Abstract

Background

Pharmacy benefit design is one tool for improving access and adherence to medications for the management of chronic disease.

Objective

We assessed the effects of pharmacy benefit design programs, including a change in pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), institution of a prescription out-of-pocket maximum, and a mandated switch to 90 days’ medication supply, on adherence to chronic disease medications over time.

Design

We used a difference-in-differences design to assess changes in adherence to chronic disease medications after the transition to new prescription policies.

Subjects

We utilized claims data from adults aged 18–64, on ≥ 1 medication for chronic disease, whose insurer instituted the prescription policies (intervention group) and a propensity score–matched comparison group from the same region.

Main Measures

The outcome of interest was adherence to chronic disease medications measured by proportion of days covered (PDC) using pharmacy claims.

Key Results

There were 13,798 individuals in each group after propensity score matching. Compared to the matched control group, adherence in the intervention group decreased in the first quarter of 2015 and then increased back to pre-intervention trends. Specifically, the change in adherence compared to the last quarter of 2014 in the intervention group versus controls was − 3.6 percentage points (pp) in 2015 Q1 (p < 0.001), 0.65 pp in Q2 (p = 0.024), 1.1 pp in Q3 (p < 0.001), and 1.4 pp in Q4 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In this cohort of commercially insured adults on medications for chronic disease, a change in PBM accompanied by a prescription out-of-pocket maximum and change to 90 days’ supply was associated with short-term disruptions in adherence followed by return to pre-intervention trends. A small improvement in adherence over the year of follow-up may not be clinically significant. These findings have important implications for employers, insurers, or health systems wishing to utilize pharmacy benefit design to improve management of chronic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases, including heart disease and diabetes, are among the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in the USA.1,2 Long-term adherence to medication is crucial for managing chronic disease.3,4,5,6 Pharmacy benefit design is one tool that can improve adherence to chronic medications by increasing affordability,7,8,9 convenience,10,11,12 and access.10,13,14

With the goal of improving management of chronic disease among its employees, a large-healthcare employer changed pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) and instituted two new pharmacy benefit programs for employees and their covered family members at the start of 2015. These included a prescription out-of-pocket maximum dollar amount graded based on employee income and a requirement that chronic medications be dispensed in 90 days’ supply. Reducing patient out-of-pocket costs has been shown to improve adherence through value-based insurance design,15,16,17,18 coupons,19 and low-cost medication options,20,21 among others.9 Providing medications in 90-day supplies22,23,24 and allowing for a mail-order option25 may also increase adherence through improved convenience.

However, with this switch, employees received a new pharmacy benefits card and had to provide that information to their pharmacy before filling prescriptions using insurance. Barriers, like prior authorization26 or drug formulary changes,27 are associated with a decrease in filling in some studies, at least in the short term. Less is known about the association between a change in PBM and adherence, especially without changes to the formulary, which may have important implications for access to medications and chronic disease management.

In this study, we assess the combined effect of the PBM change and new prescription policies on adherence to chronic medications over time.

METHODS

Overview

We used a difference-in-differences design with a cohort of Mass General Brigham (MGB)–insured individuals and a propensity score–matched comparison group to assess the association of prescription policy and PBM changes with adherence to chronic medications over time. Analytic work was performed by IBM Watson Health. This study was approved by the MGB Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

MGB, previously known as Partners Healthcare, is a large, non-profit health system in greater Boston that offers a fully self-funded insurance plan to employees and their families. Of approximately 56,000 MGB employees, about 46,000 employees and 55,000 of their family members were covered under MGB insurance plans in 2015. Medical and pharmacy claims for the intervention group were drawn from the MGB data warehouse and for the comparison group from the IBM MarketScan Research Database, which consists of > 250 million individuals with employer-sponsored health insurance nationwide.

