Abstract

Human beings have been recently reviewed as ‘metaorganisms’ as a result of a close symbiotic relationship with the intestinal microbiota. This assumption imposes a more holistic view of the ageing process where dynamics of the interaction between environment, intestinal microbiota and host must be taken into consideration. Age-related physiological changes in the gastrointestinal tract, as well as modification in lifestyle, nutritional behaviour, and functionality of the host immune system, inevitably affect the gut microbial ecosystem. Here we review the current knowledge of the changes occurring in the gut microbiota of old people, especially in the light of the most recent applications of the modern molecular characterisation techniques. The hypothetical involvement of the age-related gut microbiota unbalances in the inflamm-aging, and immunosenescence processes will also be discussed. Increasing evidence of the importance of the gut microbiota homeostasis for the host health has led to the consideration of medical/nutritional applications of this knowledge through the development of probiotic and prebiotic preparations specific for the aged population. The results of the few intervention trials reporting the use of pro/prebiotics in clinical conditions typical of the elderly will be critically reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The microbial community which inhabits the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract is widely recognized as a key component of GI homeostasis, playing an essential role in maintaining human health. The perceived importance of the intestinal microbiota in human physiology culminated in the review of human beings as ‘metaorganisms’ derived from millennia of co-evolution with their own indigenous intestinal microbiota (Turnbaugh et al. 2007). In the light of the metaorganism hypothesis, a more holistic view of the process of human ageing has been suggested where the ageing of the microbial counterpart is regarded as an important actor. The balance of the intestinal microbiota is inevitably affected by the physiological changes of the GI tract induced by the ageing process itself, as well as other age-related events, i.e. modification in diet and lifestyle, and reduction of functionality of the immune system (IS). Therefore, changes in the composition and structure of the intestinal microbiota could be related to distinctive conditions of the elderly, such as frailty, immunosenescence, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and sarcopenia.

Although this is a field of growing interest because of the increasing proportion of aged individuals in the Western countries (Cohen 2003; Christensen et al. 2009), studies focused on the changes which occur in the intestinal microbiota during the ageing process and their possible consequences on the health status of the elderly are still limited. The purpose of this review is to discuss the current knowledge of the microbial diversity in the gut of elderly people. The possibility of preventing or modulating the age-associated modifications in gut microbiota through dietary supplementation (pro/prebiotics) or other approaches, aimed at obtaining beneficial effects on the host’s health, will also be reviewed.

Physiology, nutrition and lifestyle of the elderly

Physiological changes and effects of diet

In old age, there is an increased threshold for taste and smell (Weiffenbach and Bartoshuk 1992; Doty et al. 1984), and there may be subtle changes in gastrointestinal motility (Orr and Chen 2002). Masticatory dysfunction caused by loss of teeth and muscle bulk (Newton et al. 1993) can lead to the consumption of a restricted, nutritionally imbalanced diet. Edentulous persons and those who rate their health as fair or poor generally consume fewer servings of fruits and vegetables, eat a less varied diet and have a poorer quality diet than people with teeth (Ervin 2008).

Physiological functions naturally decline with age and may influence the absorption and/or metabolism of nutrients. Gastric atrophy in the elderly has been reported to be responsible for reduced absorption of calcium, iron and vitamin B12 (Russell 1992) and results in an inability to release cobalamin from food or its binding proteins (Dali-Youcef and Andrès 2009), causing vitamin B12 deficiency. Helicobacter pylori infection is also associated with vitamin B12 deficiency (Allen 2008), and epidemiological studies have demonstrated that both gastric atrophy and H. pylori infection increase with ageing (Pilotto et al. 1999; Fernández-Bañares et al. 2009). In people over 75 years, the combination of gastric atrophy and H. pylori has also been associated with lower expression of gut appetite proteins, leptin and ghrelin, which raises the possibility that H. pylori may be contributing towards undernutrition in the elderly (Salles et al. 2006).

There is higher incidence of diverticular disease in old age (Raskin 2008), currently believed to be associated with localised inflammation, and this is exacerbated by a low fibre diet (Comparato et al. 2007). Insoluble fibre from fruits and vegetables are reported to be more beneficial than cereal fibre both for the prevention and treatment of diverticular disease (Aldoori et al. 1998). Intakes of dietary fibre display differences between countries, with Sweden having the lowest intake (17.0 g/day in men aged 65–74 years) and Murcia, Spain the highest (29.4 g/day). Interestingly, UK women aged 65–74 years who are described as ‘health conscious’ have a much higher fibre intake, 24.5 g/day compared with 15.8 g/day in the general female population of this age (Cust et al. 2009). The UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) of the Elderly (Finch et al. 1998) report a significant fall in non-starch polysaccharides with increasing age, with intakes of 13.5 and 11.0 g/day for free-living and institutionalised men, respectively, and 11.0 and 9.5 g/day for women with cereals and cereal products providing about half the total fibre intake. There was a positive association between the number of bowel movements and average daily non-starch polysaccharide intake.

Constipation is more common with increasing age and is caused by inactivity, inappropriate diet, depression and confusion, certain medications and neuromuscular disorders (Wald 1993). Commonly this is treated with laxatives but ideally the consumption of whole grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables should be increased (Slavin 2008). Tailored products, such as pea hull fibre added to usual foods (Dahl et al. 2003) and oat bran (Sturtzel et al. 2010), have been shown to be helpful in improving constipation management, and oat bran was also reported to improve vitamin B12 bioavailability.

Food choice and nutrition

Dietary patterns may undergo a series of changes in older life, modulated by many age-related factors such as changes in socioeconomic status, mobility, dentition, taste, smell, digestion, appetite and conditions such as depression and dementia (Koehler and Leonhaeuser 2008). Dean et al. (2009) report that appetite, food knowledge, perceived distance to the shops, access to high-quality food products, kitchen facilities and support from friends and neighbours all contribute to the selection of a varied diet which broadly determines its nutritional quality. Living alone in old age is associated with a poor diet, even when an allowance is made for age, sex, income and educational attainment (Kharicha et al. 2007).

The quality of the diet in old age has a significant impact on morbidity and mortality (de Groot et al. 2004), and there is a growing risk of malnutrition with increasing age. For example, in a small study in the UK, Harris et al. (2008) observed that 10% of people (mean age 79 years) living in sheltered accommodation were malnourished according to the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool and Mini Nutritional Assessment. The UK NDNS of the Elderly (Finch et al. 1998) reported low riboflavin status in 40% of free-living and institutionalised men and women aged 65 years and over, low plasma vitamin C concentrations in 15% of free-living and 40% of institutionalised people, low thiamine status in 10–15% of both groups, low red blood cell folate in 8% of free-living and 19% of institutionalised people and low serum vitamin B12 in 6% of free-living and 9% of institutionalised people. There was wide inter-individual variability in all of the status measurements, reflecting variation in quality of the diet. Mean plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations <25 nmol/L were present in 8% of free-living and 37% of institutionalised people, with a clear seasonal variation and a downward trend in free-living individuals. However, this lower limit is based on preventing rickets and osteomalacia and is currently considered to be too low for the other health-related functions of vitamin D (Vieth et al. 2007; Henry et al. 2010), suggesting that the problem of inadequate vitamin D status is even more widespread in old people living in Northern Europe, particularly those who are confined indoors (Dixon et al. 2006).

The UK NDNS of the Elderly (Finch et al. 1998) reported inadequate intakes for a number of minerals, including magnesium (21–39% had intakes below the lower reference nutrient intake (LRNI), indicating a 97.5% probability of deficiency), potassium (17–42% below the LRNI) and zinc (4–13% below the LRNI), but the lack of biomarkers of status makes it impossible to confirm the presence of deficiency and the level of risk is dependent on the appropriateness of the LRNI value. In contrast, reported inadequate intakes of iron (1–6% below the LRNI) are accompanied by low haemoglobin concentrations (indicative of anaemia) in 11% and 9% of free-living and 52% and 39% of institutionalised men and women, respectively, illustrating the problem of inadequate iron supply in the diet of UK elderly, particularly those living in residential homes. In the general population across Europe, there is geographical variability in mineral intakes (Welch et al. 2009). In men aged 65–74 years, magnesium intakes ranged from 352 mg/day in Malmö, Sweden to 475 mg/day in Murcia, Spain, and in women, the lowest intake was in Naples, Italy (252 mg/day) and highest in northwest France (384 mg/day). Iron intakes also vary, with higher intakes in Southern than in Northern Europe. In men aged 65–74 years, the range was between 12.1 mg/day (Malmö, Sweden) to 19.9 mg/day (Greece); in women, the range was 8.8 mg/day (Malmö, Sweden) to 14.2 (Greece).

