Abstract

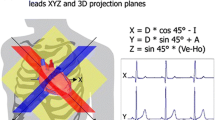

Cardiogoniometry (CGM), a spatiotemporal electrocardiologic 5-lead method with automated analysis, may be useful in primary healthcare for detecting coronary artery disease (CAD) at rest. Our aim was to systematically develop a stenosis-specific parameter set for global CAD detection. In 793 consecutively admitted patients with presumed non-acute CAD, CGM data were collected prior to elective coronary angiography and analyzed retrospectively. 658 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria, 405 had CAD verified by coronary angiography; the 253 patients with normal coronary angiograms served as the non-CAD controls. Study patients—matched for age, BMI, and gender—were angiographically assigned to 8 stenosis-specific CAD categories or to the controls. One CGM parameter possessing significance (P < .05) and the best diagnostic accuracy was matched to one CAD category. The area under the ROC curve was .80 (global CAD versus controls). A set containing 8 stenosis-specific CGM parameters described variability of R vectors and R-T angles, spatial position and potential distribution of R/T vectors, and ST/T segment alterations. Our parameter set systematically combines CAD categories into an algorithm that detects CAD globally. Prospective validation in clinical studies is ongoing.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL et al (1975) A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation 51:5–40

Chou TC, Helm RA, Kaplan S (1974) Clinical vectorcardiography, 2nd edn. Grune and Stratton, New York

Couderc JP, Zareba W, McNitt S et al (2007) Repolarization variability in the risk stratification of MADIT II patients. Europace 9(9):717–723

Davies SW (2001) Clinical presentation and diagnosis of coronary artery disease: stable angina. Br Med Bull 59:17–27

Drew BJ, Pelter MM, Lee E et al (2005) Designing prehospital ECG systems for acute coronary syndromes. Lessons learned from clinical trials involving 12-lead ST-segment monitoring. J Electrocardiol 38:180–185

Erikssen J, Müller C (1972) Comparison between scalar and corrected orthogonal electrocardiogram in diagnosis of acute myocardial infarcts. Br Heart J 34:81–86

Frank E (1956) An accurate, clinically practical system for spatial vectorcardiography. Circulation 13:737–749

Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT et al (2002) ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). Circulation 106(14):1883–1892

Gray W, Corbin M, King J et al (1972) Diagnostic value of vectorcardiogram in strictly posterior infarction. Br Heart 34:1163–1169

Hinrikus H, Suhhova A, Bachmann M et al (2009) Electroencephalographic spectral asymmetry index for detection of depression. Med Biol Eng Comput 47(12):1291–1299

Howard PF, Benchimol A, Desser KB et al (1976) Correlation of electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram with coronary occlusion and myocardial contraction abnormality. Am J Cardiol 38:582–587

Mazzadi AN, André-Fouët X, Costes N et al (2006) Mechanisms leading to reversible mechanical dysfunction in severe CAD: alternatives to myocardial stunning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291(6):H2570–H2582

McConahay DR, McCallister BD, Hallermann FJ et al (1970) Comparative quantitative analysis of the electrocardiogram and the vectorcardiogram. Correlations with the coronary arteriogram. Circulation 42:245–259

Mehta J, Hoffman I, Smedresman P et al (1976) Vectorcardiographic, electrocardiographic, and angiographic correlations in apparently isolated inferior wall myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 91:699–704

Murray RG, Lorimer AR, Dunn FG et al (1976) Comparison of 12-lead and computer-analysed 3 orthogonal lead electocardiogram in coronary artery disease. Br Heart J 38:773–778

Rissanen SM, Kankaanpää M, Meigal A et al (2008) Surface EMG and acceleration signals in Parkinson’s disease: feature extraction and cluster analysis. Med Biol Eng Comput 46(9):849–858

Rubulis A. (2007) T-vector and T-loop morphology analysis of ventricular repolarization in ischemic heart disease. Sundbyberg, larseric Digital Print AB

Rubulis A, Jensen J, Lundahl G et al (2004) T vector and loop characteristics in coronary artery disease and during acute ischemia. Heart Rhythm 1(3):317–325

Sanz E, Steger JP, Thie W (1983) Cardiogoniometry. Clin Cardiol 6:199–206

Schüpbach WM, Emese B, Loretan P et al (2008) Non-invasive diagnosis of coronary artery disease using cardiogoniometry performed at rest. Swiss Med Wkly 138(15–16):230–238

Seeck A, Huebner T, Schuepbach M, et al. (2007) Nichtinvasive Diagnostik der koronaren Herzerkrankung mittels Kardiogoniometrie. In: Proceedings 41st DGBMT annual meeting. biomed tech. 5 2CD ROM: 47439

Seeck A, Garde A, Schuepbach M (2009) Diagnosis of ischemic heart disease with cardiogoniometry—linear discriminant analysis versus support vector machines. In: Vander Sloten J, Verdonck P, Marc Nyssen M, Haueisen J et al (eds) IFMBE proceedings. Springer, Berlin

Villella A, Maggioni AP, Villella M et al (1995) Prognostic significance of maximal exercise testing after myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic agents: the GISSI-2 data-base. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza Nell’Infarto. Lancet 346:523–529

von Mengden HJ, Mayet W, Lippold K et al (1981) Pattern quantification of coronary artery stenosis by computerized analysis of multiple ECG parameters (author’s transl). Klin Wochenschr 59:629–637

Wilson FN, Johnston FD (1938) The Vectorcardiogram. Am Heart J 16:14–28

World Health Organization. The 10 leading causes of death by broad income group (2004), Fact sheet N°310, Geneva, Updated October 2008

Zareba W, Badilini F, Moss AJ (1994) Automatic detection of spatial and dynamic heterogeneity of repolarization. J Electrocardiol 27(Suppl):66–72

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huebner, T., Michael Schuepbach, W.M., Seeck, A. et al. Cardiogoniometric parameters for detection of coronary artery disease at rest as a function of stenosis localization and distribution. Med Biol Eng Comput 48, 435–446 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-010-0594-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-010-0594-1