We first found MGB plan members aged 18–64 who filled ≥ 2 prescriptions for ≥ 1 chronic medication (Appendix Table 1) between October 1, 2013, and December 31, 2014. The first eligible prescription fill in that window was considered the member’s “cohort entry” date. To ensure full capture of claims and covariates, individuals were required to be continuously enrolled from 6 months before cohort entry through the end of the outcome assessment period (December 31, 2015). Over 98% of the MGB plan members lived in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, or Rhode Island, so we restricted to those states. Individuals in the MarketScan database who were not insured by MGB were found using the same clinical, enrollment, and geographic criteria (Appendix Table 2).

Exposure

MGB made three changes to pharmacy benefits on January 1, 2015: (1) changed PBM; (2) instituted an income-based, prescription out-of-pocket maximum; and (3) mandated a switch to 90 days’ supply for most chronic medications (“maintenance choice”). The formulary and copay amounts did not otherwise change.

MGB insurance beneficiaries were mailed new member cards and information on the pharmacy benefit changes in November–December 2014. Pharmacies required the new benefit information to fill a prescription through insurance. Members could call a pharmacy in advance with the information or present the card at medication pickup. Some pharmacies could also look up coverage in databases, and others could call the plan help desk. There were changes to pharmacy in-network designations; however, most local pharmacies remained in-network.

The out-of-pocket maximum applied specifically to prescription costs and required no additional action by the member. The maximum was based on the employee’s annual income, with individual and family plan maximums set at $250/$500 USD for an annual salary < $50,000; $800/$1600 for salaries $50,000–$100,000; and $1600/$4000 for salaries > $100,000 (Appendix Table 3). When an employee or family reached the out-of-pocket maximum, all medications had a $0 copay for the remainder of the calendar year. For example, an employee with an individual plan making < $50,000/year filling medications with a total monthly copay of $100 would have paid $100 in January, $100 in February, and $50 in March, met her $250 maximum in March, and subsequent copays would be $0, including any new medications. This would then reset at the beginning of the next calendar year.

Maintenance Choice required a 90-day supply for most chronic medications and in some cases required action by the member. Maintenance medications were defined by MGB and the PBM and included medications for diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, thyroid disorders, kidney disease, depression, and respiratory diseases. Members could choose to fill 90 days’ supply of qualifying medications at an in-network pharmacy or receive the medications by mail. Maintenance Choice also reduced out-of-pocket costs of these medications; members paid the copayment for 60 days of medication but received 90 days’ supply. While transitioning to Maintenance Choice, employees could fill up to three, 30-day scripts, then a transition to 90 days’ supply was required for all qualifying medications. Some pharmacies automatically contacted prescribers to request 90-day supplies, but in some cases, members had to request new prescriptions directly.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is adherence to chronic medications assessed by proportion of days covered (PDC) using pharmacy claims data. To measure adherence, we first identified chronic medications that patients filled twice between October 1, 2013, and December 31, 2015. We then generated a supply diary for each medication by aggregating consecutive fills based on dispensing date and days supplied. Medications within the same molecularly related class were considered interchangeable (e.g., beta-blockers). As in prior work,28 once a class met criteria, it was incorporated into the calculation for the study, including new medication initiations in the follow-up period. We then calculated the proportion of days covered (PDC) for each individual, across all qualifying chronic medications, for each calendar month. Finally, we averaged monthly PDCs among MGB beneficiaries and matched controls to obtain monthly adherence means by study group.

Covariate Assessment

Baseline covariates were identified using prior literature and clinical knowledge and were assessed in the 6 months before cohort entry (Appendix Figure 1). Covariates included age, gender, relationship (employee, spouse, dependent), and plan type. We used US Census data to obtain zip-code-level information about mean household income, percent white race/ethnicity, and percent that had not completed high school. Comorbidities were defined using ICD-9 codes, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Deyo adaptation)29 was calculated. Baseline out-of-pocket medical and prescription costs, number of unique medications, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and outpatient office visits were calculated. The number of days between cohort entry and January 1, 2015 (policy switch date) was counted as a measure of time prior to exposure start.