Drugs

Elderly patients are the recipients of more than 30% of all prescription drugs, often given as multiple treatments, so are at higher risk of compromised nutritional status because of drug–nutrient interactions, for example, loss of body electrolytes (Genser 2008). Adverse drug reactions are at least twice as common in the elderly compared to younger adults, but the side effects are not well-documented in this age group since most clinical trials exclude patients >75–80 years. Malabsorption, diarrhoea and constipation are common side effects of laxatives, antibiotics, anticholinergics and calcium channel blockers (Triantafyllou et al. 2010). However, the purported long-term adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors on vitamin B12 status have recently been refuted (den Elzen et al. 2008).

Clostridium difficile is responsible for more than 25% of all cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (Poutanen and Simor 2004). C. difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD) is a common problem in geriatric care, especially in elderly hospitalised patients with comorbid illnesses and ongoing exposure to antibiotics; prolonged stays in intensive care units may also be a risk factor for C. difficile infection (Monaghan et al. 2008; Cober and Malani 2009; Kelly 2009). Usually it occurs 2 to 3 weeks after cessation of antibiotic treatments (Barbut and Petit 2001), and although most patients are responsive to metronidazole and vancomycin therapy, 20% to 35% of them present recurrent symptoms which can end up in repeated episodes of diarrhoea over months to years, resulting in an increased morbidity and reduced quality of life (McFarland et al. 2002; Poutanen and Simor 2004).

Gut microbiota and human health

The GI tract harbours the largest and most complex bacterial ecosystem in the human body (Hattori and Taylor 2009; Neish 2009). An increasing gradient in bacterial concentration characterises the human GI tract, from stomach, to jejunum, ileum and colon, where the concentration peaks to 1011–1012 bacterial cells per gram of stool (Ley et al. 2006a; Leser and Molbak 2009). The collective genome of the gut microbial community (microbiome) contains more than 100 times the number of genes in the human genome (Backhed et al. 2005), endowing human hosts with physiological attributes they did not evolve on their own. The gut microbiota enhances the host’s metabolic capabilities by hydrolysing complex plant polysaccharides poorly digested by the human digestive system and producing short chain fatty acids (SCFA). SCFAs positively affect energy transduction in colonocytes, growth and cellular differentiation and hepatic control of the lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Cummings 1995; Topping and Clifton 2001). Moreover, several SCFAs have shown to exert anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects (Macfarlane et al. 2007). Microbes in the human gut are also responsible for the synthesis of certain essential vitamins and amino acids (Hooper et al. 2002). Other benefits provided by the gut microbiota are involved in the development and maintenance of the IS homeostasis (Round and Mazmanian 2009) and in the development and survival of the gut epithelium (Neish 2009). Finally, the gut microbiota exerts a right of ‘first occupancy’ precluding other microorganisms from invading the occupied niches (Sansonetti and Medzhitov 2009).

The total diversity of a healthy adult gut ecosystem is generally reported to be around 1,000–1,200 species-level phylogenetic types (phylotypes, defined as groups of 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequences with 97–99% of similarity) of which 75–82% is estimated to remain uncultured (Eckburg et al. 2005; Flint et al. 2007; Rajilic-Stojanovic et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2007). The vast majority of this diversity (90–99%) is confined to the bacterial phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, with the dominant Firmicutes (50–80%) primarily composed of bacteria belonging to the Clostridium clusters XIVa and IV. Other phyla represented in the human gut are Actinobacteria (3–15%), Proteobacteria (1–20%), Verrucomicrobia (0.1%), Fusobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Spyrochaetes and Lentisphaerae (Ley et al. 2006b; Turnbaugh et al. 2006; Frank et al. 2007; Andersson et al. 2008; Armougom and Raoult 2008; Dethlefsen et al. 2008; Tap et al. 2009). This adult-like structure of the gut microbiota is established approximately after the first year of life, and it is believed to remain relatively stable through healthy adulthood (Vanhoutte et al. 2004). In spite of the astonishing individual variability in terms of species and strain composition showed by the gut microbiota (Zoetendal et al. 1998, 2001; Eckburg et al. 2005; Lay et al. 2005; Ley et al. 2006a), a high degree of conservation in the expressed functions and metabolites of the gut microbiota has been reported (‘functional redundancy’; Gill et al. 2006; Mahowald et al. 2009; Tschop et al. 2009; Turnbaugh et al. 2009). On the contrary, major alterations in the gut microbiota structure, such as modifications at the level of order/phylum (dysbiosis), affect the microbiota functionality. Even if it is still impossible to define a cause–effect relation between dysbioses and the occurrence of a pathological situation, the maintenance of a balanced microbiota may represent a new frontier of biology and medicine in which new strategies for preserving human health may be identified (Hattori and Taylor 2009).

Age-related reshaping of the gut microbiota

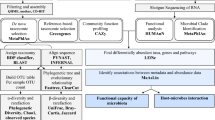

The available literature concerning the composition of gut microbiota in the elderly is sparse, and only recently the most modern characterisation techniques (Fig. 1) have been applied to this particular field of the gut microbial ecology. Results obtained by bacterial isolation techniques (Hopkins and Macfarlane 2002; Woodmansey et al. 2004) cannot be compared with data from more advanced techniques for the molecular characterisation of the microbiota, now considered essential to obtain a comprehensive view of the gut ecosystem.

Moreover, the different studies are generally not comparable since they often have different purposes, such as the relationship between microbiota and frailty (van Tongeren et al. 2005), the impact of antibiotic treatments (Bartosch et al. 2004; Woodmansey et al. 2004) and the differences between the GI health status of hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients (Bartosch et al. 2004; Zwielehner et al. 2009). Even when only healthy elderly are considered for the studies, there are discrepancies in the definition of ‘elderly’: Groups of people with a wide range of age are often recruited, on the basis of general ‘over 60’ (Mueller et al. 2006), ‘over 65’ (Woodmansey et al. 2004; Claesson et al. 2010) or ‘over 70’ (Mariat et al. 2009) criteria. This makes it very difficult to define with accuracy any ‘threshold age’ at which time the gut environment really begins to be affected by the ageing process. Striking country-related differences in the effects of age on the gut microbiota composition are also often reported, suggesting that the different nutritional habits and lifestyle of the elderly may play a role in determining the age-related modifications.

In conclusion, the definition of the gut microbiota of healthy elderly is still a challenging task. The commonly reported age-related changes in the dominant and subdominant microbiota are summarized in the next sections, and the most recent studies in the field are discussed.

Age-related modification in the dominant microbiota

Among the Firmicutes, Clostridium cluster XIVa (also called Clostridium coccoides/Eubacterium rectale group) was reported to decrease in Japanese healthy elderly aged 74–94 years (Hayashi et al. 2003), Italian over 60 years (Mueller et al. 2006) and Finnish over 70 years people (Mäkivuokko et al. 2010). Most recently, Biagi et al. (2010) reported the same modification in Italian centenarians. On the contrary, German over 60 years elderly showed inverse trend (Mueller et al. 2006). As for the Clostridium cluster IV, a well-documented ageing effect is the decrease in the Faecalibacterium prausnitzii group, a subset of this cluster, reported in Italian over 60 years (Mueller et al. 2006) and Italian centenarians (Biagi et al. 2010). On the contrary, the other European population considered in the study of Mueller et al. (France, Germany and Sweden) showed an opposite trend, as well as the Irish over 65 years elderly involved in the study of Claesson et al. (2010). The decrease of both Clostridium cluster XIVa and F. prausnitzii group members was also correlated to frailty condition, hospitalisation, antibiotic treatment and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapy (Bartosch et al. 2004; van Tongeren et al. 2005; Tiihonen et al. 2008; Zwielehner et al. 2009).

