Abstract

We investigated, experimentally, the contention that the folk view, or naïve theory, of time, amongst the population we investigated (i.e. U.S. residents) is dynamical. We found that amongst that population, (i) ~ 70% have an extant theory of time (the theory they deploy after some reflection, whether it be naïve or sophisticated) that is more similar to a dynamical than a non-dynamical theory, and (ii) ~ 70% of those who deploy a naïve theory of time (the theory they deploy on the basis of naïve interactions with the world and not on the basis of scientific investigation or knowledge) deploy a naïve theory that is more similar to a dynamical than a non-dynamical theory. Interestingly, while we found stable results across our two experiments regarding the percentage of participants that have a dynamical or non-dynamical extant theory of time, we did not find such stability regarding which particular dynamical or non-dynamical theory of time they take to be most similar to our world. This suggests that there might be two extant theories in the population—a broadly dynamical one and a broadly non-dynamical one—but that those theories are sufficiently incomplete that participants do not stably choose the same dynamical (or non-dynamical) theory as being most similar to our world. This suggests that while appeals to the ordinary view of time may do some work in the context of adjudicating disputes between dynamists and non-dynamists, they likely cannot do any such work adjudicating disputes between particular brands of dynamism (or non-dynamism).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Callender (2017).

Dynamists hold that events are ordered in terms of whether they are objectively past, present or future; the location of events within that ordering is dynamic in that a set of events, E, is future, will be present, and will then become past. According to dynamists, time flows by virtue of a set of events being objectively present, and which sets of events that is, changing. Dynamists take tensed thought and talk to pick out genuinely dynamical (A-theoretic) properties. For defenses of dynamism in its various guises see Broad (1923, 1938), Cameron (2015), Tallant (2012), Tooley (1997), Prior (1967, 1968, 1970), Gale (1968), Schlesinger (1980, 1994), Smith (1993), Craig (2000), Crisp (2003), Markosian (2004), Baron (2014), Bourne (2006), Monton (2006), Sullivan (2012) and Zimmerman (2005).

See Baron et al. (2015).

See Miller (2008).

Non-dynamists suppose that there are no objective tensed properties of properties of pastness, presentness or futurity; all that exists is an ordering of events in terms of the relations of earlier-than, later-than and simultaneous-with. Non-dynamists take tensed thought and talk to be indexical, picking out the time at which a proposition is expressed either in speech or via some doxastic state. According to non-dynamists there is no temporal flow. Defenders include Callender (2008), Lee (2014), Mellor (1981, 1998), Paul (2010), Price (1997, 2011) and Prosser (2000, 2007, 2012, 2013).

See Callender (2008).

Or, at least, they are closer to being temporal dynamists than non-dynamists.

Fuhrman et al. (2011) discuss how the spatial morphemes sháng (up) and xiá (down) are used to talk about the ordering of events, weeks, months, and so on. Earlier events are sháng (up), and later events are xiá (down). For example, ‘sháng ge yuè’ refers to the last or previous month, and ‘xiá ge yuè’ refers to the next or following month.

These are people in a large database who partake in a range of online experiments, usually in psychology, behavioral economics and sociology, for monetary compensation. While they have significant experience in completing online experiments, there is little reason to think that these people will have a particular interest in, or knowledge of, philosophy.

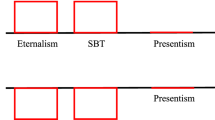

The view that only the present exists, and that the present changes. See Tallant (2012).

The view that the past, present, and future exist, but that which moment is objectively present changes as the ‘light’ of presentness moves over a fixed four-dimensional block. More recent versions of the view are somewhat more sophisticated than this, where the block is often rather unlike the fixed block of B-theoretic eternalism. See for instance Cameron (2015) and Skow (2015).