Propensity Score Matching

A propensity score was generated using multivariable logistic regression with participant age, gender, relationship, Charlson Comorbidity Index, plan type, state, zip-code-linked sociodemographic characteristics, types of chronic medications, number of days prior to January 1, 2015, and baseline out-of-pocket medical costs, out-of-pocket prescription costs, hospitalizations, ED visits, outpatient visits, and unique prescriptions as covariates. The specific variable classifications are in Appendix Table 4. Because geography was deemed an important potential confounder, participants were first exact matched by metropolitan statistical area and then 1:1 propensity score–matched using a greedy matching algorithm and caliper width = 0.05.

Statistical Analysis

We used a difference-in-differences approach to compare adherence to chronic medications from the fourth quarter of 2014 (baseline) to each quarter of 2015 in the MGB group compared to the matched control group. Monthly medication adherence rates for MGB plan members and matched controls were plotted. Tests for normality showed the normal distribution adequately fit the data. Because we hypothesized that the effects of the interventions might vary over time, the 2015 calendar year was divided into quarters for outcome analysis. We did not detect violation of parallel trends between groups in the pre-intervention period (joint test of coefficients p > 0.10). For the main outcome, regression was performed using an identity link and gaussian distribution, adjusting for standard errors for repeated measures by person. Interaction terms between the intervention group and each quarter of 2015 were used to assess for changes in adherence between MGB plan members and the matched comparison group between baseline and each quarter of 2015. Analyses were conducted with and without adjustment for covariates. WPS Workbench version 4.1 Software with SAS input language was used for analyses.

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

Because including new medication starts in during follow-up could affect the results if rates differed between the groups, we performed a sensitivity analysis of the main outcome including only medications filled before the policy switch date. We performed an additional sensitivity analysis utilizing all of 2014 as the baseline comparison period.

We performed exploratory descriptive analyses to investigate how adherence changed among those who met the maximum out-of-pocket. First, plan members who met the maximum out-of-pocket were found by selecting individuals whose eligible copays transitioned from > $0 to $0 anytime in 2015. The month in which the first $0 copay occurred was considered the month that the member, and family if applicable, met the out-of-pocket maximum. To avoid bias that would result from matching based on an event that occurs in the outcome measurement period, only exploratory descriptive analyses are presented using the original propensity score–matched controls. We plotted monthly adherence rates and medical and pharmacy costs before and after meeting the maximum out-of-pocket.

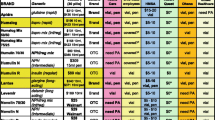

RESULTS

Overall, 16,662 MGB employees and covered family members met the criteria for cohort entry, and 83% were propensity score–matched, which resulted in 13,798 in each group (Appendix Table 2). Demographic and clinical characteristics before and after matching are shown in Table 1. Among MGB plan members in the final cohort, average age was 48 years, 61.1% were employees, and on average they resided in areas that were 77.4% white and had a median household income of $87,717. The most common medication group was cardiac (51.2%), followed by lipid lowering (38%) and depression/anxiety (36%). Baseline characteristics were similar in the matched comparison group; absolute standardized differences were < 0.1 for all matched covariates (post-match C-statistic = 0.554).30

Overall adherence trends for MGB members and the comparison group are displayed in Figure 1. On average, adherence was 3 percentage points (pp) lower among MGB members compared to matched controls from 2013 Q4 through 2014 Q4 and 4 pp lower in the baseline comparison period of 2014 Q4 (Table 2). In the main analysis, change in adherence compared to 2014 Q4 in the MGB group versus controls was − 3.6 pp in 2015 Q1 (p < 0.001), 0.65 pp in Q2 (p = 0.024), 1.1 pp in Q3 (p < 0.001), and 1.4 pp in Q4 (p < 0.001) (Table 3). These results were similar after adjustment for covariates and in sensitivity analyses (Appendix Table 4). The percentage of prescriptions dispensed in 90 days’ supply in the baseline period was 11.7% in the MGB group and 24.9% in the comparison group and increased to 23.3% in the MGB group and 26.6% in the comparison group after the policy change.