The effect of ageing on bacteria belonging to the phylum Bacteroidetes is quite confusing. A decline in the Bacteroidetes amount was showed by earlier isolation studies (Hopkins and Macfarlane 2002; Woodmansey et al. 2004) and confirmed by molecular techniques for Italian healthy over 60 years people (Mueller et al. 2006) and elderly subjects from Northern Europe, aged 71 years in average (Rajilic-Stojanovic et al. 2009). On the contrary, German healthy elderly, Austrian hospitalised elderly patients aged 78–94 years and Finnish over 70 years (Mueller et al. 2006; Zwielehner et al. 2009; Mäkivuokko et al. 2010) showed an inverse trend. Thus, the behaviour of the Bacteroidetes population during ageing seems strongly country dependent, and according to studies using 16S rRNA-based molecular techniques, a decrease in Bacteroidetes seems to be more strictly related to frailty condition, antibiotic treatment, hospitalisation and CDAD, than to the ageing process itself (Hopkins et al. 2001; Bartosch et al. 2004; van Tongeren et al. 2005).

As Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are the most dominant phyla in the gut, the ratio between these two groups of bacteria could be considered an informative parameter of the overall status of the gut microbiota. In this context, Mariat et al. (2009) reported that the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was lower in elderly people (aged 70–90 years) than in young adults, but the nationality of the enrolled subjects was not stated in the paper. This was confirmed by Claesson et al. (2010) in their recent application of pyrosequencing performed on the faecal microbiota of Irish young and elderly adults. On the contrary, Biagi et al. (2010) did not find significant differences among the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios of Italian centenarians, elderly and young adults.

Age-related modifications in the subdominant microbiota

The available studies are in general agreement reporting an age-related increase in facultative anaerobes, including streptococci, staphylococci, enterococci and enterobacteria (Gavini et al. 2001; Woodmansey et al. 2004; Mueller et al. 2006; Mäkivuokko et al. 2010; Mariat et al. 2009; Rajilic-Stojanovic et al. 2009). The enterobacteria group comprehends potentially pathogenic species, recently redefined as ‘pathobionts’, i.e. bacterial species present in small concentrations in a healthy gut environment, which can overgrow in certain situation, such as inflammation (Pédron and Sansonetti 2008), and be the cause of infections when the host resistance mechanisms fail as a result of the ageing process. Antibiotic treatment, hospitalisation and CDAD are known to promote the increase of enterobacteria in the microbiota of elderly people (Hopkins et al. 2001; Bartosch et al. 2004; Woodmansey et al. 2004).

As for the health-promoting bacteria, the decrease of bifidobacteria in the gut microbiota, both in terms of abundance and species diversity, has been a commonly accepted ageing effect in the past years (Mitsuoka 1992; Gavini et al. 2001; Hopkins and Macfarlane 2002; Woodmansey et al. 2004; Mueller et al. 2006), magnified by antibiotic treatment, hospitalisation and CDAD (Hopkins et al. 2001; Bartosch et al. 2004; Zwielehner et al. 2009). However, several recent studies based on molecular techniques do not seem to confirm this: Rajilic-Stojanovic et al. (2009) did not find any difference between the bifidobacteria abundance in healthy elderly and young adults, nor did Biagi et al. (2010), who reported a significant decrease in the bifidobacterial population only in extremely old people. Lahtinen et al. (2009), in a study on elderly nursing home residents, also pointed out that the average level and species diversity of Bifidobacterium in elderly was higher than expected. The discrepancies in the Bifidobacterium behaviour with respect to the ageing process may be explained, again, by country-related differences, but also considering the remarkable temporal instability of the Actinobacteria (the phylum which includes the Bifidobacterium genus) population in the faecal microbiota of the elderly, highlighted by Rajilic-Stojanovic et al. (2009) and Claesson et al. (2010).

Recent developing and open questions

A substantial improvement in understanding how the ageing process affects the composition of the gut microbiota has been recently provided by Biagi et al. (2010) and Claesson et al. (2010), thanks to several unique characteristics of their studies. The uniqueness of the study of Biagi et al. resides in the recruitment procedure: Three Italian populations—instead of two—of Italian subjects, with very narrow ranges of age, were enrolled: 21 centenarians (aged 99–104 years), 22 elderly (aged 63–76 years) and 20 young adults (aged 25–40 years). The presence of the group of exceptionally old individuals allowed the authors to point out an unexpected similarity between the faecal microbiota of young and elderly adults, whereas only centenarians showed a markedly altered microbial ecosystem. Briefly, the gut microbiota of centenarians, analysed by using the human intestinal tract chip (HITChip; Rajilic-Stojanovic et al. 2009), was found to be enriched in facultative anaerobes, belonging to the genera Bacillus, Streptococcus and several members of the enterobacteria, whereas members of the Clostridium cluster XIVa and the F. prausnitzii group significantly decreased, approximately confirming most of the results reported by Mueller et al. (2006) for the Italian subsample, with the exception of the decrease in the Bacteroidetes abundance. The lack of significant differences between the gut ecosystems of young adults and elderly in their seventies may be due to the narrower range of age used by Biagi et al. during the recruitment. The 39 Italian elderly recruited by Mueller and coworkers were aged 61–100 years, whereas in the study of Biagi et al., two separate age groups were defined in the same interval, allowing a better resolution. These observations lead to the hypothesis that an average age of 70 years old may not be ‘old enough’ to be considered ‘elderly’ when we are analysing the gut environment, at least for the Italian population. A possible explanation may reside in the fact that the gut microbiota is known to be characterised by an astonishing resilience during adult life: Drugs treatment, travelling, dietary changes and so on are able to alter the balance of the gut microbiota, but the lasting consequences of these fluctuations are believed to be minimal. The ability of the gut microbial ecosystem to maintain and/or recover its balanced structure after an environmental perturbation may be greater than expected. Consequently, the age-related changes in physiology, lifestyle and nutrition may need time to permanently affect the gut microbiota. So, an interesting question that still needs to be answered (Table 1) is how changes in lifestyle can result in a permanently altered gut microbiota? And assuming that the age-related changes in the microbiota composition are progressive, when do they become evident enough to be sensed by the available characterisation techniques? The results presented by Biagi et al. seem to highlight that a healthy gut microbiota starts to be evidently affected by the age-related physiological and behavioural changes later than the age of 65, which is the usual ‘threshold age’ to be defined as elderly. However, these questions point out the lack of longitudinal studies in this field: Monitoring the changes in composition of the gut microbiota of the same subject over several, crucial years of his life (e.g. 60–80 years) may be the only way to answer these questions, thereby removing confounding effects of inter-individual variability.

Furthermore, the definition of ‘elderly’ itself may need to be revised, or better clarified, especially for what concerns the progressive ageing of the human population in Western countries. An increasing share of the elderly population is composed of ‘very old’ people, aged >85 years, i.e. ‘the oldest old group’ by Christensen et al. (2009). Moreover, the number of ‘extremely old’ people, i.e. centenarians, in industrialized countries has augmented about 20 times in the last 50 years (Roush 1996; Troen 2003). Centenarians, who represents the extreme limit of the human lifespan, are known to have unusual features for which most of the current concepts in biology and genetics are inadequate (De Benedictis and Franceschi 2006) and, as such, cannot be considered simply ‘elderly’ and grouped together with ‘younger elderly’ (65–70 years old people) when we are analysing age-related phenomena.

Lastly, it should not be surprising that the differences found by Biagi et al. between the gut microbiota of centenarians and younger people approximately reflect those reported between elderly with high and low frailty score (van Tongeren et al. 2005), since the centenarians are obviously very frail. This highlights the importance of carefully characterising several health parameters, such as the frailty score, of subjects involved in comparative studies focused on the ageing process.

Immediately after the study of Biagi et al., another remarkable paper was published on the topic by Claesson et al. (2010). This study involved a very large number (161) of Irish elderly subjects, aged 65–96 years. Their faecal microbiota was characterised by using the state-of-art of the molecular techniques, the pyrosequencing, and compared to that of nine younger adults (aged 28–46 years). Therefore, it represents the largest and most intense analysis of the elderly gut microbiota available to date. Unexpectedly, Bacteroidetes seemed to dominate the gut microbiota of the elderly, instead of the Firmicutes. Such strong modification in the asset of the gut microbiota structure was never reported before for elderly enrolled in other countries.

With the two most recent studies published in this field (Biagi et al. 2010; Claesson et al. 2010), the country specificity pointed out by Mueller et al. (2006) several years ago has emerged as even more striking. For instance, the gut microbiota of the Irish population seems to be characterised by a higher proportion of Bacteroidetes than that of Italian people. In the case of Irish people, this proportion increases with the ageing process (from 41% to 57%, in average), whereas in Italian elderly and centenarians, the proportion of Bacteroidetes remains approximately constant (Biagi et al. 2010) or even decreases (Mueller et al. 2006). It is worth pointing out that the differences between the results reported in these studies cannot be attributed to the different molecular approaches, since HITChip and pyrosequencing profiles have been already shown to be comparable (Claesson et al. 2009). In addition, both HITChip and pyrosequencing studies were in agreement, reporting a higher inter-individual variability in the microbiota profiles of older people.