Also known as the block universe theory. This is the view that the past, present, and future exist, and no moment in objectively present. Instead, presentness is a mere indexical that picks out wherever one happens to be. See Mellor (1991, 1998). As we will present the theory, it is a theory in which although there is no temporal flow or passage (since there is no objective present to move) nevertheless, time has a direction: it points from earlier, to later. For discussion of direction and the B-theory see Tegtmeier (1996) and Maudlin (2007).

One might worry that, given that the C-theory and quantum gravity theories are not terribly popular amongst philosophers, these theories might generally strike people as being implausible. Then one might worry that if we eliminate these theories, it might be that people’s choice between the remaining accounts is at chance, which would undermine our claims in this paper. If this worry is right, then if we exclude those participants who chose the C-theory or the quantum gravity theory as being most like our world, the remaining participants should be evenly distributed amongst the remaining theories of time (moving spotlight, presentism, growing block, block universe). We do not find this. Instead, participants preferred the growing block over the other theories (X2 (3, N = 284) = 40.596, p < .001). We would like to thank an anonymous referee for raising this concern.

It makes no difference to the reported result if we include those who failed to correctly answer 2 of 3 comprehension questions for the vignette they chose as being most like the actual world. There was still no significant difference in confidence between those that think the actual world is most like a dynamical theory of time (M = 4.76, SD = 1.48) or most like a non-dynamical theory of time (M = 4.63, SD = 1.56; t(512) = 0.954, p = .34).

It makes no difference to the reported result if we include those who failed to correctly answer 2 of 3 comprehension questions for the vignette they chose as being most like the actual world. There was still no significant difference in level of agreement for the statement “I have some understanding of what science tells us about the nature of time” between those who think the actual world is most like a dynamical theory of time (M = 5.08, SD = 1.34) and those who think the actual world is most like a non-dynamical theory of time (M = 5.18, SD = 1.32; t(512) = 0.851, p = .395).

It makes no difference to the reported result if we include those who failed to correctly answer 2 of 3 comprehension questions for the vignette they chose as being most like the actual world. There was still no significant difference in level of agreement for the statement “It is very likely that through science we will discover that Universe [A/B/C/D/E/F] is most like our Universe” between those who think the actual world is most like a dynamical theory of time (M = 4.89, SD = 1.41) and those who think the actual world is most like a non-dynamical theory of time (M = 4.84, SD = 1.32; t(512) = 0.414, p = .679).

It makes no difference to the reported result if we include those who failed to correctly answer 2 of 3 comprehension questions for the vignette they chose as being most like the actual world. There was still no significant difference in level of agreement for the statement “It just seems obvious that Universe [A/B/C/D/E/F] is most like our Universe” between those who think the actual world is most like a dynamical theory of time (M = 4.76, SD = 1.45) and those who think the actual world is most like a non-dynamical theory of time (M = 4.68, SD = 1.47; t(512) = 0.595, p = .552).

References

Barbour, J. (1994a). The timelessness of quantum gravity: I. The evidence from the classical theory. Classical Quantum Gravity, 11(12), 2853–2873.

Barbour, J. (1994b). The timelessness of quantum gravity: II. The appearance of dynamics in static configurations. Classical Quantum Gravity, 11(12), 2875–2897.

Barbour, J. (1999). The end of time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bardon, A. (2013). A brief history of the philosophy of time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baron, S. (2014). The priority of the now. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 96(3), 325–348.

Baron, S., Cusbert, J., Farr, M., Kon, M., & Miller, K. (2015). Temporal experience, temporal passage and the cognitive sciences. Philosophy Compass, 10(8), 56–571.

Baron, S., & Miller, K. (2015a). What is temporal error theory? Philosophical Studies, 172(9), 2427–2444.

Baron, S., & Miller, K. (2015b). Our concept of time. In B. Mölder, V. Arstila, & P. Ohrstrom (Eds.), Philosophy and psychology of time. Berlin: Springer.

Boroditsky, L. (2001). Does language shape thought? English and Mandarin speakers’ conceptions of time. Cognitive Psychology, 43, 1–22.