Of the propensity score–matched sample, 1037 MGB plan members met the maximum out-of-pocket in 2015. The characteristics of these individuals and their matched controls are presented in Appendix Table 5. MGB plan members reached the out-of-pocket maximum as early as January 2015 and as late as December 2015. The mean month for meeting the maximum was July 2015 (SD 2.6 months). Plots of adherence among MGB plan members who met the maximum out-of-pocket and their matched controls are presented in Appendix Figure 2 and Table 2. Baseline adherence was similar between the groups. In the follow-up period, adherence decreased to 63% in 2015 Q1 and then gradually increased to 67% in Q4 among MGB plan members, while adherence gradually declined to 62% by Q4 in their matched controls. Adherence over time among patients who did not meet the maximum out-of-pocket and their matched controls was similar to the overall results (baseline characteristics in Appendix Table 5 and adherence plots in Appendix Figure 3).

Monthly out-of-pocket prescription costs among MGB plan members who met the maximum out-of-pocket decreased after they met the maximum ($44.96 [SD $38.85] before and $0.84 [SD $4.32] after), and monthly mean prescription payments made by the payor increased from $524.37/month (SD $1449.53) before to $635.13/month (SD $1735.14) after. This group also filled slightly more unique prescriptions per month after meeting the maximum (3.5 [SD 2.39] before vs 3.7 [SD 2.66] after). Total monthly medical spending was similar before ($1117.00 [SD $2618.60]) and after ($1145.20 [SD $3544.27]) meeting the maximum.

DISCUSSION

In this study of commercially insured adults on medications for chronic disease, the combination of a change in PBM, a prescription maximum out-of-pocket, and mandatory 90 days’ supply was associated with an initial decrease in adherence followed by a return to pre-intervention baseline trends. Over time, the interventions may have improved adherence, though effects appear to be more pronounced among those who met the maximum out-of-pocket, and the small increases in adherence relative to controls seen in the full sample may not be clinically significant. Taken together, these findings suggest that the prescription policy changes likely resulted in short-term, but not long-term, disruptions in adherence.

The overall impact of the policies is similar in magnitude to other adherence interventions.31 Though absolute changes are often small, when applied at scale, small changes can result in meaningful differences in morbidity.32 For example, a 5 percentage point (pp) increase in adherence to cardiac medications after myocardial infarction was enough to decrease total major vascular events or revascularization by 11%.33

Because the three interventions occurred simultaneously, we are unable to definitively separate the effects of each individual change. However, we can speculate on their relative contribution based on the expected timing of the effects of each intervention.

First, the change in PBM required plan member action prior to filling in 2015, and action was also sometimes required for transition to 90 days’ supply. This could have interfered with on-time prescription filling and might in part explain the decrease in adherence observed early in 2015 for MGB-insured individuals. To overcome this, some individuals could have paid cash for prescriptions early in 2015 if they had difficulty producing the new insurance information at the pharmacy. Because this would not generate a claim observable in this dataset, paying cash could have made adherence appear to decrease when plan members were actually continuing their medications. Lastly, if MGB members discontinued or changed medication classes more during 2015 Q1, this could also cause an apparent decrease without reflecting true non-adherence. However, because there were no other changes to formulary or costs, this would be likely non-differential. It is therefore probable that barriers related to the PBM change account for the observed decrease in adherence in 2015 Q1. While the impact of PBM changes has not been previously quantified, similar barriers like drug formulary changes are associated with a short-term decrease in filling in some studies.27 Even short-term or partial non-adherence has been associated with worsened cardiovascular outcomes.34 Therefore, to help prevent a decrease in adherence around a transition in benefits, employers could try to automate the process where possible and minimize barriers to obtaining medications with the new plan.

Second, the maximum out-of-pocket and maintenance choice changes may have contributed to the subsequent return to pre-intervention trends and small increase in MGB members’ adherence through the remainder of 2015 compared to matched controls. Approximately 10% of plan members who met the maximum out-of-pocket improved their adherence by about 5 pp compared to controls, which would be consistent with prior research on health spending after patients reach a deductible.35 Additionally, though the process of switching to 90-day supplies may have contributed to an initial decrease in adherence, over time, we might expect the improved convenience to increase adherence, and this could have had an effect for all MGB plan members. However, increases in adherence among the full MGB cohort were modest and may not be clinically significant.