The country specificity of age-related changes in the gut microbiota composition and the country-related differences in the gut microbiota itself are interesting findings, likely to be explored further in the next few years. With the aid of the newest molecular techniques, studies in gut ecology will probably determine how and to what extent lifestyle, nutrition, climatic differences, environmental exposure and so on can impact on the structure of the gut microbiota and its response to physiological and behavioural changes such as those which accompany the ageing process.

Gut microbiota, immunosenescence and inflamm-aging

The gut microbiota lives in close proximity to the gut mucosal surface. This high microbial load on the single cell epithelial layer undoubtedly represents a persistent threat of microbial invasion. In order to cope with this risk, humans evolved a specific gastrointestinal IS engineered to limit tissue invasion by intestinal microorganisms and to preserve the symbiotic nature of this interaction (Hooper and Macpherson 2010). The human gut-associated lymphoid tissue maintains the intestinal microbiota under control by a ‘constitutive low-grade physiological inflammation’ which is based on a web of positive and negative biological feedback processes. The peculiar biological architecture of the gastrointestinal mucosal IS permits the distinction between harmful pathogens and symbiotic microorganisms, generating a strong effector response towards the former and remaining tolerant to the latter. However, non-infectious human diseases characterised by an aberrant intestinal inflammation, such as allergies, inflammatory bowel diseases, metabolic syndrome, as well as genetic defect in enterocytes pattern recognition receptors system, can cause a breakdown in the homeostatic equilibrium between the intestinal microbiota and the host. Inflammation shifts the balance between protective symbionts and opportunistic pathogens (pathobionts) in favour of the latter (Sansonetti 2011).

In old people, the IS functionality declines as a result of a process known as ‘immunosenescence’ (Ostan et al. 2008; Shanley et al. 2009), and a chronic, low-grade inflammatory status, called ‘inflamm-aging’, characterises the whole ageing organism (Franceschi 2007; Franceschi et al. 2007; Larbi et al. 2008). Since the inflamm-aging also ends up in a localised, persistent inflammation at the level of the intestinal mucosa which can contribute to the systemic inflammation, it is important to understand how this process affects and/or is affected by the gut bacterial inhabitants. In fact, it has been postulated that the inflammatory process could be caused and/or nurtured by an abnormally activated immune response to the components of the gut microbiota, which may be due either to a diminished mucosal tolerance, or to the age-related changes in the gut microbiota composition, or both (Guigoz et al. 2008). Nutritional deficiency and age-associated tissue weakness and injuries may also contribute to trigger a pathogenic inflammatory response in the presence of normally harmless symbiotic bacteria (Schiffrin et al. 2009a). Moreover, pathobionts may take advantage of the decline in IS reactivity and inflammatory status to overgrow and nurture the inflammation process in a sort of self-sustained loop. It is also possible that the reduced bacterial excretion, due to the slower intestinal transit, faecal impaction and constipation, may result in an excessive ‘bacterial load challenge’, which is known to be a critical determinant for the production of several interleukins during inflammatory response (Maloy 2008).

It may be hypothesised that the maintenance of a ‘healthy’ gut microbiota structure during ageing could help in delaying or preventing the inflamm-aging process. In fact, several gut bacterial species (belonging to the genera Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus) are known to be able to downregulate the pro-inflammatory response at the level of the gut epithelium (Tien et al. 2006; Sokol et al. 2008; Heuvelin et al. 2009; Van Baarlen et al. 2009), or, as in the case of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, to indirectly prevent the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes (Kelly et al. 2004). Ouwehand et al. (2008) demonstrated that the amount of several autochthonous Bifidobacterium species in the gut microbiota of elderly subjects is negatively correlated with serum levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and the regulatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10), indicating that modulation of the faecal bifidobacterial population may represent a mean for reducing the inflammatory response.

Biagi et al. (2010) provided a deeper view of the correlation between the gut microbiota composition and the levels of several serum inflammatory markers. In their model of an extremely aged and consequently compromised microbiota, a rearrangement was observed in the population of butyrate producers and other bacteria with anti-inflammatory properties, such as F. prausnitzii. The resulting dysbiosis may be among the causes—or the results—of the proliferation of opportunistic enterobacteria, which seemed to be positively correlated to an increase in some pro-inflammatory signals (IL-6 and IL-8). The authors hypothesised that the age-related proliferation of pathobionts could either contribute to inflamm-aging or be promoted by the systemic inflammatory status.

In spite of these recent findings, a direct involvement of the autochthonous gut microbiota in the inflamm-aging process has yet to be determined, since it is not possible to understand if the observed differences between the gut microbiota of older and younger adults are either a consequence of the inflammatory status, or among its causes. However, it has been recently proposed that the age-associated increase in the intestinal abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and other gram-negative bacteria may result in an increased endotoxin challenge for the weakened intestinal barrier, ending up in an increased stimulation of the inflammatory response (Schiffrin et al. 2009a).

From observation to action: probiotics and prebiotics

The increased understanding of the impact of the gut microbiota on human health has resulted in attempts to manipulate its composition by the use of probiotics and prebiotics, both in prophylactic and therapeutic perspectives. Probiotics are defined as living microorganisms that provide a health benefit to the host when ingested in adequate amounts (FAO/WHO 2001). Effectiveness, safety and ability to pass through the upper gastrointestinal tract unaffected by bile acids and proteolytic enzymes are prerequisites for microorganisms to be considered probiotics. The most employed probiotics belong to the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, but other genera, including Escherichia, Enterococcus, Bacillus and Saccharomyces, are also commonly used, based on documented efficacy through clinical studies (Gibson et al. 2004). Their main beneficial effects are those provided by a non-compromised, healthy gut microbiota: the competition with pathogens for the adhesion to the gut epithelium, the production of substances that inhibit the growth of potentially harmful bacteria (i.e. organic acids, bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide), the synthesis of water soluble vitamins and the modulation of the immune processes (Chermesh and Eliakim 2006; Macfarlane et al. 2007; Park and Floch 2007; Neish 2009).

Prebiotics are chemical substances, usually oligosaccharides, acting as substrates specifically for the host’s autochthonous probiotic bacteria and thus promoting their growth (Gibson and Roberfoid 1995). Prebiotics are selected as being non-digestible by the host and non-metabolizable by non-probiotic gut bacteria (Gibson et al. 2004). The most common prebiotics are inulin, its fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) derivatives and galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), but other complex saccharides and fibres have been recently presented as candidate prebiotics (Candela et al. 2010). Because of their safety and stability, FOS and GOS are being increasingly used in Western diet, being incorporated into a wide range of commercial products, from bakery to dairy, as well as in infant- and animal-specific foods (Macfarlane et al. 2007). One of the most important beneficial activities of prebiotics, aside from the bifidogenic effect, is to act as substrate for fermentative processes whose end products are SCFAs. On the whole, pro/prebiotics have the potential of being helpful in the prevention and therapy of metabolic- and malnutrition-related conditions, as well as in a variety of pathological conditions, including inflammatory diseases and colon cancer (Candela et al. 2011).

Critical points in the modulation of the gut microbiota in elderly healthcare

Improving the level of health among older people can—and must—be one of the aims of modern gerontology, in order to decrease the rate of hospitalisation, the administration of drugs and, consequently, the healthcare cost of the ageing population. A healthier nutrition is one of the first strategies that can be employed to preserve health during ageing. The development of ‘elderly specific’ functional foods, containing probiotics and/or prebiotics, may help in preventing the disruption of the gut environment. Moreover, since older people are the most prominent users of antibiotics because of their increased susceptibility to infections, the administration of probiotics and prebiotics during/after drug treatments may be particularly important, in order to preserve/restore homeostasis between microbiota and the gut IS and prevent the occurrence of antibiotic-associated GI disturbances.