Boroditsky, L., Fuhrman, O., & McCormick, K. (2011). Do English and Mandarin speakers think about time differently? Cognition, 118, 123–129.

Bourne, C. (2006). A future for presentism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Braddon-Mitchell, D. (2013). Against the illusion theory of temporal phenomenology. CAPE Studies in Applied Ethics, 2, 211–233.

Broad, C. D. (1923). Scientific thought. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Broad, C. D. (1938). Examination of McTaggart’s philosophy: Vol II part I. Cambridge: CUP.

Buckwalter, W., & Stich, S. (2014). Gender and philosophical intuition. In J. Knobe & S. Nichols (Eds.), Experimental philosophy (Vol. 2). New York: OUP.

Callender, C. (2008). The common now. Philosophical Issues, 18(1), 339–361.

Callender, C. (2017). What makes time special?. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cameron, R. P. (2015). The moving spotlight: An essay on time and ontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Casasanto, D., & Bottini, R. (2014). Mirror reading can reverse the flow of time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 473–479.

Chen, J. Y. (2007). Do Chinese and English speakers think about time differently? Failure of replicating Boroditsky (2001). Cognition, 104, 427–436.

Craig, W. L. (2000). The tensed theory of time: A critical examination. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Crisp, T. (2003). Presentism. In M. Loux & D. Zimmerman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dainton, B. (2011). Time, passage and immediate experience. In C. Callender (Ed.), Oxford handbook of philosophy of time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deng, N. (2013). On explaining why time seems to pass. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 51(3), 367–382.

Deng, N. (2018). On ‘Experiencing time’: A response to Simon Prosser. Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy, 61(3), 281–301.

Elga, A. (2005). Isolation and folk physics. In H. Price & R. Corry (Eds.), Causation, physics, and the constitution of reality: Russell’s Republic revisited. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Evans, V. (2003). The structure of time: Language, meaning and temporal cognition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Forbes, G. (2016). The growing block’s past problems. Philosphical Studies, 173(3), 699–709.

Fuhrman, O., & Boroditsky, L. (2010). Cross-cultural differences in mental representations of time: Evidence from an implicit non-linguistic task. Cognitive Science, 34, 1430–1451.

Fuhrman, O., McCormick, K., Chen, E., Jiang, H., Shu, D., Mao, S., et al. (2011). How linguistic and cultural forces shape conceptions of time: English and Mandarin time in 3D. Cognitive Science, 35, 1305–1328.

Gale, R. M. (1968). The language of time. Virginia: Humanities Press.

Hoerl, C. (2014). Do we (seem to) perceive passage? Philosophical Explorations, 17, 188–202.

Kim, M & Yuan, Y. (2015). No cross-cultural differences in the Gettier car case intuition: A replication study of Weinberg et al. 2001. Episteme, 12(3), 355–361.

Le Poidevin, R. (2007). The images of time: An essay on temporal representation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee, G. (2014). Temporal experience and the temporal structure of experience. Philosophers’ Imprint, 14(1), 1–21.

Livengood, J., & Machery, E. (2007). The folk probably don’t think what you think they think: Experiments on causation by absence. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 31(1), 107–127.

Machery, E., Mallon, R., Nichols, S., & Stephen, S. (2004). Semantics, cross-cultural style. Cognition, 92(3), 1–12.

Markosian, N. (2004). A defense of presentism. In D. Zimmerman (Ed.), Oxford studies in metpahysics (Vol. I). Oxford: OUP.

Maudlin, T. (2007). The metaphysics within physics. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mellor, H. (1981). Real time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mellor, D. H. (1991). Causation and the direction of time. Erkenntnis, 35(1–3), 191–203.

Mellor, H. (1998). Real time II. London: Routledge.

Miller, K. (2008). Backwards causation, time and the open future. Metaphysica, 9(2), 173–191.