This study has some important limitations. First, there is a small (3–4 pp) difference in baseline adherence between the two groups, which could be due to some unmeasured variation. However, baseline trends are similar, and the difference-in-differences design accommodates this small separation. Second, dispensing medications in 90 days’ supply delays our ability to observe non-adherence using gaps between fills and thus may slightly artificially inflate calculations. When using claims to measure adherence, it may not be possible to disentangle differences between true changes in adherence and improved convenience of 90-day supplies. However, any inflation would occur soon after the switch and thus for the intervention group would likely occur in 2015 Q1 or Q2, and we address this limitation by continuing follow-up through all of 2015. Third, this study is limited to one large health employer and may not be fully generalizable. Fourth, similar to studies that use the same approach,28 overall adherence appears low and decreases over time. This downward trend is because with claims, we cannot differentiate provider-directed discontinuation from patient non-adherence, and so once a medication is initiated, it is included in the adherence calculation throughout follow-up. To overcome this, we used a difference-in-differences design, calculated adherence the same way in both groups, and counted switching within a medication class as ongoing adherence, which ensured that relative changes are still precise. Lastly, we cannot determine the individual contribution of each policy change; prospective research may be needed to more precisely understand the effects of each intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

The combination of a change in PBM, institution of a maximum out-of-pocket for prescription medications, and mandatory 90-day supplies of chronic disease medications was associated with an initial decrease in adherence followed by a return to pre-intervention trends. These findings have important implications for healthcare plans and providers when considering appropriate policy levers to improve the management of chronic diseases.

References

National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 68, Number 9 June 24, 2019 Deaths: final data for 2017. :77.

Benjamin Emelia J., Virani Salim S., Callaway Clifton W., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558

Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43(6):521-530. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af

Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Garrido E, et al. Assessing the impact of medication adherence on long-term cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(8):789-801. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.005

Neiman AB. CDC Grand Rounds: improving medication adherence for chronic disease management — innovations and opportunities. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6645a2

Walsh CA, Cahir C, Tecklenborg S, Byrne C, Culbertson MA, Bennett KE. The association between medication non-adherence and adverse health outcomes in ageing populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(11):2464-2478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14075

Milan R, Vasiliadis H-M, Gontijo Guerra S, Berbiche D. Out-of-pocket costs and adherence to antihypertensive agents among older adults covered by the public drug insurance plan in Quebec. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1513-1522. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S138364

Karter AJ, Parker MM, Solomon MD, et al. Effect of out-of-pocket cost on medication initiation, adherence, and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1227-1247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12700

Mann BS, Barnieh L, Tang K, et al. Association between drug insurance cost sharing strategies and outcomes in patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089168

Liberman JN, Girdish C. Recent trends in the dispensing of 90-day-supply prescriptions at retail pharmacies: implications for improved convenience and access. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2011;4(2):95-100.

Karter AJ, Parker MM, Duru OK, et al. Impact of a Pharmacy Benefit Change on New Use of Mail Order Pharmacy among Diabetes Patients: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):537-559. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12223

Liberman JN, Wang Y, Hutchins DS, Slezak J, Shrank WH. Revealed preference for community and mail service pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2011;51(1):50-57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2011.09161

Birdsall AD, Kappenman AM, Covey BT, Rim MH. Implementation and impact assessment of integrated electronic prior authorization in an academic health system. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(4):e93-e99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2020.01.012

West JC, Wilk JE, Rae DS, et al. Medicaid prescription drug policies and medication access and continuity: findings from ten states. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(5):601-610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.601

Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Avorn J, et al. At Pitney Bowes, value-based insurance design cut copayments and increased drug adherence. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2010;29(11):1995-2001. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0336

Farley JF, Wansink D, Lindquist JH, Parker JC, Maciejewski ML. Medication adherence changes following value-based insurance design. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(5):265-274.