Evidence of the decline of bifidobacteria and other health-promoting bacteria in the gut of ageing subjects opens up the possibility of reversing such a trend by administration of probiotics, prebiotics or synbiotics (a mixture of prebiotics and one or more probiotic strains). It has been demonstrated that supplementation of probiotic Bifidobacterium strains significantly increases the levels of health-promoting bacteria in the faecal microbiota of elderly (Amhed et al. 2007; Lahtinen et al. 2009; Matsumoto et al. 2009). FOS and GOS ingestion, as well as symbiotic preparations, were reported to significantly increase the numbers of bifidobacteria at the expense of less beneficial groups in elderly individuals (Guigoz et al. 2002; Bartosch et al. 2005; Bouhnik et al. 2007; Vulevic et al. 2008). However, the administration of functional preparations needs to be underpinned by evidence of a true therapeutic effect (e.g. alleviate constipation or diarrhoea) reported by the enrolled patients, not just to increase or decrease specific bacterial groups, in order for the change to be considered beneficial. Generating such evidence is a challenge, and it is even more difficult to ascertain the ability of pro/prebiotics to prevent age-related disturbances.

Nevertheless, probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics are commonly believed to be useful (or hold potential promise) in promoting certain aspects of health in elderly people (Tiihonen et al. 2010). In the sections below, the most relevant results regarding the use of functional preparations in several common age-related conditions will be discussed.

Pro/prebiotics and constipation

Pro/prebiotics are believed to have therapeutic potential for the treatment of constipation, principally because of their normalizing effect on the gut microbiota structure. The gut microbiota of chronically constipated people is believed to be different from the healthy situation, but whether the dysbiosis is either a secondary effect of constipation or a contributing cause is still an open question.

Clinical trials reporting evidence of the efficacy of probiotic administration in improving constipation in ageing people are very few and, again, barely comparable. All of them (Pitkala et al. 2007; Carlsson et al. 2009; An et al. 2010) involve elderly people living in nursing homes. Selection of these volunteers is justified by the higher incidence of constipation among ‘institutionalised’ elderly (Gallagher and O’Mahony 2009; Spinzi et al. 2009; An et al. 2010) and has the advantage of providing a highly homogeneous population with regard to nutritional habits and lifestyle, but this low variability does not reflect the situation of the free-living elderly population. Consequently, the findings from those trials should not be considered generally applicable. Moreover, only the study of Pitkala et al. (2007) was performed on a large number of subjects (n = 209) and reported the ability of two strains of Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium lactis to increase the frequency of bowel movements in institutionalised Finnish elderly. By comparison, the clinical trials undertaken by Carlsson et al. (2009) and An et al. (2010) involved 15 and 19 nursing home residents, respectively. The first was presented as a pilot study to evaluate the feasibility of a probiotic treatment on institutionalised aged people with dementia in Sweden, but the results obtained were not promising: Strains of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactococcus lactis were not able to produce detectable effects on constipation. Conversely, An et al. showed that a probiotic mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Pediococcus pentosaceus and B. longum was able to significantly improve frequency of defecation, state and amount of stool, in Korean nursing home residents.

It is quite clear that these studies are too few and involve too few subjects; even if the results of Pitkala et al. (2007) and An et al. (2010) were statistically significant, the conclusions should be interpreted with great caution. As for the prebiotics, only one study has been published evaluating the effect of inulin and lactose specifically on the bowel habits of elderly constipated people (Kleessen et al. 1997). The results of this clinical trial were promising: The ingestion of inulin improved constipation in nine out of ten subjects, with only mild discomfort (flatulence). More recently, Ouwehand et al. (2009) reported a slight increase in stool frequency in healthy elderly taking a synbiotic preparation (lactitol and L. acidophilus NCFM), but the efficacy of this synbiotic preparation was not tested on constipated people.

The effect of pro/prebiotics on functional constipation is still to be demonstrated for both paediatric and adult population (Chmielewska and Szajewska 2010). In the case of the elderly population, the need for studies involving high number of chronically constipated subjects is even more evident.

Pro/prebiotics and C. difficile-associated diarrhoea

The disruption of the gut microbiota balance, which occurs through the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, is believed to be responsible for the increased susceptibility to CDAD (Hopkins and Macfarlane 2002; Pultz and Donskey 2005; Chang et al. 2008). Given the inhibitory effect of a healthy gut microbiota on C. difficile overgrowth and toxin release, the active reconstitution of a ‘normal’ microbiota is theoretically attractive, and the use of probiotics to prevent/treat CDAD is gaining a considerable interest (Leffler and Lamont 2009; Parkes et al. 2009). Many health-promoting strains, belonging to the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Saccharomyces, have been tested on human adults. Even if the results seem promising for what concerns the prophylactic use of probiotics (McFarland 2006), the evidence suggested that probiotics may be able to provide modest or no benefit in the therapy of CDAD (Pillai and Nelson 2008). As for the elderly, the possibility to use pro/prebiotics in the prevention of CDAD is still in its infancy: Only Hickson et al. (2007) reported a reduction in CDAD incidence and an absence of C. difficile toxin in the faeces of elderly treated with Lactobacillus casei.

Another possibility in the treatment of CDAD is the reconstitution of a healthy gut microbiota through stool transplantation from a healthy donor. In spite of the hypothetical danger to spread pathogenic bacteria from the donor to the patient, there is growing interest in this approach resulting from its documented efficacy on both recurrent (Persky and Brandt 2000) and acute (You et al. 2008) CDAD. The use of this technique on older patients is not very well reported (Rubin et al. 2009), but its low cost and efficiency may call for future research focused on this specific population which represents a growing sector of the healthcare cost in Western countries.

Pro/prebiotics and the functionality of the immune system

Immunostimulatory properties, such as modulation of cytokines production or adjuvant effects on T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells activity, have been demonstrated for various health-promoting Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains (Meydani and Ha 2000; Blum et al. 2002). A complete analysis of the in vivo studies demonstrating immunomodulatory effects of pro/prebiotics on human subjects is far beyond the aim of this review and has been addressed elsewhere (Nova et al. 2007; Lomax and Calder 2009), but it seems that pro/prebiotics have the potentiality to enhance the immune response and modify some inflammatory conditions (Saulnier et al. 2009; Antoine 2010). In the elderly, probiotics and prebiotics have been suggested as having the potential to restore immune functions (Candore et al. 2008) and, consequently, to help in preventing and/or limiting the effects of immunosenescence.

Earlier studies showed that 3- and 6-week interventions with B. lactis can have positive effects on the IS of old people, such as increases of NK cells tumouricidal activity and monocytes phagocytic capacity (Chiang et al. 2000; Arunachalam et al. 2000; Gills et al. 2001a, b). Similar results were also described following supplementation of L. rhamnosus (Sheih et al. 2001) and L. casei Shirota (Takeda and Okumura 2007).

A study focused on a particular population of hospitalised, enterally fed elderly demonstrated that the level of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α decreased in response to supplementation of fermented milk containing a probiotic strain of Lactobacillus; the elderly volunteers also showed a decline in the incidence of infections (Fukoshima et al. 2007). A probiotic yogurt supplementation was also tested on elderly affected by intestinal bacterial overgrowth and was able to normalise the response to endotoxin and modulate inflammatory markers in blood phagocytes (Schiffrin et al. 2009b).

Supplementation of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains was also positively correlated with the spermine and spermidine levels, which has been suggested to be associated with reduced inflammation (Matsumoto and Benno 2006). Most recently, Ibrahim et al. (2010) demonstrated that a commercial probiotic cheese containing L. rhamnosus and L. acidophilus was able to improve NK cells ability to kill target tumour cells and the phagocytosis activity of granulocytes and monocytes.

Significant increase of phagocytosis, NK cell activity and production of the regulatory cytocine IL-10 were also reported following FOS and GOS supplementation in elderly volunteers, together with a reduction in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α; Guigoz et al. 2002; Schiffrin et al. 2007; Vulevic et al. 2008).

As for the effects of synbiotic preparations, results are still preliminary. Ouwehand et al. (2009) reported an improved mucosal integrity, evaluated as increased faecal levels of spermidine and other intestinal immune markers, following the administration of L. acidophilus and lactitol.

Most of the results summarized above were obtained in studies involving subjects with a great variability in nationality and range of age. Confirmation of the results, as well as more insights in the cross talk between gut microbiota and IS, are needed, especially in the perspective of the development of nutritional strategies targeting the mucosal-host reactivity. Moreover, even if some of the results seem promising, parameters need to be established to evaluate the practical significance of the effects of pro/prebiotic treatments on the IS.