Miller, K., Holcombe, A., & Latham, A. J. (2018). Temporal phenomenology: Phenomenological illusion versus cognitive error. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1730-y.

Monton, B. (2006). Presentism and quantum gravity. In D. Dieks (Ed.), The ontology of spacetime. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Nagel, J., Valerie, S. J., & Mar, R. A. (2013). Lay denial of knowledge for justified true beliefs. Cognition, 129(3), 652–661.

Norton, J. D. (2003). Causation as folk science. Philosophers’ Imprint, 3, 1–22.

Núñez, R., Cooperrider, K., Doan, D., & Wassmann, J. (2012). Contours of time: Topographic construals of past, present, and future in the Yupno valley of Papua New Guinea. Cognition, 124(1), 25–35.

Paul, L. A. (2010). Temporal experience. Journal of Philosophy, 107(7), 333–359.

Price, H. (1997). Time’s arrow & Archimedes’ point: New directions for the physics of time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Price, H. (2007). Causal perspectivalism. In H. Price & R. Corry (Eds.), Causation, physics and the constitution of reality: Russell’s Republic revisited. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Price, H. (2011). The flow of time. In C. Callender (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of time (pp. 276–311). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prior, A. (1967). Past, present and future. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Prior, A. (1968). Papers on time and tense. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prior, A. (1970). The notion of the present. Staium Generale, 23, 245–248.

Prosser, S. (2000). A new problem for the A-theory of time. The Philosophical Quarterly, 50(201), 494–498.

Prosser, S. (2007). Could we experience the passage of time? Ratio, 20, 75–90.

Prosser, S. (2012). Why does time seem to pass? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 85, 92–116.

Prosser, S. (2013). Passage and perception. Noûs, 47, 69–84.

Schlesinger, G. (1980). Aspects of time. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Schlesinger, G. (1994). Temporal becoming. In N. Oakland & Q. Smith (Eds.), The new theory of time. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Seyedsayamdost, H. (2015). On normativity and epistemic intuitions: Failure of replication. Episteme, 12(1), 95–116.

Shanahan, M. (1996). Folk learning and naive physics. In A. Clark & P. J. R. Millican (Eds.), Connectionism, concepts, and folk psychology: The legacy of Alan Turing (Vol. 2). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sinha, C., & Gardenfors, P. (2014). Time, space, and events in language and cognition: A comparative view. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Issue: Flow of time, 40, 1–10.

Skow, B. (2015). Objective becomoing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Q. (1993). Language and time. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stich, S. (1990). The fragmentation of reason: Preface to a pragmatic theory of cognitive evaluation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sullivan, M. (2012). The minimal A-theory. Philosophical Studies, 158(2), 149–174.

Tallant, J. (2012). (Existence) presentism and the A-theory. Analysis, 72(4), 673–681.

Tegtmeier, E. (1996). The direction of time: A problem of ontology, not of physics. In J. Faye (Ed.), Perspectives on time. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Tooley, M. (1997). Time, tense, and causation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Torrengo, G. (2017). Feeling the passing of time. The Journal of Philosophy, 114(4), 165–188.

Weinberg, J. M., Nichols, S., & Stich, S. (2001). Normativity and epistemic intuitions. Philosophical Topics, 29(1/2), 429–460.

Whorf, B. L. (1950). An American Indian model of the universe. International Journal of American Linguistics, 16, 67–72.

Zimmerman, D. (2005). The A-theory of time, the B-theory of time, and ‘Taking Tense Seriously. Dialectica, 59(4), 401–457.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to David Braddon-Mitchell for helpful discussion. Andrew James Latham thanks the Ngāi Tai Ki Tāmaki Tribal Trust for their support. Funding was provided by Australian Research Council (Grant Nos. FT170100262, DP18010010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Latham, A.J., Miller, K. & Norton, J. Is our naïve theory of time dynamical?. Synthese 198, 4251–4271 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02340-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02340-4