Abstract

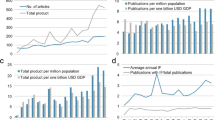

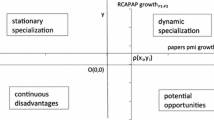

The number of scientific papers published by researchers in Africa has been rising faster than the total world scientific output in recent years. This trend is relevant, as for a long period up until 1996, Africa’s share of the world scientific output remained below 1.5 %. The propensity to publish in the continent has risen particularly fast since 2004, suggesting that a possible take-off of African science is taking place. This paper highlights that, in parallel with this most recent growth in output, the apparent productivity of African science, as measured by publications to gross domestic product, has risen in recent years to a level above the world average, although, when one looks at the equivalent ratio after it has been normalized by population, there is still a huge gap to overcome. Further it is shown that publications from those few African countries whose scientific communities demonstrate higher levels of specialization and integration in international networks, have a higher impact than the world average. Additionally, the paper discusses the potential applications of the new knowledge that has been produced by African researchers, highlighting that so far, South Africa seems to be the only African country where a reasonable part of that new knowledge seems to be connecting with innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

NEPAD stands for The New Partnership for Africa's Development.

Addresses are taken from the WoS™ file of each publication belonging to the indexes analysed. The address consolidation process is a complex scheme which is made jointly with some universities cyclically.

To simplify the analysis, Africa was divided in three regions Northern Africa (Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Sudan, Libya); Central Africa (Nigeria, Kenya, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, Ghana, Senegal, The Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Madagascar, Benin, Gambia, Gabon, Mali, Niger, The Republic of the Congo, Togo, Eritrea, Guinea Bissau, Rwanda, Mauritania, The Central African Republic, Guinea, Chad, Burundi, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Comoros, Equatorial Guinea, Cape Verde, Djibouti, Sao Tome & Principe, Somalia); Southern Africa (South Africa, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi, Zambia, Namibia, Mozambique, Mauritius, The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Swaziland, The Seychelles, Angola, Lesotho). These groups broadly correspond to the grouping employed by the UN, although the five UN groups have been compressed into three, with the nations designated by the UN as “eastern”, “middle” and “western” merged into a “central” region. South Sudan was the only African country recognized by the UN left out because they became an independent state very recently, on the 9th of July 2011. A similar methodology was used by Adams et al. (2010).

An aspect that could be researched further by research in the future, is to assess whether the adding of scientific journals headquartered in African countries to the Thomson Reuters databases in recent years, may have had an impact upon observable trends (Kahn 2011).

International comparisons of scientific productivity could also be carried out by dividing the number of scientific papers by the R&D workforce. However, the lack of available data and the possible unreliability of the statistics on the research workforce in some countries (NEPAD 2010), left us with little confidence to take that direction.

This section only provides aggregate information for all scientific areas. Information can however be provided on request for the impact of each of the 22 ESI areas across the 53 countries analysed in this paper. The main caveat would be that, for many countries, the number of publications in some areas is so small (in most cases 0) that it does not permit such calculations.

For each of the disciplinary areas mentioned above, and taking as a reference the value of one for the average world impact, the areas and countries which perform best are as follows: Immunology (Tanzania—1.25; Malawi—1.22; Mozambique—2.04), Clinical medicine (Kenya—1.26; Uganda—1.17; Tanzania—1.19; Zambia—1.30; Mali—1.25; Mozambique—1.54), Microbiology (Uganda—1.55; Tanzania—1.39) and Social sciences (Kenya—1.29; Uganda—1.33; Tanzania—1.64; Zambia—1.38; Malawi—1.78).

This refers to the “Science-push model” (in which there is a causal relationship leading from basic science to technology and then on to the market) and the “demand-pull model” (in which the needs of the market determine the rate of new innovations).

References

Adams, J. (2013). Collaborations: The fourth age of research. Nature, 497, 557–560.

Adams, J., Gurney, K. C., & Leydesdorff, L. (2014). International collaboration clusters in Africa. Scientometrics, 98, 547–556.

Adams, J., King, C., & Hook, D. (2010). Africa, pp. 1–9. Global research report: Africa, Thomson Reuters. ISBN 1-904431-25-9.

African Progress Report. (2013). Equity in extractives: Stewarding Africa’s natural resources for all. Geneva: Africa Progress Panel.

Albuquerque, E. M. (2004). Science and technology systems in less developed countries. In H. F. Moed, W. Glanzel, & U. Schmoch (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative science and technology research (pp. 759–778). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

ANSTI. (2005). State of science and technology training institutions in Africa. Report by the African network of scientific and technological institutions. Nairobi: UNESCO.

Arunachalam, S. (2004). Science on the periphery: Bridging the information divide. In H. F. Moed, W. Glanzel, & U. Schmoch (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative science and technology research (pp. 163–183). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Balassa, B. (1965). Trade liberalisation and “Revealed” comparative advantage. The Manchester School, 33(2), 99–123.

Bornmann, L., de Moya-Anegón, F., & Leydesdorff, L. (2012). The new excellence indicator in the World report of the SCImago institutions rankings. Journal of Informetrics, 6(3), 333–335.

Bornmann, L., & Leydesdorff, L. (2013). Macro-indicators of citation impacts of six prolific countries: InCites™ data and the statistical significance of trends. PLoS One, 8(2), e56768.

Bujoreanu, L. (2013). The power of mobile: Saving Uganda’s banana crop. World Bank Blogs. http://blogs.worldbank.org/ic4d/the-power-of-mobile-saving-ugandas-banana-crop. Accessed May 07, 2014.

Docquier, F., Lohest, O., & Marfouk, A. (2007). Brain drain in developing countries. World Bank Economic Review, 21, 193–218.