An interesting decrease in the duration, but not in the incidence, of respiratory and gastrointestinal ‘winter infections’ in 360 free-living elderly was reported following a 3-week L. casei supplementation (Turchet et al. 2003). This trend was recently confirmed in a larger (1,072 elderly volunteers), multicentric, double-blind, controlled trial using the same probiotic species (Guillermard et al. 2010). Since ‘common’ infectious diseases, such as respiratory tract infections, flu and flu-like syndromes, acute otitis and sinusitis and gastroenteritis, are more frequent and severe in the ageing population, remaining a considerable cause for morbidity and mortality (Gavazzi and Krause 2002), these results may be of interest: Reducing the duration of infections of 1 or 2 days may not appear important in terms of individual health, but if the cost of 1 day of hospitalisation is considered the community benefit becomes clear (Antoine 2010). Moreover, Boge et al. (2009) showed that in two clinical trials, performed on 86 and 222 elderly subjects, the consumption of a probiotic drink containing L. casei for several weeks before and after flu vaccination was correlated to a significant increase in the influenza-specific antibody titre. This seems to demonstrate the potential of probiotics to be helpful also in improving the clinical protective efficacy of flu vaccine in the elderly population, in which it is usually considerably reduced (Goodwin et al. 2006).

Concluding remarks

Ageing presents a major nutritional challenge, not only in relation to the dietary supply of certain nutrients but also their metabolism. Physiological and other age-related changes may lead to inadequate nutrition unless diets are modified to improve the nutrient density and to incorporate food constituents that maintain optimal nutrient status and promote health. Micronutrient deficiencies, which are not uncommon in the elderly, are associated with a decline in body function which can lead to a higher risk of infections and chronic disease. Low-grade inflammation is hypothesised to be central to the pathogenesis of several chronic diseases (van Ommen et al. 2008), and although multiple micronutrient supplements have been reported to reduce the inflammatory status associated with obesity (Bakker et al. 2010), the effect on age-related inflammation requires investigation. Many studies demonstrated that the dynamics involved in the ageing process of the human metaorganism implies a strong modulation in its microbial counterpart. Establishing a vicious circle, the aged-type microbiota contributes to the pathophysiological process of ageing affecting nutrition, inflammatory status and susceptibility to infection. However, our knowledge of the gut microbiota composition of elderly people is still far from complete.

We propose a general and preliminary model of the dynamics of the intestinal microbiota with ageing (Fig. 2). According to this model, the ageing process of the human intestinal microbiota implies a substantial reduction of its microbial biodiversity, driving towards an aged-type microbial ecosystem that resembles the infant-type microbiota. In fact, both the infant-type and the aged-type are characterised by lower biodiversity, higher abundance of opportunistic environmental aerobes and fewer symbiont anaerobes. However, even if they are comparable in terms of biodiversity, the aged- and infant-type microbiota live in completely different gastrointestinal habitat, and the functional outcome of the microbiota–host interaction is absolutely different. Whereas the threshold for the transition from infant-type to adult-type is defined by weaning, the ageing process shows a striking subject specificity. In fact, ageing-associated modifications of the gut microbiota depend on individual-specific characteristics such as diet and nationality, which can dramatically impact on the microecology of the human GI tract. For these reasons, future research will have to be carefully structured, especially during the recruitment procedure, providing detailed information on the nationality, age range and the health parameters of the participants, and molecular characterisation approaches will have to be used on a large number of subjects.

Every time a human baby is born, a rich and dynamic microbial ecosystem develops from a sterile environment. During the first year of life, until weaning, the gut ecosystem is prevalently colonized by opportunistic microorganisms to which a baby is exposed in its environment (Palmer et al. 2007). The earliest colonizers are often aerobes such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and Enterobacteria, followed by anaerobic later colonizers such as Eubacteria and Clostridia. After these earlier stages, it is generally though that the microbiota of breast-fed infants is largely dominated by Bifidobacterium. After weaning, the developmental changes in the gut mucosa and in the intestinal IS, together the introduction of a solid diet, drive to the transition to a resilience adult-like profile of the human gut microbiota, characterised by a remarkable microbial biodiversity. The ageing of the gut microbiota starts after a subject-specific ‘threshold age’ which depends on individual characteristics such as diet, country and, eventually, frailty. In any case, changes of diet, lifestyle and the immunosenescence of the intestinal IS dramatically impact the microbial ecology of the human GI tract. Symmetrically to what happens in the early stage of our life, the aged-type microbiota shows a low microbial biodiversity, and it is characterised by an increase in opportunistic environmental facultative aerobes Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, as well as a reduction in anaerobes, such as Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa and Bacteroidetes. However, differently from the infant-type microbiota, the aged type is characterised by a low abundance of Bifidobacterium

Even less is known about the involvement of the gut microbial ecosystem in the inflamm-aging process and in the decline in the functionality of the IS. It is possible that the ageing-associated inflammatory status may be amongst the causes of the changes occurring in the gut microbiota composition. At the same time, the compromised balance of the gut microbiota may nurture the inflammation, creating a self-sustaining cycle.

The administration of health-promoting bacteria and/or prebiotic fibres to elderly patients is reported to induce changes in several immune and inflammatory parameters, demonstrating that the manipulation of the gut microbiota may result in modification of the functionality of an aged IS. Even if the possibility of keeping immunosenescence and inflamm-aging under control by a simple supplementation and/or functional food is fascinating, the concept of ‘immunonutrition’ is still in its infancy and needs to be better related to the health, immunological and nutritional status of the considered elderly people, as well as their nationality and actual age. Moreover, the eventual ‘improvement’ in the immune and inflammatory status of elderly involved in feeding trials needs to be better defined, in terms of a true health advantage: Until now, only a shorter duration of common infectious diseases has been reported as a positive effect of a probiotic supplementation, but not a decrease in the infection incidence. Our critical analysis of the application of pro/prebiotics in distinctive intestinal conditions of elderly people (i.e. constipation and CDAD) also highlighted the fact that very limited clinical evidence is available for the efficacy of pro/prebiotics in the prevention and especially treatment of these disorders.

In conclusion, even if pro/prebiotics have the potential to become a useful support in the development of ‘personalized’ nutritional strategies to improve/preserve the health status of the ageing population, more carefully designed and controlled studies, with higher numbers of subjects, are needed to determine whether and under what conditions they can be truly helpful.

References

Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rockett HR, Sampson L, Rimm EB, Willett WC (1998) A prospective study of dietary fiber type and symptomatic diverticular disease in men. J Nutr 128:714–719

Allen LH (2008) Causes of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. Food Nutr Bull 29:S20–S34

Amhed M, Prased J, Gill H, Stevenson L, Gopal P (2007) Impact of consumption of different levels of Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 on the intestinal microflora of elderly human subjects. J Nutr Health Aging 11:26–31

An HM, Baek EH, Jang S, Lee DK, Kim MJ, Kim JR, Lee KO, Park JG, Ha NJ (2010) Efficacy of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) supplement in management of constipation among nursing home residents. Nutr J 9:5

Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Backhed F, Nyrén P, Engstrand L (2008) Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 3:e2836

Antoine JM (2010) Probiotics: beneficial factors of the defence system. Proc Nutr Soc 69:429–433

Armougom F, Raoult D (2008) Use of pyrosequencing and DNA barcodes to monitor variations in Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes communities in the gut microbiota of obese humans. BMC Genomics 9:576

Arunachalam K, Gills HS, Chandra RK (2000) Enhancement of natural immune function by dietary consumption of Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019). Eur J Clin Nutr 54:263–267

Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI (2005) Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 307:1915–1920

Bakker GC, van Erk MJ, Pellis L, Wopereis S, Rubingh CM, Cnubben NH, Kooistra T, van Ommen B, Hendriks HF (2010) An antiinflammatory dietary mix modulates inflammation and oxidative and metabolic stress in overweight men: a nutrigenomics approach. Am J Clin Nutr 91:1044–1059

Barbut F, Petit JC (2001) Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 7:405–410

Bartosch S, Fite A, Macfarlane GT, McMurdo MET (2004) Characterization of bacterial communities in feces from healthy elderly volunteers and hospitalized elderly patients by using real time PCR and effects of antibiotic treatment on the fecal microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3575–3581

Bartosch S, Woodmansey EJ, Paterson JCM, McMurdo MET, Macfarlane GT (2005) Microbiological effects of consuming a symbiotic containing Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis and oligofructose in elderly persons, determined by real time polymerase chain reaction and counting of viable bacteria. Clin Infect Dis 40:28–37

Biagi E, Nylund L, Candela M, Bucci L, Ostan R, Nikkila J, Monti D, Satokari R, Franceschi C, Brigidi P, de Vos WM (2010) Through ageing, and beyond: gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS ONE 5:e10667