Gibson TB, Wang S, Kelly E, et al. A value-based insurance design program at a large company boosted medication adherence for employees with chronic illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(1):109-117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0510

Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Smith BF, et al. Five features of value-based insurance design plans were associated with higher rates of medication adherence. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(3):493-501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0060

Starner CI, Alexander GC, Bowen K, Qiu Y, Wickersham PJ, Gleason PP. Specialty drug coupons lower out-of-pocket costs and may improve adherence at the risk of increasing premiums. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(10):1761-1769. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0497

Choudhry NK, Shrank WH. Four-dollar generics — increased accessibility, impaired quality assurance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1885-1887. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1006189

Zhang Y, Gellad WF, Zhou L, Lin Y-J, Lave JR. Access to and use of $4 generic programs in Medicare. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1251-1257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-1993-9

Batal HA, Krantz MJ, Dale RA, Mehler PS, Steiner JF. Impact of prescription size on statin adherence and cholesterol levels. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-175

King S, Miani C, Exley J, Larkin J, Kirtley A, Payne RA. Impact of issuing longer- versus shorter-duration prescriptions: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2018;68(669):e286-e292. doi:https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X695501

Miani C, Martin A, Exley J, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of issuing longer versus shorter duration (3-month vs. 28-day) prescriptions in patients with chronic conditions: systematic review and economic modelling. Health Technol Assess Winch Engl. 2017;21(78):1-128. doi:https://doi.org/10.3310/hta21780

Fernandez EV, McDaniel JA, Carroll NV. Examination of the link between medication adherence and use of mail-order pharmacies in chronic disease states. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(11):1247-1259. doi:https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.11.1247

Happe LE, Clark D, Holliday E, Young T. A systematic literature review assessing the directional impact of managed care formulary restrictions on medication adherence, clinical outcomes, economic outcomes, and health care resource utilization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(1):677-684. doi:https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.7.677

Shirneshan E, Kyrychenko P, Matlin OS, Avila JP, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. Impact of a transition to more restrictive drug formulary on therapy discontinuation and medication adherence. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(1):64-69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12349

Lewey Jennifer, Gagne Joshua J., Franklin Jessica, Lauffenburger Julie C., Brill Gregory, Choudhry Niteesh K. Impact of high deductible health plans on cardiovascular medication adherence and health disparities. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(11):e004632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004632

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8

Franklin JM, Rassen JA, Ackermann D, Bartels DB, Schneeweiss S. Metrics for covariate balance in cohort studies of causal effects. Stat Med. 2014;33(10):1685-1699. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6058

Conn VS, Ruppar TM. Medication adherence outcomes of 771 intervention trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2017;99:269-276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.008

Toy EL, Beaulieu NU, McHale JM, et al. Treatment of COPD: Relationships between daily dosing frequency, adherence, resource use, and costs. Respir Med. 2011;105(3):435-441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.006

Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, et al. Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2088-2097. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1107913

Bitton A, Choudhry NK, Matlin OS, Swanton K, Shrank WH. The impact of medication adherence on coronary artery disease costs and outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):357.e7-357.e27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.09.004

Brot-Goldberg ZC, Chandra A, Handel BR, Kolstad JT. What does a deductible do? The impact of cost-sharing on health care prices, quantities, and spending dynamics. Q J Econ. 2017;132(3):1261-1318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx013

Funding

This work was supported by institutional funds at Mass General Brigham. Dr. Haff reports salary support from Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Gibson and Ms. Benevent report support from Brigham and Women’s Hospital / Mass General Brigham during the conduct of the study. Dr. Chaguturu reports personal fees from Mass General Brigham and personal fees from CVS Caremark outside of the submitted work. Dr. Lauffenburger was supported by a career development award K01HL141538 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 3124 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haff, N., Sequist, T.D., Gibson, T.B. et al. Association Between Cost-Saving Prescription Policy Changes and Adherence to Chronic Disease Medications: an Observational Study. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 531–538 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07031-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07031-w