border transfer of knowledge: cultural lessons from Project GLOBE. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(2), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.16962801.

Javidan, M., House, R. J., Dorfman, P. W., Hanges, P. J., & De Luque, M. S. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: a comparative review of GLOBE's and Hofstede's approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 897–914. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400234.

Johannisson, B. (2011). Towards a practice theory of entrepreneuring. Small Business Economics, 36(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9212-8.

Kozlowski, S. W., & Klein, K. J. (2000). A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel Theory, Research and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions and New Directions (pp. 3–90). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lehrke, A. S., & Sowden, K. (2017). Servant leadership and gender. In Servant leadership and followership (pp. 25–50). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lepoutre, J., Justo, R., Terjesen, S., & Bosma, N. (2013). Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrepreneurship activity: the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor social entrepreneurship study. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 693–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9398-4.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: a source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.002.

Maseland, R., & Van Hoorn, A. (2009). Explaining the negative correlation between values and practices: a note on the Hofstede–GLOBE debate. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(3), 527–532. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.68.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ.

Meek, W. R., Pacheco, D. F., & York, J. G. (2010). The impact of social norms on entrepreneurial action: evidence from the environmental entrepreneurship context. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(5), 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.007.

Mueller, S. L. (2004). Gender gaps in potential for entrepreneurship across countries and cultures. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 199.

Parboteeah, K. P., Addae, H. M., & Cullen, J. B. (2012). Propensity to support sustainability initiatives: a cross-national model. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(3), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0979-6.

Patterson, O. (2014). Making sense of culture. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 1–30.

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: a development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432.

Renko, M. (2013). Early challenges of nascent social entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(5), 1045–1069. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00522.x.

Reynolds, P., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., De Bono, N., Servais, I., et al. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231.

Ross-Smith, A., & Huppatz, K. (2010). Management, women and gender capital. Gender, Work and Organization, 17(5), 547–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00523.x.

Russell, R. F., & Gregory Stone, A. (2002). A review of servant leadership attributes: developing a practical model. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23(3), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730210424.

Santos, F. M. (2012). A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 335–351.

Schatzki, T. R. (2005). Peripheral vision: the sites of organizations. Organization Studies, 26(3), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050876.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (2012). Discrete dependent variables. Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling, 304-307.

Stephan, U., Uhlaner, L. M., & Stride, C. (2015). Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(3), 308–331.

Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095521.

Swidler, A. (2013). Talk of love: How culture matters. University of Chicago Press.

Taras, V., Kirkman, B. L., & Steel, P. (2010). Examining the impact of culture’s consequences: a three-decade, multilevel, meta-analytic review of Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(3), 405.

Toh, S. M., & Leonardelli, G. J. (2012). Cultural constraints on the emergence of women as leaders. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 604–611.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview.

VanSandt, C. V., Shepard, J. M., & Zappe, S. M. (2006). An examination of the relationship between ethical work climate and moral awareness. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(4), 409–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9030-8.

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising. Cambridge University Press.

Wennekers, S., Thurik, R., van Stel, A., & Noorderhaven, N. (2007). Uncertainty avoidance and the rate of business ownership across 21 OECD countries, 1976–2004. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 17(2), 133–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-006-0045-1.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & society, 1(2), 125–151.

Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2002). A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 699–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.699.

Zahra, S. A., Korri, J. S., & Yu, J. (2005). Cognition and international entrepreneurship: implications for research on international opportunity recognition and exploitation. International business review, 14(2), 129–146.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2015). Putting time in perspective: a valid, reliable individual-differences metric. In Time perspective theory; review, research and application (pp. 17–55). Cham: Springer.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Annette L. Ranft for organizing the 2015 Southern Management Association Paper Development Workshop, where an earlier version of this manuscript was presented. In addition, the authors would like to thank Amanda Elam for her feedback during the paper development process. Our thanks also go to the guest editors of this special issue as well as to the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments, criticism, and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 322 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hechavarría, D.M., Brieger, S.A. Practice rather than preach: cultural practices and female social entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 58, 1131–1151 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00437-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00437-6

Keywords

- Culture

- Entrepreneurship

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor

- Global leadership and effectiveness study

- Female entrepreneurship

- Social entrepreneurship