Blum S, Haller D, Pfeifer A, Schiffrin EJ (2002) Probiotics and immune response. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 22:287–309

Boge T, Rémigy M, Vaudaine S, Tanguy J, Bourdet-Sicard R, van der Werf S (2009) A probiotic fermented diary drink improves antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly in two randomised controlled trials. Vaccine 27:5677–5684

Bouhnik Y, Achour L, Paineau D, Riottot M, Attar A, Bornet F (2007) Four-week short chain fructo-oligosaccharides ingestion leads to increasing fecal bifidobacteria and cholesterol excretion in healthy elderly volunteers. Nutr J 6:42

Candela M, Maccaferri S, Turroni S, Carnevali P, Brigidi P (2010) Functional intestinal microbiome, new frontiers in prebiotic design. Int J Food Microbiol 140:93–101

Candela M, Guidotti M, Fabbri A, Brigidi P, Franceschi C, Fiorentini C (2011) Human intestinal microbiota: cross-talk with the host and its potential role in colorectal cancer. Crit Rev Microbiol 37:1–14

Candore G, Balistreri CR, Colonna-Romano G, Grimaldi MP, Lio D, Listì F, Scola L, Vasto S, Caruso C (2008) Immunosenescence and anti-immunosenescence therapies: the case of probiotics. Rejuv Res 11:425–432

Carlsson M, Gustafson Y, Haglin L, Eriksson S (2009) The feasibility of serving liquid yoghurt supplemented with probiotic bacteria, Lactobacillus rhamnosus LB21 and Lactococcus lactis L1A—a pilot study among old people with dementia in a residential care facility. J Nutr Health Aging 13:813–819

Chang JY, Antonopoulos DA, Kalra A, Tonelli A, Khalife WT, Schmidt TM, Young WB (2008) Decreased diversity of fecal microbiome in recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Infect Dis 197:435–438

Chermesh I, Eliakim R (2006) Probiotics and the gastrointestinal tract: where are we in 2005? World J Gastroenterol 12:853–857

Chiang BL, Sheih YH, Wang LH, Lial CH, Gills HS (2000) Enhancing immunity by dietary consumption of a probiotic lactic acid bacterium (Bifidobacterium lactis HN019): optimization and definition of cellular immune responses. Eur J Clin Nutr 54:849–855

Chmielewska A, Szajewska H (2010) Systematic review of randomised controlled trials: probiotics for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol 16:69–75

Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW (2009) Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 374:1196–1208

Claesson MJ, O'Sullivan O, Wang Q, Nikkila J, Marchesi JR, Smidt H, de Vos WM, Paul Ross R, O'Toole PW (2009) Comparative analysis of pyrosequencing and a phylogenetic microarray for exploring microbial community structures in the human distal intestine. PLoS ONE 4:e6669

Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O'Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, de Weerd H, Flannery E et al. (2010) Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000097107

Cober ED, Malani PN (2009) Clostridium difficile infections in the “oldest” old: clinical outcomes in patients aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:659–662

Cohen JE (2003) Human population: the next half century. Science 302:1172–1175

Comparato G, Pilotto A, Franzè A, Franceschi M, Di Mario F (2007) Diverticular disease in the elderly. Dig Dis 25:151–159

Cummings JH (1995) Short chain fatty acids. In: Gibson GR, Macfarlane GT (eds) Human colonic bacteria: role in nutrition, physiology and health. CRC, Boca Raton

Cust AE, Skilton MR, van Bakel MM, Halkjaer J, Olsen A, Agnoli C, Psaltopoulou T, Buurma E, Sonestedt E, Chirlaque MD, Rinaldi S, Tjønneland A, Jensen MK, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Kaaks R, Nöthlings U, Chloptsios Y, Zylis D, Mattiello A, Caini S, Ocké MC, van der Schouw YT, Skeie G, Parr CL, Molina-Montes E, Manjer J, Johansson I, McTaggart A, Key TJ, Bingham S, Riboli E, Slimani N (2009) Total dietary carbohydrate, sugar, starch and fibre intakes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr 63:S37–S60

Dahl WJ, Whiting SJ, Healey A, Zello GA, Hilderbrandt SL (2003) Increased stool frequency occurs when finely processed pea hull fiber is added to usual foods consumed by elderly residents in long-term care. J Am Diet Assoc 103:1199–1202

Dali-Youcef N, Andrès E (2009) An update on cobalamin deficiency in adults. QJ Med 102:17–28

De Benedictis G, Franceschi C (2006) The unusual genetics of human longevity. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 10:pe20

de Groot LC, Verheijden MW, de Henauw S, Schroll M, van Staveren WA, SENECA Investigators (2004) Lifestyle, nutritional status, health, and mortality in elderly people across Europe: a review of the longitudinal results of the SENECA study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59:1277–1284

Dean M, Raats MM, Grunert KG, Lumbers M, Food in Later Life Team (2009) Factors influencing eating a varied diet in old age. Public Health Nutr 12:2421–2427

den Elzen WP, Groeneveld Y, de Ruijter W, Souverijn JH, le Cessie S, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J (2008) Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors and vitamin B12 status in elderly individuals. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27:491–497

Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Reiman D (2008) The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol 6:e280

Dixon T, Mitchell P, Beringer T, Gallacher S, Moniz C, Patel S, Pearson G, Ryan P (2006) An overview of the prevalence of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D inadequacy amongst elderly patients with or without fragility fracture in the United Kingdom. Curr Med Res Opin 22:405–415

Doty RL, Shaman P, Applebaum SL, Giberson R, Siksorski L, Rosenberg L (1984) Smell identification ability: changes with age. Science 226:1441–1443

Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman DA (2005) Diversity of the human intestinal flora. Science 308:1635–1638

Ervin RB (2008) Healthy Eating Index scores among adults, 60 years of age and over, by sociodemographic and health characteristics: United States, 1999–(2002). Adv Data 395:1–16

FAO/WHO (2001) Evaluation of health and nutritional properties of powder milk and live lactic acid bacteria. ftp://ftp.fao.org/es/esn/food/probio_report_en.pdf

Fernández-Bañares F, Monzón H, Forné M (2009) A short review of malabsorption and anemia. World J Gastroenterol 15:4644–4652

Finch S, Doyle W, Lowe C, Bates CJ, Prentice A, Smithers G, Clarke PC (1998) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: people aged 65 years and over. The Stationery Office, London

Flint HJ, Duncan SH, Scott KP, Louis P (2007) Interactions and competition within the microbial community of the human colon: links between diet and health. Environ Microbiol 9:1101–1111

Franceschi C (2007) Inflammaging as a major characteristic of old people: can it be prevented or cured? Nutr Rev 65:S173–S176

Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, Panourgia MP, Invidia L, Celani L, Scurti M, Cevenini E, Castellani GC, Salvioli S (2007) Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev 128:92–105

Frank DN, St. Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR (2007) Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:13780–13785

Fukoshima Y, Miyaguchi S, Yamano T, Kaburagi T, Iino H, Ushida K, Sato K (2007) Improvement of nutritional status and incidence of infections in hospitalised, enterally fed elderly by feeding of fermented milk containing probiotic Lactobacillus johnsonii La1 (NCC533). Br J Nutr 98:969–977

Gallagher P, O'Mahony D (2009) Constipation in old age. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 23:875–887

Gavazzi G, Krause KH (2002) Ageing and infections. Lancet Infect Dis 2:659–666

Gavini F, Cayuela C, Antoine JM, Lecoq C, Le Fabure B, Membré JM, Neut C (2001) Differences in distribution of bifidobacterial and enterobacterial species in human fecal microflora of three different (children, adults, elderly) age groups. Microb Ecol Health Dis 13:40–45

Genser D (2008) Food and drug interaction: consequences for the nutrition/health status. Ann Nutr Metab 52:29–32

Gibson GR, Roberfoid MB (1995) Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr 125:1401–1412

Gibson GR, Probert HM, Loo JV, Rastall RA, Roberfroid MB (2004) Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: updating the concept of prebiotics. Nutr Res Rev 17:259–275

Gill SR, Pop M, DeBoy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, Gordon JI, Relman DA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Nelson KE (2006) Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 312:1355–1359

Gills HS, Rutherfurd KJ, Cross ML (2001a) Dietary probiotic supplementation enhances natural killer cells activity in the elderly: an investigation of age-related immunological changes. J Clin Immunol 21:264–271