Fournie, J. J., Gaits, F., & Bonneville, M. (2005). Science and society—Promoting the learning of immunology in developing countries. Nature Reviews Immunology, 5, 893–898.

Garfield, E. (1983). Mapping science in the third World. Science and Public Policy, June, 112–127.

Gibbons, M., & Johnston, R. (1974). The roles of science in technological innovation. Research Policy, 3(3), 220–242.

Hassan, M. H. (2002). Science and Africa’s salvation. Project syndicate. http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/science-and-africa-s-salvation. Accessed December 18, 2013.

InCites™ Thomson Reuters. (2013). Data processed 20 March, 2013. Data source: Web of science. This data is reproduced under a license from Thomson Reuters to the University of Lisbon.

UN News Centre (2009). Nigeria surpasses hollywood as world’s second largest film producer. UN News Centre. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=30707#.UwcmPUJ_t08. Accessed May 07, 2014.

Irikefe, V., Vaidyanathan, G., Nordling, L., Twahrirwa, A., Nakkazi, E., & Monastersky, R. (2011). The view from the frontline. Nature, 474, 556–559.

Juma, C. (2008). Agricultural innovation and economic growth in Africa: renewing international cooperation. International Journal of Technology and Globalisation, 4, 256–275.

Kahn M. (2011). A bibliometric analysis of South Africa’s scientific outputs—some trends and implications. South African Journal of Science, 107 (1–2), 1–6. 10.4102/sajs.v107i1/2.406.

Laursen, K. (2000). Do export and technological specialization patterns co-evolve in terms of convergence or divergence? Evidence from 19 OECD countries, 1971–1991. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 10, 415–436.

Leydesdorff, L., Wagner, C., Park, H. W., & Adams, J. (2013). International collaboration in science: The global map and the network. El Profesional de la Información, 22(1), 87–94.

Lundvall, B.-A. (2009). Innovation in Africa—towards a realistic vision. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 1, 212–219.

Megnibeto, E. (2013). International collaboration in scientific publishing: the case of West Africa (2001–2010). Scientometrics, 96, 761–783.

Muchie, M. (Ed.). (2003). The making of African-Nation: Pan-Africanism and the African renaissance. London: Adonis & Abbey.

Narvaez-Berthelemot, N., Russell, J. M., Arvanitis, R., Waast, R., & Gaillard, J. (2002). Science in Africa: An overview of mainstream scientific output. Scientometrics, 54(2), 229–241.

Nchinda, T. C. (2002). Research capacity strengthening in the South. Social Science and Medicine, 54, 1699–1711.

NEPAD Planning and Coordination Agency. (2003). Declaration of the first NEPAD ministerial conference on science and technology. Johannesburg: NEPAD Planning and Coordination Agency.

NEPAD Planning and Coordination Agency. (2010). African innovation outlook 2010. Pretoria: NEPAD Planning and Coordination Agency.

Omamo, S. W., & Lynam, J. K. (2003). Agricultural science and technology policy in Africa. Research Policy, 32, 1681–1694.

Pouris, A. (2010). A scientometric assessment of the Southern Africa Development Community: Science in the tip of Africa. Scientometrics, 85, 145–154.

Pouris, A., & Ho, Y. (2014). Research emphasis and collaboration in Africa. Scientometrics, 98, 2169–2184.

Pouris, A., & Pouris, A. (2009). The state of science and technology in Africa (2000–2004): A scientometric assessment. Scientometrics, 79, 297–309.

The Economist (2013a). Africa rising: A hopeful continent. The economist. http://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21572377-african-lives-have-already-greatly-improved-over-past-decade-says-oliver-august. Accessed December 18, 2013.

The Economist (2013b). Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone: Tired of war. Why fighting across much of the continent has died down in recent years. The economist. http://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21572378-why-fighting-across-much-continent-has-died-down-recent-years-tired-war. Accessed December 18, 2013.

Tijssen, R. J. W. (2007). Africa’s contribution to the worldwide research literature: new analytical perspectives, trends, and performance indicators. Scientometrics, 71(2), 303–327.

Toivanen, H., & Ponomariov, B. (2011). African regional innovations systems: Bibliometric analysis of research collaboration patterns 2005–2009. Scientometrics, 88(2), 471–493.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2013). Human development report. The rise of the south: Human progress in a diverse world. New York: United Nations.

UNESCO (2014). UNESCO institute for statistics database. Retrieved from: http://data.uis.unesco.org/. Accessed May 07, 2014.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) (2010). Sub-Saharan Africa. In UNESCO science report 2010: The current status of science around the World (pp. 279–319). UNESCO publishing.

Uthman, O. A., & Uthman, M. B. (2007). Geography of Africa biomedical publications: An analysis of 1996–2005 pubmed papers. International Journal of Health Geographics, 6, 46–56. doi:10.1186/1476-072X-6-46.

Waast, R., & Rossi, P.-L. (2010). Scientific production in Arab countries: A bibliometric perspective. Science Technology and Society, 15(2), 339–370.

Waltman, L., & Van Eck, N. J. (2013). Source normalized indicators of citation impact: An overview of different approaches and an empirical comparison. Scientometrics, 96(3), 699–716.

Web of Science™ Thomson Reuters (2013). Data processed December 18, 2013.

World Bank (2013). World development indicators database. Retrieved from: http://databank.worldbank.org. Accessed March 20, 2013.

Zegeye, A., & Vambe, M. (2006). Knowledge production and publishing in Africa. Development Southern Africa, 23(3), 333–349.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Confraria, H., Godinho, M.M. The impact of African science: a bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 102, 1241–1268 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1463-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1463-8