Gills HS, Rutherfurd KJ, Cross ML, Gopal PK (2001b) Enhancement of immunity in the elderly by dietary supplementation with the probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis HN019. Am J Clin Nutr 74:833–839

Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L (2006) Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine 24:1159–1169

Guigoz Y, Rochat F, Perruisseau-Carrier G, Rochat I, Schiffrin J (2002) Effects of oligosaccharide on the fecal flora and non-specific immune system in elderly people. Nutr Res 22:13–25

Guigoz Y, Doré J, Schiffrin J (2008) The inflammatory status of old age can be nurtured from the intestinal environment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 11:13–20

Guillermard E, Tondu F, Lacoin F, Schrezenmeir J (2010) Consumption of a fermented diary product containing the probiotic Lactobacillus casei DN-114001 reduces the duration of respiratory infections in the elderly in a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr 103:58–68

Harris DG, Davies C, Ward H, Haboubi NY (2008) An observational study of screening for malnutrition in elderly people living in sheltered accommodation. J Hum Nutr Diet 21:3–9

Hattori M, Taylor TD (2009) The human intestinal microbiome: a new frontier of human biology. DNA Res 16:1–12

Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Kitahara M, Benno Y (2003) Molecular analysis of fecal microbiota in elderly individuals using 16S rDNA library and T-RFLP. Microbiol Immunol 47:557–570

Henry HL, Bouillon R, Norman AW, Gallagher JC, Lips P, Heaney RP, Vieth R, Pettifor JM, Dawson-Hughes B, Lamberg-Allardt CJ, Ebeling PR (2010) 14th Vitamin D Workshop consensus on vitamin D nutritional guidelines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 121:4–6

Heuvelin E, Lebreton C, Grangette C, Pot B, Cerf-Bensussan N, Heyman M (2009) Mechanisms involved in alleviation of intestinal inflammation by Bifidobacterium breve soluble factors. PLoS ONE 4:e5184

Hickson M, D’Souza AL, Muthu N, Rogers TR, Want S, Rajkumar C, Bulpitt CJ (2007) Use of probiotic Lactobacillus preparation to prevent diarrhoea associated with antibiotics: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 335:80–83

Hooper LV, Midtvedt T, Gordon JI (2002) How host microbial interactions shape the nutrient environment of the mammalian intestine. Ann Rev Nutr 22:283–307

Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ (2010) Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol 10:159–169

Hopkins MJ, Sharp R, Macfarlane GT (2001) Age and disease related changes in intestinal bacterial populations assessed by cell culture, 16S rRNA abundance, and community cellular fatty acid profiles. Gut 48:198–205

Hopkins MJ, Macfarlane GT (2002) Changes in predominant bacterial populations in human feces with age and with Clostridium difficile infection. J Med Microbiol 51:448–454

Ibrahim F, Ruvio S, Granlund L, Salminen S, Viitanen M, Ouwehand AC (2010) Probiotics and immunosenescence: cheese as a carrier. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 59:53–59

Kelly D, Campbell JI, King TP, Grant G, Jansson EA, Coutts AG, Pettersson S, Conway S (2004) Commensal anaerobic gut bacteria attenuate inflammation by regulating nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of PPAR-gamma. Nat Immunol 5:104–112

Kelly CP (2009) A 76-years old man with recurrent Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea: review of C difficile infection. JAMA 3010:954–962

Kharicha K, Iliffe S, Harari D, Swift C, Gillmann G, Stuck AE (2007) Health risk appraisal in older people 1: are older people living alone an “at-risk” group? Br J Gen Pract 57:271–276

Kleessen B, Sycura B, Zunft HJ, Blaut M (1997) Affects of inulin and lactose on fecal microflora, microbial activity and bowel habits in elderly constipated persons. Am J Clin Nutr 65:1397–1402

Koehler J, Leonhaeuser I-U (2008) Changes in food preferences during aging. Ann Nutr Metab 52:15–19

Lahtinen SJ, Tammela L, Korpela J, Parhiala R, Ahokoski H, Mykkanen H, Salminen S (2009) Probiotics modulate the Bifidobacterium microbiota of elderly nursing home residents. Age 31:59–66

Larbi A, Franceschi C, Mazzatti D, Solana R, Wikby A, Pawelec G (2008) Aging of the immune system as a prognostic factor of human longevity. Physiology 23:64–74

Lay C, Rigottier-Gois L, Holmstrøm K, Rajilic M, Vaughan EE, de Vos WM, Collins MD, Thiel R, Namsolleck P, Blaut M, Doré J (2005) Colonic microbiota signatures across five northern European countries. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4153–4155

Leffler DA, Lamont JT (2009) Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Gastroenterology 136:1899–1912

Leser TD, Molbak L (2009) Better living through microbial action: the benefits of the mammalian gastrointestinal microbiota on the host. Environ Microbiol 11:2194–2206

Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI (2006a) Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell 124:837–848

Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI (2006b) Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444:1022–1023

Lomax AR, Calder PC (2009) Prebiotics, immune function, infection and inflammation: a review of the evidence. Br J Nutr 101:633–658

Macfarlane GT, Steed H, Macfarlane S (2007) Bacterial metabolism and health-related effects of galacto-oligosaccharides and other prebiotics. J Appl Microbiol 104:305–344

Mahowald MA, Rey FE, Seedorf H, Turnbaugh PJ, Fulton RS, Wollam A, Shah N, Wang C, Magrini V, Wilson RK, Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B, Crock LW, Russell A, Verberkmoes NC, Hettich RL, Gordon JI (2009) Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:5859–5864

Mäkivuokko H, Tiihonen K, Tynkkynen S, Paulin L, Rautonen N (2010) The effect of age and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on human intestinal microbiota composition. Br J Nutr 103:227–234

Maloy KJ (2008) The interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis in intestinal inflammation. J Intern Med 263:584–590

Mariat D, Firmesse O, Levenez F, Guimaraes VD, Sokol H, Doré J, Corthier G, Furet JP (2009) The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol 9:123

Matsumoto M, Benno Y (2006) Anti-inflammatory metabolite production in the gut from the consumption of probiotic yogurt containing Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis LKM512. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 70:1287–1292

Matsumoto M, Sakamoto M, Benno Y (2009) Dynamics of fecal microbiota in hospitalized elderly fed prebiotic LKM512 yogurt. Microbiol Immunol 53:421–432

McFarland LV, Elmer GW, Surawicz CM (2002) Breaking the cycle: treatment strategies for 163 cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol 97:1769–1775

McFarland LV (2006) Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol 101:812–822

Meydani SN, Ha W-K (2000) Immunologic effects of yogurt. Am J Clin Nutr 71:861–872

Mitsuoka T (1992) Intestinal flora and ageing. Nutr Rev 50:438–446

Monaghan T, Boswell T, Mahida YR (2008) Recent advances in Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Gut 57:850–860

Mueller S, Saunier K, Hanisch C, Norin E, Alm L, Midtvedt T, Cresci A, Silvi S, Orpianesi C, Verdenelli MC, Clavel T, Koebnick C, Zunft HJF, Doré J, Blaut M (2006) Differences in fecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: a cross-sectional study. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:1027–1033

Neish AS (2009) Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology 136:65–80

Newton JP, Yemm R, Abel RW, Menhinick S (1993) Changes in human jaw muscles with age and dental state. Gerodontology 10:16–22

Nova E, Warnberg J, Gòmez-Martìnez S, Diaz LE, Romeo J, Marcos A (2007) Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in different stages of life. Br J Nutr 98:S90–S95

Orr WC, Chen CL (2002) Aging and neural control of the GI tract: IV. Clinical and physiological aspects of gastrointestinal motility and aging. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283:G1226–G1231

Ostan R, Bucci L, Capri M, Salvioli S, Scurti M, Pini E, Monti D, Franceschi F (2008) Immunosenescence and immunogenetics of human longevity. Neuroimmunomodulation 15:224–240

Ouwehand AC, Bergsma N, Parhiala R, Lahtinen S, Gueimonde M, Finne-Soveri H, Strandberg T, Pitkala K, Salminen S (2008) Bifidobacterium microbiota and parameters of immune function in elderly subjects. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 53:18–25

Ouwehand AC, Tiihonen K, Saarinen M, Putaala H, Rautonen N (2009) Influence of a combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and lactitol on healthy elderly: intestinal immune parameters. Br J Nutr 101:367–375

Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, Brown PO (2007) Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol 5:e177